Introduction.

After the setback suffered during the peace plebiscite held on October 2, 2016, the streets of Colombia’s largest cities were crowded with people demanding a final peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrilla group. It was unquestionably an unusual demonstration as Colombian society has traditionally been apathetic regarding social protests (Archila 2003). Additionally, after the failed peace negotiations initiated by the government with the FARC between 1998 and 2002, the idea that negotiation with the armed organization would provide it with an opportunity to strengthen itself militarily and territorially was a significant debate within public opinion, and ultimately circumvented the desire for peace of the government and civil society (Sarmiento and Sánchez, 2011).

Beyond the exceptional nature of these citizen demonstrations supporting the approval of the peace agreement between the government and the FARC, these social protests are considered the first to be announced, managed, and organized almost exclusively through online social networks, with participation levels not seen in the country for decades. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets and public squares in Bogotá, Cali, Medellin, and Barranquilla, as well as a dozen other smaller cities, answering the call from various activist groups using hashtags such as #AcuerdosYa [#AgreementsNow]; #PazYa [#PeaceNow]; #PazALaCalle [#PeaceInTheStreet]; and #QuieroPAZ [#IWantPEACE], which went viral on social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, and mobile apps such as WhatsApp. These actions were replicated by supporters in other cities across the globe, including New York, Paris, Barcelona, Madrid, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, and Montreal, among others. Supporters in these cities gathered as one with the protestors in Colombia.

However, the 2016 demonstrations supporting a final peace agreement in Colombia indicate an interesting collective action phenomenon, relating to one of the most intense debates in the social sciences today. The discussion revolves around the effectiveness and relevance of social movements in a social context marked by impersonal and fragile social ties (Bauman 2004), factors that imply a deterioration of contentious and radical collective social expressions. For example, “The concept of social movements, as it has been understood in recent decades, seems to break down...” (Rey 2014, 9), given that “the ways in which the parties or even the original social movements convened the protest have been misconstrued” (King 2014, 15).

Consequently, the main objective of this article is to provide evidence of how citizen demonstrations supporting the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC wielded important influence on public opinion, which was key in realizing the final peace agreement signed by the end of November 2016. With this objective in mind, this is based on the assumption that the media’s coverage of these demonstrations constituted a form of symbolic power(1) that provided the negotiations with high levels of legitimacy at their most crucial point.

This article is divided into two sections: the first briefly discusses the general characteristics of collective action in the online social era, consisting of a conceptual exercise that highlights the importance of understanding modern social movements through their interaction with the media and their processes in shaping public opinion. This exchange is decisive in understanding the case study selected. The second section deals with an overview of the main characteristics of the recent peace process and citizen mobilizations, developing the empirical research component that is used to support our initial hypothesis(2). Finally, the article presents a few brief general conclusions about the case study.

Collective action in the online social era

On the basis of the work of influential American sociologist Charles (Tilly Tilly and Wood, 2010), we know that the social movements that have spread to different parts of the world, from the eighteenth century until the present, have been characterized by the presence of three essential elements. Firstly, it is a “public, organized, and sustained effort to pass on collective demands to the relevant authorities” (Tilly and Wood, 2010, 22). Secondly, they typically involve “the combined use of some of the following types of political action: the creation of coalitions and associations for a specific purpose; public meetings; solemn processions; vigils; rallies; demonstrations; demands; statements to, and in, the public media; and propaganda” (Tilly and Wood 2010, 22), as well as “public and concerted WUNC (worthiness, unity, number, and commitment) demonstrations by their participants” (Tilly and Wood 2010, 22).

However, some experts believe that the emergence of the Internet and information and communication technologies (ICT) has increasingly turned social movements into smart crowds, a phenomenon first described by Howard Rheingold, who understood them as social settings where “individual members of each group are dispersed until mobile communication motivates them to simultaneously come together at a specific place, from all over, in coordination with other groups” (Rheingold 2004, 88). From this perspective, these types of settings “…are formed by people who are capable of acting together even if they do not know each other. Members of these groups cooperate in ways that would have been inconceivable in the past as they use very novel computer and telecommunications systems that allow them to connect with other systems in the environment” (Rheingold 2004, 188).

Therefore, a new definition for this category of social movement, adapted to the characteristics of the information society, is movements’ network, as described by Ilse (Scherer-Warren 2005), or online social movement, according to Manuel (Castells 2012).

The first term, movements network, is defined as “complex networks that go beyond empirically defined organizations and that symbolically, supportively, or strategically connect individual and collective actors, whose identities begin constructing a dialogical process” (Scherer-Warren 2005, 78-79). This process induces the construction of social identifications, which are identities for action or struggle, that is, for the specific context of the movement. These can coexist or compete with other forms of social identification (class, race, gender, etc.), and they also indicate exchanges and negotiations amid the progressive definition of an arena of struggle.

