Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Colombia Internacional

versión impresa ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.81 Bogotá mayo/ago. 2014

Free Trade and Labour and Environmental Standards in MERCOSUR*

María Belén Olmos Giupponi**

** Holds a PhD in Law, a Masters in Human Rights from Universidad Carlos III (Spain) and a Masters in International Relations from the Advanced Studies Centre (Argentina). Currently, she is a Lecturer at the University of Stirling (Scotland). Her research has been featured in journals in the fields of economic integration and cooperation, human rights and environmental law. She was a Max Weber Postdoctoral Fellow at the European University Institute (2007-2009) and, previously, a Research Fellow at the Istituto di Studi Giuridici Internazionali, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, (Intaly) in 2006 and at the Centre de Recherche sur les Identités Nationales et lInterculturalité (CRINI) of the University of Nantes (France) in 2005. She is the author and editor of various books, including The Law of MERCOSUR (co-edited with Marcílio Franca Filho and Lucas Lixinski), Oxford and Portland: Hart, 2010. E-mail: m.b.olmosgiupponi@stir.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

The main argument put forward in the article is that MERCOSUR accommodated the protection of human rights as non-trade issues in its institutional framework, analysing the conflict between the protection of human rights and trade issues at the sub-regional level. In order to give a complete and clear picture of these developments, the paper examines member states' constitutional provisions and the implementation of MERCOSUR labour and environmental standards before national courts.

KEYWORDS

Free trade agreements, human rights, sub-regional integration processes, labour rights, environmental protection, MERCOSUR

Tratados de Libre Comercio y derechos laborales y medioambientales en Mercosur

RESUMEN

El artículo señala cómo Mercosur ha incorporado la protección de los derechos humanos como un aspecto no comercial en su marco institucional de integración. Con el fin de dar una imagen completa y clara de esta incorporación, la autora examina, por medio de un análisis socio-legal, las disposiciones constitucionales de los Estados miembros y la aplicación de las normas laborales y ambientales de Mercosur ante los tribunales nacionales.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Acuerdos de libre comercio, derechos humanos, integración regional, derechos laborales, protección del medioambiente, Mercosur

Tratados de Livre Comércio e direitos laborais e meio ambientais no Mercosul

RESUMO

Este artigo indica como o Mercosul vem incorporando a proteção dos direitos humanos como um aspecto não comercial em seu marco institucional de integração. Com o objetivo de dar uma imagem completa e clara dessa incorporação, a autora examina, por meio de uma análise sociolegal, as disposições constitucionais dos Estados membros e a aplicação das normas laborais e ambientais do Mercosul ante os tribunais nacionais.45

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Acordos de livre comércio, direitos humanos, integração regional, direitos laborais, proteção do meio ambiente, Mercosul

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint81.2014.03

Received: September 24, 2012 Accepted: January, 2013 Revised: January 10, 2014

Introduction1

Traditionally, free trade agreements (FTAs) among developing countries in Latin America focused only on economic matters. However, the "new regionalism" that emerged in the 1990s moved towards the inclusion of social clauses requiring member states to observe certain labour and environmental standards. In particular, sub-regional integration agreements2 incorporated these standards along with mechanisms for enforcing them. Indeed, a recent feature of these trade agreements is the inclusion of social clauses. The Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR)3 did not remain at the fringes of this process. Even if the founding treaty (1991 Treaty of Asuncion) did not include any provisions on labour or environmental rights, the subsequent developments that occurred in MERCOSUR in the 1990s brought about a recognition of these rights.

As a matter of fact, it must be said that these improvements in terms of the MERCOSUR legal and institutional system were (and still are) closely linked to the evolution of economic integration. In other words, the achievements of MERCOSUR depend to some extent upon the deepening of economic integration processes. As these processes evolved, MERCOSUR authorities attempted to adjust to different circumstances. Thus, over the past twenty years the legal and institutional architecture has been adapted to the dynamics of a pragmatic and intergovernmental integration process (Olmos Giupponi 2012). In MERCOSUR's institutional set-up, the dispute settlement mechanism, the awards issued by the ad hoc Arbitration Tribunals4 and the Permanent Tribunal of Review, created in 2002, have all contributed to fostering progress.5

In terms of human rights, MERCOSUR has evolved in the direction of recognizing certain rights and, among them, labour and environmental standards. The inclusion of human rights (and in particular labour and environmental rights) was implemented through the adoption of various declarations, treaties and charters in the late 1990s and at the beginning of the 2000s. In recent years, this trend has been confirmed in the form of various awards issued by MERCOSUR arbitration tribunals. Despite this, the protection of social rights in economic integration has received no attention from legal academics. This article aims at filling this gap in the doctrine. Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to analyse the protection of human rights (focusing on environmental and labour rights, the two most significant areas) in the framework of MERCOSUR law, underlying the main aspects of the evolution of this process and the relationships with domestic law (namely, constitutional law). The main argument put forward in the article is that MERCOSUR accommodated the protection of human rights as non-trade issues in its institutional framework, analysing the conflict between the protection of human rights and trade issues at the sub-regional level. Therefore, the article attempts to provide a socio-legal analysis to fill a gap in the literature. In order to give a complete and clear picture of these developments, the paper examines member states' constitutional provisions and the implementation of MERCOSUR labour and environmental standards before national courts.

The article is structured as follows. In the first section, a general overview of the relationship between free trade and human rights (with a focus on labour and environmental rights) in sub-regional integration agreements is presented. The second section looks into the application of MERCOSUR labour and environmental standards by member states' domestic courts, offering a detailed analysis of the respective constitutional provisions. The third section is devoted to examining how environmental rights and human rights have been addressed in MERCOSUR arbitration awards. Finally, the author's conclusions are summarized in the last section.

1. Economic Integration in MERCOSUR: The Interface between Free Trade and the Protection of Human Rights

As in the case of other free trade areas, MERCOSUR agreements did not originally regulate on the recognition of human rights (Olmos Giupponi 2006). The Treaty of Asuncion did not include rules concerning labour rights, environmental rights or any human rights provisions. In fact, MERCOSUR was conceived purely as a process of economic integration. As a whole, the emphasis was put on market integration rather than on the protection of social rights, and fundamental rights were considered to be of secondary importance. MERCOSUR had no competences in the field of human rights.

Towards the end of the 1990s and at the beginning of the 2000s, the ideas of social dimension and social agenda became relevant in the Latin American integration process (Deacon, Yeates and Van Langenhove 2006). Scholars from the Latin American Economic System (SELA, from its Spanish initials), NGOs and unions criticized the regional free trade agreements because of their lack of commitment to address the social side-effects of economic integration (Franco and Di Filippo 1999). Also, other scholars such as Grandi and Bizzozero stressed the need for a greater participation of social actors (Grandi and Bizzozero 1997). Additionally, other commentators underlined the "democratic deficit" of MERCOSUR because of the marginal participation of third sector organizations (Tirado Mejía 1997).

On the one hand, the demand for citizen participation in MERCOSUR increased, with a particular rise in requests on behalf of NGOs and unions (bottom-up process). For instance, universities, unions and third sector organizations have tried to participate in decision-making processes in MERCOSUR since the beginning (Tirado Mejia 1997). In MERCOSUR, "in practice, the participation of civil society is given at two levels: (i) in the relations between public and private actors within each country; and (ii) on the relations between actors of different countries [...] at both levels there are already instances of institutionalization of participation as the Sectoral Commission for MERCOSUR (COMISEC) in Uruguay" (Tirado Mejía 1997, 52). On the other hand, sub-regional integration processes tried to address the regional governance's lack of social meaning and legitimacy by creating bodies for the participation of civil society (top-down process). The creation of the Consultative Economic and Social Forum constitutes an example of this trend. This consultative body was created through the Protocol of Ouro Petro adopted in December 1994, and approved by the Common Market Group in July 1996. The Forum includes the respective National Sections of each of the member countries and representatives of the business sector and workers (Moavro 1997).

