Introduction

The emergence of regionalism in the post-Cold War period marks the leading role played by regions in international relations and International Studies. In South America, this trend became more evident with the deepening of regional unipolarity, the consolidation of Brazil as an emergent power in world politics, and the articulation and strengthening of new cooperation and integration initiatives in the 2000s. This context produced incentives for the development of studies focused on the role of Brazil as a regional power (Burges 2008; 2015; Fuccille et al. 2017; Lapp 2012; Lima and Hirst 2006; Malamud 2011; Malamud and Rodriguez 2013; Merke 2015; Mesquita 2016; Schenoni 2012; Spektor 2010; 2018; Varas 2008; Vitelli 2015). A large part of these studies has prioritized as main variables of analysis elements at the unit level, such as foreign policy and the interactions among regional actors. Because of that focus, the periodization of these analyses was limited to more recent periods. Despite the development of the field and advances made by such studies, some gaps remain. We underline here the inexistent or minimalistic definition of regional systemic structures and, consequently, the scarcity of macro-historical perspectives, necessary to understand both theoretical issues-like structural changes and their meanings for regional dynamics, and more empirical concerns-such as the ascension and role played by regional powers.

Such gaps indicate a limited engagement of the literature on New Regionalism in South America with the development of important discussions within International Relations theory and New Regionalism, such as deeper theoretical perspectives on the complex and dynamic characteristics of interstate systems (Buzan et al. 1993; Harrison 2006; Jervis 1998). Bearing on advances provided by developments in other disciplines, such as Systems Theory (Capra 2002; Capra and Luisi 2014; Morin 1990) and Historical Sociology (Mahoney 2000; 2006; Skocpol 1984), these new perspectives call for a more robust comprehension of the process of macro-historical changes (Holsti 1996b). Similarly, they invite a deeper analysis of the phenomenon of structuration even at the level of deep structures (Buzan et al. 1993; Buzan 1998) and the merits of systems comparisons in time and space (Buzan and Little 2000; Hettne et al. 2000). Nonetheless, few studies about the South America region and the leading position of Brazil consider the possible explanatory horizons provided by this literature.

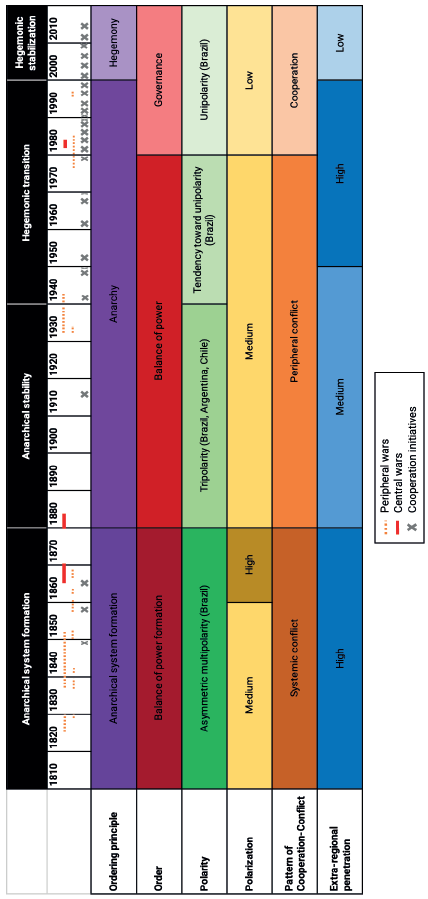

Considering these issues, this study aims to evaluate the systemic and macro-historical significance of Brazil’s predominant role in the region. To address these gaps, we argue that the prominence assumed by Brazil during the 2000s-2010s, in addition to interpretations about its foreign policy and other domestic and interactional determinants, should be understood as part of macro-historical transformations related to the structural formation of the South American regional system. We claim that the prominent role assumed by Brazil in the recent period means, more deeply, changes in the structure of the regional system, and particularly, an outcome of a tendency towards a classical hegemonic structural type in the region. In the South American regional system, this structural type consists of a combination of (i) unipolarity, (ii) a regional governance order, and (iii) a hegemonic ordering principle. We identify four periods of regional structural transformation: 1) anarchical system formation (1810-1870s); 2) anarchical stability (1880-1930s); 3) hegemonic transition (1940-2000s); and 4) hegemonic stabilization (2000-2010s).

