Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.83 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2015

https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint83.2015.09

Capital Account Policy in South Korea: The Informal Residues of the Developmental State*

Ralf J. Leiteritz **

** Holds a PhD in Development Studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science, London, (UK). He is an Associate Professor at the School of Political Science, Government, and International Relations and a researcher at the Center for Political and International Studies (CEPI) at the Universidad del Rosario (Colombia). His areas of research are related to international political economy, in particular international finance in Latin America. His latest research project analyzes the political and economic relations between China and several Latin American countries. In addition, he is the editor of the journal Desafíos, published by CEPI. E-mail: ralf.leiteritz@urosario.edu.co

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint83.2015.09

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the political dynamics of capital account policy in South Korea. The first part is devoted to the historical evolution of capital account policy from the 1960s to the present day. It highlights the path of substantial financial opening that began in the early 1990s with two distinct waves of capital account liberalization before and after the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. The second part of the paper aims to detect the political origins of why capital account liberalization has not been complete and sustained. It locates them at the level of domestic informal institutions: first, the ideational legacy of the previous developmental state model – economic nationalism – that was predicated upon substantial barriers to international capital movements. Second, the political power of the export-oriented sector, namely of large conglomerates, that prefer exchange-rate stability and thus restrictions on capital inflows. This paper offers a heuristic argument based on a single case study which needs to be subjected to further empirical testing.

KEY WORDS

South Korea, capital account policy, national economic identity, international political economy

La Política de la cuenta de capitales de Corea del Sur: los residuos informales del Estado desarrollista

RESUMEN

El propósito del presente documento es analizar las dinámicas políticas de la política de cuenta de capital de Corea del Sur. La primera parte del texto se dedica a la evolución histórica de la política de cuenta de capital desde los años sesenta hasta la actualidad. En esta sección se destaca el camino de la gran apertura financiera que inició a principios de los noventa con dos olas de liberalización de cuenta de capital antes y después de la crisis financiera asiática de 1997-1998. La segunda parte del texto intenta detectar los orígenes políticos para establecer la razón por la cual la liberalización de la cuenta de capital no fue completa y prolongada. La respuesta a esto se puede encontrar a nivel de las instituciones domésticas informales: primero, el legado ideológico del modelo desarrollista estatal anterior -nacionalismo económico-, que establecía barreras significativas para los movimientos internacionales de capital. En segunda instancia, el poder político del sector orientado a la exportación, compuesto por grandes conglomerados (chaebols), que preferían estabilidad cambiaria y, por lo tanto, restricciones en los flujos de capital.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Corea del Sur, Política de la cuenta de capital, Identidad económica nacional, economía política internacional

A política da balança de capitais da Coreia do Sul: os resíduos informais do Estado desenvolvimentista

RESUMO

O propósito deste documento é analisar as dinâmicas políticas da política de balança de capital da Coreia do Sul. A primeira parte do texto está dedicada à evolução histórica da política de balança de capital desde 1960 até a atualidade. Nessa seção, destaca-se o caminho da grande abertura financeira que iniciou a princípios de 1990 com duas ondas de liberalização de balança de capital antes e depois da crise financeira asiática de 1997-98. A segunda parte do texto tenta detectar as origens políticas para estabelecer a razão pela qual a liberalização da balança de capital não foi completa e prolongada. A resposta a isso pode ser encontrada no âmbito das instituições domésticas informais: primeiro o legado ideológico do mercado desenvolvimentista estatal anterior -nacionalismo econômico- que estabelecia barreiras significativas para os movimentos internacionais de capital. Em segunda instância, o poder político do setor orientado à exportação, composto por grandes conglomerados (chaebols), que preferiam estabilidade cambiária e, portanto, restrições nos fluxos de capital.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Coreia do Sul, política de balança de capitais, identidade econômica nacional, economia política internacional

Introduction

Economic policy cannot be understood apart from ideology and politics. Whereas ideology – a complex weaving of values and beliefs – shapes a metastructural foundation or a vision for analytic constructs of economic models and economic policymaking, politics dictates actual policy outcomes through mediation, bargaining, or power struggle. (Moon 1999, 1)

This paper aims to understand the historical trajectory and the current shape of South Korea's political economy in general, and of one particular economic policy area: capital account management. This issue is embedded in a set of more general questions: To what extent does the government interfere with the flow of international capital, especially short-term flows, coming into and leaving the country? How can we explain the difference between countries in the regulation of international capital flows? Are the same factors that drive capital account policy in Latin America at play in South Korea?

In order to answer these questions, I have divided this paper into two main sections: first, a short overview of the historical trajectory of capital account policy in South Korea from the 1960s to the present day, and second, an attempt to explain the current shape of capital account policy with an explanatory variable that I have developed in the context of Latin America's political economy: national economic identity (Leiteritz 2012).

1. Historical Description of Capital Account Policy in South Korea

- a. The Traditional System: The Developmental State with a Closed Capital Account

Managing international capital flows formed part and parcel of South Korea's development model starting in the early 1960s under President Park Chung-Hee (Cho 1989, Woo 1991). A close symbiotic partnership – also labelled "developmental alliance" (Hundt 2009) – between the state and the private sector emerged during that time in order to propel South Korea, one of the most backward countries in East Asia at the time, towards fast economic growth (Amsden 1989; Wade 1990; Onis 1991; Evans 1995; Kang 2002; Wong 2004). Underpinning this system – called Kwanchi Kumyung, or, as some would say, "the heart of the developmental state" (Woo-Cumings 1999) – was the strict control the state maintained over all forms of finance, most importantly credit allocation, throughout the course of Park's regime. The Korean government controlled all internal and international transactions until the early 1990s, as well as the commercial banking sector, and intervened extensively in the stock and security markets.

The state provided financial assistance in the form of subsidies for family-owned conglomerates, known as chaebol, against clear standards and criteria for export performance. The resources for these "policy loans" were secured from foreign financial institutions and channelled through state-owned banks. An integral part of this strategy was the setting of artificially low interest rates in order to create conditions of acute credit shortage and thus justifying official credit rationing. Especially favored firms or projects were able to secure foreign loans from the state, both of which carried an interest rate much lower than the official commercial rate. This system of financial control was reinforced by systems of direct subsidy, licence allocation and arbitrary political intervention, leading in the final instance to the outright confiscation of assets (Woo 1991).

Until 1986, South Korea had suffered from chronic current account deficits, which motivated and enabled its government to enforce strict foreign exchange controls. The two pillars of these controls were the so-called Foreign Exchange Concentration System, under which all foreign exchange had to be surrendered to the central bank, and the Foreign Exchange Transaction Act (still in existence today; see below), which put severe restrictions on the use of foreign exchange, e.g., limits on overseas remittances, on overseas real estate acquisition, and even on expenditure on foreign tourism, which was severely restricted until the late 1980s.

The country did tap international capital markets extensively, mostly to finance imports of capital goods. However, all loans were subject to government approval and were intermediated by state-owned banks. Authorities strictly regulated foreign direct investment, which was not regarded as a source of finance but rather as a threat to development, and did not permit foreign portfolio investment. While no restrictions existed for the inflow of foreign capital via inter-bank loans, various restrictions existed for capital outflows, including multiple exchange rates.

The bank-based financial system was centered on directed, though indirect finance: formal or informal state guarantees for bank loans to private firms for state-mandated investments. Banks, in turn, did not act as independent actors driven by market dynamics or profit-seeking motives. Their role was squarely embedded as the vicarious agents of a state-driven and controlled growth model.

