Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.81 Bogotá May/Aug. 2014

The Dual Function of Violence in Civil Wars: The Case of Colombia*

Philippe Dufort**

** Recently completed his PhD in International Relations at the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge (UK). He was an Associate Editor at the Cambridge Review of International Affairs from 2009 to 2013. He is currently a sessional Lecturer at UQÀM (Canada). His general research interests include: Development Studies; Strategic Studies; Critical IR Teories; International Historical Sociology; Identity and Conflict Politics. His latest publication include: "Introduction: Experiences and Knowledge of War." Cambridge Review of International Affairs 26 (4), 2013; and "Droit international, relations sociales de propriété et processus de paix en Colombie: Une réarticulation politico-juridique." Études internationals 39 (1), 2008. E-mail: dufort@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

When considering both the economic and military dimensions of civil war it is clear that the violence of belligerents has the dual instrumental function of extracting resources and increasing control. Recently developed datasets of geo-localized violent events-such as the ACLED or the SCAD database-open new pathways for explaining strategic dynamics within conflicts. This article underlines how this task can be achieved through qualitative analyses of patterns in belligerents' modes of operation and statistical analyses of violent incidents and macro-economic variables.

KEYWORDS

Political economy of civil wars, microdynamics of civil wars, armed actors, warfare, quantitative studies, counter-insurgency

La doble función de la violencia en las guerras civiles: el caso colombiano

RESUMEN

Al considerar la dinámica económica y militar de la guerra civil se aprecia que los actores usan la violencia para cumplir dos propósitos: extraer recursos y aumentar el control. Las bases de datos (eventos violentos geolocalizados) recientemente desarrolladas ofrecen nuevas explicaciones para entender las dinámicas estratégicas de los conflictos. Este artículo muestra cómo esto se puede lograr mediante el análisis cualitativo de los patrones en los "modos beligerantes de operación" y el análisis estadístico de incidentes violentos y variables macroeconómicas.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Economía política de las guerras civiles, microdinámica de guerras civiles, actores armados, conflictos armados, estudios cuantitativos, contrainsurgencia

A dupla função da violência nas guerras civis: o caso colombiano

RESUMO

Ao considerar a dinâmica económica e militar da guerra civil, observase que os atores usam a violência para cumprir dois propósitos: extrair recursos e aumentar o controle. As bases de dados (eventos violentos geolocalizados) recentemente desenvolvidas oferecem novas explicações para entender as dinâmicas estratégicas dos conflitos. Este artigo mostra como isso pode ser atingido mediante a análise qualitativa dos padrões nos "modos beligerantes de operação" e a análise estatística de incidentes violentos e variáveis macroeconómicas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Economia política das guerras civis, microdinâmica de guerras civis, atores armados, conflitos armados, estudos quantitativos, contrainsurgência

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint81.2014.07

Received: April 15, 2013 Accepted: September 20, 2013 Revised: February 28, 2014

Introduction1

While mainstream media portrayals often characterize violence as both irrational and chaotic, political science emphasizes the rational nature of violence. Among the several approaches that take the instrumentality of violence as their focus, quantitative studies are perhaps the most influential. Research projects compiling large datasets on civil war (e.g., Singer, and Small 1994; Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg, and Strand 2002), have used econometric analyses in order to identify the most influential factors in the onset and duration of civil war. Without a doubt, this approach has resulted in heuristic, cross-country comparisons and has provided extremely valuable sources of data. Paradoxically, by focusing on the conflict itself as the unit of analysis, researchers have been restricted in the types of questions they can ask. As Tarrow pointed out, these studies have now "reached a plateau in their capacity to inform or enlighten" (2007, 587). Therefore, studies on conflict should not be limited to the structural determinants of their initiation, duration, and termination, but rather, should also consider internal strategic dynamics in order to better understand the meaning of each variable involved. In spite of their flaws, by identifying the most significant macroeconomic variables, such quantitative studies have nonetheless demonstrated the necessity of bringing the economic feasibility of rebellion back to the forefront of our analyses.

In fact, it appears that conflict dynamics cannot be understood without differentiating the overlapping trends within them. The aggregation of data at a global or national level makes it difficult to distinguish the various dynamics at play. The meaning of a variable in one specific context is often different in another. For example, the reduction in violent incidents can be symptomatic of pacification, control consolidation, or military parity, depending on the context. Thus, qualitatively identifying these general strategic trends within conflict is essential to interpreting statistics. Acknowledging this inherent limitation of a macro-perspective, this article proposes the concept of "mode of operation" in order to study strategic dynamics in civil wars at the intrastate geographic level. This concept, this article argues, allows both strategic and economic determinants to be considered through a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods.

The main implication of considering both the economic and military dimensions of civil wars is to reveal the dual instrumental function of belligerents' violence; any violent act has simultaneous impacts on resource extraction and control attempts. Violence aimed at resource extraction may harm a contender's attempt to increase control and vice versa. This deduction explains why the use of violence is so "tricky" in civil wars. New pathways for explaining strategic dynamics within conflicts are now being contemplated in order to consider violent events though the use of geo-localized data collection (e.g., Raleigh Linke, Hegre, and Karlsen 2010; Hendrix, Salehyan, Case, Linebarger, Stull, and Williams 2010). Using more localized data allows us to identify specific trends in conflict by following the strategies used by armed actors to secure economic resources and to enhance control. This approach calls for quantitatively tracing the constellations of strategic and economic incentives that structure belligerents' behaviours at the local level in civil wars.

This article underlines how this complex task can be achieved, on the one hand, by using qualitative analyses of patterns in belligerents' modes of operation and, on the other hand, statistical analyses of violent incidents and macro-economic variables. Moving between the two methods allows for identifying the main strategic dynamics temporally and spatially and for comparing their manifestations synchronically and diachronically. As the example of the Colombian conflict demonstrates, a qualitative understanding of each belligerent's mode of operation allows for identifying trends in military competition where variable variations have a shared meaning.2

The first part of the article proposes a process based on two mechanisms that explain the interdependence of the economic and military dimensions of civil war through an analysis of belligerents' behaviours. This qualitative analysis is described as a mode of operation, the occurrence of which can be associated with variations in specific forms of violence and economic variables. The second part applies the proposed method to the Colombian case. The paramilitaries' mode of operation will first be qualitatively identified through a socio-historical analysis. This approach allows for chronologically and geographically mapping the development of specific dynamics within conflicts. Those dynamics are understood as the geographic expansion/constriction of the qualitatively-identified modes of operations of the belligerents under study during a defined period of time. The case of Colombia is of special interest as it allows us to better understand the relationship between military control and resource extraction by irregular belligerents since both rebels and insurgents have formed irregular armed groups. As it involves irregular actors on both sides of the war, the Colombian case enables a deeper understanding of the role of violence in civil wars. In other words, this case allows for studying violence as used by both insurgent and counter-insurgent irregular actors.

The first section proposes centring the study of armed conflicts on the dynamic process that qualitatively characterizes the strategic modes of operation linking resource extraction and patterns of violence by belligerents. This approach integrates the economic macro-determinants identified by quantitative macro-models to Kalyvas' multi-level theory of military competition. Literature on conflict has overlooked the specific mechanisms explaining strategic dynamics and their interdependent relationship with resource extraction. In other words, the puzzle here is to conceptualize how the dynamics of resource extraction and military competition are linked. As we shall see, disaggregation is absolutely necessary since only certain resources influence belligerents' strategic behaviour, depending on their specific social alliances involving certain economic sectors.

