Introduction

How does electoral competition shape campaign finance rules? Uncovering this relationship is vital for our understanding of the role of money in democratic politics. Yet existing political economy literature overlooks the linkage between electoral incentives and political finance regulation. Only recently some scholars have paid attention to important issues like the effects of fund parity for electoral competition (Potter and Tavits 2015), the effect of incentives for personal vote on political finance regulation (Samuels 2001a, 2001b, 2001c, 2001d, 2002), or the cost of elections in contexts where electoral uncertainty is high (Chang 2005; Chang and Golden 2007). This article reveals unknown facets of electoral competition and their consequences for campaign finance regulation.

Building on these seminal contributions, this article examines whether the level of electoral volatility affects the nature of campaign finance reforms in Colombia. In particular It argues that, in highly contested electoral environments, getting elected or re-elected is more expensive (Chang 2005; Chang and Golden 2007), and consequently, political parties have strong incentives to continually change political finance rules in order to guarantee a continuous flow of money into the electoral campaigns. In the particular case of Colombia, political parties responded to high levels of electoral volatility (and fragmentation) by reforming campaign finance rules, thereby transforming into a cartel party model of political financing.

While previous research studies the main characteristics of political finance regulations across the world (Scarrow 2007; Nassmacher 2009; Norris and Van Es 2016), only few specialists have systematically investigated the relationship between electoral competition and political finance regulation (Biezen and Rashkova 2014; Potter and Tavits 2015; Kölln 2016). This article contributes to this debate by providing empirical evidence that electoral volatility triggers frictions between dominant and minor parties around the distribution of resources available for electoral competition and provides incentives for toughening political finance regulation. In line with Scarrow’s theory of party interests as determinants of political finance reforms (Scarrow 2004), this article argues that political finance rules emerge as the result of a “tension” between parties interested in increasing their income as an end itself (revenue-maximizing parties) and parties interested in increasing their income as a way to ensure electoral victory or create short-term electoral advantages (vote-maximizing parties).

Following Scarrow’s point that parties’ interests “generate differing expectations about how parties will approach negotiations over party finance reforms” (Scarrow 2004, 656), this study finds evidence that increasing electoral volatility in Colombia made dominant parties more sensitive to financial circumstances and more willing to restrict access to private donations, expanding public subsidies that would be distributed proportionally by previous electoral performance. As a consequence of these changes, in the short term, newcomers would have access to public resources and could compete in local and regional elections; but in the long term, dominant parties consolidated their position as the main recipients of public subsidies and reduced the level of electoral volatility.

In summary, this text shows that increasing electoral volatility imposes significant financial pressures on political parties, increases their “cartel-like” behavior (Katz and Mair 1995, 2009), and makes them more willing to favor “revenue-maximizing” party finance reforms. In line with Koß’s work on party funding regimes in Western Europe (Koß 2010), this article offers new empirical evidence about the conditions under which cartel parties would support more or less equitable public funding schemes (Scarrow 2006) or campaign finance rules to promote higher fund parity (Potter and Tavits 2015). In particular, it shows evidence that cartel parties use party finance reforms as key devices to boost their revenues and exclude new challengers from the electoral arena.

This argument has important implications for the literature on electoral engineering and the scholarship on transparency and corruption. While electoral incentives have received considerable attention as possible causes of political corruption (Rose-Ackerman 1999; Chang, 2005; Kunicova 2006; Chang and Golden 2007; Fisman and Golden 2017), the causal mechanisms that link political incentives and behavior have received less attention, and there is only partial empirical evidence of their relevance for party finance rules. The links between political financing and political corruption are so evident that we “cannot reasonably expect to tackle corruption if [we] turn a blind eye to the issue of political funding” (Pinto-Duschinsky 2002, 84). Therefore, political corruption is not only amenable to changes in electoral rules; reforms of party finance regulations could be beneficial as well.

This article is organized as follows. Section 1 discusses the theoretical framework. Section 2 describes the main characteristics of the political finance system in Colombia. This section focuses on the most recent evolution of Colombian party finance law. Section 3 explores the relationship between electoral volatility and party finance reforms in Colombia. Finally, section 4 offers some concluding remarks.