Different actions were taken in order to make sub-regional integration processes more "human rights-friendly." Consequently, various human rights declarations and charters relating to the protection of fundamental human rights were adopted. These instruments often recognized human rights in similar terms to those set up in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and Economic and Social Rights. However, within Latin American FTAs, these provisions differ from those of traditional human rights agreements. This is the case because FTA provisions do not establish monitoring bodies and tend to focus on the protection of specific rights which are considered relevant for the integration process.

In this context, labour rights and environmental protection were included as human rights in the sub-regional integration processes. In MERCOSUR, this new model of regionalism was shaped by the developments and obstacles found within MERCOSUR itself in the protection of both labour and environmental rights, as can be seen in the following sub-sections.

a. Labour Rights

Initially, MERCOSUR member states were reluctant to admit the link between trade and labour issues and to decide whether or not the implementation of higher labour standards should be fostered through trade sanctions (Stern 2003). This reluctance was rooted in the main objective of the liberalization of internal trade, which could be distorted by the inclusion of such norms. Therefore, the improvement of labour standards in the integration process was addressed in non-trade fora and instances. Notwithstanding this initial reluctance, MERCOSUR authorities started dealing with international labour standards and labour rights at the sub-regional level from the mid-1990s onwards.

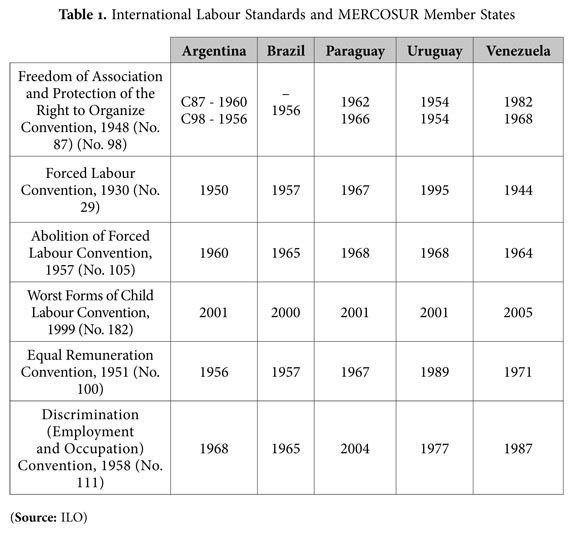

Therefore, the consideration of the linkage between economic integration and labour rights brought about the need to comply with International Labour Organization (ILO) standards and to adopt norms aimed at protecting labour rights at the sub-regional level (Bruni 2004). The ILO and its conventions played a crucial role in the definition of a set of basic or "core" labour standards (see table below). Besides, the improvement of labour standards moved forward through a continuous law-making process, mainly mobilizing worker organizations, companies and NGOs across local, national and regional dimensions.

As some scholars have argued, despite its limitations, MERCOSUR had the potential to evolve into a successful sub-regional model in terms of the protection of labour rights (Schaeffer 2007, 829). This evolution was driven by both governmental and non-governmental initiatives. In the 1990s, the enforcement of labour standards became an important issue on the domestic agenda for most MERCOSUR member states. At the same time, the main social actors in MERCOSUR (unions and NGOs) increasingly began to address the relationship between trade and labour, pushing for the recognition of common labour standards at the sub-regional level. Labour unions played a significant role in this process. Among them, it is worth mentioning the Federation of Labour Unions of the Southern Cone (Coordinadora de Centrales Sindicales del Cono Sur, or CCSCS, from its Spanish initials), which has been working on initiatives to improve labour standards at the sub-regional level.6

In MERCOSUR's institutional set-up, the Working Sub-Group No. 10 on labour issues, employment and social security (WSG No. 10) and the Economic and Social Advisory Forum (FCES, from its Spanish initials), both established in 1994, have contributed to the evolution of MERCOSUR labour standards.7 In particular, the participation of trade unions in the work of these social and labour institutions was relevant in terms of bringing up new elements for the protection of workers and the enforcement of labour standards at the sub-regional level.

At the end of the 1990s, the adoption of a sub-regional charter was included on MERCOSUR'S agenda, and this soon became a crucial issue. These debates on the adoption of a social charter in MERCOSUR could be perceived as a mirroring trend following the European Union's experience with the European social charter. Different actors were involved in these debates, and the CCSCS submitted a final proposal on the approval of a comprehensive Charter of Fundamental Rights. Furthermore, in 1997, member states signed the Multilateral Social Security Agreement (Grugel 2005, 1061).8

As a result of this process, the MERCOSUR Socio-Labour Declaration (Declaración Socio-Laboral) was adopted in 1998. The Socio-Labour Declaration of MERCOSUR (hereinafter referred to as the "Declaration") was approved by the Common Market Council (CMC, from its Spanish initials) within the framework of the Summit of the Heads of State of MERCOSUR, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1998. The Declaration contains a series of workplace principles and rights, and includes, inter alia, the member states' decision to strengthen the progress already achieved in terms of the social dimension of the integration process by adopting a common instrument. Also, through the Declaration MERCOSUR member states showed their commitment to support future and on-going advances in the social field, particularly through the ratification and implementation of the main ILO agreements and other international instruments mentioned in the preamble of the Declaration.

With regard to its legal nature, the Declaration was adopted as a soft law instrument. Consequently, it is not binding for the member states and nothing in its provisions requires compliance, approval or the establishment of a mechanism for internalization and implementation.9 As one can observe, all these labour-related topics that have emerged call for a sub-regional approach that should be adopted by MERCOSUR bodies.10

b. Environmental Rights

No specific provisions on environmental issues were embodied in the Treaty of Asuncion (1991). The only reference made to environmental issues is contained in the preamble of the treaty, which declares that member states seek the accomplishment of a common market, "believing that this objective must be achieved by making optimum use of available resources, preserving the environment [...]."

Despite this absence of specific environmental regulations, shortly after the adoption of the Treaty of Asuncion, MERCOSUR member states issued the Canela Declaration (1992), which enshrined basic international environmental principles further recognized by the Rio Declaration. The participation of third sector organizations concerned with the protection of the environment was very limited. As Tirado Mejia rightly mentioned, initially only the economic sectors and unions were actively involved in the decision-making process (1997). Also on the international level, the Rio Declaration and the recognition of Sustainable Development as a core principle contributed to developing the environmental dimension.

Furthermore, in 1992, a specialized meeting known as the Reunión Especializada de Medio Ambiente (REMA, from its Spanish initials) was established, representing the first institutional mechanism to address environmental issues in MERCOSUR. Among its developments, we can mention the adoption of the "Basic Guidelines for Environmental Policy" in 1994. These guidelines set out a series of principles, minimum objectives and lines of action to be followed by MERCOSUR member states when drawing up their environmental policies. Later on, in 1995, member states adopted the Taranco Declaration on environmental issues. At the same time, environmental authorities asked the GMC to upgrade the institutional status of the REMA in order to create the Working Sub-Group No. 6 Environment (WSG No. 6).

