Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.81 Bogotá May/Aug. 2014

The Generalization of Particularized Trust. Paramilitarism and Structures of Trust in Colombia*

Jan Boesten**

** Is a PhD-candidate at the Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia (Canada), working together with Prof. Maxwell A. Cameron. He was a Visiting Researcher at the Universidad de los Andes (Colombia), and a visitor to the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge (UK). Currently, he is a visitor a the Rule of Law Centre at the WZB in Berlin (Germany). His latest publications include Cultural Diplomacy and "The Power of Giving" (Report). Short-study commissioned by th( Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden (with Kurt Huebner and J. Robertson Mcllwain), 2011 and Climate Policies, International Regimes, and Global Trade. A Transatlantic Perspectivt (Report). Institute for European Studies Climate Policies Conference, 2011. E-mail: jboesten@interchange.ubc.ca

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the relation between the politics of state formation and the accompanying appearance of social traps based on the example of Colombia. It shows that egregious exceptions to the rule of law, exemplified by the parapolitica and "false positives" scandals, are themselves a result of "social traps," which are generated by the generalization of particularized trust. The generalization of particularized trust entails the incorporation of a closed trust network in the effort of monopolizing the means of violence against an internal insurgency.

KEYWORDS

Socio-political trust, social capital, social trap, monopolization of violence, Colombia, paramilitarism

La generalización de la confianza particularizada. Paramilitarismo y estructuras de confianza en Colombia

RESUMEN

El artículo examina la relación entre las políticas de formación del Estado y la creación paralela de trampas sociales en el caso colombiano. Se demuestra que las excepciones al "imperio de la ley" (parapolítica y "falsos positivos") son el resultado de "trampas sociales", las cuales son generadas por el proceso de generalización de una confianza particularizada. Este proceso de generalización es la adopción de una red de confianza cerrada, en el esfuerzo de monopolizar los medios de violencia contra la insurgencia interna.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Confianza sociopolítica, capital social, trampa social, monopolización de la violencia, Colombia, paramilitarismo

A generalização da confiança particularizada. Paramilitarismo e estruturas de confiança na colômbia

RESUMO

Este artigo examina a relação entre as políticas de formação do Estado e a criação paralela de armadilhas sociais com base no caso colombiano. Demonstra-se que as exceções ao "império da lei" (parapolítica e "falsos positivos") são o resultado de "armadilhas sociais", as quais são geradas pelo processo de generalização de uma confiança particularizada. Esse processo de generalização é a adoção de uma rede de confiança fechada no esforço de monopolizar os meios de violência contra a insurgência interna.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Confiança sociopolítica, capital social, trapaça social, monopolização da violência, Colômbia, paramilitarismo

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint81.2014.08

Received: 4 de junio de 2013 Accepted: 10 de octubre de 2013 Revised: 14 de febrero de 2014

Introduction1

The Colombian political system is rife with paradox. Colombia is a liberal state with a long history of constitutional rule; yet, it has also displayed immensely high levels of criminal and political violence (See Taylor 2009; Gutiérrez Sanín, Acevedo, and Viatela 2007; Archer and Shugart 1997; Martz 1997; Hartlyn 1989, 1988). Illegal armed actors, paramilitaries and guerrilla groups, and the state's armed forces, continually commit atrocities. Formal and informal institutions, which have evolved over centuries, separate the country into a core and periphery that varies in terms of the quality of governance. The Parapolitica and the "false positives" scandals are the latest evidence of the contradictory characteristics of Colombia's political system; again displaying that formally democratic institutions have been co-opted by illicit social forces.2

Drawing on Max Weber's famous definition of the modern state, Colombia's conundrum and its history of violence are usually explained with reference to the failure of the state to build and maintain a monopoly of violence. The lack of state capacity to radiate power from the center to the periphery of the country is attributed to the lack of external competition (Centento 2002) or the peculiar convulsions of internal politics in the creation of the nation-state in Colombia- particularly the ill-conceived decentralizations and federalizations that took place in the 1860s and then again in the 1980s (Centeno 2002; Sánchez and Mar Palau 2006). In addition, the ubiquity of clientelistic networks is argued to have historically weakened the dominance of the central state by relying on brokerage relationships between different factions within the national territory (Osterling 1989; Archer 1989; Peñate 1998; Gutiérrez and Dávila 2001; Eaton 2006; García Villegas and Revelo Rebolledo 2010).

The contention of this paper is not that these explanations are deficient. Its intention is rather to push the analysis of relations of domination in Colombia further and to invoke the existing trust literature in an effort to better understand the results of the sub-optimal equilibrium between the center and the periphery (Acemoglu, Robinson, and Santos 2010) in relation to the rule of law. The paper will proceed by outlining the latest research on the evolution of statehood in Colombia. This literature suggests that the most important disruption to the evolution of a clear monopoly of violence has been the abundance of clientelistic relationships. While clientelism is a century-old phenomenon, its mode has been transformed in Colombia by the international drug trade, internal fragmentation of the party system, and decentralization of rule into what is termed "armed clientelism." The asymmetric loyalties rooted in the capacity to coerce provide a niche for warlords at the regional level to coexist with the central state and build political projects that increasingly co-opt politicians in formal institutions.

My argument is that symbiotic relations between Señores de la Guerra and politicians (Duncan 2006) not only undermine the predictability and rationalization of domination, but also damage the rule of law by emasculating ideal-type trust relations. Constitutional democracies institutionalize accountability towards rulers through various checks on power. In other words, the ruled distrust their rulers and this distrust comes to be expressed in, and built into, democratic institutions. Inversely, in constitutional democracies rulers trust the ruled by granting private and civic rights. The result is that coercion, which is at the disposal of rulers, is made predictable and non-arbitrary. In authoritarian regimes, the relationship between trust and distrust is reversed because citizens cannot exercise checks on established power, nor are they protected from encroachment on their private and civic rights. The result is that coercion is arbitrary. From these findings in the research on political trust and social capital, this paper builds a hypothesis for the Colombian case.

In Colombia, democratic formal institutions coexist with undemocratic informal institutions at the regional level that results in the unpredictable exercise of coercion by warlords. The rule of law becomes a mere nomenclature, since paramilitary groups trust within the confines of their own group but do not extend that trust outside of it. When equipped with sufficient means of coercion, such groups can undermine the rule of law because it is contingent on embedding coercion in structures of distrust. The equilibrium between formal and informal institutions in Colombia that gave rise to the paramilitary phenomenon indicates that this constitutes a social trap. I call this social trap the generalization of particularized trust.