We also identify that such changes are part of major macro-historical transformations instigated by ruptures produced by regional central wars. In the case of South America, the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870), the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) and the Malvinas/Falklands War (1982) stand out as three regional central wars that instigated the main structural changes. Such structural changes in the regional distribution of power, order, and ordering principle also relate to interactional aspects, such as 1) extra-regional penetration and 2) consolidation of alliances/rivalries between the units (polarization). Adopting process tracing and historical comparative methods, the article observes and describes the causal chain of such historical changes.

The work is divided into three sections besides this introduction and the conclusion. First, we evaluate the research agenda in which this work is placed, discussing the contributions, challenges, and gaps of the New Regionalism approach regarding the South American case, and interpretations about Brazil’s recent prominence in the region. We subsequently present a systemic and macro-historical analytical framework to study structural changes in regional systems. The second section of the paper applies our theoretical framework to our empirical study, which consists of a macro-historical analysis of the formation of the South American regional system since the post-independence period (1810-2010). Finally, the third section evaluates the causal variables that led to structural changes in the region and explains the historical and systemic significance of Brazil’s recent regional position, identifying the patterns of regional structural transformation. We conclude by discussing the main findings and challenges of the study.

New Regionalism and South America: Main gaps and theoretical contributions

Studies on regions gained prominence in the literature on International Relations in the post-Cold War period, both in their empirical and theoretical dimensions. Empirically, the organization of an agenda dedicated to the study of regions allowed the discipline to bring attention to territories and actors previously marginalized in the scientific and theoretical production on International Relations, including particularities of the regional systems in the Third World (Kelly 2007; Acharya 2007; Ayoob 1999; Castellano 2017). Theoretically, studies on regions began to be reorganized in the discipline as a specific research tradition on the path to consolidation (Hurrell 1995; Fawcett 2004; Kelly 2007; Fawn 2009; Nolte 2011). In this second realm, New Regionalism (NR) stands out by advancing a theoretical approach in which regions are considered relatively autonomous systems (Buzan and Wæver 2003; Buzan and Little 2000), with particular structures and complexity, shaped by specific social and political aspects (Katzenstein 2005) and by the degree of interaction between units (Hurrell 1995).

Studies on New Regionalism in South America have also flourished following the new cycle of regional cooperation and integration initiatives during the 1990s. New approaches gained visibility, mostly focusing on the interactional aspects of the region (Malamud 2011; Lapp 2012; Flemes and Wehner 2015; Wehner 2015; Merke 2015), regional processes, initiatives of integration, and their institutions (Oelsner 2005; Gardini 2010; 2015; Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012; Rivarola Puntigliano and Briceño-Ruiz 2013; Lima 2013; Briceño-Ruiz and Ribeiro Hoffmann 2015; Riggirozzi and Grugel 2015; Quiliconi and Salgado Espinoza 2017), and the role of foreign policy and leadership of regional powers, especially Brazil (Lima and Hirst 2006; Varas 2008; Burges 2008; 2015; Spektor 2010; Schenoni 2012; Lima 2013; Rodriguez 2012; Malamud and Rodriguez 2013; Vitelli 2015; Fuccille et al. 2017). However, gaps remain, and despite the progress made, studies on South American regionalism are still incipient when it comes to incorporating some advances and theoretical propositions of New Regionalism theory.

Firstly, the literature on the region denotes a lack of definition regarding the systemic structure of South America. Even when they observe more than just regional interaction aspects, regional studies on South America often simplify the concept of regional systemic structure. Even when authors do discuss systemic elements, structural analysis is usually restricted to studying the regional distribution of power (Schenoni 2012, 2018; Rezende 2016),1 or focused on a systemic, extra-regional point of view (Mijares 2020). Secondly, a regional structural element-the regional order-is often mistaken as a synonym or a mere reflection of polarity (Buzan and Wæver 2003; Schenoni 2012), and other times, as an equivalent of what would be, in fact, the systemic ordering principle (Burges 2008, 2015). This last problem is related to a more general issue in the discipline regarding the lack of definition or invariance of the ordering principle, since most of the literature only accepts the premise that ordering structures are static and only considered at the global analytical level.