1.Electoral Systems and Political Finance Regulation

The study of the relationship between electoral systems and political financing is usually over-looked as a field of research in comparative politics (Grofman 2006, 2016; Herron et al. 2018). While there have been significant efforts to describe the global patterns of political finance regulation (Del Castillo and Zovatto 1998; Pinto-Duschinsky 2002; Zovatto 2003; Malamud and Posada-Carbó 2005; Casas-Zamora 2005; Burnell and Ware 2006; Falguera et al. 2014; Norris and Van Es 2016), only few of these works provide acute insights to understand them (Scarrow 2007, 196), to disentangle the political conflicts behind their design and implementation, or simply to evaluate their impact on electoral competition.

The literature on political finance mainly focuses on how electoral incentives to cultivate personal reputation make money more important for electoral success, trigger more campaign spending, and encourage corruption and clientelistic practices (Cox and Thies 2000; Samuels 2001a, 2001c; Pinto-Duschinsky 2002; Chang and Golden 2007; Kselman 2011; Gingerich 2013; Golden and Mahdavi 2015; Fisman and Golden 2017; Johnson 2018). These studies also show that campaigning becomes more expensive in democracies where electoral competition is more intense.1

In particular, several studies demonstrate that preferential-list proportional-representation electoral systems provide strong incentives for politicians to cultivate personal vote (Carey and Shugart 1995; Crisp et al. 2007) and make inter-party and intra-party electoral competition more intense (Shugart 2005; Colomer 2011). Consequently, candidates are forced to increase their campaign spending in order to assure their electoral success. In other words, political finance literature has extensively shown that, ceteris paribus, the essential features of the electoral rules shape the way voters assess candidates, provide incentives for politicians to design their campaign styles according to voters’ modes of evaluation, and boost the cost of campaigning (Gingerich 2009, 2013).

The literature on comparative electoral systems also illustrates the potential effects of volatility and proportionality on politicians’ financial needs. For example, some researchers show that candidates in Brazilian legislative elections (an open-list PR electoral system) require large amounts of campaign spending to promote personal reputation (Ames 1995, 2001). As competition intensifies, candidates need larger amounts of campaign money because they need to spend more in order to distinguish themselves from others (Samuels 2001b). Consequently, Brazilian elections are not only more competitive (more parties and candidates compete for a relatively stable number of political positions) but also more expensive (Samuels 2001c; Mancuso et al. 2016), and the candidates’ likelihood of winning strongly depends on raising more donations than their opponents (Abramo 2014b; Boas et al. 2014; Mancuso et al. 2016).

Similarly, studies of Japanese elections find that the demand for campaign funding in Japan increases as the degree of political competitiveness grows (Cox and Thies 1998, 2000). In fact, there is evidence that the singular, non-transferable vote (SNTV) electoral system in Japan makes intra-party competition more intense, increases individual candidates’ expenditures, and creates constant incentives for politicians to raise more money and outmatch other candidates’ spending. Put et al. (2015) found similar results for the case of legislative elections in Belgium (another proportional representation electoral system).

In short, electoral systems scholars show that higher levels of electoral competition increase the pressure on politicians to raise money, find new donors, and spend more money in campaigning. They also show that these pressures are even higher in candidate-centric electoral systems. In contexts of exacerbated electoral competition, politicians’ need for campaign money and their preferences about campaign finance rules are a function of the degree of inter-party and intra-party electoral competition. From this point of view, higher electoral competition and increasing uncertainty provide incentives for politicians to implement “service-induced” party finance (Samuels 2001a) and electoral transparency rules (Berliner and Erlich 2015).

In her seminal work on campaign finance reform, Scarrow (2004, 669) argues that the prevailing patterns of electoral competition affect the debates over party finance, and ultimately, shape party finance rules. She contends that political parties could have different interest regarding political finance regulation (Scarrow 2004, 655). On the one hand, “revenue-maximizing” parties are interested in increasing their income beyond what they need for campaigns and use it to consolidate their organizations. In contrast, other parties may privilege their “electoral-economy” goals in which money is useful only if it creates short-term electoral advantages.

