Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.77 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2013

Negotiating Disarmament and Demobilisation: A Descriptive Review of the Evidence*

Robert Muggah1

Is the Research Director of the Igarapé Institute, a Principal of the SecDev Group, and a professor at the Instituto de Relações Internacionais, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. From Brazil he directs several projects on international cooperation, peace-support operations, transnational organized crime, citizen security and violence prevention, and humanitarian action in non-war settings across Latin America and the Caribbean. He currently oversees the humanitarian action in situations other than war (HASOW) project (www.hasow.org). He also advises the High Level Panel on the post-2015 development agenda, the Global Commission on Drug Policy and is working on designing new applications to track violence with Google Ideas. Dr. Muggah received his DPhil at Oxford University and his MPhil at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex.

For the past ten years Dr. Muggah was research director at the Small Arms Survey (2000-2011), a lecturer at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, and an adviser to the OECD-DAC, UN, and the World Bank. In addition to several books and peer-reviewed articles, recent outputs include chapters for the Human Development Report (2013) for Latin America, Governance for Peace report (2012), editor and author of Stability Operations, Security and Development (New York: Routledge, 2013), the Global Burden of Armed Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). Email: rmuggah@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) are considered a mainstay of peace and stability operations. Yet, there is surprisingly limited critical examination of how they are negotiated in peace processes or grafted into peace agreements. Given the growing criticism over the design and effectiveness of DDR, it is important to take account of the ways in which it is negotiated to begin with, how it is sequenced, what is included and excluded, and the types of alternative arrangements that are intended to promote confidence among parties. Drawing on existing datasets, this article finds that provisions of DDR are present in over half of all documented comprehensive peace agreements and less than ten per cent of all peace accords, protocols and related resolutions. Moreover, conflict mediators and parties to peace talks seldom regard disarmament and demobilisation as preconditions for negotiations, wary of derailing negotiations. They are nevertheless key considerations in relation to wider security sector transformation and transitional justice in the aftermath of war.

KEYWORDS

Disarmament, demobilisation, reinsertion, reintegration, peace agreements, peace process

Negociar el desarme y la desmovilización: una revisión descriptiva de la evidencia

RESUMEN

El desarme, la desmovilización y la reintegración (DDR) son considerados pilares de las operaciones de paz y la estabilidad. Sin embargo, el examen crítico de cómo se negocian en los procesos o se articulan en los acuerdos de paz es sorprendentemente limitado. Dadas las crecientes críticas al diseño y la eficacia del DDR, es importante tener en cuenta las formas en que éste se negocia en un comienzo, su secuenciación, qué se excluye y se incluye, y los tipos de arreglos alternativos dirigidos a promover la confianza entre las partes. Con base en conjuntos de datos ya existentes, este artículo revela que las provisiones de DDR están presentes en más de la mitad de los acuerdos de paz exhaustivos documentados y en menos del diez por ciento de los acuerdos de paz, protocolos y resoluciones relacionados. Además, los mediadores del conflicto y las partes de las conversaciones de paz raras veces consideran el desarme y la desmovilización como precondiciones para las negociaciones, temiendo estropearlas. No obstante, se trata de consideraciones clave para una mayor transformación del sector de seguridad y para la justicia transicional en las secuelas de la guerra.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Desarme, desmovilización, reinserción, reintegración, acuerdos de paz, procesos de paz

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint77.2013.02

Recibido: 1° de agosto de 2012 Modificado: 22 de noviembre de 2012 Aprobado: 4 de febrero de 2013

Introduction

Disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) are widely regarded as a mainstay of twenty-first century peace agreements and related peace support operations. Since the landmark Agenda for Peace (1992) and the Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (2000),2 DDR has been repeatedly emphasised in UN Security Council resolutions, General Assembly declarations and reports of the Secretary General. Prescriptive guidelines, manuals and training materials have been crafted to assist security and development practitioners alike. A growing epistemic community has also emerged to examine DDR policy, practice and outcomes, particularly in relation to the decline in number and intensity of armed conflicts.3 Indeed, most settings involving some form of international or internal armed conflict since the early 1990s have featured some form of controlled disarmament and demobilisation, often consecutively.

While there is widespread consensus about the centrality of DDR in post-conflict settings, there is comparatively less awareness of the ways in which disarmament and demobilisation (D&D) in particular are negotiated and institutionalised. Instead, it is often simply assumed that they are required and emerge on the basis of consensus. Surprisingly, there are few empirical comparative studies that assess how such activities are integrated into peace processes and peace agreements, much less the underlying rationale.4 There is also comparatively little informed policy guidance on how mediators can broker D&D.5 Yet, a greater awareness of these issues is critical to understand and anticipate how states and armed groups bargain and under what conditions either is prepared to lay down arms. This article begins by addressing these and related information gaps with a descriptive review of the evidence.

The article assesses the extent to which D&D (and to a lesser extent reintegration) is present in peace processes and peace agreements. The overarching objective is to determine the prevalence of these two activities, the ways in which they are expressed and emerging alternative formulations. The paper offers some tentative observations on future iterations of D&D and some explanation for why they are not as commonly referred to as many often assume. The first section features a descriptive overview of the nomenclature and terminology in order to demonstrate the diversity of approaches to D&D. Drawing on two key datasets, the second and third sections consider the scale and scope of D&D and related terms in peace agreements and the location of key terms within them. The fourth section considers how these activities are negotiated and the fifth hones in on emerging security practices that appear to be complementing and, in some cases, supplanting D&D.

