Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.73 Bogotá Jan./June 2011

The Country and the City in the Cuban Revolution

Michelle Chase*

* Michelle Chase es catedrática postdoctoral del Centro de Estudios de América Latina y el Caribe de la Universidad de Nueva York, Nueva York, Estados Unidos. michelle.chase@nyu.edu.

Abstract

This article examines the interplay between city and country in the earliest years of the Cuban Revolution of 1959. It argues that the mass movement of Cubans, especially youths, between urban and rural areas was a major factor in contributing to the radical conscious-ness of the 1960s. At the same time, these early initiatives also contributed to the growing disaffection with the Cuban revolution. The article, thus, lends insight into the excitement and polarization of Cuba's "revolutionary moment."

Keywords

Cuba • revolution • socialism • cities • 1960 • the Left

El campo y la ciudad en la Revolución Cubana

Resumen

El artículo examina la interacción entre ciudad y campo en los primero años de la Revolución Cubana de 1959. Se sostiene que el movimiento masivo de cubanos, especialmente jóvenes, entre las ciudades y las zonas rurales fue un factor importante para contribuir a la toma de conciencia radical de los años sesenta. Estas iniciativas tempranas también contribuyeron al crecimiento de la insatisfacción con la Revolución Cubana. El artículo ofrece revelaciones acerca de la emoción y la polarización del "movimiento revolucionario" de Cuba.

Palabras clave

Cuba • revolución • socialismo • ciudades • 1960 • izquierda

Recibido el 17 de diciembre de 2010 y aceptado el 14 de abril de 2011.

Recent waves of historiography on Latin American social revolutions in the twentieth-century have tended to concentrate on peasant participation and the rural context. Such a focus is highly justifiable for a region that was, until recently, predominantly rural, had economies based on export agriculture, and in which a major axis of political and social tension was the issue of highly inequitable land distribution. This focus also reflects a political and scholarly commitment to subaltern politics, initially forged in the 196üs, when two seminal studies laid the groundwork for conceptualizing "Third World" revolutions. John Womack's now-classic study Zapata and the Mexican Revolution introduced an enduring vision of the peasant as revolutionary leader and established the centrality of agrarian politics to the Mexican revolution. Similarly, Eric Wolf's comparative study Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century, written during the height of American involvement in Vietnam, inaugurated a long-standing focus on the peasantry as the crucial subject of the decolonization and national liberation struggles that marked the post-war world. This scholarly focus on the peasantry has resulted in many excellent studies that have laid important foundations for our under-standings of rural participation in revolution.1

Nevertheless, historians should not overlook the urban context when studying revolutionary processes in Latin America. We know less than we should about the participation of urban social classes, the transformations to urban institutions and the constructed environment, as well as the chang-es to the symbolism of city and country during revolutions.2 The present article will focus on the Cuban revolution during its foundational period of 1959 to 1962 to analyze just how our understanding of the revolution may be enriched by viewing it through this lens.3

The article will argue that many of the earliest revolutionary initiatives were animated by a desire to reduce the distance between city and country and to level out the naturalized, historically produced hierarchies between them. These early initiatives often produced, both by accident and by design, mass movements between city and countryside, especially of young people. Both explicitly and implicitly, many of the earliest transformations of the revolution also raised a series of questions about city and country, such as who had a right to the city, and what rights accrued to the city and its inhabitants. This article will suggest that those early, zealous attempts to bridge the urban-rural divide help explain some of the passionate appeal of the "revolutionary moment." The fundamental appeal of this revolutionary vision of new relations between the country and the city lay in its rejection of older models of Catholic charity or liberal uplift, embracing a more radical notion of rural empowerment. Yet at the same time, the sense of disorien-tation that these changes sparked in some Cubans became a central factor in their opposition towards and criticism of the revolution. Thus a focus on the question of country and city can help illuminate the rapid political radicalization and polarization that took place in the first few years of the revolution, a process that is still poorly understood.

In the following text, I will discuss first the appeal that the country-side-especially the Sierra Maestra region-had on the revolutionary imagi-nation. This manifested itself in early revolutionary programs designed to replicate the guerrilla experience of the commune with the peasantry for urban youth that were too young to have participated in the insurrection against Fulgencio Batista. These programs included pilgrimages to the Sierra Maestra led by the new mass organizations, various educational initiatives, and agricultural pilot programs. The article will then examine the various transformations to the city engendered by initiatives that brought rural youths to the city, by various forms of political conflict, and by transformations to both production and commerce. The intention of the article is not to assess the effectiveness of such changes, nor to judge their eventual outcomes. Rather, my aim here is to argue that these transformations to the real and imagined roles of city and country are crucial to understanding the consciousness of the revolutionary generation-including both those who embraced the revolution and those that opposed it-and, thereby, to illumi-nate the political dynamics of the "revolutionary moment.

