Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.83 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2015

https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint83.2015.02

Coauthorship Ties in the Colombian Congress, 2002-2006*

Eduardo Alemán**

** Is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston (US). He holds a PhD in Political Science and a Master's degree in Latin American Studies, both from University of California, Los Angeles. He specializes in the comparative analysis of political institutions and Latin American politics. Professor Alemán has published articles in such journals as World Politics, Comparative Politics, Comparative Political Studies, and Legislative Studies Quarterly. E-mail: ealeman2@uh.edu

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint83.2015.02

ABSTRACT

This paper examines policy connections between Colombian legislators (representatives and senators) during álvaro Uribe's first presidential term (2002-2006). The analysis draws on information regarding the coauthorship of legislation. The joint sponsorship of a bill by a pair of legislators demonstrates their mutual intent to change the status quo in a specific direction. This cooperative effort to push bills forward reveals the similarities that exist between political actors. Examining the connectedness between different groups and the density within group connections can convey important information about parties and their members' policy preferences. This article investigates these aspects of the network of coauthorship ties developed in the Colombian lower and upper chambers. In addition to shedding light on the cohesiveness and alignment of legislative parties, the article finds that coauthorship ties appear to be influenced by regional and institutional forces.

KEYWORDS

Congress, political parties, coauthorship, Colombia, networks

Coautoría de propuestas legislativas en el Congreso de Colombia, 2002-2006

RESUMEN

En este artículo se examinan las conexiones políticas existentes entre los legisladores colombianos (representantes y senadores) durante la primera presidencia de álvaro Uribe (2002-2006). El análisis utiliza información acerca de la coautoría de propuestas legislativas. La iniciación de las mismas por un par de legisladores indica la intención de ambos de cambiar el statu quo en una dirección específica. Esta cooperación para promover propuestas legislativas revela las similitudes que existen entre los actores políticos. Examinar las conexiones entre los diferentes grupos y la densidad de las conexiones existentes dentro de estos grupos nos puede informar acerca de los partidos y de las preferencias políticas de sus miembros. En este artículo se investigan estos aspectos de la red de conexiones establecidas en las cámaras del Congreso colombiano a través de la coautoría de propuestas legislativas. Además de explicar la cohesión y el alineamiento de los partidos, este artículo encuentra que las conexiones basadas en la coautoría son también influenciadas por aspectos institucionales y regionales.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Congreso, partidos políticos, coautoría, Colombia, redes

Coautoria de propostas legislativas no Congresso colombiano, 2002-2006

RESUMO

Neste artigo, examinam-se as conexões políticas existentes entre os legisladores colombianos (representantes e senadores) durante a primeira presidência de álvaro Uribe (2002-2006). A análise utiliza informação sobre a coautoria de propostas legislativas. A iniciação destas por um par de legisladores captura a intenção de ambos de mudar o statu quo numa direção específica. Essa cooperação para promover propostas legislativas revela as similitudes que existem entre os atores políticos. Examinar as conexões entre os diferentes grupos e a densidade das conexões existentes dentro desses grupos pode informar-nos a respeito dos partidos e das preferências políticas de seus membros. Neste artigo, pesquisam-se esses aspectos da rede de conexões estabelecidas nas câmaras do congresso colombiano por meio da coautoria de propostas legislativas. Além de iluminar a coesão e o alinhamento dos partidos, este artigo constata que as conexões baseadas na coautoria são também influenciadas por aspectos institucionais e regionais.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Congresso, partidos políticos, coautoria, Colômbia, networks

Introduction

The literature on legislative politics has long been concerned with understanding and measuring the policy positions of members of congress and the unity of political parties. The main data source used to evaluate party cohesion and map the preferences of legislators has been recorded congressional votes. The information derived from recorded votes offers many advantages in terms of uncovering the individual and partisan positions manifested in congress, but it is not always available. While in some countries, like the United States, Chile, or Peru, congressional votes are systematically recorded, in many countries the positions legislators take on these votes are not documented at all or are recorded only occasionally and under special circumstances. The lack of a systematic voting record has led scholars interested in evaluating the positions of legislative actors to rely on other data sources, such as public opinion data, expert assessments, and surveys of legislators. These alternative techniques illuminate important aspects of legislative positioning in congress, but do not rely on actual legislative behavior to draw their results. One useful alternative is to utilize information on bill initiation. Recent studies have used data on the cosponsoring of bills to study the policy connections between legislators and the relationships between different partisan groups (Talbert and Potoski 2002; Crisp, Kanthak, and Leijonhufvud 2004; Alemán 2009; Alemán and Calvo 2013).

In this article, I examine the network of policy connections developed by Colombian legislators (representatives and senators) during the first presidential term of álvaro Uribe (2002-2006). During the period studied, congressional votes were not systematically recorded.1 However, bill initiation data are available and provide an alternative source for examining the policy positions of Colombian legislators and parties.