Unsurprisingly, “revenue-maximizing” parties will favor party finance rules that increase their revenues and limit party competition (Koß 2010). As predicted by the cartel party theory (Katz and Mair 1995, 2009), dominant parties will collude to create political finance schemes that boost their revenues (Scarrow 2004, 656). Meanwhile, when short-term electoral goals prevail over long-term organizational goals, political parties will favor political finance rules that increase their electoral advantages over their competitors (e.g. rising entry barriers for new-comers or opposing the expansion of public finance schemes). According to Scarrow (2004), the former situation is more common where electoral fragmentation is higher, while the latter situation is more common where two-party competition is strongest and where is easiest for parties to claim credit for policies (Scarrow 2004, 659).

This article shows that the most recent pattern of political competition in Colombia fits the “revenue-maximizing” or ‘cartel’ model, in which dominant parties cooperate to maximize their revenues, increase public subsidies, and reduce the importance of individual donors (at least, formally). Increasing electoral volatility encouraged parties to cooperate on the adoption of more restrictive campaign finance rules, the expansion of public subsidies, and the reduction of fund parity. The recent expansion of direct and indirect public subsidies in Colombia is clearly biased in favor of dominant parties and has effectively frozen out new challengers. Unsurprisingly, the effective number of parties is now more stable. But, as the intensity of party finance regulation increases, electoral competition is less uncertain and the state becomes the main source of financial support for dominant political parties (Biezen and Rashkova 2014, 891).

However, unlike the Western European democracies described by Biezen and Rashkova (2014), the influence of private donors in Colombia persists because the monitoring or sanctioning mechanisms do not work properly. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that the Colombian EMB (Electoral Management Body) has neither technical capacity nor political will to effectively enforce limits on donations or campaign spending (Londoño 2018).

Therefore, party finance rules in Colombia operate as a dual system in which outsider parties rely on small or illegal donors, while insider (cartel) parties rely on state funding. That is, political parties become rent-seekers and private interests groups continue being better represented in the policymaking process than less-organized citizens.

The following sections presents some empirical evidence to support this working hypothesis. Section 3 briefly describes the evolution of party finance rules in Colombia since 1985. This section shows that party finance reforms in the 1990s clearly sought to increase the amount resources available for newcomers and small parties. However, cartel parties seem to be a dominant force in party finance reform since 2003. Section 4 argues that the recent evolution towards a revenue-maximizing model in party finance is highly correlated with increasing electoral volatility and it has had important consequences for the level of electoral fragmentation.

2. Party finance reform in Colombia

Political finance regulation in Colombia is a complex system of rules that has been sequentially developed since 1985 (MOE 2016; Londoño 2018). The 1985 Political Parties Law (Law 58/1985) and the 1991 Constitution provided a general framework for political financing in Colombia. The 1985 Political Parties Law formalized common practices and mainly focused on the regulation of private donations to political parties. Most of the provisions were intended to limit private donations and campaign spending, and create an EMB for monitoring and enforcement (Londoño 2018, 32).

The 1991 Constitution added some public funding provisions to the basic framework established in 1985 (MOE 2016). As part of a process of promoting political inclusion and democratization, the new constitution established a new scheme of direct and indirect public subsidies to political parties, free or subsidized airtime in the media (TV and radio), and new resources to strengthen the EMB’s capacity to monitor and oversight (Londoño 2018, 33).

The subsequent reforms did not radically change the general structure of the model of political financing. They only adjusted the new regulations (e.g. new public funding schemes) to the course of party competition or the consequences of several scandals of illegal donations to electoral campaigns. Table 1 summarizes the main changes adopted since 1991.

Based on Table 1, one could describe the distinctive features of party finance rules in Colombia as follows: i) public subsidies are more abundant and favor electoral performance rather than political equality (Londoño 2018, 34, 70); ii) there are substantial restrictions on individual donations and a little fewer on corporate donations; iii) campaign spending limits are regularly defined by the EMB, but they are barely enforced; and iv) monitoring and oversight mechanisms are well conceived but poorly executed. In other words, the political finance model in Colombia mainly relies on public funds (Joignant 2013, 176), favors dominant rather than minor parties, and does not guarantee transparency regarding private donations.