In the 2000s, the main innovation was the 2001 signature of the MERCOSUR Framework Agreement on the Environment (hereinafter referred to as FAE), which constitutes the main legal instrument in MERCOSUR on the matter.11 Among its provisions, the FAE underlines the commitment of member states to cooperate in the implementation of international environmental agreements to which they are party, including the possibility of filing reports when appropriate (Macedo Franca 2010, 225). The FAE also emphasizes the obligation of member states to apply the principles of the 1992 Rio Declaration that are not covered by international agreements. At the sub-regional level, the FAE contemplates the commitment of member states to address environmental problems in the sub-region, stressing the need to cooperate in environmental protection and the preservation of natural resources. Furthermore, Chapter III of the FAE is devoted to Cooperation, regulating it in more detail and proposing a list of activities to be performed by member states in order to enhance the application of environmental norms.12 In a general overview, despite all these relevant provisions, the MERCOSUR Framework Agreement on the Environment does not impose specific obligations on the member states (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2006b).

Additionally, over the past twenty years MERCOSUR has been adopting other environmental regulations such as: the Agreement on the Carriage of Dangerous Goods in MERCOSUR (1994); the Technical Regulation of Maximum Pollutant Emission of Heavy Vehicles (1996); the Code of Conduct for the Import and Release of Exotic Biological Control Agents (2000); the Amendment to the General Plan of Mutual Cooperation and Coordination on Regional Security and Environmental Matters (2000); the Additional Protocol to the Framework Agreement on the Environment of MERCOSUR on Cooperation and Assistance in Environmental Emergencies (2004); the Guidelines for Environmental Management and Cleaner Production (2006); and the Instrument on Promotion and Cooperation Policy on Sustainable Consumption and Production in MERCOSUR (2007).

Up to the present day, there is not a comprehensive study on how member states are applying and implementing these environmental norms adopted within the framework of MERCOSUR. Besides, the above-mentioned Canela and Taranco Declarations merely represent soft law. The evidence provided by the different reports on the application of MERCOSUR law shows that member states are enforcing the norms in different ways, as can be observed in the following section.

2. Application of MERCOSUR Labour and Environmental Standards by Member States' Domestic Courts

In order to better understand how MERCOSUR norms are applied by member states, we shall briefly explain the main features of MERCOSUR law and the different constitutional approaches to it.13 Effective enforcement is a prerequisite for a successful regulatory regime; without enforcement, norms amount to nothing more than words on paper.

The recognition of legislation emanating from MERCOSUR as "community law" has generated a vast amount of academic literature (Olmos Giupponi 2010). The mainstream position emphasizes that the MERCOSUR legal system is still intergovernmental, since member states have not yet given up their sovereign competences (Klein Vieira and Gomes Chiappini 2008). The principal argument in this area underlines the idea that primary law has not endowed MERCOSUR governing bodies with supranational powers. It is true that strictu sensu in the case of MERCOSUR law, the recognition of the typical features of community law in European terms (direct effect and supremacy) is highly controversial.14 Legal scholars agree that the MERCOSUR legal system should currently be considered as a law of integration, which is a specialized category within public international law (Klumpp 2007, 91). The final aim, however, is that MERCOSUR law will eventually evolve into an authentic supranational legal order, in light of the principle of integration as a continuous and progressive process aimed at creating a common market laid down in the Treaty of Asuncion.

Up to the present day, the supremacy of MERCOSUR primary and secondary law has been interpreted in line with each member state's constitutional system (Klein Vieira and Gomes Chiappini 2008). As a result, there are dissimilar solutions in terms of the application of MERCOSUR law according to the different constitutional provisions of MERCOSUR member states, as explained in the sub-section below.

a. Hierarchy of community Law and Human rights Provisions in MERCOSUR Member States' Constitutions

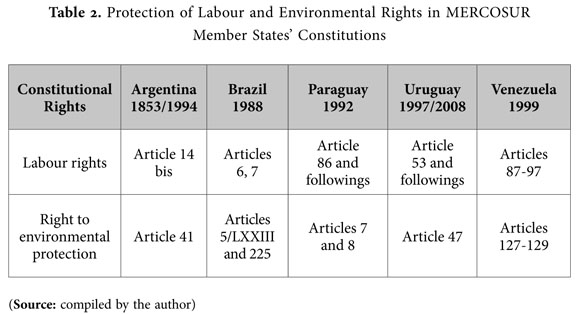

The constitutions of the respective MERCOSUR member states offered different solutions with regard to the relationships between international law and municipal law. It is important to highlight that most of the constitutions were modified in the 1990s and 2000s. In the following paragraphs, the main provisions concerning the application of international law and the protection of human rights (in particular, labour and environmental rights) are examined in greater detail.

Argentina

The 1853, the Argentine Constitution (last amended in 1994) adopted the monist theory of international law, which consequently recognizes the supremacy of legal acts arising from MERCOSUR rules (Perotti 2004). Hence, MERCOSUR regulations should take primacy over others, taking a constitutional or supra-legal form, depending on their nature. The problems arising from the interpretation of (prevalent) MERCOSUR norms may be solved in the light of Article 75, Paragraph 24 of the Constitution. This article sets the predominance of integration treaties and the rules adopted under these treaties.15 Paragraph 22 of the same article establishes the supremacy of the most relevant human rights treaties, which are at the same level as the Constitution and complement the constitutional provisions on safeguarding human rights. Labour rights are protected in Article 14 bis16 whereas the right to environmental protection (introduced by the 1994 reform) is recognized in Article 41.17

Brazil

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution follows the dualism in the recognition and incorporation of international norms into the domestic legal order. This leads (in some cases) to a conflict between domestic legislation and international law. The problem is determined by the need for parliamentary approval of the norms derived from MERCOSUR bodies. Similarly, Article 84, Paragraph 8 of the Brazilian Constitution stipulates that the President may conclude treaties, conventions and international covenants, from the moment they are endorsed by the federal legislature of National Congress.18 This issue raises serious problems in terms of incorporating the rules arising from MERCOSUR. Therefore, MERCOSUR norms in Brazil, once internalized, rank below the constitutional norms and must take the form of ordinary law. It should be mentioned that treaties are incorporated by decree sanctioned by the President of the Republic and may be implemented by regulations.19 The international standards integrated into Brazilian domestic order take the form of a legislative decree issued by the Executive (Presidential Decree). As for other international law norms, internalization is carried out through various forms of administrative acts based on the content of presidential decrees, which, as discussed, are used, for instance, to pass the originating standards and regulations or tariff measures derived from the institutions. The "portarias" (the name given to the administrative acts issued by ministers or secretaries of state and other authorities), are used in many cases to incorporate MERCOSUR norms.20 With regard to human rights, labour rights are protected in Articles 6 and 7, and environmental rights are recognized in Articles 5/LXXIII and 225.21

Paraguay

This member state recognizes the supremacy of international treaties, confirmed by Articles 137 and 141 of the National Constitution of Paraguay (1992).22 With regard to the procedure for the incorporation of MERCOSUR norms, it follows a process of shared competence between the Executive and Legislative branches, but with an emphasis on the consideration of international norms as superior to national norms.23 In this way, after following the legislative procedure established by the Constitution, MERCOSUR norms enter into force within the Paraguayan order as a constitutional or supralegal norm. They may take the form of an act to amend the Constitution or any other form, indicating the special nature of the act in terms of keeping the status of the legislation transposed and applied within the national system. It should be noted that the Constitution of Paraguay states that any MERCOSUR norm, once incorporated by the Decree of the President, will assume the form of law with primacy over national legislation. Labour rights are recognized and protected in Article 86 and the right to environmental protection is addressed in Articles 7 and 8.24