The examination of the network of policy connections developed in congress during álvaro Uribe's first presidential term is particularly relevant for two different reasons. Firstly, the party system was in disarray and the extent to which members of the different partisan groups held cohesive policy stances is unclear. Moreover, legislators' ideological self-placement reveals partisan groups that are, for the most part, undifferentiated. In this article, I investigate whether the apparent blurring of ideological lines and organizational coherence is reflected in the connections which legislators establish when they coauthor bills. The empirical analysis should shed light on whether or not the non-ideological view derived from surveys characterizes congressional behavior. Likewise, it should show to what extent partisan alignments are consistent with the ideological stances once associated with the main partisan group.

The second reason relates to a particularly salient political event that took place during the period under investigation. A sizable share of the membership of congress during those years became involved in a major political scandal, dubbed parapolítica, which linked legislators and other politicians from various parties to illegal paramilitary organizations. In principle, there is no reason to suppose that members linked to the parapolítica scandal should themselves be connected through bill coauthorship beyond what is to be expected considering their shared individual traits (party, region, tenure, etc.) and institutional context (chamber, committee, etc.). Whether the implicated members were also connected through policy remains unexplored and reflects the latent similarities among the accused. The empirical analysis presented in this article sheds light on these points by evaluating the network of connections derived from legislators' joint policy stances.

The rest of this article is divided into five parts. The first one discusses how the analysis of bill initiation networks can illuminate important aspects of legislative politics. The second part derives some specific expectations about the coauthorship ties developed among Colombian legislators during álvaro Uribe's first presidential term (2002-2006). The third part explains the models applied. The fourth part presents the results, and a brief conclusion is presented in the fifth part.

1. The Network of Policy Ties

The links that legislators develop by jointly proposing bills form a network of policy connections. Legislators tend to connect with others with whom they share some policy preferences as well as an interest in similar policy areas (Alemán and Calvo 2013). The joint sponsorship of a bill by a pair of legislators demonstrates their mutual intent to change the status quo in a specific direction. This cooperative effort to push bills forward reveals individual preferences over legislation as well as the similarities that exist between political actors. Examining the connectedness between different groups and the density within group connections can convey important information about parties and their members' policy preferences.

Many studies describe bill initiation as an instrument for communicating policy positions. Bill cosponsoring has been portrayed as a position-taking device targeting electoral constituents (Crisp et al. 2004; Balla and Nemacheck 2001; Campbell 1982; Mayhew 1974), as well as a signal to other legislators (Kessler and Krehbiel 1996; Light 1992; Wawro 2000). The use of network analysis to examine coauthorship patterns has been applied in several studies. For instance, some authors have examined how an actor's position in the network affects legislative success (Fowler 2006; Tam Cho and Fowler 2010), how political polarization affects individual connections (Alemán 2009, Zhang, Traud, Porter, Fowler, and Mucha 2008), and how coauthorship links can map legislators' policy preferences (Alemán, Calvo, and Jones 2009; Crisp et al. 2004).

This article presents an empirical analysis of the network of policy ties developed by Colombian legislators when they initiate bills. It focuses on the structure of political alignments and the cohesion of parties. The analysis focuses on the period between 2002 and 2006. The next section describes the case to be scrutinized and the main questions this study seeks to answer.

2. The Analysis of the Colombian Congress during 2002-2006

The literature has generally characterized Colombian parties as organizationally weak, undisciplined, and factionalized. Many have linked party weakness to the highly personalized nature of electoral competition. Before the 2003 reform, multiple lists from the same party were allowed to compete against each under a closed list proportional representation system with medium-size districts. Major parties often appeared in more than one list per district, and intra-party competition was common. Most importantly, since lists usually obtained enough votes only to elect the top candidate, competition centered on the personality of candidates and not on partisan positions (Botero and Rennó 2007; Archer and Shugart 1997). This independence from party organizations extended to campaign financing, as candidates raised and spent their own funds (Nielson and Shugart 1999).

Since the early 1990s, Colombia has experienced a substantial transformation of its party system, which ended the dominance of the Liberal and Conservative parties. Many new political organizations have been able to win congressional seats, and support for the two traditional Colombian parties has diminished significantly. In the 2002 election, 40 political organizations won seats in the Chamber of Deputies (Giraldo and López 2006). This increased the complexity of congressional bargaining and the importance of alliances. From the end of the National Front in the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, both major parties suffered from weak organization, factionalism, and a perverse form of candidate-centered electoral rules, but their ideological alignment seemed stable: the Liberals were positioned on the center-left and the Conservatives on the center-right (Coppedge 1997). Yet, the meltdown of the party system also coincided with a blurring of ideological differences.

