Introduction

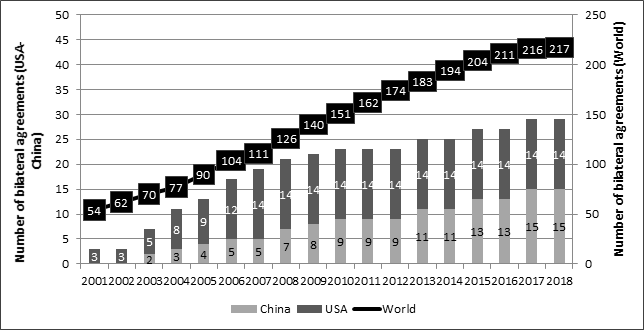

The multilateralism-regionalism dichotomy has been a matter of controversy in the international trade system since the first attempts at a unified continental Europe. While the formation of regional trade blocs in the 1990s has been accompanied by the reduction of tariff and non-tariff barriers in multilateral agreements, the following decades saw multilateralism stagnate in favor of bilateral agreements - the duration of the Doha Round by itself exemplifies the obstacles in facilitating open global trade. On the other hand, literature shows that many countries have opted for a bilateral approach for agility in negotiations, and the higher control over profits and losses stemmed from its commercial modus operandi. The beginning of the 21st century saw not only a rapid increase in bilateral agreements but also a decrease of new regional agreements, along with a heightened distrust regarding the prospect of multilateralism. According to the WTO, the number of bilateral agreements between countries has risen from 54 in 2001 to 217 in 2018. Furthermore, the experience of international investment treaties has been mostly at a bilateral level, which explicitly shows the advantages in negotiating specific deals between two parties (Allee and Peinhardt 2014).

The rise in bilateral agreements over the last two decades can be mostly credited to the strategies of the world’s two largest economies: China and the US. Here, the US takes the first-entrant role - all of its current fourteen treaties were signed before 2007. China, in turn, is the latecomer, with only five treaties (out of a current total of fifteen) ruling prior to 2007. We argue, in this paper, that both countries’ recent conversion to bilateralism might be attributed to the advantages in the asymmetry intrinsic to a two-way agreement between a large economy and a small one. Indeed, based on an equilibrium model of trade agreements, Saggi and Yildiz (2010) point out that heterogeneity across countries - concerning their endowments and, therefore, to the size of their economies - leads to a free trade environment at the world level only if countries opt for bilateral trade agreements.

Hence, the objectives of the study hereunder are to analyze the characteristics and the relationship between multilateralism, regionalism, and bilateralism and to examine similarities and disparities of China’s and the US’s experience in bilateral agreement initiatives, emphasizing the role of asymmetry between these two large economies and their partners. We follow an analytical approach to deal with trade agreement definitions and descriptive analysis to characterize the Chinese and the US experience. As for the remaining sections of this paper, we review the main conceptual paradigms concerning lateralisms in section two. In section three, we discuss how the three forms of trade integration relate, theoretically, to each other. In section four, we analyze the main underlying economic and political traits of the bilateral trade agreements signed by China and the US. Lastly, in section five, we discuss the conclusions of our study.

A Brief Taxonomy of Lateralisms

During the 1930s, the increase in unilateral import tariffs (like the Smoot and Hawley tariff in the United States), along with domestic currency devaluation strategies (the infamous “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies), heavily impaired international commerce and deepened the recession (Irwin 1998). These disastrous monetary and commercial steps taken in the years of the Great Depression later pushed countries toward multilateral integration policies following the fallout of World War II. At this time, the Bretton Woods Agreement innovates the international economic system with the establishment of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the International Trade Organization (ITO). Due to the political principle that trade liberalization should be subjected to economic development goals, the US did not adhere to the ITO, hampering its formation. Conversely, most post-war nations acknowledged the need for institutional support to foreign trade initiatives, resulting in the signing of the General Agreement of Trade and Tariffs (GATT) by 23 countries in 1947. Despite being more restricted than the ITO, the GATT rapidly spearheaded the global process of multilateral trade opening, primarily through the promotion of trade rounds (Crowley 2003). Lastly, the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 cemented the multilateral liberal strategy by linking trade barrier tax deduction to the economic growth of its member countries. Multilateral trade has since evolved directly from the system negotiated within the GATT/WTO, its regulatory framework, advancements, and setbacks. Although multilateralism remains the principal trade stimulus strategy among WTO members, regional forms of liberalization with limited regional reach gained traction since the 1990s (Schiff and Winters 2002).