For (Castells 2012, 212-218) online social movements are characterized, among other things, by the fact that they stay connected to the network, and that the connections occur in multiple ways. They are generally both local and global simultaneously, dimensions that are not mutually exclusive. They also tend to be spontaneous and triggered by a “spark of indignation” although they may also turn to previous organizations and demonstrations to sustain themselves. In general, online social movements tend to act “virally.” They expand rapidly, both geographically and in size, all thanks to the use of new technologies.

They can be identified by their transformation of this indignation into hope, using complex symbolic and expressive forms of communication based on emotional management and mobilization. On the other hand, although they are very self-reflective, they usually lack lofty program goals and charismatic leaders, as a result of which, they tend to dissolve once they have achieved all, or a significant part of, their objectives. Therefore, online social movements tend to be nonviolent social expressions, although they often resort to peaceful civil disobedience strategies. Finally, according to Castells, like all social movements, online social movements use different “cultural shock” strategies, seeking a change in mentality. Thus, their main objectives revolve around being aware of and looking for more autonomy for subjects faced with the limitations imposed by social institutions. For all these reasons, Castells believes that online social movements are a type of collective action whose objective is “to change society’s values. It could also be a public opinion movement with electoral consequences” (Castells 2012, 217).

As well as combining coordinated actions in the search for specific political aims through different forms of demonstrating worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment (“WUNC”), actions that may otherwise be undertaken through different information channels and with different action repertoires (face to face, and/or virtually). Is clear that the dynamics of social movements, and how they function, cannot be understood outside their recurring intention to impact the sphere of public debate, which has been one of the most relevant and frequent characteristics over time (Tarrow 2004, Neveu 2006).

Therefore, it is useful to remember that Castells believes social demonstration in the online society era to have been characterized by a complex mass self-communication process, defined as a form of communication that “can potentially reach a global audience” (Castells 2009, p. 88). These forms of communication must be understood as “…self-communication, as each person creates the message, determines the potential recipients and chooses the specific messages and content from the web and electronic communication networks that they wish to retrieve” (Castells 2009, 88).

Thus, it should be noted that this type of communication coexists with and replicates itself through traditional means of communication, that is, individual and mass communication. This is the case despite the vast amounts of contemporary research on social movements that seek to identify how they interact with digital social networks and ICT in general as a preferred form of mass self-communication (Castells 2009).

Accordingly, this article argues that the types of interaction between social movements and the media are not exclusive dynamics as other experts have argued (Gamson et al. 1992, Koopmans 2004, Snow 2007). These modes of interaction reproduce patterns of prestige and preferential framing, impacting how the movement is perceived by the rest of the political community, and generating sympathy, to a lesser or greater degree, from the public.

Hence, along with (Koopmans and Olzak 2004), we accept that there are few social protest strategies and demonstrations that capture the media’s attention, and that the processes of disseminating information that identify the dynamics of how the media covers social movements are characterized by configuration of discursive opportunity structures, which only allow certain situations, messages and demands to benefit from the media’s mass broadcasting. Thus, it is crucial to consider the visibility, resonance and legitimacy that the media bestows upon the actions and demands of social movements.

Visibility is understood as a message’s ability to influence public discourse, as well as the media publishers’ ability to make this message influential on the basis of the number of times (frequency) the message is spread or repeated (Koopmans and Olzak 2004, 203). Resonance must be interpreted in two ways: as a reproduction, or partial reproduction, of the message. This is because media producers view the message as more important than the person who conveys it, thus looking for other actors or people of influence to talk about a particular subject or demand. However, it is necessary to specify that reproducing the message or demand of the social movements can be advantageous, that is, resonance, or in the case of a negative or partial reproduction of the message or demand, this represents dissonance (Koopmans and Olzak 2004, 204). Finally, and most importantly, legitimacy is defined as the average reaction of actors in the public sphere, which can be used to identify whether these actors support the claims or demands of the social movement, or whether negative reactions, or those against the movement, are more common. This accounts for the positioning of the actions and demands of the social movement being covered by the media (Koopmans and Olzak 2004, 205).

While we acknowledge the complex involvement of activists in supporting the final approval of the peace agreement and in using ICT as a form of mass self-communication, we assume here that it was a tool to organize and manage the protests, with the goal of holding massive demonstrations which would render their demands more visible. Thus, in this research we followed the official Twitter accounts for nine of the most influential Colombian media outlets. As a result, we built a database to record the news published on the peace process between January 2013 and December 2016. Based on this set of news stories (more than 15,000), we selected pieces that specifically referenced the mobilization for or against the agreements when they received media attention.

To systematize this information, we designed a matrix to categorize the news events, differentiating the information bias as negative, neutral, or positive. We also categorized the actor, or actors, involved in the news and the media bias toward each actor’s actions or opinions.

