Introduction

The drug policy arena has recently developed into a highly diverse and contested playing field across Latin America. While Uruguay became the first country to fully legalize the production, distribution, and recreational use of marijuana-possibly, soon to be followed by Mexico-other countries such as Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela have stayed firmly within the traditional prohibitionist framework. Another group of states, including Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, all of which had undertaken steps to incorporate more flexible and less repressive measures to handle drug-related challenges, have recently returned to a more prohibitionist approach.

Given the centrality of drug-related challenges to Latin American societies, including those associated with organized crime, it is not surprising that multiple new country studies, as well as some comparative works, have shown interest in analyzing the dynamics within licit and illicit drug markets, the content of recent drug policies, and the politics behind changes in policies (Bagley and Rosen 2015; Labate, Cavnar, and Rodrigues 2016; Gootenberg 2017, among others). Because of its importance, Uruguay’s far-reaching reform of legalizing and regulating the marijuana market has received particular attention (Garat 2015; Müller Sienra and Draper 2017; Queirolo 2020; Queirolo et al. 2019; von Hoffmann 2016 and 2020). These studies generally share the view that the “war on drugs” and prohibition-defined here as the penalization of any activity that facilitates drug consumption, except for medical and scientific purposes-constitute a paramount failure. This is not only the case because prohibition has been unable to contain drug production and consumption, but also because prohibition empowers criminal actors, which derive a large part of their income from the illicit drug trade (Garat 2021).1

Yet, despite the multiplicity of academic studies about recent drug policy dynamics, there has been relatively little development of theories, analytical models, or “theory-guided comparisons” (Durán-Martínez 2017, 149). This is problematic because the drug policy field is full of intriguing puzzles that could benefit from theoretical analyses. For instance, why are most governments from Latin America holding on or returning to antiquated, prohibitionist policy models despite their evident failure and an international context that has become more amenable to change? What factors enable more flexible drug policies based on harm reduction2 and public health, as has occurred in several countries since the 2000s? Or, in more general terms, what factors can account for the differences in drug policy choices across Latin America?

Of the few works that explicitly apply theoretical tools, most have prioritized the role of the United States in the “war on drugs” (Borda Guzmán 2002; Cepeda Másmela and Tickner 2017; Nadelmann 1990; Pérez Ricart 2018; Vorobyeva 2015). While these works have highlighted important power dynamics of the “war on drugs,” they also neglect the agency of Latin American actors in strengthening the prohibitionist paradigm (Campos 2012; Molano Cruz 2017 and 2019). Furthermore, they cannot account for different policy choices within the drug-war context. For instance, why did Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela decide to criminalize the possession of drugs (even for personal consumption) in the 1970s, while Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay did not? Or why did only Colombia apply aerial spraying to diminish coca crops, but not Bolivia and Peru? Although Cepeda Másmela and Tickner’s (2017) use of securitization theory explores the possibilities of desecuritizing the drugs issue in Latin America, their contribution does not explore the factors that can explain different policy choices across the region.

To go beyond the premise that drug prohibition had been imposed exclusively by the United States and better understand the politics of drug policies in Latin America, Rodrigues and Labate (2016 and 2019) developed an innovative theoretical and methodological tool called narcoanálisis. Influenced by the Foucauldian concepts of genealogy and biopolitics, it claims that drug prohibition constitutes a technique of controlling urban populations to assure that individuals remain functional participants in the industrializing economies and to impose a degree of order in the growing urban hubs. Furthermore, they argue that drug prohibition can be understood through the juxtaposition of five dimensions or “analytical levels”: moral, health, public safety, national security, and international security (Rodrigues and Labate 2019, 42-45).

For several reasons, the narcoanálisis approach provides a refreshing outlook on Latin America’s drug policy dynamics. First, as the authors’ historical analysis stretches back to the late nineteenth century, it employs a more extended timeframe than most studies. Hence, the framework seeks to interrogate different stages and developments of drug prohibition, long before US President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in 1971 and the militarization of drug policies in the 1980s. Second, they view prohibition as a “two-level articulation between domestic social and political practices and an international repressive model” (Rodrigues and Labate 2016, 12). Thereby, the approach explicitly recognizes the agency and importance of Latin American actors in the definition and implementation of drug-war policies. Third, their five analytical dimensions, or “levels of analysis,” identify a variety of arguments and discourses in favor of drug prohibition, which is helpful to obtain a more complete understanding of past and present drug policy debates across different national contexts.

Despite these advantages, the narcoanálisis framework also has some limitations. First and foremost, by grounding the approach in biopolitics, it has a relatively static view of Latin American elites and their interests. This is problematic because many of the recent initiatives to desecuritize drug-related challenges and achieve more flexible policies have come from representatives of the region’s policy elites, such as the former Uruguayan President Jorge Battle in the early 2000s (see below) or the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy almost a decade later (CLSDD 2009). Furthermore, while narcoanálisis aspires to trace and make sense of the complex social interactions that have accompanied and enabled prohibitionist and repressive policy models, it does not give researchers any concrete tools to identify why governments opted for specific drug policy choices at a particular moment, except for the relatively loose notion that government policies are shaped by discourses and practices of power and political interests called “upward vectors” (Rodrigues and Labate 2016, 15). Similarly, although the authors highlight the importance of “an international repressive model,” they do not explain or theorize how inter- or transnational actors affect drug policy choices.