Diverging traits of the various forms of lateralism call for a taxonomical analysis; we briefly discuss three of these different definitions and argue for the use of the third one: (i) Bhagwati and Panagariya’s (1996) traditional argument regarding the multilateral/regional controversy; (ii) the WTO’s operational definition; and (iii) the definition proposed by Renard (2016).

According to Bhagwati and Panagariya, regional integration initiatives are deals that usually have preferential tariff treatment for groups of countries that share geographical proximity, although this need not be the case. Preferential tariff treatment, however, is a defining trait of regional deals: trade between recipient countries incurs a lower rate - called the Most Favored Nation clause (MFN) - in comparison to trade with outsider countries. Bhagwati and Panagariya (1996) argue that the non-discriminatory nature of such commercial integration (all participating countries share the same trade privileges) reduces trade barriers, making the MFN clause compatible with universal, multilateral trade liberalization.

As stated in WTO (2018) classification, there are two distinct groups of non-multilateral trade deal types: regional deals, which include Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and Custom Unions (CUs); and Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs). FTAs and CUs are mutual deals among two or more partners (in CUs particularly, trade with non-members incur a common external tariff), whereas PTAs are unilateral trade advantages, non-reciprocal in nature, as exemplified by the General System of Preferences. The traditional approach fails to address the recent rise in bilateral trade deals, which calls for a classification method that encompasses and distinguishes older regional commercial integration forms mentioned and newer two-country deals. The taxonomy used in this paper was adjusted according to Renard (2016) and recognized multilateralism, regionalism, and bilateralism as three distinct scopes of cooperation within the international trade system. Multilateralism is used as described by the WTO: universal multilateralism, reaching every member country equally. Regionalism is defined as a plurilateral pact involving three or more countries, which are usually geographically close. Bilateral deals are those between two countries, contiguous or not. Only reciprocal deals were considered for this study. Regarding regionalism and bilateralism, inter-regional agreements between two or more countries are considered in our methodology. Finally, we ruled out plurilateralism, which refers to agreements among three or more countries given a choice to agree to the treaty rules voluntarily. Plurilateral deals are too specific and are usually applied to restricted fields such as information technology and financial services.

The Relationship between Multilateralism, Regionalism, and Bilateralism

The relationship between the different forms of commercial integration has been the subject of studies that focus on the historical, political, and development point of view (Mansfield 1998; Teló 2007), and that raises the question of whether, and to what degree if so, these processes complement or substitute one another. To answer this, one may look back to when multilateralism had its principles and rules first established, as well as the rise of regional and bilateral initiatives.

From a historical standpoint, the controversy on the form states choose to coordinate their international behavior has consequences in dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security. According to Hummer and Schweitzer (1994), regional arrangements or agencies pose a constraint or a means for the United Nations, for instance, to appropriately design action plans to achieve its purposes and principles. Based on an international relations perspective, Ruggie (1992, 568) argues that multilateralism “refers to coordinating relations among three or more states under certain principles” and therefore, surely, multilateralism opposes bilateralism. In addition to that, the author points out that by acting within multilateralism principles, states produce a wide range of mutual benefits in the form of diffuse reciprocity. At the same time, bilateralism is based on compartmented relations, with specific reciprocity resulting in a power balance between the two parties.

Multilateralism was formally constituted with the Bretton Woods agreement and the subsequent creation of international organizations such as the GATT, the World Bank, and the IMF. The trading system evolved and expanded with ensuing Negotiation Rounds and had its apex after the Uruguay Round, culminating in the founding of the WTO in 1995. Since 2001, however, there have been difficulties in closing the Doha Round in Qatar, openly indicating a stagnation of multilateralism. Negotiations during this Round had the burden of its ambitious opening goals (compared to earlier Rounds) and were further hampered by the many crises in the following years (like the 2007-08 international financial crisis). The Doha Round’s closing delay, which made it almost twice as long as the Uruguay Round (itself the second-longest, having lasted from 1986 to 1994), brought criticism to the WTO’s negotiation rules, such as the restrictions to reviewing opening Round goals and the Single Undertaking principle (Schwab 2011). This, in turn, coincides with the expansion of non-multilateral commercial agreements, especially bilateral ones.