1. Defining Debates

In order to understand how D&D is negotiated, it is important to first be clear on the definitions of the constituent elements of DDR, on the one hand, and peace agreements, on the other. Often taken for granted, an analytically clear nomenclature is critical to ensuring conceptual clarity and methodological rigor. Indeed, in undertaking an assessment of the content of peace accords and related agreements, one must not restrict the analysis to "disarmament" and "demobilisation" alone, but also consider their alternative formulations and synonyms.6 This is because in many settings "disarmament" and "demobilisation" may themselves be considered loaded and pejorative terms, tantamount to "surrender" or connoting "forcible" action by foreign or victorious forces.

As a result, the expressions may be deliberately excluded even if provisions exist for voluntary and verified arms control or activities to hand over weapons and ammunitions holdings.7 Although there is no consensus definition of "disarmament", it is generally considered to include the controlled collection, documentation, control and disposal of the small arms, ammunition, explosives and light and heavy weapons of combatants (and often also of the civilian population). Disarmament also frequently entails the development of responsible arms management programmes and associated legislation. There is comparatively rich literature on disarmament, arms control and peace negotiations and on the security dilemmas they generate.8 It is also worth pointing out that a number of synonyms are often used for disarmament across different languages, ranging from "practical arms control" and "weapons management" to "weapons collection" and "weapons destruction".9

According to established UN guidelines, demobilisation includes the formal and controlled discharge of active combatants from armed forces or other armed groups.10 The first stage of demobilisation may extend from the processing of individual combatants in temporary centres to the massing of troops in camps designated for this purpose (cantonment sites, encampments, assembly areas or barracks). Confusingly, it may also entail a limited phase of disarmament. The second stage of demobilisation often involves the provision of support packages to the demobilised, which is also often labelled "reinsertion". As in the case of disarmament, there is a wide range of spellings11 and synonyms for demobilisation in peace agreements, including "cantonment" and "warehousing".

Reintegration, although not addressed in detail in the present article, generally applies to the final stages of a DDR process12 and includes the process by which ex-combatants acquire civilian status and gain sustainable employment and income. It may also entail the provision of a support package, as noted above (described as reinsertion), and include a period of "rehabilitation". Peace agreements on occasion include provisions for the "re-integration" of former combatants into the security services of a given state or their "reintegration" into civilian life.13 It should be stressed that there is a wide range of synonyms to describe the processes of reinsertion, rehabilitation and reintegration, most of which are frequently poorly defined, if at all.14

It is important to also note that a comprehensive peace agreement (CPA) is often described as a written document produced through negotiation. These agreements are effectively prescriptive contracts intended to end or transform armed conflicts. A CPA is comprehensive in that (1) the major parties in the conflict are involved in the negotiation process and (2) substantive issues underlying the dispute are included in negotiations. A CPA is defined by the process and product of negotiations, not the implementation or impact of the written document. In other words, an agreement can still be considered to be comprehensive even if it does not lead to a comprehensive peace. By way of contrast, many types of peace agreements are not comprehensive, including treaties, accords, protocols, pacts and ceasefire agreements. Depending on the definition and database consulted, and as the following section makes clear, there were anywhere between 37 and 640 peace agreements since 1989.

2. The Scale and Scope of Disarmament and Demobilisation Provision

Assuming a measure of agreement on the definitions given above, it is possible to begin assessing the ways in which the D&D processes are (not) accounted for in peace agreements. In order to do so, it is important first to consider the scale and breadth of peace agreements and then the extent to which key provisions are included. Literally, hundreds of peace agreements have been signed since the end of the Cold War, of which a considerable number include provisions for everything from arms embargoes, sanctions and amnesties to DDR and wider security sector reform (DeRouen et al. 2009). Moreover, virtually every UN peace support operation has featured a mandate to undertake forced or voluntary disarmament: there have been no fewer than 60 distinct DDR campaigns since 1989 (Muggah 2009).15

Indeed, there is an expanding research community devoted to studying the relationship between peace agreements and the duration of peace (Darby 2001; Fortna 2004; Hartzell and Hoddie 2007; Hill 2004). Few researchers, however, have focused specifically on the relationship between peace agreements and provisions for D&D and other related concepts. There are, in contrast, a number of searchable datasets of peace agreements that can be used to this end: (1) the Peace Processes and Peace Accords (PPPA) database (37 CPAs between 1989 and 2012);16 (2) the Transitional Justice Peace Agreements (TJPA) database (640 peace agreements between 1989 and 2012);17 and (3) the Uppsala Conflict Data Programme Peace Agreement database (144 agreements between 1989 and 2005).18 Each of these datasets offers different inclusion and exclusion criteria and contrasting mechanisms for conducting searches.

At the outset, the PPPA database includes some 37 separate comprehensive agreements between since 1989.19 While not necessarily exhaustive (and thus representative), it allows for a search of all separate agreements across 51 distinct subject areas, including whether terms and conditions for "disarmament", "demobilisation" and "reintegration" are explicitly included in the content of specific agreements. It does not allow for searches for other synonyms or alternative spellings. Even so, the PPPA database allows for a full textual review of the peace accords and timelines for the implementation of key provisions. The value of the dataset is that it allows for thematic, temporal and spatial analysis. A limitation is that it restricts the nature of the search to preselected search terms, obviating the possibility of examining different spellings, word combinations or languages.