The second issue with assimilating the deeper advances of New Regionalism is the so-called “present bias” (Briceño-Ruiz 2013, 3-4 and Rivarola Puntigliano) in part of this literature, resulting in scarcity of macro-historical perspectives in the literature of South American regional studies. Most works have focused strictly on the analysis of recent periods, mainly after the 1980s. While a contemporary focus provides detailed studies on contemporaneous issues, such an approach tends to prioritize regional interactions and aspects of the units, to the detriment of structural variables.2 Therefore, the lack of a macro-historical analysis informed by structuration processes overshadows structural systemic changes, due to the higher stability of systemic structures vis-à-vis other systemic levels. In short, by failing to address structural complexity and macro-historical changes, New Regionalism in South America have extracted the object from this approach, but not its theoretical potential. We argue for the need to reinvigorate regional studies in South America by incorporating the theoretical advances made by the New Regionalism approach and broader auxiliary theories, which may improve New Regionalism itself.

Systemic complexity and macro-historical changes

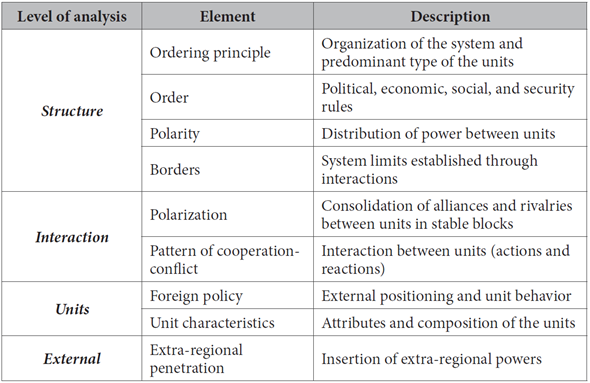

To promote studies about the structure level within regions, it is necessary to discuss the composition of regional systems. Theories of complex systems are open to the relation and transformation of different elements and levels of analysis in a system, including regional ones. Systems analysis in International Relations have adopted the general division of complex systems in structure, interaction, and unit levels (Buzan et al. 1993; Buzan and Little 2000; Buzan and Wæver 2003). Regional systems are also characterized by openness so that the type and level of external (global) penetration matters. Based on such theoretical foundations, we follow Castellano’s (2017) model of regional analysis, which, using the regional system literature, organizes systems in four levels of analysis. Table 1 summarizes the elements of the model. In addition to complex systemic thinking, the analytical model helps overcome the problem of the absence of connections between different levels of analysis and systemic elements. Moreover, it allows for progress concerning the problem of how to evaluate structures in regions and unravel the temporal limitation predominant in the literature. By interpreting regions as complex open systems, we can analyze aspects of both their formation and the transformations they undergo through broad historical periods, making possible a macro-historical approach that helps analyze the structural formation and change of systems.

Table 1. Agent-structure interaction in regional systems: Levels of analysis

Source: Own elaboration.

Moreover, our theoretical framework encompasses a discussion of macro-historical continuity and change in systemic elements based on the structuration process and types of changes, following Historical Sociology conceptions of evaluating macro-historical changes in social, economic, and political units and structures through the analysis of structuration processes (Skocpol 1984; Mahoney 2000; 2006), as proposed by Ruggie (1983; 1989), Wendt (1987), and Buzan et al. (1993). Therefore, the main contribution of Historical Sociology considered here is the use of comparative-historical methods to identify causal chains, mechanisms, and critical junctures (Mahoney 2000; Tilly 2001). But it is also important to consider that one of those causal mechanisms that produces macro-historical changes in international systems, according to this approach, is the process of war, which may impact both the formation and transformation of units (Tilly 1975; 1990) and structures (Gilpin 1981), constituting a critical juncture to the trajectories of change. This relation will also be observed in the case of the South American regional system.