Despite this recent shift in predilection, regionalism still has its multilateral roots, and thus the last seventy years have seen at least two waves of bloc formations (Wunderlich 2016). The first European deals are signed starting in the late 1950s (after Benelux in 1944), reaching their high point with the Treaty of Rome in March 1957, which inaugurates the European Economic Commission (EEC), made up of the three-country members of Benelux plus France, Italy and Western Germany. This first batch of regional initiatives lasted up to the mid-1970s and was especially successful in Europe, with the EEC and a customs union between the Scandinavian countries - Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland - in 1948 (which was later dismantled as these countries joined the European Free Trade Accord). Other attempts outside of Europe did not meet similar success, like the Latin American Free Trade Agreement (LAFTA), created in 1960. Reasons for the LAFTA’s failure include the institution of import substitution policies (Carranza 2017), incompatible with commercial liberalization on both inner- and outer-bloc trade; and the emergence of smaller blocs within Latin America in the 1960s, like the Central American Common Market (1960) and the Andean Pact (1969). The second wave occurs during the 1990s and is marked by open regional deals, in which preferential trade areas are accompanied by multilateral steps toward commercial liberalization. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is created at this point, and the US’s adherence to regional deals is also a defining trait of this wave. According to Ethier (1998), other characteristics include geographical proximity, which underlies deals; the policy breadth of such deals often goes beyond tariff reduction; and the persistent asymmetry between countries: deals are frequently held between large and small economies.

New Regionalism shaped the plurilateral trade deals (those between three or more countries) that saw a boost in the last thirty years. To examine this form of commercial integration and how it compares and relates to multilateralism, Bhagwati and Panagariya (1996) asked whether the two are friends (complementary) or foes (substitutive). Regionalism dictates a preferential tariff advantage for member countries, violating multilateralism’s main principle, the MFN. This provides an argument for viewing the two scopes of integration as “foes,” since at any level of regional integration (from a free trade area to an economic union), intra-bloc trade is given priority over multilateralism through lower-than-MFN tariffs, essentially creating a discriminatory system based on the origin of goods. The stagnation of the WTO’s current multilateral Round (Doha) has pushed countries to seek region-based environments of commercial liberalization. Furthermore, tax deduction in developed countries has been negligible (Crivelli 2016), creating trade and development opportunities for emerging countries by means of regional deals.

On the other hand, advances in institutional structuring like the spread of democracy and geopolitical stability, as well as the “domino effect” caused by the growing number of preferential trade deals (Baldwin 1993), make a case for the “friends” view. Liu and Ornelas (2014) argue that political stability is a necessary condition for commercial liberalization on a regional level. Baldwin (1993) postulates that the opportunity cost for not engaging in preferential trade deals is high, given that most countries are becoming members of such agreements and, by that strategy, gain competitiveness. It is also fair to assess that the advances in multilateralism lay the groundwork for regional blocs by creating incentive mechanisms.

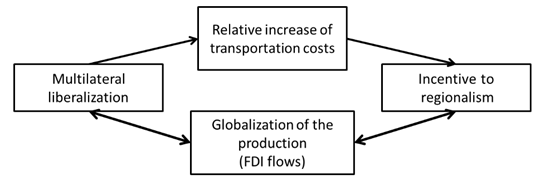

Source: Prepared by the authors (2018).

Figure 1. The Complementary Relation between Multilateralism and Regionalism

As per figure 1, multilateral liberalization lessens the importance of tariff cost for commercialized goods as an initial channel of influence. In other words, transportation cost has higher participation in international trade. This results in an incentive to trade between close countries, given commerce gravitation. Given the WTO’s status as a trade facilitator and provider of a business-friendly environment, geographically close countries are incentivized to form regional blocs. The second channel of influence pertains to distinct yet simultaneous phenomena (as opposed to a causal link between them); from this, especially during the 1990s, multilateral rounds succeed alongside the formation of new regional deals (Ethier 1998). This complementary link is fomented by the liberalization of international investment flows, expressed as intra-industry and intra-bloc international trade. Therefore, multilateral liberalization reinforces the expansion of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows, which take advantage of tariff preferences and the extended regional market (Saggi 2002).