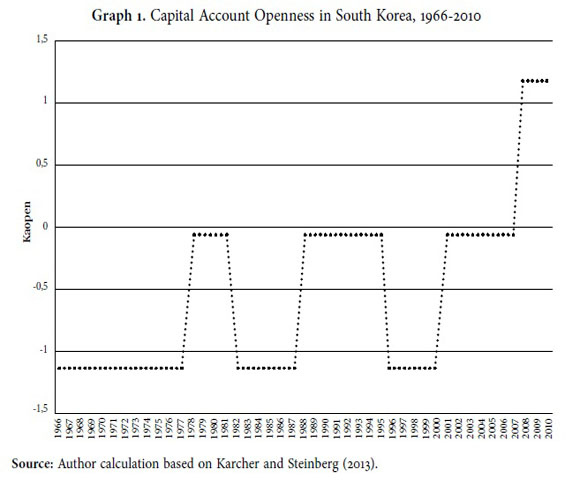

Taken together, during the high-growth period from the late 1960s to the early 1990s,1 South Korea's capital account was characterized by its closed nature (see graph 1). International capital entered the country only in the form of debt flows, highly regulated and heavily controlled by the state. As a result, the domestic financial industry was poorly developed (both institutionally and in terms of product diversification and depth), centered primarily on channeling state-guaranteed foreign loans to the private sector in exchange for export performance.

- b. The First Wave of Capital Account Opening: Asymmetric Integration into International Financial Markets

This traditional setup changed dramatically in two distinct waves aimed at financial opening during the early and late 1990s. Each of them was associated with different drivers and political and economic contexts. The beginning of the first wave in fact dates back to the early 1980s. Capital account opening was one of the final elements of a broad, gradual process of financial liberalization (Amsden and Euh 1993; Woo-Cumings 1997). Policymakers sought liberalization in light of growing evidence that Korea's financial markets were no longer adequately carrying out their intermediation function. In addition, the government wanted to extricate itself from increasingly costly commitments to privileged private interests and to avoid socializing more investment risk through the state-run financial system. Policymakers did not view capital account opening as a high priority in the liberalization efforts. They believed that the gains from opening would be relatively small and, at best, only realized in the long run. Moreover, they worried that rapid liberalization of the capital account would result in financial and macroeconomic instability. The government freed inflows first, largely to help finance current account deficits; only later, in the mid-1980s, when large inflows created monetary control problems and led to appreciation of the won, did it liberalize outflows.

However, opening up markets to foreign intermediaries had virtually no domestic support and was driven entirely by external pressure, especially by the United States. The chaebol were not ready to give up the privileges derived from the relationship between the government, the financial sector, and industry, and among them had contradictory preferences vis-à-vis financial liberalization. In addition, the government was unable to relinquish its control of the financial sector, which had been an important vehicle for industrial restructuring, due to an internal dispute between neo-liberals and developmental bureaucrats (Lim 1998). Developmental bureaucrats opposed liberalization out of fear of losing their discretionary power, whereas neo-liberals supported financial opening in the context of a wider liberalization strategy for the country (Lim 2010, 205). As a result, the relatively timid steps towards financial liberalization during the 1980s remained slow, partial, and fragmented.

The biggest leap during the first wave of capital account opening was made during the presidency of Kim Young Sam (1993-1998). In the context of a wider strategy of Segyewha (globalization), he sought to modernize – or, rather, internationalize – the country in economic terms while decreasing the role of the state as a direct financier of the private sector (Kang 2000), and to leverage international financial markets directly as a source for the Korean private sector. One way of doing this was to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in December 1996, which meant the adoption of its Code of Liberalization of Capital Movements. Together with the expansionary interests of the chaebol seeking new markets and investments abroad, the first wave of capital account opening in South Korea focused on the liberalization of capital inflows, especially short-term credit, while maintaining controls on long-term credit and equity flows.

The Kim Young Sam government's five-year financial liberalization plan announced in 1993 included capital account liberalization as a prominent item. While the authorities opened the stock market to foreigners in 1992, they maintained stiff restrictions on equity purchases, notably a 10% cap on the amount of any firm's listed stock that non-residents could hold collectively; they gradually raised this cap to 18% in 1996. In addition, policymakers did not permit non-residents to invest in most types of fixed income securities, and placed limits on the purchases that they could make, thereby maintaining a significant barrier to entry.

The basic rationale for the first wave of capital account opening was to provide the private sector in general and the chaebol in particular with access to international financial markets in order to finance their international expansion. At the same time, the chaebol took control of somewhat inexperienced non-bank financial institutions such as merchant banks, investment trusts, and insurance companies in the context of financial deregulation, thus providing them with multiple channels for tapping into foreign capital without adequate state supervision, let alone control. This, in turn, led to an investment spree in the early 1990s, when the chaebol gained autonomy from the state for their investment decisions, thus taking on higher risks.

However, the break from the previous development model was not a radical one. On the one hand, the blockage against the long-term involvement of foreign investors in the domestic financial sector was in fact consistent with the extant development model that was predicated on credit-based economic growth and an in-built bias against foreign direct investment. On the other hand, what some analysts have called a "one-sided financial liberalization policy" resulted in a particular moral hazard in the South Korean political economy during the early 1990s. While the state handed the chaebol autonomy for their economic decisions by phasing out active industrial policy and state loans, they still expected the state to come to their financial rescue if things went wrong given their preeminent position in the country's economy. This problem came to a head in the financial crisis of 1997-1998, sparked by short-term loans by foreign creditors to the Korean private sector.

As it turned out, the investment boom of the early 1990s was predicated upon inward foreign investment that consisted of around 90% of short-term portfolio flows and bank lending, often through chaebol-owned merchant banks. With the help of these institutions, the chaebol borrowed capital abroad on a short-term basis, while lending it to the chaebol sister companies on a long-term basis. The result was a huge mismatch in the maturity structure between the borrowings of the merchant banks (64% of their US$20 billion total foreign borrowings were short term) and their lendings (85% of them were long term) (Chang 1998, 1558; Chang, Park, and Yoo. 1998, 739). As a result, this system collapsed spectacularly in 1997-1998 in the context of the Asian financial crisis.

- c. The Second Wave of Capital Account Opening: The Big Bang-Approach

Out of the ashes of the economic collapse in 1997-1998 emerged the second wave of capital account liberalization in South Korea. It was the most comprehensive thus far and had the potential to completely undo the traditional development model. The Asian crisis altered the strategic calculation of the Korean policymakers. Instead of a carefully balanced approach to financial liberalization in tune with the gradual opening of the economy as a whole, the macroeconomic circumstances after the crash led to an all-out strategy to attract foreign investment at virtually any cost.

The Kim Dae Jung government, taking over in the midst of the crisis in early 1998, changed course from the chaebol-friendly approach of its predecessor by establishing a tacit alliance with foreign investors in order to move the Korean economy towards a "market democracy" more in line with U.S. style shareholder capitalism. In line with significant prodding – or, as some observers such as Joseph Stiglitz (2003) claimed, outright coercion – from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Kim Dae Jung administration applied a big bang-approach to financial liberalization, whereby the domestic financial market was comprehensively opened up to foreign investors, including equity participation and investment in the banking sector. The qualitative nature of these reform measures were clearly geared towards shifting the country from the traditional bank-centered model to a U.S.-style capital market-oriented financial system (Culpepper 2005; Mo 2008).