Table 1 Party Finance Reforms in Colombia since 1991

| Year | Reform | Main changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Law 130 | Different rules for presidential, legislative, and local elections. 5% (valid votes) threshold to receive subsidies. Low cost loans to parties (regulated by the Central Bank). |

| 2003 | Statutory Act 01 | More budget for direct and indirect public funding to parties |

| 2005 | Law 996 | Ley de Garantias to introduce check-and-balance mechanisms after the approval of presidential reelection. Introduction of 10% ex-ante direct subsidies (“anticipos”) More limits to private donations (including corporate donations) 4% (valid votes) threshold to receive direct subsidies. More public funding and free access to media. |

| 2009 | Statutory Act 01 | Ban on donations from foreign interests and illegal activities. Higher threshold for ongoing party funding (from 2% to 3% votes legislative elections). |

| 2011 | Law 1474 | Anti-corruption Act: private donors cannot participate in the public procurement process if they donated more than 2.5% of total donations to any candidates in the previous elections. |

| 2011 | Law 1475 | More generous ex-ante subsidies for all parties (up to 80% of spending caps). Limits on individual donations (up to 10% of total private donations). Campaign spending caps defined by the EMB. Ban on anonymous donations and donations from foreign interests and illegal activities. Campaign expenditures administrated from a unique, registered bank account. |

| 2017 | Law 1864 | New sanctions for violations of political finance regulations. |

Source: MOE 2016; Londoño 2018.

Public subsidies have risen from about US$ 7 million in 2004 to US$ 12 million in 2016, while the number of recipients has fallen from 72 parties in 2004 to 13 parties in 2016 (Londoño 2018, 72). However, the main source of public funding for political parties are not these direct subsidies but the reimbursements of election expenses (pagos por reposición). These reimbursements are paid to political parties for every valid vote each received in the previous elections. These reimbursements amounted to about US$26 million in 2012, US$ 28 million in 2014, and US$ 21 million in 2016 (Londoño 2018, 90-94).2

The data show that Colombian political parties are more dependent on public funds than private donations. For example, about half of the operational costs of the main left-wing party (Polo Democrático) and the main right-wing party (Centro Democrático) in 2015 were paid with public funds (Londoño, 2018, 75). According to Londoño (2018, 75), if one adds ongoing direct subsidies and reimbursements (the so-called pagos por reposición), in 2012 public funding represented 92% of the Liberal Party’s total income, 73% of the Conservative Party’s total income, 85% of the Partido de la U ’s total income, 76% of the Green Party’s total income, and 76% of the Polo Democrático’s total income. Obviously, the increase in public funding of parties has had important budgetary effects. For example, Londoño (2018, 99-101) estimates that the budget allocation to fund political parties almost doubled between 2012 (US$ 40 million) and 2014 (US$ 72 million).

Meanwhile, the role of private donors in Colombia is rather unknown. Formal political financing rules seems to limit their role in funding electoral campaigns. However, monitoring or sanctioning mechanisms are structurally weak and the incentives to break such formal rules are strong. The lack of data, the vagueness of some private finance mechanisms, and politicians’ lack of willingness to report private donations make it even harder to fathom the situation.

Londoño (2018 188-189) estimates that politicians raised about US$ 68 million from private donors in the 2014 legislative elections. However, almost half corresponded to loans that were reimbursed to the candidates as part of their election expenses (pagos por reposición). The available reports also indicate that political parties only raised private donations of around US$11 million in 2016 (Londoño 2018, 110). In any case, more precise figures are unavailable and the real impact of private donations in Colombian elections remains a mistery.

Every year, the EMB sets spending limits for all political parties participating in electoral contests. These legal limits are based on statistical estimations of the cost of campaigning (the so-called índice de costos de campaña), the electoral census, and the budget provisions available for elections. Official reports indicate that political parties comply with these spending caps. However, several independent investigations suggest that politicians do not really comply with the limits set by the EMB (Saavedra 2017; Londoño 2018). For example, Saavedra (2017, 2-3), shows that, although the EMB set a spending limit of about US$ 275,000 for the 2014 legislative elections, the average costs of congressional campaigns that year was over US$ 1 million, almost four times the legal ceiling. Candidates rarely report the total amount of actual expenditures and the EMB does not have any formal or informal mechanisms to make them comply.