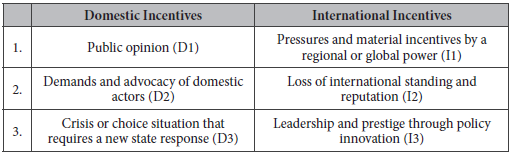

While these limitations can be overcome by sound empirical analysis, the present article upholds that a clear outline of the mechanisms through which national and international contexts affect drug policy choices could significantly improve research about these policies. With this goal in mind, the first part of this article develops an alternative and complementary theoretical approach, called the Psychoactive Politics Framework (PPF), which describes how shared views about the use of psychoactive substances and collective expectations about drug policies generate six types of political incentives that affect policies about these substances and their users in various ways. The PPF is grounded in the rationalist view that policy makers respond to national and international incentives related to political power. As outlined below, this is because policy choices about the production, commerce, and use of drugs or, more precisely, psychoactive substances3 affect broader political goals such as gaining popularity, winning elections, material benefits, international standing, and prestige. Therefore, drug policy choices are likely to result from national and international incentives, which will help policy makers achieve these objectives. These are primarily incentives related to public opinion, advocacy, crises, pressure, standing, and leadership.

While section 4 provides some orientation about the relative importance of different incentives, the PPF does not go all the way in ranking them according to their capacity to influence policy outcomes. The above because their specific relevance is contingent on a variety of additional factors, including the role of a country in the international drug trade, the characteristics of the political system, country size, and the political goals particular governments prioritize over others. Yet, the PPF can be seen as a steppingstone to develop more precise theories that explain under what conditions specific types of incentives are likely to be more influential. Nevertheless, this goes beyond what this article can offer. Instead, it proposes a theoretical argument about how drug policies relate to morality and power while providing straightforward guidance about the political incentives that researchers should look at when analyzing drug policy choices.

In an exercise to highlight the framework’s utility, the second part of the article (sections 4 to 7) uses it to explain Peru’s first legal framework to eradicate illicit coca crops: the Decree Law 22095 of 1978. An examination of embassy cables, protocols of diplomatic meetings, and media sources not only reveals that this policy reform was the result of clear political incentives, but also illustrates how US drug control agents achieved some of their policy goals in the early stages of the “war on drugs.” Before passing the law, representatives of the embassy and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) manipulated the national incentive structure by forging alliances and offering resources to important national players, such as the Ministry of the Interior, the Investigative Police, and the attorney general. Over time, these actors changed the government’s reluctant stance toward coca eradication. Hence, although an increasingly prohibitionist international context favored the reform, the advocacy of key domestic players was decisive in shifting the country’s policy. The case study also shows that the government’s actual views about drugs and coca mattered relatively little in explaining their policy choices. Before analyzing the Peruvian case, the following sections outline the PPF’s ingredients and provide some guidance on its application.

Drug policy as a question of power

The present section argues that the principal drivers of drug policy choices are political incentives tied to considerations about power, elections, prestige, and material benefits. This argument is based on the assumption that several national, international, and transnational actors have strong feelings and interests attached to psychoactive drugs and their associated challenges (mainly drug consumption and organized crime). What this means is that policy makers cannot simply act according to their beliefs, values, and ideas or do what they think is best for their societies. Instead, when politicians consider changing a country’s drug policy, they inevitably have to think about how these policies will affect broader political goals, such as remaining popular, staying in office, and maintaining or improving the international standing of their countries. In this sense, if politicians hang on to failed policy models, it is not necessarily because they do not understand their shortcomings and the dynamics of illicit drug markets (although this might well be the case), but primarily because they fear that changing prohibitionist policies would generate serious political repercussions.

An illustrative example of this dynamic is the brief campaign in favor of drug legalization by Uruguay’s former president Jorge Batlle (2000-2005). At the beginning of his term, he argued that legalizing drugs was a better option than prohibition, since it was the most effective way to get rid of organized crime and drug-related violence (“Battle insiste con liberalizar” 2000). Yet, his ideas about drugs neither gained traction nor did they materialize into any concrete policy proposals. The other way around, when policy changes do occur, we can expect them to be driven by political incentives that will help policy makers hold on to power, remain popular, obtain material benefits, and maintain or improve their countries’ international standing. These incentives are strongly shaped by a combination of moral considerations and transnational dynamics, which are outlined in the following paragraphs.

