Introduction

Corruption is one of the most prominent problems in Latin America as of today. The Odebrecht and the Panama Papers scandals that have swept the region since 2016 showed a part of the complex “social life” of corruption in Latin America (Goldstein and Drybread 2018). However, the attention given to grand corruption must not make us ignore petty corruption and its role in citizens’ daily life. Neither should we ignore the psychological mechanisms that make countries fall into a “corruption trap” where corruption is normalized (Klašnja et al. 2018). That is precisely our aim: to put upfront the study of petty corruption and its relation to the concept of social desirability. We seek to explore how social desirability bias (SDB) affects reports about past bribing behavior among different groups of citizens. Could SDB be affecting the results obtained through direct questions about bribing behavior such as the one used by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), the World Values Survey (WVS), Latinobarómetro, and other regional surveys? Overall, what drives citizens into admitting having committed an act of corruption? Do some citizens feel ashamed to report that they have engaged in bribing behavior when asked directly despite corruption being widespread? These questions are important both by themselves and because they make us rethink previous findings about the incidence of corrupt behavior.

We contend that a psychological approach to the study of corruption can be fruitfully employed to understand who lies about corrupt behavior and why. At its core, corruption is a question of morality, understood in a thick sense as quandary ethics (Durkheim 1925), where the main question is what is the right thing to do. And, thus, it can be approached from a moral psychology perspective: by exploring when and why people conceal their engagement in corruption we are falling into the domain of moral cognition, which is the “reflection of the social appropriateness of people’s actions” (Bzdok et al. 2012, 789). Furthermore, since SDB is related to the appropriateness of behavior, the existence of conflicting social norms in a context where corruption is rampant-like in several Latin American countries-can result in SDB in the context of surveys and in variation in SDB among different subgroups.

Moral psychology focuses on how individuals resolve quandaries (Haidt and Kesebir 2010) and offers two complementary explanations for this. On the one hand, it is possible that the social norms that lead to an individual engaging in corruption are different or operate differently than the ones that lead to admitting or concealing this engagement. Importantly, these norms may be different or behave differently across subgroups of the population. On the other hand, it is also possible that in a context of high corruption some individuals become unable to perceive their actions as instances of corruption, even though they have internalized the moral norm that would condemn such behaviors (Feldman 2018). Thus, different exposure to levels of corruption across social groups and variant expectations about appropriate behavior among social referents might explain different attitudes and behaviors within society.

To address these questions, we focus on Peru, a case with widespread corruption within the region. According to LAPOP, in 2016-2017 Peru ranked the highest in the region in terms of corruption, which was considered the country’s main problem. Moreover, since 2016-2017, perceptions of corruption have increased in Peru. At the same time, bribing behavior is above the regional average (Carrión et al. 2018; Zechmeister et al. 2017). This makes Peru an interesting case to explore the workings of SDB and corruption: even though it is considered a problematic aspect of politics, it is also a common and widespread behavior amongst citizens. Therefore, Peru represents a contrasting case to explore this puzzle, since previous literature on the subject has focused on cases such as Costa Rica (Oliveros and Gingerich 2019), in which perceptions of corruption are comparatively low and bribery is an uncommon behavior.

To understand how SDB affects reports about past bribing behavior among different groups of citizens in Peru, we follow a mixed methods strategy. We begin with the analysis of six focus groups conducted to gain in-depth information about how Peruvians think about bribing and its acceptability to solve daily problems. This allows us to assess how social desirability works in a context where corruption is widespread. Subsequently, we estimate the degree of SDB through an original list experiment (LE) and analyze these results, comparing them with responses to an equivalent direct question about bribing behavior included in the same survey.

This methodological strategy is a contribution in and of itself. In most of the political science literature on SDB, list experiments and other unobtrusive survey techniques are the sole methods used. This is striking considering that focus groups are more likely to elicit useful feedback on sensitive topics (Madriz 1998; Cyr 2019). Likewise, this method allows the researcher to grasp the mental processes underlying a preference or judgment (Bratton and Liatto-Katundu 1994) and generate information related not just to individuals, but also to the group interactions (Kidd and Parshall 2000). Indeed, few studies to this date inform survey experimental results on corruption perceptions with original focus group analyses (Pavão 2018).1

Both focus groups and survey results provide substantial leverage to our psychological approach. Overall, we confirm that SDB is at work even in a context in which corruption is rampant. The LE estimate of respondents who engaged in bribery is higher than the proportion obtained when asked directly. The statistical analysis of these results reveals that gender plays an important role in SDB when it comes to reporting corruption: men tend to overreport the extent of their bribing behavior when asked directly compared to when asked anonymously through the LE. We do not find any significant differences based on socioeconomic status (SES) and age, and this on itself is interesting, since other studies have found these factors to be possible sources of SDB. These results underscore the importance of designing unobtrusive measures when studying the prevalence of corrupt practices in Latin American societies like Peru. Furthermore, by exploring the role that SDB plays for different groups in the population, this study emphasizes the need for a more thorough understanding of the factors that affect the willingness to admit to having participated in corrupt behavior.