CITY AND COUNTRY IN REPUBLICAN CUBA

Havana in the i95os was a city of contrasts: It was a cosmopolitan, modern city marked by cutting-edge architecture, US-style suburbs, and growing international tourism. And yet it was also the capital of a declining sugar island, in which the shrinking agricultural sector was offset only by a slowly growing urban service sector. Founded in 1519 around a sheltered harbor, it had primarily been a point of transit for trans-Atlantic shipments during the early colonial period, and was the capital city of a largely undeveloped colonial territory. When the island's sugar boom began in the late eighteenth century, Havana became a more prosperous, prominent commercial city. Many of the major avenues were laid in the nineteenth century, when Cuba's importance as a global sugar producer swelled.4 The city underwent a popula-tion explosion during the first half of the twentieth century due to the sugar boom of the early 1920s and the consequent surge in construction, as well as the rise of some light manufacture and the growth of services, all of which drew population to the capital (Scarpaci, Segre and Coyula 2002, 119-120).

Like other Latin American cities, Havana was characterized by a colonial core that encompassed government offices and commerce, and a growing ring of improvised housing on the city outskirts for the urban poor. Cuba's favored trading partner status with the United States made it wealthier and more developed than many other Caribbean cities, and this new wealth was visible in the new developments reminiscent of American suburbs that extended to the west and south of the harbor, where the city's middle and upper classes resided. Although the oldest barrios of Havana retained the daily rhythms more typical of a pre-modern city, marked by a certain "medieval ideal of vecinería" (Álvarez-Tabío Alba 2000, 230) well into the twentieth century, by the i950s, Havana was considered one of most mod-ern cities of the Caribbean. Skyscrapers rose in the city's new commercial center, cars imported in the post-war period now clogged streets with traf-fic, American department stores and supermarket chains began to dot the landscape, and US-made products flooded stores (Álvarez-Tabío Alba 2000, 235-236). The geographical proximity and historical influence of the United States gave Cuban cities an emphasis on mass culture and consumerism that was probably unparalleled in the region. The future of the city was clear: "Floridization."5 The future of the island also seemed determined: continued urban growth, either through industrialization or, more likely, through the continued growth of the service sector.

The Cuban countryside had witnessed "Americanization" of another kind, namely the rise of a predominantly foreign-owned sugar sector comprised of enormous plantations, especially in the eastern part of the island. After Cuba's damaging final war for independence (1895-1898) left much of the country's sugar sector destroyed, the American occupation of 1898 to 1902 streamlined property laws, rationalizing old Spanish colonial partitions and abolishing collective forms of tenure. The combination of "virgin," highly fertile sugar lands and the US protection of property rights facilitated enor-mous US investment in these new sugar plantations that rose in the early decades of the twentieth century, especially in the east of the island, where destruction had been particularly severe and the sugar sector's infrastruc-ture had been most antiquated.

By the 1930s, the foreign-dominated agricultural sector had become a major point of contention in Republican politics. The 1933 revolution and its complex aftermath eventually enshrined the concept of limiting the size of large sugar estates in the 1940 constitution. Although the details of such limitation were never spelled out nor properly implemented, the ideal of land reform remained an important milestone and symbolic goal. Indeed, agrarian reform was a central demand from the center to the left of the Cuban post-war political establishment. Conscious of belonging to a relatively modern, cosmopolitan city, many progressive habaneros viewed the Cuban countryside as in urgent need of reform. Throughout the decade of the i950s, it was common political currency to demand agrarian reform and to bemoan the impoverished state of the countryside as blight on Cuban modernity. Progressive publications such as Bohemia magazine were filled with features about the poverty and unequal land distribution of the countryside. Films such as Los carboneros, borrowing from Italian neo-realism, dramatized the dismal conditions and labor exploitation of charcoal workers in the Cienaga de Zapata region. Catholic student groups documented the hardships of rural life through surveys and studies, and rallied their members to undertake collections for local economic aid ef-forts (Fernández Soneira 2002). Despite certain elements of nationalistic pride in the Cuban campo and idyllic representations of the countryside in the arts in the i930s and i940s, the countryside was most often seen as a place in need of moral as well as economic reform, a place to be improved rather than emulated.

FROM CITY TO COUNTRY

The 1959 triumph of insurrectionary forces brought new ideas about the countryside to the fore, due both to the explosion of popular optimism about equitable development that characterized post-war Latin America, as well as a more particular idea about the countryside that had developed within the rebel army. When rebel forces led by Fidel Castro launched an armed expedition from Mexico, they landed in the desperately poor coffee zones of the Sierra Maestra. They were struck by the misery they found there. The ensuing process of slowly building a guerrilla army in the Sierra, gradually attracting the cooperation and loyalty of local peasants, has become part of the revolution's official narrative. For the young men of the city who formed the initial cadres of the rebel army, the experience contributed to their political radicalization, giving them a more urgent sense of the need for agrarian reform. As Che Guevara noted, "We began to feel in our bones the need for a definitive change in the lives of these people. The idea of agrarian reform became clear, and communion with the people ceased being theory and became a fundamental part of our being." (Che Guevara 2006 [1963], 83) Fidel Castro's experience in the Sierra also convinced him that Havana was too large for a country like Cuba. He subsequently described it as "an over-developed capital in a completely underdeveloped country," and this view contributed to his intentional long-term policy of committing more state resources to the development of the countryside, purposefully neglecting the city (Lockwood 1969, 104).