1. The State and Clientelism in Colombia

Since comparative political science ventured to bring the state back in (Evans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol 1985), its capacity to coerce or coordinate society became the central dependent variable of social science research into the character of the state, its relation to society, and its trajectory on the path to becoming the most dominant organization in politics. Charles Tilly (1985, 1992) was in the vanguard of what is sometimes referred to-somewhat derogatorily-as the "Bellicist School" of state formation. This school placed "the organization of coercion and preparation for war squarely in the middle of the analysis" (Tilly 1992, 14). Others in the same tradition stressed that the state was functionally better equipped to deal with competing political organizations (Spruyt 1994), or could better reduce boundary costs and strengthen the center (Herbst 2000).

Poignantly summarized, Tilly argues that states make war and war makes states. He identified four patterns in European state-making (war-making, state-making, protection, and extraction) that mutually reinforced each other in a virtuous-circle-logic. The fourth component is arguably the most crucial, since extraction involves three risky terrains upon which state and society are brought together: adjudication, distribution and production (1992, 96-7). What is more, when it comes to extraction, the dialectics between state and society have the corollary of rationalizing law and bureaucracy. The processes involved imply that a) the balance between those four tasks affects the organization of the state, and b) popular resistance could result in concessions in the form of rights and institutions. What Tilly at first recognized as implications of the evolution of the nation-state, he later identified as mutually reinforcing mechanisms:

- In the long run, increases in governmental capacity and protected consultation reinforce each other, as state expansion generates resistance, bargaining, and provisional settlements, on one side, while on the other side protected consultation encourages demands for expansion of state intervention, which in turn promote increases in capacity.3 (2004)

The apparent teleology of the argument should not detract from the analytical value of the concepts. The South American context of state formation in the nineteenth century provides the opportunity to test the argument against counterfactual variables. What happens without external competition providing pressure to streamline conscription and raise capital for war? Centeno found that South American states might have acted despotically towards their citizens, but have greatly lagged behind in their capacity to coordinate their societies. This weakness of the state in Latin America coincided with a lack of "total war" with external enemies. Colombia's history fits well with this narrative. Since the people of Gran Colombia did not fight each other over an abstract and nationally coherent cause, violence in nineteenth century Colombia (as in the twentieth century) turned inwards and not outward against external enemies (Centeno 2002, 67). Ideological divisions only existed at the elite level; and, the elites built horizontal alliances with regional power clusters but did not vertically integrate the institutions to build a national project (Valencia Villa 2012 [1987]).

Succinctly stated, the lesson from Tilly and Mann in Colombia then is that the virtuous state-making circle also implies a vicious circle that runs in the opposite direction. Bejarano and Pizarro explain:

- If, as Charles Tilly posited, the primary function of the state is its war-making capability, from which then emanate all its other functions (1985, 1992), the lack of war provides an explanation for why this is the case. According to Tilly, states perform four basic tasks: (1) Through "war making," they eliminate or neutralize their foreign enemies; (2) "state making," in turn, implies the elimination of their rivals within the territory; (3) "protection," relates to the capacity to eliminate or neutralize the enemies of their clients; and finally (4) "extraction" allows them to acquire the resources needed to fulfill the other three tasks (1985, 181). All four activities depend on the capacity of the state to monopolize the concentrated means of coercion. [...] Inversely, we argue, the incapacity to fulfill any one of them tends to weaken all the rest. A state like the Colombian one, incapable of eliminating or neutralizing its rivals within its territory, is neither able to eliminate or neutralize the enemies of its potential clients (the citizens) nor to extract the resources needed in order to perform its basic functions. (2001, 252)

These deficiencies of state functions that Bejarano and Pizarro identified in the early 2000s, when paramilitaries and guerrillas were at the apex of their power, have historical origins. Since the days of Gran Colombia in the 1830s, the Colombian republic has not been able to establish a clear and uncontested monopoly of violence. The patterns of violence certainly changed over time, yet, a distinguishable mode of governance weaved into the fabric of the Andean nation remained surprisingly constant in its defining parameters: the vestment of particularistic interest within a framework of statehood. Extraction remained ineffective because the application of political power by the central government always functioned through a network of friendships among unequal parties (Archer 1989).

Such relations among unequal groups are properly defined as "clientelistic relations," and, while their mode has changed over time, they consistently reappear in the course of Colombia's nation-state history. Peculiarly, they conjoin national interest with residual interests emanating from the regional centers of power. Clientelism has three defining features:

- 1) [T]wo parties unequal in status, wealth, and influence; 2) the formation and maintenance of the relationship depends on reciprocity in the exchange of [non-comparable] goods and services; 3) the development and maintenance of a patron-client relationship rests heavily on face-to-face context between the two parties. (Archer 1989)

Colombia's socio-political history is conventionally separated into three different types of clientelism: traditional clientelism, modern or broker clientelism, and market clientelism. Each of the three was prevalent during a different period and exhibited a distinct configuration of informal and formal institutions. The last ideal type involves what some have referred to as "armed clientelism" (García Villegas and Revelo Rebolledo 2010).

Traditional clientelism evolved in the immediate post-independence period. After victory in the wars of independence, national armies ceased to exist, but local militias persevered and became the power base of regional warlords. Gran Colombia was parceled off between these regional Caudillos, who developed the areas under their control economically and tied the population to their domus. Race fears held the militias together and provided a modicum of social cohesion. When they fought each other over ideological projects in vicious civil wars, the resulting institutions did little to unify the country. Rather, when a victorious faction in a civil war imposed its ideological preferences, this remained largely symbolic. Colombians refer to this type of constitutional politics as "changing everything so nothing changes" (Archer 1989; Valencia Villa 2012). Caudillo and state authority coexisted side by side and, given the absence of external war, they had little incentive or need to expand the provision of security as a public good (Centeno 2002, 239). Just as external competition did not force national unity upon Colombia, neither was democracy an inevitable outcome. Democracy was not pushed upon elites by the masses, but rather developed as a "means for elites to share power among themselves in a way that would avoid infighting" (Robinson 2013).

One unusual feature of Colombia is that socio-political commotions, that in other contexts have resulted in modernization and the integration of previously excluded political groups, occurred here as well (see, for example, Collier and Collier 2002). However, rather than modernizing the system as a whole, these commotions only modernized its subsystems (in this case clientelistic relations), attuning them to new contextual conditions. The country's integration into the global economic system, a phase that in Colombia essentially spanned the first half of the twentieth century, "reformed" patron-client relations, tying previously autonomous single patrons together into clusters, who could then negotiate for political favors. As such, the system could even provide some degree of mobility and augment the poor distributive capacity of a weak state (Gutiérrez Sanín et al. 2007; Archer 1989). Even more surprisingly, the evolution of broker clientelism involved something of a democratic opening. In order to avoid infighting, the two political parties decided on a more representative electoral system that, by undercutting the monopolization of power by a single party, provided each one with a voice and replaced military fronts with electoral coalitions (Mazzuca and Robinson 2009, 288). Even judicial review was a by-product of bipartisan cooperation. Moreover, this process was implemented in 1910 and 1911, making Colombia one of the first countries in the world to subject its legislature to the rule of law.

