Introduction

The South American Defense Council of UNASUR (CDS by its Spanish and Portuguese acronym) emerged between 2008-09 as a coordination initiative on security and defense issues common to the 12 sovereign South American states. Its origin was as encouraging as it was striking, insofar as it included the participation of some rival states, as well as some others whose security and defense interests were distant from each other. Ten years later, with the fracture of UNASUR, it is evident that those conditions of origin contributed to its underperformance. This article presents a complementary structural explanation to the CDS, pointing out missing geopolitical links analyzing data and facts related to the concentration of economic and national capabilities in the international system, as well as evidence of the geostrategic orientation of the US, and recent developments in South American regionalism. The findings of the research are that the CDS’ emergence and performance, as well as its recent disintegration, have been responding structurally to regional and global geopolitical transformations.

This research followed a structural realist approach, especially concerning the dominant role of the distribution of capabilities in the international system, and their character as an independent variable to understand both the individual and collective foreign policies. It also considered criteria from subaltern realism, such as sovereignty issues related to security in underdeveloped states.

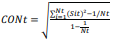

The realist approaches were linked global trends. Quantitative macro-data through Concentration of Capabilities (CON) formula (Mansfield 1993, 111)(1) capture global patterns. CON analysis brings depth to the debate on polarity, as it does not concentrate on the mere identification of poles of power, but rather it goes much further, indicating flows of capabilities throughout the international system. Accordingly, a system could be multipolar, with more than three poles or powers occupying dominant positions relating to their capabilities, but also be highly concentrated in this handful of powers. Alternatively, at the other extreme, the system could be unipolar, at least in the terms of William (Wohlforth 1999), but rest on a changing international structure, with dynamic flows of deconcentrating capabilities.

On the other hand, the analysis of US strategy lies on the National Security Strategy (NSS). The diachronic examination of these texts reveals an over-orientation of US geostrategy, following classical geopolitical priorities. The revision of the patterns of reorientation and emergence and relevance of US Geographic Combatant Commands (GCC) revealed that, in the midst of a process of high concentration of military might towards the US, the US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), with direct responsibility in Latin America, was losing relative importance to the emergence of a GCC for North America and another for Africa. All this while the US Central Command (CENTCOM) -for the Greater Middle East, and later the US Pacific Command (PACOM) taking paramount geostrategic importance.

The structure of this article is as follows. Firstly, a brief exposition of explanations on the CDS, starting from its initial objectives contrasting with regional security dynamics. The second and third parts present the geopolitical links in South American security regionalism explanation, highlighting the polarity and concentration of economic and military capabilities in the international system, the highly important geostrategic over-orientation of the US toward Eurasia and Asia-Pacific, and the divisive dynamics of South American regionalism. The conclusion points to the importance of including structural evidence and analysis to the study of security regionalism.

Explanations on South American Defense Council

Post-hegemonic regionalism is the dominant explanation for the rise of the most recent intergovernmental institutions in South America (Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012; Riggirozzi 2012; Briceño-Ruiz and Morales Moreno 2017). Its proponents affirm that Latin American regionalism, and especially South American regionalism, emerged at the start of the 21st century and responds to the latent collective interest of intraregional cooperation and interregional relations without the intermediation of the US and its liberal practices (Battaglino 2012a). It coincided with the rise of South American economies and the leaderships in the framework of the so-called “Pink Tide” (Panizza 2008). The redirection of national resources in terms of social welfare aimed at reducing social inequalities that can only been achieved by decoupling from the neoliberal model of the Washington Consensus. This combination of factors weakened US hegemony, offering an exceptional opportunity for South American countries to experiment with new forms of organization of their own, according to regional interests and aspirations.

One of the most important factors in this explanation refers to the almost simultaneous rise in South America of leaderships affiliated with the Sao Paulo Forum. This organization of leftist political parties and social movements emerged in 1990 as a response to the Soviet collapse and imminent Western hegemony under the US leadership. In this sense, the Sao Paulo Forum was the Latin American contestation to the Washington Consensus. The Pink Tide enforced new patterns of intraregional and extra-regional relationships, which altered the trends in South American regionalism. Until then, the principal regional blocs were commercial, as shown in the cases of the Andean Community and the MERCOSUR. These new leaderships began to include autonomy and international revisionism in regional integration agendas, motivating geopolitical ideas such as South American identity and multipolarity within post-hegemony.