Additionally, members of the rebel army drawn from the cities experi-enced a quasi-spiritual sense of brotherhood and masculine camaraderie, almost a Christian state of "communitas," as they struggled to survive initial hardships and eventually fought Batista's army side by side with the local peasants who joined the guerrilla army (Guerra 2009, 81). These were the experiences that led the rebel leadership to promulgate an idea of the campo as the site of material impoverishment and injustice, but yet also of spiritual and political strength. They viewed the Sierra Maestra, and by extension the Cuban countryside in general, as a site with transformative power. Some of the earliest revolutionary initiatives were thus animated by a desire to replicate the guerrilla experience of political radicalization, heightened consciousness, and urban-rural bonding.

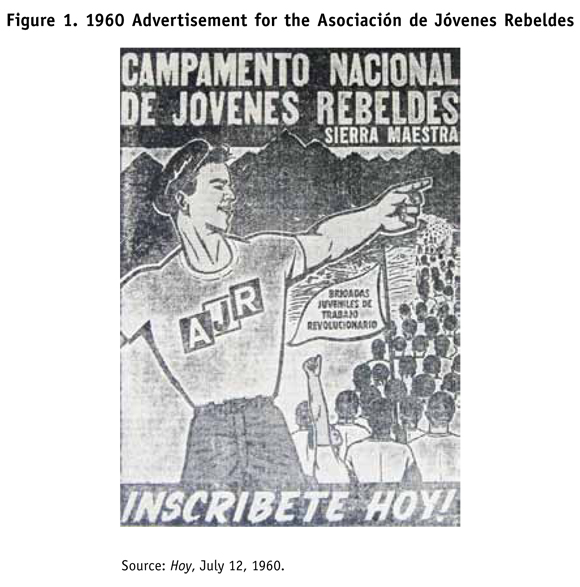

After the revolutionary triumph of 1959, the powerful mystique of the Sierra led thousands of urban Cuban youths to participate in various pro-grams that brought them to the countryside, for short or long periods. With the formation of mass organizations that targeted young people in particular, many youths eagerly took part in quasi-military endurance hikes to emulate the scaling of the highest peak of the Sierra, Pico Turquino. For example, the Asociación de Jóvenes Rebeldes (later to become the Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas) led a series of hikes to the Sierra, through which urban revolutionaries hoped to replicate the determination and exertions of the rebel army. An AJR ad pictured in the following page (figure 1) shows a strap-ping young man with a beret point to the crest of the mountains, while other association members march up the mountain in disciplined formation.6

If trips to the Sierra led by the mass organizations were often of short duration, the various educational initiatives that began immediately after the revolutionary triumph eventually had the effect of bringing many urban youths to the countryside for months at a time. Literacy and education in general were central to the rebel vision of rural empowerment, and in fact makeshift schools for peasants had been already set up by rebels in the "lib-erated territories" by 1958. The first classes apparently included both peasants who had joined the rebels in their struggle and other illiterate locals.7 With the revolutionary victory of January 1959, other educational initiatives for the rural areas-especially for Oriente province, where the Sierra Maestra mountain range was actually located-were quickly developed by various individual volunteers, many of whom were professional teachers; committees organized by rebel groups, and Catholic groups. The twin prom-ises of agrarian reform and education were seen as central in ending the isolation and poverty of the countryside, and some young urban activists at-tempted to join the embryonic rural educational initiatives in 1959 and 1960 as a continuation of their earlier revolutionary militancy (with the 26 of July Movement or some other group) and as a way to replicate the transformative experience that the rural-based guerrilla had enjoyed in the Sierra.8

The project of bringing knowledge to the countryside was deeply political on many levels. For many former militants, urban and rural, the campaign was viewed with a revolutionary zeal born of the fabled encounter of rural and urban combatants in the Sierra, and seen partly within a framework of repaying the peasant sacrifice to the insurrection. Some also saw rural illiteracy within a larger narrative of capitalist exploitation and underdevel-opment; in other words, illiteracy and ignorance were seen as the necessary counterpart to labor exploitation. The campaign was also viewed by the leadership as helping to construct future revolutionary subjects both in the countryside and among the young urban cadres who were the campaign's foot soldiers.9

Thus, one of the first social development projects in the Sierra Maestra was a massive "city school," the Ciudad Escolar Camilo Cienfuegos, constructed on the site of a pre-revolutionary military barracks. The stated purpose of the school was to provide education in the underserved, sparsely-developed mountainous areas of the Sierra. The Ciudad Escolar, as Fidel Castro de-scribed it, was to serve as a kind of magnet school, drawing the best students from the region, "los mejores muchachos de cada escuelita rural." He hoped to eventually have as many as twenty thousand students living and studying there, presumably all male, drawn from the new rural schools the revolution promised to establish.10

The imagery surrounding the school was openly martial, suggesting the school was an extension of the revolutionary struggle of the Sierra. In fact, some of the first volunteers in establishing the school were the all-women's brigade which had fought in Fidel Castro's column, the Mariana Grajales brigade. Following the revolution's triumph, the brigade had remained in the Sierra, carrying out preliminary survey work to determine the educa-tional needs of the area, and subsequently they stayed on to help construct the school itself (Cardosa Arias 1960). International brigades of volunteer workers also worked on the construction of the school, and delegations of international visitors came to witness the unprecedented revolutionary initiative.11 The school not only promised to bring education to neglected areas; it was also conceived of as an "encuentro" between country and city, within a militarized model of rural redemption.