The media outlets we analyzed were the national newspapers El Tiempo and El Espectador; El Colombiano from Medellin; El País from Cali; the magazine Semana; and the TV newscasts Noticias Caracol, RCN Noticias, and CM&. For audio communication, the only media outlet included was W Radio because, unlike others, its audience covers most age groups. It is important to mention that the media outlets with the most Colombian followers on Twitter are Noticias Caracol and RCN Noticias.

The information held in this database is expected to account for the media positioning received by the citizen mobilizations related to the peace process between the Colombian government and the FARC. This article demonstrates how these protests increased the legitimacy of the negotiation process. In doing so, this analysis concurs with the perspective that legitimacy is a determining factor in the success of peace processes (Stedman 1997, Elorriaga 2017). Simply put, this means that a good part of that legitimacy should be understood as a form of symbolic capital or power, framed within the dynamics that form the social sphere of public opinion (Grossi 2007).

The peace process and citizen mobilizations to achieve a final agreement

As some studies have observed (Charry 2018), the process of negotiating a peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC was characterized by “highs” and “lows”, particularly when considering how the media presented information on the progress of the negotiation. In this sense, there were three general types of media framing.

The first, used at the beginning of the negotiations, tended to associate the peace process with what happened in the failed negotiations of San Vicente del Caguán, during the administration of Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002). There was then a transition between this manner of representation to the second, in which discrepancies between President Juan Manuel Santos and former president and then-Senator Álvaro Uribe Vélez prevailed. This dispute was based on how the internal armed conflict should be resolved: Santos was guided by a policy based on military pressure amid negotiations, whereas Uribe Vélez insisted on military pressure as a mechanism to force the armed group to be brought to justice. These differences over how to resolve the internal armed conflict began to take on greater ideological, and specifically partisan, overtones, marking the third type of media framing. This eventually provoked the use of extremely polarizing expressions during public discussions about peace negotiations, thereby dividing the public, and with it a notable number of voters, into two opposing groups: opponents and supporters of the peace agreements.

Throughout this process, it became clear that the ideological and political polarization was largely the product of an electoral debate for bureaucratic control of the State, connected to the mid-2014 presidential elections. In this election, the incumbent president Juan Manuel Santos won more than a million votes more than his rival candidate Oscar Iván Zuluaga, the representative for the political groups that objected to the negotiations, even though Zuluaga had narrowly won in the first round.

Likewise, it became clear that the stories that took precedence in the media’s coverage of the peace process were primarily focused on daily updates regarding the negotiations, leaving aside the deeper content of what was under negotiation; that is to say, the media was guilty of missing the woods for the trees. The media also gradually introduced a fourth type of framing related to the possibility of an abrupt breakdown in the negotiation process. This was represented intermittently, after kidnappings, the FARC’s alleged violations of the unilateral ceasefire and other violent events that occurred during the talks, in addition to instances when statements made by detractors of the process were presented, with opponents of the negotiations making repeated use of this framing method (Charry 2018).

For this reason, the media was able to introduce in their coverage a set of issues that were very different to those being negotiated in Havana, and it was clear that, in this case, there was no consistency between the agenda of the negotiations and the agenda of the media. On the contrary, what occurred was the overexposure of the media agenda compared to the agenda in Havana, creating a situation in which high-impact political events that could threaten the achievement of a final agreement, most of which were far from what was happening in Havana itself, as well as the political controversies that arose from these events, were the ones that ultimately won out and dominated the information agenda. In the same way, the aforementioned study also observes that (Charry 2018), despite overall coverage in favor of the agreements, there were some short-term critical moments when the media expressed a negative view, or one against the process. It is evident that as early as January or February 2015, the forms of framing and presenting the news varied mainly between positive and negative headlines, meaning that this polarization displaced information objectivity and neutrality. It was found that the Colombian media system was divided into two large groups. The first group expressed strong support for the agreement (represented by El Tiempo, El Espectador, W Radio, and CM&), while the other group was more skeptical and showed less support (including Noticias Caracol and RCN Noticias; El Colombiano from Medellin; El País from Cali; and the magazine Semana) (Charry 2018 124-126).

Throughout the four years of negotiation, there were three decisive moments for social protest demonstrations. The first occurred in 2013, when, due to a complex convergence of interests, President Juan Manuel Santos and then mayor of Bogotá, Gustavo Petro, held a rally together in support of the peace agreements on April 9, the Colombian National Day to Commemorate Victims of the Armed Conflict. The country would have to wait more than three years to witness a new round of protests, which occurred on August 10, 2016. Finally, the third round of protests took place after the “NO” vote, against the peace agreement, in the plebiscite on October 2, 2016.