It is important to consider that South American identity forms part of the Brazilian geopolitical project (Galvão 2009), which consists of giving symbolic and political importance to geographical facts. Near half of South American territory is occupied by Brazil, and moreover, it represents just less than half of the continent’s population and more than half of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). These structural attributes would give priority to Brazilian leadership, and make the region a unipolar system (Schenoni 2014). The aspirational role of Brazilian leadership was to Brasilia a potential platform for its reformist project of the UN Security Council, so that South American regionalism should not only extend to the whole region, but also abandon functionalist criteria and embrace a structural integration. Therefore, not only Brazilian objectives would be achieved, but it would also underpin South American autonomy and rebalance the international system in search of greater diversity in power poles (Vigevani and Cepaluni 2007). This scheme of the South American bloc, represented by the UNASUR project and led by the Brazilian Workers’ Party under the leadership of Luiz Inacio “Lula” Da Silva, was concordant with the autonomist, defensive and revisionist visions of the governments of secondary regional powers such as Argentina and Venezuela, or of lesser states such as Ecuador and Bolivia.

However, the post-hegemonic regionalism explanation presents flaws. Some have pointed out that this explanation does not take into account the domestic political agendas (Petersen and Schulz 2018), nor the changes in the balance of power in the region (Vaz et al. 2017). Explanations have also been developed that point out South American contradictions and competences due to national autonomy interests (Mijares 2018; Mijares and Nolte 2018; Mijares 2020), as well as presidential ideological volatility (Baracaldo Orjuela and Chenou 2018). These were theoretically predictable in the process of formation of the CDS, because of the nature of the issues assigned to the Council: coordination of security and defense policies in a region in which the importance of sovereignty and territorial integrity is a central aspect of national identity (Parodi 2002). This is insomuch as it warns of the South American zeal for sovereignty, as stated by the subaltern realism (Ayoob 1995).

Additionally, the performance of the security regional agreement has been a difficult test to overcome for post-hegemonic regionalism. According to its postulates, the advance of a multipolar international order and the decline of the US had to consolidate the regionalism processes started in early 21st century. On the contrary, the result has been that of a moment of post-hegemonic boom, followed by a period of languishing by the regional institutions emerged in the heat of the moment. In the case of the CDS, two trends, one maximalist and the other minimalist, which pulled in opposite directions, affected the institutional design. Chávez’s Venezuela aspired to the creation of a full military alliance -the “South Atlantic Treaty Organization” or “NATO of the South”- while the Uribe’s Colombia opposed to any initiative that put at risk its special relationship with the US (Tickner 2008; Gratius 2008; Mijares 2011; Comini 2015).

The result of these tensions was a compromise managed by the Chilean Foreign Ministry, with an institutional design that created a forum to coordinate policies which would serve to generate measures of mutual trust-as confirmed by the former Chilean Minister of Foreign Relations (March 13, 2009-March 11, 2010), Mariano (Fernández Amunátegui personal communication, January 15, 2015). In practice, post-hegemonic regionalism suffered from the South American geopolitical fault-line distinguished by the difference between the Atlantic states, MERCOSUR, and those of the Pacific, the Pacific Alliance (AP) (Nolte and Wehner 2015; Wehner and Nolte 2017; Briceño-Ruiz and Morales Moreno 2017). The objectives of the CDS were broken down in such a way that no signatory government would perceive a risk to its autonomy interests. These objectives are: 1) consolidate a zone of South American peace; 2) construct a common vision in defense matters; 3) articulate regional positions on defense in multilateral fora; 4) cooperate regionally in defense matters; 5) support actions of demining and the prevention, mitigation and assistance for victims of natural disasters (UNASUR 2009).

The first objective is difficult to evaluate, given that its operationalization is not trivial and there is no consensus on the so-called “zone of peace”. Jorge Battaglino convincingly argued that South American is a “hybrid peace” region. This “…characterized by the simultaneous presence of: 1) unresolved disputes that may become militarized, yet without escalating to an intermediate armed conflict or war; 2) democracies that maintain dense economic relations with their neighbor countries; and 3) regional norms and institutions (both old and new) that help to resolve disputes peacefully.”(Battaglino 2012b, 142). Under this type of peace, the use of force is probable and conflicts present themselves in the form of militarized crises (Battaglino 2012b, 134). In this sense, the region has a long history of militarized inter-state disputes (Mares 2001; Martín 2006), and there is insufficient evidence to indicate a change stemming from the CDS. South American hybrid peace continues to be a product of political dynamics and the limited military capabilities of member states (Jenne 2016), not of security regionalism.