1. Conceptualizing the Process Linking Economic and Military Behaviours

A multi-level understanding of military and economic interdependence is more complex than a simple, unidirectional analysis of insurgents' finances. Defining the process that allows us to qualitatively define the interdependence of these two dimensions represents the key theoretical puzzle of this article. Building on Kalyvas' theory, the process that links the military and economic dimensions of civil war is conceptualized as two connected mechanisms. The first mechanism is the well-developed conception of military control as developed by Kalyvas. The second mechanism, extraction, highlights the role of military resources in allowing resource appropriation. In order to integrate this last mechanism into Kalyvas' theory of irregular warfare, his concept of alliance will be revisited.3 When putting the two proposed mechanisms together, the result is a dynamic process that links the economic and military dimensions of civil war-that is, a standardized approach to qualitatively defining belligerents' modes of operation.

Military competition during civil war is influenced by more than the military capacity of the state. Belligerents' behaviour is structured by local imperatives that are related to different levels of control. Following Kalyvas' model of the joint production of violence, control is established and consolidated using scarce military resources that must be used in the most effective way. In other words, belligerents use these military resources to produce violence and gain civilians' "collaboration via deterrence" (Kalyvas 2006, 142) in order to provoke a shift in the balance of control.

The combination of micro and macro approaches described in Kalyvas' theory allows for a conceptualization of the relationship between belligerents and their context while avoiding the overly simplistic explanations that characterize political economy perspectives on civil war (e.g., rebellion as business arguments). For this purpose, Kalyvas' theory is highly relevant since it theorizes the complex strategic dynamics inherent to variations of levels of control in civil war. However, Kalyvas relegates all economic influence on strategic behaviour to conjunctures. Consequently, economic influences are only considered on a case-by-case basis. This is highly problematic since their systematic influence on conflict has been verified by research on the political economy of civil war.

At the core of this theoretical exercise lies the concept of alliance. Kalyvas (2006, 382) inductively suggests this concept as a complementary mechanism that structures the relationship between belligerents and civilians (meso level):

- Alliance entails a process of convergence of interests via a transaction between supralocal and local actors, whereby the former supply the latter with external muscle, thus allowing them to win decisive advantage over local rivals; in exchange, supralocal actors are able to tap into local networks and generate mobilization. A great deal of action in civil war is, therefore, simultaneously decentralized and linked to the wider conflict. Thus civil war is (also) a process that connects the collective actors' quest for power and the local actors' quest for local advantage. Put otherwise, violence can also be a selective benefit that produces local mobilisation via alliance. (383)

Here, alliance is understood in a more precise manner in order to emphasize alliances based only on economic grounds. The local cleavages considered are therefore limited to socio-economic antagonisms. It is in this context of local civilian economic feuds that belligerents intervene to access resources. As a necessary condition for the establishment and continuation of such local alliances, the armed organization needs a minimum degree of control over the area. Indeed, as mentioned in the previous citation, the alliance is based on a belligerent's capacity to provide "external muscle" in order to give his allies an economic asymmetric advantage.4 Violence is therefore shaped by the nature of the alliance, not only by control. Land-based conflicts offer typical examples of this mechanism, where an armed group allies itself with large landowners and agro-industrials while another sides with small-scale peasantry. Consequently, the two groups have access to different resources depending on their position within social institutions and local power relations.

2. The Process Linking the Economic and Military Dimensions of Civil War: A Synthesis

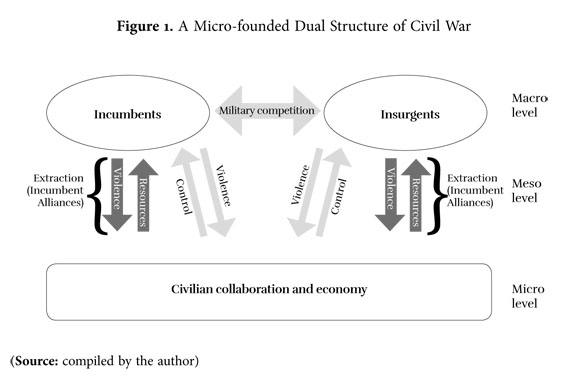

The concept of alliance is presented by Kalyvas as a complementary mechanism at the meso level of his multi-level approach (see Figure 1). Its inclusion makes it possible to connect the complex microstrategic interactions of armed actors during civil war (structured through the joint production of violence) to their economic context by considering extraction as a form of alliance between civilians and belligerents.5

All things considered, integrating extraction as a complementary mechanism into Kalyvas' theory expands his explanatory scope in two ways. First and foremost, it explains the interdependence of the economic and military dimensions of civil war. Military competition at the macro-level can be partially explained as a function of belligerents' financial capacity. Secondly, it explains how belligerents' behaviour is simultaneously structured by both economic and military imperatives while producing violence towards civilians. On this basis, complex strategic behaviour can be studied by isolating patterns in sets of economic and violence-related data. The data on the macro-variables and the statistics on violence can therefore be disaggregated, related, and interpreted according to a better understanding of the internal mechanisms of conflict.

Understanding belligerents' agency during civil war must not be limited to the results from only one level of analysis; for a full picture, agency must be analysed from various levels. Kalyvas defines agency in the encounter of the micro and macro dynamics of civil war in terms of military competition for control. Similarly, the theoretical "structure" is neither associated with the micro nor macro level. Rather, it is conceptualized within this multi-level articulation. The integration of an alternative mechanism into Kalyvas' framework does not create problems regarding the level of analysis since both mechanisms operate complementarily at the meso level (linking civilians and belligerents). However, a significant tension results from the duplication of the considered dimensions.

The main implication of simultaneously considering the economic and military dimensions of civil war is that the violence of belligerents has the dual instrumental function of extracting resources and increasing control (see Figure 1). While producing instrumental violence, belligerents' behaviour is structured by the two mechanisms, which operate at the meso level. Any violent act has simultaneous impacts on both mechanisms. This deduction explains why the use of violence is so "tricky" in civil war, as violence used for extractive purpose can have a synergic or backlash effect on control. Material structure is therefore contextualized simultaneously in the economic and military dimensions. Economic structural imperatives affect the extractive behaviour of belligerents through the mechanism of extraction. Military structural imperatives affect the behaviour of belligerents in competition for control through the mechanism of control variation. In this case, the structural imperatives of extraction and control maximization are present at the micro level (the economic antagonism and collaboration of civilians) and the macro level (macroeconomic variables and military competition), and are articulated at the meso level (extraction and control variation mechanisms). Correspondingly, it is possible to propose a conceptualization of agency as simultaneously embedded in economic and military structural imperatives-or more succinctly, as modes of operation.