For example, an ad for the Ciudad Escolar Camilo Cienfuegos placed by the Ministry of Education shows two young boys wearing berets, looking off into the distance. The text, written in verse form, compares the conflict of the struggle against Batista with the new battle for knowledge and urban-rural harmony:

- Otra fragua en la Sierra

Ayer fue la promesa

heroica cumplida

en sangre rebelde.

Hoy es la luz de la Escuela

iluminando el séptimo

26 de julio

con el encuentro de la

ciudad y la montaña.

Pequeñas manos

campesinas

que se llenan de libros.

Ojos que enfrentan

el futuro seguros de

vencerlo...

Porque sobre esas

cumbres se forjan los

héroes de mañana.12

The Ciudad Escolar served as a focal point for interactions between urban volunteers and the rural populace. In the euphoria of the revolutionary mo-ment, many urban youths signed up to work as volunteer teachers in the Sierra, including many young women. By 1960 the Sierra was awash with voluntary teachers, perhaps as many as 1/700.13 It was a way of participating in the revolution and experiencing what the guerrilla army had experienced. For example, one young woman working as a teacher at a public school in Havana requested a transfer to the new school and worked there for five months, despite her misgivings about the political direction of the revolu-tion. "They said [the revolution] would protect the campesinos. I asked for a transfer to the campo, to the Sierra Maestra, where a mega-school was being built. Everything was under construction; there were no comforts of any kind. For a time I felt good, because I was able to help those children. 14

Soon, the drive to bring education to the most remote corners of the island expanded into the enormous island-wide literacy campaign of 1961. In many ways, the campaign was the culmination of the revolutionary transformation of education, which now became definitively associated with national liberation, the end of capitalist exploitation, and subaltern empowerment. The plan, as announced by Fidel Castro in the fall of 1960, was highly ambitious but it was also highly disruptive: all schools would be closed for more than eight months while urban children as young as 13 departed for the countryside to live and work with campesino families while they taught their hosts to read. The scale of the mobilization was massive: eventually more than a million Cubans took part, either as students or teach-ers. The campaign successfully utilized the newly-formed mass organizations and the newly-consolidated, government-controlled publicity machine, and functioned as a kind of pilot program for later mass mobilizations. The 1961literacy campaign mobilized more Cubans than any other single revolution-ary program and had an enormous social and political impact.15

Usually discussed in the context of formal education, the 1961 Literacy Campaign also had a strong subtext of exposing young urban Cubans to the hardships and inspirations of the countryside, and transforming them politically through the experience. In speeches, Fidel Castro explicitly noted the political impact he hoped the campaign would have on the young urban brigadistas who participated:

- [The peasants] will show you what rural life in Cuba was: without roads, parks, electric lights, theaters, movies. ... They will teach you how living creatures had to suffer under exploi-tation from selfish interests. They will teach you what it is to have lived without sufficient food; they will teach you what it is to live without doctors and hospitals. They will teach you, at the same time, what is a healthy, sound, clean life; what is upright morality, duty, generosity, sharing the little they have with visitors.16

The quote reflects the leadership's assumption that country life was purer than life in the cities, which they viewed as tinged by consumerism and superficiality. The exposure to rural hardships would, they hoped, be a character-forming process for urban youths just as it had for the rebel army. The experience apparently did prove to be life-changing for many urban youths.17 It was, for many, the first time they came into significant contact with different social strata and the first time they lived away from their families. It reproduced at some level the deep impact rural poverty had made on many urban revolutionaries in the Sierra, just as the revolutionary leadership intended. The impact was not restricted to children of the urban middle class; conditions in the most remote regions of Oriente Province were so difficult that the contrast in living standards with even the urban working class was abysmal. As one former brigadista raised in the popular Havana barrio Cayo Hueso recounted, "Seeing the way of life of those people, compared with mine, was a shock that has lasted my entire life.18

Additionally, the Literacy Campaign often involved working alongside peasant families in agriculture or other tasks, and marked the first time many urban youths had performed manual or agricultural labor. Castro hoped that the experience would also influence urban youth's understand-ing of the process of production and consumption, and the division of labor between the countryside and the city. In other words, he viewed the partici-pation in agricultural labor as a kind of pedagogy. As he noted:

- You will understand better the relationship between coun-tryside and city; you will understand the need to develop the economy of the countryside to have economic development in the city. You will understand how things consumed in the city come from a farmer's hard work.19

Fidel Castro's goal of exposing urban youths and others to agricultural production also resulted in other initiatives throughout the i960s, such as the "greenbelts" that were established on the outskirts of Havana and the escuelas del campo, programs in which urban school children were sent to a farm for periods of a month or more to undertake agricultural work. Eventually the escuelas del campo and greenbelts were criticized for failing to improve food production and were viewed unfavorably as a way of mobiliz-ing unpaid labor.

Economically, such schemes were indeed failures. But they stand as testa-ment to the idealism and voluntarism that genuinely inspired many Cubans throughout the 1960s by transcending older notions of rural "improve-ment," striving instead for peasant empowerment and even the eventual obliteration of the physical and social boundaries between the city and the country. For example, the agricultural greenbelt (Cordón de la Habana) was viewed by urban planners as facilitating the " fusión entre la ciudad y el campo" (Segre 1989, 63). This and other agricultural initiatives embodied the radical impulse to close the social gulf between urban and rural residents and to disrupt the long-standing division of labor between country and city by pressing urban residents to share the burden of the island's food production. As architect and scholar Roberto Segre wrote optimistically, Havana would lose "la imagen de la ciudad parásito, la 'ciudad-escritorio', la ciudad pasiva" (Segre 1989, 64).

