Introduction

Partisan independence is a concept that, until recently, has seldom been the focus of attention in the literature on political behavior. Instead, it has generally been viewed as the simple absence of partisan identification. However, the continuing electoral demise of “historical” parties in Europe and other regions, from France and Italy to Costa Rica and Honduras; the volatility of electoral choices; the growth of abstentionism; blank ballots and a divided vote in concurring elections have all underscored the importance of understanding the causes and consequences of partisan independence.

Many countries have experienced a significant growth in the number of electors who describe themselves as independents. In Latin America in particular, partisan independence has become an important subject of research. Studies on the issue have focused on Costa Rica (Sánchez 2002); Mexico (Estrada 2006; Temkin et. al. 2008; Temkin and Cisneros 2015); Argentina (Brussino and Vaggione 1995); Colombia (Sarthou 2006); Nicaragua (Saldomando et al. 2011) and Chile, Uruguay and Brazil (Hagopian 1998). Electoral and partisan dealignment in Latin America has been diagnosed and measured using the following indicators: 1) heightened electoral volatility; 2) increasing abstentionism; 3) decreasing trust in electoral institutions; 4) growth of divided and null votes; 5) negative appraisal of political institutions, particularly political parties. These five factors are strongly linked to a general process of political dealignment and growing partisan independence (Alcántara 2004; Alcántara and Freidenberg 2001; Hagopian 1998; Lupu 2016; Sánchez 2002; Sarthou 2006).

Within this line of research, the specific objective of this article is to present an analytical extension to Fiorina’s “running tally” approach to party identification through empirical testing using data from Latin America in order to include partisan independence as a possible outcome of negative retrospective evaluations of governmental performance. The results obtained in this study show that this modification to Fiorina’s approach provides the strongest prediction of partisan independence in comparison with sociological, cultural, modernization and political-institutional approaches. This finding constitutes an original contribution both to the literature on partisan independence and to the particular case of electoral dealignment in Latin America.

The article is organized as follows: First, the classical concept of partisan identification as well as Fiorina’s crucial contribution to the subject are discussed. Particular attention is paid to Fiorina’s virtual exclusion of partisan independence in his “running tally” model. Second, a number of alternative approaches to the understanding of the factors impacting partisan identification (permanence or change) are identified and analyzed. Third, the different factors that the competing approaches consider relevant are operationalized and included as variables in a probit model. This is followed by an instrumental model to account for the possibility of inverse causality between partisan independence and the retrospective evaluation of governmental performance. Finally, the findings and implications of the empirical analysis are discussed in terms of the principal-agent model.

1. Partisan Identification and Partisan Independence: Fiorina’s contribution

In 1960, a major step was taken in the field of electoral studies at the University of Michigan with the emergence of the concept of partisan identification. In the book The American Voter, partisan identification was conceived as the “individual’s affective orientation to an important group-object in his environment” (Campbell et al. 1960, 121). It was argued that this orientation was persistent over time and helped to explain the political behavior of a person, shaped by identification with a political party and a product of socialization during childhood and adolescence. This notion was originally conceptualized as basically unchanging, or at least, very stable, assuming its virtual immunity to political and economic changes except under truly extraordinary circumstances (Campbell et al. 1960). Thus, from its origin, partisan identification was conceived as an exogenous variable that affects politics but that is little affected by politics itself (Holmberg 2007). Because of this, partisan identification was not considered merely an opinion, but rather an identity (Green, Palmquist and Schinckler 2002). Generally speaking, the Michigan school proposal argued that partisan identification is the most important factor for explaining electoral decisions. Its usefulness, according to Arzheimer and Evans (2008), lies in that it is different from the mere intent to vote, as it has a substantial impact on voters and is sufficiently stable at both the individual and aggregate levels. Also, it was conceptualized as an efficient shortcut for interpreting information that allowed citizens to use their partisan sympathies to decide which policies or candidates to support -this being an important source of the mobilizing capacity of political parties.2

However, various criticisms emerged in relation to the original approach of partisan identification. Questions were raised about whether partisan identification had an affective grounding, or if it was a more cognitive phenomenon. In fact, over time, partisan identity was increasingly considered as an “affinity”, “preference”, or “belonging to”, all three associated more with the rationality of the voter than with his or her emotions (Burden and Klofstand 2005).