As it is well known, many drug policy debates and discourses evolve around deeply held collective beliefs about right and wrong, appropriate and inappropriate behaviors, pleasure and danger, and fears of what could happen if drug use would suddenly increase. For instance, many individuals and prominent social and political actors believe that recreational drug use is inherently bad, dangerous, and immoral. What follows from this assumption is that governments should do everything within their power to undermine recreational drug use, which is often labeled as abuse.4 A less prominent viewpoint believes that the consumption of recreational drugs is an issue of personal freedom in which the state should not interfere. A more popular notion expects governments not to criminalize drug consumption and assist addicts through health, psychological, and social services. As highlighted by the vast literature on intersubjective international norms, once shared expectations about the appropriate behavior of governments gain traction, they can exert significant pressure and alter political incentives (Cortell and Davis 2000; Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Towns 2010).

While this moral dimension has elements in common with other areas that touch upon the relationships between the state, society, and the individual-such as rights about political freedoms, safe abortions, and sexual preferences-drug policies are shaped by a particularly strong transnational dynamic. In other words, how each government deals with its drug-related challenges has consequences in other countries. For instance, a tolerant approach towards the activities that facilitate the production and use of narcotics enable their supply elsewhere. Yet, as highlighted by the history of balloon and cockroach effects, if a country decides to step up its response against criminal activities, illicit networks usually move elsewhere.5 Hence, governments, parties, social movements, NGOs, religious groups, academics, and journalists do not evaluate other countries’ policies only on moral grounds, but also because they fear that what happens elsewhere may directly or indirectly affect them.

This unique combination of moral and transnational considerations has stimulated high levels of political activism, which have constrained, facilitated, and incentivized drug policy choices at the global, regional, and national levels (McAllister 2000; Musto 1999; Thoumi 2011; von Hoffman 2016). In this sense, when political activism, advocacy, and pressure in favor of a particular policy model rise, we are likely to witness more policy changes according to the model’s parameters. This is because the consolidation of support in favor or against a particular policy model alters the incentives and cost-benefit calculations of politicians who seek to hold on to power, remain popular, obtain material benefits, and maintain or improve their countries’ international standing. In South America, strong examples of how political support and pressure have generated patterns of policy changes are the waves of prohibitionist drug policy reforms during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, as well as the design and implementation of more flexible policies in the 2000s (Labate, Cavnar, and Rodrigues 2016). Yet, to obtain a more precise understanding of how these developments happen and, importantly, why some changes only take place in some countries but not in others, a more detailed look at the incentives and constraints of each government is needed.

The fact that this article prioritizes power-based incentives does not mean that the personal or shared values, beliefs, and ideas of decision makers are unimportant. In the absence of clear national and international incentives, policy makers’ personal or inter-subjective characteristics are crucial to the analysis as they face fewer restrictions to act according to their preferences. This is also the case when strong incentives in favor and against a policy coexist. Yet, all of this reinforces the argument that a close examination of the national and international incentive structure provides the best starting point to analyze past and present drug policy choices. Therefore, the following sections outline the three most important national and international incentives that have the potential to drive drug policy decisions.

Domestic incentives: public opinion, advocacy, and crises

At the national level, changes in drug policies are likely to respond to three types of incentives. In the first place, as governments have a clear interest in remaining popular and winning upcoming elections, a policy change may reflect, or try to please, the overall preferences of the public (incentive D1). As mentioned above, most citizens have strong views about the production, sale, and use of psychoactive substances for recreational purposes. Therefore, we can assume that governments have a strong incentive to design and implement policies that are popular in their societies. An example is the current wave of legalizing medical and recreational marijuana in the United States, which has been driven by public support and referenda (Queirolo et al. 2019, 1314). The other way around, going against the public’s will carries the risk of losing popularity or votes in upcoming elections. For instance, legalizing or decriminalizing a drug in a society that prefers prohibition and punishment may result in high political costs.6 Therefore, researchers who want to explain drug policy changes should pay special attention to tendencies in public opinion.7

The second crucial element of the domestic incentive structure are the demands of important political and social actors (incentive D2). The drug policy field is composed of multiple players, including political parties; parts of the state apparatus, such as the police, the military, the ministry of the interior, and specialized government agencies to tackle drug-related challenges; religious groups; NGOs and social movements; media outlets; and policy experts and epistemic communities. Particularly relevant are those actors that have the potential to affect the functioning of the state or the political survival of a government.

In Ecuador, for instance, the police and the minister of the interior, José Serrano (2011-2016), spoke out against a drug policy reform in 2014, which had lowered the penalties for low-level drug offenses (Ortega 2014; Ortiz 2015). Subsequently, the government of Rafael Correa (2007-2017) returned to a more prohibitionist stance on drug possession and other low-level drug offenses (Paladines 2016). A similar dynamic occurred in Peru in 2011 after Ricardo Soberón, the former head of the National Agency for Development and Life Without Drugs (DEVIDA, for its Spanish acronym), had announced a stop to the country’s coca eradication program for an indefinite time to reexamine its utility (Reuters Staff 2011). The decision was criticized immediately by sectors of the opposition and popular media outlets. Just a week later, Oscar Valdés, the country’s minister of the interior and former army officer, announced a return to forced eradication, and Soberón left his post at DEVIDA a few months later (Stone 2012).