Thus far, depictions of the early 2000s underline the absence of a coherent distribution of partisan positions. According to surveys of legislators from the late 1990s and early 2000s, Liberals and Conservatives did not express clearly different positions along the left-to-right dimension (Carroll and Pachón 2014). Rosas (2005, 840) concludes that in Colombia, "the partisan space is not structured by a clear-cut economic dimension." Jones' (2007) examination of ideological polarization in congress (elite surveys) and the electorate (public opinion) concludes that in Colombia such polarization is weak to non-existent. He ranks Colombia (in the early 2000s) in the lowest category in terms of programmatic politics, and characterizes its party system as clientelistic with a decentralized structure. Whether this blurring of ideological differences is also reflected in legislators' behavior remains an empirical question. It is likely that the level of internal party cohesion and coherent ideological alignments varied across the different parties.

The positions that political parties adopted were shaped by arrival of the new president. álvaro Uribe, the winner of the 2002 election, was a former senator and governor from the Liberal Party who, as an independent candidate, had run a campaign focused on security policy (i.e., confronting the leftist guerrillas) rather than on ideological grounds. Once in power, he governed as a rightist, but received the support of an ideologically heterogeneous coalition.

The largest party in Colombia, the Liberal Party, was deeply divided between supporters and detractors of President Uribe. A faction of the Liberals, together with the Conservative Party and a series of newly-formed parties, gave Uribe's first government a congressional majority. What remained of the Liberal Party took on the role of opposition. While the schism brought about by the emergence of Uribe is likely to have contributed to greater cohesion among the remaining Liberals, the 2002-2006 cohort still remained politically divided and ideologically heterogeneous. While part of its membership had incentives to forge ties with the more conservative Uribistas to promote their policies in congress, others had incentives to forge ties with other opposition members to challenge the government coalition.

In contrast to the situation of disarray faced by the Liberals, legislators associated with various leftist groups began to coalesce in opposition to the government. During Uribe's first administration, they forged new organizations, gained greater electoral support, and eventually united to support a common presidential candidate who came in second in the presidential election of 2006.2 As Uribe's political movement began to shift more clearly to a center-right position, a united left became a vocal opponent to the government.

Conservatives also had a history of internal divisions, individualism, and weak leadership. But the Uribe presidency had the opposite effect on them: unity. While Conservatives were somewhat ambivalent about Uribe in the 2002 election, there was no hesitation in their 2006 endorsement. Joining the Uribe coalition also brought Conservatives closer to the new parties that supported Uribe's government. This was a loose alliance of newly formed organizations without a significant militant base or a formal leadership structure. They included centrist (some former Liberals) and right-wingers, whose support grew with Uribe's popularity.

In the next section, I analyze the network formed by coauthoring bills to evaluate the cohesion of partisan groups and their alignment during Uribe's first presidential term. The expectations regarding the unity of the different partisan groups can be translated into testable hypotheses regarding the connections legislators develop through bill initiation. Cohesive blocs are expected to exhibit denser connections, and partisan groups that are close to each other are expected be more connected than those that stand further apart. Thus, the analysis should reveal the relative unity of partisan groups and whether there is a coherent alignment of partisan positions.

The conventional view is in this case the null hypothesis: cross-partisan ties should not exhibit a coherent ideological alignment, and within-group ties should not be significantly higher than cross-partisan ties. However, as previously noted, I expect differences across parties in terms of their common policy stances. It is unlikely that the connections developed by the divided and diverse Liberals reflect cohesive behavior. Those developed by the Leftist group, however, should be more likely to reflect unity of purpose. The historically fractious Conservatives were pulled together by a friendly government, so their level of cohesion should be somewhere in the middle. In terms of cross-partisan ties, a connection between the two center-right groups in government, Uribistas and Conservatives, should be more likely than a connection between either one of them and the Leftist group. And the latter should appear closest to the Liberals.

Accordingly, the four propositions to be examined in the empirical section are:

H1: The probability of a connection between Liberal legislators should be lower than the probability of a connection between Conservative legislators.

H2: The probability of a connection between Leftist legislators should be higher than the probability of a connection between Conservative legislators.

H3: The probability of a connection between Leftist legislators and Liberal legislators should be higher than the probability of a connection between Leftist legislators and either Uribista or Conservative legislators.

H4: The probability of a connection between Uribista and Conservative legislators should be higher than the probability of either one of them connecting with the Leftist legislators.

Regional effects are also likely to influence the tendency to coauthor bills. Representatives elected from the same geographical areas are expected to share an interest in areas of policy relevant to local constituencies (Alemán and Calvo 2013).3 In the case of Colombia, the impact of local and regional considerations is frequently considered significant. For example, according to Nielson and Shugart, "a strong case could be made that the rural-urban dimension is the most salient issue in the Colombian polity" (1999, 15). According to the authors, while presidents attempted to court the median voter, decidedly urban, members of Congress remained largely responsive to rural interests and their clienteles in the countryside. The constitutional reform of 1991 attempted to modify some of these tendencies by changing the territorial districting of Senate elections from several medium-sized districts into a single nationwide district. But the constitutional reforms also accelerated political and economic decentralization (Escobar-Lemmon 2003).4 Therefore, in the empirical analysis I control for the effects of regional background and rural populations.