Although many of these programs came to be widely resented by the population of Havana, their political impact on the earliest revolutionary generation remains an open question. Oral histories suggest that many urban Cubans were indeed strongly impacted by those experiences, and at many levels. For example, one woman described her participation as a college student in the Plan de Banao, in Las Villas, an agricultural initiative primarily staffed by women, located in a temperate zone within the Cuban interior that could grow asparagus, strawberries, and grapes.20 She was sent by the University of Havana in the early i960s to simultaneously teach basic subjects to urban prostitutes enrolled in "rehabilitation" schemes, and also to work alongside them in agriculture.

- I'll never forget it. It was first time I saw a strawberry plant. [The first day] the camp leader said, 'Today eat all you want, and tomorrow you won't want any.' The guy was right. That day we ate more strawberries than we picked. After that, we were so sick of strawberries that we could actually pick them! [Later] I also worked picking apples, cleaning aspara-gus leaves... In the sugar harvest of 1970, I worked in the Chaparra sugar mill for six months, and I worked in every position within the mill.21

Young people were also impacted by the radical sense of social equality that could be generated in quasi-militarized agricultural and educational projects. As the participant of the Plan de Banao recalled, "There we were all equals, all equals, from the little rich girl [whose family] had stayed [in Cuba], to the daughter of workers, like me, to whomever else. We all sat at the same table and we were all equal, we slept together, bathed in those beat-up bathrooms, worked in the fields together, and we were all equal. It was a beautiful lesson."22 Struck simultaneously by the hardship of agricultural labor, anecdotes about life in the sex industry, and the enforced absence of social hierarchies, such experiences left strong legacies among the revolu-tionary generation. To the extent that one might criticized these initiatives as partly relying on romanticized notions of a fiercely-independent, morally pure peasantry or the cleansing power of agricultural labor, we might also note that they laid the groundwork for more informed, theoretical discus-sions of the issue of urban-rural solidarity during revolutionary upheavals elsewhere in Latin America.23

FROM COUNTRY TO CITY

If the thrust of many early revolutionary programs was to send young urban Cubans to the countryside, other initiatives brought the "country" to the "city," or at least, brought many peasants to Havana, either briefly for mas-sive public rallies, or for longer stays that involved educational programs or vocational training.

One of the first such instances was the trip of thousands of campesinos, almost entirely men, mostly from the Sierra Maestra region, to Havana for the first massive celebration of the 26 of July in 1959. The date marked the famous attack by Fidel Castro and others on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago, and has subsequently been celebrated as the embryonic creation of the rebel army. Campesinos were transported to Havana to participate in the massive rally that marked the revolution's first year in power. Havana residents were urged to provide the visiting peasants with shelter in private homes, schools, and other institutional spaces. The event was described by the media as a kind of event of national unity, representing the harmony of country and city, symbolically uniting the nation in an emotional expression of revolutionary support. Taking place before the polarization and radical-ization of the revolution, the event drew little criticism. But other programs would have a more lasting and visible impact.

By 1961, longer training programs for campesinos-usually youths- had emerged in Havana. The most famous of these was the Escuela Ana Betancourt, a program to provide vocational training to "muchachas campesinas," as they were always referred to, especially from the interior regions that were then emerging as serious conflict zones. The program was admin-istered through the Federación de Mujeres Cubanas, and was surprisingly large and ambitious. Through the first half of 1961 alone it brought some 6,000 girls to Havana for six-month courses; it may have brought another 6,000 in the second half of the year (Hoy 1961b; 1971). Young girls inhabited group residences in the new "zonas congeladas"-the previously affluent, semi-suburban residential neighborhoods, many residents of which had begun decamping for exile. For example, in 1961, more than 100 residences in the beachfront area Tarará housed some 3,000 girls to receive literacy and training as seamstresses (Hoy 1961a). During the first few years of the revolution in power, thousands-perhaps tens of thousands-of adolescents from the countryside altered the daily life of suburban residential areas such as Tarará, Miramar, Arrojo Naranjo, and Rancho Boyeros.24 Equally symbolic, groups of students from the countryside were lodged in the Hotel Habana Libre, as the Havana Hilton had been rechristened-a state-of-the-art, recently-constructed hotel in a posh central neighborhood of Havana. For example, some of the students of the Escuela Ana Betancourt were put up on three floors of the hotel in 1961, as were the students of agricultural accounting schools, although the practice may have waned by 1963.25

If these peasant training initiatives occasionally echoed the paternalism of pre-revolutionary social work, they also raised, at least implicitly, the notion of the right to the city. Government discourse around the arrival of campesinos for the 26 of July rally of 1959 stressed the sharing of resources with inhabitants of the impoverished countryside, suggesting somewhat patronizingly that habaneros show off the city to their innocent country brethren. At least some of those visitors also felt a sense of connection and personal entitlement upon their first trip to the city. As the young Reinaldo Arenas noted, his first trip to Havana for the 26 of July rally of 1960 marked him profoundly. "We arrived in Havana and the city fascinated me. A real city, for the first time in my life. A city where people did not know each other, where one could disappear, where to a certain extent nobody cared who you were... this first trip to Havana was my initial contact with another world... I felt that Havana was my city; that somehow I had to return" (Arenas 2000, 52).