Apart from the temporal differences in which they developed, each round of protests that marked the development of the peace negotiations and agreement also had very distinct objectives. First, the demonstrations on April 9, 2013, were coordinated by diverse political organizations. These included the Polo Democrático Alternativo political party, the Marcha Patriótica movement, trade unions such as FECODE and CUT, and the Bogotá Mayor’s Office, as well as parties and political movements close to President Juan Manuel Santos. These include sectors of the Partido Liberal and the Partido de la U, as well as certain members of the Partido Conservador and Cambio Radical. It was, therefore, clear that the goal of these demonstrations was to support the peace negotiations, which were heavily criticized by political opponents of the Santos government. These opponents argued that after six months of negotiations, no significant progress had been made, even though the guerrilla group had complied with a first unilateral ceasefire and incorporated new members into their negotiating delegation, such as Pablo Catatumbo (an alias), intended to send a message of unity and cohesion within the organization, and which also led to a significant decrease in confrontataions and violent deaths.

In contrast, the protests held in August 2016 were the result of other interests coming together, including the rejection of the Santos government and his administration’s main policy: the development of the peace agreements. However, these social protest demonstrations were held in the context of the consolidation of the peace negotiations, which were showing signs of imminent success in reaching a final agreement. We refer to acts such as the “legal shield for peace” in June 2016, added to the announcement made by the negotiating parties which indicated that they had reached an agreement on the highly challenging third point of the talks, related to the protocols that would be followed for the final ceasefire. And it was in this context of consolidating a favorable image of the agreements that opponents announced a call for a national rally against what they called “gender ideology.”

These sectors were led by Alejandro Ordóñez, former State Attorney General, and supported by one of his main political allies, Ángela Hernández, a representative from the Department of Santander. Ordóñez and Hernández repeated a series of concerns expressed by a major parent association group, some evangelical religious congregations, and, to a lesser extent, Catholics, who rejected the disseminating of sex education pamphlets, designed by the Ministry of Education and supported by the United Nations, in primary and secondary schools. However, the leaders of these rallies believed the true intention of these pamphlets to be the introduction in schools of an ideology that would completely change the roles traditionally assigned to men and women, and thereby turning on its head the concept of families, adoption, and marriage (Beltrán and Creely 2018).

Opponents of the negotiations, and of the government, strategically capitalized on this argument to shift the public debate at a time when a final agreement with the FARC was about to be reached. To that effect, the organizers of this round of protests were responsible for spreading the idea that the “gender ideology” they saw in the Ministry of Education’s pamphlets was equivalent to the “gender-sensitive approach” promoted by the negotiating parties of the peace agreement. The negotiators true objective was to give specific, specialized attention to the sector of the population that had suffered most from the destruction caused by the Colombian armed conflict: women. Based on these precepts, what was initially considered a protest against sex education pamphlets became a protest against the peace agreement being negotiated in Havana, given that these protestors believed the peace agreement was going to have direct constitutional consequences on concepts they claimed to defend, and therefore, they demanded that the agreement also be rejected (La cartilla de orientación sexual, 2016; Marchas en el país contra Mineducación, 2016).The third and longest protest cycle started to take shape on the evening of October 2, 2016, when the results of the plebiscite were informed in record time, with the number of “NO” votes slightly leading those for “YES”. The outrage began with a feeling of uncertainty, given the marked advantage for the “YES” vote shown in polls prior to the plebiscite, favoring approval of the agreement, something which may have caused a counter-productive effect by causing the constituencies that supported the peace agreement to relax. However, in a rapid, strongly-worded announcement, the FARC stated that they would not relinquish the idea of achieving a final agreement. For their part, some sectors of the political opposition requested that the negotiating parties continue seeking a more convincing agreement, while other, more radical, sectors insisted that the right thing to do was to resume unrestricted warfare against drug-related terrorism, the main representative of which was the FARC. Meanwhile, the government could not find a better option than to accept the result of the plebiscite and announce that it would become involved in a series of high-level meetings with the “NO” leaders and the remaining political parties, all this with the purpose of finding possible solutions to the political and legal conflict involving support for the agreements.

Amid the bustle of opinions and announcements, a group of young people called for protests to take place on October 5, to demand a final peace agreement. The motto of said protests was simple and forceful, expressed with a simple hashtag: #AcuerdosYA, or, #AgreementsNOW. These symbols became the leitmotif of an entire generation of Colombians who grew up watching through the media an armed conflict that was deployed hundreds or thousands of kilometers away from the cities where they live(3).

Unlike the two prior protest cycles, the organizers of which were closely linked to fully constituted political parties and movements, the leaders of this new cycle were a diverse group of young university students, mostly from the Broad National Student Council (Mesa Amplia Nacional Estudiantil, MANE, for its Spanish acronym), which had led important social demonstrations against the attempt to reform the National Education Act in 2011. Other organizations joined these groups of students, with liberal professionals, artists, and intellectuals coming together and congregating in so-called “citizen town meetings”, which had a certain level of validity and coordination in some central neighborhoods in Bogotá, and to a lesser extent in other cities, such as Cali, Bucaramanga, and Pereira.