The second and third objectives of the CDS, to build a common defensive vision, and to articulate regional positions on defense in multilateral fora, have been significantly lagging. Between 2011 and 2012, there was a period of rapid alternation of the Secretary General of UNASUR between Colombia and Venezuela. Colombia’s María Emma Mejía assumed the post from May 2011 to June 2012, then Venezuela’s Alí Rodríguez Araque, from June 2012 to July 2014. In this period, the idea dominant idea was harmonizing the defense doctrine of UNASUR through the CDS, centered on the defense of energy and natural resources. In June 2014, the conference “Defense and Natural Resources” took place in Buenos Aires (UNASUR 2014). These efforts, however, were in vain. According to the high-ranking military officials and diplomats of Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela who participated in the project of a South American doctrine (Argentine diplomat, personal communication, November 24, 2016; Colombian diplomat, personal communication, November 24, 2016; Venezuelan diplomat, personal communication, November 26, 2016), from the beginning of UNASUR and the CDS there had been a propensity to pompous declarations but mutual distrust or disinterest always prevailed (Venezuelan military officer, personal communication, November 26, 2016; Colombian military officer, personal communication, May 12, 2017). In terms of security, South American regionalism has also been declarative (Jenne et al. 2017).

Finally, neither the fourth and fifth objectives were achieved. Principles of sovereignty have prevailed and, facing the greatest natural disasters that South Americans have suffered in the last decade, no military force has crossed borders, nor been asked to do so. The classical concept of Westphalian sovereignty (Krasner 1999, 20-21) has prevailed. The explanation for this behavior lies on subaltern realism. According to this theory, to understand the importance of sovereignty in the Third World it is necessary to introduce elements of historical sovereignty in the formation of the state. Weak states tend to exalt elites who jealously guard national sovereignty, while representing their own power domain (Ayoob 1995; 1997; 2002).

On the other hand, there are the difficulties of multilateral cooperation in security and defense issues. Between 2009 and 2017, twelve executive-level meetings were held within the CDS. In parallel, at least twenty bilateral and sub-regional multilateral agreements have been signed on security and defense themes, especially related to borders issues.(2) Despite interest in the multilateralization of diplomacy in South American defense, the trend is of bi- or tri-lateralization, or limited multilateralization in the Southern Cone, the most stable security sub-complex in Latin America. In South American security and defense, multilateralism has given way to mini-lateralism in general issues, which do not affect the functioning of national agendas.

Missing Geopolitical Links

Complementing post-hegemonic regionalism, structural analysis could help to better understand the CDS. The main claim in this research points to include geopolitical factors in explaining the emergence and performance of the CDS. This explanation includes three factors: global geoeconomic patterns, global geostrategic patterns, and geopolitical dynamics of South American regionalism.

Global Geoeconomic Patterns ( 3 )

The shortcomings of post-hegemonic regionalism create a puzzle when applied to the most recent case of South American security regionalism. If we want to show with data that there has been a process of displacement of the relative power and influence of the US, as a causal condition of regionalism, it is necessary to use data such as that presented in Figures 1 and 2, in which the relative US (broad) national and economic capabilities facing South America. In this context, it is possible to see the stability of the gap in terms of composite material capabilities.

Evidence suggests stability in the distribution of power. The void remains exposed once an analysis of the evidence of the effective transformation, or not, of the inter-American system has been undertaken. As for the concentration of wealth capabilities, the pattern shows that international system experiences a sharp de-concentration during 2001-2008. Notwithstanding this change, an approximation to the concrete reality of the Western hemisphere demonstrates that the deconcentration could have had perceivable effects (Jervis 2015), but that regional patterns have barely changed. Even stronger is the result of the quantitative analysis of data related to national capabilities in general, in which there is evidence of a progressive re-concentration of capabilities in the hands of a few powers, to the detriment of the majority of states in the international system. This asymmetry is particularly marked in the Americas.

Application of CON formula demonstrates that during 1980-2013 trends in gross economic capabilities of the states of the world passed through two clearly definable stages. The first was high concentration, which is to say an increase in inequality, between 1980 and 2001, and the second of a rapid deconcentration, between 2002 and 2013 with a particularly high speed until 2008, in which the capability to attract wealth spread in the international system.