In return for receiving IMF emergency lending, the South Korean government had to agree to further liberalization of its capital account and greater access for foreign intermediaries. The opening proceeded in two stages. The first stage (implemented by April 1, 1999) was designed to liberalize foreign exchange transactions by corporations and financial institutions related to their external activities. To maintain a level of prudence, ex post facto reporting was required. In April 1999, the new Foreign Exchange Transaction Act replaced the positive list system with a negative list, which permitted all capital account transactions except those expressly forbidden by law and presidential decree. In the second stage (implemented by the end of 2000), the focus shifted to the liberalization of capital account transactions by individuals. A few safeguards were put in place to protect domestic financial markets from extremely unfavorable market conditions. For example, restrictions on trading the won in overseas markets by non-residents were not lifted because the authorities wanted to maintain their influence over currency movement.

Specific liberalization measures included the elimination of the ceiling on aggregate foreign ownership of listed Korean shares, the complete opening of the bond market to non-residents, allowing non-residents to purchase money market instruments, such as commercial paper, and the removal of all restrictions on foreign borrowing by Korean firms. It also permitted foreign banks and securities firms to acquire domestic entities and establish Korean subsidiaries (Kim and Yang 2010). During the capital flow boom of 2003-2007 South Korea adopted the strategy of reserve accumulation and accelerated the relaxation of outward investment controls in order to stem appreciation pressures resulting from a consistent current account surplus; this resulted in the elimination of most of the controls by 2007 (Baba and Kokenyne 2011).

As a result, by the mid-2000s the majority of controls that were in place on foreign investment within Korea and overseas investment by Korean firms and individuals prior to the Asian crisis had been eliminated. Capital account transactions involving firms, financial institutions and private individuals had been fully liberalized; tight controls on foreign land ownership had been removed; blanket ceilings on individual and total foreign equity purchases had been abolished; and restrictions on foreign investment had been partially or fully lifted with 29 categories of business (OECD 1998, and 2000; Lim and Hahm 2006). Measured in terms of formal regulations, "[t]he Korean financial market is now one of the most open for foreign investors" (Kalinowski and Cho 2009, 228).

In turn, after 1998 capital account openness quickly rose to unprecedented levels in South Korea (see graph 1). A reformist government with a neo-liberal economic agenda and allied with activists from domestic civil society and international private and public financial institutions used the proverbial window of opportunity provided by the profound economic crisis and the loss of legitimacy of the main protagonists of the traditional economic development model, the chaebol, to push through a program of comprehensive financial opening, including capital account liberalization.

However, it would be mistaken to conclude that the traditional development model – and with it, state regulation of international capital flows – had completely disappeared from the scene, giving way to the full-blown adoption of (economic) globalization, Western standards and norms in financial and corporate management, and neo-liberalism writ large. As I will explain in more detail later, the authors making such sweeping claims generally limit themselves either to the purely discursive (Hall 2003) or the formal institutional level of analysis (Moon and Rhyu 2000; Pirie 2008). What they do not consider in their analysis is the crucial difference between rhetoric and reality, i.e., how the discourse and formal institutional changes are actually implemented in the day-to-day routine in South Korea's political economy, or, in other words, what happens after the formal adoption of neoliberal norms and standards. A closer inspection of the substantive or long-term level of economic practices reveals a significant gap between the formal subscription to international norms and standards and everyday practices in South Korea's economy. As a result, financial globalization, neoliberal ideas and outside pressure have not preordained convergence towards the Anglo-American model of capitalism in South Korea (Walter 2008, 126-165; Lim 2010; Kalinowski 2013a).

- d. Capital Account Policy in Times of the Global Financial Crisis: Openness on the Outside, Barriers on the Inside

Maintaining and deepening capital account openness over the medium and long run has proven an elusive task in South Korea. After the initial adoption of capital account liberalization in the late 1990s, progress towards achieving a completely open capital account has somewhat stalled. To put it bluntly, the drive to maintain an open capital account has lost steam during the 2000s, as the Korean economy recovered fairly quickly from the Asian financial crisis and has now come to face new challenges. In fact, far from being relegated to the country's economic past, capital controls have made a comeback in the latter part of the 2000s.

Faced with a changing external environment in the context of the global financial crisis starting in 2008 and the partial rehabilitation of the chaebol, who were blamed for the outbreak of the 1990s crisis, policy-makers have resorted to a type of capital account policy that privileges the stability of the domestic economy. It especially prioritizes the maintenance of international competitiveness through a stable exchange rate and monetary policy autonomy over the goal of attracting capital inflows from abroad, given that exports account for 43% of South Korea's GDP – more than in any other advanced economy (The Wall Street Journal, November 8, 2010). As a result, the level of capital account openness somewhat decreased with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.

A defining institutional characteristic of South Korea's political economy that has enabled and legitimized the frequent use of capital account regulations during the recent past is the so-called Foreign Exchange Transaction Act. This law, established in 1961 (see above) and amended numerous times to incorporate new types of regulations, grants South Korea's financial bodies authority over foreign exchange interventions. While the Act obliges the Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF) and its counterparts, such as the Financial Supervisory Service (FSS), the Financial Services Commission (FSC), and the Bank of Korea (BOK), to accelerate the liberalization of exchange rate and related restrictions, it also allows for temporary derogations in times of instability. As a result, South Korea put in place and fine-tuned regulations on cross-border finance seven times between 2009 and 2012. In addition, the Act is exempt from the various free trade agreements that South Korea has signed in the recent past, most importantly the one with the United States.

Faced with a renewed wave of capital inflows in the second half of 2009, officials started implementing a series of measures to prevent a recurrence of the turmoil that inflicted the economy during the depths of the financial crisis a year earlier. Back then Korean banks and other financial institutions had accumulated large short-term dollar liabilities. This was partly to fund the foreign exchange hedging operations of the economy's large shipbuilding industry, and partly the result of investors engaging in the yen carry trade to buy domestic bonds. However, with the world economy experiencing rapid deleveraging and a liquidity crunch, the Korean won plummeted nearly 40% in the six months after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, and officials were forced to drain their large stockpile of reserves and seek out financial assistance from the U.S. Federal Reserve in October 2008 in the form of a US$30 billion currency swap agreement in order to stabilize the country's foreign exchange and stock markets.

As the U.S. and European central banks applied expansionary monetary policies, a new wave of capital inflows began in South Korea and other emerging markets in the second part of 2009. Officials had concerns that the hedging trading between banks and firms could again lead to an excessive increase in short-term foreign borrowing, and expose the economy to another "sudden stop" as experienced in 2008 (and in 1997). In November 2009, officials limited banks' foreign currency forward deals with exporters to prevent a repeat of the liquidity crunch at the height of the financial crisis. As the European debt crisis unfolded in 2010, European banks, which are some of the largest in Korea, began deleveraging, pushing down the won again. Additional measures to limit the size of banks' and firms' foreign currency derivatives contracts were therefore introduced in June and October 2009.

These measures prevented banks' external debt from reaching levels prior to the crisis. However, they failed to curtail total inflows, in part because the measures applied only to onshore banks and firms. Firms could still hedge their positions by selling dollars forward and buying won offshore. Offshore banks could in turn offset their position by investing in the government bond market. Korean officials therefore reintroduced withholding and capital gains taxes on purchases of government and central bank debt in January 2001, although the effectiveness of these measures has also been limited due to South Korea's large network of over seventy double taxation treaties (Pradhan et al. 2011).