A particularly powerful objection stressed the importance of retrospective evaluations as determinant elements behind partisan identification. For Fiorina (1981), partisan identification did not refer to an identity or an exogenous variable separate from political events; instead, it was the result of a “running tally” of retrospective evaluations of governments and parties -a “record” of the voter’s reaction to political and economic events of the past.

Fiorina’s contribution helped transform the understanding of partisan identification and was followed by more criticisms of the original conceptualization, which will be described and analyzed below. However, since the focus of debate was centered on the character of partisan identity very little was said about party independence itself. Clearly, research focused specifically on the causes of partisan independence has not been as systematic or as common as the investigations that address those members of the electorate who do identify with a political party. Fiorina himself described and analyzed the mechanisms of change in party identification without paying much attention to partisan independence. In his classical study, he argued that “when a citizen first attains political awareness, socialization influences … may dominate party identification … But as time passes, as the citizen experiences politics, party identification comes more and more to reflect the events that transpire in the world.” Thus, for him, “change in party ID is predictable from knowledge of an individual’s perceptions of recent events and conditions” (1981, 97). His analysis focused on the changes in identification from one party to another and did not relate to party independence as a possible consequence of changes in retrospective evaluations by voters. In fact, he claimed that the concept of party identification does not include independence as a distinct option, since partisan identification “is one-dimensional [and] independents are just people who have no particular identification with either party, not those who positively identify with ‘independence’” (Fiorina 1981, 105).

Fiorina’s model operates as follows: when a person begins to develop political awareness, the influence of early socialization experiences may determine their partisan identification, but with the passage of time they acquire more knowledge about politics, and as a result, their partisan preferences and loyalties become the reflection of past political events as they evaluate them. Thus, party identification is the result of retrospective evaluations by voters of the performance of party agents in government. Fiorina examined changes in party identification “from strong Democrat to strong Republican or from Democrat to Republican,” emphasizing the governing party in particular, pointing out, for example, that “…satisfaction with the incumbent republican administration should result in movement toward the Republican end of the scale” (Fiorina 1981, 94). Thus, in the analysis, prominence is given to the voter modifying their party identification in the direction of a different party, while the possibility that instead of a change in loyalty from one party to another, a negative evaluation of governmental performance could result in a change to partisan independence is not contemplated.

In spite of Fiorina’s virtual exclusion of the party independence option, this article will show that his “running tally” model contributes not only to the understanding of changes in the partisan identification of individuals from one party to another -particularly from a party of negatively evaluated incumbents to a party in opposition- but also to the comprehension of the impact of negative retroactive evaluations of governmental performance on voters who identified with a political party becoming independent.

This article examines the expectation that the more negatively voters evaluate government performance, the greater their propensity will be to not identify with any political party.

The model of principal-agent (Fearon 2002; Ferejohn 1986; Miller 2005) serves to explain this relationship because it assumes that the relationship between individuals and politicians is such that the welfare of the principal (the voter) is affected by the actions of the agent (the politician) and by the environment in which actions are performed. Given that the principal is not able to observe the conditions in which decisions are made or the personal characteristics of the agent, the principal will evaluate the results limited by the observation of the outcomes of the actions taken by the agent. Given these circumstances, the individual will assess government performance on the basis of the observed results of the decisions made by the agent, which will affect the proximity and support of the principal not just to a specific political party, but in many occasions to political institutions in general, including the rest of the political parties in contention. In other words, it will affect their partisan identification or independence, so that the more negative the assessment of government performance is, the greater the tendency to not identify with a political party.

In order to gauge the specific effect of retrospective evaluations on partisan independence it is necessary to control for the impact of other potential determinant variables. A fruitful way to identify those variables is to review the extensive literature that has attempted to unveil factors that cause party identification, and infer from these the factors that determine its counterpart, that is, party independence. In the following sections, the main approaches to the study of identification will be briefly summarized in order to identify the variables that each sees as causally related to party identification or independence.

2. Alternative Approaches to Party dentification

Aside from the “running tally” approach advanced by Fiorina, the main approaches in the study of partisanship are: socialization (Campbell et al. 1960), social modernization (Dalton, 2013), transformation of socio-cultural values (Diez 2007; Inglehart 1970; Inglehart and Carballo 2008), and political institutional structure (Batista 2012; Blais and Dobrzynska 1998; Curini and Hino 2012; Norrander 1989; Norris 1999).