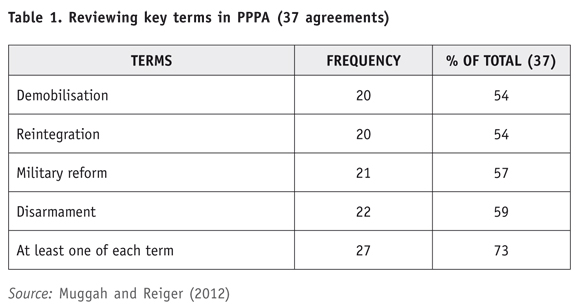

Overall, the PPPA database reveals that over half of all CPAs include explicit provisions for "disarmament", "demobilisation", "reintegration" or some combination of the three (see Table 1). Indeed, 22 of 37 countries - Angola, Bangladesh, Burundi, Cambodia, Croatia, Djibouti, El Salvador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Liberia, Macedonia, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste and Britain - featured these concepts explicitly in the text of CPAs. Intriguingly, three countries did not include provisions for disarmament at all: Djibouti, the Philippines and South Africa.20 In other words, there is significant focus on D&D issues in comprehensive agreements.

Table 1.

By way of comparison, the TJPA database includes 640 separate peace agreements (including CPAs) across 85 separate states and territories. Unlike the PPPA dataset, it allows for a much more flexible search function and is not tied to pre-selected subject headings. Yet, a search of the database for "disarmament" suggests that just 12 peace agreements, protocols, accords and pacts include explicit provisions. These are Burundi (2002), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (1999), Georgia/Abkhazia (1994), Guatemala (1996), India/Pakistan (1999), Liberia (1991, 1993), Niger (1997), Sierra Leone (1997, 1999), Somalia (1993) and Tajikistan (1997). A search for "weapons" and "ammunition" extends the total to 24, since El Salvador (1992, 1993, 1994), India/Tripura (1993), Iraq/Kuwait (1991), Nepal (2006), Papua New Guinea (2000, 2001), Russia/Chechnya (1996), the Solomon Islands (1999) and Britain/Northern Ireland (2001, 2004) are also included.

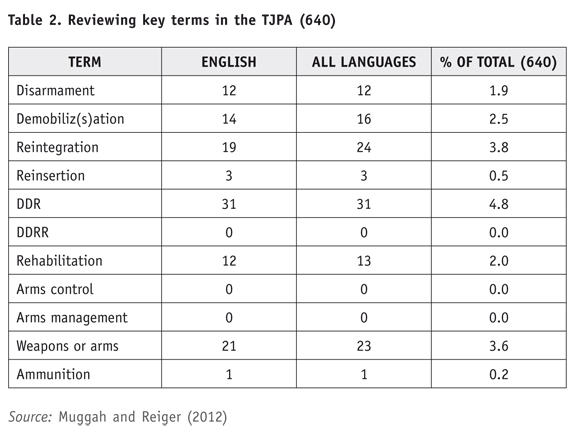

The TJPA dataset also lists additional references to "demobiliz(s)ation", "reintegration" and "DDR". A search for categories of demobilisation and reintegration revealed an additional 24 agreements of various types. In the case of "demobiliz(s)ation", 16 agreements included Burundi (2003), Colombia (1994, 2004), El Salvador (1994), Guatemala (1991, 1996), Nicaragua (1990) and Sierra Leone (1996).21 For "reintegration", an additional 20 agreements from Djibouti (1994, 2000), El Salvador (1991, 1992, 1993), Guatemala (1994), Mozambique (1991, 1992), Nicaragua (1990), Niger (1994, 1995), Rwanda (1992), Sierra Leone (1997, 1999) and Tajikistan (1995, 1997) are also included.22 A final search for "DDR" revealed an additional 31 agreements, including Cambodia (1991), the Central African Republic (1998), Colombia (1991, 1993, 2003, 2004), Côte d'Ivoire (2003, 2005), the DRC (2002), Georgia/Abkhazia (1999), Guatemala (1994, 1995), India/Bodoland (2003), Indonesia/Aceh (2000, 2001, 2005), the Philippines (1998) and Sudan (2004, 2006).23

Table 2.

Thus, taken together, the TJPA dataset includes some 66 distinct peace agreements or other associated protocols, accords and ceasefires with at least one explicit provision for DDR. In other words, roughly 10% of all reported documents include provisions for DDR. As noted in Table 2, peace agreements often address various aspects of DDR and not necessarily always in a unified manner. What is noteworthy is not just the scale, but the geographic distribution of these agreements, with countries in Central and South America, sub-Saharan and North Africa, South and Southeast Asia and the South Pacific represented. Missing from this sample, however, are examples from the former Yugoslavia, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and Serbia and Montenegro.

3. Location and Emphasis of D&D in Peace Agreements

It appears that disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration all figure prominently in comprehensive peace agreements, but less frequently in all manner of accompanying accords, protocols and pacts.

The overall frequency appears, in fact, to be lower than is often implied by many in the United Nations.24 For example, the Department for Peacekeeping Operations has stressed that "[d]isarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) has become an integral part of post-conflict peace consolidation" and that its activities represent "crucial components of both the initial stabilization of warn-torn societies as well as their long-term development". Moreover, it emphasises that "DDR must be integrated into the entire peace process from the peace negotiations through peacekeeping and follow-on peacebuilding activities".25 In order to determine the relative emphasis attributed to these concepts within peace processes, an effort was made to more closely examine the content of a selection of agreements. To this end, the 37 agreements listed in the PPPA dataset were subjected to closer scrutiny to determine the location and relative weight accorded to key concepts. A summary of the key agreements is noted below. It should be emphasised that this assessment is cursory and provisional; the list is not necessarily representative, and it is likely that key concepts feature more regularly in recent peace agreements since 2005 (e.g. South Sudan).