3. Strategic Dynamics, Agency and Empirical Observation: The Concept of Mode of Operation

The interdependence of the economic and military dimensions of civil war can be understood from the perspective of belligerents in terms of financial and military viability. It can also be analysed from a macro perspective in terms of transformations in economic and military contexts. These two perspectives represent two sides of the same coin. However, the qualitative understanding of belligerents' alliances remains the first step in understanding the dynamics of a conflict. The empirical study of its microdynamics reveals the meaning of large-scale variations in statistical data related to violence and pertinent economic sectors. Therefore, microanalysis shall precede the contextual analysis in order to explain the relevant relationships between the macro-variables.

Structured within the micro-mechanisms identified, belligerents develop certain regularities in their behaviour while seeking to attain, sustain, and expand their economic and military capacity. In this strict sense, I propose defining and observing those regularities specific to a belligerent's strategy as constituting a mode of operation. Therefore, a mode of operation is defined as a constant pattern in a belligerent's practices aimed at increasing military and economic capability.

The recurring practices that constitute a mode of operation occur at the confluence of Kalyvas' micro and macro levels of analysis. These recurring practices of a belligerent seeking to increase its financial and military capability are structured through the imperatives of two mechanisms: extraction and control variation. Therefore, the concept of mode of operation represents a constant strategic pattern in belligerents' behaviour when using violence to increase its military and financial capability. As such, the use of violence is structured simultaneously by the imperatives of control variation and extraction. Moreover, a belligerent's capacity to adjust and adapt its mode of operation (notably by adapting its alliances) in function of the changing macroeconomic context explains most of its efficacy in sustaining and expanding its financial capability. Its resulting military resources will thereafter determine its potential gains in terms of control.

The soundness of this concept is not merely theoretical. It makes it possible not only to observe micro-patterns in belligerents' behaviour when interacting with civilians, but also to trace manifestations of these microdynam-ics at the macro-level. Indeed, military and economic capabilities are difficult to quantify in many conflicts.6 Studying the actors based on their recurring practices at the micro-level (i.e., qualitatively defined alliances and the specific forms of violence involved) represents a viable alternative.7 When these recurring practices are applied to a large scale, their related manifestations can be observed at the macro-level. The intensity of military competition for control as exercised by a specific actor can be observed empirically in the specific manifestations of violence they use that are comprised within statistics on violent incidents (e.g., statistics of massacres in the case of Colombian paramilitaries). The nature of the extraction mechanism is qualitatively described as alliances with specific socioeconomic groups and involves specific sectors of the economy. Therefore, variations in extraction opportunities for a specific form of alliance (e.g., agro-producers as long-term allies of Colombian paramilitaries) can be empirically observed through specific economic variables (e.g., agribusiness sectoral data or land concentration).

Testable implications of this conceptualization of agency in irregular warfare can be identified. Strategic trends are composed of the expansion of a specific mode of operation. These modes of operation can be observed diachronically and geographically by correlated variations between allied socio-economic sectors and specific forms of violence. Therefore, the empirical observation of macro-variables should be carried out on the basis of an understanding of the micro-dynamics that cause their variation.

In conclusion, a specific mode of operation is empirically observed through the recurring practices aiming at increasing financial and military capability. The manifestations of a mode of operation are observed through the alliances of an armed actor with socio-economic groups allowing resource extraction and through the form of violence used to secure control. The following example, using qualitative research along with disaggregated data available on Colombia, demonstrates how this method can be applied.

Most studies on the relationship between armed actors and economic niches in irregular wars have concentrated their attention on guerrillas. The work of Echandia Castilla (2006) is especially valuable in this regard as it clearly identifies patterns in the Colombian guerrillas' mode of operation. Castilla identifies the specific types of violent events that are associated with the guerrillas' way of extracting economic resources. Using socio-economic and violence indicators to follow the guerrillas' territorial expansion between 1986 and 2006, his work clearly demonstrates how their geographical expansion correlates with socioeconomic macro-variables corresponding with the economic niches they occupy. Although his work indirectly illustrates the potential of the concept of mode of operation, Castilla never formalized such an approach.

The following section aims at expanding Castilla's general approach to paramilitary groups in order to clearly operationalize a mixed method for studying economic and strategic dynamics through the concept of mode of operation. Colombian paramilitaries were created as natural competitors to the guerrillas as they aimed to take control of the economic niches that allow insurgents to thrive. The case of Colombia is therefore especially interesting for the study of belligerents' modes of operation since both insurgents and counter-insurgents use irregular forms of warfare involving economic extraction from the civilian population. Through this case study, the next section demonstrates how an analysis centred on belligerents' modes of operation allows us to map their progression by a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods and to identify the specific meaning of fluctuations in macro-level variables.

4. Mode of Operation: An Application Using Disaggregated Data

Colombia has suffered the consequences of war for more than sixty years. Since its emergence, the Colombian conflict has been influenced by the changing context of world politics: political liberalism, the Cold War, globalization, the war on drugs, and the more recent war on terrorism. Instead of vanishing, however, as have most other conflicts, the local dynamics have adapted.

Scholars have put forth a number of arguments explaining this long-lasting conflict. Some argue that geography impedes the state from penetrating remote regions, others see Colombians as characterized by a culture of violence, while still others maintain that the objective material conditions of poverty and exclusion are behind the Colombian rebellion (see Red de Estudios de Espacio y Territorio 2004). In order to fully understand the persistence of violence in Colombia, different perspectives (psychology, economics, sociology, etc.) and levels of analyses (individual, local, national, and even global) need to be employed. However, the sin qua non condition of its longevity is the persistence of a viable, armed challenger to the state. Without this, no contention can take the form of civil war. It seems that Colombia has maintained the exceptional material circumstances that allow insurgency to emerge and last. The Colombian conflict has lasted longer than others because both the state and its challengers have been able to access the enormous resources needed to finance sixty years of protracted warfare.

The concept of mode of operation-presented in the previous section of the article as two interdependent mechanisms-will serve to outline and locate the evolution of the most important strategic trend caused by paramilitaries in the Colombian conflict during the 1990s. The strategy at the origin of this trend allowed paramilitaries to maintain their financial viability but also to drastically expand counterinsurgent control. To understand this specific strategic dynamic, this section first qualitatively identifies the paramilitary mode of operation-that is, the specific arrangement of the relationship between paramilitaries' extraction practices and military control. This will allow us to interpret the dynamics underlying macro-economic variations and national variations in violence. As such, the following section exemplifies how a qualitative analysis of strategic dynamics-as mode of operation-allows for more prudent interpretations of aggregated data.

The Colombian conflict clearly does not follow the linear evolution of revolutionary warfare as theorized by Ernesto Guevara (2006 [1961]). In fact, since the appearance of the leftist guerrillas in the 1960s, the confrontation has undergone "successive strategic ruptures that originate in changes in the modus operandi of its protagonists" (Echandia Castilla 2006, 13). An approach exclusively considering macro-variables or micro-dynamics cannot perceive these general trends. Consequently, such analyses of the Colombian conflict data remain extremely thin and contribute few convincing explanations.

First, it is necessary to understand how violence in Colombia was shaped by the unequal distribution of land even before 1964, when what is believed to be today's oldest revolutionary guerrillas appeared: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the National Liberation Army (respectively FARC and ELN, from their Spanish initials). During the period known as "La Violencia" (1946-1953), Colombians fought along the scattered lines of land ownership. Large local landowners mobilized their tenants and fought each other, divided along the lines of the central bipartist cleavage of the liberal and conservative parties (Medina Gallego 2001). During this confrontation, some peasant factions also fought with the liberals but with a more radical agenda. They opposed the very existence of the hacienda (large estate) system and decried the unequal distribution of land (Kalmanovitz 1994).8 Put simply, the hacienda system was the main connection between national and local cleavages during the Colombian "Violencia" period.