This takes us to one of the main features of the Colombian political finance system: the EMB lacks political independence and institutional capacity to enforce transparency rules. First of all, the EMB suffers from the same illnesses of other Colombian high courts: appointment, tenure, and removal mechanisms of electoral judges make their careers quite dependent on politicians’ needs and less powerful as monitoring/sanctioning actors. The EMB appointment procedures are under the control of Congress and its composition mirrors the partisan structure of the legislative branch of government (Londoño 2018).

And second, the EMB does not have technical capacity to exercise effective oversight of the financial reporting from political parties or impose sanctions on candidates or parties that do not comply with the electoral law. In fact, most of the sanctions for violations of the electoral law have been imposed by the State Council rather than the EMB (Londoño 2018, 146). In any case, there is a generalized lack of control on how money is raised, managed, and spent.

Correcting those flaws was one of the central features of the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerilla. As a result of the negotiation, the government established an independent Special Electoral Reform Commission (Misión Electoral Especial) to propose substantial reforms to the electoral system (MEE 2017). The main focus of the proposals was to tackle some of the issues described above.

The commission’s proposal sought to improve political inclusion, fix some of the party finance issues, and introduce significant changes to the EMB. The commission also proposed important changes to the electoral system (e.g. a transition from a PR-Open List to a PR-Closed List system). The commission’s report also proposed increasing public funding for candidates and parties, toughening limits on private donations, and creating a whole new electoral management institutional architecture (MEE 2017). All these proposals were discussed and rejected by Congress in December 2017.

The legislative debate about the MEE’s proposals illustrates the fact that both politicians and experts share similar visions regarding party finance in Colombia. In a context of increasing campaign costs, all (successful and failed) electoral reforms since 2003 aim to reduce the number of political parties participating in electoral contests and facilitating the flow of public funds towards electoral campaigns.

As mentioned above, direct and indirect public funding has increased substantially over the past two decades. Since the allocation of subsidies and free airtime is usually proportional to previous electoral performance, the distribution of these resources clearly favors dominant political parties and hinders newcomers and small parties. The implementation of higher thresholds of access to public subsidies and free airtime also favors dominant parties.

Additionally, new transparency rules do not really promote public disclosure or proper identification of donors. The EMB has been designed as a highly politicized and toothless institution. Like in other countries in Latin America, stricter formal rules on accountability and transparency seem to be the result of politicians’ self-interested effort to instill some sense of trust in the campaign financing system or even rationalize campaign funding to avoid abuses from local brokers (Speck 2016) rather than putting efficient transparency mechanisms into operation.

In other words, the most recent party finance reforms transformed Colombian parties into cartel parties. As Katz and Mair (1995, 2009) have noted about some Western European party systems, Colombian parties have increasingly weak linkages with the civil society and an over-reliant relationship with the state. Their membership rates are very low, their capacity to mobilize the public is limited, their level of institutionalization is rather poor, and their capacity to raise campaign funds among citizens or groups of citizens is extremely low. Consequently, they mostly rely on corporate donations and public subsidies, and thus politicians are less responsive to citizens’ needs and more responsive to special interest groups and bureaucratic networks.

Biezen and Kopeckỳ (2014) broaden the analysis of Katz and Mair (1995) and argue that the emergence of cartel parties in Europe has three dimensions: the dependence of parties on the state subventions, the increasing regulation of parties by the state, and the capture of the state by parties (party patronage). The Colombian party system fits the description quite well.

First, the parties are more financially dependent on state subventions and less dependent on membership contributions or grassroots funding. State subventions are be-coming more important than private donations. Even more important, the public funding system privileges dominant rather than minor parties.