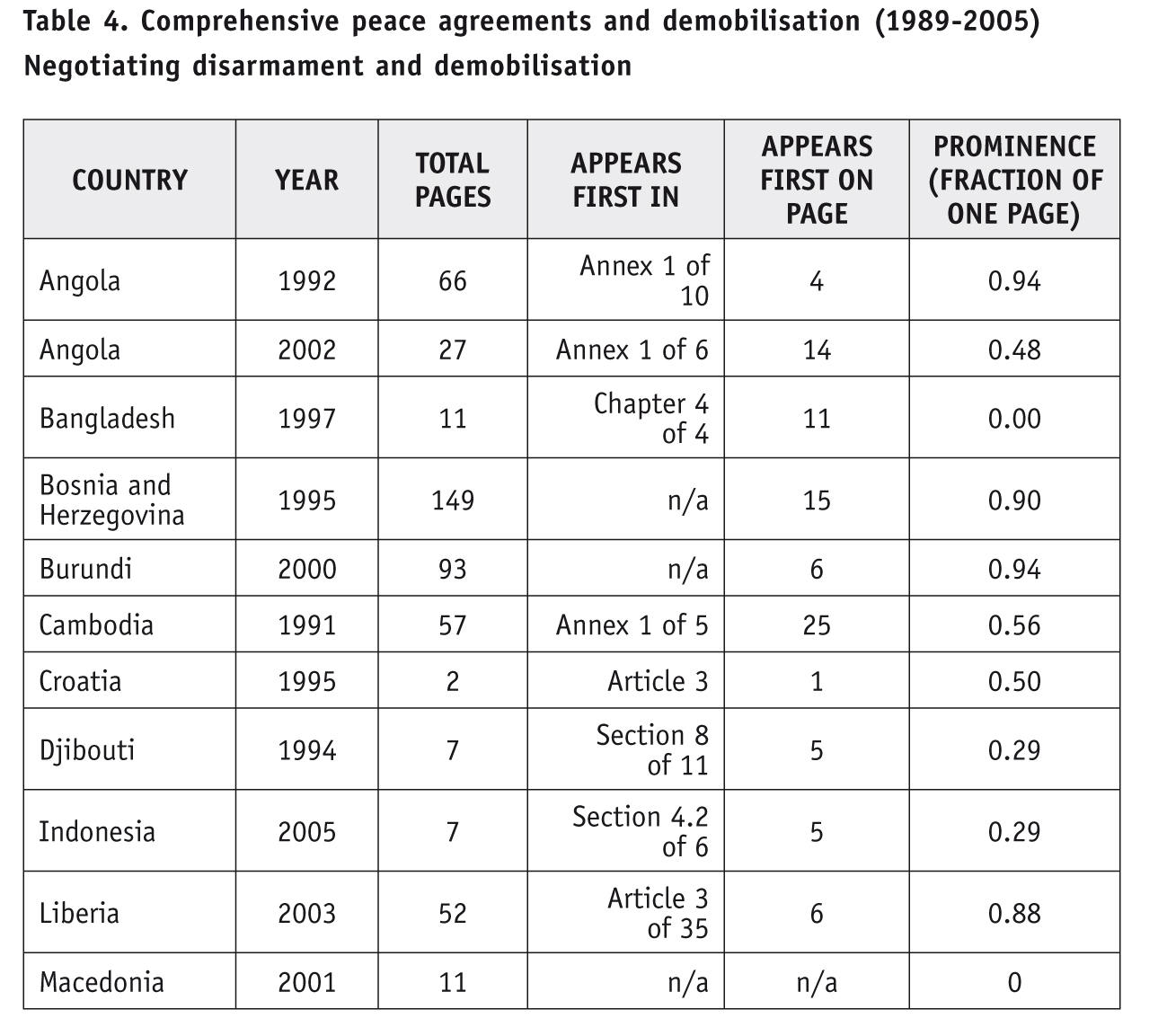

From the descriptive assessment, there does not appear to be a clear, discernible pattern in the distribution of "disarmament" across CPAs. For example, in countries where clear provisions exist, the allusion to disarmament tends to be located predominantly in the middle and end of agreements, occasionally appearing on the first page (e.g. Croatia, Macedonia), but more often emerging midway through (e.g. Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Djibouti, Indonesia, Liberia, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Tajikistan) or nearer the end of the text (e.g. Bangladesh, Cambodia, Timor-Leste and Britain). It is also worth stressing that comparatively limited text is given over to the discussion of disarmament, with no single peace agreement providing more than the equivalent of one page in total (see Table 3). From the perspective of negotiators, then, there does not seem to be any common approach to how disarmament is weighted or located in peace agreements. It is also difficult to know whether the limited references to disarmament (or non-prominent location) are related to the sensitive nature of the issue or to the limited importance accorded to it.

Table 3.