To achieve mass mobilization, and in an attempt to put pressure on the government to continue seeking a negotiated solution to the armed conflict, the youth-led movement called this first mobilization the Third March of Silence, in commemoration of that undertaken by Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and the movement he led in the mid-1940s against the partisan violence that was beginning to occur in the nation. According to some of the protest leaders, the objective was to make use of social networks to recruit a high number of people who would peacefully demand the signing of a final agreement, regardless of their political or ideological differences. This strategy was successful as they were able to gather around 70,000 people in Bogotá alone, crowding together in the Bolivar Square and its surroundings, entirely blocking the city’s downtown, and catching the attention and coverage of the most influential national and foreign media(4).

Profiles were created on social networks, such as Paz a la calle (Peace in the streets), PazSiempre (Always Peace), as well as hashtags like #AcuerdosYA (#AgreementsNOW). Instructions were sent to demonstrators to bring white flags and to march in complete silence, which were strictly followed. Demonstrators could also check in real time the meeting points and the routes that would be taken to arrive at the final destination. Everything suggests that the level of coordination achieved was flawless, as the protests were completely orderly and peaceful. This contradicted historical trends that included detours through unauthorized routes and altercations with the squadron of anti-riot police at the end of any given protest.

The call for a second protest joined this initiative and was scheduled for October 12. This time, the coordinators named it the March of the Flowers and asked the demonstrators to wear white t-shirts and carry lit candles and white carnations as symbols of peace and reconciliation. Once again, the level of coordination between the organizers and demonstrators was excellent. However, the coordinators took this opportunity to extend a special invitation to peasant, Afro-descendant, and indigenous communities affected by the armed conflict to march and take over the Bolivar Square. The spatial arrangement of this protest acquired a deep symbolism, which must be understood as a type of repertoire in itself, as the first people to arrive in the Bolivar Square were university students who partially filled the square and formed an honor guard to welcome the invited peasant and ethnic communities as a sign of respect, seeking the (symbolic) reconciliation of two countries that had been historically disconnected: the rural and the urban.

Together with the messages of reconciliation, different musical and artistic groups joined the demonstration, thereby making this act a democratic celebration, and the public square a privileged space of political deliberation. The emotiveness and eloquence of the demonstrators were transmitted to an endless number of bystanders who watched from different buildings and rooftops, shaking their white handkerchiefs and Colombian flags as a way of expressing their support and sympathy for the demonstrators’ objectives. Support for the protest’s purposes reached such an extent that the Colpatria Tower, an emblematic skyscraper in downtown Bogotá, illuminated the building with lights simulating the Colombian flag and the white flag of peace (see Photographs 1 and 2). This series of actions was replicated in dozens of other cities, thus forming a wide network of demonstrations and demonstrators who coordinated their actions with the sole purpose of finding a definite and peaceful outcome to the armed confrontation. Thereby, they went beyond the geographic obstacles and the regional and ideological differences that have characterized Colombian society (“Miles volvieron a marchar en Bogotá” 2016).

Source: Own elaboration.

Photographs 1 and 2 Facade of the Colpatria Tower and peace mobilizations. Personal Files, October 12, 2016.

In an attempt to replicate the success of prior protests, those in favor of a final peace agreement called for a third demonstration on October 20. Emulating the same strategy, the demonstrators were asked to take white flags and t-shirts to the demonstrations in the different cities. However, this time, the repertoire of action introduced a small innovation: when the demonstrators arrived at their meeting points, they had to form a huge circle simulating the negotiating table, and then, in complete silence and darkness, each demonstrator would turn on the light of their cellphone. The intention was to send a message to the negotiating parties: that it was possible to find “the light”, to reach a final peace agreement without further extensions or delays.

Despite registering significant attendance, both in Bogotá and other cities of the country and the world, a decrease in the number of demonstrators could be observed, associated with a series of facts that showed the demonstrators’ demands for peace were starting to be considered and implemented by the representatives of the institutional political system. Therefore, this appeased the charged climate of public opinion created by the protests, which demanded the making and/or authentication of a final agreement. This situation would be confirmed further with the call for a new protest in the first days of November, which again had a significantly reduced attendance.

In fact, several days before this, President Santos himself had welcomed the leaders of the protests to the Casa de Nariño. There, they had the opportunity to express their concerns, as well as their expectations, on the paths that should be followed to ensure agreement could finally be reached. Additionally, the government had initiated a strenuous series of meetings, both with those opposing the negotiations and with organizations of victims and citizens groups, with whom the government tried to identify the modifications that should be introduced to the agreement reached in Havana. That was the reason why one of the groups organizing the protests opted to maintain the peaceful occupation of the Bolivar Square, where nearly one hundred young people set up camp as a sign of expectation and vigilance until the signing of the final agreement was achieved, another action that captured the attention and coverage of the media.