The arguments presented above apply to the particular case of two-country regionalism, i.e., bilateralism. However, this is a recent phenomenon, jumping from 54 deals of such nature in 2001 to 217 in 2018. Bilateral deals are characteristically asymmetric, where many deals have one country with a considerably larger economy than the other - this leads to a commercial system with multiple bilateral tariffs, known as a “spaghetti bowl” (Baldwin 2006). The spread of bilateralism benefits from the institutional apparatus provided by multilateral organizations and owes itself to multilateralism’s failure to advance in contemporary trade rounds.

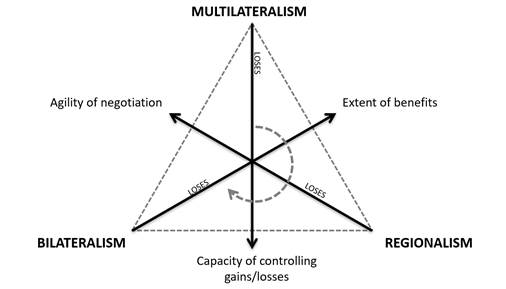

Source: Prepared by the authors (2018).

Figure 2. Multilateralism, Regionalism and Bilateralism Dilemma

Figure 2 describes the advantages and losses taken by choosing one form of commercial integration over the others. The dashed arrow in the center points clockwise to indicate a historical analysis, starting from multilateralism, going through regionalism, and finally bilateralism. In each case, there are two advantages and one loss. Multilateralism benefits from the WTO’s institutional infrastructure, resulting in a transparent, trustworthy, and democratic - and thus, diligent - business system for all 164 members. The WTO’s norms and procedures provide a secure foundation for efficient concession negotiations, as exemplified by the Dispute Settlement Understanding. Notice, however, that the agility of negotiations assumed under multilateral deals is especially valid in comparison to the case of large regional agreements, which usually lack information, legal support, and regulation infrastructure. The other privilege of this trade cooperation form pertains to the sheer scope of advantages it offers since a universal, multilateral structure allows for higher reaching specialization gains. The loss comes from the short-term local socioeconomic adjustment cost, and the subsequent inability countries have to react to such losses.

The case for regionalism is comparable, as these deals share the ability to adapt negotiations to their local needs. Furthermore, regional initiatives retain the width of advantages proportional to the number of members of the particular deal. However, what sets it apart from multilateralism and bilateralism is that regionalism lacks both the extensive institutional apparatus the former provides (losing agility) and the natural ease of business inherent to the latter. Experience shows that regional rules and procedures infrastructure is incipient, leading to high transaction and business costs at this level of integration.

Finally, bilateralism boasts a self-evident edge that flows naturally from a direct and efficient deal between two players. With it comes a greater possibility for maintenance, evaluation, and control over gains and losses for both parties involved. Bilateralism loses in how its commercial liberalization is limited to the specialization opportunity between both countries.

Protagonists of Bilateralism

Bilateralism can be viewed as a natural commercial deal where two countries with cultural or geographic proximity share transaction costs lower than those incurred by regional or multilateral deals. The adhesion to bilateralism has been significantly influenced by the early conversion of the world’s two largest economic powers. First, the US signed a bilateral FTA with Israel in 1985, followed by a regional FTA with Mexico and Canada in 1992. Second, China showed interest in bilateral agreements since its membership in the WTO, given the FTAs established with its internal regions, Macau and Hong Kong, in 2003.

Each country has followed a specific modus operandi in negotiating and implementing bilateral trade deals. On the one hand, the US policy towards trade agreements can be described as a strategy marked by a standardized posture regarding goods coverage and tariff exemptions. On the other hand, the rapid rise of China’s FTAs denotes the country’s propensity to bilateralism, which is dominated by an idiosyncratic give-and-take profile.

Source: Prepared by the authors (2019). Raw data: WTO (2018).

Figure 3. Number of Bilateral FTAs of the USA, China, and the World (2001-2018)

Even though the US has a longer history with FTAs than China, both countries show a sharp increase in bilateral trade engagement from the early 2000s onwards (figure 3). The combined share of China and the US in world bilateral FTAs increased from 5.5% in 2001 to 13.4% in 2018. These numbers come primarily from China, which has experienced a higher bilateral FTA growth rate than the US in this timeframe. Bilateral FTAs have also become a popular strategy among other nations. As shown in figure 3, bilateral FTAs not containing China and the US increased from 51 deals in 2001 to 188 in 2018. Japan is another country that has experienced a surge in bilateral agreements (from 0 in 2001 to 16 in 2018).