The contemporary conflict stems from this history. Its dynamics are entrenched in the pre-capitalist hacienda, a form of rural power that has never been truly reformed. From the mid-1980s onwards, increased levels of global trade accelerated the introduction of agribusiness and narcotraffic into this previously fixed context. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the Colombian rural economy was marked by rapid transformation, where continuity and change were deeply intertwined. Any attempt to reduce the history of the Colombian conflict to a simple and elegant logic would therefore be misleading.

During the 1980s and 1990s, increased international trade and structural adjustment policies, along with the emerging narcotics traffic, led to significant transformations in Colombia's rural economy. As narcotraffic surpluses grew rapidly during the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, narcotics dealers/traffickers/producers increasingly bought land as a way of cleaning narco-dollars (Hylton 2006; Echandia Castilla 1997). The general trend of land concentration indeed has its economic roots in the narcotics sector of the economy, which in turn shaped the dual function of violence in this specific context. The development of the narcotics industry was not a marginal economic trend; in 1994, cocaine exports represented 8 to 9% of Colombia's GDP, making it a significant form of revenue for the country (Clawson and Lee 1998, 25). The dynamics of paramilitary expansion in the 1990s was strongly dependent on the narcotics trade and money laundering, as narcotics traffickers funded paramilitary groups. The growth of the narcotics sector of the economy in Colombia is indeed a central macro-determinant of the expansion of paramilitarism.

Along with the local feuds that stemmed from land concentration and the enlargement of the agricultural frontier, the Colombian rural economy experienced another fundamental change:

- [...] it is possible to appreciate the double dimension of narcotraffic in the farming sector [...]. On the one hand, the use of violence protected a process of "agrarian counter-reform" that obligated the peasant to sell or to abandon his or her land; on the other hand, a rapid modernizing process was introduced due to the adoption of new technologies that determined the transformation of traditional large estates into companies in need of machines and qualified workers for the handling of modern technologies. (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and Department of National Planification 1991, as reported in Echandia Castilla 2006, 33-34)

The emerging large landowners were connected to the money laundering that stemmed from narcotrafficking (Hylton 2006; Reyes Posada 1997). Therefore, contrary to the experience of traditional large estates, they had high levels of liquidity. In this context, what is striking about the Colombian economic liberalization of the 1990s is that investment in modern agriculture was largely introduced by narcotraffickers (Richani 2002).

Once again in the history of Colombia, land concentration antagonized the small peasantry and large estates. Paramilitary violence was used systematically as an "external muscle" to settle local feuds to the advantage of agro-producers. An analysis of the alliances among narcotraffickers, paramilitaries, and agro-producers shows how increasing investment opportunities in the agricultural sector triggered the concentration of land in Colombia. From a macro-analytical perspective, these micro dynamics resulted in the general trend of increasing land concentration: an agrarian counter-reform (Jaramillo 2002). This general economic trend illustrates how violence has a dual function in civil war. The violence used by paramilitaries not only provoked the guerrillas to retreat, it simultaneously transformed the economic context.

Through this process, paramilitary groups, agro-producers, and narcotraffickers became more intrinsically interconnected. After the fall of the big Cartels of Medellin and Cali, in many instances the paramilitary regional strongman was also the head of the traffic networks (e.g., Don Berna, commander of the "Nutibara Bloc" and a preeminent figure in the drug-underworld of Medellin). The fortunes gained from the narcotics trade were legalized through land purchases and investment in modern agro-business. The paramilitaries therefore positioned themselves as a nodal point in this counterinsurgent alliance network.

Colombia's rural integration into the global economy has been mediated through the expansion of the paramilitaries' mode of operation. At the national level, the dual function of this pattern of violence resulted in land concentration and counterinsurgent control consolidation. Without a doubt, globalization and warfare have been closely interacting through this process. In order to better understand this mode of operation, a socio-historical perspective allows us to identify the forms of violence used and the socioeconomic alliances involved.

a. The Paramilitary Mechanism of Military control

The first contemporary Colombian paramilitary group (known as Death to kidnappers or MAS, from its Spanish initials) appeared in 1982 in Puerto Boyacá. Its strategy of irregular counterinsurgency differs from strategies previously used, which were based on regular large-scale military operations. MAS aims to dry the fish out of the water-to paraphrase Mao Zedong's famous axiom. That is to say that its aim is not limited to direct military competition, but is also focused on cutting off the guerrillas' access to civilians, thereby impeding extraction from the civilian economy. In the years following MAS' emergence, its operating mode would serve as a model for its expansion into other regions.

The military component of this emerging mode of operation appeared capable of destabilizing the guerrillas' control over the territory of Puerto Boyacá. To evaluate the first mechanism considered (military control) we must first outline the techniques employed by paramilitaries to subjugate the local population. All social sectors suspected of having a potential connection with socialist, communist and insurgent organizations were targeted for homicide:

- The joint operations of the paramilitary group and the National Army centred their attention initially on disarticulating the work and the organizations of the PCC [Colombian Communist Party] and the FARC. To do so, they exerted a brutal repression on peasant and urban populations; in a systematic and selective way they persecuted activists and union leaders, citizens and politicians, peasants and cattle ranchers, and any person that could have, in any form, a relationship with these organizations or that may support them: "they fumigated" the municipality until they had carried out a general cleansing. (Medina Gallego 1990, 175)

Based on this pattern, the waves of paramilitary violence generally forced the guerrillas to retreat from the zone and leave civilians unprotected (Medina Gallego 1990, 397):

- [...] the insistence on selective assassination and massacres, principally committed by paramilitary groups, aimed at impeding the consolidation of enemies' advances, striking at his support networks, informant networks, relatives, and militia. The massacres were indiscriminate. The list of names at hand was often not more than a sophism, although it was on some occasions real. In fact, more important than the interest of eliminating the other actor's support was the interest in demonstrating the incapacity of the other actor to defend the affected population. And, in consequence, to demonstrate that it would be preferable for the population to subject itself to the new actor, which would end up taking control through terror. (Echandia Castilla 2006, 143)

The use of selective or indiscriminate massacres is a distinct military practice of counterinsurgency intent on gaining control (Pécault 2006, 398). Incidents of massacre, however, tend to decrease as paramilitary control consolidates and guerrillas are forced to retreat (Echandia Castilla 2006, 146). The large-scale application of this recurrent pattern of counterinsurgency has caused an explosion of homicides in the affected zones (Medina Gallego 1990; Pécault 2006; Echandia Castilla 2006).

To register the associated form of violent event, a choice must be made between the two main techniques employed by paramilitaries: individual homicides and massacres.9 There is an extremely important sub-registration of violent incidents in Colombia (Echandia Castilla 2006, 34).10 However, trends are constant from one database to another and are, therefore, quite reliable in identifying patterns of violent incidents against civilians (see Banco de Datos de Violencia Politica en Colombia 2005). The pattern of general homicide rates reflects paramilitary action during the period of 1996 to 2004. For example, between 1988 and 1998, of the cases in which the identity of the perpetuator was identified, 24,751 homicides were ascribed to irregular belligerents in the Colombian conflict. The guerrillas were responsible for 3,884 of these homicides, while the main paramilitary organization and other small, private militia were responsible for 20,887 (CCJ 2007).