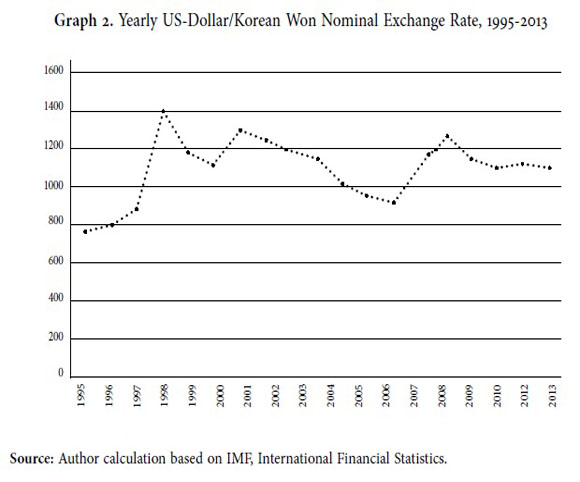

In presenting the controls, the official rhetoric sought to capitalize on and contribute to a new set of ideas that had gained support since the current crisis (Chwieroth 2014). These ideas centered on a macro-prudential regulatory philosophy aimed at limiting the build-up of systemic risk and the macroeconomic costs of financial instability. As opposed to the pre-crisis micro-prudential philosophy aimed at protecting the soundness of individual financial firms and markets, a central element of this new philosophy prioritized the deployment of counter-cyclical regulatory tools to lean against credit cycles and asset price booms (Baker 2013). Since before 2009 bond and equity flows were not subject to government regulation and given the accumulation of banks' short-term foreign debt and substantial exchange-rate appreciation (see graph 2), even a Tobin tax on portfolio flows in the bond market was considered, though ultimately rejected (interview with Joon-Ho Hahm).

Some Korean analysts, including Shin Hyun-song, a former Princeton University economist and senior adviser to then Korean President Lee Myung-bak, had framed restraints on inflows as a macro-prudential tool that could help emerging markets counter-cyclically restrict excessive inflows that tended to expand domestic credit growth and leverage, and preceded financial crises, including the one experienced in the U.S.. Advised by Shin, the government framed its measures in precisely this fashion (Tett 2011; The Economist 2010). In fact, in 2011, it introduced a tax on its banks' short-term foreign currency liabilities that it has explicitly identified as a "macro-prudential stability levy." This line of argumentation assumed greater significance in 2010, when South Korea chaired the Group of Twenty (G-20) in Seoul. During this event, the government was even able to insert a clause granting nations the right to deploy macro-prudential regulations to deter capital inflows into the Summit's communiqué.

However, what has been called "macro-prudential regulation" by official Korean and international institutions, others have termed "capital management techniques" in order to distinguish it from traditional quantity-based and permanent controls on capital inflows, such as limitations or prohibitions (Hahm; Mishkin; Shin, and Shin 2012; Baumann and Gallagher 2013; Fritz and Prates 2014). Yet, the overall result is the same: the high level of capital account openness achieved in the immediate aftermath of the 1997-1998 crisis has not been sustained over time in South Korea. Instead policymakers have become increasingly worried about the negative aspects of capital inflows in the form of exchange-rate appreciation, the loss of monetary policy independence, asset price bubbles, and high volatility (Magud; Reinhart, and Rogoff 2011). Consequently, they have resorted to restrictions on the flow of international capital into the Korean economy in order to pursue two main goals: (i) limiting financial fragility associated with capital reversals, and (ii) increasing the policy space available to exert control over key macroeconomic prices such as the exchange rate and the interest rate, mainly to enable the pursuit of countercyclical policies during booms and busts (Fritz and Prates 2014).2 In doing so, Korean officials have exhibited their traditional pragmatism in terms of financial policy: a shared mental model whereby the government deploys selective but firm regulation that does not over-regulate but sends strong signals to private sectors and markets (Leiteritz 2012).

A substantial part of the literature in comparative political economy discusses the question of whether Korea's path of economic reform after 1998 has been an unambiguous movement away from the traditional model of the development state towards some other version of contemporary capitalism represented in the Western world (Walter and Zhang 2012). In the case of capital account policy, such a movement would imply the durable institutionalization of full capital mobility at the domestic level (Thurbon and Weiss 2006). However, the Korean political economy is unlikely to adopt the unfettered flow of international capital, as is the case in both the Anglo-American and the European versions of capitalism. Though indicators of capital account openness have reached unprecedented levels in the country's history, South Korea has preserved a unique approach to capital account policy that sets it apart from the experiences and demands of industrialized countries. Restrictions on the flow of international capital remain a legitimate policy instrument in the arsenal of economic policymaking in 21st-century South Korea. The next section seeks to explain why this is the case.

2. Explaining Contemporary Capital Account Policy in South Korea

There seem to be invisible barriers or cultural templates in South Korea that limit foreign investment in general and international capital inflows in particular, despite a rather conducive legal environment. In other words, whereas the first stage of economic reforms after the Asian financial crisis points towards a stellar performance of the South Korean political economy in terms of institutional change, the second stage – where global norms and standards meet the entrenched aspects of local culture and society – is invariably more relevant when it comes to judging their sustainability over time. Here we actually observe multiple cases of "mock compliance" (Walter 2008); behind the façade of formal adoption, informal or everyday practices diverge from global norms or standards of economic policymaking. This suggests that the salience of specific institutions – formal and informal – at the domestic level acts as a prism for the structural forces of economic globalization and the pressure for institutional homogeneity associated with international capital mobility (Cortell and Davis 1996).

In my earlier work on capital account policy in Latin America (Leiteritz 2012), I have tried to combine theoretical elements from various epistemological traditions across the conventional rationalism-constructivism divide in International Relations and International Political Economy (Checkel 2012), whereby economic policymaking is the result of both material interests and domestic informal institutions, encapsulated in the term national economic identity. In this case, capital account liberalization is bound to be sustainable in a country if the material interests of specific economic sectors and the ideational context for legitimate economic policies favor international capital mobility. More specifically, if the financial sector enjoys privileged access to the political decision-making process and if domestic informal institutions emphasize international market integration over the goal of maintaining domestic stability as the fundamental social purpose of economic policy, an open capital account will be a long-term policy choice. Conversely, if the export sector dominates the financial sector in terms of political access and the informal institutional context is shaped by concerns over domestic economic stability, an open capital account over the long term is unlikely (Leiteritz 2012).

I have employed the same metric when analyzing the case of South Korea's capital account policy. First, I discuss the informal institutional context, i.e., what are considered legitimate economic policies? Here I emphasize the role of economic rationalism as a crucial domestic informal institution that acts as filter for economic policy-making. Given the indelible mark that economic nationalism as a legacy of the developmental state has left on the domestic political economy, capital account liberalization faces significant obstacles in order to become an entrenched policy in South Korea. Second, the interests of the export-oriented sector continue to dominate economic decision-making processes in the country. Given the preference of exporters for a competitive exchange rate, and especially their fear of exchange-rate appreciation, policy-makers utilize the full set of tools in order to achieve this goal, including the regulation of international capital flows. In other words, maintaining domestic macroeconomic stability and export competitiveness are the overriding objectives of economic policy-making, thus privileging the interests of exporters over those of the financial industry. As a result, capital account openness has not become "hard-wired" into South Korea's political economy.

- a. Economic Nationalism

The concept of economic nationalism refers to the expression of a constructed social identity or a set of policies that result from a shared national identity (Abdelal 2001; Helleiner and Pickel 2005; Abdelal; Herrera, Johnston, and McDermott 2009). Economic nationalism is best defined by its nationalist ontology rather than specific policy prescriptions, e.g., protectionism. It can thus be used to justify both protectionist or free-market reforms in a particular domestic setting. There are variations in both content and contestation, whereby the content of a national identity specifies a direction and a fundamental social purpose of economic policy for the country. A shared national identity lengthens the time horizon of a society and the political will necessary for economic sacrifice.

On the other hand, the concept of economic patriotism refers to "economic choices, which seek to discriminate in favour of particular social groups, firms or sectors understood by the decision-makers as insiders because of their territorial status" (Clift and Woll 2012, 308). As in the case of economic nationalism, economic patriotism can be defensive (protectionist or mercantilist) or liberal (pursuing market opening or international integration). Rather than delving into an elaborate semantic discussion about the differences between nationalism and patriotism, I treat both terms as synonymous and will henceforth use the term economic nationalism in order to describe the domestic ideational context for economic policy-making in South Korea.