Table 1a. China´s FTAs: Partner Countries, Trade Scope and Gravity Variables

| China FTAs | Goods (HS-2) | S/I | Distance | GDP (Millions USD) |

| Macau (2003) | 17, 19-22, 25, 29- 30, 32-33, 35, 38-39, 42, 48, 52, 54-55, 58, 60-65, 70-71, 73-74, 84-85, 90-92, 94-96. | S/I | 1989 | 50,361 |

| Hong Kong (2003) | 21, 27-28, 30, 32-33, 35, 38-39, 41, 48-55, 58-64, 70-71, 73-74, 76, 80, 83-85, 90-91, 95-96. | S/I | 1973 | 341,449 |

| ASEAN (2004) | 01-97 | S/I | 1,749,503 | |

| Brunei | 3900 | 12,128 | ||

| Cambodia | 3349 | 22,158 | ||

| Indonesia | 5220 | 1,015,539 | ||

| Laos | 2778 | 16,853 | ||

| Malaysia | 4348 | 314,71 | ||

| Myanmar | 2957 | 67,069 | ||

| Philippines | 2854 | 313,595 | ||

| Singapore | 4480 | 323,907 | ||

| Thailand | 3298 | 455,303 | ||

| Vietnam | 2327 | 223,78 | ||

| Chile (2005) | 01-97 | S | 19086 | 277,076 |

| Pakistan (2006) | 01-23,25-61, 63-66, 68-76, 78-92, 94-97 | S/I | 3886 | 304,952 |

| New Zealand (2008) | 01-97 | S/I | 10793 | 205,853 |

| Singapore (2008) | 09, 11-23; 27-30; 32-35; 37-45; 48, 51-74, 76, 82-87, 89-97 | S/I | 4483 | 323,907 |

| Peru (2009) | 01-97 | S/I | 16667 | 211,389 |

| Costa Rica (2010) | 01-97 | S | 14100 | 57,286 |

| Iceland (2013) | 01-97 | S/I | 7891 | 23,909 |

| Switzerland (2013) | 01-97 | S/I | 7990 | 678,887 |

| South Korea (2015) | 01-97 | S/I | 954 | 1,530,751 |

| Australia (2015) | 01-97 | S/I | 9019 | 1,323,421 |

| Georgia (2017) | 01-97 | S | 5851 | 15,081 |

| Maldives (2017) | n/a | n/a | 5857 | 4,866 |

Source: Prepared by the authors. Raw Data: (MOFCOM 2020).

The US and China hold nearly the same number of bilateral FTAs (23 and 19, respectively), but some discrepancies are worth mentioning. As pointed out above, there are gaps in some Chinese FTA deals - that is, while many agreements offer full coverage, some exhibit tariff lines that are not below the MFN level. It is worth noting that for four out of its 15 trade agreements (Macao, Hong Kong, Pakistan, and Singapore), the scope for a preferential tariff is lower than full coverage. As for the US, the preferential tariff (usually zero) applies for all goods and all agreements, indicating a homogeneous trade treatment to its FTA partners.

Table 1b. The US FTAs: Partner Countries, Trade Scope, and Gravity Variables

| USA FTAs | Goods | S/I | Distance | GDP (Billions USD) |

| HS-2 | ||||

| Israel (1985) | S | 9495 | 351 | |

| NAFTA (1992) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | ||

| Mexico | 3032 | 1,150,888 | ||

| Canada | 734 | 1,653,043 | ||

| Jordan (2000) | 1-76; 78-98 | S | 9535 | 40 |

| Singapore (2003) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | 15546 | 324 |

| Chile (2003) | 01-76, 78-98 | S/I | 8070 | 277 |

| Australia (2004) | 01-76, 78-98 | S/I | 15945 | 1,323 |

| Morocco (2004) | 01-76; 78-98 | S/I | 6144 | 110 |

| CAFTA (2004) | 01-76, 78-98 | S/I | ||

| Costa Rica | 3298 | 57 | ||

| El Salvador | 3046 | 25 | ||

| Guatemala | 3003 | 76 | ||

| Honduras | 2932 | 23 | ||

| Nicaragua | 3112 | 14 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 2372 | 76 | ||

| Bahrain (2005) | 01-76, 78-98 | S | 10957 | 35 |

| Oman (2006) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | 10580 | 73 |

| Peru (2006) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | 5665 | 211 |

| Colombia (2006) | 01-76, 78-98 | S/I | 3824 | 314,458 |

| Panama (2007) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | 3337 | 62 |

| Korea (2007) | 1-76; 78-98 | S/I | 11165 | 1,530,751 |

Source: Prepared by the authors. Raw Data: USTR (2020).