The violent practices of paramilitaries seem to determine national trends. However, the homicide rates are not the optimal indicator of paramilitary military action. In fact, any increase in the intensity of combat between the Colombian forces and guerrillas influenced local statistics. The systematic use of collective homicides in paramilitary modes of operation offers a more precise alternative. The incidents of massacre are a very specific manifestation of paramilitary military action aimed at increasing control. Since the model of Puerto Boyacá was exported to other regions, national statistics of massacres have increased significantly. The tendencies in massacre statistics are determined by paramilitary actions and do not correspond with the guerrillas' behaviour. A violent event registered as a massacre is an indicator of paramilitary action intended to increase control.

b. The Paramilitary Mechanism for Resource Extraction

Regarding the second mechanism, resource extraction, we now turn to the socio-historical function of paramilitary violence and its relation to the interests of their local sponsors.11 In fact, the first wave of paramilitary expansion responded to specific imperatives related to their old alliance with large local landowners. Initially collecting voluntary contributions from large landowners and businesses, the paramilitaries then standardized this practice and forced all producers to give them significant payments. The paramilitaries of the 1990s extracted as heavily as the guerrillas previously had through forced "contributions." In many instances, cattle ranchers and other producers who initially collaborated to form paramilitary groups to prevent the guerrillas from "over-extracting" taxes ended up paying even more (Medina Gallego 2005). The very same dynamic sectors of the economy which were targeted by the guerrillas' extractive practices became the socio-economic foundations of the paramilitary organizations (Pécault 2006, 397).

On the basis of voluntary financial support and then systematic extortion, paramilitary organizations progressively consolidated their power on a regional level. The groups first became part of a regional federation in northern Colombia: the Peasants' Self-Defence Forces of Córdoba and Urabá (ACCU, from its Spanish initials). Then, at a national conference of self-defence strongmen held on April 18th, 1997, a federation of the most important paramilitary groups was created: the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC, from its Spanish initials). The formalization of a national umbrella group in 1997 indicates the significant increase in the paramilitaries' military capacity. It gave the organization discursive unity and coordination capacity at the national level.

The appearance of paramilitary groups radically changed the financial condition of military competition: irregular counterinsurgent forces started to compete with the guerrillas for extractive opportunities. Paramilitary groups evolved from dependent, locally-rooted militia founded by large local landowners and businesses that were victims of extortion by the guerrillas into a central belligerent force in the conflict. As described above, the initial economic and military viability of local paramilitary groups was made possible by local, voluntary contributions (Medina Gallego 2005). Later, this irregular mode of operation was consolidated and the local militia became centralized in the regions around local strongmen. As for the guerrillas, the paramilitaries used the increasing macroeconomic opportunities of the narcotics trade and trade liberalization to become financially independent from their initial socio-economic bases.

Paramilitaries competed with guerrillas for the very same economic niche, although their alliances with these socio-economic groups were more often collaborative. Up to 1997, they restricted the expansion of the guerrillas in the north of the country. However, after this date, the irregular belligerents competed at the national level and the guerrillas were forced into strategic retreat. In fact, after 1997, the paramilitaries turned to a drastic national offensive strategy and started to expand towards the guerrillas' traditional safe havens. The alliance between paramilitaries and large landowners quickly became part of the conflict dynamic at the national level, as is commonly recognized within specialized qualitative studies (e.g., Duncan 2006; Medina Gallego 1990; Echandia Castilla 2006; Piccoli 2005; Rangel 2005; Richani 2002). In conclusion, the paramilitary mode of operation can be described as follows:

In order to illustrate the plausibility of this argument, the author of this article compiled local data of registered massacres between 1993 and 2000 along with data on the concentration of agri-business. Results indicate that with the agrarian cleavage that has characterized the Colombian conflict since its inception, a strong correlation exists between massacres and agribusiness.

The correlation underlines the heuristic value of such an approach. It relates qualitative understandings of conflict dynamics to quantitative evaluations. In this case it offers an interesting explanation of how massacres are linked to agribusiness through the alliance of paramilitaries and large landowners. The qualitative analysis of paramilitaries' mode of operation allows us to explain how forms of violence and the economic sector are strategically linked.

Building on the new geo-localized datasets identified in the first section of this article, the resource-conflict research agenda could expose the local links between other forms of violence statistics (homicides, forced displacement, rapes, etc.) and economic variation (poverty, agro-industrial production, family farming, PCE, etc.). The meaning of these different variables cannot be interpreted heuristically without a qualitative understanding of each group's mode of operation. Tracing correlations between economic and violence variables not only allows us to corroborate the qualitative analysis, but could also serve to trace the expansion of a belligerent's specific mode of operation in time-space series.

5. Different Readings from the Political Economy of Civil Wars and Micro-dynamics of Civil Wars

Considering the previous analysis, it appears that the microdynamics of civil wars model (Kalyvas 2006) and the political economy of civil wars approach have a more limited grasp on the recent strategic dynamics of the Colombian conflict.

Kalyvas' theorization of violence has already proven its explanatory capacity to link forms of violence (indiscriminate versus selective) with the consolidation of control. However, strongly correlated economic and control variations may expose some inconsistencies. If we consider the violent practices of paramilitaries using Kalyvas' theory, collective indiscriminate violence (mostly indiscriminate massacres) is overused and should not lead to the consolidation of control by counterinsurgents. If Kalyvas' model predicts counterproductive effects in most cases, the Colombian case underlines how the systematic reliance on massacres has been effective in terms of counterinsurgents gaining control.

The recurrent use of massacres by paramilitaries and their success in securing control contradicts Kalyvas' claim that indiscriminate violence tends to be counterproductive. Indeed, in most instances, massacres are indiscriminate and target people by association or randomly (Medina Gallego 2001; Echandia Castilla 2006). The choice to rely on specific forms of violence may need to be understood on the basis of previous descriptions of belligerents' alliances. In the case of paramilitaries, the use of indiscriminate violence does not only destabilize the military control of insurgents, it simultaneously settles local feuds and enhances extraction opportunities:

- Forced displacement of civilian populations has become an integral part of the strategy employed by some paramilitary forces. They employed terror campaigns in some cases to depopulate communities believed to be loyal to leftist guerrillas; in other cases, the paramilitary groups loyal to large economic interests (often including narcotics traffickers) displaced populations so that valuable land and economic assets could then be purchased very cheaply. (US State Department 1998)

Both the macro-cleavage of counterinsurgency and the micro-cleavages related to land conflicts along the agricultural frontier determined the paramilitaries' use of violence.13 The dual function of violence may explain how the indiscriminate violence characterizing the paramilitary mode of operation affects the economic and military contexts and, then, how these effects may favour paramilitary control.