Relationship between systemic elements: Identifying structural types

A theory of systemic structure types allows for reducing ambiguity about the elements of the structure and deep structure of a regional system and their possible relations and variations. This involves two main tasks. First, we need a clearer idea of possible variations in the structure other than polarity, which has been the principal element of study in structural theories. When we talk about structure, we are not only referring to the distribution of power but also to the systemic order and ordering principle of systems. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish these elements properly. Order is a structural element of international and regional systems, defined here as a set of attributes, rules, and political, economic, socio-ideological, and security norms of the system, established as formal or informal institutions, that constrain the actions of the actors.3 Thus, our definition follows both the structural and institutional traditions, considering their variation through degrees of institutionalization, a process by which institutions acquire value and stability (Huntington 2006, 12). Concerning the ordering principle, we reproduce the idea of Buzan et al. (1993) about the existence of variations in the elements of the deep structure.4 Following Watson (1992), we consider hegemony as a variation in the ordering principle, situated between hierarchal and anarchical deep structures.5 Hegemony, therefore, would not only be an ideal configuration between power distribution and convergence of interests in the system,6 but also a reflection of the consequences of such distribution on the stability and acceptability of regional orders. Therefore, we consider hegemony as a hybrid configuration of the ordering principle, in which the impacts of anarchy on systems are reduced, meaning that alternative forms of organization of the system’s structural foundations are possible.

Our second task is to propose a model to categorize these structural types, identifying possible connections between the distribution of power, systemic order, and ordering principle, which may denote moments of stability, crisis, or transition in these systems. Regarding polarity, different configurations may coexist in the same formations of order and ordering principle, and vice-versa. Then, the systemic order and the ordering principle are not dependent on the distribution of power; in other words, different structural types can be formed either under unipolarity, bipolarity, or multipolarity. Regarding the connection between systemic order and ordering principle, the degree of institutionalization may reflect the hierarchy level of the system through structuration processes. Thus, the structuration of the systemic order indicates more deeply the temporal-spatial dimensions of the institutionalization process. Therefore, the institutionalization of systemic order directly affects the characteristics of the ordering principle with a long-scale process of structuration. For instance, anarchic systems are characterized by balance of power orders, while hierarchical systems usually result from government orders. On the other hand, hegemonic structures-individual or collective-follow from governance orders.

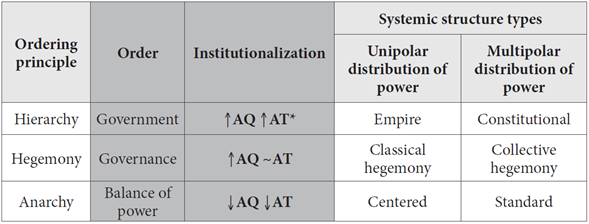

In the case of balance of power orders, the types of systemic structure could assume two different characteristics: centered, in a situation of unipolarity, and standard, in the face of multipolarity.7 This type of order is fundamentally related to the anarchic characteristic of the systemic order, in which the relationship between states is sparse and not formalized. Governance orders present medium to high levels of acquiescence and moderate levels of authority. They encompass formal and informal institutions through which the system is governed, and for which the satisfaction of its collective needs is sought (Rosenau and Czempiel 1992), but there is no capacity to impose decisions on all units in a homogeneous way and the governing group is distinct of the institutions established. In a situation of hegemony and governance, the systemic structure may manifest itself as a classical hegemony (in unipolarity) or a collective hegemony (in multipolarity) (Clark 2011; Simpson 2004; Watson 2006;). A government order promotes hierarchy of high authority, creating a situation of subordination. Ideally, it could manifest itself as an empire, in a situation of unipolarity, or as a constitutional systemic structure, in a situation of multipolarity (Clark 2011; Ikenberry 2001; Watson 1992). A constitutional systemic structure, in turn, would be organized in institutions and policies with a high degree of authority, specifying rules, and limits in relation to behavior and the exercise of power, but shared between the main powers or through a formal institution holding this authority.8 Table 2 summarizes our model and the relations described, combining the structural elements of the system to identify possible systemic structural types.

The structuration of the South American regional system: Continuities and changes since the independence period

The formation of the South American regional system began with the processes of independence of national states, which extended from the 1810s to 1825. This process gradually transformed the colonial states into independent nations, denoting a change in the structural foundation of the regional system related to the functional differentiation of the units and the systemic ordering principle. In general, we can identify the decades between 1810 and 1870 as the period of formation of the regional anarchic system. During this interval, the absence of a consolidated regional order marked a phase characterized by high levels of systemic conflict, given the challenges to consolidate the states and their territorial and border definitions through which they sought to build a systemic status quo favorable to their ambitions (Centeno 2002; Holsti 1996b; Kacowicz 1998; Mares 2001).