Lastly, the empirical analysis can shed some light on the policy relations developed by members of congress involved in the political scandal known as parapolítica. This was a major scandal revolving around the collusion between politicians and members of illegal armed groups. The accusations ranged from promoting and receiving campaign support from paramilitaries to financing and arming illegal groups. Some legislators were even accused of complicity in murders. Information revealed by the judicial proceedings underlines the interest that paramilitary groups had in terms of seeing that particular policies were adopted. The evidence shows that legislators involved in this political scandal were more likely to belong to the Uribista parties than to other partisan groups. These members of congress were also more likely to come from rural areas. In the analysis conducted in this article, I control for partisan and rural effects, and examine whether legislators tainted by this scandal were more likely to connect to each other than to other members of congress.

3. Analyzing Policy Connections in Colombia's Congress

The empirical analysis focuses on the effects of a series of covariates on the probability that two legislative actors coauthor a bill. It is reasonable to view the density of intra-partisan connections as a reflection of the compactness of their members' policy positions: partisan groups are cohesive if their members are highly connected among themselves. Similarly, regional forces influence the connections legislators build via policy proposals if legislators are significantly more likely to develop ties with legislators from the same region than with those from other regions.

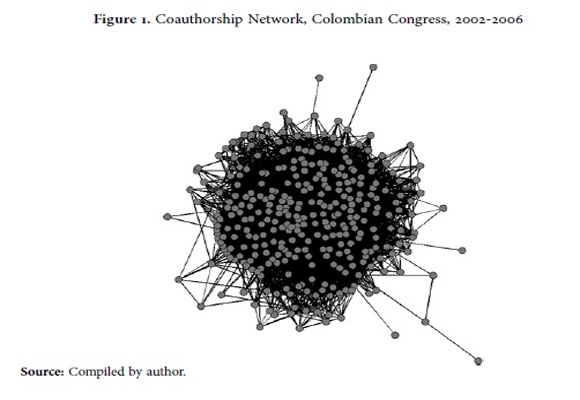

The Colombian network of coauthorship ties is composed of 343 actors. It includes all elected legislators (representatives and senators), and substitute legislators who coauthored bills. In the 2002-2006 network, the proportion of coauthorship ties present out of all possible ties is 22.8%. This is the density of the network. Some legislators coauthor bills repeatedly, which is captured by the strength of ties (i.e., the number of times two legislators connected). Figure 1 provides a picture of the network, with nodes representing legislators and dark lines representing coauthorship ties.

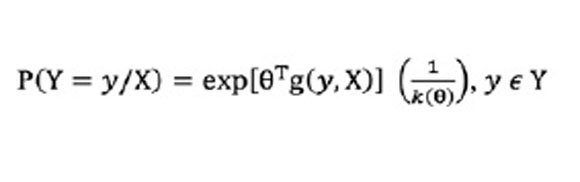

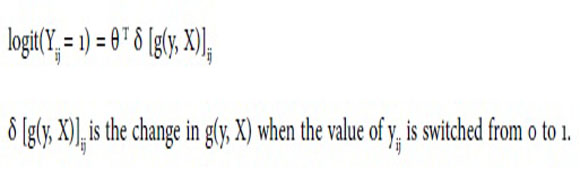

I employ a series of stochastic exponential random graph models (ERGMs) to examine the policy connections of legislative actors, which are captured by the n x n sociomatrix of coauthorship ties. An ERGM can model attributes of actors (e.g., faction membership, district, etc.) as well as the structural parameters of the network. A tie between two actors is assumed to be a random variable.5 For each i and j who are distinct members of a set N of n actors, there is a random variable Yij where Yij = 1 if there is a network tie from actor i to actor j. Yij = 0 if there is no tie from actor i to actor j. The probability of observing a set of ties is:

Y is the random set of ties in a network, y is a particular given set of ties, X is a matrix of actor attributes, g(y, X) is a vector of network statistics, θ is a vector of coefficients, and k(θ) is a normalizing constant.6 The log-odds that a tie exists given the rest of the network is:

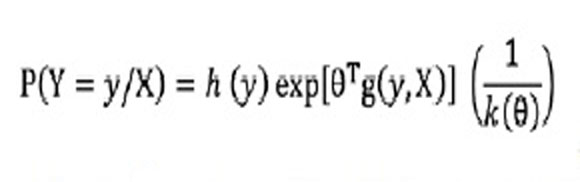

In a binary ERGM, ties have dichotomous values indicating whether each pair of legislators is connected. But policy networks also inform us about the relative intensity of the coauthorship tie. The strength of dyadic ties within a given period is captured by the number of coauthored bills. To take advantage of such data, the next section also shows results from an ERGM for counts. In a recent work, Krivitsky (2012) generalizes the ERGM framework to directly model valued networks (i.e., with ties representing counts). In this case, the sample space is a set of mappings that are assigned to each dyad (i, j) ∈ Y a count, and the value associated with the dyad is Yij = y(i, j).7 An ERGM for a random network of counts is:

The baseline distribution is captured by h (y), which also modifies the normalizing constant. Binary ERGMs use the edges term as the baseline while ERGMs for counts use the intensity (sum) term. The ERGM for counts model that appears in the next section uses a zero-inflated Poisson distribution, which requires that a non-zero term be added to the model. We do this because the policy network being analyzed is somewhat sparse and connections often have high values.

The model employed includes information on the partisan and regional background of legislative actors. Legislators are divided into five groups: Liberal (including those in the Liberal Party and in associated lists); Conservative (including those in the Conservative Party and in associated lists); Uribista (those belonging to the new parties supporting president Uribe's presidential bid); Leftist (those belonging to the PDI, AD, and associated lists); and a fifth group made up of independents and others not belonging in either of the prior four categories. Representatives are classified into five regions: Bogotá, Andina, Caribe, Costa Pacífica, and Amazonia. The model also includes information on the proportion of constituents from rural populations in each legislator's district.

Additional controls address the effects of institutions.8 The variable Chamber of Origin captures the likelihood of coauthoring with legislators from the same chamber, the variable Committee does the same for legislators that share membership of a permanent committee, and the variable Alternate captures the level of coauthoring activity among substitute legislators. In bicameral congresses, senators tend to initiate fewer bills than members of the lower chamber, and it is reasonable to expect intra-chamber bill coauthoring to be higher than cross-chamber bill coauthoring.9 Legislators who serve in the same committee often share an interest in similar policy areas, and the recurrent contact resulting from common committee service creates many opportunities to share information about preferences and policy interests (Alemán and Calvo 2013). Therefore, serving in the same committee should increase the chance of coauthoring bills. Lastly, it is also reasonable to expect substitute legislators, who serve for a shorter period of time, to coauthor bills less frequently.

4. Results

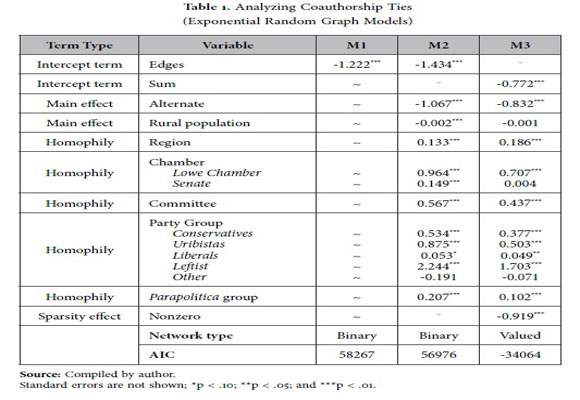

Table 1 presents the results of three alternative models.10 Stars next to the coefficient indicate statistical significance. Model 1 show results for the null model, which has a single parameter and assumes both dyadic independence and the same probability for all actors in the network. The results tell us that the log-odds of a tie is -1.222 x δ (g(y, X))ij. This coefficient corresponds with a probability of 22.7%, which is the density of the network.11 This equals the proportion of all possible ties that are actually present.

Model 2 introduces additional parameters. The coefficients for the party variables capture the chances of within-group ties, or homophily tendencies in social network parlance.12 They show that connections within party groups are always more likely than connections across the four party groups.13 However, there are important differences between these groups. The highest coefficient is for the Left, which is by far the most compact of the partisan groups. The coefficient for the Liberals is low and only borderline significant. For example, the probability of a tie between two representatives from the Leftist group (from urban districts and different regions) is 85.5%. In contrast, the probability of a tie between two representatives from the Liberal group (from urban districts and different regions) is 39.7%, which is only slightly higher than the probability of a tie between two legislators from different partisan groups (38.5%).14

The Conservative group appears to be more cohesive than the Liberal group. The probability of a tie between two representatives from the Conservative group (from urban districts and different regions) is 51.6%. While this is higher than the chance of a tie between two representatives from the Liberal group, it is still much lower than the chance of a tie between two representatives from the Leftist group. The results also show a rather compact Uribista group.15

Belonging to the same region increases the likelihood of connecting with another legislator. However, while the coefficient is positive and statistically significant, its substantive impact is relatively modest. For example, the probability that two representatives from the same region and different partisan groups coauthor a bill is 41.6%, which is 3 percentage points higher than the chance of a tie between two similar legislators from different regions. The coefficient capturing the main effect of rural populations is negative and significant, indicating that representatives coming from regions with a higher proportion of constituents from a rural population are slightly less likely to coauthor bills.