Uruguay

The Constitution of the Republic of Uruguay (1997) also foresees a procedure for the recognition of an international treaty or norm. According to Article 168, Paragraphs 20 and 85.7, the Executive branch may sign agreements or treaties which also require parliamentary ratification.25 There is some uncertainty around the validity of the rule after its adoption by the relevant authorities. The Uruguayan Constitution did not anticipate a solution to this issue as there is no provision for the hierarchical position of international and MERCOSUR norms in the internal legal system. Additionally, Article 239 states that the Constitution represents the supreme law of the legal system, and as such all other laws must be consistent with it. The absence of an explicit provision to cover this area has led to a judicial interpretation which favours the treaty. However, the jurisprudence on the matter has not been harmonized in one sense, which causes even more uncertainty. With regard to the incorporation of the resulting norm, it can take the form of a law or an administrative act, depending on the subject. These may also include executive decrees, ministerial resolutions and ordinances. Labour rights are recognized in Article 53 and following articles and environmental rights are recognized in Article 47.26

Venezuela

As for the Venezuelan constitutional provisions concerning community law, it must be underlined that the preamble of the Venezuelan Constitution (1999) recognizes regional integration as one of its main objectives (Brewer Carias and Kleinheisterkamp 2008). Furthermore, Article 153 foresees that "the Republic shall promote and encourage Latin American and Caribbean integration in the interest of advancing towards the creation of a community of nations, defending the region's economic, social, cultural, political and environmental interests," whereas Article 154 states that treaties concluded by the Republic must be approved by the National Assembly before being ratified by the President. Once ratified, the treaties are incorporated into the internal legal order and have prevalence over national laws (Romero et al. 2003). According to these constitutional provisions (Articles 153-154), scholars agree on recognizing the features of self-execution and direct applicability in the case of norms emanating from the Andean Community (Petit and Caligiuri 2002). Therefore, this also seems to be mutatis mutandi the case of MERCOSUR norms currently applicable in the Venezuelan legal order. As for fundamental rights provisions, Articles 87-97 regulate on labour rights whereas Articles 127-129 contain detailed provisions relating to environmental rights.27

As one can observe, the absence of a real supranational law in MERCOSUR engenders hierarchical differences in terms of the internalization of rules: each member state is free to select the forms it considers most appropriate in order for the norm to enter into force (Olmos Giupponi 2010). This current system has a specific impact on MERCOSUR member states and the application of the different provisions concerning labour rights and environmental protection.

b. The Implementation of MERCOSUR Labour and Environmental Standards by Domestic Courts.

After having analysed the constitutional provisions of member states concerning international law and the protection of human rights, a closer look at the ways in which member states are implementing MERCOSUR labour and environmental standards is in order. The utilization of court processes and the subsequent enforcement of decisions as a case-by-case response to disputes between private parties has contributed to the application of MERCOSUR norms at the national level.

As for labour rights, the Socio Labour Declaration represents an emblematic case in terms of the application of MERCOSUR norms before domestic courts (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2004). Even if the Declaration is not a binding instrument, some domestic courts have applied it on a compulsory basis. For instance, in the ruling of the 6th National Labour Chamber (Argentina), the Declaration was applied as a binding norm in files involving workers' rights (Secretaría del MERCOSUR. 2004, 2006a). In other cases before the same tribunal, the Declaration was deemed as having a higher status than domestic law because it relies on the Treaty of Asuncion and the provisions of Article 75, Paragraph 24 of the Argentine Constitution.

According to the different reports issued by the Secretariat on compliance with MERCOSUR Law, the Socio-Labour Declaration was the main MERCOSUR instrument invoked by different national courts when dealing with work-related disputes (1st and 2nd Report on the application of MERCOSUR norms, 2003 and 2004, respectively). In sum, the Declaration was applied to grant protection to workers on the following matters:

- Right to work and decent conditions of work

- Interpretation of national norms in the light of international human rights instruments, particularly the Pact of San José de Costa Rica and the Socio Labour Declaration

- Job security and dignity, as highlighted and protected in the MERCOSUR Socio Labour Declaration

- Unregistered work as a subtle discrimination in light of Article 1 of the Declaration, in cases where the affected workers were separated from the rest of the workers and marginalized from the social security system

- Freedom of association in its various positive and negative aspects, as reflected in various ILO conventions and protected in the region by the Declaration (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2004).

With regard to the application of MERCOSUR law on the protection of the environment and public health, the rulings of different courts at the national level show how these judicial bodies have been dealing with environmental protection in different ways. As a general feature in terms of the enforcement of international environmental legislation, in Latin America there is a generalized problem concerning the lack of enforcement of environmental legislation (Nolet 1998; INECE 2005). MERCOSUR member states are not the exception to this rule.

Bearing this in mind, there are cases in which internal courts have applied MERCOSUR law to the protection of the environment and public health, such as in the case of Kraft Food Argentina (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2006a).28 There have also been cases regarding the application of the Agreement on the Carriage of Dangerous Goods, for instance, the ruling of the Brazilian Federal Court of the 5th Region (2004).29 In this case, the internal court decided that member states can establish restrictions on the circulation of goods on the basis of the right to protect the environment (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2006a).

In Brazil, the application of MERCOSUR regulations on the importation of retreaded tyres has led to various judgements, both at the regional and federal level, dealing with the protection of the environment.30 The litigation in these cases centred around the restrictions imposed on imports of retreaded tyres based on environmental concerns (for more detail see the section below). In such cases, internal courts applied MERCOSUR regulations, MERCOSUR awards and international norms concerning the protection of the environment (Secretaría del MERCOSUR 2004).

The implementation of MERCOSUR norms does not depict an optimistic scenario. On the one hand, due to the lack of an appropriate system to guarantee compliance with these norms, it is almost impossible to determine their practical effects. On the other hand, the issue of inefficiency is related to a wider web of actors and other political and economic questions which are beyond the scope of this article. Likewise, when considering solutions, there are a range of issues and parties to consider. The populist approaches often bear little relationship to the reality of social problems. This is because knowledge about the implementation of norms is often incomplete. To complicate matters further, the protection of rights and the issue of inequality in the region are closely entangled.

3. Free Trade and the Protection of Constitutional Rights: Human Rights Issues in MERCOSUR Arbitration Awards

The relationship between trade and non-trade issues (mainly human rights) has also been addressed in the MERCOSUR dispute settlement system. With regard to the potential scope for future development in terms of the protection of human rights, the Inter American Court of Human Rights already has competence in this field; the protection of human rights by MERCOSUR institutions could therefore only arise within the scope of MERCOSUR legislation. Up to the present day, the claims based on the protection of human rights submitted in the arbitration procedure only reflect the impact of trade liberalization on specific rights.