Nevertheless, the capacity of Colombia's formal institutions to incorporate previously excluded social groups was eventually exhausted because the underlying relations of patronage remained intact. The fate of the Revolución en Marcha in the 1930s and the assassination of left-wing populist Jorge Elicier Gaítan in 1948 signaled that the incorporation of the working classes had failed and that the democratization of Colombia along social democratic lines was also a doomed endeavor (Collier and Collier 2002, 457; Sánchez and Meertens 2001, 13). Violence ensued and, though it was briefly avoided by power-sharing agreements under the National Front, regime crisis became a fundamental and ongoing characteristic of Colombia's political system. Insurgency groups on the left and vigilante groups on the right sprung into existence. In addition, regime illegitimacy paved the way for the illicit narcotics trade to take root in Colombia (Thoumi 1995, 2003). The resources from that trade had extensive ramifications for the political landscape. It enabled groups at the margin of the law to build political capital at a regional level and capture state institutions by running their own candidates and intimidating opponents. As a result, those groups could then siphon off resources transferred from the national state to their own municipalities. This is referred to as "armed clientelism" (Peñate 1998; Eaton 2006).

2. Armed Clientelism, Institutions, and Paramilitarism

When the term "armed clientelism" was coined, Peñate used it to describe the practice of the ELN guerrilla of extracting resources from oil revenues in Arauca (1998). Further research showed it resonates equally well with territories, in which paramilitaries exercised control. Yet, there is one important difference between the guerrilla and paramilitaries that is central to the theoretic considerations of this paper: their relation to the state. Initially not only tolerated but instigated by law, paramilitaries sought to boost their legitimacy by aligning themselves with the state against the insurgency. The ties between the evolving paramilitaries and the state were never fully broken, and their evolution over the last two and a half decades provides an analytical narrative regarding how diverging interests and set preferences between the national and sub-national level not only affect the monopolization of violence, as Acemoglu et al. convincingly show (2010), but also the rule of law. The latter can be explained by the de-institutionalization of political trust structures.

Armed clientelism has its roots in the conflation of drug money and politics that began in the 1980s. While the big cartels, and most notably Pablo Escobar himself (Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón 2005; Duncan 2006), did not view the guerrilla as their natural enemy (after all, they received protection from state prosecution in areas under guerrilla control), traditional landowning elites and cattle ranchers very much did. They were amongst the first to feel the brunt of guerrilla infiltration into ranching territory (Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón 2005). The inability of landowners to pay for the security of their estates and the movement of drug traffickers into the real estate market in order to launder money and gain status brought them together into a heterogeneous interest group (Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón 2005, 44). The state, for its part, was caught in limbo, as it had to fight two wars at once: one against the insurgency and one against the drug trade. The coincidence of the two wars had increasingly contradictory results. The state was fighting the guerrilla on the side of landowners, who were gradually joining forces with actors involved in the illicit narcotics trade. In addition, the illegality of the drug trade meant that armed groups benefitted exponentially from narco-trafficking rents, while the state's relative capacities further contracted in those regions (Bejarano and Pizarro 2001).

While the presence of drug money was increasing in Colombia's economy, its political system was undergoing fundamental reforms that also allowed that money to penetrate Colombian politics. The reforms that took place in the second half of the 1980s and then in the new 1991 Constitution aimed to deepen democracy and assuage the regime crisis. Again, the effects were rather contradictory. One reform, the direct election of mayors, provided armed groups with the opportunity to develop their activities and establish much better terms with those municipal governments than with national institutions. At the same time, the traditional party system became increasingly fragmented, resulting in the emergence of electoral entrepreneurs who ran under the banner of a party in name only (Crisp and Ingall 2002; Gutiérrez Sanín et al. 2007). In reality, they organized their elections autonomously from the national directorate, providing an opportunity for local party strongmen to forge strategic alliances with armed actors (drawing their resources from the drug trade) to garner more votes. Together, decentralization and the de-institutionalization of the two traditional parties provided political opportunity structures that strongly benefited actors with high violence capacities. These actors were particularly able to capitalize on weak institutionalization (Sánchez and Mar Palau, 2006).

The 1990s further cemented the state's peculiar position. On one hand, the big drug cartels were dismantled, but on the other, the drug trade did not disappear, and nor did the self-defense forces on the right. Indeed, these self-defense forces underwent their most systemic expansion during this period. The leading figures of the paramilitary movement in the 1990s, the Castaño brothers, learned their craft in the cartels. After falling out with Escobar they formed functional alliances with the state in order to bring him down in the Pepe organization. Furthermore, while the 1968 law that allowed self-defense forces was repealed in 1989, the state responded to increased guerrilla activity in the early 1990s by largely emulating the law under the new CONVIVIR system (the Spanish acronym for Special vigilance and private security services). When CONVIVIR was dismantled in 1997, the ACCU (Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urabá) continued under the AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia)-seemingly uniting the loose confederation of groups under one umbrella organization. Finally, the demobilization of the AUC under Uribe's Justice and Peace Law did not signal the end of paramilitarism, as evidenced by the upsurge of new "criminal bands" such as the Black Eagles (Ágilas Negras). More crucially, the demobilization of the AUC was preceded by what is now known as parapolitica: pacts of mutual support between heads of the AUC and politicians in Congress. In all of this, paramilitaries stood between legality and illegality. The question, then, is how to interpret this bipolarity.

It is well documented that, out of the mélange of violent actors in Colombia, paramilitaries have been responsible for the vast majority of atrocities.4 A fundamental characteristic of these vigilante groups seems to be the unpredictability of their coercion and their lack of accountability. The reason for this lies in their nature. As the preceding analysis made abundantly clear, paramilitaries can hardly be described as mere banditry groups. Any valuable evaluation must begin by taking into account those aspects of their behavior that go beyond pure rent-seeking. However, it is also important not to go to the other extreme and allude to paramilitaries as a full state within a state (let alone a democratic state). Rather, the relationship between paramilitaries and statehood is an ambiguous one: they are at the same time adversaries, allies, and parasites of the state (Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón 2005, 27).

In light of this ambiguous relation with the state, Duncan defined the paramilitary groups at the height of their power as Señores de la Guerra. These Colombian warlords unite a superior capacity (in comparison with the democratic state) to coerce in certain regions and the ability to extract resources to finance coercive capabilities (from illicit sources) with political-military hegemony. This last factor involves the production and regulation of the social norms that govern the interaction and administration of "justice" in the life of "their groups and citizens" (Duncan 2006, 40-46).5 Their hegemony and administration of justice were not intended as a replacement for the state, but rather as a way to compensate for its absence. The paramilitaries' self-declared claim to legitimacy even goes so far as to suggest that they were acting as fighters for democracy. Yet, the strategy utilized to enforce political hegemony (massacres and selective assassination) is anything but democratic. In areas controlled by the paramilitaries there is little room for contestation and accountability-let alone anything resembling the rule of law.