Theoretical Discussion and Argument

We are concerned with understanding what drives citizens into admitting having committed an act of corruption in contexts where corruption is widespread. It is well documented how sometimes people lie when asked about normatively charged behaviors, given the pressure of face-to-face surveying or concerns about anonymity (Bradburn et al. 1978; DeMaio 1984). Since corruption is socially reprehensible in most societies, asking directly about participation in corrupt acts could generate biased estimates about its incidence (Gingerich et al. 2015; Oliveros and Gingerich 2020; Gueorguiev and Malesky 2012; Pavão 2015). In particular, the desire to avoid embarrassment and to project a favorable image to others could lead respondents to overreport the socially desirable behavior (Fisher 1993).

But not all individuals hide their truthful answers when asked about their bribing behavior upfront. What makes some individuals more likely to lie about petty corrupt behavior? Existing studies of SDB in the face of corruption-related survey questions in Latin America have pointed to one important empirical finding: SDB is likely to be associated with concern about social class status (Kiewiet de Jonge 2015; Oliveros and Gingerich 2020). However, the direction of this association is not clear. While in Costa Rica the less educated were more inclined to lie about corruption (Oliveros and Gingerich 2020), the more educated across eight Latin American countries turned out to be more likely to lie about receiving gifts during electoral campaigns (Kiewiet de Jonge 2015). Moreover, these studies are not conclusive about other individual characteristics, such as gender, either.

While these behavioral findings point out important directions, they do not explain why individuals lie about socially sanctioned behavior. More specifically, we still do not understand why some individuals are more likely to lie than others under some situations. We contend that a psychological approach can help fill this void. As mentioned previously, corruption behavior and the report of this behavior is innately related to quandary ethics or to the question of what one should do or say to have done. Moral psychology focuses on how individuals resolve these quandaries (Haidt and Kesebir 2010). Instead of taking a normative view of morality with a focus on the content of morality, recent moral psychology approaches have taken a more descriptive approach to morality, focusing on moral systems that are “interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, technologies, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperative social life possible” (Haidt 2008, 66).

In these moral systems, beliefs about how others act in society are an important piece of information that individuals take into consideration to form their attitudes and make behavioral decisions. Corruption may corrupt because both the decision to engage in corruption and to lie about it may be heavily dependent on how we expect others to behave, or how we believe others expect us to behave in each context (Andvig and Moene 1990; Bicchieri 2006; Ganegoda and Bicchieri 2017; Karklins 2005). Regardless of the legal framework, moral and social anti-corruption norms may also exist. In contexts where corruption is low, anti-corruption norms have likely been internalized as moral norms by most individuals. Moral norms are “practice independent” and followed regardless of the majority’s view (Brennan et al. 2013, 72). When universalistic norms such as equality before the law are internalized, individuals are less likely to engage in bribery. But even when anti-corruption norms are internalized, some individuals might fall into corrupt behavior without even being able to realize it when doing so,2 falling into “moral blindness.”

When corruption is widespread, anti-corruption norms might not be internalized as moral norms but merely be present as one of the multiple social norms that may or not influence behavior.3 In contrast to moral norms, “social norms are shared understandings about actions that are obligatory, permitted, or forbidden” (Ostrom 2000, 143-144) and depend on external enforcement through sanctions (Elster 2011). This conflict among different types of norms can lead to the disregarding of formal norms or social norms that condemn corruption in favor of others that, for instance, may justify the act based on helping kinfolks in need (Dungan et al. 2014). Even if corrupt practices may be seen as acceptable problem-solving strategies (Darley 2005; Ferreira et al. 2012; Huber 2008), or even unavoidable (Pavão 2016), engaging in a corrupt act may still generate stress or discomfort in individuals who acknowledge that other existing social and moral norms condemn it.4 Thus, individuals could decide to lie about past bribing behavior because it is expected of them to behave according to a different set of norms.

Considering this plausible conflict among norms, our psychological framework would expect to find some degree of overall SDB when asking about past corrupt behavior even in contexts where corruption is rampant (H1), such as Peru. When prompted to talk about bribing in focus groups, people prone to lying might discount their amoral behavior altogether or experience some degree of discomfort that leads them to justify their past actions. An alternative rational choice approach would expect neither blindness towards one’s amoral behavior nor discomfort-prompted justifications, but instead would expect rationalizations that point to some sort of cost-benefit assessment.

Moreover, varying expectations about appropriate behavior among social referents might explain different propensities of lying about past bribing behavior. Since normative expectations are typically formed based on a reference group, the desire to avoid embarrassment and project a favorable image to others (expressed in SDB) may operate differently according to socialization processes and concerns for social standing associated with one’s situation.