What explains the marked differences between one period and the other was the super-cycle of commodities. During 2000-2014, the general trend was an increase in the prices of raw materials stimulated by the demand from emerging markets (Radetzki et al. 2008; Erten and Ocampo 2013; Jacks 2013). From 2003, with the US intervention in and military occupation of Iraq, and the dramatic effect of the armed separatist revolts in the Niger Delta, together with the oil strike of the Venezuelan state-owned PDVSA, fossil fuels added strongly to the commodities push. This slowing the growth of highly industrialized economies, strengthening industrialization processes in the biggest emerging markets, and accelerating growth in the raw materials most dependent economies. Those events deconcentrated the global economy, favoring perceptions of parity, promoting the idea of multipolarity, and in some extreme cases, of non-polarity (Kupchan 1998; Haass 2008; Bremmer and Roubini 2011). In this context of catching-up and power parity towards power transition, the revision of the international system based on ever more autonomous foreign policy strategies appeared plausible.

However, the analysis of global economic concentration does not match that of military capabilities. Although subject to debate, it is difficult to counterargue that the pairing of economic and military capabilities continues to be a central piece in the definition of hierarchies of power in international politics. Even soft power theorists admit that hard power continues to be a fundamental instrument of global politics, as is shown by the development of the concept of smart power, based on the alternative and progressive use of instruments of soft and hard power (Nossel 2004; Nye 2009). Thus, economic and military capabilities still playing a leading role in analyses of international power relations.

Applying the same formula to variables of gross military power obtained from the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC)(4) (Singer et al. 1972), a distinct pattern becomes evident. Economic capabilities are only a part of the story in international politics, since power must consider military capabilities, then the results presented in Figure 2 represent a challenge to the definition of international polarity.

In late 20th century, Samuel Huntington affirmed that the world was experiencing a uni-multipolarity, or a game of multiple boards on which capabilities have different distribution and forms by sector (Huntington 1999). His analytical model, usually described with the metaphor of a three-dimensional chessboard, could be a solution to the apparent contradiction of economic deconcentration and the concentration of global military capabilities, at least as a global explanation but with potential deficiencies in regional analysis. However, uni-multipolarity is not a parsimonious explanation of world politics, due to its global perspective and its interest in explaining the system as a whole, as bipolarity did it during the Cold War. This is not feasible in a “world of regions” (Katzenstein 2015).

The differences between the patterns of concentration of economic and military capabilities are real, but the contradiction is apparent analyzing the global political reality from the angle of regions. To Katzenstein, global dynamics have been abandoning their dominant global character to adapt to a world of open and porous regions. Similarly, important IR scholars have been writing about these processes of regionalization in international security and international political economy (Buzan and Wæver 2003; Acharya 2013).

Privileging the regional perspective does not imply forgetting phenomena at the global level, but rather incorporating that in the context of the studied region. The contradiction presented in the types of capabilities, which cannot be fully resolved through the analytical model of uni-multipolarity is an apparent contradiction in the international system, but not necessary in regional systems. For a better understanding of regional dynamics, we should consider elements of the dominant political culture, patterns of cooperation and conflict, but principally the geopolitical criteria. Regional studies are mainly geopolitical analysis, since their spatial logic with respect to the incidence of global trends in spaces distinguishable as regions. This does not deny the ideational or behavioral dimensions of regions, but rather defends the relevance of the physical and structural condition for the definition. Seen in this way, we must reconsider the contradiction presented in Figure 2 and stop viewing it in the global context, to begin to see it from regional angles.

The geopolitical focus on regional realities brings us from a non-regionalized global perspective to a regional perspective, which considers the global. The pursuit of national objectives through the mobilization of ample resources in the form of a grand strategy (Liddell Hart 1967; Kennedy 1992; Christensen 1996; Gaddis 2002; Russell and Tokatlian 2013) or the management of geopolitical objectives through geostrategy (Brzezinski 1997; Walton 2007) across geopolitical realms. The form in which states of different capabilities react to others geostrategies, conditions the meaning given to them and, as a consequence, the courses of action they follow. The inclusion of this type of analytical approach adds the possibility of a dynamic interpretation, which would explain later processes, such as institutional performance.

Global Geostrategic Patterns

Drawing on the historical analysis applied to the study of international politics, an important missing link in the explanation of the new regionalism is the US geostrategic over-orientation toward Eurasia since 2001. This change is evident in 2002 NSS, and had an important impact on the international perception of South American governments. This was because, on one hand, the global conditions of hierarchy did not change; the system continued to be unipolar. On the other, the overstated geopolitical interest of the administration of George W. Bush in the Middle East and Central Asia opened an extraordinary window of opportunity for left-wing autonomist South American forces. Those demonstrated resistance to the globalization promoted during the Clinton era, and had growing financial resources derived from the super-cycle of raw materials.