The socialization approach considers that the individual’s process of identification with a political party begins to develop within the family (and the influence of other socialization agents) during childhood and adolescence. Those early influences generate loyalty and support for a specific political party and these affective and cognitive ties persist and are maintained through time. As pointed out by Converse and Pierce (1992) and Berglund et al. (2005), as the individual gets older, party identification becomes stronger and their continued electoral support for a political party solidifies. Thus, older people can be expected to have higher levels of partisanship than their younger counterparts, given the length of time they have maintained their support for the same party.

Even though the original socialization approach attributed a decisive weight to the impact of early socialization experiences on the development of strong ties with a specific political party and to the persistent influence of those bonds throughout the life of individuals, recent studies using the same approach have acknowledged the increased importance of later-life socialization agents and experiences (Anduiza, Cantijoch, and Gallego 2009; Buckingham 1997; Norris 2001). For example, the rapid and extensive development of internet associated technologies has allowed for the easier acquisition of political and other relevant information and this may have an impact on the political identity of individuals who are frequent users of those technologies (Buckingham 1997; Anduiza, Cantijoch, and Gallego 2009). Since the most assiduous consumers of the new sources of information are adolescents and young people, they may be subject to a “late socialization process” which has an impact on their partisan loyalties. This is an additional reason that supports the socialization approach’s expectation that more young people are independents compared to their older counterparts (Berglund et al. 2005; Converse and Pierce 1992).

An additional approach to partisan identification claims that some of the attitudes and values that explain the incidence of partisan independence are associated with generational change and concomitant transformations in the mindset of individuals. This approach is based on the premises of modernization theory and emphasizes the distinction between materialist and post-materialist individuals (Inglehart 1977) claiming that “economic development is associated with increasingly rational, tolerant and secular values” (Inglehart and Carballo 2008, 18). This cultural process also leads to the weakening of support for political parties because voters have more sources of information which allow them to exercise their decisions independently of partisan links (Dalton 1984), making them more aware of their individual condition and their views less traditional (Inglehart 1977). For these reasons, it is expected that individuals with post-materialistic values will more likely be independent whereas the materialists will probably continue to identify with a political party.

In the same sense, but from a sociological viewpoint, a number of researchers have argued that economic, social and cultural modernization and a parallel increase in the educational level of the electorate make partisan identification less functional for voters, producing a decline in partisanship in western democracies (Dalton 1984; Dalton and Wattenberg 2000; Shively 1979). This perspective suggests that the growth in the number of voters without a partisan identity is due to the ongoing process of modernization in advanced democracies and even though many voters still base their decisions on key messages emanating from parties, this situation has been declining as the political skills of voters have increased and the costs of acquiring information have diminished (Dalton 1984).

Since the modernization process has a direct positive impact on the educational level of the electorate, more voters are deemed capable of confronting political issues cognitively, thus diminishing their need to rely on partisan ties and therefore increasing the number of independents in developed democracies (Dalton 1984, 2012)3. Also, given that modernization theory maintains that the changes in partisan independence are caused by structural factors (economic development) and individual factors (level of education), it should be expected that at an aggregate level, the higher a society’s development, the higher the percentage of independent voters will be, while at an individual level, as voters become more educated, a greater propensity to partisan independence should be observed among them.

The three approaches presented above suggest that partisan identification and, of course, partisan independence are influenced by cultural and sociological factors. However, politics and institutions also play an important role in shaping them. This constitutes the main claim of the “political-institutional” approach. Norris (2003) suggests that the Michigan school focused its attention on voting preferences at an individual level, failing to recognize that there are different levels of partisan identification according to the type of electoral system and parties and points out that “substantial literature has sought to analyze how voters respond to the electoral choices before them, based on the evidence from individual-level national surveys of the electorate, and more occasionally experiments or focus groups, often studied within each country or region in isolation from their broader institutional context” (Norris 2003, 3). One important strand within this approach has suggested that the Effective Number of Parties (ENP) has a positive relationship with partisan independence (Blais and Dobrzynska 1998; Curino and Hino 2012). As the number of parties increases, voters have more options to identify with, and they become less loyal to one party in particular. Individuals can transfer their preference from one party to another with greater ease given the large number of partisan options available.4 This increases electoral volatility and therefore strengthens the association between the percentage of independent partisans and the effective number of parties. Thus, the ENP operates as a proxy variable for party system institutionalization.