Previous literature has emphasized the role of geopolitical issues as an underlying factor in the Chinese trade policy. Gabuev (2016) argues, for instance, that the expansion of Chinese FTAs to Southern and Central Asia and its One Belt One Road initiative demonstrates the country’s priority in consolidating its position as a regional power in Asia. Similarly, Garcia-Duran, Kienzle, and Millet (2014) argue that China’s FTAs in the Pacific Rim region are politically motivated agreements that aim to reward diplomatic allies and balance the US influence in the area. More specifically, a comparative analysis relying on the gravity approach shows that the average US FTA partner is farther away than the Chinese one (8.2 thousand kilometers for the US and 7.6 for China). As for their size, China’s partners usually include larger economies, with an average GDP of US$ 209 billion, against an average of US$ 73 for US partners. These results indicate that the implications for Chinese trade policy are twofold. First, China shows a much more pronounced regional bias in its choice of FTA partners than the US since they are based globally. Second, that the experience acquired by the country in its first agreements later enabled Chinese trade authorities to efficiently negotiate trade deals with larger economies like South Korea and Australia. This comes despite China’s earlier preference for FTAs with small economy countries - which is consistent, for instance, with Salidjanova (2015).

Indeed, the first wave of FTA agreements signed by China and the US reveals that both countries focused on trade partners that are either small economies or geographically near countries. Israel and Jordan are examples of this US experience, and they also bring forward the prevalence of political issues in these first agreements. Besides, it is worth stressing the US initiative in forming its first and only regional FTA with Mexico and Canada. Although NAFTA signaled a breaking point for the US trade policy regarding its favorable position concerning multilateralism, it acknowledges - along with all other bilateral FTAs in the first decade of the 2000s - a complementary perspective between multilateralism and bilateralism. Conversely, the Chinese experience shows an initial preference for bilateral FTAs at a regional level to consolidate its hegemonic position in Southeast Asia, as exemplified by the ASEAN (Ba 2003). Furthermore, the increasing number of bilateral FTAs in the early 2000s can be interpreted as a strategy to balance tariff concessions in the context of MFN trade. This strategy is twofold: given China’s limited negotiation power in a multilateral context, the WTO environment poses a “slowest boat” strategy, according to Hoadley and Yang (2007); additionally, Li, Wang, and Whalley (2014) posit that China implicitly demands a favorable posture of its potential and effectual FTA partners with respect to market-economy status recognition within the WTO.

Beyond trade motivation, FTAs can also be driven by the prospect of freer capital markets. Given that those investment treaties are, in general, highly specialized - dealing with different types of concessions by sectors rules to transfer capital technology and profits, and its own dispute resolution mechanism - they tend to be originally celebrated at a bilateral level. The experience of both China and the US ratifies the fact that investment treaties come before trade deals. Indeed, all FTAs signed by either country were Bilateral Investment Treaties already in effect. Table 1 shows that all FTAs in China or the US predominantly encompass investment issues in a specific chapter of the trade deal, which either extends or ratifies regulation privileges established by previous bilateral treaties. Although the prominent evidence is the same for the US case, there are three exemptions where FTA coverage is limited to goods and services only.

Table 2. China and the US FTAs: Share of Partner Countries (2010 and 2017)

| China | USA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partner | % 2010 | % 2017 | Partner | % 2010 | % 2017 |

| Hong Kong | 7.75% | 9.64% | Israel | 1.00% | 0.88% |

| Macau | 0.08% | 0.11% | NAFTA | 28.51% | 29.06% |

| Asean | 9.85% | 17.33% | Mexico | 12.20% | 14.18% |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.03% | 0.03% | Canada | 16.32% | 14.88% |