The findings also inform us about the coauthorship choices of legislators implicated in the parapolítica scandal. The coefficient labeled parapolítica is positive and statistically significant. Although the substantive impact is moderate, the results reveal an underlying policy connection among these members beyond partisan grouping and territorial origin. The probability that two legislators implicated in this scandal coauthor a bill together is 5 percentage points higher than the probability of a coauthorship tie between a different pair of legislators.

Institutional effects are also evident. Intra-chamber connections are more common in the Chamber of Representatives than in the Senate, and cross-chamber connections occur less often.16 Sharing membership in a permanent committee increases the chance of coauthoring bills. In addition, alternate legislators (i.e., suplentes) are significantly less likely to coauthor bills.

Model 3 focuses on the strength of ties. It examines the valued network that measures the number of coauthored bills between each pair of legislators. The count model employed to examine this network (zero-inflated Poisson) has a different intercept (sum instead of edges), and a term to capture the relative sparsity of connections (nonzero).

The findings from Model 3 are similar to those of Model 2. The strongest ties are between legislators belonging to the Leftist group, while the weakest intra-group ties are among the Liberals. In addition, legislators from the same region have stronger connections than those from different regions. Institutional effects are again evident. Connections are stronger between representatives than between senators. They are also stronger among members who share membership of a committee than among those who do not. The coefficient measuring intra-group ties among those implicated in the parapolítica scandal is positive and statistically significant, as in the prior model. The coefficient capturing the effect of a district's rural population, however, lacks statistical significance.

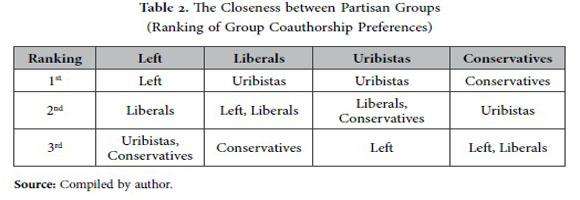

Lastly, the closeness between partisan groups can be evaluated by adding parameters for each pair-wise combination to those of Model 2. The results (not shown) reveal the most likely cross-partisan associations when coauthoring legislation. The rank ordering for each partisan group is shown in Table 2.

For each partisan group, except the Liberals, the most likely connection is with members of the same group. Legislators in the Liberal group, however, are more likely to connect with Uribistas than with other Liberals. They are also as likely to connect with legislators in the Leftist group as they are to connect with other Liberals. Liberals are least likely to connect with Conservative legislators, their historic rivals. As expected, the probability of a connection between Leftist legislators and Liberal legislators is significantly higher than the probability of a connection between Leftists legislators and either Uribista or Conservative legislators. In addition, the probability of a connection between Uribista and Conservative legislators is higher than the probability of either one of them connecting with legislators in the Leftist group.

The ordering summarized in Table 2 is consistent with an ideological alignment that positions the Conservatives on the right, the Uribistas on the center-right, Liberals spanning from the center to the center-left, and the Leftist group on the left pole. The results also exemplify the lack of team-like behavior among the Liberal group.

To sum up, the findings are consistent with the idea that levels of cohesiveness vary across partisan groups. The Left appears as the most cohesive and the Liberals as the least cohesive group. The collection of Uribista parties appears more united than the Conservative group, which is still more unified than the Liberal camp. Overall, the alignment of partisan groups separates the left in opposition to the right in government, with Liberals all over the place. The analysis also finds that belonging to the same region, chamber, and congressional committee, fosters policy collaboration. Although the effect is moderate, the findings show that members of congress are more likely to connect with each other to propose policy changes if both are implicated in the parapolítica scandal

Conclusions

This study focused on the membership of congress during the first presidential term of álvaro Uribe. It applied social network analysis to examine the connections Colombian legislators develop when initiating bills. The results provide a window into the policy preferences of legislators and partisan groups. This is particularly relevant given the scant use of roll-call votes. During this period of particular fluidity in the party system, Liberal legislators demonstrated a lack of unity. However, the other groups exhibited moderate to strong cohesion and their alignment coincided with the left-to-right ideological ordering. The findings place the so-called Uribista group close to both Conservatives and Liberals. In addition, the emerging Leftist group appears tightly connected and positioned furthest away from the supporters of the government. By the end of this legislative period, the group would go on to reach the second spot in the presidential race, winning close to twice as many votes as the Liberal candidate.

This period was also marked by one of the biggest political scandals in recent decades. The findings presented here show that the chances of two legislators coauthoring a bill together are somewhat higher if both members are implicated in this scandal. The extent to which this finding reflects a latent bond among this particular group of politicians remains to be explored.