Further analysis of the use of massive indiscriminate violence to provoke the displacement of populations could demonstrate this special feature of the Colombian paramilitaries' mode of operation. Indiscriminate violence is the most likely cause of the displacement of populations and, therefore, could be part of the dynamics generating land concentration. Indeed, narcotraffickers bought more than four million hectares of land in Colombia in 1997 (Reyes Posada 1997).14 During the same period, more than three million people, or around 10% of the Colombian population, were displaced, with population displacement being a phenomenon closely associated with paramilitary practices (CCJ 2007).15 An integrated approach allows us to explain the relationship between economic transformations, variation in military control and violence patterns.

Following an analysis of the dual function of violence and contra Kalyvas (2006), it is imperative to interpret violence-related variables and economic variables as being interdependent. Understanding belligerents' divergent modes of operation allows for a better interpretation of the different meanings for the same aggregated macro-variable.

Indeed, existing intrastate analyses-deprived of a qualitative understanding of belligerents' modes of operation-found very thin explanations of the strategic dynamics involved. Rubio (2002) and Bottia (2003) produced two statistical studies of the Colombian conflict based on the political economy of civil wars approach. These statistical models applied at the intrastate level in Colombia analyse the relationship between violence and economic variables. They identify economic variables, such as mining and land distribution, as being significantly linked to the presence of insurgents.

The first model, produced by Rubio (2002), concludes that the intensity of violence is strongly correlated to the presence of guerrillas and has no significant relationship to "grievance-related variables" (e.g., inequalities or poverty). However, this conclusion remains uncertain if considered in light of Kalyvas' micro model, which explains why the absence of violence in zones of uncontested control cannot be interpreted as the absence of insurgents. In this line of thought, it is correct to affirm that the intensity of violence is strongly correlated with the presence of guerrillas. However, contrary to what Rubio (2002) suggests, it would be erroneous to interpret low homicide rates as the absence of belligerents. The low level of violence can more probably be linked with unchallenged control, as was the case in most regions before the paramilitary surge.16 Since Rubio does not integrate a qualitative analysis of the strategic trends that shape the variations in the main variables, most interpretations remain vague or simply inconclusive.

The second model produced by Bottia (2003) uses logit, probit, and tobit methods to identify the most important factors that determined the FARC's zones of expansion between 1992 and 2000. In line with the integrated analysis previously outlined in this article, her model identifies change in permanent rural revenue as the most significant "greed-related variable" (Bottía 2003, 36). However, the potential for explaining the strategic dynamics at stake are limited because they are based on a binary-dependent variable (the presence or absence of guerrillas). Moreover, the absence of an analytical effort at the micro level does not allow this last author to reach any conclusions on the underlying strategic dynamics explaining this result.

This is not to say that quantitative results using macro-variables are without value. Again, it is only if they are controlled for strategic trends that they can corroborate qualitative analyses of the conflict or allow for generalizations based on micro-dynamic analyses, an avenue opened by geo-localized datasets. As the description of the Colombian conflict considering the strategic and economic dimensions at micro and macro levels have underlined, the macro-dynamics are nothing more than the contingent generalization of effective micro-patterns. It is only by understanding these micro-patterns constituting the paramilitaries' main strategic trends that one can contextualize a shift in data variation and understand their different meanings.

The limitations of the conclusions of quantitative macro-analyses derive from their incapacity to consider these dynamics. As Kalyvas stated, "[p]ay-ing attention to local cleavages is necessary for achieving a closer fit between macrolevel and microlevel theory and interpreting cross-national findings about macrovariables [...]" (2006, 386). The relationship between macro-variables (e.g., agrobusiness, poverty, statistics on violence, etc.) is meaningful when interpreted as the manifestation of local modes of operation (i.e., socio-economic alliances and patterns of violence).

Conclusion

Violent scenarios may appear disorderly and chaotic. However, the material dimensions of conflict are characterized by dynamics that are possible to understand and explain. In order to do so, it is necessary to identify the micro-patterns of each mode of operation and its distinct macro-level manifestations. This complex task can be achieved by using two methods in a complementary way: qualitative analyses of the patterns of strategic microdynamics (i.e., mode of operation), and statistical analyses of violent incidents and macro-economic variables. Although not based on the new geo-localized datasets, the empirical case study demonstrates the soundness of such an argument for future research within the resource-conflict sub-field. The correlation of the indicators of the paramilitary mode of operation illustrates the potential of such an approach. Moving between the two methods could also allow us to temporally and spatially circumscribe the main strategic dynamics and to synchronically and diachronically compare their manifestations. This approach represents a promising orientation to better explain strategic dynamics within conflicts. It identifies trends in military competition that are qualitatively characterized by similar modes of operation and where macrovariables have a shared meaning.

All in all, the conceptualization of agency-as a micro-founded mode of operation operationalizing the dual function of violence in civil wars-could allow for the intrastate empirical study of the strategic dynamics within conflicts and the mapping through time and space of belligerents' main strategic trends. Many other directions and topics could be explored from this perspective. Returning to the Colombian case, it can be postulated that not only did the increasingly globalized market produce extraction opportunities for armed groups, but also that paramilitaries fuelled the global integration of the Colombian agrarian sector through the widespread application of their mode of operation. In this case, paramilitary violence seems to have the dual impact of increasing counter-insurgent control and enhancing an agrarian counter-reform. These interrelations give structure to strategic dynamics and transform the macro-economic context. Considering the dynamic perspective offered by this approach, relating economic and strategic contexts should be a central preoccupation of quantitative studies where relevant disaggregated data are available.

In fact, practitioners have long understood the implications of the dual function of violence in the context of irregular warfare. As in Malaysia under the command of the British High Commissioner Sir Gerald Templer (1952-1954), counterinsurgent violence was used to promote economic sectors particularly hostile to insurgents (e.g., extensive production of palm oil and rubber). Land, violence, and power are linked in many ways. As Herbst (2000) argues in the context of Africa, power and property rights in different regions have different historical foundations and distinct dynamics. It is therefore most probable that alliances between belligerents and civilians are shaped along distinct political, socio-economic and/or cultural peculiarities. The richness of recent microanalyses of these relationships is of enormous value to the study of conflict (e.g., Duncan 2006; Bundervoet 2009; Mamdani 1996). The macro-micro linkage proposed in this article may provide more "thickly" informed quantitative analyses of warfare in different parts of the world while still taking the special features of these societies into account.

Comentarios

* This article is the result of a methodological research seminar organized by Dr Pieter van Houten at the University of Cambridge (UK). The seminar aimed at developing dialogue between different methodological approaches.