| Cambodia | 0.05% | 0.19% | Jordan | 0.07% | 0.09% |

| Indonesia | 1.44% | 2.13% | Chile | 0.57% | 0.63% |

| Lao People’s Dem. Rep. | 0.04% | 0.10% | Singapore | 1.44% | 1.25% |

| Malaysia | 2.50% | 3.23% | Peru | 0.38% | 0.41% |

| Myanmar | 0.15% | 0.45% | Bahrain | 0.05% | 0.05% |

| Philippines | 0.93% | 1.73% | CAFTA | 1.51% | 1.40% |

| Singapore | 1.92% | 2.67% | Costa Rica | 0.43% | 0.28% |

| Thailand | 1.78% | 2.69% | El Salvador | 0.14% | 0.14% |

| Vietnam | 1.01% | 4.10% | Guatemala | 0.25% | 0.29% |

| Chile | 0.87% | 1.20% | Honduras | 0.27% | 0.25% |

| Pakistan | 0.29% | 0.68% | Nicaragua | 0.09% | 0.12% |

| New Zealand | 0.22% | 0.49% | Dominican Rep. | 0.32% | 0.32% |

| Peru | 0.33% | 0.68% | Morocco | 0.08% | 0.09% |

| Costa Rica | 0.13% | 0.08% | Australia | 0.94% | 0.88% |

| Iceland | 0.00% | 0.01% | Panama | 0.20% | 0.17% |

| Switzerland | 0.68% | 1.22% | Oman | 0.06% | 0.08% |

| Australia | 2.97% | 4.59% | Colombia | 0.87% | 0.69% |

| Rep. of Korea | 6.96% | 9.42% | Rep. of Korea | 2.75% | 3.08% |

| Georgia | 0.01% | 0.03% | Partners | 38.45% | 38.77% |

| Maldives | 0.00% | 0.01% | World | 100% | 100% |

| Partners | 19.52% | 45.48% | |||

| World | 100% | 100% | |||

Source: Prepared by the authors. Raw Data: UN Comtrade (2019).

As for preferential partner relevance in total trade, the share of China’s FTA partners is not only currently higher than that of the US (45.5% against 38.8%), but it also shows a higher increase over the last seven years. Even though the number of partner countries with preferential trade is about the same for both countries, the individual agreement that yields the largest share in total trade in the US corresponds to 75% of its total FTA trade (NAFTA), while ASEAN (China’s most significant agreement) accounts for only 38.1% of its total trade. This result indicates that the US policy towards FTA deals may be reasoned by other aspects than trade interests. China’s trade relies more evenly on distinct FTA partners partly because some FTA agreements are recent - such as Korea and Australia (signed in 2015). These large shares of trade with FTA partners follow distinct patterns for both countries: China stands not only as a latecomer on bilateral trade deals but also has recently targeted larger economies such as South Korea and Australia (representing jointly around 14% of Chinese foreign trade). Despite China’s position as a leading trade partner of many Latin American countries (Perrotti 2015), the number of partners of this region in China’s FTAs is low (exceptions are Chile and Costa Rica) since they are constrained to negotiate trade deals outside their current agreements (e.g., Mercosur and Andean Community).

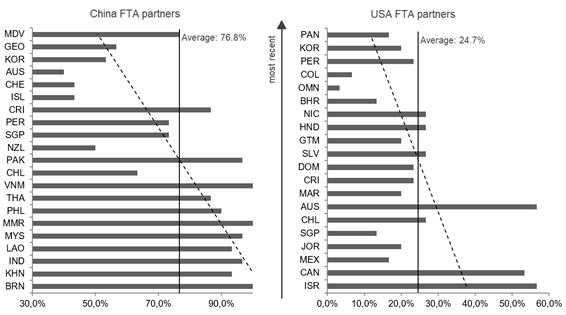

FTAs can have motivations that go beyond commercial and economic interests. To capture their political similarities, we account for a degree of political convergence by computing the number of common votes between either China or the US and each of their respective FTA partners along the 30 latest resolutions voting procedures at the UN General Assembly. We assume a high relationship between voting coincidence and the existence of an FTA between the two countries and disregard the causal link. The voting behavior of UN member states has also been argued to capture the degree of political alliance. Dreher, Nunnenkamp, and Thiele (2008) argue that the number of coincident votes is a measure of how foreign aid is used to influence the recipients’ voting behavior in the UN General Assembly.