In conclusion, the analysis showed how policy connections built through the joint initiation of bills can reveal politically relevant information about legislators and their attributes. Given the scant use of roll-call votes in the Colombian congress over recent decades, the study of bill coauthorship ties offers a valuable alternative for studying legislative behavior. New techniques and software, as well as the greater availability of coauthorship data, should encourage further studies.

Comments

*Part of this research was funded by a grant from the University of Houston (#100547).

1 They occurred only occasionally in the Senate (on average less than 10 non-unanimous votes a year), and even less often in the Chamber of Representatives. Part of the reason for the lack of systematic record keeping in terms of congressional votes had to do with the violent political conflict that engulfed the country. The lack of systematic record keeping regarding congressional votes was aimed at sheltering individual legislators from possible coercion on votes that affected the particular interests of the various illegal organizations. Votes began to be recorded more systematically in 2009.

2 In 2003 a group of legislators from diverse leftist groups formed a new coalition, the Independent Democratic Pole (PDI). As the 2006 election approached, the PDI formalized an alliance with another leftist group, the Democratic Alternative (AD), leading to the creation of the Alternative Democratic Pole (PDA), which nominated the main challenger to Uribe's reelection bid. Saiegh's (2009) mapping of ideological positions (based on elite surveys taken during this time period) found a similar government-opposition divide: on the right supporters of the government (the president, the Conservative Party, and a faction of the Liberal Party alongside each other), and on the left the opposition (the Liberals in opposition on the center-left, and the leftist alliance on the far left).

3 They are also likely to share a preference for distributive policies targeted at their constituents.

4 By 2001 Colombia's subnational governments allocated over 40% of government spending, which was a higher proportion than commonly allocated in federal countries in the region, such as Argentina or Brazil (Alesina, Carrasquilla, and Echevarría 2005).

5 This summary of ERGM modeling is based on Robins, Pattison, Kalish, and Lusher (2007), and Handcock, Hunter, Butts, Goodreau, and Morris (2003).

6 See Goodreau, Handcock, Hunter, Butts, and Morris (2008, 7-8). When the model includes terms capturing endogenous effects, estimation is based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo Maximum Likelihood Estimation. A distribution of random graphs is simulated from a starting set of parameter values, and the parameter values are subsequently refined by comparing the distribution of graphs against the observed graph, repeating this process until the parameter estimates stabilize (Hunter, Handcock, Butts, Goodreau, and Morris 2008; Wasserman and Robins 2005).

7 See Krivitsky (2012)

8Data on bill initiation and committee assignments was provided by Congreso Visible, http://www.congresovisible.org

9 Cross-chamber coauthoring is allowed in Colombia.

10 I use the statnet package to run these models (Handcock et al. 2003).

11 So, in this case, density = exp(-1.222) / (1+ exp(-1.222))

12 The notion that similarity breeds connection.

13 Cross-partisan ties are not different than ties within the "Others" category, which includes independents and members of other small groups.

14 I also run this model with the addition of a structural parameter capturing the tendency to form transitive relations (GWESP in statnet). The results are very similar to those of Model 2, with the exception being that the coefficient for the Liberal group now loses statistical significance. The structural parameter is also statistically insignificant.

15 The probability of a tie between two representatives from the Uribista group (from urban districts and different regions) is 60%. This group includes Cambio Radical, Equipo Colombia, MIPOL, Convergencia Popular Cívica, and several other very small parties.

16 As in other countries with bicameral congresses, senators tend to introduce fewer bills than representatives.

References

1. Alemán, Eduardo. 2009. Institutions, Political Conflict, and the Cohesion of Policy Networks in the Chilean Congress, 1961-2006. Journal of Latin American Studies 41 (3): 467-491. [ Links ]

2. Alemán, Eduardo, Ernesto Calvo, Mark P. Jones, and Noah Kaplan. 2009. Comparing Cosponsorship and Roll-Call Ideal Points. Legislative Studies Quarterly 34 (1): 87-116. [ Links ]

3. Alemán, Eduardo and Ernesto Calvo. 2013. Explaining Policy Ties: A Network Analysis of Bill Initiation Data. Political Studies 61 (2): 356-377 [ Links ]

4. Alesina, Alberto, Alberto Carrasquilla, and Juan José Echevarría. 2005. Decentralization in Colombia. In Institutional Reforms: The Case of Colombia, ed. Alberto Alesina, 175-208. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

5. Archer, Ronald P. and Matthew S. Shugart. 1997. The Unrealized Potential of Presidential Dominance in Colombia. In Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, eds. Scott Mainwaring and Matthew S. Shugart, 110-159. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

6. Balla, Steven J. and Christine L. Nemacheck. 2001. Position-Taking, Legislative Signaling, and Non-Expert Extremism: Cosponsorship of Managed Care Legislation in the 105th House of Representatives. Congress & the Presidency 27 (2): 163-188. [ Links ]

7. Botero, Felipe and Lucio R. Rennó. 2007. Career Choice and Legislative Reelection: Evidence from Brazil and Colombia. Brazilian Political Science Review 1 (1): 102-124. [ Links ]