In summary, it is important to acknowledge that social stigma can be associated with bribing even in contexts where corruption flourishes, thus leading to the emergence of SDB during survey interviews. Nonetheless, rejection of corruption is plausibly one of several competing social norms; it can be reframed or re-signified under specific circumstances allowing individuals to circumvent the moral sanction associated with it. Normative and empirical expectations about corrupt behavior, informed by referent groups, may make a difference. Thus, to further specify testable expectations about possible group sources of SDB, we should first delve into the Peruvian context, by discussing the discussions held in the focus groups conducted.

“Bribery is what we see every day”5

Since beliefs about how one should act are context dependent, we must start by identifying what Peruvians associate with “corruption,” how they evaluate it and why. To do so, we take advantage of six focus group sessions conducted in the city of Lima between June 12 - 22, 2017. Each of them consisted of eight participants and a moderator, making it a total of 48 participants. Groups were composed of an equal number of males and females, and participants were recruited according to two control variables: SES (three categories corresponding to low, medium, and high SES) and age (two cohorts: 25 years or younger and 26 years or above).6

While discussing what corruption is, participants were inclined to associate this practice with “bad” behaviors. Adjectives that were repeated were “wrong,” “illicit,” “amoral,” “double moral.” Participants also condemned corruption since they saw it as a practice associated with “selfishness” or “convenience.” Indeed, for many people, all the “wrongs” seemed to go together; thus, the limit between corruption and other common offenses, such as theft or scam, did not always appear clear. The image of corruption appears also blurred in the sense that any type of abuse of power by public officials or companies (entities with power) was perceived as corruption. Moreover, when asked about the necessary ingredients that create corruption, it was clear for all that there is always some kind of transgression of norms involved. So, for corruption to exist we need first, “bad people,” “criminals,” “selfish” or “lack of awareness.” All these terms indicate that corruption is morally condemned in Peru.

Second, all participants agreed that corrupt situations need some type of authority: someone with power of decision, who can change norms or ignore their enforcement. Although most discussions typically referred to public officials, all groups concluded that corruption is not limited to the public sector since one can have authorities who abuse their power in the private sector too. A common example given referred to situations in private educational institutions where corrupt teachers or directors ask for bribes. Furthermore, although there was not a complete agreement on this, many view money (or any other tangible good) as a necessary component of corrupt transactions, an element that would help distinguish corruption from other “bad” behaviors. Furthermore, money helps distinguish bribing from less socially stigmatized and prevalent social practices such as undue influence.

Additionally, the visual stimuli shown encouraged participation and the sharing of experiences. We learned, first, that bribing is one of the main situations that come to mind when participants are prompted to think about scenarios that involve a (possibly) police officer thanking someone after receiving an envelope. Around 39% of the interventions (across focus groups) described that they saw a bribing scene involving a police officer and a citizen. When discussing the plausibility of the scene, participants also mentioned that policemen are perceived to be more corrupt than their female peers, which coincides with previous findings about preconceived ideas about female security forces (Karim 2011; Flores-Macías and Zarkin 2021). On the other hand, 6% of the interventions characterized the interaction using a euphemism such as “gratitude,” “favor,” and “fixing up.” Other situations identified included having a citizen asking a police officer about an address, a police officer giving back some lost documents to a citizen, and other exchanges of personal nature, such as the payment of a personal debt.

These discussions also confirmed that bribing is a morally charged behavior, expected to be publicly condemned. Before describing what they saw in the picture, each participant wrote (anonymously) a title for it. When contrasting the collective debates and individual written responses, we noticed that the use of euphemisms decreased in public interventions to more than half (6%) to what was used in written notes (15%). Moreover, during group interactions, a slightly higher proportion of participants (39%) identified the picture as representing a bribing scene than they did so on paper (35%). This could indicate that collective discussion with peers makes some people change their mind and identify a situation that is known to be morally condemned at large in Peruvian society as bribery.

Bribes involving police officials are, according to participants, extremely common in Peru. The mean frequency score assigned collectively across focus groups is 8.8 (out of 10). When asked to list typical situations in which a police officer may be offered or could ask for a bribe, two main categories emerged very early in the discussion across all groups: bribes for expediting procedures and bribes for avoiding traffic infractions. For most participants, these constitute the core of everyday interactions with police authorities. One interesting difference to highlight is that more men than women admitted having participated in corrupt exchanges with police officers, and more than half of the women who admitted being part of a bribing encounter mentioned that they were not the protagonists of these exchanges, since these were led by men accompanying them. Additionally, participants identified that paying a bribe to release someone from prison was also a common situation. Other types of bribing encounters were closer to experiences of specific groups, such as buying food for a prisoner (lower SES) or to pressure someone (higher SES).

The widespread nature of corruption in everyday interactions is even more evident when participants are asked about their experiences with bribery beyond interactions with the police. Some of the most common situations reported involve educational institutions, municipalities, and health centers. Although initially participants discussed their indirect experiences with corruption, they later began to reveal instances in which they had paid bribes. Interestingly, participants from lower SES considered bribery more acceptable than participants from middle and high SES. This is particularly noticeable when contrasting discussions from young respondents from high and low SES.