Paramilitary expansion tells us more still. The paramilitary strategy of refounding the nation and legalizing land grabs through counter-agrarian reform (Lopéz Hernández 2010), in fact runs counter to the state-making logic of Tilly's paradigm of the state as organized crime. In this paradigm, rules are homogenized and rackets turned into taxes. In Colombia, paramilitarism drove a wedge between territorial expansion and policing. As Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón explain with the example of paramilitaries in Puerto Boyacá, in a "system [based on] territorial delegation, each commander [gave] a zone to a subcommander, who has latitude to impose his own rules" (2005, 24). Econometric data from the parapolitica scandal corroborates this evidence. Acemoglu et al. found that a deficient monopoly of violence in "peripheral areas, can be an equilibrium outcome which 'modernization' need not automatically change" (2010, 2). They show that by controlling citizens' voting behavior, paramilitaries can delegate votes to their preferred candidates, reducing "the incentives of the politicians they favor to eliminate them." The result is that "in non-paramilitary areas policies are targeted to citizens while in paramilitary areas they cater to the preferences of paramilitaries," thereby providing citizens in those areas with fewer public goods (2). This suboptimal outcome is locked-in with relative stability, because "paramilitaries deliver votes to politicians with preferences relatively close to theirs, while politicians they helped elect leave them alone" (2).

The contention of this paper is that an accompanying phenomenon to the symbiotic equilibrium between politicians as representatives of the state and non-state armed actors is the prevalence of informal institutions that undermine the effective rule of law. Moreover, this points towards a social trap in which the political trust relations that assuage the potential for violence through embedded negotiations are displaced by those informal institutions. This is what I call the generalization of particularized trust.

3. Politics and the Question of Trust

The issue of trust has appeared repeatedly in academic debates on questions of democracy and the quality of democracy. Most famously, it was included in Robert Putnam's definition of social capital, which, for Putnam, is the fuel that makes a democracy vibrant (1993). Ever since Putnam's famous rendering of social capital as the product of norms, networks, and trust, which results in social cooperation and fosters deeper democratization, the research on social trust has progressed considerably. Most importantly for the purposes of this essay, research has shown that not all forms of trust are beneficial for fostering social goods and democracy. On the contrary, "bad social capital" can function as an impediment to deeper democratization despite formally democratic institutions (Warren 2008). My definition of the Colombian situation as a social trap that constitutes the generalization of particularized trust works off research into the logic and nature of bad social capital. I will proceed by outlining basic definitions of social and political trust and their function within political systems. From there, the essay moves on to identify the paradox of trust in democracies, which suggests that sovereign power cannot be trusted, but that citizens must trust each other in order to make democracy vibrant. Such ideal-type structuration of trust is reversed in autocratic regimes (rulers are trusted, while citizens are not trusted and cannot trust each other), providing the necessary clues to identify the structuration of trust in nominally-democratic regimes with a weak monopolization of violence, such as Colombia. In Colombia, institutionalized distrust, in the form of formal democratic institutions, is displaced at the regional level by undemocratic informal institutions.

When we return to Weber's famous rendition of the modern state as the "human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory," we quickly encounter its relation to trust as a basic social fact (1994, 304). What is important is that it is not solely the capability to monopolize the means of force, but also to make a legitimate claim to those means, that defines the state. This legitimate claim to the monopoly of violence becomes important, because even though the abundance of violence is without a doubt the greatest impediment to the evolution of social trust, it does matter, as I will show below, how this trust is affected by political institutions in society.

Niklas Luhmann posited that the "absence of trust would prevent [humans] even from getting up in the morning. [They] would be prey to a vague sense of dread, to paralyzing fears" (1979, 4). From there, it is not a great leap to see that the monopolization of violence is intrinsically important to the evolution of trust, since coercion in the hands of every individual in the form of violence is certainly the most dangerous or risky element inherent in political situations. Consequently, the monopolization of violence helps generate trust and reduce risk by taking the violence that is potentially in the hands of every individual or group and subduing it to the monopoly of the state. The state thereby converts unpredictable and arbitrary violence into patterned coercion, a pattern that is unquestionably deficient in Colombia.

However, the issue of social trust is not as simple as that, since trust as a fact of social life is entangled in the human condition: in the reality that men and not man populate the earth (Arendt 1958). It is also from this basic fact of human existence that trust becomes functionally important to reduce complexity. To trust someone implies an expectation of a certain type of behavior in the future, while this judgment is made in the present. A person bestowing trust cannot supersede time, but must come to a decision about the future in the present situation: yet, "neither the uncertain future nor even the past can arouse trust since that which has been does not eliminate the possibility of the future discovery of alternative antecedents" (Luhmann 1979, 12).

The situation, though, gets more complicated still as the social dimensions (the first-hand experiences of other people) only increase the world's complexity. As such, the alter-ego (the appearance of other people's first-hand experience in our own consciousness) is a "source of profound insecurity" (Luhmann 1979). This profound insecurity does not diminish with the sophistication of rationalized planning. Rather, rationalized planning entails a projection of the dependencies and contingencies that a decision might bring about and, with that, an increased number of future possibilities. Hence, "indeterminate complexity [...] is actually a consequence of instrumental planning" (1979, 15). Thus, society is reliant on trust, as it is situated between the confidence of what is known and has happened and the contingency of new possibilities. At the same time, however, the contingent nature of these new possibilities carries with it the potential for paralysis.

In order to properly define trust and distinguish it from hope or familiarity, as well as to understand it as a social phenomenon that connects the individual with the multitude, we then need to tie together risk, complexity and the individual decision one takes to cope with that risk. Succinctly stated, on a very basic, individual level, trust "involves a judgment [...], tacit or habitual, to accept vulnerability to the potential ill will of others by granting them discretionary power over some good" (Warren 1999, 311). It is a personal or individual judgment on the behavior of other individuals. In short, it is a "gamble, a risky investment" (Luhmann 1979, 24). However, trust can come with positive and negative externalities, requiring a deeper investigation into its ontology for us to draw intelligible conclusions for the Colombian events and processes outlined above.

Politics, by definition, amplifies risks and foregoes cognitive solutions modeled after past experiences. Political situations are set apart by their conflictual nature or by the fact "that some issue or problem or pressing matter for collective action meets with conflicts of interests or identities" (Warren 1999, 311). Mark Warren juxtaposes this to the apparent automatism implicit in familiar social relations6, arguing that "when social relations become political [.], one or more of the goods of everyday life have become problematic in ways that are not addressed, or no longer addressed, by the relatively automatic coordination of social relationships" (Warren 1999, 312). In addition, not only do traditional means of coordinating social relationships break down, "political uncertainty is never benign. Parties to a conflict bring with them resources (coercive, economic, and symbolic) which heighten the chance of losing" (Warren 1999, 312).