In Latin America in particular, political parties have been characterized as being weakly rooted in society, with increasingly fragile links between them and the voters (Mainwaring and Scully 1995; Mainwaring and Torcal 2005; Mainwaring and Zoco 2007; Lupu 2016).5

3. Operationalization of the Variables

The data used for the empirical analysis in this study comes from the 2010, 2012 and 2014 rounds of the Americas Barometer Survey of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) of fourteen Latin American democracies.6 The operationalization of the variables proposed by the approaches listed above is based on the information generated in those surveys.

The procedure by which Fiorina measures the impact of past events on partisan identification involves a group of variables that are instrumental to party identification itself. The author carries out a regression analysis where the dependent variable is the identification with a political party, and the independent variables are a group of socio-economic and demographic characteristics as well as general retrospective evaluations about different aspects of governmental performance.7 The fitted values of the regression are then used as an independent variable in a model that considers the voter’s party identification a year on, as a dependent variable. Even though this measurement refers to the change in identification from one year to the next, the instrumented variable is party identification itself, and therefore it does not solve the problem of potential inverse causality between retrospective evaluation and the identification with a political party. As Holmberg (2007, 562) points out, reciprocal causality is a potential problem in this regard, because “party identification is shaping behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions at the same time as it is shaped by attitudes and perceptions as well as by behaviors.” In fact, Fiorina (1981, 97-98) recognizes that “party identification… is both cause and consequence of some kinds of political behavior. To take it purely as the former may lead to statistical misspecification and substantive error.”8 Thus, it remains necessary to solve the issue of mutual causality between party identification (or party independence) and retrospective evaluation of performance. This can only be done through a procedure that can isolate the impact of the latter variable on the former.

To confront the problem of possible inverse causality, an instrumental variable is used in this study to isolate the effect of the evaluation of government performance. This operation is carried out by means of a variable that is only related to partisan independence through the assessment of governmental performance and not otherwise. The variable utilized in this study was the perception of insecurity in the voter’s neighborhood of residence across the Latin American countries (Table 1).9

Table 1 Perception of Insecurity

| Speaking of the neighborhood where you live and thinking of the possibility of being assaulted or robbed, do you feel very safe, somewhat safe, somewhat unsafe or very unsafe? | ||

| Perception of insecurity | Frequency | Percentage |

| Very safe | 14,218 | 21.94 |

| Somewhat safe | 26,338 | 40.65 |

| Somewhat unsafe | 17,143 | 26.46 |

| Very unsafe | 7,101 | 10.96 |

| Total | 64,800 | 100.00 |

Source: Compiled by authors with data from the America Barometer, LAPOP 2010-2014

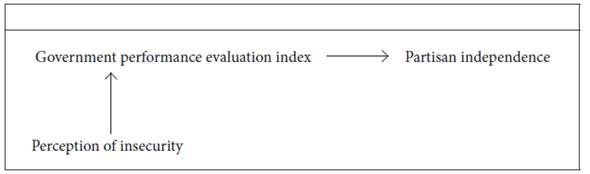

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the variables mentioned above. Clearly, the perception of insecurity has a direct impact on the evaluation of the government performance index, and only by bypassing the government performance index will it have an effect on partisan independence. There is evidence that shows how the perception of personal insecurity can shape governmental performance evaluation in Latin America (Pérez 2015). However, there is no logical theoretical argument that would pose a direct relationship between being independent or partisan and the individual’s perception of personal insecurity. In that sense, the only possible relationship between partisan independence and partisan identification with personal insecurity is through governmental performance evaluation. Although variations in the levels of personal insecurity might lead to a change in partisan identification from one political party to another, this consequence is explained by changes in governmental approval and not by personal insecurity itself. In addition, these variations might affect partisan identification among political parties but do not necessarily lead to partisan independence. Even if an empirical relationship was found between those two variables, that relationship would be spurious because it would be mediated by the evaluation of government performance.