The abovementioned dynamics illustrate that research needs to pay close attention to drug policy debates and developments at the national level. Even though not all these debates and decisions take place in the public, most actors in the field not only try to influence decisions directly but also affect changes in public opinion. Therefore, many of the players involved leave large trails of communication that researchers can analyze to obtain a better understanding of the incentives and constraints that policy makers face.

Although public opinion and the advocacy of political and social actors cover a significant part of the national incentive structure, there exists another type of dynamic that may compel governments to change a policy. Sometimes policy makers are confronted with a challenge or crisis, which incentivizes them to act and respond in unprecedented ways (for example, a sudden increase in drug consumption; the emergence of a new drug; the spread of a criminal network; an increase in drug-related violence; etc. [incentive D3]). While in some cases, crises or unprecedented events have the potential to alter the views and preferences of the public and important domestic actors, in others, these situations incentivize or offer “windows of opportunity” to address challenges creatively or to push for an otherwise controversial policy.

The clearest example of this logic is the legalization of recreational marijuana in Uruguay in 2013 (Queirolo et al. 2019). The reform was not supported by public opinion, nor was it part of the government agenda until three unrelated killings shocked and mobilized citizens of the capital Montevideo. Subsequently, the Mujica government (2010-2015) established an ad-hoc Security Cabinet, composed of six ministers and several government officials, which met at least ten times in the weeks after the killings to discuss how to respond to the perception of public insecurity. According to the reconstruction of these meetings by Müller Sienra and Draper (2017, 108-115), police agents reported the increasing role of drug traffickers, their strategies to exercise control through threats and intimidation, and the use of assassinations to resolve disputes with other groups. Members of the cabinet concluded that an effective way to lower the influence of organized crime was to take the marijuana market out of their hands, which was the starting point for a long political campaign in favor of the measure.

The domestic nature of the incentives discussed above does not mean that they are free from international or transnational developments. National drug policy debates do not occur in a vacuum but are shaped by global and regional discussions, as well as processes of norm advocacy and contestation (Bloomfield 2016; Nadelmann 1990, 482; Keck and Sikkink 1999; Klotz 1995). Furthermore, foreign actors have a variety of tools and resources through which they can empower national actors and, thereby, manipulate national incentives (Castro 2015; Müller Sienra and Draper 2017, 135-190; Pérez Ricart 2018; von Hoffman 2016). Yet, what matters is that in each mechanism outlined in this part, policy makers are concerned about the national context. The following section illustrates that the international context provides another set of incentives, which are likely to be considered by national power holders.

International incentives: pressure, standing, and leadership

Similar to the previous section, the present one illustrates three political incentives that are particularly important to explain drug policy changes. First, governments may decide to adopt a new policy because it reflects the interests of the most powerful state, or group of states, in a specific region (incentive I1). As explained above, drug control and prohibition has been a high priority item on the foreign policy agenda of the United States towards Latin America since the 1970s, although its specific importance has varied across different times (Carpenter 2003). Thus, complying with US interests was key to maintaining a favorable bilateral relationship. Moreover, (non)compliance had direct material consequences. Since 1986, the so-called certification procedure allowed the US Congress to penalize countries that did not cooperate fully in the “war on drugs” if the US president had recommended so. For instance, it could suspend up to 50% of all financial aids for a fiscal year; stop all aids for the following years; and require US representatives in multilateral development banks to vote against granting loans to the offending country. Further sanctions could include the suspension of the World Trade Organization’s most favored nations clause; the imposition of tariffs of up to 50%; and the restriction of air trafficking between the United States and the offending country (Carpenter 2003, 125-126). However, the United States not only relied on negative incentives such as threatening decertification. Cooperation in the “war on drugs” also provided access to trade benefits through the Andean Trade Preference Act (ATPA), enacted in 1991, which eliminated tariffs for 5,600 products from Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. This measure was extended and complemented in 2002 by the Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Act (ATPDEA), which liberalized trade for another 700 products (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2002).

Apart from material repercussions related to inter-state power dynamics, policy changes may also result from a state’s fear of losing its international standing and reputation (incentive I2). As outlined by the vast literature on international norms, this is most likely the case when a policy model, such as prohibition, is deeply ingrained in the identity of a group of states or enjoys high levels of acceptance and support within the international community.8 In such cases, norms can exert significant political pressure to conform to their parameters.9 This dynamic is potentiated even further if the policies adapted by a state are perceived to affect developments in other states.

When applying this logic to the drug policy field, the decade-long dominance of prohibition in the international community, combined with the view that insufficient controls create problems for all others, made it harder for countries to implement policies that deviated too much from the prohibitionist norm. The other way around, the more recent declining prominence of prohibition and the “war on drugs” in Latin America, as well as the rising prominence of harm reduction as an alternative policy framework, have decreased the political costs of implementing alternative drug policies (von Hoffman 2016).