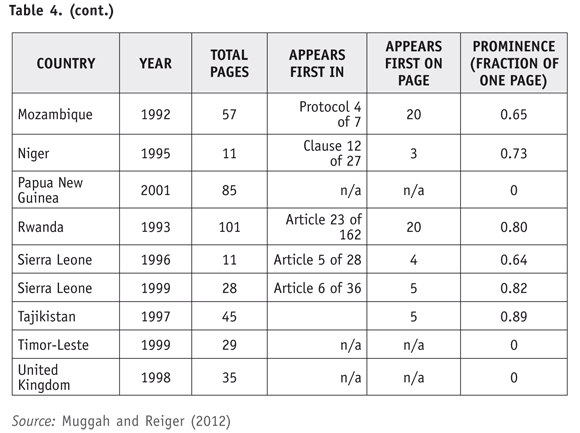

Unsurprisingly, then, there also does not appear to be a clear pattern in the way that "demobilisation" is distributed across CPAs. For example, there are cases in which demobilisation is cited in the first few pages of the document (e.g. Angola, Burundi, Croatia, Niger, Sierra Leone and Tajikistan), but it is also often the case that the term emerges mid-way through (e.g. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Liberia, Mozambique and Rwanda) or closer to the end (e.g. Bangladesh, Cambodia, Djibouti and Indonesia). It should be stressed that, as in the case of disarmament, comparatively little prominence is accorded to demobilisation, with most peace agreements allowing less than one page to the concept and others not doing more than simply using the term a single time (see Table 4). The same caveats for disarmament above apply to interpreting findings on demobilisation.

Table 4.

4. Negotiating Disarmament and Demobilisation

There is great variability in the ways in which security issues related to the management of arms and former combatants are treated in peace processes and peace agreements. The route is often far from straightforward, and most mediators acknowledge the centrality of timing and levels of engagement. Common to all processes, however, is the fact that the D&D of armed groups is an intensely political process involving a series of tactical tradeoffs and symbolic interventions. Thus, while frequently cast as a "technical" process involving a predictable and mechanical exchange of weapons and the cantonment of combatants, D&D initiatives are often hotly contested and routinely fall short of expectations (Muggah 2009). Whether central to the peace process - as in Northern Ireland - or peripheral, the issues of D&D are frequently connected to fundamental priorities associated with the transformation of security and justice systems and transitional and restorative justice (Muggah 2009).

Peace mediators are conscious of the ways in which the dynamics of the armed conflicts influence the direction and dynamics of D&D (Muggah 2013; Colletta and Muggah 2009). Specifically, how a given armed conflict was initiated, pursued and terminated will influence whether and how warring parties disarm or volunteer their cadres for demobilisation and reintegration. If there is a clear victor in an armed conflict, or if soldiers are returning home after waging a cross-border conflict, the terms for D&D may be more straightforward. If an uneasy truce is achieved as a result of a hurting stalemate, then negotiations are likely to be more fraught. For example, during the 1990-92 negotiations between the El Salvadorian government and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), "disarmament" was the last item on the agenda. Indeed, the FMLN insisted on a full "political agreement" before discussing disarmament.26

There are often acrimonious disagreements between groups about pursuing D&D as a precondition for peace talks. Indeed, armed groups ranging from the Nepal Maoists and the Philippines-based Moro National Liberation Front to the El Salvadorian FMLN also rejected demands that disarmament should precede negotiations, let alone demobilisation. This is because disarmament is an intensely political issue and linked to a widely recognised security dilemma for parties involved in or emerging from armed conflict (Knight and Ozerdem 2004; Nussio 2011). Without transparent and credible guarantees that the terms of a peace agreement will be enforced and the security of disarmed parties will be ensured, the rational response is to decline the handing over of armaments or the demobilisation of one's forces. As noted by the former head of the Colombian M-19 movement, "Laying down our arms was, to many of us, unthinkable, as we feared treason and the uncertainties of a future without the availability of weapons as an 'insurance policy'. We had not realized that peace needed to become a one-way journey ... the transition to civilian life risked the end of life as a group, but also an identity forged on the use of arms" (Buchanan & Widmer 2006).

The effectiveness of DDR - particularly D&D - is inextricably connected to the types of security arrangements that are put in place. If "voluntary" disarmament is to be pursued, it is vital that any efforts be accompanied by a combination of clear communications and awareness-raising activities about the intent and purpose of the interventions and routine confidence-building measures to show progress. Too often, disarmament is left to the last minute, the legal and programmatic practicalities are poorly communicated and the process results in confusing and contradictory messages being communicated to the public. Moreover, since many of the "beneficiaries" of DDR activities were at one stage on the front line and may themselves have committed atrocities, legitimate concerns are often raised about the justice and ethics of providing support. Human rights advocates and community leaders often fear that, in the pursuit of security dividends, fundamental issues of transitional justice and community reconciliation are compromised (Sriram and Herman 2009).

It is also important to acknowledge the culturally and socially specific functions of weapons and armed groups in societies when considering provisions for D&D. Indeed, mediators should understand the dynamic social and historical functions of weapons, including when weapons ownership is symbolic and associated with adulthood and community responsibility (Ong 2012). For example, in Northern Ireland, the constitution of the IRA explicitly cites the use of violence as a means of advancing the organisation's struggle and has been interpreted as prohibiting the group from accepting disarmament. Likewise, in Afghanistan, the central place of weapons in society encouraged DDR planners to design reintegration programmes that did not require full disarmament. Incentives were instead provided to individual insurgents and their communities that sided with the government (Ong 2012). What is more, in many societies weapons are collectively rather than individually owned, as in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and South Sudan. In such situations, it may be unrealistic and even dangerous for mediators to seek full disarmament, since partial disarmament may leave entire communities or ethnic groups vulnerable to attacks from neighbours (Muggah 2004b).