Following the processes of independence, the consolidation of national states led to several outbreaks of domestic conflicts and regionalized disputes that turned into inter-state wars. From 1825 to the 1970s, regional rivalries began to take shape because of disagreements over power resources and territorial issues, manifested mainly through border disputes (Centeno 2002; Kacowicz 1998; Mares 2001). Because of that, we can identify a medium level of polarization in this period. Despite the coexistence of alliances and rivalries even escalating to the degree of armed conflict, cohesive and/or openly declared coalitions were not formed for any purpose. Nevertheless, in the brief interval of regional central wars,9 considering the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870) and the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), we identify a period of high polarization with cohesive and declared blocks of interstate rivalry.

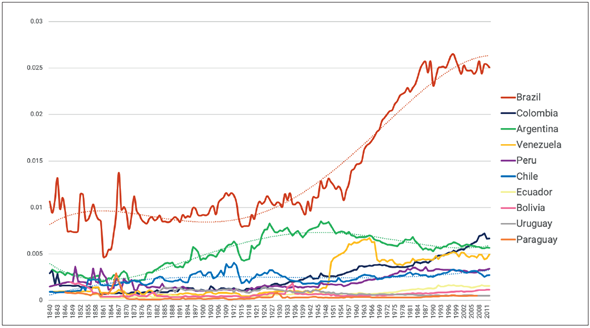

Regarding the distribution of power, its configuration until the 1880s was somewhat imprecise. Figure 1 illustrates the material capabilities of South American countries based on the Composite Index of National Capabilities (CINC).10 These data evidence a multipolar distribution of power in this period, with a high degree of asymmetry between regional powers. The preponderance of Brazil stands out, but it is not highly distinguishable since the gap among Argentina, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile is small. A definition in polarity can be observed from the 1880s onwards, after the regional central wars. In the transition period between the 1860s and 1880s, Brazil had a relative decline, as illustrated by the trend line in Figure 1. The same period shows the growth of Argentina (from the 1870s) and Chile (from the 1880s). Brazil resumed growth from the 1890s onwards, and until the 1930s, a regional tripolarity can be seen around Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.

Source: Own elaboration, based on data from the Correlates of War (COW) Project (2017).

Figure 1. South America: Material capabilities, CINC, 1840-2010

With the definition of the distribution of power, a cooperative turn in regional relations can be identified until the mid-1950s, characterizing what some authors designate as a South American concert (Kacowicz 1998; Merke 2015). In this second period of regional system structuration, few conflicts escalated into interstate wars because of the balance of power and deterrence behavior created after the systemic wars (Holsti 1996a; Schweller 2006).11 This conformation between regional powers led to a reduction of systemic conflict, also provoking a change in the pattern of cooperation-conflict, which, in turn, influenced the characteristics of the regional order under consolidation. Nevertheless, local and peripheral wars, such as the Chaco War (1932-1935) between Bolivia and Paraguay and the Zarumilla War (1941) between Peru and Ecuador, manifested the dissatisfaction and discontent of secondary powers regarding the established order. In addition, inter-state conflicts, such as the Letícia Conflict (1932) and the Beagle Channel crisis (1979), although not escalating to the level of war, were important outbreaks of conflict and systemic polarization. Nevertheless, at the center of the system, cooperative behavior prevailed in regional powers relations, while remaining rivalries were manifest too. Therefore, despite significant changes, we can identify a medium level of polarization in this second period.

This accommodation of power and polarization gave rise to a recurrent behavior that consolidated a balance of power order in the region, characterized by low levels of institutionalization both in terms of acquiescence and authority. The articulated order guaranteed the system’s stability by maintaining the conflict between secondary powers, with regional powers acting timidly in the mediation and arbitration processes. The existence of latent dissatisfactions and a more autonomous behavior of states-little committed to the values and norms of the order-are characteristic of this type of order. Based on principles such as the defense of sovereignty, self-determination, nonintervention, and peaceful settlement of disputes (Holsti 1996a; Kacowicz 1998), the order in this period became progressively more institutionalized.