In addition, we find some evidence that shows that corruption might be associated with social status in Peru. When participants were asked to describe the embodiment of a typical corrupt businessperson and politician, all participants agreed that it would be a man from high or middle to high SES. During these discussions, we also identified some negative stereotypes associated with lower SES citizens. For instance, we detected some condescending comments about bribery being connected with “ignorant” people that “lack education or knowledge,” who bribe authorities instead of demanding respect for their rights. On the other hand, participants also mentioned the idea that lower SES people would be less able to engage in grand corruption. One participant from low SES commented that “an ignorant” will never become a corrupt official; the subtext being that you need to be a resourceful person. This resonated with a conversation held by high SES young participants who made clear that to participate in corruption you must “play your cards,” “you have to know, you have to be feared, you have to move, you have to be friendly, reliable.”

Despite some differences in perceptions between SES subgroups, there was a general agreement about the unacceptability of paying bribes to avoid a traffic fine. In contrast, participants found it more acceptable to bribe for expediting procedures.7 In terms of gender, it is important to highlight that it was the male participants who led the discussion about different levels of acceptability of corrupt situations, and mostly emphasized the relativeness of the acceptability of these actions. For the most part, men mentioned the need to relativize the judgment depending on the seriousness of the offense/crime committed. In their interventions, some women presented instead a less nuanced position, stating that the use of bribery is generally unacceptable.

Two types of rationale emerged to justify these collective evaluations. The first one-more prevalent-consists of a rationalization of the negative externalities of bribing: situations considered less acceptable are the ones that result in harm to others. The following exchange among young participants from low SES is illustrative of this point:

Bribing when drugs are involved would be acceptable? -¿Bribing? - No.

Why not? - Because it’s wrong. - Because it’s wrong, because many people die while consuming drugs.

Because there are consequences for other people? - Yes.

This reasoning was behind the agreement on assigning lower scores to transit bribes: a lot of people are killed or injured in Peru due to transit accidents, most of which are caused by reckless drivers that bribe public officials to avoid being caught.

The second rationale that emerged looks closer to what Pavão (2018) found in focus groups conducted in Brazil: a justification that points to inevitable system failures; a system that is inefficient and corrupt and cannot be fought by an individual. Most participants with rationalizations that blame the system for corruption are men, and when women intervened was to comment or reaffirm the opinion expressed by the majority of male participants. As a young male from high SES explains,

It is not only the security sector that is affected by bribery but several ones. For example, I am doing research on formality and one of the main obstacles to foster formality is the system. The system imposes very long procedures for informals; and this makes informals pay under the table to complete their paperwork and legalize their business. This [system] forces them to bribe, but at the same time it is wrong. So, what is wrong and what is right?

In general, women labeled diverse acts of corruption and bribery as unacceptable more often than men. Women were also the first to bring up the topic of the unacceptability of the acts of corruption, and when this happened, they led the discussion towards this position. As one young woman clearly stated when talking about bribery related to traffic tickets, “the fact that these are frequent and common situations in Lima does not mean that they are acceptable for any reason. Small actions can have big repercussions.” On the contrary, more men tended to qualify and relativize their valuations to justify more some types of situations.

Another form of this rationale is a denouncement of an unfair system that works in favor of those with money or influence. It is a system that is supposed to work impartially, granting universal rights; but, in practice, it does not. This is especially true for lower SES citizens, who see money as an unfair advantage in contexts of widespread corruption. As one participant from the older low SES group mentioned,

If you have money, you can speed up bureaucratic procedures. If you want a particular information, you have to pay. Sadly, this is the way it works in Peru: those with money are those who end up winning.

This reinforces findings from a qualitative anthropological study conducted in Ayacucho, Peru: the sense of exclusion from public institutions can lead citizens to justify corruption as a fact of reality (Huber 2008). While these were the more prevalent justifications, others also stand out. More than a few interventions tried to justify corrupt behavior through mechanisms identified in moral relativism studies. For example, some participants describe police officers’ behavior as “extortive” (Mishra and Mookherjee 2013) or “abusive,” which in their eyes justified paying bribes. Examples included threats of incriminating citizens with false evidence to charge them with more serious offenses than the ones committed if they did not pay a bribe. In other cases, participants referred to moral competing claims to justify the choice to bribe or tolerate bribing. Particularly, following Huber’s findings (2008), bribing was sometimes justified as a legitimate way of helping their family, which relates to loyalty to the members of the in-group as a value (Dungan et al. 2014). Finally, it is worth mentioning that we find very few references to a cost-benefit calculus as a rationale for the justifiability of bribing. Coincidentally, these few interventions come from participants of middle and high SES.