Other challenges facing DDR are usually administrative and bureaucratic. For example, the UN and others have frequently had a difficult time undertaking successful DDR because of disagreements and confusion over mandates and budgets. The recent efforts by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and the UN Development Programme (UNDP) to pursue an "integrated" approach confronted some challenges, as experiences in Haiti and Sudan can attest (Muggah 2007). In both cases, a lack of clarity over the direction, terminology and organisation of DDR resulted in the breakdown of efforts to collaborate. In some cases, the host government and the armed groups themselves may also try to disrupt the process. In most cases, DPKO is responsible for undertaking D&D of former combatants, while UNDP, the World Bank and the International Organisation for Migration support everything from civilian disarmament to reinsertion and reintegration. The so-called Integrated Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Standards (IDDRS) established by an inter-agency working group of more than 16 UN agencies are intended to clarify roles and responsibilities, but these are not always observed.27 Too often, gaps emerge in which funding for critical facets of DDR go unsupported and the programme stalls.

It is important to stress that there are no magic bullets for all the many security dilemmas arising in a post-conflict period, even if D&D are frequently described as such. Even so, the progressive decline of armed conflicts around the world since the late 1980s suggests that these and other activities have potentially played a positive role in promoting safety and consolidating peace. However, over the past decade, many alternative security promotion activities have emerged that have also yielded important reductions in armed violence. For example, community security activities, interventions focusing on at-risk youth, weapons-for-development programmes and specialised urban renewal schemes are examples of innovative practice and are increasingly described as "second-generation" DDR (DPKO 2010). A key lesson, then, is the importance of taking into account multiple possibilities to promote peace in the aftermath of war rather than always resorting in a kneejerk fashion to DDR or some related combination.

5. Emerging Alternatives to D&D

A number of best practices for DDR and related D&D activities are emerging. Some of these are set out by the aforementioned inter-agency UN working group in the IDDRS.28 These guidelines were initiated in 2004 and continue to evolve as lessons are learned.29 In the case of peace negotiations and agreements in South Sudan, for example, they were applied to set out a rightsbased set of prescriptions to deal with the handing in of weapons, child protection and preferences for "community-based" approaches to reintegration (Baare 2008). For example, some recent work on interim stabilisation and second-generation DDR has been integrated into the IDDRS, as well as the work of specialised UN agencies such as DPKO and UNDP, which have advanced "community security and social cohesion", "community violence reduction" and "armed violence reduction" strategies.30

A number of issues are often taken into consideration when it comes to post-conflict D&D and other security arrangements. Firstly, there is a consensus that provisions for arms control and the management of former combatants should be highlighted in peace accords and agreements wherever possible. These are critical to setting out the "rules of the game" and, if informed by the standards set out by the IDDRS, can also potentially ensure that key provisions related to gender equity and minority inclusion are grounded early in negotiations. Secondly, although difficult to achieve in practice, there is agreement that a clear and transparent selection process is required for possible demobilisation and reintegration candidates in order to avoid inflating the expectations of would-be participants or generating conflict among non-beneficiaries. Thirdly, a balance of individual and collective incentives and monetary and non-monetary packages is needed, depending on the setting. These should be provided over time and with some degree of accompaniment and oversight to avoid moral hazard and wastage. Finally, most experts acknowledge that the "reintegration" component is often the least well-managed and financed.31 Notwithstanding the abovementioned principles and norms designed to guide DDR planning and practice, a key lesson from past efforts is that context determines everything (Muggah and Krause 2010). As noted above, the way a country's armed conflict is ended and mediated, and the shape of its political institutions, economy and social fabric, are critical factors that shape a society's disposition to disarm and demobilise. The way in which a peace process is managed and the extent to which warring groups and civil society are involved in peacebuilding are equally critical factors. In other words, DDR cannot simply be "grafted on" to a post-conflict setting. It is not merely a technical processan interim mechanism required before elections and wider development activities are resumed. Rather, it constitutes a highly political set of activities that must be preceded by a clear political settlement lest they be seen as increasing the security of one group at the expense of another.

Conclusions

There appear to be fewer provisions for DDR in peace agreements than often assumed by its supporters. Indeed, this report has found that there are provisions for a range of related concepts in roughly half of all CPAs since 1989. Yet, similar terms feature in fewer than 10% of a much larger group of peace accords, protocols and ceasefires over the same period. What is more, the placement of key concepts is highly variable, with most peace agreements featuring provisions for D&D in the middle or later parts of the document(s). From this preliminary assessment, it seems that there are no golden rules for when and how provisions for these concepts should be pursued. A wide range of synonyms and expressions for DDR hinder an exhaustive treatment of the subject.

Indeed, comparative research is frustrated by the sheer range and multiplicity of expressions - arms control, weapons management, micro-disarmament or practical disarmament, etc. - and languages in which peace agreements are crafted. It is important to note that negotiators and parties to conflicts frequently object to the terminology of "disarmament" and "demobilisation" precisely because the terms connote a form of submission or surrender. In some cases, these concepts are left out entirely or substituted with less offensive terms. Often, ambiguity is intentional in order to avoid derailing carefully crafted processes.