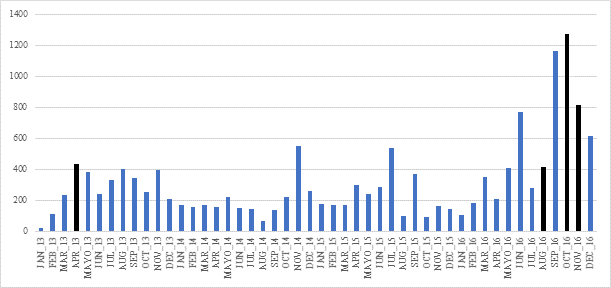

However, it is important to ask: what were the consequences of those diverse social protests? What degree of visibility, resonance, and legitimacy did they obtain from the media? Based on the information in the database created for this analysis, we can observe that of the nine months in which the media presented more than 400 news events, four of those relate to the months in which the marches in favor of, and against, the peace agreement took place, highlighted in bold in Chart 1.

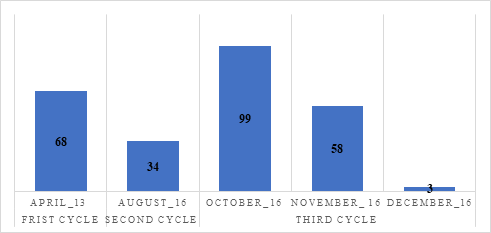

Although this indicator shows all news events related to the peace process month by month, the evolution of news exclusively related to the citizen mobilizations carried out in the context of the peace process can be identified in Chart 2. It shows that the third protest cycle, associated with the protests organized by young people demanding the signing of a final peace agreement, had much longer impacts, continuing its media visibility through the months of November and December 2016. On the other hand, the effects of the other protest cycles were not covered by the media after the month (or the week) in which they took place. However, data shows that the greatest visibility was associated with the protests held in October 2016, while the least visible was that which took place in August of the same year, that is, during the second protest cycle.

In fact, from the volume of news per protest cycle, it can be noted that the third cycle obtained 160 news events, meaning it had 2.3 times more visibility than the 68 news events obtained during the first cycle, and 4.7 times more visibility than the 34 news events presented in the second cycle. This demonstrates the media visibility acquired by the citizen mobilizations in favor of a final agreement.

Source: Own elaboration

** Frequency of news events on citizen mobilizations around the peace process)

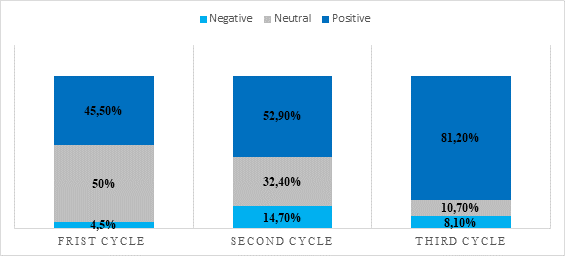

With regard to information bias, which allows us to assess the resonance and/or dissonance resulting from the news on the collective actions in favor of, and against, the peace process, by classifying the media framing of the news headline into “negative,” “neutral,” and “positive” (depending on the adjectivization in each headline) (Van Dijk 1990 and 1997), one can also infer the “closeness” or “distance” of the news to the demonstrators’ instructions and messages had in each case.

Accordingly, it was found that in terms of information volume, the highest negative bias (14.7%) was associated with the second protest cycle, while the highest positive bias (81.25%) was related to the third cycle which, at the same time, had the lowest neutral bias (10.7%). Such a framework refers to news events, the only mission of which is to inform, without evaluating or assessing the objectives and demands of the protests or the demonstrators (see Chart 3). This allows the assumption that the third protest cycle was much more effective and successful in its media positioning.

Source: Own elaboration.

Chart #3 Distribution of the information bias in citizen mobilizations around the peace process

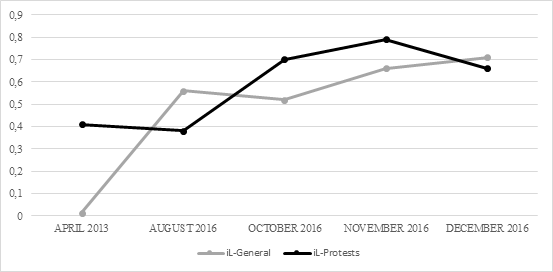

Finally, the legitimacy index allows for the identification of the global media positioning of each protest cycle and its impact over time. As shown in Chart 4, the gray line stands for the legitimacy index for the entire set of news events concerning the peace process for each month during which the protests took place (or iL-General, for its Spanish acronym), whereas the black line refers to the evolution of the legitimacy index obtained regarding the set of news events associated exclusively with the protests (or iL-Protests). It is worth mentioning that, unlike bias (or resonance), the legitimacy indicator (or iL, for its Spanish acronym) is calculated by dividing the difference between the positive and negative frameworks by the total number of news events related to a given topic. This allows for the assessment of its global variability without considering the normalization that the neutral bias may bring in (Koopmans and Olzak 2004, Muis 2015)(5).