In a nutshell, focus groups provide us with evidence showing that, despite being prevalent, bribery is a morally charged behavior, expected to be publicly condemned. Second, some participants who spontaneously use euphemisms to describe a situation feel pressured not to do so in public. Third, behavioral expectations refer to bribing as a ubiquitous practice, but participants distinguish between more and less acceptable bribing situations. A rationale that emerges from the discussion points to public system failures as a common justification for bribing; an unfair system that works in favor of those with money or influence. However, this reasoning does not apply to situations that could be harmful to others, which are less tolerated. Finally, we find preliminary evidence of an association between corruption and social status in Peru, as well as interesting variation between male and female responses. For example, participants from low SES overall considered the bribing situations more acceptable than participants from middle and high SES. At the same time, women were less open when discussing their experiences with corruption and in some cases adopted a less active role in the situations they mentioned. Male participants focused on discussing the nuances surrounding the acceptability of some corrupt acts, while women expressed more strictness when discussing this topic.

How can this contextual information help us predict group heterogeneity in SDB in the survey context across social groups? What else can we expect following the existing literature? We address these issues in the following section.

Hypotheses About Sources of SDB Heterogeneity in the Survey Context

Following our framework, we could expect that different exposure to levels (or types) of corruption across social groups and variant expectations about appropriate behavior among social referents might explain different attitudes and behaviors within society. Since social norms are subject to individual interpretation, reference social groups become important for defining the normative frames for individuals.

Focus group discussions have shown that, overall, participants from lower SES considered different types of bribery exchanges more acceptable than participants from middle and high SES. Or at least they felt more comfortable talking about their acceptability within their social group. In unequal societies, the poor are generally more dependent on the state to access basic services such as education and health (Kaufman and Nelson 2004; Huber and Stephens 2012). This closer contact with state institutions leaves lower-class citizens more exposed to bribing encounters and, possibly, more prone to normalizing it.

However, at the same time, focus group discussion subtexts show a plausible association of corruption and social status in the collective imaginary. While corruption is condemned, one of the rationales that emerges to justify bribery situations points to the existence of a profoundly inefficient and unfair system that pushes individuals to bribe. In fact, the prototypical corrupt person involved in grand corruption is collectively perceived as someone skillful from the middle to upper classes. Some condescending interventions also related lower education (empirically conflated with class in Peru) as the motivation for engaging in bribing and as an impediment for becoming a (successful) corrupt officer.

Given these associations related to class, the social distance between the survey interviewer and interviewee might spark a socially desirable answer and distort reports of past corrupt behavior when asked directly. Considering that interviewers in polling firms are usually from a middle-class background, a social status concern might be salient for low and high SES respondents. On the one hand, low SES respondents may be reluctant to admit to paying a bribe in a direct question because this will signal interviewers that they are poor enough to need it when dealing with state institutions (Oliveros and Gingerich 2020, 10). According to this interpretation, respondents from low SES might be more prone to lying than middle-class respondents when interviewed directly about past corrupt behavior in the survey context (H2a).

On the other hand, higher SES respondents might also be tempted to lie if asked directly by middle-class interviewers. Being aware that they are part of a social group that is perceived as being advantaged and powerful, able to easily “navigate” the unfair system, they might care more about being “discovered” as bribers and seen as selfish and amoral persons. They might suspect that it will be more difficult to empathize with them and understand their unethical behavior. Thus, respondents from high SES might be more prone to lying than middle-class respondents when interviewed directly about past corrupt behavior in the survey context (H2b).

Concerns about social standing might also affect male and female respondents as they seek to conform to gendered behavioral expectations that go in different directions, producing a gap in gender differences in reported corrupt behavior when direct questions are asked (H3). The expectation would be that women underreport bribes when asked directly because of social pressure to engage less in corrupt actions, while men, due to socialization, will overreport corrupt behavior when asked directly.

These expectations are based, first, on previous literature on the subject that shows that gender socialization leads to females being more likely to be influenced by social norms to create a favorable impression (Chung and Monroe 2003), making them more likely to overreport favorable behavior on surveys (Bernardi 2006). Women are also generally believed to be more honest as well as less egoistic (Fink and Boehm 2011; Borkowski and Ugras 1998), and these expectations could lead them to underreporting behaviors seen as unacceptable.

Second, these expectations also conform to what we know in Latin America about gender and corruption. In Peru, there are rooted normative expectations concerning women’s propensity to supposedly engage less than men in corrupt behavior. Consequently, women might feel socially pressured to follow these normative expectations. However, they do live in a social context where corruption is everywhere, so they might not easily avoid bribing. This could lead women to lie more when asked about having paid bribes in the past. In contrast, gender socialization in Latin America constantly puts pressure on men to “demonstrate” their masculinity (Vásquez 2013), including being bold and able to engage in risky behavior. Indeed, as focus group discussions showed, there was a consensus across social classes and age cohorts that the prototypical corrupt person in Peru is male. Hence, contexts of high prevalence of corruption, where most peers usually “dare” to bribe could lead men to overreport their past corrupt behavior when asked directly in the context of a survey.