In MERCOSUR the compliance with the law of integration is guaranteed through arbitration. The procedure takes place before an ad hoc arbitration tribunal. In 2002, the Olivos Protocol established a Permanent Tribunal of Review (in function since 2004), which is in charge of the appeal and interpretation of the awards issued by the ad hoc tribunals. In general terms, the arbitration procedure concerns the settlement of commercial disputes excluding non-trade issues. Furthermore, the complaint procedure is mainly available to member states. It is extremely difficult for natural and legal persons to participate in the arbitration procedure. As Cárdenas and Tempesta point out:

- [T]he role played by individuals is quite limited because, although they can start the proceedings and will always be heard, they can do nothing if their claims are dismissed. [...] Member states are the ones who have, at all times, control of the proceedings and who, at their discretion, decide whether to resort to the Arbitration Tribunal if the controversy persists. (2001, 345)

In recent years, MERCOSUR arbitration tribunals have analysed environmental matters and human rights issues argued by member states in different disputes. In these cases, the arbitration tribunals solved the disputes from a traditional international economic law perspective: the applicable principle was free trade and environmental and human rights issues were considered as exceptions to that principle (Olmos Giupponi 2011). In some cases, MERCOSUR arbitral tribunals had to ascertain the various aspects involved in the protection of the environment in the context of economic integration. The object of various awards31 was the application of the environmental exception. In other words, different tribunals had to come to a decision about whether the restrictions to free trade, with the objective of protecting the environment, were admissible or not.

In Award No. 1/2005 of the Permanent Tribunal of Review, concerning the dispute on Argentina's ban on the importation of retreaded tyres from Uruguay,32 the Tribunal made clear that:

- This tribunal notes that it is wrong to suggest that there are two principles in conflict or confrontation in the process of integration, as seems to be stated in paragraph 55 of the award under appeal. There is only one principle (free trade) to which some exceptions can be applied (such as, for example, the above-mentioned environmental exception). Furthermore, this tribunal does not agree with the arguments put forward in paragraph 55 (final part) of the award under appeal, according to which the tribunal should apply the application of the above-mentioned confronted principles (free trade and environmental protection) by defining the precedence of one over the other in accordance with the precepts of international law. For this tribunal, the relevant issue is the possibility of invoking the environmental exception under the Mercosur rules and not under international law (sic).

Again, in Award No. 1/2008 of the Permanent Tribunal of Review in the Case "Divergence on the implementation of Award No. 1/05 initiated by the Oriental Republic of Uruguay (Article 30 Olivos Protocol)," the Tribunal recalled:

- There are not two principles in conflict or confrontation [...] There is only one principle (free trade), and [...] some exceptions (such as the aforementioned environmental exception).

In this dispute, Argentina held, on the relationship between environment and trade, that:

- Argentina's law (prohibiting the importation of remoulded tyres) was not only consistent with the laws of MERCOSUR, but also meant a step forward to achieve the welfare of the peoples of the region through the protection of the environment and the health of humans, animals and plants that inhabit its territory. (Section B, page 3.)

The law in question was presented as a preventive measure aimed at avoiding potential harm caused by the use of retreaded tyres as a result of the cost, difficulty and level of risk involved in disposing of these tyres. The Permanent Tribunal of Review determined that the exception based upon environmental issues was not applicable in this case:

- [...] Argentina has presented a long list and reasons related to the problem from the environmental point of view arguing that "the importation of re-manufactured tires (including remoulded) to Argentina, increases the risk for life and health of people, animals and plants." [...] However, the view already expressed by Award 1/2005 does not agree with this assertion by arguing that "the alleged injury at the discretion of the TPR is not serious or irreversible." (n. 17) [...] Adopting a rigid criterion on certain points raised by Argentina would allow the prohibition of importing a large amount of materials in which toxicity, compared with the tyres, could be much higher, such as batteries, cell phones, MP3s, cans, aluminium, tergopor (sic), plastics in general and especially certain species such as the PET material polyethylene (PET), to mention only a few products [...] many of which require between 100 to 1000 years to degrade naturally, in the meantime constituting to a greater or lesser extent an element that involves potential environmental damage. (Laudo No. 1/2008, Point C)

However, the Tribunal of Review underlined that the environmental exceptions to free trade "should be discussed in the future by relevant MERCOSUR bodies" (Laudo No. 1/2008, Point C).

In Award 9/2006 on the dispute between Uruguay and Argentina concerning the interruption of the international bridges between the two states, the ad hoc arbitration tribunal addressed the conflict between free trade/free movement of persons and goods and the principle of the protection of human rights. In its arguments, Uruguay mentioned that the free movement of persons is a principle to be respected and that the roadblocks ignored existing commitments between the parties under international legal instruments. In particular, Uruguay mentioned the International Land Transport Agreement existing between the "countries of the Southern Cone," including other state parties, considered by MERCOSUR instruments as an important goal in terms of advancing integration in the transportation sector. The obstruction of the free movement of passengers and loads provoked by the demonstrations against the installation of the pulp mill affected transport operations under the Convention not only between MERCOSUR member states but also with regard to movements to or from third-country parties to this Agreement. Uruguay also mentioned the rules of the WTO which bind the parties, such as those relating to the treatment of most favoured nation, freedom of movement, and access to markets, among others, which were affected by the measures reported. In conclusion, Uruguay alleged that Argentina had failed to adopt effective measures to end this situation.

Argentina argued that a conflict existed between the right to free expression of thought and assembly, on the one hand, and the right to the free movement of goods, on the other hand. In this case, Argentina emphasized that international human rights standards in force in Argentina have constitutional status, while the integration norms are of legal status. In Argentina's view, human rights concerns may justify a restriction to the exercise of rights under an integration agreement. In order to support its argument, Argentina mentioned the precedent of the Schmidberger case (Case 112/00) decided by the Court of Justice of the European Union, in terms of prioritizing the right to free expression of thought over the right to free movement of goods, which was affected by the blocking of an international motorway by demonstrations. The Tribunal pointed out that:

- In multilateral agreements on trade facilitation, with special reference to the WTO [...] the harmonization of the rights in conflict without considering the commitments made under such agreements is extremely difficult or impossible, because they relied on principles and values accepted by the international community. It is inevitable that the solution of safeguarding interests and values of higher rank should be chosen, because "legal rights" are more valuable objects and could be classified hierarchically in a preferred position. However, the Tribunal considers that [.] this solution would allow some degree of restriction but not the absolute cancellation of the value which is considered minor, in the interests of another to be judged more important. (Laudo Arbitral 9/2006, par. 133)

Furthermore, the Tribunal stated that:

The traffic restriction [...] leads to a restriction on the free movement within the integrated economic space. It can be tolerated provided that the necessary precautions were taken to minimize the inconvenience caused by them and to be adopted in short periods that do not interfere or cause serious injury, which has not been given in this case in which the courts have delayed the solution [...] with serious consequences for both countries. (par. 134)

The Tribunal examined the Argentine position, underlining the fact that the international human rights treaties with positions of constitutional hierarchy recognize the relativity of individual rights before the individual rights of others and the possibility of limiting these on general welfare grounds. The Tribunal concluded that:

- [...] even if according to Argentine law, the right to protest is absolute [.] it must be limited when it affects the rights of others as expressed in art. 29 paragraph 2 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 32 paragraph 2 of the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights and, in particular, regarding freedom of expression, art. 19 paragraphs 2 and 3 and art. 21 of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 19 December 1966, which are an integral part of the Constitution of Argentina since 1994, having been incorporated into art. 75 paragraph 22. (pars. 137-139)

Finally, the Tribunal considered that Argentina had not respected its obligation to limit the demonstrations by adopting appropriate measures. For the very first time, a tribunal in the framework of MERCOSUR referred to human rights standards as limiting to free trade and the free movement of people and goods.