At the economic level, there was a process of transition from primary-exporting economies to more diversified national economies. A regional trade perspective was strengthened with the creation of organizations, such as the Latin American Free Trade Association (1960) and the Latin American Common Market (1967). In the security pillar, a perceived national security prevailed initially, but, from the 1940s onwards, a change to a hemispheric security perspective is manifest in regional instruments, such as the Inter-American Defense Board (1942), the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (1947), and the Organization of American States (OAS) (1948). The period from World War II to the end of the Cold War is marked by the expansion of extra-regional penetration in the region, especially due to a strong influence of the United States in regional dynamics and the limited agency of regional players against extra-regional powers (Mares 2001, 32).

In addition, aspects of the units of the system and domestic variables-although not investigated in this study-also appear to be relevant explanatory variables for understanding some of these changes (Rodriguez 2012; Vedovato and Castellano 2019). To some extent, the two aspects are also related since some changes at the level of the units are consequences of the extra-regional dynamics of the period. Similarly, events such as the United Kingdom’s armed intervention during the Malvinas/Falklands War (1982) are manifestations of a high level of extra-regional penetration in the region. In this context, the trend toward a unipolar regional system-which began in the 1950s around Brazil-was consolidated in the 1980s when the decline of Argentina was settled as an outcome of the Malvinas War (Schenoni 2018). Following the war, Figure 1 shows the interruption of the recovery of capabilities, observed in the late 1970s, as well as Argentine’s failed chance to recover after that, given that its capabilities remain low compared to previous periods. Thus, the post-Cold War external context, plus the occurrence of the Malvinas War, can be understood as additional elements leading to a change in the systemic structural configuration in the region.

After the 1980s, a decrease in the levels of the regional conflict started to characterize a new regional behavior pattern, with the predominance of systemic cooperation. Except for the Cenepa War (1995) between Peru and Bolivia and other low-intensity conflicts, the advance of cooperative projects was significant, mainly through agreements and initiatives of regional integration. This context gave rise to a broader pattern of regional alliances, with most South American countries joining stable associations through dialogue blocks and cooperation organizations. These aspects are part of the governance regional order formation, with higher acquiescence and a moderate to higher level of authority. Historical dissatisfactions of secondary powers began to settle, with a growing satisfaction around the systemic status quo and commitment to regional institutions.

The 2000s marked a critical reaction to neoliberalism and the influence of extra-regional powers in the region (Garzón Pereira 2014; Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012), moment when the order started to centralize in Brazil’s role as a preponderant regional power. The South American Community of Nations (2004), later the South American Union of Nations (UNASUR) (2008), emerged as an openly regional governance instrument. CELAC (2010) was also a result of the Brazilian initiative to expand its sphere of influence and deepen the process of regional integration (Lima 2013). These new regional configurations, together, characterize a change in the regional order, which gradually assumed a tendency toward a governance order since the acquiescence of the new order grew significantly compared to the previous period, and a certain authority came to be sustained by the strengthening of regional institutions. The conformation of this order led to increased systemic cooperation, producing a new change in the pattern of cooperation-conflict. Positive feedback was established between this new cooperation-conflict pattern and the regional order, characterizing the emergence of the governance regional order.

It is necessary to highlight the role of extra-regional penetration in this process. In this work, we aggregate (global) systemic processes to the interactional dynamics. For the period analyzed, we have to consider that in most of the structuration process, South America had been under the hegemony of the United States. Transition period outcomes seem to be determinant for the configuration observed. In the transition between UK and US hegemony, states that better accommodated to the US emergence had positive gains in the hierarchy of power. Then, during the Cold War, the limits of regional autonomy strengthened with the growing influence of the US, not without consequences for the regional dynamics. Currently, the influence established by the US has been considerably tackled by the rise of multipolarity movements and emerging actors (especially China). The global systemic reconfiguration and the dynamics of power transition may be central to understanding the future of the regional structure. The emergence of China in the last decades is critical in this regard (Cui and Pérez García 2016; Ellis 2014; Gallagher 2016; Vadell 2019). However, it is still imprecise how this can (or will) affect the regional structure and regional order dynamics in South America or whether the degree of extra-regional penetration will grow. Undoubtedly, China’s emergence has a growing effect on the interaction process, challenging the limits and dynamics of regional autonomy and the possibilities of agency for regional players against extra-regional powers. However, considering the long-term structural perspective we adopt here, it is still impossible to account for lasting effects and know what outcomes will derive from this process. What can be lined out, however, is that processes impact structure in the long term and that current dynamics may be critical to understanding structural changes in the future. For instance, it should be further explored how (global) systemic structural change interacts with structures in regional systems. Is this process interplayed, or does it occur at different times? Future works should examine more directly the relationship between these two variables.