Additionally, according to 2019 LAPOP data, younger age cohorts are more likely to be tolerant of bribery across Latin America. But it is not clear whether, as a cohort, the youngest would be prone to lying about past corrupt behavior if asked directly. Hence, although we control for age, we do not develop any specific expectation for the youngest cohort. However, focus group discussions did reveal an interesting contrast related to social class. Young participants from high SES collectively qualified bribing situations as less acceptable than young participants from other classes, but also from high SES adults. Given that it may be particularly important for this subgroup to stand up as moral persons in front of others, higher SES youngsters could lie more when asked directly (more SDB) in the survey context (H4).

List Experiment

We designed and conducted a LE-a sensitive survey technique that increases the anonymity of respondent’s answers to measure the extent of SDB. As an unobstructive measure, the LE is expected to circumvent the SDB expected when asked directly about the prevalence of socially sensitive phenomena (González-Ocantos et al. 2012; Kiewiet de Jonge 2015; Fergusson et al. 2018; Gueorguiev and Malesky 2012; Pavão 2015). This approach allows us to identify sources of bias related to respondent factors by conducting a difference in proportions test between the percentages elicited from the LE and the direct question. We also provide an analysis of an item-count technique regression for the LE and logistic regression for the direct question.

A LE was applied to a nationally representative sample of 1,215 Peruvian citizens living in cities between May 20 and 23, 2017.8 We will focus our analysis on data collected outside Lima, Peru’s capital city-a sample of 713 citizens-to consider the application method of the survey.9 From those cases, we focus on a sub-sample of 465 respondents who received the control and the treatment of “bribe.” The list of activities shown to a respondent (Control or Treatment) was chosen randomly (Figure 1).10 After showing respondents the list of activities, they were asked how many they had partaken in during the last 12 months. It was stressed that they should not focus on which ones, but how many. Aside from the LE, respondents were also asked a direct question about corrupt behavior later in the survey: “In the last 12 months, did you give a bribe to an official of a state institution, such as police, court, prosecutor, municipality, school/UGEL (Unidad de Gestión Educativa-Educational Management Unit), health center/hospital, etc.?”11

To test the expectations of H1, we focus on the global results of the LE and then compare them to the direct question. The difference between the means of the control and treatment group is interpreted as a proportion (since the difference between the two can be interpreted as the percentage that admits having participated in bribery). We also calculated the percentage of respondents from the direct question that had admitted to having engaged in bribery.

Figure 2 provides the estimated percentage of respondents that admit having participated in bribery through the LE, as well as responses to the direct question. The differences between these two measures are interpreted as an estimate of SDB. We observe that the experimental proportion for treatment is higher than the percentage obtained through the direct question, and this difference is statistically significant. Thus, confirming H1, we find evidence that SDB does take place when asking respondents directly about their past corrupt behavior in Peruvian cities outside the capital.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 2. Participation in corruption: unobtrusive and direct measures Note: The number of respondents is in brackets. * The result is significant at p<0.05 for the difference between proportions of LE and direct question. We used a two-tailed difference of proportions test.

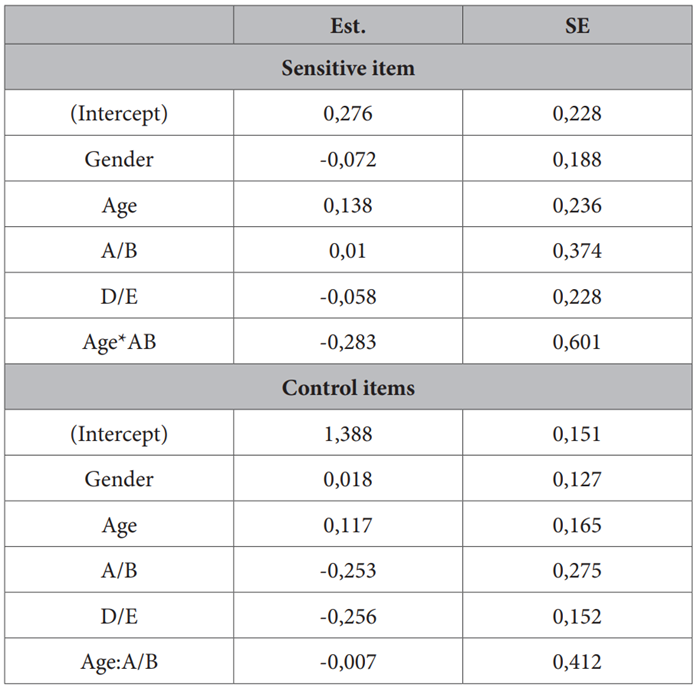

However, are there differences across subgroups in the way they answer the experimental and the direct question about their bribing behavior? To analyze whether this is the case, we compare the substantive results between the estimated effects through the item-count technique regression for the LE and the min-max scaling of the effects in a logit regression with the direct question.