Conclusions

As in other FTAs, MERCOSUR provisions on human rights are narrower in scope and in terms of implementation and enforcement than the countries' respective domestic legal orders. Within MERCOSUR there has been an evolution towards a more protective framework for labour and environmental rights articulated on the basis of the adoption of specific norms (mainly soft law instruments). The Socio Labour Declaration represents a successful example of this trend: domestic courts have applied the Declaration, in certain cases drawing on the supralegal hierarchy in order to protect workers' rights. Furthermore, MERCOSUR environmental standards are also applied to settle disputes in order to safeguard the environment and public health at the domestic level.

With regard to the relationship between trade and human rights at the sub-regional level, MERCOSUR arbitration awards seem to suggest that human rights are penetrating commercial issues. The ad hoc Arbitration Tribunal in the case of Award 9/2006 left open the possibility that in the future human rights protection could represent a limit to free trade.

In a critical appraisal of the enforcement of the different standards, the empirical evidence available up to the present day demonstrates that the implementation of regional and international norms at the national level constitutes the main obstacle faced by member states. Despite the advancements experienced, MERCOSUR legislation is, in most cases, soft law, so the responsibility for compliance rests with each member state. One may wonder, then, what is the main contribution of MERCOSUR to the protection of labour and environmental rights? In my opinion, the different measures taken at the subregional level are contributing to the voluntary enforcement of these standards. A clear example is the lack of enforcement of environmental norms, which present a legal framework for public and private actors (both individuals and corporations) in order to comply with norms dealing with environmental protection both at the domestic and international level.

To conclude, there are still many challenges that MERCOSUR must address. The main one is to increase the protection of labour and environmental rights at the sub-regional level and to further foster the enforcement and compliance of the standards at the domestic level. In this regard, member states (which have primary responsibility for the protection of human rights) often face different obstacles such as the lack of adequate administrative machinery and, ultimately, political willingness.

Comentarios

* This article is based on a paper presented at the workshop "Free Trade Agreements vs. Constitutional Rights" (Bruges, 16th-17th February 2012) organized in the framework of the Jean Monnet Project Constitutional Rights and Free Trade Agreements (CRiFT) programme funded by the European Union.

1 I would like to thank my colleagues who attended the workshop "Free Trade Agreements vs. Constitutional Rights" (16th-17th February 2012), organized by Philippe De Lombaerde and Stephan Kingah at the UNU-CRIS (Bruges), for their useful comments on this paper. All remaining errors are my own.

2 Sub-regional agreements are those in which states have a shared history, cultural links and sense of interdependency. Under this category I include the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR, from its Spanish initials), the Andean Community (CAN, from its Spanish initials), the Central American Integration System (SICA, from its Spanish initials) and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM, from its Spanish initials).

3 By MERCOSUR law I refer to the legal system originating from the Treaty of Asunción (signed in 1991 by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) which created the Southern Cone Common Market (known as MERCOSUR). Venezuela was admitted as a member state in 2006. However, its membership is still pending because the Paraguayan Congress has not yet approved it. Up to the present day, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador are associate states. The main MERCOSUR bodies are: the Common Market Council; the Common Market Group and its various Working Sub-groups; the MERCOSUR Trade Commission; the Parliament of MERCOSUR (since 2007); the Economic and Social Consultative Forum and the Secretariat.

4 During the period 1999-2005, there were ten ad hoc arbitration tribunals constituted under the Brasilia Protocol.

5 The Permanent Tribunal of Review was created by the Olivos Protocol in 2002 and established in 2004.

6 The CCSCS was created in 1986 in Buenos Aires and consists of eight joint trade unions from Argentina (CGT y CTA), Brazil (CGT, CUT, y FS), Chile (CUT), Paraguay (CUT-AyCNT ) and Uruguay (PIT-CNT). Apart from the CCSCS, there are other unions such as Central de Trabajadores Argentinos (CTA); three confederations affiliated to the World Confederation of Labour, and its branch in the region, the Central Latinoamericano de Trabajadores (CLAT); the Centrales Autónomas de Trabajadores (CAT) of Brazil and Chile; and the Central Nacional de Trabajadores (CNT) of Paraguay.

7 The Working Sub-Group 11 created in 1991 is the predecessor of the current WSG No. 10.

8 The MERCOSUR Multilateral Social Security Agreement was signed in December 1997 by MERCOSUR member and associate states.

9 See Secretaría de MERCOSUR (2004).

10 As one of the latest developments in the field, it should be noted that MERCOSUR recently asked to participate in the ILO meetings. See International Labour Office (2010)

11 The Agreement entered into force in June 2004.

12 See Article 6 on the commitment of member states to: a) increase the exchange of information on laws, regulations, procedures, policies and practices as well as its social, cultural, economic and health services, particularly those that affect trade or competitive conditions in the MERCOSUR; c) seek to harmonize environmental legislation, considering the different environmental, social and economic realities of the MERCOSUR countries; f) contribute in order to make that other MERCOSUR forums and agencies address timely relevant environmental aspects; g) promote the adoption of policies, production processes and services that are not degrading to the environment; i) promote the use of economic instruments to support the implementation of policies to promote sustainable development and environmental protection (Acuerdo Marco sobre Medio Ambiente del Mercosur 2001).

13 MERCOSUR legal order consists of primary law (Treaty of Asuncion (1991) and Ouro Preto Protocol (1994)) and secondary law.

14 According to the doctrine of the Court of Justice of the European Union established through its case law in Case 26/62 and Case 6/64. By direct effect we understand that citizens have rights under community law that they can invoke before the national courts. Supremacy means that the norms belonging to community law take prevalence over national norms. Some scholars also distinguish direct applicability as another feature relating to self-executing norms.

15 Article 75. Congress is empowered: To approve treaties of integration which delegate powers and jurisdiction to supranational organizations under reciprocal and equal conditions, and which respect the democratic order and human rights. Te rules derived therefrom have a higher hierarchy than laws. The approval of these treaties with Latin American States shall require the absolute majority of all the members of each House. In the case of treaties with other States, the National Congress, with the absolute majority of the members present of each House, shall declare the advisability of the approval of the treaty which shall only be approved with the vote of the absolute majority of all the members of each House, one hundred and twenty days after said declaration of advisability. The denouncement of the treaties referred to in this subsection shall require the prior approval of the absolute majority of all the members of each House.

16 Article 14bis. Labor in its several forms shall be protected by law, which shall ensure to workers: dignified and equitable working conditions; limited working hours; paid rest and vacations; fair remuneration; minimum vital and adjustable wage; equal pay for equal work; participation in the profits of enterprises, with control of production and collaboration in the management; protection against arbitrary dismissal; stability of the civil servant; free and democratic labor union organizations recognized by the mere registration in a special record. Trade unions are hereby guaranteed: the right to enter into collective labor bargains; to resort to conciliation and arbitration; the right to strike. Union representatives shall have the guarantees necessary for carrying out their union tasks and those related to the stability of their employment. The State shall grant the benefits of social security, which shall be of an integral nature and may not be waived. In particular, the laws shall establish: compulsory social insurance, which shall be in charge of national or provincial entities with financial and economic autonomy, administered by the interested parties with State participation, with no overlapping of contributions; adjustable retirements and pensions; full family protection; protection of homestead; family allowances and access to a worthy housing.