Of course, Carl Schmitt defined the essence of politics as the decisions between friend and foe (2002). However, politics is not as one-sided as this definition suggests. Instead, it retains an ambivalent nature within its confrontational shell; conflicts and uncertainties contain risks and possibilities. Warren, for example, refers to Arendt's principle of natality functioning in the domain of politics. In other words, when situations become fractious-that is, when they cannot be solved by references to established social norms-new possibilities emerge to alter these social norms (1999).

The final caveat to our conceptualization of trust emerges from an understanding of how complexity-reducing mechanisms can be separated into different forms of social trust. Such separations are analogous to the divide between familiarity and trust. As we have seen, the former shies away from risk and remains in the known, while the later ventures to take a risk by making a bet about the unknown; familiarity turns towards the past, and trust towards the future (see note 6). Recent research into the nature of trust, and how it relates to the positive effects of social capital, differentiates between types of trust (Warren 2008; Rothstein and Stolle 2008). Similarly to politics, trust can expand possibilities and prosperity, but it can also contract possibilities. Whether the former or the latter is accomplished depends upon the type and degree of trust. Prosperity and democratic rule are contingent on a higher order of trust.

Efficiency in an increasingly complex world is contingent on expanding trust beyond the habitual world. Taking a leap into the unknown enables more possibilities and reduces interaction costs. The literature differentiates between particularized And generalized trust. The former defines relations of trust that exist in networks of close relations where trust is conferred to members of an in-group, who have intimate knowledge of one another. The similarity to familiarity is evident. The generalized form refers to trust that goes beyond the familiar world and is essential to the functioning of a complex society where a member cannot possibly know everything about all the contingencies a decision requires from him or her. It is only in the form of generalized trust that social trust fulfills the function that Robert Putnam assigns to it in his definition of social capital as "networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual cooperation" (1993).

The ambivalent nature of trust in political situations is at the center of what is termed the "democratic dilemma," which ties together social and political trust. The dilemma arises out of the reality that requires trust but in which "goods conflict, collective action, and collectively binding decisions" are constantly undermining naturally accumulated trust. Respectively, they are the source of dissension, "us-them" boundaries, and unequal realizations of individual and group interests. Such facets of political situations are much more prevalent in the public policies of democratic societies and require that political actors have significant trust in the legitimacy of the outcome (Tilly 2005, 134).

Material interests or interests related to identities often trump ethical norms in politics. Where the common good should be an overriding concern, the particular interests of certain parties often come to dominate the public arena and groups draw on resources such as power and money to further their agendas. This calls for institutions that hold organized power in check and protect the public good. However, to build effective checks on sovereign power, citizens have to trust one another without actually knowing each other. Here generalized forms of trust are of crucial importance. In the next section, I will explain how distrust and trust function in political systems and then bring together the concepts and tools discussed in order to propose an answer to the Colombian conundrum outlined at the beginning of this essay: that is, the question of why high levels of criminal and political violence persist despite the existence of democratic institutions.

4. Bringing Parapolitica and Trust Together

To move forward, we need to bring together the discussion of empirical studies focusing on the issues of violence, violent actors, and clientelism in Colombia, and the analysis of sociological terms regarding the issue of trust in society. The thesis of this essay states that Colombia represents a particular type social trap, namely the generalization of particularized trust. In order to make this argument fully intelligible, I will embed the notions of generalized and particularized trust discussed in the previous section in ideal-type considerations of structures of trust in political systems. This will help to show that groups that demonstrate internal and tightly-knit trust relations can offset structures of trust and distrust that function in constitutional democracies. Such relations between rulers and ruled are crucial for ensuring the rule of law and the predictability of coercion-precisely the factors that are missing or gravely damaged in Colombia.

In many ways, this idea of the social trap sounds like a conceptualization from game theoretic studies into non-cooperative situations. However, while it certainly shares important aspects with rational choice theories, it also diverges from these theories in a number of significant ways. Laying out these differences and defining the social trap more precisely is a good starting point for the final discussion of this paper. Rothstein argues that everyone can win if everyone chooses to cooperate, e.g., pay their taxes. If most people, however, cannot trust that "almost everyone will co-operate," non-cooperation is the rational course of action, meaning that cooperation for common purposes is only likely to occur if people trust that most other people will also choose to cooperate. Lacking that trust, the social trap will slam inexorably shut. While this conceptualization shares the understanding that political and economic actions are strategic, because people's actions depend on what they believe others are going to do, with game theoretic situations, it also contains nuanced differences. The concept involves a clear distinction between individual and collective rationality, which makes utility maximization equations less useful for predicting sub-optimal outcomes. Rational action in such instances is not contingent on individual preferences, but on social context and collective memory. The contingency on collective memory makes exiting social traps intrinsically difficult, because "we cannot rationally decide to forget" (Rothstein 2005, 13; italics in the original).

The utility of the social trap concept for an analysis of Colombia's situation becomes intelligible once we insert the democratic dilemma of trust into the differentiation between democratic and authoritarian regimes. Here it reappears as an apparent paradox: democracy requires trust amongst citizens, yet the very concept of a liberal democracy rests on the notion that sovereign power cannot be trusted (Warren 1999; Sztompka 1999). This apparent contradiction is resolved by institutionalizing trust and distrust in opposite directions. In order to control the abuse of power by the sovereign, liberal democracies involve institutions and mechanisms that disperse power. In such a case, we can talk about the institutionalization of distrust. However, democracy does not entail solely the institutionalization of distrust, but encapsulates something that we can call the "institutionalization of public reason." Public reason depends on communication amongst citizens, tolerance for other opinions, the replacement of struggle and conflict with compromise and consensus, civility in public disputes, and participation (Sztompka 1999). The institutionalization of these ideals comes in the form of citizens' rights: the right to free speech, freedom of assembly, and a free press. Viewed then as a sociological ideal type, the resulting relationship between rulers and ruled is a trusting one, and constitutes what I call "institutionalized trust." Distrust and trust in constitutional democracies have the functional imperative of shifting politics from a mode of conflict to deliberation and participation and, in turn, generate generalized trust amongst citizens, guaranteeing that political outcomes will enjoy legitimacy (Warren 1999).