1 The author is grateful to Pieter van Houten, Lecturer in Politics at the University of Cambridge, Brian Mabee, Lecturer at the University of London, and Stéphane Roussel, Professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM) for their comments on this article. I am especially in debt to Camilo Echandia Castilla, Professor at the University Externado of Colombia, for his precious collaboration. This research has been conducted with the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

2 In recent studies, a number of authors have approached the role of economic variables in the micro-dynamics of conflicts either by isolating one factor such as unemployment (Shapiro Berman, Callen, and Felter 2011) or poverty (Justino 2009) or through attendant perspectives such as violence against civilians (Metelits 2010) or recruitment practices (Weinstein 2007). As for other authors, who initiated the coeval use of disaggregated economic and violence data, those propositions are not concerned with strategic dynamics per se. During the first stages of the development of the resource-conflict sub-field, this last problematic was not studied in depth due to the hardships of finding usable data. Nevertheless, the appearance of a whole new generation of geo-localized datasets integrating spatial and temporal coordinates opens new opportunities for studying the dynamics of civil war (Cederman and Gleditsch 2009). Buhaug and Gates (2002) initiated the coding of sub-national conflict zones. Buhaug and Red (2006) use a similar perspective. This approach nevertheless "still tends to be too coarse to allow the study of localized accounts of violence" (Korf 2011). A more promising direction for the study of strategic dynamics is the attempt to spatially and temporally code precise events. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED) (Raleigh et al. 2010), the Uppsala Conflict Data Project (Melander and Sundberg 2011), the Militarized Interstate Disputes Location (MIDLOC) dataset (Braithwaite 2010), the Significant Activities (SIGACTS) dataset and the Social Conflict in Africa (SCAD) database (Hendrix et al. 2010) are some of the most promising projects along this line. A theoretically informed approach will be necessary in order to explore these new possibilities. See also Gleditsch and Weidmann (2012) for a review of geo-localized datasets.

3 The second mechanism proposed is based on the argument presented in the last chapter of Kalyvas' The Logic of Violence in Civil War, "Cleavage and agency," (2006, 364-387). Here, he invites further studies to "reintroduce complexity" into his theory through the mechanism of alliance (385). Alliances are conceived here as the micro-founded "missing link" in the second mechanism which explains how local control shapes the extraction of resources.

4 Hirshleifer pointed out this dimension of civil war in the very early days of the debate: "Exchange theory and conflict theory constitute two coequal branches of economic analysis, the first based upon contract and mutual gain, the second upon contest for asymmetric advantage" (1995, 2).

5 Of course, some forms of extraction imply the strong coercion of involved civilians, including extortion, kidnapping, and the protection racket. However, the logic remains the same independent of civilians' willingness to engage in a relationship with belligerents.

6 Therefore, putting the emphasis on the actions of belligerents instead of on their capability represents an interesting empirical orientation that can explain strategic dynamics.

7 This analysis implies identifying qualitatively specific sets of indicators (both violence-related and economic) that capture the specific manifestations of a belligerent's mode of operation when extracting resources (M1) and increasing control (M2).

8 The contemporary guerrillas benefited from the experience of some of these "veterans."

9 A massacre is statistically defined as the assassination of four or more people during one single action (Echandia Castilla 2006, 35).

10 Most analysts agree that only a small proportion of all incidents are reported to the state or observed by NGOs in Colombia. Most incidents are never registered (CCJ 2007; Echandia Castilla 2006).

11 Case studies still have a lot to demonstrate on the topic of civil war. Their "ability to accommodate complex causal relations such as equifinality, complex interactions, and path dependency" (Bennet 2004, 38) should not be overlooked by the quantitative research on conflict. The problem of equifinality is particularly important when studying statistics on violence. A reduction or increase may have very different meanings. This is what makes it such a "tricky" indicator when considered independently from control variation.

12 The local data on massacres have been shared by the Centro de Investigacion y Proyectos Especiales (CIPE) of the Faculty of Finance, Government, and International Relations at the Universidad Externado de Colombia (Colombia). Te data have been originally gathered by the Colombian Government (Presidency of the Republic), the Colombian Police, and the Fundalibertad Institute. The economic data have been gathered from Bogotá in collaboration with the CIPE and other institutions (UNODC and DANE). The economic potential of a department for extraction can be measured by an agglomerate composed of the most relevant economic variables. The sectoral proportion for each department is multiplied by its corresponding proportion in guerrilla finances. The results are then totalled for each department. Te exercise is based on Echandia's (2006, 54) evaluation of guerrilla's finances per sector 1991-1998: a) Petroleum and mining (p): 15%; b) Kidnapping (k): 20%; c) Agribusiness (g): 8%; d) Narcotics (n): 48%; e) Transport and commerce (t): 5%.

- i. As such the agglomerate of sectoral data = p+k+g+n+t. The sources and method used to calculate the departmental value for each sector were as follows:

ii. Petroleum and mining sectors (p) = (Current departmental value of annual production for petroleum and mining in 1999) / (Total Colombian current value for petroleum and mining) (15%) (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística 1999a).

iii. Kidnapping (k) = (Number of kidnappings per department in 1999) / (Total number of kidnappings in Colombia in 1999) (20%) (Centro de Investigacion y Proyectos Especiales [Unpublished Database]).

iv. Agribusiness sector (g) = (Current value of annual production for Agribusiness per department in 1999) / (Total Colombian current value for agribusiness in 1999) (8%) (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, 1999a).

v. Narcotics (n) = (((Departmental production of coca in Kg) (Value of coca exports per Kg) + (Departmental production of amapola in Kg) (Value of amapola exports per Kg))) / (Total value of narcotics exports in Colombia for 1999)) (48%) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2008, 225; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2004, 54, 59).

vi. Transport and commerce (t) = (Current value of annual production for transport and commerce per department in 1999) / (Total current value of terrestrial transport and commerce for Colombia in 1999) (8%) (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadistica 1999b).

13 The national coherence of paramilitarism as a unified force depended on the central cleavage of (counter) insurgency. However, the decentralization of military command into regional blocs was an intrinsic characteristic of paramilitarism. Indeed, paramilitary structures remained highly decentralized and tended to expand in function with the various (and sometimes competing) alliances of its regional strongmen, who had local interests. Local economic opportunities are not limited to land ownership. The confrontation between the Nutibara Bloc and the Metro Bloc in Medellín is a clear case of a struggle between paramilitary organizations for the control of revenues stemming from illicit activities. These alliances with local private interests facilitate a better understanding of why the national paramilitary organization, the AUC, disintegrated in 2003 when the narcotics trade became an issue for demobilization.

14 Other estimates vary from 2.6 to 6.8 million hectares (HREV 2006, 12).

15Colombia has the world's highest number of displaced people (internally and externally) after Somalia.

16 Kalyvas argues that a zone of "[p]arity of control between the actors (zone 3) is likely to produce no selective violence by the armed actors" (2006, 204). However, due to the systematic reliance on indiscriminate violence by paramilitaries and the non-characterization of indiscriminate violence (except massacres) in official statistics, this trend remains hardly distinguishable in Colombia.