17 Article 41. All inhabitants are entitled to the right to a healthy and balanced environment fit for human development in order that productive activities shall meet present needs without endangering those of future generations; and shall have the duty to preserve it. As a first priority, environmental damage shall bring about the obligation to repair it according to law. The authorities shall provide for the protection of this right, the rational use of natural resources, the preservation of the natural and cultural heritage and of the biological diversity, and shall also provide for environmental information and education. The Nation shall regulate the minimum protection standards, and the provinces those necessary to reinforce them, without altering their local jurisdictions. The entry into the national territory of present or potential dangerous wastes, and of radioactive ones, is forbidden.

18 Article 84.Te President of the Republic shall have the exclusive power to conclude international treaties, conventions and acts, ad referendum of the National Congress.

19 Also, the rules of MERCOSUR are conditional and depend on a complex act resulting from the combination of the competence of Parliament and the President. Te President of the Republic celebrates international acts (Article 84. VIII of the Federal Constitution), while the Congress has the sole qualification to settle definitely on them (Article 49. I). The integration into the regulatory body also requires the enactment, the act that determines the standard of advertising, by executive decree.

20 This is the case of those norms relating to MERCOSUR technical regulations.

21 Article 225. All have the right to an ecologically balanced environment. which is an asset of common use and essential to a healthy quality of life, and both the Government and the community shall have the duty to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.

22 Article 137. The supreme law of the Republic is the Constitution. [The Constitution], the treaties, conventions and international agreements approved and ratified, the laws dictated by the Congress and other juridical provisions of inferior hierarchy, sanctioned in consequence, integrate the positive national law [derecho positivo] in the enounced order of preference [prelación].

23 In practice, the need for the adoption of acts by international law is not defined by the formal quality or the form of consultation that has been assigned, but given its content, is linked to legal nature of the rule.

24 Article 7. Of the Right to a Healthy Environment. Everyone has the right to live in a healthy and ecologically balanced [equilibrado] environment. The preservation, the conservation, the re-composition and the improvement of the environment, as well as its conciliation with the complete [integral] human development, constitute priority objectives of social interest. These purposes orient the legislation and the pertinent governmental policy.

25 Article 168. Te President of the Republic, acting with the respective Minister or Ministers, or with the Council of Ministers, has the following duties: To conclude and sign treaties, the approval of the Legislative Power being necessary for their ratification.

26 Article 53. Labor is under the legal protection of the law. It is the duty of every inhabitant of the Republic, without prejudice to his freedom, to apply his intellectual or physical energies in a manner which will redound to the benefit of the community, which will endeavor to afford him, with preference to citizens, the possibility of earning his livelihood through the development of some economic activity. Article 47. Te protection of the environment is of common interest. Persons should abstain from any act that may cause the serious degradation, destruction or contamination of the environment. Te law shall regulate this disposition and may provide sanctions for transgressors.

27 Chapter IX. Environmental Rights. Article 127: It is the right and duty of each generation to protect and maintain the environment for its own benefit and that of the world of the future. Everyone has the right, individually and collectively, to enjoy a safe, healthy and ecologically balanced life and environment. The State shall protect the environment, biological and genetic diversity, ecological processes, national parks and natural monuments, and other areas of particular ecological importance. The genome of a living being shall not be patentable, and the field shall be regulated by the law relating to the principles of bioethics. It is a fundamental duty of the State, with the active participation of society, to ensure that the populace develops in a pollution-free environment in which air, water, soil, coasts, climate, the ozone layer and living species receive special protection, in accordance with law.

28 See "Kraft Food Argentina s/Recurso de Apelación c/disposición N'016/03 DSA."

29 See, for instance, Tribunal Federal de la 5ta Región, Sala 2 de 31 de agosto de 2004.

30 See, for instance Tribunal Regional de la 2da Región, 2 Sala, Agravo de instrumento N 111.929/RJ.

31 There were three different awards on the same issue ("importation of retreaded tyres"): Arbitration Award 10/2005 (Laudo Arbitral) (in favour of Argentina, overthrown by the Permanent Court of Review); Award No. 1/2005 of the Permanent Court of Review constituted to hear the appeal made by the Eastern Republic of Uruguay against the 25th October 2005 Arbitration Award of the Ad Hoc Tribunal concerning the dispute "Prohibition of the importation of retreaded tyres from Uruguay;" and Award No. 1/2008 of the Permanent Court of Review in the Case No. 1/2008 "Divergence on the implementation of Award No. 1/05 initiated by the Eastern Republic of Uruguay (Article 30, Olivos Protocol)."

32 The Permanent Tribunal of Review addressed the appeal made by the Republic of Uruguay against the 25 October 2005 Arbitration Award of MERCOSUR ad hoc Tribunal.

References

1. Brewer Carias, Alan and Jan Kleinheisterkamp. 2008. Unification of Laws in the Venezuelan Federal System. Paper delivered at the conference: "Uniform Law and Its Impact on National Laws and Possibilities" organized by the International Academy of Comparative Law, the Centro Mexicano de Derecho Uniforme, and the Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas (UNAM). [Online] http://www.allanbrewercarias.com/ [ Links ]

2. Bruni, Jorge. 2004. Los órganos socio-laborales del MERCOSUR: historia y estado actual de la cuestión. International Labour Organization. [Online] http://white.oit.org.pe/spanish/260ameri/oitreg/activid/proyectos/actrav/proyectos/pdf/dec_soclabor.pdf [ Links ]

3. Cárdenas, Emilio and Guillermo Tempesta. 2001. Arbitral Awards under MERCOSUR's Dispute Settlement Mechanism. Journal of International Economic Law 4 (2): 337-366. [ Links ]

4. Deacon, Bob, Nicola Yeates, and Luk Van Langenhove. 2006. Social Dimensions of Regional Integration. A High Level Symposium organized by UNESCO, MERCOSUR, GASPP and UNU-CRIS: Conclusions. UNU-CRIS Occasional Papers (O-2006/13). [Online] http://www.cris.unu.edu/fileadmin/workingpapers/20060607105556.O-2006-13.pdf [ Links ]

5. Franco, Rolando and Armando Di Filippo. 1999. Las dimensiones sociales de la integración regional en América Latina. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL. [ Links ]

6. Grandi, Jorge and Lincoln Bizzozero. 1997. Hacia una sociedad civil del MERCOSUR. Viejos y nuevos actores en el tejido subregional. Inter-American Development Bank. [Online] http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/integracion_comercio/e_INTAL_IYC_03_1997_Grandi-Bizzozero.pdf [ Links ]

7. Grugel, Jean. 2005. Citizenship and Governance in MERCOSUR: Arguments for a Social Agenda. Third World Quarterly 26 (7): 1061-1076. [ Links ]

8. Klumpp, Marianne. 2007. La efectividad del sistema jurídico del Mercosur. In MERCOSUL - MERCOSUR: estudos em Homenagem a Fernando Henrique Cardoso, ed. Maristela Basso, 53-96. São Paulo: Editorial Atlas. [ Links ]

9. Klein Vieira, Luciane and Carolina Gomes Chiappini. 2008. Análise do sistema de aplicação da normas emanadas dos orgãos do Mercosul nos ordenamentos jurídicos internos dos Estados partes. Centro Argentino de Estudios Internacionales. [Online] http://www.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2008/01597.pdf [ Links ]

10. International Labour Office. 2010. Request by an international organization, MERCOSUR, wishing to be invited to ILO meetings. GB.307/Inf.4. 307th Session, Geneve. [Online] http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_124389.pdf [ Links ]

11. International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement [INECE]. 2005. Pilot Project on Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Indicators in Latin America. [ Links ]