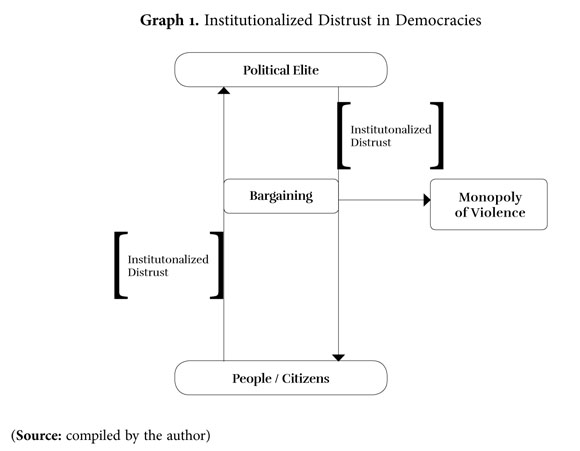

Graph 1 schematizes this configuration of institutions and socio-political trust. It shows two loci of institutionalized trust and distrust in democracies. Distrust is institutionalized vis-à-vis power. It runs bottom-up. Meanwhile, trust is institutionalized and oriented towards citizens in the form of rights and freedoms. It flows top-down.

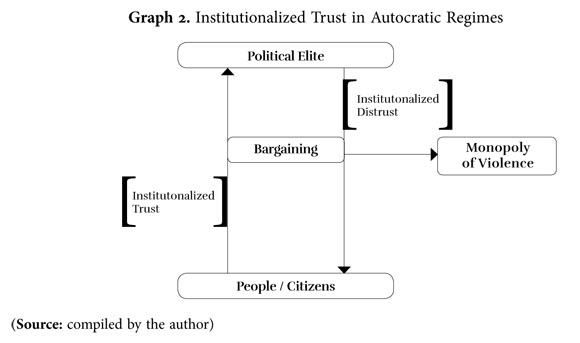

Graph 2 schematizes the ideal-type scenario in authoritarian regimes. Here, the institutionalization of trust and distrust runs in the exact opposite direction: the rulers are bestowed with a blind form of trust that does not question the role they play.7 Citizens, on the other hand, are bestowed with distrust, resulting in constant surveillance and the absence of rights and freedoms. This pattern follows the same logic at work in democracies, only with reversed vectors. Consequently, the institutionalization of trust towards rulers, and the institutionalization of distrust towards citizens, breeds distrust within society. In this way, given their lack of accountability to citizens and the lack of public participation by citizens, autocratic societies do not require the same levels of trust as democracies. The different ways in which trust is institutionalized within democracies and autocracies also have contrasting consequences. While autocracies breed distrust amongst citizens and force them to turn their trust inwards, democracies have the exact opposite effect, in that citizens spread their trust more openly and liberally and not just to peers or in-groups. While this only touches on the Colombian situation tangentially (after all Colombia is a democracy), the last point is important for the Colombian case, as we will see when we turn to the generalization of particularized trust.

Thus far, this study has differentiated between structures of social and political trust in democracies and autocracies. As shown, Colombia exhibits elements of democratic rule at the national level and autocratic characteristics at the sub-national level. The crucial agents that combine the two are non-state armed actors. This raises the following question: how do these actors fit into the framework of trust relations introduced above? This study, drawing on Diego Gambetta's work on the Sicilian Mafia, treats them as outwardly predatory closed trust networks, who "are first and foremost entrepreneurs in a particular commodity-protection" (1993, 15). They sell their commodity, where trust is absent. In his seminal study he shows that where mutual low-trust expectations generate the demand for guarantees to be provided in business transactions, a Don Peppe steps in to guarantee contract obligations. This economy of trust differs from other business enterprises, in that the most quintessential components of its products are violence and coercion. Gambetta argues that mafia services are sold where trust is scarce and legitimate enforcement agencies (i.e., states) are absent. Evidently, illegal transactions fulfill both of these conditions (1993, 17). The entrepreneur must be able to coerce like a state, but cannot spread trust as widely because of the nature of its business. As a consequence, it turns trust inwards towards its group members. In the vocabulary of the trust literature, it is an in-group held together through particularized trust.

Charles Tilly identified the importance of trust networks and their subjection for the trajectory of democratization and the evolution of statehood. He argued that democratization is contingent on whether trust networks' members consent to their subjection to public politics. This consent is conditional on the government's shift away from coercion towards combinations of capital and commitments. From Margaret Levi's work, he then deduces that "democracy entails contingent consent based mainly on combinations of material incentives with shared commitment" (2005, 106). As a consequence, he argues that "the trajectory of democratization differs greatly depending on whether the previous relationships between trust networks and rulers are those of authoritarianism, theocracy, patronage, brokered autonomy, evasive conformity, or particularistic ties" (Tilly 2005, 134-135).

This investigation claims that the nature of the trust network itself does alter the road towards complete democratization and even statehood (defined in Weberian terms). Even in the case of consent by the trust network to the subjection to state power, particularized trust can have highly detrimental effects on democratic rule. The basic problem is that if particularized networks of trust are incorporated into state power, particularized trust itself is generalized. Colombia is a case in point. Paramilitaries were not enemies of the state and committed themselves, nominally, to the democratic ideal. The result, however, was far from democratic. Paramilitaries killed and massacred with almost complete impunity and a total lack of accountability. Basing their legitimacy on the absence of the central state, they in fact prevent(ed) the definite monopolization of violence by the state through replacing traditional forms of interpersonal exchange with new forms rooted in their superior capacity to coerce.

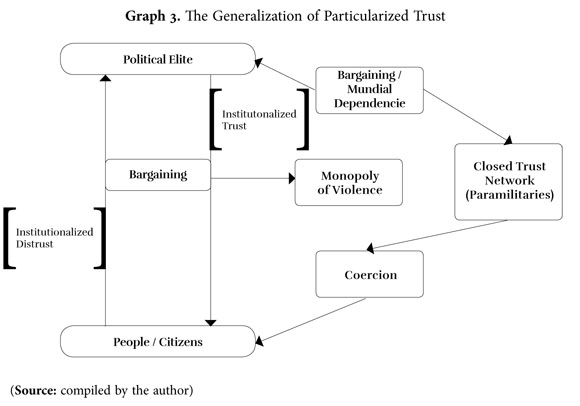

So, how can we relate these peculiar relations in Colombia with the general concepts outlined in this theoretic discussion of concepts arising out of the existing social capital literature? If we incorporate the conceptual discussion outlined above, which utilizes sociological and political theories of trust, we can tweak those concepts to better understand the Colombian paradox through the lens of social and political trust and see what constitutes the particular Colombian social trap. Schematically, the Colombian conundrum looks as shown in Graph 3.