It is impossible to separate the effect of South American autonomy from the geostrategy of the US. Prior to the most recent wave of South American regionalism, Zbigniew Brzezinski identified the strengthening of economic and military positions of occupation and influence in three key peninsulas of Eurasia, Europe, the Arabian Peninsula, and South-East Asia, as a great US geostrategic imperative (Brzezinski 1997). Meanwhile, Christopher (Layne 1997) cautioned against the convenience of offshore balancing in Eurasia as a replacement strategy for the primacy approach, which the US could not sustain in the face of slow but progressive decline. There has been continuity among US realist scholars in calling for offshore balancing, driven by an efficient use of power with the aim of avoiding a single or collective hegemony across Eurasia (Mearsheimer 2001; Innocent and Carpenter 2009; Pape 2010; Walt 2011; Mearsheimer and Walt 2016).

The geopolitical importance of Eurasia was reemphasized by Brzezinski in drawing on the work of Halford (Mackinder 2004) on the geographical pivot of history. Thus, Eurasia occupies a central position at the base of original geopolitical thought, implying the displacement of the importance of other regions, especially those without a great power. This explains the marginal position of South America in dominant geostrategic calculations, including those of a neighboring superpower such as the US.

For the geostrategy of the US, the most salient event after the geostrategic proposals of Brzezinski and Layne were the 9/11 attacks. These brought a reconsideration of US foreign policy priorities and national security, with the Western hemisphere virtually disappearing. The national security apparatus over-focused on Central Asia-Afghanistan since 2001-and the Middle East-Iraq since 2003-(Feffer 2003; Layne 2007). The accumulation of capabilities and the development of conventional combat skills from the time of the Cold War gave to the US its global military superiority. However, these capabilities and skills did not correspond to the multidimensional challenge of the War on Terror (Posen 2001), which consumed treasure and attention by the entire national security apparatus (Sloan 2008; Cohen 2004).

Beyond the actual event, September 11th occurred in the midst of a large-scale economic process with the potential to lead to a transition of power: the material rise of China. The possibility of this power transition has been widely debated, with no agreement on the real prospects of a peaceful or conflictive transition (Zhu 2006; Tammen and Kluger 2006; Lebow and Valentino 2009; Mearsheimer 2010; Allison 2017). What is certain is that China presented impressive numbers, which reinforced the hypothesis of US decline and forced Washington strategists to take more seriously the necessity of maintaining presence and influence in Eurasia. The development of this geostrategy did not stop with the end of the Bush administration, extending into the Obama administration and achieving its climax in 2011 with the “Pivot to Asia” doctrine (Campbell 2016).

Additionally, Russia experienced a resurgence driven by two factors: the oil boom, and the rise of the assertive leadership of Vladimir Putin (Stuermer 2008). The Russian awakening reactivated the dynamics of geopolitical competition with the US. The relationship of energy cooperation between China and Russia was only part of the joint strategy to displace the US in Central Asia (Klare 2002). The process of security cooperation, started in 1996 with the creation of the Shanghai Five forum, including China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, led to a bilateral border demilitarization measure between China and Russia in 1997 (Tsai 2003). The Shanghai Five evolved into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001, including Uzbekistan (Marketos 2008; Frost 2009). The strategy of regional access-deny was clear. Brzezinski’s warning points to the possibility of cooperation between three Eurasian powers. China and Russia were the most important because of their material capabilities and long history of rivalry with the US. The third power is Iran. Because of its dimensions and capabilities, Iran is not in the same league as China or Russia, but the oil boom, and the antagonistic leadership of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) compounded its central position in Eurasia. Encouraged by the advantages afforded by high oil prices, Ahmadinejad implemented a balancing strategy toward the West (Ansari 2007). This confrontation reached the point of sanctions against Iran for the secrecy in its nuclear program. While there is no evidence of an alliance between China and Russia with Iran, the first is the principal buyer of Iranian oil (British Petroleum 2017), while the latter is its principal supplier of arms, with China second (SIPRI 2017). These geopolitical links appeared to close the Brzezinski’s Eurasian triangle, threatening the interests and influence of the US in the super-continent.