Source: Own elaboration.

Chart #4 Evolution of the legitimacy index -iL-. Media coverage of the citizen mobilizations around the peace process

Table 1 Evolution of the legitimacy index -iL-. Media coverage of the citizen mobilizations around the peace process

| Month | iL-General | iL-Protests |

|---|---|---|

| APRIL 2013 | 0.014 | 0.41 |

| AUGUST 2016 | 0.56 | 0.38 |

| OCTOBER 2016 | 0.52 | 0.7 |

| NOVEMBER 2016 | 0.66 | 0.79 |

| DECEMBER 2016 | 0.71 | 0.66 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Therefore, it can be seen that the lowest legitimacy index was shown during the second protest cycle of August 2016. At that juncture, a significantly open difference is observed in favor of the general legitimacy index, clearly showing that the difference observed in the month of December 2016 was too small (barely 0.05) for it to be considered a significant difference.

At the same time, one can highlight that the months of October and November 2016 were the moments in which the legitimacy index of the protests was at its highest point. Thus, we can assume that the media coverage of the protests in favor of the implementation of a final peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC contributed to the sustained increase in the general legitimacy index associated with coverage of the peace agreement. This can be observed in the table attached to Chart 4, where the general legitimacy index rose from 0.52 in October to 0.66 in November, and finally to 0.71 in December 2016. During these three intense months, the peace process went through the loss in the plebiscite and the demonstrations called by young university students demanding a final agreement, in addition to the renegotiation and preparation of the new agreement, which would subsequently be endorsed by the Congress of the Republic in December of that year.

Conclusions

On the basis of the information in the database created for this analysis, it was possible for us to verify that the media positioning of the citizen mobilizations in support of a final peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerilla group was not only more visible and favorable, but also much more effective and legitimate. However, so far, this research has not included evidence based on the discursive expressions related to such social protest marches, which include pictures and video clips showing the massive protests and citizen gatherings that took the streets of the main cities across the country, being tools which bring with them very different signs of relevance or importance to a news story that includes only text (Gamson et al. 1992).

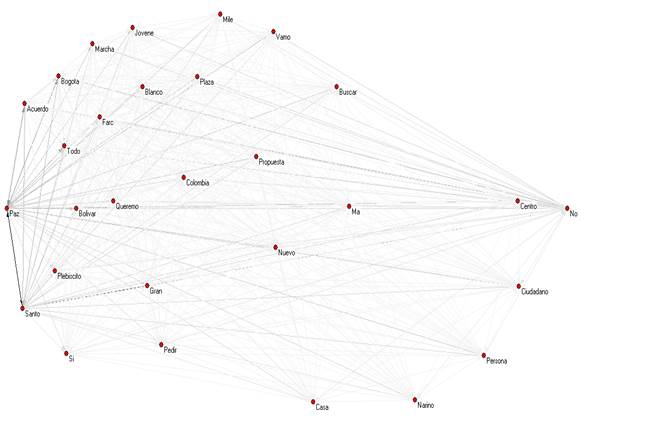

On the other hand, on the basis of a semantic association network analysis (see Chart 5), which allows us to observe the most used words by the media and their contextual relation or association, it is possible to identify the significant or meaningful structures created by the media, structures they used in an attempt to project a specific image or representation about this series of citizen mobilizations.

To this end, we considered the headlines associated with the marches held in 2016 in favor of a peace agreement, broadcast by the media with the greatest influence and coverage, both because they presented the highest volume of information and because they had the highest number of followers (or the largest audience)(6).

Noticias Caracol and RCN Noticias were taken as references. The words they most commonly used to refer to the citizen mobilizations form a network of closely linked concepts, which ranges from the word “peace” to “agreements,” “Santos,” “Bogotá,” “young people,” “protest,” “square,” “Bolívar,” “white”, “great,” “yes”, “we want,” “thousands,” “ask,” “proposal,” “new,” and “more,” among others. This vocabulary makes reference to an exaltation discourse, by using adjectives that favorably projected the objectives and demands of the demonstrators, such as “great,” “thousands,” and “more.” This element allows us to confirm our initial hypothesis, that the media coverage associated with these protests became a form of symbolic power that would be key (although not definitive) to the achievement of a final peace agreement, by its association of the protests’ citizen mobilization actions with the notion or idea of “peace,” placing this concept as a necessity, or higher good, for Colombian society, represented by the word “Colombia.”

Source: Own elaboration.