A third and last type of incentives arises through the possibility of gaining prestige by becoming a policy leader and innovator (incentive I3). This incentive is particularly strong when an old policy model is experiencing a crisis or when a new one is still in its early stages. For instance, given the expert consensus that the traditional policy model of “war on drugs” is not working (Bagley and Rosen 2015), a country that can successfully implement alternative policies might be able to offer guidance and function as a model for others. Such a leadership role may help a country increase its international standing and prestige, despite lacking material resources. Uruguay’s decision to become the first country to legalize and regulate recreational marijuana can be interpreted this way since it has led to a wave of positive reporting among liberal news media (The Economist 2013), despite heavy criticisms by the United Nations International Narcotics Board (Jelsma 2013).

After discussing the most important domestic and international incentives that may induce governments to change their drug policies (see Figure 1 for a summary), the following section provides some guidance on how this framework can be applied.

Applying the PPF

As highlighted above, the PPF assumes that drug policy changes are driven by political incentives rather than policy makers’ beliefs and ideas or expert views about drugs and their associated challenges. The above because drug policy choices have the potential to strongly affect broader political goals, such as popularity, electoral success, material benefits, prestige, and international standing. Although, under certain conditions, each incentive outlined above constitutes a possible cause or pathway for a policy change, it is logical that the more incentives there are in favor of a particular policy, the more the likelihood that it will happen. Moreover, as a government’s goal to stay in power usually outweighs the objective of maintaining good international standing and relationships, domestic incentives are likely to be more important. Strong public support in favor or against a particular policy model is arguably the most solid incentive. Yet, in cases where public opinion is divided or when it is unclear what the public thinks, incentives D2 and D3 can be expected to rise in importance. In any case, a strong domestic position in favor or against a policy model, supported by public opinion and the most relevant political actors, should be able to counteract international pressure. However, once this domestic position gets weaker and views about drugs become more divided or polarized, international incentives will be more relevant. For instance, in the early 1970s, South American societies did not yet view drug use as a serious problem (Castro 2015; Manzano 2015). Nevertheless, when governments started applying more prohibitionist and repressive drug policies, there was no general opposition against these policies in most countries, except in Bolivia and Peru, where the use of coca was embedded in local customs and traditions. Yet, as highlighted by the following case study, once media outlets and key domestic actors started to support prohibitionist drug policies, the government finally gave in.

Despite this broad orientation, the relative importance of different incentives is never set in stone, as there are too many factors which can alter how each one affects certain governments at a given moment. For instance, presidents without the possibility of staying in office might be more willing to go against the views of the public and important national actors. Furthermore, while researchers can make general arguments about how restrictive or flexible the international context is at a precise moment, not all governments have been exposed to the same levels of pressure at a particular time. In fact, countries that play a greater role in the production and transportation of illicit psychoactive substances are likely to experience more international pressure and efforts by foreign actors to manipulate domestic incentives. Ultimately, as smaller states with fewer resources are likely to be more vulnerable to outside influences and depend to a higher degree on cooperation, they are more likely to respond to international incentives than very resourceful states.

Given that there are multiple factors that can affect how governments react to each incentive, the PPF can be used as a stepping stone to develop more detailed theoretical claims that explain under what conditions specific types of incentives are likely to be more influential.10 A more straightforward way, however, is to use it as a theory-driven research strategy and toolkit to investigate specific policy choices or trends across different states. In this case, the relative importance of particular incentives is not assumed a priori but detected through in-depth research. A close analysis of the process and sequence of events that have preceded major policy changes enables researchers to gather evidence in favor or against each of the incentives, thereby detecting which of them mattered, how they interacted, and which ones were more important than others. To reconstruct which one of these incentives induced governments to change their policies at a given moment, researchers can draw from a wide range of sources: public opinion data; the communicative trails of the actors involved in the debates on drug policy (policy briefs, position papers, statements to the public, social media accounts, etc.); newspaper articles and media reports; parliamentary debates and protocols of parliamentary commissions; messages of diplomats; expert interviews; and secondary sources. To highlight the PPF’s utility and provide some guidance on its application, the following sections use it to analyze Peru’s Decree Law 22095, which was redacted by a small group of officials of the “revolutionary” military government and approved by its cabinet, the Council of Ministers, on February 21, 1978.11 The law is an intriguing case not only because it was Peru’s first major drug policy reform since 1949, but also because it locked the country into a long and ongoing struggle against illicit coca plantations.