Once the instrumental variable was selected, its impact on the perception of governmental performance index was calculated. Then, the fitted values of the relationship were associated with the dependent variable, thus isolating the correlation with the error in the dependent variable and eliminating inverse causality in the direction stipulated, that is, from party independence to the evaluation of government performance.10

With respect to the other approaches, the operational variable for the socialization perspective is simply the age of the voter. The older the individual, the stronger their partisan identification will be.

The variable used as the indicator of materialist or post-materialist values is belonging to a religion. Voters who manifest that they belong to a religion will tend to have stronger partisan identification than those who don’t.11

In relation to the modernization perspective, two measures at different levels of analysis were used. At the individual level the educational level is used, which is a numeric variable that counts the years of study of individuals; this variable registered values from 0 to 18 years. Meanwhile, at the aggregate level, development was measured through the GDP and the GDPpc by country (“GDP (current US$)” data from The World Bank).

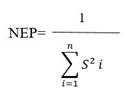

With respect to the institutional approach, all the variables included correspond to country level. The effective number of parties was calculated using the index of Laakso and Taagepera (1979) taking as reference the electoral results of the recent elections for each country of the region through the formula,12

The descriptive statistics for all the variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Dependent and Independent Variables

| Variable | Observations | Media | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

| Index of Government Performance Evaluation** | 61620 | 5.45e-11 | 1.518 | -3.119 | 2.611 |

| Secular values (Belonging to a Religion) | 63712 | 0.887 | 0.316 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Age | 64923 | 39.432 | 15.973 | 16 | 98 |

| Effective Number of Parties+ | 65143 | 4.948 | 2.444 | 2.58 | 10.95 |

| Log GDP+ | 60927 | 25.19 | 1.531 | 22.914 | 28.441 |

| Log GDPpc+ | 60927 | 8.638 | 0.691 | 7.336 | 9.632 |

| Years of education | 64824 | 8.931 | 4.509 | 0.0 | 18.0 |

| Gender | 65142 | 0.505 | 0.499 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Wealth*** | 64920 | -2.97e-09 | 1.886 | -4.619 | 2.883 |

| Year 2010/2012 | 65143 | 0.938 | 0.814 | 0 | 2 |

+ Variables at country level

** The index of Performance Evaluation is calculated on the basis of a principal components analysis, following the work of Corral (2008). The questions that make up the index are: 1) To what extent would you say the current administration combats government corruption? 2) To what extent would you say that the current administration is managing the economy well? 3) To what extent would you say the current administration improves citizen safety? Higher values of the performance variable mean a negative evaluation.

***Because the income variable generates much missing data, the Wealth index was built in accordance with the work of Cordova (2009) who used the principal components technique combining questions about ownership of home appliances and other goods. The questions used were: Could you tell me if in your house you have a television set? refrigerator? conventional telephone? cellular phone? car? washing machine? microwave oven? source of drinking water? toilet room? computer?

Source: Authors’ estimates, using data from America Barometer, LAPOP 2010-2014.

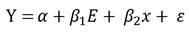

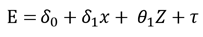

A statistical analysis was carried out with this data which consisted of two different probit models with instrumental variables to verify the robustness of the empirical findings. The formal specification of the model is the following.

The original model with the evaluation of government performance (E) endogenous was:

The first stage was to obtain the predicted values for E

Then, we include those predicted values (Ê) into the “second stage equation” with other control variables (x). In this case the dependent variable is partisan independence (Y).

The results of the model and their interpretation are presented in the next section.

4. Empirical test: Partisan Independence in Latin America

At the outset it is important to note the clear variability in the proportion of partisan independents in the different Latin American nations. A reasonably high percentage of individuals do not identify with a political party. In fact, more than two thirds of voters say they do not sympathize with any political party. Table 3 shows that from 2006 to 2014, 65 percent of individuals in the region did not identify with a political party.13 However, there are significant variations among the different countries.