Second, political parties as organizations are becoming increasingly regulated or shaped by the state. In exchange for increasing public subsidies, political parties face increasing regulation of their internal voting and selection procedures, their admission requirements, and their internal democracy mechanisms.

And finally, once elected, parties have privileged access to the state and use it to distribute public jobs and contracts, which is the only way to keep minimal partisan bases at the local level and some fluid relationships with their private donors.

3. From vote seeking to revenue-maximizing parties?

Albarracín et al. (2018) carefully describe the process of de-institutionalization of the party system in Colombia. As a consequence of economic and demographic changes, profound institutional reforms, and public security crises, Colombian politicians have less incentives to join and remain loyal to political parties, while political parties have less organizational capacity and their brands are less appealing or meaningful to voters. Given the lack of programmatic agendas, clientelistic bonds between voters and politicians are predominant. The whole party system underwent a drastic decrease in institutionalization (Albarracín et al. 2018).

The changing nature of the party system in Colombia is well illustrated by the increasing levels of fragmentation and volatility of the electoral contests. The exponential growth of the number of political parties in Colombian elections and its consequences for democracy has been extensively discussed (Hoskin and Garcia 2006; Gutiérrez-Sanín 2007; Botero and Rodríguez-Raga 2009; Pachón and Shugart 2010; Dargent and Muñoz 2011; Albarracín and Milanese 2012; Pachón and Johnson 2016; Albarracín et al. 2018). Between the late 1950s and the mid-1990s, the party system was basically composed by two historical parties (Liberal and Conservative parties). After profound economic and institutional reforms in the early 1990s, the effective number of electoral parties increased by four between 1991 and 2002. The 2003 electoral reform slowed the process of fragmentation down, but it failed in reducing the effective number of parties or providing renewed incentives for party institutionalization.

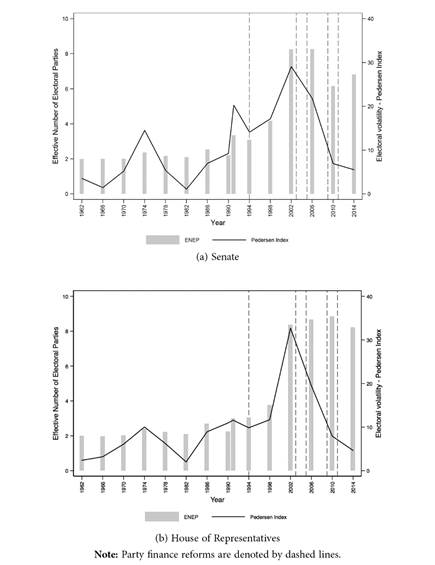

Using electoral data provided by CEDE-Uniandes (CEDE 2017), I calculate the effective number of electoral parties -Laakso-Taagepera index of the effective number of parties (Laakso and Taagepera, 1979)- for legislative elections in Colombia between 1962 and 2014. The results are clear: between 1962 and 1994 the average ENEP is two; it increases to 8 between 1994 and 2002; then after the 2003 electoral reform, the ENEP only decreased from 8 to 7 in Senate elections and remain the same (about 8) in House elections. According to some scholars, the ENEP actually rose to a certain extent in state-level (departamentos) elections after 2003 (Milanese et al. 2016).

Our knowledge about electoral volatility in Colombia is more limited. We know that electoral volatility increased exponentially in the 1990s and the early 2000s. New contenders emerged and captured substantial vote shares, and voters moved from traditional parties to newer movements (Albarracín et al. 2018, 232-234). However, electoral volatility has apparently decreased after the 2006 legislative elections (Albarracín et al. 2018).

Using data provided by CEDE-Uninades (CEDE 2017), I calculated the Pedersen Index of Electoral Volatility (Pedersen 1983; Powell and Tucker 2014) for Colombian legislative elections between 1962 and 2014. In both Senate and House elections, electoral volatility was very low between 1962 and the early 1990s. After 1991, electoral volatility was at least three times higher and reached peak values in the 2002 and 2006 legislative elections -Mainwaring (2018) estimates that the cumulative electoral volatility in Colombia between 1990 and 2014 was 64% . However, preliminary estimations suggest that the Pedersen Index has substantially decreased after the 2006 legislative elections.