Prior to the reform, Peruvian leaders had resisted implementing international agreements that would commit the government to reduce coca crops, despite growing international pressure. This was hardly the case because the Peruvian government defended traditional practices of using coca. According to Gootenberg (2008, 135-145), the rising usage of coca between 1920 and 1950 reinforced existing anti-coca sentiments and stereotypes within Peru, whose elite tended to view its use as primitive and backward. This came to light, for example, at the 1972 South American Governmental Expert Meeting on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, in Buenos Aires, which paved the way for the South American Agreement on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (ASEP, for its acronym in Spanish). According to Peru’s delegate Espinoza Barrón: “There are seven million indigenous people in Peru who chew coca (‘coquean’), which degrades them and does not allow them to produce even the most necessary to feed and dress themselves.”12 Another Peruvian representative, Esquivel Trigoso, stated that his government was seeking to reduce the use of “this stimulant” and had dictated measures to control its production. He also confirmed that social workers and teachers were trying to convince children and adolescents not to use coca.13 Nevertheless, a year later, at the Plenipotentiary Conference on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, once again in Buenos Aires, Peru’s representatives stated that they could not give their approval to any legal commitment related to the eradication, limitation, or the destruction of plants.14 This changed, however, in 1978. This year, Peru became the last member of ASEP among all South American countries. Moreover, its government committed the country to coca eradication and to combat the drug trade and consumption, through the Decree Law 22095. The next section provides a summary of the law’s content, followed by an explanation of this reform, based on the military government’s political incentives. Although the analysis shows that US involvement was crucial, it first had to obtain the support of key domestic actors within Peru’s state apparatus, such as the Ministry of the Interior, the Investigative Police, and the attorney general. These actors enabled the passing of the reform in an otherwise restrictive national context, which resisted international pressure for a considerable time.

Peru’s Decree Law 22095 of 1978

In the introductory paragraphs, the new legislation defined the production, consumption, internal and external commercialization, and coca leaf chewing as grave social problems that needed to be overcome by an efficient and holistic plan of action. Furthermore, it emphasized that drug addiction constituted a serious problem of public health, a danger for the family, and one of the primary causes of the physical and mental destruction of human beings; that the repression of the illicit drug trade and improper drug use was part of the moralizing role of the state, which ought to norm, control, and sanction all activities that help develop drug trafficking; and that all actions should aim to comply with international conventions, especially regarding the progressive eradication of coca cultivations, with the exception of industrial, medical, and scientific uses. To take on these challenges, the law prohibited cultivating new coca crops (art. 31) and established that only the National Coca Company (ENACO, for its initials in Spanish) could grow, distribute, and sell coca nationally (art. 33 and 41). Furthermore, art. 35 specified that the state would decommission the estates and properties of illegal coca growers within two to three years.

Apart from the contentious issue of illicit coca, the law criminalized several drug-related activities and defined their penalties. These included internment (internamiento) for an undetermined time for promoting, organizing, financing, or directing groups dedicated to the illicit trafficking of drugs between Peru and other countries (art. 55); no less than 15 years of prison for membership in international trafficking organizations (art. 56); and at least ten years for administering and selling drugs to individuals under 18, using violence or fraud when administering drugs, employing minors to commit drug-related crimes, and commercializing drugs in educational and social rehabilitation centers (art. 57). Even though the new law did not criminalize the use of drugs, it established that recurring drug addicts would be sent to a stationary treatment facility until they were cured. Art. 27 also reserved the right for the judge to issue embargos on the possessions of addicts to pay for the costs of their treatment.

Furthermore, the reform created two new government institutions: the Executive Office of Drug Control (Oficina Ejecutiva de Control de Drogas) and the Multisectoral Ministerial Committee for Drug Control (Comité Multisectorial de Control de Drogas), presided by the minister of the interior, and composed of the ministers of agriculture and alimentation, industry, commerce, tourism, and integration, education, and health, as well as a member of the Supreme Court (art. 3). While the former body was primarily responsible for the law’s implementation, the latter established new guidelines and oversaw the work of the Executive Office.

The above summary of the law indicates that Peru joined the “war on drugs” and the international campaign to eradicate coca with a solid legal commitment, quite contrary to the governmental position at the beginning of the decade (see above). Although the international context provided strong incentives for the reform, the following sections illustrate how Peru’s drug law reform can be best explained through the advocacy of important national actors, such as the Ministry of the Interior, the attorney general, and different police units, all of which with close ties to the US embassy and the DEA. Hence, over a period of several years, US drug control agents manipulated the domestic incentive structure by forging strategic alliances with national actors that supported drug prohibition and coca eradication.

International incentives

The international context of the 1970s provided solid incentives for prohibitionist drug policy reforms in South America. As it is well known, in 1971, US President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” soon to be followed by the creation of the DEA and increased drug control efforts abroad (Castro 2015, 87-89). Moreover, the member states of the United Nations concluded negotiations for two treaties, which prescribed new global drug control standards: the Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1971 and the 1972 Protocol amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. At the regional level, Argentina gathered its South American peers for two conferences in Buenos Aires, in 1972 and 1973, to coordinate regional drug control mechanisms and establish ASEP.