Table 3 Independents in Latin America 2006-2014

| No. | Country | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | Mean (2006-2014) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guatemala | 85.28 | 84.14 | 81.69 | 87.07 | 88.58 | 85.35 |

| 2 | Chile | 74.40 | 78.58 | 88.94 | 85.66 | 86.91 | 82.90 |

| 3 | Peru | 70.15 | 80.83 | 78.76 | 83.65 | 80.77 | 78.83 |

| 4 | Argentina | -- | 75.25 | 80.55 | 73.10 | 74.33 | 75.81 |

| 5 | Bolivia | -- | 72.68 | 66.71 | 84.20 | 74.35 | 74.49 |

| 6 | Ecuador | -- | 81.06 | 84.31 | 77.52 | 54.82 | 74.43 |

| 7 | Brazil | 65.87 | 74.81 | 68.55 | 69.57 | 77.04 | 71.17 |

| 8 | Colombia | 71.41 | 70.83 | 62.77 | 74.47 | 71.79 | 70.25 |

| 9 | Panama | 79.24 | 67.94 | 69.69 | 73.99 | 54.37 | 69.05 |

| 10 | Mexico | 50.81 | 67.84 | 71.50 | 63.86 | 72.26 | 65.25 |

| 11 | El Salvador | 68.71 | 59.06 | 65.57 | 69.09 | 55.26 | 63.54 |

| 12 | Venezuela | 67.48 | 67.42 | 65.69 | 53.06 | 55.49 | 61.83 |

| 13 | Costa Rica | 63.84 | 69.73 | 47.70 | 73.80 | 32.64 | 57.54 |

| 14 | Honduras | 55.78 | 51.26 | 56.27 | 60.28 | 59.96 | 56.71 |

| 15 | Paraguay | -- | 41.00 | 60.83 | 54.28 | 59.70 | 53.95 |

| 16 | Nicaragua | 50.17 | 59.70 | 56.98 | 45.55 | 53.06 | 53.09 |

| 17 | Uruguay | 46.67 | 49.56 | 33.80 | 46.56 | 40.00 | 43.32 |

| 18 | Dominican Republic | 39.61 | 29.74 | 45.53 | 36.55 | 45.71 | 39.43 |

| Total | 63.82 | 66.33 | 65.21 | 66.47 | 63.17 | 65.00 | |

Source: Compiled by the authors using data from America Barometer, LAPOP 2006-2014.

In Guatemala and Chile the percentage of independent voters is greater than 80 percent. In Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil and Colombia the percentage is more than 70 percent. In Panama, Mexico, El Salvador and Venezuela it exceeds 60 percent, while in Nicaragua, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic the lowest percentages of partisan independence are found, because in the latter two countries 43.32 and 39.43 percent of citizens, respectively, do not identify with any political party.

Thus, it appears that the range of variation in the region is nearly 50 percentage points, with Guatemala being the country with the largest number of independents and the Dominican Republic with the least. It also transpires that there is stability over time in relation to this type of voters in each of the countries -except Costa Rica, Ecuador and Panama, where changes between one measurement and another of 20 percent are observed- in general the data does not change drastically from year to year, remaining basically constant from 2006 to 2012. For example, in Guatemala the percentage of non-identified voters does not fall below 80 percent, while in Uruguay the percentage of voters without partisan identification maintains between 35 and 45 percent. The same can be said about Mexico, where it remains above 60 percent.

What factors explain these differentials in partisan independence among Latin American countries? Most of the studies regarding the issue of partisan independence in Latin America have been casuistic and focused mainly on the process of dealignment that exists in the region, without examining the factors that may explain the differential levels of partisan independence. The evidence presented below constitutes a first bid to fill this gap in the literature and hopefully contributes to a better understanding of partisan independence in Latin America.

Table 4 presents the results of the analysis.14 As shown here, the associations between the independent variables and the dependent variable (partisan independence) in the three models generally occur in the same direction. Also, the statistical significance of the variables remains constant (except for the variable years of schooling), validating the strength of the findings.15

Table 4 Determinant Factors of Partisan Independence in Latin America 2010-2014

| Partisan Independence | PROBIT Model (Robust Standard Error) | Two Stage PROBIT Model (Robust Standard Error) | Instrumental PROBIT Model (Robust Standard Error) |

| Performance and Attitudinal Variables | |||

| Performance Evaluation (worsens) Predicted probabilities for Performance Evaluation after First Stage Model Performance Evaluation (worsens) = Perception of insecurity | 0.106*** [0.016] | 0.264*** [0.059] | 0.283*** [0.062] |