The negotiation experiences of mediators and parties to conflicts reveal that D&D are highly political processes. In some cases, these issues are relegated to the ends of talks, since they are fundamentally connected to wider discussions on the architecture of the security sector, the distribution of power and wider issues of criminal and transitional justice. Owing to their highly political nature, it is not advisable that full D&D be necessarily made preconditions of negotiations. Indeed, there is ample evidence from past peace agreements that they were specifically excluded or replaced with alternative concepts. Even so, an emerging set of good practices suggests that they should nevertheless be discussed openly and that a wide range of "security promotion" practices be considered alongside conventional DDR. Examples of second-generation iterations and interim stabilisation efforts are increasingly becoming better known.

Comentarios

* This paper was originally prepared as a policy report for the Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Center and benefited from the research assistance of Matthias Rieger and editorial support of the Center for Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding (CCDP).

1 This article is based on Muggah and Reiger (2012). Special thanks are reserved for the research assistance of Mathias Reiger and the support of CCDP and NOREF.

2 See UNSG (1992) and UNSG (2000).

3 For a review of the literature, see Berdal and Ucko (2009), Muggah (2009), and Muggah (2005).

4 The Escola de Cultura de Pau features some limited anecdotal information on how DDR issues are accounted for during negotiations. See Caramés and Sanz (2009).

5 There are, however, some notable exceptions. See, for example, Ong (2012).

6 Note that disarmament and demobilisation could also be described as arms control and cantonment. Likewise, in French, Portuguese, Spanish or other languages, the concepts are obviously spelt differently. A full search for the purposes of research would, thus, require searching with British and US spelling, as well as in multiple languages. Likewise, in many cases, concepts such as reinsertion, rehabilitation and recovery are often added, resulting in abbreviations for the process such as DDRR, DDRRR and DDRRRR. On the proliferation of Rs, consult Nilsson (2005) and Muggah (2004a).

7 For example, the use of the concept of disarmament almost derailed major negotiations, including the Bonn Agreement and the Nepal peace process. Thus, wording in the Bonn Agreement was changed to the following: "Upon the official transfer of power, all mujahideen, Afghan armed forces, and armed groups in the country shall come under the command and control of the Interim Authority, and be reorganized according to the requirements of the new Afghan security and armed forces."

8 The United Nations has also published a series of reports on related issues since the mid-1990s. See, for example, Ginifer (1995) and Adibe (1995).

9 For example, "disarmament" is also spelt as désarmement, desarme, disarm, desarmamento, controle des armes, gestion des armes, controle de armas, gesato de armas, gestion de las armas, etc.

10 See Module 4.20 of the IDDRS. For a more academic treatment, consult Knight and Õzerdem (2004).

11 For example, "demobilisation" is spelt demobilization, desmobilização, desmovilización and the like.

12 See Module 4.30 of the IDDRS.

13 This, in some ways, reflects the "nexus" between DDR and Security Sector Reform. See, for example, Bryden (2007, 29) and Lamb and Dye (2009).

14 Synonyms include reinsertion, rehabilitation, reintegração, reinserção, reabilitação, reintegración, reinserción and rehabilitación.

15 The first UN-sanctioned intervention combining the hand-over of weapons, the cantonment of former combatants and their reinsertion and reintegration into civilian life occurred three decades ago in Namibia. Many more soon followed across sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, Southeast Europe, South and Southeast Asia, and beyond. Although the UN remains the chief proponent of post-conflict DDR, many other agencies ranging from the World Bank to bilateral development agencies are involved.

16 See Peace Accords Matrix, https://peaceaccords.nd.edu/.

17 The dataset includes proposed agreements not accepted by all relevant parties (but setting a framework); agreements between some but not all parties to conflicts; agreements essentially imposed after a military victory; joint declarations largely rhetorical in nature; and agreed accounts of meetings between parties even where these do not create substantive obligations. In cases where a series of partial agreements were later incorporated into a single framework agreement, all of the constituent agreements are listed separately. Where specific pieces of legislation, constitutions, interim constitutions, constitutional amendments or UN Security Council resolutions were the outcomes of peace negotiations, these are included in the database; however, where these were viewed as far removed from the peace agreement, they were not included. See http://www.peaceagreements.ulster.ac.uk/.

18 The author elected not to assess the UCDP dataset owing to methodological constraints in disaggregating fields. See http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/ program_overview/current_projects/ucdp_peace_agreements_project.

19 The last peace agreement included in the dataset is Cote D'Ivoire in 2007.

20 South Africa (1990 ceasefire and 1993 peace accord), the Philippines (1993 ceasefire and 1996 peace agreement) and Djibouti (1994 ceasefire and 1994 peace agreement) excluded "disarmament" from their peace agreements, opting instead for "demobilisation" and "reintegration".

21 Note that Burundi (2002), Liberia (1993) and Sierra Leone (1997, 1999) also included provisions for demobilisation and reintegration.

22 Also included in the reintegration category were Burundi (2002), El Salvador (1994), Guatemala (1991) and Sierra Leone (1996).

23 Also included under DDR were Burundi (2002), the DRC (1999), Liberia (2003), Sierra Leone (1999), Tajikistan (1997) and Britain/Northern Ireland (2001).

24 See Ong (2012) and http://www.government.se/content/1/c6/06/54/02/2ddc4267.pdf.

25 See, for example, http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/issues/ddr.shtml.

26 Likewise, issues of civilian arms control, demobilisation and reintegration were also relegated to later stages of the negotiations. See Buchanan and Chavez (2009).

27 See IDDRS.

28 Consult IAWG (2011).

29 Modules on DDR and security sector reform have been recently introduced.

30 The World Bank is also frequently involved in supporting national and regional DDR activities, although it is statutorily restricted from becoming involved specifically in disarming warring parties.