8. Campbell, James. 1982. Co-Sponsoring Legislation in the U.S. Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly 7 (3): 415-422. [ Links ]

9. Carroll, Royce and Mónica Pachón. 2014. The Unrealized Potential of Presidential Coalitions in Colombia. To be included in Legislative Institutions and Lawmaking in Latin America, eds. Eduardo Alemán and George Tsebelis. [ Links ]

10. Coppedge, Michael. 1997. A Classification of Latin American Party Systems. Working Paper 244. Notre Dame: Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame. [ Links ]

11. Crisp, Brian F., Kristin Kanthak, and Jenny Leijonhufvud. 2004. The Reputations Legislators Build: With Whom Should Representatives Collaborate? American Political Science Review 98 (4): 703-716. [ Links ]

12. Escobar-Lemmon, María. 2003. Political Support for Decentralization: An Analysis of the Colombian and Venezuelan Legislatures. American Journal of Political Science 47 (4): 683-697. [ Links ]

13. Fowler, James. 2006. Connecting the Congress: A Study of Cosponsorship Networks. Political Analysis 14 (4): 456-487. [ Links ]

14. Giraldo, Fernando and José Daniel López. 2006. El comportamiento electoral y de partidos en los comicios para Cámara de Representantes de 2002 y 2006: un estudio comparado desde la Reforma Política. Colombia Internacional 64: 122-153. [ Links ]

15. Goodreau, Steven M., Mark S. Handcock, David R. Hunter, Carter T. Butts, and Martina Morris. 2008. A Statnet Tutorial. Journal of Statistical Software 24 (9): 1-26. [ Links ]

16. Handcock, Mark S., David R. Hunter, Carter T. Butts, Steven M. Goodreau, and Martina Morris. 2003. Statnet: Software Tools for the Statistical Modeling of Network Data. University of Washington. [Online] http://statnetproject.org [ Links ]

17. Hunter, David R., Mark S. Handcock, Carter T. Butts, Steven M. Goodreau, and Martina Morris. 2008. ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks. Journal of Statistical Software 24 (3): 1-28. [ Links ]

18. Jones, Mark P. 2007. Political Parties and Party Systems in Latin America. Paper prepared for the symposium Prospects for Democracy in Latin America. Denton: Department of Political Science, University of North Texas. [ Links ]

19. Kessler, Daniel and Keith Krehbiel. 1996. Dynamics of Cosponsorship. American Political Science Review 90 (3): 555-566. [ Links ]

20. Krivitsky, Pavel N. 2012. Exponential-Family Random Graph Models for Valued Networks. Electronic Journal of Statistics 6: 1100-1128. [ Links ]

21. Light, Paul C. 1992. Forging Legislation. New York: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

22. Mayhew, David. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

23. Nielson, Daniel L. and Matthew S. Shugart. 1999. Constitutional Change in Colombia: Policy Adjustment through Institutional Change. Comparative Political Studies 32 (3): 313-341. [ Links ]

24. Robins, Garry, Pip Pattison, Yuval Kalish, and Dean Lusher. 2007. An Introduction to Exponential Random Graph (p) Models for Social Networks. Social Networks 29: 173-191. [ Links ]

25. Rosas, Guillermo. 2005. The Ideological Organization of Latin American Legislative Parties: An Empirical Analysis of Elite Policy Preferences. Comparative Political Studies 38 (7): 824-849. [ Links ]

26. Saiegh, Sebastián M. 2009. Recovering a Basic Space from Elite Surveys: Evidence from Latin America. Legislative Studies Quarterly 34 (1): 117-145. [ Links ]

27. Talbert, Jeffery C. and Matthew Potoski. 2002. Setting the Legislative Agenda: The Dimensional Structure of Bill Cosponsoring and Floor Voting. Journal of Politics 64 (3): 864-891. [ Links ]

28. Tam Cho, Wendy K. and James H. Fowler. 2010. Legislative Success in a Small World: Social Network Analysis and the Dynamics of Congressional Legislation. The Journal of Politics 72 (1): 124-135. [ Links ]

29. Wasserman, Stanley and Garry Robins. 2005. An Introduction to Random Graphs, Dependence Graphs, and p. In Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis, eds. Peter J. Carrington, John Scott, and Stanley Wasserman, 148-161. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

30. Wawro, Gregory. 2000. Legislative Entrepreneurship in the U.S. House of Representatives. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

31. Zhang, Yan, A. J. Friend, Amanda L. Traud, Mason A. Porter, James H. Fowler, and Peter J. Mucha. 2008. Community Structure in Congressional Cosponsorship Networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 387 (7): 1705-1712. [ Links ]

RECEIVED: May 5, 2014 ACCEPTED: July 22, 2014 REVISED: September 4, 2014