Economic nationalism combines a constructivist approach from International Relations with arguments from historical institutionalism in Comparative Politics in order to explain the economic policy choices of specific countries. Whereas the varieties-of-capitalism literature, as an important part of contemporary historical institutionalism, tries to account for the formation and evolution of different economic regimes using the concepts of historical embeddedness and the path dependency of formal institutions (Hall and Soskice 2001), a constructivist approach provides an ideas-based account of the formation of national economic institutions, both formal and informal (Blyth 2002).

- Economic policy decisions can be rooted in 'representations of economic life as well as socio-cultural memories' and thus be nationalist without being about augmenting power or state-building [

] Studying the variations and evolution of economic nationalism therefore requires a careful focus on national references rather than policy content, locating analysis historically and culturally within distinctive sets of state-society relations. (Clift and Woll 2012, 313)

In the case of South Korea, national identity emphasizes a type of defensive, pure-blood nationalism (Shin 2006; Moon and Suh 2007). Given the country's long history of defending itself against various foreign invasions and occupations, usually from Japan, an "Us" versus "Them" mentality developed during the Japanese colonial period in the early 20th century, which later morphed into an ethnic nationalism. This type of nationalism was actively utilized by President Park Chung Hee to foster a sense of unity and pride in the country in order to encourage economic development and thereby transcend Korea's tragic history (Rhyu 2012).

Most visibly in the recent past, the Korean national identity manifested itself in reaction to the 1997-1998 financial crisis. On the one hand, the chaebol – propped up as "national champions" by various governments – claimed that the country was under attack from the IMF and required a collective effort to dig itself out of the crisis. Both the public and the private sector appealed to people's sense of nationalism and collective identity in order to make sacrifices, e.g., by donating gold to the country's treasury. On the other hand, a "super-committee" was formed, made up of trade unions, chaebol leaders, and the government, that produced a grand bargain over chaebol reform and labor policy reforms in just twenty days. These examples demonstrate that economic nationalism is (i) not only tied to protectionist measures, and (ii) demonstrates its main social purpose as a "highly effective social glue that can be used whenever the family heirloom starts to crack" (Tudor 2012, 266).

Similarly to other countries in East Asia where economic nationalism and a developmental mindset emerged in the aftermath of the Second World War, informal barriers to international capital mobility continue to exist in South Korea. The following description of the path taken by the original developmental state – Japan – is similar, though not identical, to that of Korea:

- Japan has formally liberalized its capital accounts but remains somewhat insulated from global financial markets due to informal barriers to capital inflows (but not outflows), such as industrial policies favoring 'national champions' or structural and cultural barriers such as weak shareholder rights, a system of cross shareholdings, and a rejection of hostile takeovers. All these aspects of Japanese capitalism not only discourage foreign direct investments, but also reduce short-term capital flows. (Kalinowski 2013b, 490)

I do not wish to suggest that the search for domestic economic stability and the subsequent application of capital controls is only possible in countries with a long history of economic nationalism. Certainly, a culture of pragmatism within the country's economic elites, the specter of past crises looming in the public's mind, and the wiggle-room conceded by international actors and trade agreements shape the ability and legitimacy of domestic policy-makers to apply regulations on cross-border financial transactions (Gallagher 2014b). However, I argue that economic nationalism provides the informal institutional foundation on which an autonomous capital account policy can be pursued. In other words, economic nationalism makes specific policies possible, though it does not cause them in any direct way (Wendt 1998; Helleiner and Pickel 2005).

To put it more generally, a state's strength of national identity shapes its foreign economic policies (Abdelal 2001; Tsygankov 2001). The stronger the identity, the more likely it is that a specific developing country will regulate international capital flows in order to preserve domestic economic stability. In order words, economic nationalism is not an indispensable factor for the application of capital controls in the first place. However, the depth and longevity of these measures depend on the strength of national identity. This, of course, is a heuristic argument which needs to be analyzed in subsequent comparative studies – an attempt that is beyond the scope of this single case study.

- The Lone Star Case

As a vignette for the heuristic value of my argument about the role of economic nationalism for foreign economic policies, I briefly discuss the Lone Star case. A remarkable level of nationalist outpouring in South Korea occurred in the context of the sale of Korean Exchange Bank (KEB) in September 2003. While the general attitude towards foreign investors and private equity funds was positive in the context of the "fire-sale period" during the late 1990s, the mood turned dramatically as the Korean economy recovered its strength in the early 2000s. As revealed later by deliberations in a judicial court, KEB was not insolvent, as was claimed by its management when the bank's shares were offered for sale. Instead, the bank's management – probably in collusion with the U.S. private equity fund Lone Star – manipulated the bank's capital adequacy ratio in order to fall below 8%, thereby circumventing the banking law that stipulated that only insolvent banks can be sold to private equity funds. In other words, the subsequent acquisition of a majority of KEB's shares by Lone Star for the bargain price of US$1.2 billion was tainted by a whiff of corruption between foreign investors and local public and private actors (Interview with Hyekyung Cho).

In addition, due to the chaebol's control over mass media, especially newspapers, criticisms of foreign investors in general and Lone Star in particular found prominent outlets. Economic nationalism reared its head and regained its strength among the public outcry over the "treacherous" foreign investors that use corruption and manipulation in order to acquire national assets. As a result, the public sentiment turned sour on foreign investors, especially private equity funds. To top it off, the U.S. private equity fund Newbridge Capital paid no tax on the US$1.2 billion profit from its sale of Korean First Bank in 2004, which it had acquired during the fire-sale period in 1999.

The government of President Roh Moo-hyun was thus called on to act vigorously against foreign "vultures" – i.e., short-term capital investors without a longer-term perspective to stay in Korea and thereby contributing to augmenting national wealth – whose behavior is deemed detrimental to the national interest. The traditional social cleavage of "Us" versus "Them" with reference to economic nationalism and anti-foreign (capital) sentiment deeply rooted in Korean society made a partial comeback in the context of the Lone Star scandal. In turn, re-regulating short-term capital flows has received social approval as a means to defend the "national interest" against foreign interests.

- b. State-Business Relations: The Political Power of the Chaebol

As I mentioned earlier, since the 1960s economic policy-making in South Korea has been profoundly shaped by the complex relationship between the state and the large conglomerates known as chaebol. The latter were propped up by the state as vanguards for fast economic growth during the military dictatorships and their democratic successor regimes from the early 1960s to the mid-1990s (Kim 1997). This symbiotic relationship unraveled in the context of the Asian financial crisis when the chaebol's reckless borrowing behavior, fostered by the process of asymmetric financial liberalization under the Kim Young Sam government, led the country to the brink of economic collapse in 1997-1998. The chaebol fell into public disrepute, being the principal target of blame for causing the crisis.