The revolutionary government also implemented projects to democratize access to public space in the city, including the desegregation of parks and beaches (De la Fuente 2001, 268-269). Early initiatives also decreed the destruction of notorious slums such as Las Yaguas in Havana, La Manzana de Gómez in Santiago, or Los Grifos in Santa Clara, and to build adequate new housing projects for the urban poor on the cleared site or in another designated area.26 These sweeping attempts to destroy the physical class segregation of the city and to implement the right to decent housing were echoed around the Third World in moments of deep reform, revolution and decolonization (Davis 2006, 50-69). In practice, these programs had clear shortcomings. For example, the Cuban government sought to desegregate public space in a way that would minimize conflict, and the inability to construct adequate urban housing eventually led to the reemergence of im-provised squatter settlements and notoriously overcrowded housing projects. Still, such measures changed the social composition of existing spaces, mak-ing them more inclusive and democratic.27

REVOLUTION AND DISAFFECTION

Not surprisingly, the transformations to both city and country in this period were experienced by some Cubans as unwelcome disruptions and were fac-tors leading to the growth of internal opposition. Beyond intentional state-directed efforts to reform urban spaces of leisure and housing and induct rural youths into educational programs located in Havana, the city was also transformed indirectly as a result of both internal class conflict and the ex-ternal conflict with the US. If the change to the relations between country and city is central to understanding the consciousness of some Cubans in this period in this period, it is equally important to understanding the anxi-ety the revolution produced among others.

Following the revolutionary triumph of 1959, Havana witnessed a series of strikes and other demands put forth by labor. Conflict between workers and management culminated in a series of worker-provoked "interventions," followed by nationalizations. These changed the physical aspect of stores and factories, which now bore signs pronouncing the workers' revolution-ary zeal. For example, in spring of 1960 the US-owned Compañía Cubana de Electricidad was draped with a banner describing it as occupied by workers who were "dispuestos a dar la vida por la soberanía nacional"28 Pre-revolutionary Havana streets had been crowded with advertising and the campaign ads of electoral candidates, but the political views of other sectors now found regular expression on the city's walls.

If many habaneros were used to strikes and even worker-inducted government interventions among the laborers of ports, railways, factories, and other urban industries, the spread of interventions and nationalizations to the department stores of Havana's famous downtown shopping thoroughfare was particularly significant, for it indicated the spread of revolutionary conflict to sectors that previously had not been well organized. By fall of 1960, the commercial district of Havana had become the site of sustained mobi-lization and conflict. The nationalization of the major department stores in fall of 1960 left them physically altered, draped with Cuban flags, banners announcing their nationalization, and signs bearing revolutionary slogans hung both inside and out (Zamora 1960; Padula 1974, 324). The public on the streets had also changed, as working-class Cubans enjoyed their new disposable income, and sweeping economic and political changes increased migra-tion from the country to the city. Formerly-exclusive stores now "found themselves physically occupied [materialmente tomada] by a jumbled public, of all ages," as one magazine described it. "A heterogeneous human mass that entered and exited... the different salons of the elegant establishment" (Zamora 1960, 49-50). If these changes were exciting and welcome for some, they were disquieting for others, who found their city's main drags and its shoppers changed beyond recognition.

The downtown commercial area also became the site of high-profile sabotage attempts throughout the winter of 1960 and spring of 1961. One of the most exclusive and emblematic department stores, El Encanto, was destroyed by a firebomb in April 1961, just days before the Bay of Pigs invasion. The destruction of El Encanto had special resonance. A popular refrain had been, "If El Encanto goes down, the country goes down," a saying that captured the equation of consumer culture with modernity for many urban residents (Padula 1974, 325)29 After its destruction, some residents remarked that the city felt disfigured, poor, like a provincial city, as the fiction writer Edmundo Desnoes described it in his novel Memorias del subdesarrollo. "It looks like a city of the interior. It no longer looks like the Paris of the Caribbean. Now it looks like a Central American capital, one of those dead and underdeveloped cities."30

The city center was also indirectly transformed by the mass structural transformations introduced by the revolution. The agrarian reform, nation-alizations of industry, the increase of workers' income especially in rural areas, the centralization of political decision-making, and particularly the conflict with the United States, all altered the flow of consumer goods toward the capital. Increased rural purchasing power combined with the disruption of pre-revolutionary systems of production and distribution to create spo-radic shortages of some food items in the urban centers. The abrupt termina-tion of trade with the United States initiated a crisis in equipment, foodstuff and consumer items that was only slowly ameliorated by trade relations with the Soviet Union.