In summary, based on this macro-historical approach, it was possible to glimpse four periods that characterize the moments of continuity and change in the regional system during the post-independence period. The initial period-the formation of the regional anarchic system-was a period of change from the 1810s (the beginning of the independence processes) until the 1870s, with regional central wars. In a second moment, a period of stability followed, with the consolidation of a regional balance of power order, from the late 1880s to the 1930s, when a new period of change started from the 1940s to the 2000s. Finally, a fourth moment signaled the trend of a hegemonic transition, in which a new systemic configuration indicated the articulation of a governance regional order, a scenario where Brazil emerged as the leading regional power. Figure 2 illustrates the synthesis of our macro-historical periodization and brings together the systemic elements analyzed at the structural, interactional, and external levels of the regional system, highlighting the periods of continuity and change.

Causal process and patterns of structural change: The case of South America

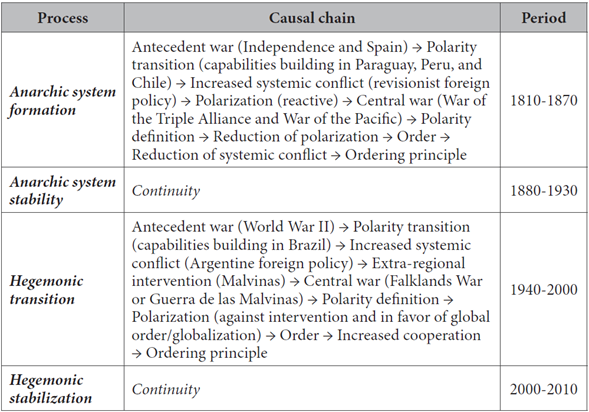

Based on the proposed periodization, changes in the structure of the regional system (polarity, order, and ordering principle) are intertwined with broad historical causes and processes. To identify the causal conditions for the observed changes in the regional systemic structure, we outline a causal chain of these processes using process tracing (Mahoney 2015). As noted, the first period corresponds to the formation of the regional anarchic system (1810-1870). The systemic structural change can be understood as a result of the independence processes and wars of consolidation among states, which constitute antecedent conditions12 for the formation of the South American regional system. Table 3 illustrates the synthesis of the causal processes described in the previous section, identified in two moments of change in the regional structure of South America: the formation of the anarchic system (from the 1810s to the 1870s) and hegemonic transition (from the 1940s to the 2000s).

Table 3. Causal process of changes in the systemic structure of South America

Source: Own elaboration, based on Schweller’s model (2006).

With the identification of the causal process leading to changes in the regional structure, it is possible to observe the existence of a common causal pattern in the historical periods analyzed. During the periods of change, the initial condition is an antecedent war. In the first case, the wars of independence, conflicts against extra-regional actors, and internal conflicts appear in the causal chain as trigger events in the structuration process. In the second moment, World War II seems to play a similar role, although external wars are beyond the scope of this article. As already discussed, the most direct impact was on regional polarity, causing changes in the distribution of power in the regional system. In the first case, it led to a relative increase in the capabilities of Chile, Paraguay, and Peru. On the other hand, the internal conflicts in Brazil and Argentina seem to have had a negative influence on their capabilities in this initial period, since they presented oscillations and a tendency toward decline between the decades of 1840 and 1870 (see Figure 1). In the second moment, the external war seems to anticipate an increase in the capabilities of Brazil.

Transitions in polarity have affected the interactional aspects of the system, polarization, and extra-regional penetration (derived from foreign policy options of actors), leading to regional central wars. In the first case, the combination of a new polarization and the revisionist behavior of belligerent states led to the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870) and the War of the Pacific (1879-1883). In the second case, the interactional factor that impacted the outcome was the combination of Argentina’s foreign policy orientation and British extra-regional intervention, leading to the Malvinas/Falklands War (1982). After the regional central wars, in both cases, systemic polarity was defined according to the outcomes of these wars. In the first case, the War of the Triple Alliance allowed maintaining Brazil’s position and the rise of Argentina as a regional power, and the War of the Pacific led to the strengthening of Chile. In the second period, the Falklands/Malvinas War contributed to the decline of Argentina and the consolidation of Brazilian unipolarity. In both cases, these changes settled systemic polarization, reduced the pattern of rivalries, and led to changes in the regional order. The new order, shaped by the units favored in the distribution of power, impacted the configuration of the pattern of cooperation-conflict, reducing the levels of systemic conflict. This relationship, in turn, is co-constituted since the reduction of the systemic conflict also allowed creating a new basis of interactions in the regional order. Figure 3 illustrates the observed pattern of changes.