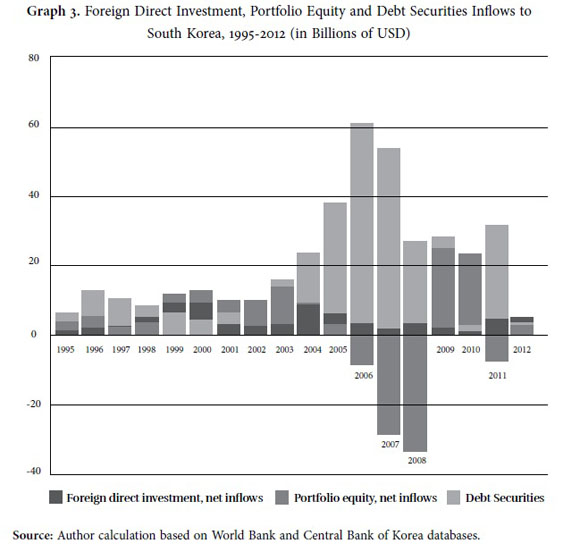

On the other hand, the Asian financial crisis gave rise to the emergence of a new actor with vested interests vis-à-vis international capital mobility: the financial service industry, now largely dominated by foreign owners. In terms of shareholder ownership, 45% of publicly listed South Korean companies are in the hands of foreigners. Almost all major Korean banks are now foreign-controlled. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has sharply increased in the years immediately after the Asian crisis (the so-called fire sale period), while reaching a plateau and henceforth slightly declining from its peak around the year 2000 – when the FDI-to-GDP ratio reached almost 4% – as the country relatively quickly recovered from the crisis (Mo 2008; see graph 3). However, there is currently a stark mismatch between inbound and outbound FDI flows: in 2012, outbound FDI amounted to US$23.6 billion and inbound FDI only to US$5 billion, i.e., the money invested in overseas markets was nearly five times higher than foreign money invested in Korea.

At any rate, state-business relations during the second half of the 2000s until the present day look different from the heydays of the Asian crisis. The chaebol have recuperated at least some of their traditional standing in the Korean economy during the last decade. In fact, their economic power began to grow back after the immediate crisis period had passed. The Korean economy continues to heavily depend on exports (around 50% of GDP in 2012) and on the large conglomerates. In 2009, the top 10 chaebol constituted 37% and the top 50 chaebol 61% of Korean exports. Samsung alone accounts for 25% of South Korea's GDP (Yoon 2013). As in the years before the 1997-1998 crisis, the chaebol have become "too big to fail". Their market power and thus their economic interests are simply too overwhelming for the government to ignore. Despite attempts to reign in their dominant position via the political agenda of "economic democratization", some analysts speak of a "second chaebol republic" when describing South Korea's contemporary political economy (Kalinowski 2009). At the same time, the financial sector's domestic expansion has stalled. In the mid-1990s, the ratio of added value created by the financial industry in the South Korean economy was in the 6% range and in 2005 it reached 6.9%. However, since the mid-2000s, the ratio has remained unchanged (Korea Joong Ang Daily 2013b).

Naturally, capital account policy is affected by this development, especially in terms of the different interests of the export-oriented and the financial industry in terms of maintaining international competitiveness (Frieden 1991). Exporters are concerned about a competitive, i.e., undervalued exchange rate to boost their income, while the financial sector is interested in international capital mobility. However, as the unfettered flow of international capital undermines the goal of exchange-rate stability, the two sectors end up on different sides when it comes to capital account policy. While exporters certainly do not argue in favor of a closed capital account and want to preserve access to foreign financing needs, they fear that massive capital inflows lead to exchange-rate appreciation and thus to declining export revenues. Exporters thus support government control of capital inflows for the sake of preventing exchange-rate appreciation and thus maintaining export competitiveness. As a result, in countries where the export sector enjoys a dominant position in the economy and therefore possesses political salience, sustainable capital account openness – the preference of the financial service industry – is unlikely.

The South Korean case is in fact an example where the export sector – concentrated in the chaebol – continues to dominate the decision-making process on capital account policy. The chaebol's entry into the financial or banking sector is officially restricted. As explained earlier, traditionally banks were controlled by the state for the provision of directed credit to the private sector. The privatization wave of the banking sector after the Asian financial crisis led to an influx of foreign investors, foreign private equity funds and commercial banks such as Citibank, taking over bankrupt domestic banks in fire sale deals. A new banking bill from May 2009 raises the ceiling of bank ownership by non-financial institutions such as the chaebol from 4 to 9%. However, the overwhelming majority of the chaebol's revenues stems from their involvement in manufacturing, not the financial industry.

To be clear, the chaebol's support for the regulation of cross-border financial transactions somewhat softened after the financial crisis during the late 1990s. This is due to the fact that they began to get involved in the carry trade for their own profit, as the interest rate differential was so lucrative. Thus, government regulations of international capital flows caused them serious material damage. As a result, one of the post financial crisis regulations included caps on forward contracts between banks and exporters relative to their export receipts (Gallagher 2014b). In sum, while exporters benefit from regulating cross-border finance in terms of curbing exchange-rate volatility, these measures can also limit their access to finance. As a result, their support for capital controls is not unambiguous.

At any rate, the primary engine of economic growth in South Korea remains the export-oriented manufacturing industry. In contrast, the financial sector only plays second fiddle to support the export sector – a legacy of the previous development model. This situation contrasts with the finance- or services-based development strategy of other East Asian "tiger" or "miracle" countries such as Singapore and Hong Kong. In the latter case, government intervention in international capital flows is anathema to the success of the chosen development model. Conversely, for the economic growth model of South Korea, a stable and competitive exchange rate is an essential policy goal of the government (Interview with Choong-Yong Ahn).

This can perhaps best be illustrated by the government's strategy to convert South Korea into an East Asian financial hub. The initiative was launched during the Roh Moo Hyun administration in January 2006 as part of the so-called East Asian business hub strategy. However, converting Seoul into another Hong Kong is incompatible with a bank-based financial system. The resulting attempt to move to a capital markets-based system might lead to a situation where the financial services industry is dominated by foreign companies – a pill too bitter for the Korean state to swallow given its focus on manufacturing for exports and the promotion of domestic firms as legacies from the developmental state period. The financial hub strategy was thus doomed to fail, as no substantial movement away from a bank-based to a market-based financial system was undertaken; therefore, the essential prerequisite for being a financial hub was missing in the first place.

In addition, a deep-seated skepticism continues to surround the opening of the domestic financial sector to foreign investors. For example, one morning President Roh Moo Hyun spoke of his desire to make the country a financial hub and destination for foreign capital. Later on that same day, the head of a large Korean bank stated that limits should be placed on foreign investment in his institution (The Wall Street Journal, July 26, 2007). The aforementioned case of Lone Star's acquisition of KEB and the subsequent trial over manipulated share prices led the state regulator, the Financial Services Commission, to prevent the U.S. private equity fund from selling its stake of KEB to foreign investors such as Singapore's DBS and HSBC until all court cases could be completed. Unsurprisingly, the chairman of KB Financial Group referred to an imbalance in growth of the financial sector as compared to the trade sector and a lack of development in nonbanking and capital markets as major challenges for the financial industry in Asia (Korea Joong Ang Daily 2013a). Thus, even in its self-perception, the financial sector recognizes its political and economic inferiority vis-à-vis the export sector.

Conclusions

In this paper, I set out to understand the political dynamics of contemporary capital account policy in South Korea. In particular, I sought to explain why capital account liberalization, in spite of substantial advances towards opening over the course of the last twenty years or so, has not been complete and sustained over time. The recent reintroduction of controls on capital inflows in the context of the global financial crisis of the late 2000s is just the latest reminder of the uneven trend of capital account policy in South Korea after the alleged end of the state-led development model upon the ashes of the Asian financial crisis in 1997-1998.