References

1. Banco de Datos de Violencia Politica en Colombia. 2005. Deuda con la humanidad: paramilitarismo de estado en Colombia 1988-2003. Bogotá: Noche y Niebla. [ Links ]

2. Bennett, Andrew. 2004. Case Study Methods: Design, Use, and Comparative Advantages. In Models, Numbers, and Cases: Methods for Studying International Relations, eds. Detlev F. Prinz and Yael Wolinsky-Nahmias, 19-55. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

3. Bottia, Martha. 2003. La presencia y expansión municipal de las FARC: es avaricia y contagio, más que ausencia estatal. Documentos CEDE 3. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

4. Braithwaite, Alex. 2010. MIDLOC: Introducing the Militarized Interstate Dispute Location Dataset. Journal of Peace Research 47 (1): 91-98. [ Links ]

5. Buhaug, Halvard, and Gates Scott. 2002. The Geography of Civil War. Journal of Conflict Resolution 39 (4): 417-433. [ Links ]

6. Buhaug, Halvard, and Jan Ketil Rod. 2006. Local Determinants of African Civil Wars, 1970-2001. Political Geography 25 (3): 315-335. [ Links ]

7. Bundervoet, Tom. 2009. Livestock, Land and Political Power: The 1993 Killings in Burundi. Journal of Peace Research 46 (3): 357-376. [ Links ]

8. Cederman, Lars-Erik, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. 2009. Introduction to Special Issue on "Disaggregating Civil War." Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (4): 487-495. [ Links ]

9. Centro de Investigacion y Proyectos Especiales [CIPE]. Massacres and Kidnappings Databases. [Unpublished Database]. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

10. Clawson, Patrick, and Rensselaer W. Lee. 1998. The Andean Cocaine Industry. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

11. Comisión Colombiana de Juristas [CCJ]. 2007. Colombia 2002-2006: situación de derechos humanos y derecho humanitario. Bogotá: Coljuristas. [ Links ]

12. Comisión Colombiana de Juristas [CCJ]. 2005. Violencia sociopolítica y violaciones a los derechos humanos en Colombia: la paramilitarización del Estado. Unpublished research document, Bogotá [ Links ].

13. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE]. 1999a. Cuentas nacionales departamentales. Gobierno de Colombia. [Online] http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&task=category§ionid=33&id=59&Itemid=241. [ Links ]

14. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE]. 1999b. Cuentas Departamentales de Colombia. Gobierno de Colombia. [Online] http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&task=category§ionid=33&id=59&Itemid=241 [ Links ]

15. Duncan, Gustavo. 2006. Los señores de la guerra: de paramilitares, mafiosos y autodefensas en Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Planeta. [ Links ]

16. Echandia Castilla, Camilo. 2006. Dos décadas de escalamiento del conflicto armado en Colombia 1986-2006. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

17. Echandia Castilla, Camilo. 1997. Dimensiones regional del homicidio en Colombia. Coyuntura Social 17: 89-103. [ Links ]

18. Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede, and Nils B. Weidmann. 2012. Richardson in the Information Age: Geographic Information Systems and Spatial Data in International Studies. Annual Review of Political Science 15: 461-481. [ Links ]

19. Gleditsch, Nills P., Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Hâvard Strand. 2002. Armed Conflict 1946-2001: A New Dataset. Journal of Peace Research 39 (5): 615-637. [ Links ]

20. Guevara, Ernesto. 2006 [1961]. Guerrilla Warfare. New York: Ocean Press. [ Links ]

21. Hendrix, Cullen S., Idean Salehyan, Christina Case, Christopher Linebarger, Emily Stull, and Jennifer Williams. 2010. The Social Conflict in Africa Database: New Data and Applications. Working paper. Robert S. Strauss Centre International Security Law, University of Texas. [Online] http://ccaps.strausscenter.org/scad/conflicts [ Links ]

22. Herbst, Jeffrey. 2000. States and Power in Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

23. Hirshleifer, Jack. 1995. Theorizing about Conflict. In Handbook of Defense Economics (V. 1), eds. Keith Hartley and Tood Sandler, 165-189. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [ Links ]

24. Human Rights Everywhere [HREV]. 2006. Le flux de l'huile de palme Colombie - Belgique/Europe: approche sous l'angle des droits humains. Produced for Coordination Belge pour la Colombie, Brussels. [ Links ]

25. Hylton, Forrest. 2006. Evil Hour in Colombia. London and New York: Verso. [ Links ]

26. Jaramillo, Carlos Felipe. 2002. Crisis y transformación de la agricultura colombiana 1990-2000. Bogotá: D'Vinni. [ Links ]

27. Justino, Patricia. 2009. Poverty and Violent Conflict: A Micro-Level Perspective on the Causes and Duration of Warfare. Journal of Peace Research 46 (3): 315-333. [ Links ]

28. Kalmanovitz, Salomón. 1994. Economía y nación: una breve historia de Colombia. Bogotá: Tercer Mundo Editores. [ Links ]

29. Kalyvas, Stathis N. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

30. Korf, Benedikt. 2011. Resources, Violence and the Telluric Geographies of Small Wars. Progress in Human Geography 35 (6): 733-756. [ Links ]

31. Mamdani, Mahmood. 1996. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

32. Medina Gallego, Carlos. 2005. La economia de guerra paramilitar: una aproximación a sus fuentes de financiamiento. Análisis Politico 53: 77-87. [ Links ]

33. Medina Gallego, Carlos. 2001. Violencia y paz en Colombia. Una reflexión sobre el fenómeno parainstitucional en Colombia. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [Online:] http://solcolombia.tripod.com/violpaz.pdf [ Links ]

34. Medina Gallego, Carlos. 1990. Autodefensas, paramilitares y narcotráfico en Colombia: origen, desarrollo y consolidación. El caso de "Puerto Boyacá." Bogotá: Editorial Documentos Periodísticos. [ Links ]

35. Melander, Erik, and Ralph Sundberg. 2011. Climate Change, Environmental Stress, and Violent Conflict: Tests Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset. Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Uppsala University. [ Links ]

36. Metelits, Claire. 2010. Inside Insurgency: Violence, Civilians, and Revolutionary Group Behaviour. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

37. Pécault, Daniel. 2006. Crónica de cuatro décadas de política colombiana. Bogotá: Norma. [ Links ]

38. Piccoli, Guido. 2005. El sistema del pájaro: Colombia, paramilitarismo y conflicto social. Bogotá: Publicaciones ILSA. [ Links ]

39. Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Hâvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. 2010. Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data. Journal of Peace Research 47 (5): 1-10. [ Links ]

40. Rangel, Alfredo. 2005. El poder paramilitar. Bogotá: Fundación Seguridad y Democracia, Planeta. [ Links ]

41. Red de Estudios de Espacio y Territorio. 2004. Dimensiones territoriales de la guerra y la paz. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

42. Reyes Posada, Alejandro. 1997. La compra de tierras por narcotraficantes. Drogas ilícitas en Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Planeta. [ Links ]

43. Richani, Nazih. 2002. Systems of Violence: The Political Economy of War and Peace in Colombia. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

44. Rubio, Mauricio. 2002. Conflicto y finanzas públicas municipales en Colombia. Documentos CEDE 17. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

45. Shapiro, Jacob, Eli Berman, Michael Callen, and Joseph H. Felter. 2011. Do Working Men Rebel? Insurgency and Unemployment in Afghanistan, Iraq and the Philippines. Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (4): 496-528. [ Links ]

46. Singer, J. David, and Melvin Small. 1994. Correlates of War Project: International and Civil War Data, 1816-1992. Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. [ Links ]

47. Tarrow, Sidney. 2007. Inside Insurgencies: Politics and Violence in an Age of Civil War. Perspectives on Politics 5 (3): 587-600. [ Links ]

48. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. 2008. World Drug Report. United Nations. [Online] http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf [ Links ]

49. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. 2004. Informe mundial sobre las drogas. United Nations. [Online] http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/illicit-drugs/index.html [ Links ]

50. U.S. Department of State. 1998. Colombia Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor [Online:] http://www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/1997_hrp_report/colombia.html [ Links ]

51. Weinstein, Jeremy M. 2007. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]