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the ENEP and the Pedersen Index of Electoral Volatility for Colombian legislative elections between 1962 and 2014. Both panels (a) and (b) show that: i) the level of electoral fragmentation increases substantially between 1982 and 2002, and then it is relative steady between 2002 and 2014 (around ENEP = 8); and ii) the level of electoral volatility increases substantially between 1982 and 2002, and then it goes down drastically between 2006 and 2014.

Figure 1 also marks (in dashed red lines) the years in which electoral and political finance reforms were implemented. Figure 1 shows us two clear trends. First, electoral fragmentation and volatility were increasing since the mid-1980s (probably as a result of political decentralization and the implementation of local and state elections). And second, while electoral fragmentation remained stable, electoral volatility substantially decreased after 2006.

Source: Author’s calculations based on CEDE (2017).

Figure 1 Electoral volatility, effective number of parties, and political finance reforms, Colombia, Legislative Elections, 1962-2014

The 1991 Constitution and the 1994 Electoral Reform established more flexible rules for private donations, expanded the public funding scheme (using reimbursements), and facilitated parties’ access to low-cost loans. The aim was to lower entry barriers for small and new parties and remove disparities between dominant and minor parties. This new regulatory framework clearly favored newcomers and short-term electoral economies.

As a consequence of these more flexible rules, small and new parties flourished and private donations flowed effortlessly to electoral campaigns -including illegal donations from drug-traffickers to presidential campaigns (Rettberg 2011). The ENEP increased substantially because more political parties were able to participate in electoral contests. As more players entered electoral competition, electoral volatility also increased. Figure 1 shows that electoral volatility rose almost threefold between 1990 and 2002 and was particularly pronounced in House elections.

As discussed in section 2, electoral and political finance reforms were more frequent after the 2002 elections. As described in Table 1, the electoral laws approved after the 2002 elections were aimed to reduce electoral fragmentation, consolidate political parties or new electoral coalitions, and reduce the influence of private donors (specially drug-traffickers and illegal armed actors). However, the expansion of direct and indirect public funding schemes is perhaps one of the most important aspects of these reforms. The role of the state in funding electoral campaigns through the provision of ex-ante public subsidies and ex-post reimbursements was substantially expanded (Londoño 2018).

It seems reasonable to argue that every new restriction imposed on private donations or campaign spending was reciprocated by an increase in public funding provisions. For example, the adoption of ex-ante subsidies (the so-called anticipos) in 2005 seems to have been a response to new limits on corporate donations. The same electoral reform also reduced minimum vote thresholds for parties to receive public subsidies (from 5% to 4%). Similarly, the 2011 party finance reform established new limits on private donations and banned anonymous and foreign donations, but it simultaneously increased the ex-ante public subsidies (Londoño 2018, 44).

Since 2003, the intention of every electoral reform has been to replace private donations with public funding. However, this is an unfulfilled ambition. First, the influence of (legal and illegal) private donors cannot be effectively measured. Some sources suggest that private donations have remained the same or even increased in the most recent electoral contests (Londoño 2018, 105-110). And second, the EMB has no real capacity to monitor and enforce new limits and bans on (corporate, anonymous, and foreign) donations. The EMB regularly sets limits on campaign spending, but once again, it does not have institutional capacity to enforce them or efficiently punish lawbreakers. The EMB is not even able to enforce reliable reporting among recipients of public subsidies.

Therefore, new public subsidies increasingly supplement rather than replace private donations. In the past 15 years, Colombian political parties have successfully managed to boost their revenues by systematically approving electoral and party finance reforms that expand direct and indirect public subsidies without effectively reducing private donations or improving oversight mechanisms. This strategy has allowed some of them to stabilize their electoral performance, despite persistently high levels of fragmentation. In fact, Figure 1 shows that electoral fragmentation is still a persistent feature of the Colombian party system, but electoral volatility has decreased substantially after 2006.