I have argued that domestic informal institutions stand in the way of a complete and sustained capital account opening process. Two factors constitute what I call national economic identity in South Korea's political economy in general, and capital account policy in particular. Economic nationalism as the ideational legacy of the developmental state model considers foreign capital, especially short-term capital flows, as inherently suspicious and potentially detrimental to national development purposes. The crucial role of large conglomerates, the chaebol, in South Korea's contemporary political economy is the material remnant of the developmental state impacting economic policy in general, and capital account policy in particular. Constituting the bulk of the country's export-oriented sector, the chaebol are keenly interested in exchange-rate stability. Given their predominant position for the success of Korea's export-based economy, their political clout is significant, in particular vis-à-vis the financial sector, the main benefactor of unfettered capital mobility. Despite attempts by the current Park Geun-hye administration to reign in their power under the slogan of "economic democratization" and efforts by the domestic and international financial industry to assert itself, the country's economic wellbeing is inextricably linked to the success of the chaebol's business strategy. As a result, capital account policy will (need to) continue to serve the main interests of these companies, while preserving a degree of autonomy for the government to entertain measures for the sake of macroeconomic stability that do not correspond to the particular interests of the export-oriented sector.

Many observers have claimed that the developmental state model disappeared with the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. Indeed, South Korea's political economy has undergone dramatic changes at the formal institutional level towards increased opening since 1997, which, in turn, form the basis for the claim that the developmental state has disappeared. However, I have emphasized the need to focus on the informal institutional level, where the legacies of the developmental state are still visible today. Looking only at formal changes in order to postulate the end of the developmental state risks ignoring its informal yet powerful residues in contemporary South Korea. As a result, the reports of the death of the developmental state are, at best, short-sighted and, at worst, greatly exaggerated.

Export-oriented developing countries, better known as emerging markets, continue to have the ability to preserve significant room to manoeuvre in terms of economic policy despite global trends and pressure towards liberalization. Yet, in order to unearth this considerable policy space, the academic literature in international political economy needs to look beyond formal domestic institutions. This paper has shown that the crucial factors for explaining the divergence from global monetary norms lie at the informal level of domestic policy-making in various parts of the developing world (Leiteritz 2012; Gallagher 2014a). However, additional empirical, comparative studies involving a wider range of emerging economies are needed in order to corroborate the findings from this single case study.

Comments

* This paper is the result of a six-month research stay in Seoul in 2013. I am grateful to the Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies (KFAS) for financial support, to the two anonymous reviewers of Colombia Internacional for their helpful comments on a first draft of the article, and to María Paz Berger for her excellent research assistance.

1 During the high-growth period in the 1970s, a critical shift occurred when the state mandated and fostered the movement from labor-intensive to capital-intensive industries such as chemicals, cars, shipbuilding, computers, etc. (Haggard 1990, 51-75).

2 However, the record of capital management techniques to effectively deal with the four negative implications of capital inflows is rather mixed (Baumann and Gallagher 2013).

References

1. Abdelal, Rawi. 2001. National Purpose in the World Economy. Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

2. Abdelal, Rawi, Yoshiko M. Herrera, Alastair Iain Johnston, and Rose McDermott. 2009. Identity as a Variable. In Measuring Identity. A Guide for Social Scientists, eds. Rawi Abdelal, Yoshiko M. Herrera, Alastair Iain Johnston, and Rose McDermott, 17-32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

3. Amsden, Alice H. 1989. Asia's Next Giant. South Korea and Late Industrialization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

4. Amsden, Alice H. and Yoon-Dae Euh. 1993. South Korea's 1980s Financial Reforms: Good-bye Financial Repression (Maybe), Hello New Institutional Restrains. World Development 21 (3): 379-390. [ Links ]

5. Baba, Chikako and Annamaria Kokenyne. 2011. Effectiveness of Capital Controls in Selected Emerging Markets in the 2000s. IMF Working Paper 11/281. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [ Links ]

6. Baker, Andrew. 2013. The New Political Economy of the Macroprudential Ideational Shift. New Political Economy 18 (1): 112-139. [ Links ]

7. Baumann, Britany A. and Kevin P. Gallagher. 2013. Post-Crisis Capital Account Regulation in South Korea and South Africa. Working Paper N. 320, Political Economy Research Institute. Amherst: University of Massachusetts. [ Links ]

8. Blyth, Mark. 2002. Great Transformations. Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

9. Chang, Ha-Joon. 1998. Korea: The Misunderstood Crisis. World Development 26 (8): 1555-1561. [ Links ]

10. Chang, Ha-Joon, Hong-Jae Park, and Chul Gyue Yoo. 1998. Interpreting the Korean Crisis: Financial Liberalization, Industrial Policy and Corporate Governance. Cambridge Journal of Economics 22 (6): 735-746. [ Links ]

11. Checkel, Jeffrey T. 2012. Theoretical Pluralism in IR: Possibilities and Limits. In Handbook of International Relations, eds. Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse, and Beth A. Simmons, 220-242. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

12. Cho, Yoon Je. 1989. Finance and Development: The Korean Approach. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 5 (4): 88-102. [ Links ]

13. Chwieroth, Jeffrey M. 2014. Managing and Transforming Policy Stigmas in International Finance: Emerging Markets and Controlling Capital Inflows after the Crisis. Review of International Political Economy (Forthcoming). [ Links ]

14. Clift, Ben and Cornelia Woll. 2012. Economic Patriotism: Reinventing Control over Open Markets. Journal of European Public Policy 19 (3): 307-323. [ Links ]

15. Cortell, Andrew P. and James W. Davis, Jr. 1996. How Do International Institutions Matter? The Domestic Impact of International Rules and Norms. International Studies Quarterly 40 (4): 451-478. [ Links ]

16. Culpepper, Pepper D. 2005. Institutional Change in Contemporary Capitalism. World Politics 57 (2): 173-199. [ Links ]

17. The Economist. 2010. South Korea's Currency Controls: The Won that Got Away. 16 June. [Online] http://www.economist.com/blogs/newsbook/2010/06/south_koreas_currency_control [ Links ]

18. Evans, Peter. 1995. Embedded Autonomy. States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

19. Frieden, Jeffry A. 1991. Invested Interests: The Politics of National Economic Policies in a World of Global Finance. International Organization 45 (4): 425-451. [ Links ]

20. Fritz, Barbara and Daniela Prates. 2014. The New IMF Approach to Capital Account Management and Its Blind Spots. Lessons from Brazil and South Korea. International Review of Applied Economics 28 (2): 210-239. [ Links ]

21. Gallagher, Kevin P. 2014a. Ruling Capital. Emerging Markets and the Reregulation of Cross-Border Finance. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

22. Gallagher, Kevin P. 2014b. Countervailing Monetary Power: Re-Regulating Capital Flows in Brazil and South Korea. Review of International Political Economy (Forthcoming). [ Links ]

23. Haggard, Stephan. 1990. Pathways from the Periphery: The Politics of Growth in the Newly Industrializing Countries. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

24. Hahm, Joon-Ho, Frederic S. Mishkin, Hyung Song Shin, and Kwanho Shin. 2012. Macroprudential Policies in Open Emerging Economies. NBER Working Paper No. 17780. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

25. Hall, Rodney Bruce. 2003. The Discursive Demolition of the Asian Development Model. International Studies Quarterly 47 (1): 71-99. [ Links ]

26. Hall, Peter A. and David Soskice (Eds.). 2001. Varieties of Capitalism. The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

27. Helleiner, Eric and Andreas Pickel (Eds.). 2005. Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

28. Hundt, David. 2009. Korea's Developmental Alliance. State, Capital, and the Politics of Rapid Development. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

29. International Monetary Fund. International Financial Statistics. Various years. Washington, D.C.: IMF. [ Links ]

30. Kalinowski, Thomas. 2013a. Crisis Management and the Varieties of Capitalism. Fiscal Stimulus Packages and the Transformation of East Asian State-Led Capitalism since 2008. Discussion Paper SP III 2013-501. Berlin: Social Science Research Center. [ Links ]