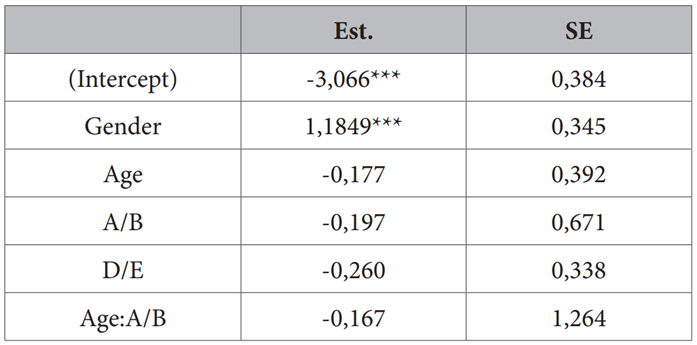

For the LE regression, the results are divided between the effects of the variables of control and the sensitive item. We will focus on the effects of the variables on the likelihood to support the sensitive item about bribing. Even though we can observe that none of the variables appear as statistically significant, we will focus on the substantive findings that emerge from the regression. For the logistic regression, which models the direct question of experience with corruption, we calculate the average marginal effects, and more specifically the min-max change. This question carries the weight of SDB, so this could help us identify specific groups in which social desirability is affecting the results of the direct question, especially if we compare them with previous results from the unobtrusive measure. In this way, the LE regression allows us to uncover the truthful effects of the sociodemographic covariates for the sensitive item, while the logistic regression is affected by SDB. We focus our analysis on contrasting the results of the unobtrusive model (LE regression) and the SDB model (Logistic regression). 12 (see figure 3 and figure 4).

Consistent with H3, male respondents report more bribe-giving than females when asked directly, but this difference disappears when using the LE technique. This implies that men overreport their past corrupt behavior when faced directly with the question, while women also underreport their actual bribing behavior in a direct question scenario. This finding is particularly relevant since this is the only covariate that is significant in the logit regression. As mentioned previously, this important finding could be linked to gendered socialization processes in Peruvian society, in which males are keener to project an image of “daring” and women of “honest” and “strict.”13

Second, although not statistically significant, we observe an interesting substantive pattern with age: younger respondents, in contrast to older ones, appear to report less bribe-giving in the direct question, while in the LE regression (sensitive item) they are more likely to report having participated in bribery. This could indicate that youngsters bribed more than older respondents but lied about it, underreporting their behavior. Even though we did not specify expectations for this covariate, this finding provides more evidence for observational studies that identify that younger age cohorts in Latin America are more tolerant towards bribery (Blake 2009; Corbacho et al. 2016).

Third, we do not find any conclusive evidence about the role SES plays in SDB. Both in the LE and in the direct question, compared to the baseline category of SES C, respondents from SES A/B and SES D/E were less likely to report having engaged in bribery. But this difference is neither big nor significant. Thus, although interesting, this finding is not enough to reject the null hypothesis. (see figure 5 and figure 6).

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 6. Logit regression (direct question) *** The result is significant at p<0.001 for the logit regression.

Finally, results remain mostly unchanged after introducing an interaction term between young age and high SES (A/B), as we can see in Figures 5 and 6.14 There is not enough evidence in favor of H4, since there is not a substantive nor significant difference in the way young high-class respondents report their bribing behavior. Nevertheless, when the interaction term for young from the high SES is introduced, the coefficient for SES A/B in the LE regression turns positive, although the coefficient is still not significant and close to zero. This may indicate that the slight underreporting of past bribing behavior originally attributed to high SES may be driven by the younger cohort of that social group.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article sought to understand the reasons why certain individuals lie about past corrupt behavior when asked directly in a survey context. We contend that in contexts with widespread corruption, conflict among different types of social norms is likely, and norm compliance becomes situation dependent. Corrupt practices are prevalent and may even be considered relatively acceptable social practices or unavoidable. Nonetheless, engaging in corruption still generates discomfort in individuals who acknowledge that some existing social and moral norms condemn it. Moreover, different levels of exposure to corruption and varying expectations about appropriate behavior across social groups might also explain different individual attitudes and behaviors towards bribing, as well as the propensity of lying about past behavior.

Together, focus groups and survey data provide evidence that supports our psychological approach. Through focus groups, we find that participants displayed a complex relationship with corruption: even though they were aware of the moral negative weight of corruption, they were also comfortable enough to detail their experiences with it. Considering the vast information that participants possessed and their willingness to share their experiences, it is not surprising that close to 40% of them identified a bribing situation when prompted with the visual stimuli of an (apparent) police officer receiving an envelope in front of a police station. In addition, participants admitted that some bribing situations (bribes for expediting procedures) are much more acceptable than others (bribes to avoid traffic infractions). Bribing is morally condemned in Peruvian society, but this stigmatization can be reframed or re-signified under specific circumstances, especially through the system failure rationale discussed in focus groups. This allows individuals to circumvent the moral sanction associated with it to lessen psychological discomfort.