These changes were immediately visible in the urban fabric, and the changes to their city deeply distressed some habaneros. One man wrote to a friend then working in New York to describe his melancholy at the changes he had witnessed. "The...lovely shop-window displays that we loved to see at night, newspaper, radio and TV advertising, all that has disappeared, my friend! You go into any kind of store and you find the shelves 75% empty and the sales people idle, short-tempered and rude."31 Another man warned a friend that "If you saw the 'La Copa' Commercial Center, you'd cry. On Sunday we went to Guanabo Beach... Everything was closed. it was like a cemetery."32 And a woman reminisced during the Christmas season of 1961, "I remember the Havana of old times, when at this time of year going to the stores was wonderful. Now there is only destruction and sadness." (Bohemia Libre 1962)

These transformations to the city endured. When the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal visited Havana almost ten years later he commented, "Havana at night is a dark city because it has no commercial signs. [I]t could seem sad, if for you happiness is neon lights, shop windows, hustle and bustle, night life" (Cardenal 1972, 14). Of course not all habaneros agreed. Some, at least, must have resented the night life generated by the casinos and hotels bolstered by the growing tourism of the i950s. Indeed, in the immedi-ate aftermath of the revolutionary victory of January i, 1959, casinos were the only establishments that were sacked and burned by Havana crowds.

CONCLUSIONS

The description of Havana as a city in ruins, or a city trapped in time, has become something of a cliché in the international media. It is true that the revolution carried only a few large-scale architectural experiments to completion, such as the Escuela Nacional de Arte or the Coppelia ice cream park, projects that sought to embody socialist values in physical space (Curtis 1993; Loomis 1998). Construction of residential units has likewise not met the city residents' needs, and the housing redistribution undertaken by the early urban reforms were not sufficient to transform extant overlapping patterns of race, privilege, and residence. All in all, the revolution's impact on the physical structures of city probably had more to do with avoiding the negative trends of other twentieth-century cities, such as destruction of the colonial core and the mushrooming of poor peripheral shanties.33

But one could argue that the revolution's major impact was in giving new social meaning to extant spaces and making the city more inclusive in prac-tice. Government initiatives helped redefine which spaces were public, and, indeed, what "public" meant. Yet these changes were not always planned or intentional. In the polarizing atmosphere of the first few years of the revolu-tion, the city itself became a battleground, as stores, workshops and factories were nationalized and sabotage defaced the city's prominent buildings. The campo was re-imagined as a progressive, pure, inspirational space. And the massive human movement from country to city and vice versa helped make the "revolutionary moment" partly a project in breaking down urban-rural barriers. These experiments in subverting the hierarchy of country and city were exhilarating for some Cubans, and disturbing for others. For some young urban participants in literacy and other campaigns, the contact they had with the countryside changed their consciousness permanently. For some country dwellers, the new opportunities opened by the revolution, in-cluding studying or migrating to the city, were life-changing. But for many critics of the revolution, the initiatives smacked of a world upside down, in which middle-class urban children were sent to the countryside for indoc-trination and rustic labor, while peasant girls were being put up in the most luxurious hotels in Havana. That disorientation contributed to the broader sense of a collapsing social world that induced some habaneros to leave their city and seek their futures elsewhere.

Comments

1 References are too extensive to be included exhaustively here, but excellent works on the Mexican, Guatemalan, Bolivian, and Nicaraguan revolutions include Joseph and Nugent 1994; Grandin 2004; Gotkowitz 2007; and Hale 1994. The literature on the Chilean revolution has encompassed an urban focus including the classic work by Peter Winn (1986). Also see Tinsman 2002.

2 Exceptional work on the Mexican revolution in urban centers includes Wood 2001 and Lear 2001.

3 There is a significant literature on the revolution's impact on city structures, often with a focus on architecture and urban planning. See, for example, Segre 1989.

4 For an excellent history of Havana, especially from a perspective of urban planning and architecture, see Scarpaci, Segre and Coyula 2002. Also see Cluster and Hernández 2008 for a narrative history, and García Díaz and Guerra 2002 for an unusual comparative perspective. For an excellent longue duree exploration of Havana history, see Le Riverend 2002.

5 The term is by Huge Thomas, cited in Álvarez-Tabío Alba 2000, 320.

6 Ad printed in Hoy, July 12, 1960.

7 oral history with Nilda, Havana, June 2008.

8 oral history with Luisa, Miami, February 2008.

9 See "The Campaign Against Illiteracy," chapter 3 in Fagen 1969.

10 Fidel Castro speech, reprinted in Hoy, August 12, 1960.

11 Fair Play for Cuba Committee Bulletin, Sept 2, 1960.

12 Hoy, July 26, 1960.

13 Fidel Castro speech, reprinted in Hoy, August 12, 1960.

14 Oral history with Luisa, Miami, February 2008.

15 See "The Campaign Against Illiteracy," chapter 3 in Fagen 1969. v

16 Address by Fidel Castro to the literacy brigades at varadero, May 14, 1961, reproduced in Castro speech database.

17 Oral history with Esperanza García Peña conducted by Lyn smith, Lyn smith Collection, Library of Congress.

18 Oral history with virgen, Havana, June 2008.

19 Address by Fidel Castro to the literacy brigades at varadero, May 14 1961, reproduced in Castro speech database.

20 The program was discontinued in 1967.

21 Oral history with Marta, Havana, June 2007.

22 Oral history with Marta, Havana, June 2007.

23 See for example, Zimmerman 2000 and Chávez 2010.

24 For a case study of transformations to a street in Miramar, see Lewis 1987.

25 See Arenas 2000 and Núñez Machín 1961.

26 See Lewis 1977 on destruction of Las Yaguas.

27 Private, personal spaces were either integrated through nationalization or only gradu-ally integrated. see De la Fuente 2001, 271-273.