31. Kalinowski, Thomas. 2013b. Regulating International Finance and the Diversity of Capitalism. Socio-Economic Review 11 (3): 471-496. [ Links ]

32. Kalinowski, Thomas. 2009. The Politics of Market Reforms: Korea's Path from Chaebol Republic to Market Democracy and Back. Contemporary Politics 15 (3): 287-304. [ Links ]

33. Kalinowski, Thomas and Hyekyung Cho. 2009. The Political Economy of Financial Liberalization in South Korea: State, Big Business and Foreign Investors. Asian Survey 49 (2): 221-242. [ Links ]

34. Kang, C. S. Elliot. 2000. Segyehwa Reform of the South Korean Developmental State. In Korea's Globalization, ed. Samuel S. Kim, 76-101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

35. Kang, David C. 2002. Bad Loans to Good Friends: Money Politics and the Developmental State in South Korea. International Organization 56 (1): 177-207. [ Links ]

36. Karcher, Sebastian and David A. Steinberg. 2013. Assessing the Causes of Capital Account Liberalization: How Measurement Matters. International Studies Quarterly 57 (1): 128-137. [ Links ]

37. Kim, Eun Mee. 1997. Big Business, Strong State: Collusion and Conflict in South Korean Developments, 1960-1990. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

38. Kim, Soyoung and Doo Yong Yang. 2010. Managing Capital Flows. The Case of the Republic of Korea. In Managing Capital Flows. The Search for a Framework, eds. Masahiro Kawai and Mario B. Lamberte, 280-304. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar and Asian Development Bank Institute. [ Links ]

39. Korea Joong Ang Daily. 2013a. KB Chief Worrying about Outflows. May 10. [Online ] http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2971345 [ Links ]

40. Korea Joong Ang Daily. 2013b. Shin Pushes Bankers on Added Value. May 25-26. [Online] http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2972109 [ Links ]

41. Leiteritz, Ralf J. 2012. National Economic Identity and Capital Mobility: State-Business Relations in Latin America. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [ Links ]

42. Lim, Timothy C. 1998. Power, Capitalism, and the Authoritarian State in South Korea. Journal of Contemporary Asia 28 (4): 457-483. [ Links ]

43. Lim, Haeran. 2010. The Transformation of the Developmental State and Economic Reform in Korea. Journal of Contemporary Asia 40 (2): 188-210. [ Links ]

44. Lim, Wonhyuk and Joon-Ho Hahm. 2006. Turning a Crisis into an Opportunity: The Political Economy of Korea's Financial Sector Reform. In From Crisis to Opportunity: Financial Globalization and East Asian Capitalism, eds. Jongryn Mo and Daniel I. Okimoto, 83-119. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. [ Links ]

45. Magud, Nicolás E., Carmen M. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2011. Capital Controls: Myth and Reality. A Portfolio Balance Approach. NBER Working Paper 16805. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

46. Mo, Jongryn. 2008. The Korean Economic System: Ten Years after the Crisis. In Crisis as Catalyst: Asia's Dynamic Political Economy, eds. by Andrew Macintyre, T.J. Pempel, and John Ravenhill, 251-270. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

47. Moon, Chung-In. 1999. Democratization and Globalization as Ideological and Political Foundations of Economic Policy. In Democracy and the Korean Economy, eds. Jongryn Mo and Chung-In Moon, 1-33. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. [ Links ]

48. Moon-Chung-in and Sang-Young Rhyu. 2000. The State, Structural Rigidity, and the End of Asian Capitalism: A Comparative Study of Japan and South Korea. In Politics and Markets in the Wake of the Asian Crisis, eds. Richard Robinson and Hyuk-Rae Kim, 77-98. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

49. Moon, Chung-in and Seung-Won Suh. 2007. Burdens of the Past: Overcoming History, the Politics of Identity and Nationalism in Asia. Global Asia 2 (1): 32-48. [ Links ]

50. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2000. Economic Survey of Korea. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [ Links ]

51. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 1998. Economic Survey of Korea. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [ Links ]

52. Onis, Ziya. 1991. The Logic of the Developmental State. Comparative Politics 24 (1): 109-126. [ Links ]

53. Pirie, Iain. 2008. The Korean Developmental State: From Dirigisme to Neo-Liberalism. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

54. Pradhan, Mahmood, Ravi Balakrishnan, Reza Baqir, Geoffrey Heenan, Sylwia Nowak, Ceyda Oner, and Sanjaya Panth. 2011. Policy Reponses to Capital Flows in Emerging Markets. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/10. Washington: IMF. [ Links ]

55. Rhyu, Sang-young. 2012. The Spirit of Korean Development. Center for International Studies, Yonsei Graduate School of International Studies and Presidential Council on Nation Branding. [ Links ]

56. Shin, Gi-Wook. 2006. Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

57. Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2003. Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

58. Tett, Gillian. 2011. New Ways to Control Hot Money Bubbles. Financial Times. January 13. [Online] http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8bfc81e2-1f30-11e0-8c1c-00144feab49a.html#axzz3FQ6IKebz [ Links ]

59. Thurbon, Elizabeth and Linda Weiss. 2006. Investing in Openness: The Evolution of FDI Strategy in South Korea and Taiwan. New Political Economy 11 (1): 1-22. [ Links ]

60. Tsygankov, Andrei P. 2001. Pathways after Empire. National Identity and Foreign Economic Policy in the Post-Soviet World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

61. Tudor, Daniel. 2012. Korea: The Impossible Country. Tokyo, Rutland and Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. [ Links ]

62. Wade, Robert. 1990. Governing the Market. Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

63. The Wall Street Journal. 2010. The Miracle Is Over. Now What? November 8. [Online] http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704791004575519703277433756 [ Links ]

64. The Wall Street Journal. 2007. Korea's Mixed Signals May Keep Foreign Investors from Diving in. July 26. [Online] http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB118538295410577725 [ Links ]

65. Walter, Andrew. 2008. Governing Finance. East Asia's Adoption of International Standards. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

66. Walter, Andrew and Xiaoke Zhang. 2012. Debating East Asian Capitalism: Issues and Themes. In East Asian Capitalism. Diversity, Continuity, and Change, eds. Andrew Walter and Xiaoke Zhang, 3-25. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

67. Wendt, Alexander. 1998. On Constitution and Causation in International Relations. Review of International Studies 24 (5): 101-118. [ Links ]

68. Wong, Joseph. 2004. The Adaptive Developmental State in East Asia. Journal of East Asian Studies 4 (3): 345-362. [ Links ]

69. Woo, Jung-en. 1991. Race to the Swift. State and Finance in Korean Industrialization. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

70. Woo-Cumings, Meredith (Ed.). 1999. The Developmental State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

71. Woo-Cumings, Meredith. 1997. Slouching toward the Market: The Politics of Financial Liberalization in South Korea. In Capital Ungoverned. Liberalizing Finance in Interventionist States, Michael Loriaux, Meredith Woo-Cumings, Kent E. Calder, Sofia Perez, and Sylvia Maxfield, 57-91. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 57-91. [ Links ]

72. Yoon, Dae-yeob. 2013. The End of Korean Model? The Politics of Export-Led Development after the 1997 Financial Crisis. Presentation given at ISEF Seminar. Seoul: Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies. [ Links ]

Interviews

73. Choong-Yong Ahn, Foreign Investment Ombudsman, June 4, 2013. [ Links ]

74. Hyekyung Cho, former staff member of Banking Trade Union, June 5, 2013. [ Links ]

75. Joon-Ho Hahm, Professor of International Economics and Finance, Yonsei University, March 12, 2013. [ Links ]

RECEIVED: February 10, 2014 ACCEPTED: July 23, 2014 REVISED: September 12, 2014