Hence, within this increasingly restrictive and prohibitionist international context, South American states simultaneously faced pressure from the United States (incentive I1) and the prospect of losing international standing through non-compliance with the new guidelines of the UN drugs control regime and ASEP (I2). Moreover, there were some possibilities of claiming a leadership role by becoming a champion of drug prohibition (I3). Direct bilateral pressure of the United States (I1) was arguably stronger during the first part of the decade. After Richard Nixon left the office in 1974, the presidencies of Gerald Ford (1974-1977) and Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) did not make drug control a top priority (Carpenter 2003, 15-18), although the DEA kept pushing for stricter control efforts throughout the entire decade (Pérez Ricart 2018). Peru, however, was a tough ground for the United States, as highlighted by the following report by US Ambassador Dean:

The GOP does not view coca growing as a problem affecting the Peruvian people. Peruvian youth do not sniff cocaine in any substantial quantity. The local campesino custom of chewing coca leaves extends back to an epoch before recorded Peruvian history. While a GOP sponsored agricultural conference has recently issued a vague [call] for the eradication of this age-old custom as being “anti-revolutionary,” there has been little evidence of a commitment on part of GOP to actively seek a reduction in coca cultivation. Moreover, cocaine traffickers have traditionally gotten off with only limited fines and jail terms in Peruvian courts, and a few police officers and GOP personnel have been caught in protection of or outright involvement in trafficking activities.15

On top of these difficulties, the United States failed to obtain permission to create a regional DEA office in Lima.16 Peru also rejected the possibility of increasing DEA staff “because of the political sensitivity in this country which has been exacerbated by the current publicity about alleged CIA involvement in internal affairs of other Latin countries,” according to Ambassador Dean.17 These difficulties indicate that US proposals and pressure alone could not change Peru’s stance on coca crops and illicit drugs. Yet, as mentioned above, the international context provided further incentives for a prohibitionist drug policy reform.

Throughout the decade, Argentina (1974), Bolivia (1976), Brazil (1976), Chile (1973), Colombia (1974), Ecuador (1974 and 1978), and Uruguay (1974) enacted new drug laws, which implemented the new global and regional standards of the UN conventions and ASEP’s First Additional Protocol.18 Without following suit, Peru would have faced the prospect of losing international standing both globally and within its region (incentive I2). Communication between Peru’s embassy in Buenos Aires and the Foreign Ministry (FM) provides some evidence of these concerns. Since 1973, the country’s embassy in Buenos Aires sent the FM in Lima several reports about ASEP, urging it to consider becoming a member.19 In 1978, the embassy in Buenos Aires took great lengths to explain ASEP to the FM, highlighting that, on several occasions, Argentina had expressed interest in Peru becoming a member, which it finally did later in the same year.20 Yet, as shown below, national actors such as the Investigative Police and the Ministry of the Interior, which became close allies of the United States, played a more decisive role in determining Peru’s drug policy. Before analyzing the manipulation of the national context by US agents, the following paragraph briefly explains why the incentives I3, D1, and D3 were less decisive.

While the shifting international context in the early 1970s provided some incentives to take on a leadership role by becoming a champion of prohibition and coordinating regional action, this role had already been claimed by Argentina, which organized the international conferences that led to the establishment of ASEP. Furthermore, as highlighted in the ambassador’s quote above, at the beginning of the 1970s, drug use was not considered a serious problem in Peru’s society, while the opposition to imposing limits on coca production was strong. However, the perception about drug consumption began to change slightly towards the end of the decade. In 1976, the Peruvian press reported on establishing an anti-drug youth brigade to protect high-school students from drug use. The same press report stated that the consumption of coca paste had increased greatly among Peruvian middle-class youth.21 On February 22, 1978, shortly before the new law was published, El Comercio-one of Peru’s most influential newspapers-published an op-ed denouncing the “universalization” of drug addiction and the impunity of the sales of narcotics to the country’s “innocent” youth, while demanding a tougher stance by the state against drug trafficking (“Tráfico ilícito de estupefacientes” 1978). Even though the state-controlled media might have exaggerated these reports to justify the new policy, the US embassy kept informing about rising levels of drug consumption and increasing arrests of drug users throughout 1978, after the government had passed the law.22 In December 1978, the US embassy stated: “The Peruvian government and the urban populace recognize increasingly that illicit drug trafficking and drug abuse are real domestic problems for the country.”23 While the apparently rising levels of drug consumption and the changing perception (corresponding to incentives D1 and D3) help explain why the state saw itself compelled to tighten its legal framework, the following analysis shows that the advocacy of powerful domestic actors, with strong ties to the US anti-narcotics apparatus, provided an even stronger force for the country’s drug policy reform (incentive D2).