That situation does not account for any serious US decline in terms of quantifiable capabilities. On the contrary, the geostrategic maneuvers of China, Russia and Iran, together with US military efforts in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, stimulated an increase in US military spending and thus the concentration of capabilities. What declined was US interest in hemispheric matters, whose importance paled in comparison to the hot spots of the national security agenda on the other side of the world. Even the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) initiative, indirectly associated with national security policy, suffered the disinterest of its main promoter, opening the doors for a greater demonstration of post-hegemony in South America. A successful parallel summit of resistance to the FTAA in the framework of the IV Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, on November 4-5, 2005, in which Néstor Kirchner and Hugo Chávez declared the agreement’s death.

The geostrategic over-orientation to Eurasia appears in the US NSS documents of the (Bush 2002; 2006) and (Obama 2010) administrations. The first abandoned any reference to the previously mentioned FTAA and drastically reduced the consideration it had had of anti-drug policies. As for the geographical focus, already scarce reference to Latin America was further reduced as an area of critical interest for the US national security strategy. From the point of view of doctrine, an aspect that shows the greatest change with respect to the NSS document of 1999 (Clinton 1999), the thesis of preventive war was presented as the basis of the fight against terrorism. The 2006 NSS overstated the importance of Iraq as the greatest concern for national security, and barely mentioning Latin America. By 2010, the NSS timidly abandoned the Middle East and Central Asia, but to increasingly focus on East Asia.

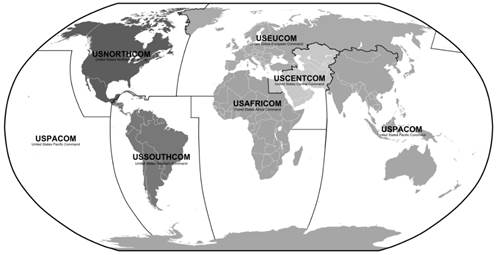

Other relevant piece of evidence of the geostrategic reorientation of the US is the relative weight of the GCCs (Watson 2011). The GCCs respond directly to US geostrategic imperatives, giving its strategists the possibility of having a structure of command, control and communications which responds to the specificities of each regional security cluster in the international system (Buzan and Wæver 2003; Watson 2011). The first two commands have their origin in the Second World War, and are associated with the principal theatres of operations, namely Europe (EUCOM) and the Pacific (PACOM). During two distinct stages of the Cold War the US created the one for Latin America (SOUTHCOM) in 1963, other for the Middle East (CENTCOM) in 1983, extended to Central Asia after the Soviet breakdown. Since 9/11, and within the War on Terror, the two latest commands were established: that of North America (NORTHCOM) in 2002, and the command for Africa (AFRICOM) in 2007 (Watson 2011). See Map 1.

Source: Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) (2018).(5) Own elaboration.

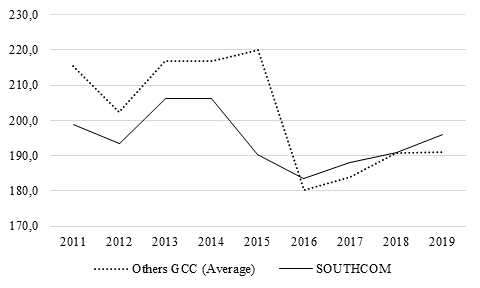

Figure 3 U.S. Geographic Combatant Commands budgets (in millions US$)

In comparative terms, the budget of the SOUTHCOM was lower than the average of others GCC (see Figure 3 above), and its role in the NSS remains stable (Watson 2011). Although the military budget data of the United States prior to the creation of the CDS are not categorized by GCC, in the transcript on the issuance of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2011, the Congressman Ike Skelton, Chairman of the Committee on Armed Services, before the imminent withdrawal of US forces in Iraq, he said:

General Petraeus [Commander of the CENTCOM], you and General Odierno [Commander of the Multi-National Force-Iraq] will have to deal with the potential instability caused by the formation of the new government and the reduction of the United States force levels simultaneously. Admiral Olson [Commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command], your forces in-country will be faced with a reduction in support from the general purpose forces, and General McNabb [Commander of the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM)], TRANSCOM with CENTCOM, will be carrying out one of the largest moves in military personnel and equipment in decades. (U.S. Congress Committee on Armed Services 2010, 1-2).

Skelton's words suggest that between 2003 and 2011, the CENTCOM forces were formidably large. In 2007 these forces in the heart of Eurasia increased because of the emerging strategy devised by Petraeus (Simon 2008). This coincides with the period of the rise of post-hegemonic regionalism and, very specifically, with the birth of the CDS.