28 Visible in photo printed in Hoy, May 14, 1960.

29 on the importance of consumption in Republican Cuba, see Perez 1999.

30 From Memorias de subdesarrollo, cited in Perez 1999, 504.

31 Letter to Manuel saco from oscar, February 3, 1962. Cuban Letters Collection, Tamiment.

32 Letter to Don Carlos [Porfirio] from R., April 25, 1962. Cuban Letters Collection, Tamiment.

33 Havana is now viewed by urban planners as in a relatively good position to restore the city sustainably. see Lerner 2001.

References

Álvarez-Tabío Alba, Emma. 2000. Invención de la Habana. Barcelona: Casiopea. [ Links ]

Arenas, Reinaldo. 2000. Before night falls. New York: Penguin. [ Links ]

Bohemia Libre. 1962. Cartas a Bohemia Libre. Bohemia Libre, January 21. [ Links ]

Cardenal, Ernesto. 1972. En Cuba. Buenos Aires: Carlos Lohlé. [ Links ]

Cardosa Arias, Santiago. 1960. Aquí vienen las Mariana Grajales. Revolución, September 16. [ Links ]

Chávez, Joaquín. 2010. The pedagogy of revolution: Popular intellectuals and the origins of the Salvadoran insurgency, 1960-1980. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University. [ Links ]

Che Guevara. 2006 (1963). Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War. New York: Ocean Press. [ Links ]

Cluster, Dick, and Rafael Hernández. 2008. The history of Havana. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Curtis, James R. 1993. Havana's Parque Coppelia: Public space traditions in socialist Cuba. Places 8 (3): 62-67. [ Links ]

Davis, Mike. 2006. Planet of slums. New York: Verso. [ Links ]

De la Fuente, Alejandro. 2001. A nation for all: Race, inequality and politics in twentieth century Cuba. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Fagen, Richard. 1969. The Transformation of Political Culture in Cuba. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Fernández Soneira, Teresa. 2002. Con la estrella y la cruz: historia de la federación de las juventudes de Acción Católica Cubana. Miami: Universal. [ Links ]

García Díaz, Bernado, and Sergio Guerra. 2002. La Habana/Veracruz, Veracruz/ La Habana: Las dos orillas. Veracruz: Universidad Veracruzana. [ Links ]

Gotkowitz, Laura. 2007. A revolution for our rights: Indigenous struggles for land and justice in Bolivia, 1880-1952. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Grandin, Greg. 2004. The last colonial massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Guerra, Lillian. 2009. "To condemn the Revolution is to condemn Christ": Radicalization, moral redemption, and the sacrifice of civil society in Cuba, 1960. HAHR 89 (i): 73-109. [ Links ]

Hale, Charles R. 1994. Resistance and contradiction: Miskitu Indians and the Nicaraguan State, 1894-1987. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Hoy. 1961a. Alumnas de Ana Betancourt se alfabetizan para el 26. Hoy, July 8. [ Links ]

Hoy. 1961b. Se graduan 800 muchachas de distintas cooperativas. Hoy, July 14. [ Links ]

Hoy. 1971. Catorce mil maquinas para las escuelas de corte y costura. Hoy, June 6. [ Links ]

Joseph, Gilbert, and Daniel Nugent, eds. 1994. Everyday forms of State formation: Revolution and the negotiation of rule in modern Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Le Riverend, Julio. 2002. La Habana: espacio y vida. Madrid: Mapfre. [ Links ]

Lear, John. 2001. Workers, neighbors and citizens: The revolution in Mexico City. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [ Links ]

Lerner, Jonathan. 2001. Viva la restauración. Metropolis, July. [ Links ]

Lewis, Oscar. 1977. Four men. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, Oscar et al. 1987. Living the revolution: Neighbors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Lockwood, Lee. 1969. Castro's Cuba, Cuba's Fidel. New York: Vintage. [ Links ]

Loomis, John. 1998. Revolution of forms: Cuba's forgotten art schools. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Núñez Manchín, Ana. 1961. Ana Betancourt: escuela de corte y costura en el Hotel Nacional. Hoy, July 23. [ Links ]

Padula, Alfred. 1974. The fall of the bourgeoisie: Cuba, 1959-1961. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico. [ Links ]

Perez, Louis Perez. 1999. On becoming Cuban. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Scarpaci, Joseph, Roberto Segre, and Mario Coyula. 2002. Havana: Two faces of the Antillean metropolis. Chapel Hill: Univeristy of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Segre, Roberto. 1989. Arquitectura y urbanismo de la revolución cubana. Habana: Pueblo y Educación. [ Links ]

Tinsman, Heidi. 2002. Partners in conflict: The politics of gender, sexuality, and labor in the Chilean agrarian reform, 1950-1973. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Winn, Peter. 1986. Weavers of revolution: The Yarur workers and Chile's road to socialism. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Wood, Andrew. 2001. Revolution in the streets: Women, workers, and urban protest in Veracruz, 1870-1927. Wilmington: SR Books. [ Links ]

Zamora, Cristóbal. 1960. Los obreros operan por cuesta del Estado las grandes tiendas. Bohemia, November 6. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, Matilde. 2000. Sandinista: Carlos Fonseca and the Nicaraguan revolution. Durham: Duke University. [ Links ]