How the United States gained Peru’s support

Given the limitations of influencing Peru’s drug and coca policy directly, in 1975 Ambassador Dean proposed a more modest approach, when discussing future strategy with other State Department officials: “we should not be overly critical of efforts of lesser-developed countries to control drug abuse and traffic. We must continue to stimulate, guide and support these efforts with equipment, techniques, information and international meetings but within the very real limitations and idiosyncrasies posed by the law enforcement, educational and political environments within these countries. To do otherwise would be self-defeating.”24 He also recommended taking into consideration the host governments’ concerns and interests: “I also strongly support embassy Quito’s emphasis on taking into account the special concerns and approaches of our host governments in their anti-drug programs. By supporting and reflecting these concerns in our actions we have a better chance of engaging these countries in programs of highest priority to ourselves.”25

To put this strategy into practice, US agents identified and strengthened cooperation with key domestic actors, such as several ministers of the interior, the attorney general, and the Civil Guard (GC, for its initials in Spanish), a military-style police force. Their principal institutional ally, however, was Peru’s Investigative Police (PIP). In discussions with US authorities, PIP’s head, Alfonso Rivera Santander, complained in 1976 that the Peruvian government was not really committed to eradicating coca. He also recommended that his unit should assist ENACO in supervising coca plantations and, a year later, suggested a new enforcement effort in the northern town of Cajamarca.26 This close relationship was strengthened by the fact that PIP became a sizable recipient of US anti-narcotics support, which included regular participations in DEA training courses in Washington DC, new communications and audio-visual equipment, and financial support for special investigations outside the country’s capital.27 When US officials asked PIP’s leadership in June 1974 what they needed to enhance their enforcement capacities, it mentioned help in improving their records management and updating their criminal laboratory.28 When asked again in 1977, PIP suggested “additional US scholarships, instructional material for training, the construction of a separate facility for PIP drug control operations, and a variety of electronic equipment (including phone monitoring gear), investigative material, radios, office equipment, […] transport vehicles including one light aircraft and one helicopter, 24 cars and trucks, and motorcycles.”29 To accommodate these requests, the US embassy offered Peruvian officials a step-by-step approach. Such an approach would “test the depth of any GOP commitment and also move matters toward [an] overall GOP plan that we could support financially and technically.”30

The US anti-narcotics allies within Peru’s government underlined their commitment in several ways. First, in August of 1975, Pedro Richter Prada, the minister of the interior (1971-1975), elevated the Narcotics Investigation Division within PIP to the directorate level. This allowed the division to create specialized drug enforcement units outside of Lima.31 Second, during the decade, PIP’s Narcotics Investigation Division grew from 28 to 130 agents.32 Third, despite serious doubts about his intentions and clout, Peru’s attorney general, Nelson Díaz Pomar, campaigned within the government for a revision of the country’s drug laws and an official proposal to reduce illegal coca production.33 Finally, in January 1977, the US embassy mentioned for the first time the existence of a draft of a new anti-narcotics law.34 In April of the same year, a group of four ministers gave a first approval to the draft. However, it took Peru’s cabinet, the Council of Ministers, until February 1978 to sign the reform, amid “passive and active resistance in a number of Peruvian circles,” according to the US embassy.35 In the meantime, PIP officials, the minister of health, the attorney general and the inspector general expressed their support for the law to the US embassy.36 Furthermore, the embassy evaluated the Ministry of the Interior, which oversaw the work of PIP and the GC, as instrumental in the drafting of the new law.37

After the law was passed, the United States established project agreements with PIP and the GC. Further agreements were signed with the Peruvian government (to curb coca plantations and aid agriculture) and the Ministry of Education.38 By September 31, 1981, the United States had spent US$ 3,672,000 in assisting Peru’s narcotics control program. From this budget, PIP (US$ 1,001,000) and GC (US$ 741,000) were the biggest recipients. Although the financial support was small in comparison to the sums provided in future decades, it was higher than Peru’s total drug control budget for the same time (US$ 3,100,000).39 Thus, the financial support helps explain why the Ministry of the Interior and its associated actors were so keen on passing the new law.

Final thoughts

The above analysis of Peru’s Decree Law 22095 of 1978 is relevant to the argument of this article not only because it provides a practical example of how to apply the PPF but also because it provides strong evidence in favor of the claim that political incentives-i.e., considerations about power, material benefits, standing, and prestige-are the main drivers of drug policy reforms. Put differently, how Peru’s decision makers thought about coca cultivation and drug use has mattered far less than the incentives from the international and, to an even greater extent, the national context. The analyzed communication from the US embassy strongly suggests that the reform would not have been possible without the support of key domestic players, including the Ministry of the Interior and its associated actors, all of which benefitted from US aid. This is an important finding as it shows that bilateral pressure alone could not do the job. In this sense, the argument presented here does not seek to deny the importance of US influence but to provide a detailed analysis of how it achieved its objectives while highlighting the importance and agency of local actors in the fomenting of prohibitionist drug laws. To this end, the United States needed to cultivate close alliances over an extended timeframe. On the one hand, these partners were eager to support drug prohibition and coca eradication in return for the material benefits promised by the United States. On the other, the analysis also indicates that dominant discourses and ideas about drug use and coca, rather than being imposed, connected well with Peruvian actors. Future research should pay close attention to these bilateral, multilateral, and transnational linkages to provide more sound explanations of past and present drug policy choices and trends. The present article hopes to have offered a coherent framework and research strategy to carry out systematic and theory-guided research in this evolving policy field.