| Postmaterialist Variables | |||

| Secular Values | 0.011 [0.048] | 0.011 [0.048] | 0.014 [0.045] |

| Socialization Variables | |||

| Age | -0.010*** [0.001] | -0.009*** [0.001] | -0.009*** [0.001] |

| Institutional and Political Variables | |||

| Effective Number of Parties | 0.080** [0.029] | 0.086** [0.030] | 0.067** [0.026] |

| Modernization Variables | |||

| Years of Education | -0.006 [0.005] | -0.006 [0.004] | -0.009* [0.005] |

| Log GDP | 0.057 [0.050] | 0.057 [0.052] | 0.049 [0.045] |

| Log GDP pc | -0.157 [0.096] | -0.170* [0.096] | -0.113 [0.091] |

| Control Variables | |||

| Gender (Feminine=1) | 0.091*** [0.016] | 0.096*** [0.016] | 0.080*** [0.016] |

| Wealth | -0.028** [0.011] | -0.023** [0.011] | -0.038*** [0.011] |

| Year 2012 2014 | 0.041 [0.141] -0.079 [0.123] | 0.064 [0.136] -0.061 [0.122] | 0.007 [0.144] -0.121 [0.121] |

| Constant | 0.270 [0.869] | 0.344 [0.908] | 0.199 [0.773] |

| Observations | 58873 | 61840 | 58634 |

| Number of Countries-Year | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Wald chi2 | (11) = 659.04*** | (11) = 481.76*** | (11) = 688.49*** |

| Log pseudolikelihood | -36627.99 | -38805.99 | -142978.94 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.054 | 0.043 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Percentage of Correction Classification | 66.58% | 65.66% | 64.84% |

| Wald test of endogeneity | Chi2 (1)=7.14 Prob > chi2= 0.008* | ||

| Area under ROC curve | 0.634 | ||

Standard error between brackets ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1

Source: Calculated from the database of LAPOP 2010-2014.

The main difference that presents itself in the regression models occurs when the instrumental variable that controls for the potential effect of inverse causality is introduced (Two Stage PROBIT Model and Instrumental PROBIT Model). When that introduction is carried out, the coefficient of association between the evaluation of government performance and partisan independence gains a stronger explicative power.16

Thus, in comparison with the PROBIT model, in the Instrumental PROBIT (IPROBIT), the index of evaluation of government performance increases its impact on the dependent variable, demonstrating the importance of the utilization of the instrumental variable.

To summarize, when discarding the effect of reciprocal or inverse causality, the index of evaluation of government performance displays a positive association with the dependent variable, so that when that assessment worsens, a stronger individual propensity to partisan independence exists. This confirms that the evaluation of governmental performance does not only have an impact on the change in support from one party (the incumbent) to another (in opposition) as proved by Fiorina (1981), but also in the distancing of voters from all political parties. This result is very important because it allows the “running tally” approach to be extended to include voters that become independents, showing that negative assessments of governmental performance do not just affect voters’ identification with the ruling party, but also negatively impact partisan identification in general, causing a significant growth in the level of de-alignment with all political parties.17

The findings in the IPROBIT model regarding the rest of the independent variables considered were:

1) The prevalence of secular individual values does not significantly affect the weight of independent voters in the electorate. Contrary to the expectations derived from the generational value change approach, when controlling for inverse causality, a positive but not significant relationship was found between secular values held by individuals and partisan independence.

2) As expected by the socialization approach, age has a negative and significant association with the dependent variable. The older the individual, the lower their probability of being independent. The longer an individual stays loyal to a specific political party, the less probable it is that he/she will become independent (Berglund et al. 2005, 112; Converse and Pierce 1992).

3) Concerning institutional variables, the effective number of parties (ENP) shows a statistically significant positive relation with partisan independence. This result confirms the position of Blais and Dobrzynska (1998) and Curino and Hino (2012), who have argued that when the number of parties is larger voters have more options for identification and they become less loyal to a specific political party.

4) Among the variables related to modernization in the IPROBIT model, only years of schooling is statistically significant which means that when the individual is more educated they are likely to identify with a party. Contrary to Dalton’s perspective (1984), in Latin America, years of schooling are positively associated with higher partisan identification. However, at the aggregate level the development measures show that neither GDP nor GDP per-capita have an impact on partisan independence.