Chart #5 Network of semantic association regarding protests in support of the final peace agreement.

By taking in isolation some of the headlines used in this analysis, from different media sources, it is possible to identify the discursive construction of exaltation to which we have referred, and which is expressed by the use of adjectives such as “massive,” (see Image 1). The second headline shows that the media gave strong resonance to the objectives of the protestors, by relaying their demands in an emotive manner that implicitly screamed “choose peace,” as can be noted in the signs and the clothes worn by the protestors (see Image 2). It is particularly clear that in both cases, the use of photography was decisive as it was used to associate the gatherings of people, who, in a coordinated and stoic way, had taken to the streets to lay claim to a common and higher good for all Colombian people: peace. This message was expressed through the white flags carried by demonstrators and intertwined with the national flag.

Source: https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/paz/asi-transcurre-marcha-del-silencio-paz-galeria-658793)

Image 2 Headline- El Espectador, October 5, 2016.

If we propose a counterfactual scenario that allows us to consolidate our evidence(7), it is helpful to think about what would have happened if the protests held in October 2016 had been against the signing of a final peace agreement, or if these had demanded the definitive end of negotiations. This was the case of the protest cycle in August 2016, which had an effect on the plebiscite that made it possible for the “NO” votes to defeat the “YES” votes by a narrow margin (Beltrán and Creely, 2018). In the same vein, it would also be relevant to ask whether the government, and the negotiations with the FARC in and of themselves, would have had sufficient symbolic capital to convince the political parties to initiate some tough, complex, and questionable renegotiations, and even more, to have the new agreement endorsed by a majority in Congress (which indeed occurred), if the massive marches held in October and November 2016 had demanded the definitive termination of the negotiations, and with that, the end of the opportunity to achieve a final peace agreement.

Because of these elements, we believe that if the protest cycles calling for a final peace agreement after the defeat in the plebiscite of October 2016 had not taken place, there would have been an increase in the illegitimacy indexes in the dynamics of public opinion formation regarding the peace agreement reached. Therefore, its final authentication would have been even more controversial, questionable, and traumatic than it was in reality.

To conclude, it is important to highlight that the citizen mobilizations in support of a peace agreement in Colombia in late 2016 represent part of the wider transformations within the Colombian social structure since the dawn of the 21st century. This is not only due to technical innovation, expressed through the use of the new information and communication technologies, but also because these forms of collective action follow a different way of understanding social protest. This is not necessarily linked to a well-established or widespread organizational militancy, as such demonstrations were led by an undifferentiated group of young people from different socioeconomic levels without a clear party affiliation. Their single objective was to achieve a peace agreement, emulating and deepening the organizational strategies and innovation in the repertoires of action implemented years earlier by the movement against the 2011 higher education reform (Barón 2018).

In fact, the idea underlying these methods of collective action is that to achieve the desired change, it is not enough only to direct one’s demands at the powerful and to catch their attention. It is also about significantly impacting the processes of public opinion formation, making the different media a potential and strategic ally. With that, the activists of these methods of social protest have attempted to leave behind the old, one-dimensional, and mechanistic vision of the mass media. Through such archaic depictions, they were perceived as a simple reproducer of the established social order and had the makings of becoming an obstacle for the demonstrators’ objectives and demands.

However, with regard to the mass social mobilizations, developed in real time from different points of the national and global territory, the activists in favor of the peace agreement of 2016 proved that with highly emotional and symbolic content expressed in narratives much better connected to the demands and expectations of the new generations of Colombians, most of them being young people in urban areas, and therefore much more related to the sociocultural dynamics at the global and transnational levels, it would be possible to achieve an important change in the imaginaries and representations of the other actors of the political community. With that, they aim to raise awareness and broaden the horizon of interpretations of what was happening at that time in the country.

These elements become more relevant if we consider the fact that the collective actions for peace presented until that moment in Colombia had been characterized as self-expression by ethnic communities (indigenous and Afro-descendants) and peasants who had been directly affected by the armed conflict (Hernández 2007; Quiceno 2015) or by urban sectors tired of the terrorist actions employed by illegal armed groups (Romero 2001) without achieving a real and effective articulation between such groups of social protestors (García-Durán 2006, Rueda, 2015).

That is to say, perhaps one of the most outstanding achievements of the spontaneous and massive citizen mobilizations in support of the peace agreement in October and November 2016 is that of finding the correct framings (or frames) for the political and discursive opportunity structure being shaped in the country (many of which were summarized in a single hashtag). This was possible by employing the appropriate information channels, and action repertoires to spread the objectives and demands of the movement and subjecting them to the approval of a much wider and more complex political community. With that, citizen demonstrators were expecting to overcome the ethnic, religious, and social class cleavages that characterize the complex composition of modern Colombian society. This topic should be further investigated regarding the forms of collective action and social protest occurring throughout the country, with the future in mind.