This may explain why some individuals lie about their past corrupt behavior when asked directly in a survey context. Overall, we confirm that SDB is at work even in a context in which corruption is widespread like in Peru (H1). The LE estimate of respondents who engaged in corrupt behavior is higher than the proportion obtained when asked directly. Despite being so prevalent, bribing behavior is morally condemned in Peru. Focus group discussions showed this clearly when participants collectively discussed how to define corruption. Across groups, they portrayed corruption as one kind of “bad” behavior, using mostly negative adjectives to highlight it. Most participants also condemned corruption as a practice associated with “selfishness” or “convenience.”

Two main types of rationale emerged collectively to justify why, sometimes, engaging in bribing might be acceptable. First, we found a rationalization of the negative externalities of corrupt behavior. The only limit to the acceptability of bribing was explicit harm to third parties (like in corruption related to traffic infractions). This reasoning was the more prevalent one, though others also pointed to inevitable failures of a corrupt (and unfair) system that cannot be fought by an individual alone.

Some emerging literature in moral cognition points to the same direction as our research: there are cases in which unethical behavior can be motivated by moral concerns or these can be used as a mitigation rationale for the unethical behavior (Wiltermuth 2011).15 In many cases, this type of “benevolent dishonesty” (Gino and Pierce 2009) can occur when the beneficiaries of “dishonesty” induce sympathy or guilt. This resonates with our finding about the appraisal of the effects of bribing in different situations. Participants in the focus groups were mostly in consensus about the fact that the effect of bribing was more severe when it directly brought harm to others. This made it harder to empathize with this hypothetical briber.16

Hence, social desirability does exist and plays a role in contexts in which corruption is part of everyday life. However, social desirability does not work uniformly across subgroups. Different exposure to levels of corruption across social groups and variant expectations about appropriate behavior among social referents seem to explain the propensity to lying about past corrupt behavior of certain subgroups.

Most importantly, gender socialization is an important source of SDB when reporting past bribing behavior in Peru. Men actually overreport their past bribing behavior, while women lie by underreporting it. This finding is important because gender was the only statistically significant covariate in the logit regression, using the direct question. Pressure to comply with gendered normative expectations results in an important SDB gap when asked about past corrupt behavior. The focus group discussions also pointed to the existence of interesting, gendered differences in tolerance for bribing. In general, women qualified diverse acts of corruption and bribery as unacceptable more often than men. While male participants focused on discussing the nuances surrounding the acceptability of some corrupt acts, women expressed more strictness when discussing this topic. Moreover, most participants with rationalizations that blame the system for corruption were men. Women were also less open when discussing their experiences with corruption and, in some cases, they made clear that they had a less active role in alleged bribing situations, led by men.

Overall, these results underscore the importance of designing unobtrusive measures when studying the prevalence of corrupt practices in Latin American societies like Peru. Notice, for instance, that the Global Corruption Barometer (GCB), the most frequently cited measure of individual-level responses on corruption across countries, is based on direct questions. If SDB varies across societies, the GCB is distorting the behavior that it purports to measure. The GCB may also be underreporting the incidence of bribing in services in which women are already more likely to pay bribes for, such as health services and public-school education (Transparency International 2019). Furthermore, direct measures of sextortion-one of the most significant forms of gendered corruption highlighted recently by the GCP-may suffer from greater SDB.

These results also have important policy implications. For starters, it means that a gender-neutral intervention to fight bribery would not be effective, as it will simply reproduce gendered expectations regarding corrupt behavior. To design more effective policy interventions, future studies should thus deepen our understanding about this gender source of SDB when reporting past corrupt behavior. To begin, it would be important to assess whether women are more likely to underreport bribery across other countries with higher levels of corruption in Latin America. Recall that Gingerich and Oliveros (2019) find that women are not more likely to lie about engaging in corrupt acts than men in Costa Rica, a country with lower overall levels of corruption in the region. It may be that contextual levels of corruption are what drive gender SDB. Moreover, an experimental survey design could be developed to test whether men actually feel rewarded in some of their circles by overreporting bribery.

In addition, although not statistically significant, we find substantive evidence regarding age that merits further discussion and research. Other things equal, young respondents bribed more than older ones but lied about it, actually underreporting their behavior. Although not theoretically expected nor statistically significant, this finding confirms what some observational studies have noticed in the region. As corruption becomes more widespread and normalized, younger citizens, who have been socialized in this context, become more tolerant or even willing to engage in bribing (Blake 2009; Corbacho et al. 2016). Finally, our lack of substantive and significant results regarding the role of SES on SBD does match the uncertainty highlighted in previous studies, where SES (or close proxies like education) had a mixed role when it came to the report of past engagement in bribery. This finding is important considering that existing studies about bribing in Peru are based on direct measures of victimization and conclude that citizens from higher SES are more likely to bribe than citizens from low SES (Hunt 2007; Yamada and Montero 2011).