31 See IDDRS.

References

1. Adibe, Clement. 1995. Managing arms in peace processes: Somalia. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

2. Baaré, Anton. 2008. Negotiating security issues in the Juba process, ed. C. Buchanan, Negotiating disarmament 2: 20-32. Geneva: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. [ Links ]

3. Berdal, Mats and David H. Ucko (eds.). 2009. Reintegrating armed groups after conflict: Politics, violence and transition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

4. Bryden, Alan. 2007. Understanding the DDR-SSR nexus: Building sustainable peace in Africa. Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces 29. [ Links ]

5. Buchanan, Cate and Joaquín Chavez. 2009. Negotiating disarmament: Guns and violence in the El Salvador peace negotiations. Geneva: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. [ Links ]

6. Buchanan, Cate and Mireille Widmer. 2006. Negotiating disarmament: Reflections on guns, fighters and armed violence in peace processes. Geneva: Geneva Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. [ Links ]

7. Caramés, Albert and Eneko Sanz. 2009. DDR 2009. Analysis of DDR programmes in the world during 2008. Barcelona: Escola de Cultura de Pau. [ Links ]

8. Colletta, Nat J. and Robert Muggah. 2009. Context matters: Interim stabilization and second generation approaches to security promotion. Conflict, Security and Development 9 (4): 425-453. [ Links ]

9. Darby, John. 2001. The effects of violence on peace processes. Washington, DC: USIP. [ Links ]

10. DeRouen, Karl, Jenna Lea, and Peter Wallensteen. 2009. The duration of civil war peace agreements. Conflict Management and Peace Sciences 26 (4): 367-387. [ Links ]

11. DPKO. 2010. DDR in retrospect. New York: DPKO, http://www.un.org/en/peacekee-ping/publications/ddr/ddr_062010.pdf. [ Links ]

12. Fortna, Virginia P. 2004. Peace time: Cease-fire agreements and the durability of peace, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

13. Ginifer, Jeremy. 1995. Managing arms in peace processes: Rhodesia/Zimbabwe. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

14. Hartzell, Caroline A. and Matthew Hoddie. 2007. Crafting peace: Power-sharing institutions and the negotiated settlement of civil wars. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [ Links ]

15. Hill, Stephen M. 2004. United Nations disarmament processes in intra-state conflict. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

16. IAWG. 2011. The new operational guide to the integrated disarmament, demobilization and integrated standards. http://unddr.org/documents.php?doc=1284. [ Links ]

17. Knight, Mark and Alpaslan Ozerdem. 2004. Guns, camps and cash: Disarmament, demobilization and reinsertion of former combatants in transitions from war to peace. Journal of Peace Research 41 (4): 499-516. [ Links ]

18. Lamb, Guy and Dominique Dye. 2009. Security promotion and DDR: Linkages between ISM, DDR, and SSR within a broader peacebuilding framework. In CIDDR Conference. Cartagena. [ Links ]

19. Muggah, Robert. 2004a. The anatomy of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration in the Republic of Congo. Conflict, Security and Development 4 (1): 21-37. [ Links ]

20. Muggah, Robert. 2004b. Diagnosing demand: Assessing the motivations and means for firearms acquisition in the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Discussion. Paper no. 2004/7. [ Links ]

21. Muggah, Robert. 2005. No magic bullet: A critical perspective on disarmament, demobilization and reintegration and weapons reduction during post-conflict. The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs 94 (379): 239-252. [ Links ]

22. Muggah, Robert. 2007. Great expectations: (Dis)integrated DDR in Sudan and Haiti. Humanitarian Exchange Magazine 40. [ Links ]

23. Muggah, Robert. (ed.). 2009. Post-conflict security and reconstruction: Dealing with fighters in the aftermath of war. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

2 4. Muggah, Robert. (ed.). 2013. Stabilization operations, security and development: States of fragility. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

25. Muggah, Robert and Keith Krause. 2010. Closing the gap between peace operations and post-conflict insecurity: Towards a violence reduction agenda. International Peacekeeping 16 (1): 136-150. [ Links ]

26. Muggah, Robert and Mathias Reiger. 2012. Negotiating disarmament and demobilisation in peace processes: what is the state of the evidence? Oslo: NOREF. [ Links ]

27. Nilsson, Anders. 2005. Reintegrating ex-combatants in post-conflict societies. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. [ Links ]

28. Nussio, Enzo. 2011. Learning from shortcomings: The demobilisation of paramilitaries in Colombia. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development 6 (2): 88-92. [ Links ]

29. Ong, Kelvin. 2012. Managing fighting forces: DDR in peace processes, Washington, DC: USIP, http://www.usip.org/p.ublications/managing-fighting-forces-ddr-in-peace-processes. [ Links ]

30. Schulhofer-Wohl, Jonah and Nicholas Sambanis. 2010. Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programs: An assessment. Folke Bernadotte Academy Research Report, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1906329. [ Links ]

31. Sriram, Chandra L. and Johanna Herman. 2009. DDR - and transitional justice: Bridging the divide? Conflict, Security & Development 9 (4): 455-474. [ Links ]

32. United Nations Secretary General (UNSG). 1992. An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peacekeeping. A/47/277, 17 June. [ Links ]

33. United Nations Secretary General (UNSG). 2000. Report of the panel on United Nations peace operations, A/55/305, 21 August. [ Links ]