Graph 3 schematizes the Colombian social trap. As we can see, political elites have access to the means of violence through a bargaining mechanism, which is entrenched within the framework of institutionalized distrust towards sovereign power and trust towards the people. As previously explained, this means that citizens enjoy constitutional rights, such as freedom of speech and assembly. On the other hand, political elites are kept in check through elections, the separation of power, and an independent judiciary. This institutionalized distrust prevents them from arbitrarily utilizing the instruments of the monopoly of violence for their own purposes, and forces them to go through the entrenched bargaining process. So far, this constitutes the ideal setting of a liberal democratic state rooted in the rule of law.

This ideal setting, however, is offset by what we see on the right-hand side of the graph. Political elites (at the regional level) have access to coercive means in the form of a closed trust network (paramilitaries). The only check on this predatory trust network comes in the form of the bargaining that takes place between political elites and the network. However, since the relationship is one of mutual dependence, the check on the coercion exercised by the paramilitaries is diminished or virtually non-existent. Their interests are aligned. Most importantly, the people or citizens, against whom the coercion of the paramilitaries is directed, have few ways to influence the closed trust network. In addition, the closed trust network, due to the lack of information about the loyalty of its "citizens," resorts to violence to enforce loyalty (Duncan 2006, 40). Finally, since the financing of coercive capacities emanates from external sources (drug money), those subjected to the coercive force are further distanced from those exercising the coercion (the paramilitaries). In conclusion, the incentives are structured in such a way that this structuration of socio-political trust functions as a social trap that operates predictably and systematically, reinforcing sub-optimal outcomes.

Conclusion

We began this inquiry with a paradox: the institutional and constitutional design of the Colombian state follows liberal democratic doctrines, yet, this institutional design could not prevent pervasive political and criminal violence. This ambivalence was most dreadfully displayed by the recent developments insidiously known as the parapolitica and the "false positive" scandals. This paradox begs the question of why such patterns of power abuse persist despite an institutional design that should prevent them. Research has placed this within the historical context of pervasive clientelistic relations that have undermined the full monopoly of violence by the state and resulted in an equilibrium between illegal armed groups at the periphery and politicians at the core of Colombia's political institutions.

This essay took these cues and implemented them into the existing research on social capital. It put forward the argument that trust and distrust are intrinsically linked to the functioning of the rule of law. The rule of law is what enables progressive democratization and participation. This study utilized two dichotomies within the concept of trust: first, the distinction between particularized and generalized trust, and second, institutionalized trust and distrust. We defined trust as a risky gamble for cooperative behavior over a valued good. Particularized trust refers to making this gamble with members of an in-group of whom the truster has intimate knowledge, and therefore, risks relatively little. Generalized trust is the extension of trust beyond the familiar world. Democracies require the latter form of trust, since public policies in democracies tend to exacerbate oscillation and conflict over goods and issues. In order for this kind of trust to function in political situations, which were defined as situations of possible malignant intent in which interests and identities are often in conflict, democracies rely on a framework of institutionalized trust and distrust. Political elites who may exercise the monopoly of violence are restrained by institutionalized distrust in the forms of constitutional constraints on their ability to utilize coercion. The people or citizens, however, are bestowed with trust in the form of constitutional rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the right to vote.

This normative framework of trust and democratic governance works in conjunction with established political power. Hobbes already knew that in a polity with an established monopoly of violence, said monopoly minimizes the risks of dying a violent death at the hands of another individual. In Weber's normative model, the state is the only legitimate purveyor of violence, which therefore generates the trust required for citizens to engage non-violently in political disputes.

Colombia's social trap arises out of the necessity of establishing a monopoly of violence over an internal insurgency, a process which utilized not only the armed forces but also paramilitaries with direct ties to the drug trade. These paramilitaries constitute closed trust networks, which generate particularized trust amongst their members and turn predatory towards outsiders. As Graph 3 illustrated, utilizing such a closed trust network offsets the institutionalized distrust embedded in the Colombian institution. I call this the generalization of particularized trust.

When the paramilitaries were incorporated into the struggle against the insurgency, the state was using closed trust networks. The problem here is that if particularized networks of trust are incorporated into state power, particularized trust itself is generalized. Generalizing particularized trust functions as a social trap, because it undermines the rule of law in a polity. Even if the constitutional prerequisites for the rule of law exist, closed trust networks circumvent the rule of law and, therefore, replace law itself. Law in such circumstances only exists in the form of violent coercion exerted against the people, while the people have no direct point of access to those exercising that violence or ability influence the application of coercion.

Comentarios

* The article is based on the author's MA thesis submitted at the University of British Columbia (Canada). In its first articulation, the paper was a theoretical piece on social trust literature and how it can be made utilizable for the Colombian case. The article was elaborated under the supervision of Prof. Mark E. Warren.

1 The author would like to thank Mark E. Warren, Maxwell A. Cameron, Katrina Chapelas and Samuel T. Reed for their comments on various drafts of this paper. Any mistakes that remain are his own.

2 The parapolitical scandal involved members of congress, who had signed pacts of mutual support with paramilitaries that had been involved in massacres and other human rights abuses. The false positives involved the military, also in collaboration with paramilitaries, kidnapping pauperized youth, executing them, and then presenting the bodies in guerrilla uniforms in order to receive bonuses and promotions.

3 Similarly, Michael Mann argued that increases in state power also signaled a shift from despotic power to infrastructure power. In the case of the former, the state acts despotically over society and in the case of the latter it co-ordinates Activities through society. In other words, increasing modernization alters the mode of state-society relations from coercion to coordination (1984).

4 Human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Cinep, and the United Nations have estimated the various paramilitary fractions to be responsible for up to 80% of the non-combatant and politically-motivated killings. See annual country reports by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch 1999-2005.

5 Romero (2000) was amongst the first to note that paramilitaries play a crucial role in identity formation in the territories under their control. The Group and Center for Historical Memory, implemented after the Justice and Peace Law, confirmed the overlaying of various identities in areas affected by the conflict. See in particular the 2012 reports Justicia y paz. ¿Verdad judicial o verdad histórica? (CMH 2012a ) and Justicia y paz. Tierras y territorios en las versiones de los paramilitares (CMH 2012b).

6 Familiarity pertains to a world that the observer can directly prove or disprove. The familiar, rooted in past experiences, dominates the present and the future; "complexity is reduced at the outset," while trust "goes beyond the information [the subject] receives and risks defining the future" (Luhmann 1979, 20; see also Warren 1999). Familiarity is related to a testable cognitive experience, which reduces complexity by essentially eliminating it. If it becomes a form of trust, it is, as I will demonstrate below, a different form of trust and not the type that Putnam (1993) included in his definition of social capital.

7 For ideal-type consideration, it does not matter whether those in power are feared or in fact blindly trusted. Without accountability mechanisms such as elections and term limits, the exercise of power resembles the blind trust of interpersonal relationships.