5) Regarding the control variables, the results showed a positive and significant association between gender and partisan independence, women being more prone to be independents. As for wealth, it is related negatively with the dependent variable, since higher levels reduce the individual’s propensity to partisan independence.

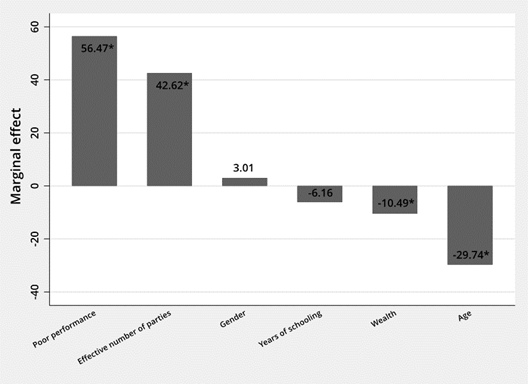

A more substantial interpretation of the results reveals the impact of each one of the statistically significant variables in the IPROBIT model, through the estimation of their marginal effect on the dependent variable (partisan independence), leaving the rest of the variables constant in their observed mean value. As can be seen in Figure 2, the negative evaluation of government performance is the variable with the greatest marginal effect on the dependent variable of interest. When that evaluation passes from its minimum to maximum value, partisan independence increases by more than 55 percent. This result proves that the assessments voters make of the performance of the incumbent government may lead not only to a change in identification from one party to another as claimed by Fiorina (1981) in his classical study, but also to a distancing of voters from all existing parties, at least in Latin America.

Source: Original Calculations based on I-PROBIT model p<0.05

Figure 2 Marginal Effect on Partisan Independence Minimum-Maximum

As for the rest of the statistically significant variables, a) the effective number of parties has an effect on the dependent variable of about 43 percent when passing from its minimum to its maximum level. Clearly, this variable increases the probability of being independent, but to a lesser degree than the assessment of governmental performance; b) the age variable has a negative impact of approximately 30 percent on the probability of being independent when passing from the youngest to the oldest individuals; c) wealth diminishes the probability of being independent by 10 percent points; d) as do years of schooling and gender, even though significant in the model, their marginal effects on partisan independence do not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

The results of the statistical analysis presented above indicate that the variables derived from the socialization and institutional approaches and particularly from the rational-evaluative (or “running tally”) perspective, have an important effect on the tendency of individuals to be or become independents in Latin America. Nevertheless, it is clear that the effect of the assessment of government evaluation has the most powerful impact over the voter’s propensity to partisan independence in the region. Thus, it can be concluded that the evaluation of governmental performance is the variable that best predicts partisan independence in Latin America. Also, the evidence shows that the evaluative-rational assessment of government performance impacts not only the passage from identification with one party to the other as claimed by Fiorina, but also the distancing from all political parties by the voter. This specific phenomenon has not been dealt in the literature on partisan independence before.

Having shown the effect that the evaluation of government performance has on partisan independence, how can this impact be explained? In other words, what is the mechanism through which disappointment with the incumbents can lead to the distancing of individual voters from all partisan attachments?

As discussed above, the model of principal-agent (Fearon 2002; Ferejohn 1986; Miller 2005) explains this relationship. Given that the principal cannot appraise the conditions in which decisions are arrived at, they will assess the results limited by their perception of the actions taken by the agent. Under these circumstances, partisan identification or independence will be affected, so that more negative evaluations of government performance will increase the tendency to not identify with any political party.

Numerous studies have proved that in both advanced and transitional democracies, evaluation of government performance determines the degree of trust that their citizens have in political institutions (Cattenberg and Moreno 2005; Corral 2008; Dalton 2004; Del Tronco 2012; Hagopian 1998; Mishler and Rose 2001; Newton and Norris 1999; Norris 1999; Salazar and Temkin 2007).18 Trust has a direct impact on the level of participation of the voters. Lower institutional trust leads voters to abstain from participating in elections (Bélanger and Nadeau 2005; Salazar and Temkin 2007) and abstentionism is seen as a symptom of political alienation and declining support for political parties (Hagopian 1998; Sánchez 2002; Sarthou 2006), often leading to an increase in partisan independence.19 Voters who perceive that the government is performing badly will tend to experience lower institutional trust, and therefore will be less inclined to identify with another political party, thus increasing the number of independents in the electorate.