Figure 4 depicts the percentage of coincidental votes between either country and their FTA partners, indicating that the average political proximity plays a more significant role in FTA partner choice for China than for the US (76.8% coincident voting for China and 24.7% for the US). This result indicates that China shows a higher commitment to forming FTAs with political allies. It is worth noting that both countries started off deciding to form FTAs with politically allied partners.

Source: Prepared by the authors. Raw Data: United Nations Digital Library (2019).

Figure 4. Percentage of Common UN Voting Strategy between China and the US and their Respective FTA Partners

The prospect of a trade agreement involving one of the two largest economies in the world comprises two dimensions. The first refers to the limited potential growth of bilateral agreements that each country can celebrate since many key partners are constrained by being part of customs unions (e.g., Mercosur and European Union) and therefore should pursue either an FTA with all countries in the CU or no trade agreement at all. The second dimension regards a new format of trade deals that not only overcomes the reduced economic gains of bilateralism but also enlarges the number of member countries and the geographic reach of the agreement. The so-called mega-trade deals may move trade concentration toward a few large trading blocs. Since US President Trump withdrew the US signature from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, the perspective for the country to engage in a mega-trade agreement remains with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), which can be regarded as a large bilateral deal (between the US and the European Union). As for China, the mega-trade deal at stake is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Although neither partnership is in effect - they face a significant loss of momentum due to the trade war between China and the US - the role of these two large countries in these intercontinental trade agreements is based on a first-move and reaction behavior. As Ye (2015) points out, RCEP is an expansion of ASEAN to embrace economies as diverse as China, Malaysia, Australia, and Japan; and, also, from the Chinese perspective, it lies as a strategy to pave the way for the new Silk Road. A decision of China or the US to move forward with these mega-trade arrangements may induce the other - as a sort of domino effect - also to follow the same strategy.

Conclusion

This study sought to evaluate the expansion of bilateralism and its place in the international trade regimes. From a conceptual standpoint, we can argue that the traditional multilateralism-regionalism dichotomy does not accurately describe the reality of trade regimes in the past two decades. Therefore, we described how the rapid rise of bilateral deals presents a new trade policy paradigm. We identified the distinctions and similarities between regionalism, bilateralism, and multilateralism and provided evidence on the main characteristics of the US and China`s experience of bilateral trade deals.

Bilateralism and regionalism are similar in that they present alternatives to multilateral trade liberalization and, therefore, are a means to regain agency to measure and negotiate profits and losses in trade deals. Regional blocs can be constrained and fostered by countries’ geographical proximity and present them with a wider array of benefits prompted by productive specialization. On the other hand, bilateral deals allow for a tailored agreement with discretionary measures pertinent to the countries’ needs.

Bilateral agreements also serve a diverse menu when it comes to options in partners and the scope of goods or services included in the concessions. These choices, however, are determined by the degree of asymmetry between players. When considering the two largest world economies, empirical data shows a sudden increase in bilateral FTA participation by China and the US in recent years. While other countries - such as Japan and the EU members - also show a high number of bilateral agreements, the US and China markedly seek out asymmetric deal opportunities, prioritizing smaller economy partners.

The comparison between the Chinese and the US experience in trade agreements outlines one main similarity (the number of deals in effect) and a few disparities. We found out that there are four striking features concerning these differences. First, bilateral FTAs signed by China initially showed a clear inclination for an idiosyncratic goods and services coverage policy (regarding tariff perforations), while the US followed a standard procedure strategy of full coverage since the beginning. Second, China has shown a preference for making trade deals with neighboring countries - measured by a shorter average distance between China and its partners - which ratifies the concept that China seeks regional hegemony. Third, there are discrepancies regarding the diversity of partner countries: China’s preferential trade relies more evenly on its trade partners while NAFTA’s intra-regional trade heavily dominates trade flows among the US’s FTA partners. Fourth, as a non-economic insight, underlying the decision process of FTA-making, our hypothesis of political proximity - accounted by a similar UN voting strategy - has proven to be more prominent in Chinese trade authorities’ initiatives than in the US.

In sum, the US trade policy in bilateral FTAs exhibits a negotiation menu that is less customized with respect to an idiosyncratic posture adopted by China. Further, US choices regarding FTA partners stressed a lower degree of political and geographical bias than Chinese preferences. Therefore, the US trade policy reveals a more pragmatic and standard behavior towards bilateral trade agreements.