12. Macedo Franca, Alessandra. 2010. MERCOSUR and Environmental Law. In The Law of MERCOSUR, eds. Marcílio Franca Filho, Lucas Lixinsk, and María Belen Olmos Giupponi, 225-240. London: Hart Publishing. [ Links ]

13. Moavro, Horacio. 1997. Un nuevo órgano del Mercosur: el Foro Consultivo Económico-Social. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales. 12. [Online] http://www.iri.edu.ar/revistas/revista_dvd/revistas/R12/R12-EMOA.html [ Links ]

14. Nolet, Gil. 1998. Environmental Enforcement in Latin America and the Caribbean. INECE, Inter-American Bank. [Online] http://www.inece.org/5thvol2/nolet.pdf [ Links ]

15. Olmos Giupponi, María Belén. 2012. International Law and Sources of Law in MERCOSUR: An Analysis of a Twenty Year Telationship. Leiden Journal of International Law 25 (03): 707-737. [ Links ]

16. Olmos Giupponi, María Belén. 2011. International Economic Law and Sources of Law in MERCOSUR: An Analysis of a Fifteen Year Relationship. Paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Meeting, Montreal. [ Links ]

17. Olmos Giupponi, María Belén. 2010. Sources of Law. In The Law of MERCOSUR, eds. Marcílio Franca Filho, Lucas Lixinsk, and María Belen Olmos Giupponi, 57-71. London: Hart Publishing. [ Links ]

18. Olmos Giupponi, María Belén. 2006. Derechos humanos e integración en América Latina y el Caribe. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch. [ Links ]

19. Perotti, Daniel. 2004. Habilitación constitucional para la integración comunitaria: estudio sobre los Estados del MERCOSUR. Montevideo: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. [ Links ]

20. Petit, Jorge and Eugenio Caligiuri. 2002. La constitución venezolana de 1999: una herramienta eficaz para la integración andina. American Diplomacy Publishers. [Online] http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2002_04-06/ caligiuri_venez/caligiuri_venez.html [ Links ]

21. Romero, Carlos A., María Teresa Romero, and Elsa Cardozo. 2003. La política exterior en las constituciones de 1961 y 1999: una visión comparada de sus principios, procedimientos y temas. Revista Venezolana de Economia y Ciencias Sociales 9 (1): 163-183. [ Links ]

22. Schaeffer, Kristi. 2007. MERCOSUR and Labor Rights: The Comparative Strengths of Sub-Regional Trade Agreements in Developing and Enforcing Labor Standards in Latin American States. Journal of Transnational Law 45 (3): 829-867. [ Links ]

23. Stern, Robert M. 2003. Labor Standards and Trade Agreements. Research Seminar in International Economics. The University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan. Discussion Paper No. 496. [Online] http://www.fordschool.umich.edu/rsie/workingpapers/Papers476-500/r496.pdf [ Links ]

24. Tirado Mejía, Álvaro. 1997. Integración y democracia en América Latina y el Caribe. BID-INTAL. Documento de Divulgación 1. [Online] http://www.plataformademocratica.org/Publicacoes/7038_Cached.pdf [ Links ]

Protocols and Treaties

25. Tratado de Asunción. 1991. Tratado para la constitución de un mercado común entre la República Argentinca, la República Federativa de Brasil, la República del Paraguay y la República Oriental del Uruguay. [ Links ]

26. Protocolo de Ouro Preto. 1994. Protocolo adicional al Tratado de Asunción sobre la estructura institucional del Mercosur. [ Links ]

27. Acuerdo Marco sobre Medio Ambiente del Mercosur. 2001 [ Links ]

28. Protocolo de Olivos para la solución de controversias en el Mercosur. 2002. [ Links ]

Tribunal Arbitral Ad Hoc

29. Laudo Arbitral 10/2005. Laudo dictado por el Tribunal Arbitral constituido para solucionar la controversia surgida entre la República Oriental del Uruguay (en adelante denominada "parte reclamante", "reclamante" o "Uruguay") y la República Argentina (en adelante denominada "parte reclamada", "reclamada" o "Argentina"), que versa sobre la "Prohibición de importación de neumáticos remoldeados", 25 octubre 2005. [ Links ]

30. Laudo Arbitral 9/2006. Laudo del Tribunal Ad Hoc de Mercosur consitutido para entender de la controversia presentada por la República Oriental del Uruguay a la República Argentina sobre "Omisión del Estado Argentino en adoptar medidas apropiadas para prevenir y/o hacer cesar los impedimentos a la libre circulación derivados de los cortes en el territorio argentino de vías de acceso a los puentes internacionales Gral. San Martín y Gral. Artigas que unen a la República Argentina con la República Oriental del Uruguay", 6 de septiembre 2006. [ Links ]

Tribunal Permanente de Revisión

31. Laudo No. 1/2005. Laudo del Tribunal Permanente de Revisión constituido para entender en el recurso de revisión presentado por la República Oriental del Uruguay contra el Laudo Arbitral del Tribunal Arbitral Ad Hoc de fecha 25 de octubre de 2005 en la controversia "Prohibicion de importación de neumáticos remoldeados procedentes del Uruguay", 20 diciembre 2005. [ Links ]

32. Laudo No. 1/2008. Laudo del Tribunal Permanente de Revisión en el asunto No. 1/2008 "Divergencia sobre el cumplimiento del Laudo No. 1/2005 iniciada por la República Oriental del Uruguay (Art. 30, Protocolo de Olivos)", 25 abril 2008. [ Links ]

Other documents

33. Secretaría del MERCOSUR. 2004. Primer informe sobre la aplicación del derecho del MERCOSUR por los tribunales nacionales (2003). Montevideo: Secretaría del MERCOSUR, Fundación Konrad Adenauer, Foro Permanente de Cortes Supremas del Mercosur y Asociados. [Online] http://www.mercosur. int/innovaportal/file/740/1/infome_derecho_mercosur2003.pdf [ Links ]

34. Secretaría del MERCOSUR. 2006a. Segundo informe sobre la aplicación del derecho del MERCOSUR por los tribunales nacionales (2004). Montevideo: Secretaría del MERCOSUR, Fundación Konrad Adenauer. [Online] http:// www.mercosur.int/innovaportal/file/734/1/2infaplicaciondermcs.pdf [ Links ]

35. Secretaría del MERCOSUR. 2006b. Medio ambiente en el MERCOSUR, Montevideo: Secretaría del MERCOSUR, Sector de Asesoría Técnica. [Online] http://www.mercosur.int/innovaportal/file/736/1/medioambienteenel-mercosur.pdf [ Links ]

National Constitutions

36. Constitution of Argentina (1994). [ Links ]

37. Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (1999). [ Links ]

38. Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil (1988). [ Links ]

39. Constitution of Paraguay (1992). [ Links ]

40. Constitution of Uruguay (1997). [ Links ]

Other Sentences

41. Superior Tribunal de Justicia del Chubut, "Kraft Food Argentina S.A. s/Recurso de Apelación c/Disposición No. 016/03 DSA", expediente No. 19.364-K-2003, sentencia No. 6/04. [ Links ]

Court of Justice of the European Union - Judgments and Opinions of the Court

42. Case 26/62. 1963. Van Gend en Loos v Administratie der Belastingen. ECR, 1. [ Links ]

43. Case 6/64. 1964. Costa v E.N.E.L. ECR, 585. [ Links ]

44. Case 112/00. 2003. Schmidberger. ECR, I-05659. [ Links ]