The emergence of the SOUTHCOM in 1963 is suggestive, as it coincides with the Missile Crisis in late 1962. It served as the politico-military structure of diffusion of the National Security Doctrine for Latin America, which privileged the thesis of the internal enemy and trained the armed forces of the region in communist containment (Comblin 1989; Leal Buitrago 2003). Its relative weight was lost with the end of the Cold War and the emergence of new threats. Accordingly, SOUTHCOM assumed a predominant role in the War on Drugs of the 1990s. However, and following the trajectory drawn in the NSS documents, 9/11 events drastically changed US strategic priorities.

The creation of NORTHCOM in 2002 suggests that for the first time the NSS saw North America as a scenario of potential external aggressions and strategic deployment. War arrived in American soil. Nevertheless, the most significant change was the CENTCOM increase in budget and military capabilities. In the period of the rise of South American post-hegemonic regionalism, this command came to occupy a privileged position in the NSS, as the center of geostrategic attention. The marginalization of SOUTHCOM reached historically low levels after 2007, with the creation of the AFRICOM, reinforcing (Mackinder’s “world island” thesis 2004). The reconfiguration of PACOM from 2011, with the “Pivot to Asia” doctrine, added to the attention paid to the Greater Middle East and Africa. This process of a decade of very low geostrategic interest in Latin America allowed the rise the CDS.

Leaders adjust their discourses and agendas to their expectations, which can be grouped into fears and desires (Jervis 2015, 356 et seq.). Accordingly, decision-makers perceive in the international political reality what they expect, or fear, to see and/or what they want to see, as perception is not a passive action but an active one, in which the subject that perceives does not receive stimuli objectively, but rather recreates the perceived reality based on their expectations. South American left-wing leaders perceived that the relative contraction of geopolitical interest from the US in their region was evidence of the decline of the superpower. Despite never having experienced military intervention by US troops, unlike Central America and especially the Caribbean islands, tension related to the regional presence of the US has persisted in South America. Continuity of the Rio Pact (1947) and SOUTHCOM, in addition to the formal activation of the South Atlantic IV Fleet since 2008, stimulated leaders such as Lula Da Silva, Hugo Chávez, Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández, along with Rafael Correa, Evo Morales, and Fernando Lugo, to push for a South American mechanism of collective defense and/or deterrence.

However, it was not only the fear of losing autonomy that motivated the emergence of security regionalism. Expectations of US decline spread rapidly the academic sphere in the first decade of the 21st century (Wallerstein 2003; Haass 2008; Ikenberry 2008; Zakaria 2008; Acharya 2018). Similarly, in the plans and declarations of emerging powers and revisionist leaderships the term “multipolarity” appeared in its different meanings, both as a diagnostic and as a desirable objective by Russia, China, Iran, and Venezuela (Mijares 2017). The rise of BRICS countries, reinforce the perception of US decline.

In this scenario of perceived (or desired) US decline, not only the rivals of the superpower and South American revisionist governments diagnosed post-hegemony and the need for a multipolar world. Conservative and moderate governments, such as those of Colombia, Chile, and Peru, agreed to be part of the process of post-hegemonic regionalism, despite their good relations with the US. The discrediting of the US government under George W. Bush was the first condition for the reduction of its regional diplomatic influence. The change of administration in 2009, and the arrival of Barack Obama, made clear that Latin America was not among the priorities of the national security agenda of Washington. In the 5th Summit of the Americas in Trinidad and Tobago, Obama’s speech (2009) projected the idea of a horizontal relationship with Latin America.

In the specific case of the relationship of security cooperation between the US and Colombia, the country with the most reluctant government in security regionalism, two factors coincided. The first brought a critical juncture: the Operación Fénix (March 1, 2008) in which, through an unauthorized bombing in Ecuadorian territory, Colombian armed forces destroyed a camp of the FARC, killing Luis Édgar Devia Silva (a.k.a. Raúl Reyes), spokesman and commander of the secretariat of the guerrilla group. The operation resulted in a diplomatic crisis with Ecuador and Venezuela, with whom there was a militarized dispute, and the cutting of diplomatic ties with Quito and Caracas. Pressures from South America compelled Colombia to submit the CDS project, avoiding the escalation with Venezuela as well as the regional isolation (Ardila and Amado 2009).