References

1. Acemoglu, Daron, James A. Robinson, and Rafael J. Santos. 2010. The Monopoly of Violence: Evidence from Colombia. NBER Working Paper No. 15578. [Online] http://www.nber.org/papers/w15578.pdf?new_window=1 [ Links ]

2. Archer, Ronald. 1989. The Transition from Traditional to Broker Clientelism in Colombia: Political Stability and Social Unrest. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Latin American Association in Miami, Florida. [ Links ]

3. Archer, Ronald, and Matthew S. Shugart. 1997. The Unrealized Potential of Presidential Dominance in Colombia. In Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, eds. Scott P. Mainwaring and Matthew S. Shugart, 110-159. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

4. Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Human Condition. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [ Links ]

5. Bejerano, Ana María, and Eduardo Pizarro. 2001. From "Restricted" to "Besieged": The Changing Nature of the Limits to Democracy in Colombia. In The Third Wave of Democratization in Latin America. Advances and Setbacks, eds. Frances Hagopian and Scott P. Mainwaring, 235-260. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

6. Centeno, Miguel Ángel. 2002. Blood and Debt. War and the Nation-State in Latin America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [ Links ]

7. Centro de Memoria Histórica [CMH]. 2012a. Justicia y paz. ¿Verdad judicial o verdad histórica. Bogotá: Centro de Memoria Histórica, Taurus. [ Links ]

8. Centro de Memoria Histórica [CMH]. 2012b. Justicia y paz. Tierras y territorios en las versiones de los paramilitares. Bogotá: Centro de Memoria Histórica, Taurus. [ Links ]

9. Collier, David, and Ruth Collier. 2002. Shaping the Political Arena. Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [ Links ]

10. Crisp, Brian F., and Rachael E. Ingall. 2002. Institutional Engineering and the Nature of Representation: Mapping the Effects of Electoral Reform in Colombia. American Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 733-748. [ Links ]

11. Duncan, Gustavo. 2006. Los señores de la guerra. De paramilitares, mafiosos y autodefensas en Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Planeta Colombiana. [ Links ]

12. Eaton, Kent. 2006. The Downside of Decentralization: Armed Clientelism in Colombia. Security Studies 15 (4): 533-562. [ Links ]

13. Evans, Peter, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol. 1985. Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

14. Gambetta, Diego. 1993. The Sicilian Mafia. The Business of Private Protection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

15. García Villegas, Mauricio, and Javier Eduardo Revelo Rebolledo. 2010. Estado alterado. Clientelismo, mafias y debilidad institucional en Colombia. Bogotá: Dejusticia. [ Links ]

16. Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco, Tatiana Acevedo, and Juan Manuel Viatela. 2007. Violent Liberalism? State, Conflict and Political Regime in Colombia, 1930-2006. An Analytical Narrative on State-Making. Crisis States Working Papers Series No. 2. [ Links ]

17. Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco, and Mauricio Barón. 2005. Re-Stating the State. Paramilitary Territorial Control and Political Order in Colombia (1978-2004). Crisis States Working Papers Series No. 66. [ Links ]

18. Hartlyn, Jonathan. 1989. Colombia: The Politics of Violence and Accommodation. In Democracy in Developing Countries. Latin America (IV), eds. Larry Diamond, Juan J. Linz and Seymour Matin Lipset, 249-307. Boulder: Lyenne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

19. Hartlyn, Jonathan. 1988. The Politics of Coalition Rule in Colombia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

20. Herbst, Jeffrey. 2000. States and Power in Africa. Comparative Lessons in and Control. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

21. López Hernández, Claudia. 2010. Y refundaron la patria... De cómo mafiosos y politicos reconfiguraron el estado colombiano. Bogotá: Corporación Nuevo Arco Iris. [ Links ]

22. Luhmann, Niklas. 1979. Trust and Power. Two Works by Niklas Luhmann. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

23. Mann, Michael. 1984. The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms, and Results. Archives européenes de sociologie 25: 185-213. [ Links ]

24. Martz, John D. 1997. The Politics of Clientelism: Democracy and the State in Colombia. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

25. Mazzuca, Sebastian, and James A. Robinson. 2009. Political Conflict and Power Sharing in the Origins of Modern Colombia. Hispanic American Historical Review 89 (2): 285-321. [ Links ]

26. Osterling, Jorge P. 1989. Democracy in Colombia. Clientelist Politics and Guerrilla Warfare. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

27. Peñate, Andrés. 1998. El sendero estratégico del ELN: del idealismo guevarista al clientelismo armado. Bogotá: CEDE. [ Links ]

28. Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

29. Robinson, James A. 2013. Colombia: Another 100 Years of Solitude? Current History 112 (751): 43-48. [ Links ]

30. Romero, Mauricio. 2000. Changing Identities and Contested Settings: Regional Elites and the Paramilitaries in Colombia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 14 (1): 51-69. [ Links ]

31. Rothstein, Bo. 2005. Social Traps and the Problem of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

32. Rothstein, Bo, and Dietlind Stolle. 2008. Political Institutions and Generalized Trust. In Handbook of Social Capital, eds. Dario Castiglione, Jan W. Van Deth, and Guglielmo Wolle, 273-330. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

33. Sánchez, Gonzalo, and Donny Meertens. 2001. Bandits, Peasents and Politics. The Case of "La Violencia" in Colombia. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

34. Sánchez, Fabio, and María del Mar Palau. 2006. Conflict, Decentralization and Local Government in Colombia, 1974-2004. Bogotá: CEDE. [ Links ]

35. Schmitt, Carl. 2002. Der Begriff des Politischen. Berlin: Duncker & Humboldt. [ Links ]

36. Spruyt, Hendrik. 1994. The Sovereign State and its Competitors. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

37. Sztompka, Piotr. 1999. Trust. A Sociological Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

38. Taylor, Steven L. 2009. Voting Amid Violence. Electoral Democracy in Colombia. Boston: Northeastern University Press. [ Links ]

39. Thoumi, Francisco E. 2003. Illegal Drugs, Economy, and Society in the Andes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

40. Thoumi, Francisco E. 1995. Political Economy and Illegal Drugs in Colombia. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

41. Tilly, Charles. 2005. Trust and Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

42. Tilly, Charles. 2004. Contention and Democracy in Europe, 1650-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

43. Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion, Capital, and European State, Ad 990-1992. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

44. Tilly, Charles. 1985. War Making and State Making as Organized Crime. In Bringing the State Back In, eds. Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol, 169-192. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

45. Valencia Villa, Hernando. 2012. Cartas de batalla. Una crítica del constitucionalismo colombiano. Bogotá: Panamericana. [ Links ]

46. Warren, Mark E. 2008. The Nature and Logic of Bad Social Capital. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Capital, eds. Dario Castiglione, Jan W. Van Deth, and Guglielmo Wolleb, 122-149. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

47. Warren, Mark E. 1999. Democracy & Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

48. Weber, Max. 1994. Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]