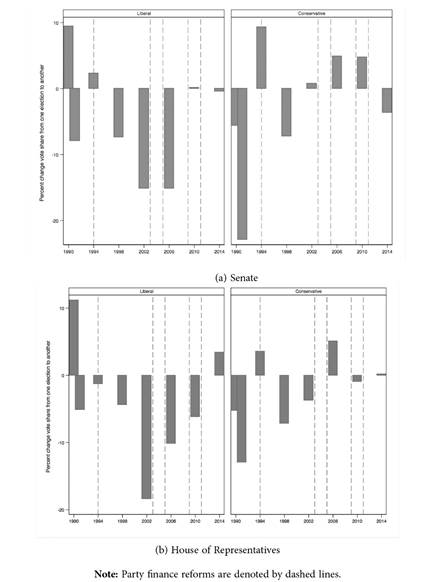

In other words, the most recent electoral reforms have effectively reduced the level of electoral uncertainty for roughly the same number of political parties. Figure 2 illustrates this “stabilization” effect for the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party. The percent change of their vote shares from one election to another was quite volatile before 2003. But the changes are much lower after the successive electoral reforms in the 2000s. Figure 2 indicates that both parties have received relatively stable electoral support after the 2006 legislative elections.

Source: Author’s calculations based on CEDE (2017).

Figure 2 Change electoral support traditional parties, Colombia, Legislative Elections, 1990-2014.

Figures 1 and 2 show that the most recent party finance reforms have reduced electoral volatility for dominant parties instead of reducing the overall number of parties in the elections. Consequently, there was no trade-off between private donations and public subsidies. On the contrary, candidates and political parties saw their revenues boosted as a result of the substantial expansion of direct and indirect public subsidies. And given the lack of effective monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms, parties kept receiving (legal and illegal) donations from individuals and organizations.

Since 2003, a relatively constant number of legislative parties (mainly Partido Liberal, Partido Conservador, Partido de la U/Centro Democrático, Cambio Radical, Alianza/Partido Verde, and Polo Democrático, with all their regional and local franchises) promoted several party finance reforms that boosted their revenues. These additional revenues helped them to consolidate their electoral advantages over newcomers and reduce the level of uncertainty caused by the proportional voting. Consequently, in the past four legislative elections (2006-2018), the electoral support for the political parties mentioned above has remained relatively stable.

The relative predominance of these political parties was also strengthened by the introduction of tougher requirements for the granting of public subsidies to newer parties. For example, new political parties are required to reach higher vote thresholds in order to get ex-ante subsidies. In addition, indirect subsidies like free media time are also allocated in accordance to the number of congressional seats the parties won in previous elections. Similarly, the distribution of on-going funding to improve internal mechanisms of candidate selection or training schemes for minority candidates are also allocated in accordance to the number of congressional seats or votes that the parties received in previous elections.

Concluding remarks

In sum, this paper shows that electorally-dominant political parties in Colombia have successfully created a regulatory framework to boost their revenues and constrain the growth of minor parties. Dominant parties have privileged access to public funds. This is not only a key factor behind their electoral success, but it also shapes their relationship with the state at different levels of the policy-making process. In line with the cartel party argument (Katz and Mair 2009; Biezen and Kopeckỳ 2014), this paper provides some empirical evidence that existing legislative parties (despite their programmatic differences) have reformed the political finance rules to reduce the level of electoral volatility and prevent new parties from entering the electoral arena. In some way, the growing “intensity” of Colombian party finance regulation works as an insurance mechanism for existing parties to boost their revenues and guarantee their success in a highly volatile electoral environment.

The emergence of cartel parties in Colombia follows some patterns clearly identified by cartel party scholars: i) political parties are now more financially dependent on state subventions to fund their activities (and consequently, less dependent on membership contributions or grassroots funding); ii) the party finance system privileges dominant rather than minor parties; and iii) political parties are becoming increasingly regulated or shaped by the state. However, unlike other cartel party systems, electoral fragmentation is persistent in Colombia and private donations have not been effectively replaced. Therefore, party finance rules in Colombia operate as a dual system in which minor parties rely on small or illegal donors, while cartel parties mainly rely on state funding. In this realm of duality, political parties behave like rent-seekers, and private interests groups are still better represented in the policymaking process than less organized citizens.