The second factor relates to the cooling of relations between Washington and Bogota after the arrival of Obama to the White House. The “special relationship” of the US and Colombia (Tickner 2008), forged in the presidencies of Andrés Pastrana and Bill Clinton with the “Plan Colombia”, were deepened in the Uribe-Bush era. Both shared a similar security vision, and Colombia abandoned the term “narco-guerrilla” to use instead that of “narco-terrorism” in order to labelling insurgency (Felbab-Brown 2009). With Obama, the approach to hemispheric relations was partially de-securitized and the relative importance of Colombia in the national security agenda of the US was reduced.

Geopolitical Dynamics in South American Regionalism

While the previous two factors analyzed correspond to global effects on the region, this final factor originates in South America itself. Although the CDS does not have any institutional rival that duplicates its functions, its belonging to a larger project, UNASUR, has caused the geopolitical divisions in South American regionalism to compromise its cohesion. The failure of Brazil to consolidate its leadership in South America (Malamud 2011) meant that the geopolitical divisions of the regionalist projects should not be overlooked.

Initially, UNASUR and its CDS appeared capable of heading a different, and therefore successful, project. Post-hegemonic regionalism appeared capable of replacing the liberal regionalism of limited commitments. This was especially true of what was the definitive decline of the CAN, uncertainty about MERCOSUR, and the limitations of the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas. But the development of UNASUR, and its CDS, has suffered from fractures within South America. The biggest of these is the tension between Atlantic and Pacific. On the one hand, MERCOSUR has been experiencing disruptions due to the end of the super-cycle of raw materials and internal political tensions that have meant the end of governments affiliated with the Sao Paulo Forum, primarily in Brazil and Argentina. On the other hand, although also associated with the processes just mentioned, the political and economic crisis in Venezuela has posed a difficult challenge for MERCOSUR to overcome. Incapable of forcing Caracas to adopt the trade regulations and democratic principles of the Ushuaia Protocol, the decision made was to suspend Venezuela on August 6, 2017. For its part, the AP has manage to consolidate itself as a mechanism of economic integration that brings to mind liberal regionalism.

While the Brazilian and Argentinian governments of Michel Temer and Mauricio Macri had a markedly orientation to economic liberalization, their predecessors, Dilma Rouseff and Cristina Fernández, were the heirs of more statist models that also tolerated the authoritarianization of Venezuela. Meanwhile, the South American governments of the AP demonstrated a trend to economic opening and a democratic record which, on average, exceeds that of MERCOSUR, above all if Venezuela is included. MERCOSUR and AP are not in open opposition. Indeed, in the Southern Cone, Chile and Argentina encourage the possibility of convergence between those two regional blocs (Bernal-Meza et al. 2018). This became probable while Venezuela remains suspended from the former. However, Brazilian political instability and polarization did not allow progress in that direction, maintaining the geopolitical fracture in South America. This geopolitical division broken UNASUR, even before its dramatic split in 2018 (Mijares and Nolte 2018). This hindered even further the security dialogue between its members and affecting the performance of the CDS.

The combination of global geoeconomic and geostrategic patterns with geopolitical dynamics of South American regionalism, offers a structural analytical complement to the explanations that up to now have been given about the CDS.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that global economic (de)concentration, US geostrategic orientation, and the regional institutions geopolitical dynamics, conform a complementary set of causes for a structural parsimonious explanation about the CDS. The geostrategic over-orientation that re-emphasizes Eurasia and Mackinder’s “world island”, depending on both structural imperatives and circumstantial events. The effect of the power vacuum incentivized visible changes in foreign policies, translated into the search for greater autonomy in terms of security and defense. The arguments pose a structured explanation of South American security regionalism. This contribution is neither capricious, nor does it intend to initiate a confrontation in the structuralism/post-structuralism framework. This article contributes to widening the analytical margins toward geopolitical spaces and tools.

It also has the potential to initiate debates and open new spaces on the research agenda relating to the study of security regionalism in the Global South, and especially in Latin America. On the one hand, it sides in the debate related to (re)introduce geopolitical factors of analysis and interpretation in security regionalism, with the aim of providing structural support to its explanations. In addition, it presents arguments that could problematize North-South relations in a new context of power diffusion and changing geostrategic priorities, beyond the simplistic idea of multipolarity and the so far rigid dichotomy hegemony/autonomy. On the other hand, the research agenda that appears demands the consideration of two major aspects. The first one is the study of national decision-making processes facing the perceived changes in the international system, and the second is the possibility of generating a cross-regional traveling explanation. Both cases make necessary to take forward greater empirical and documentary research in South America and the rest of the Global South, combining the principles and tradition of regional studies, security studies, global studies, and foreign policy analysis, retaking the analytical utility of geopolitics.