Source: Own elaboration.

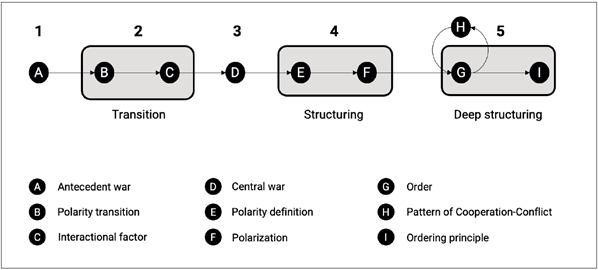

Figure 3. Pattern in the causal process of changes in the systemic structure of South America

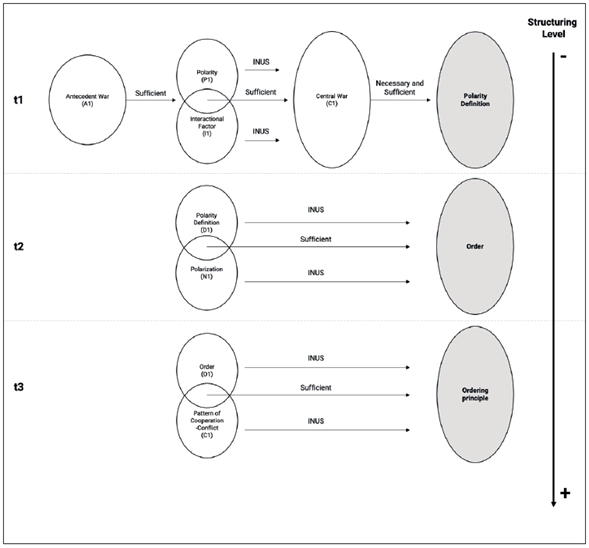

The results also allow us to evaluate the sufficiency and necessity conditions of the observed variables. We argue that the antecedent wars were sufficient conditions for polarity variation and changes in interactional factors. Nevertheless, these changes in polarity and the influence of interactional factors, nonetheless, seem to be INUS conditions13 for structural change. Because these conditions can lead to a non-violent or a violent type of change, together, they are a sufficient condition for the central war to occur. Otherwise, the regional central wars, individually, are both necessary and sufficient conditions for polarity definition.14 Moreover, polarity definition and polarization are both INUS causes for the order change. Order structuring and the stabilization of the pattern of cooperation-conflict also act as INUS causes, indicating the possibility of a change in the ordering principle. Therefore, the transformation of regional systemic structures seems to be conditioned by a complex configuration of variables and causal processes. Figure 4 analyzes these relations.

Organizing the variables in set diagrams helps create generalizations and trace different temporal levels in the structuring process analyzed. We isolate these variables to observe how they would behave in different trajectories and structuring timings. Figure 4 illustrates three different times in the broad process of structural change: (t1) polarity definition, (t2) order change, and (t3) ordering principle change. We emphasize the differences between these processes regarding the temporal-spatial dimensions of institutionalization: the more structural the elements, that is, the more stable they are, the more relevant becomes the role of the temporal dimension in the consolidation of those changes. Therefore, the interaction between the regional order and the stabilization of the cooperation-conflict pattern becomes essential to understand the process of deep structuring since this deeper process would be necessary, over time, to enable an alteration in the ordering principle. Based on this interaction, three different paths are possible: i) if the order accommodates the cooperation-conflict level for a long time, this set alters the ordering principle; (ii) if this interaction fails and turns into a systemic conflict, this can lead to a new central war; or (iii) if the order fails with peripheral conflicts or even with cooperation, a new process of change can develop, establishing a new polarization, generally articulated from states dissatisfied with the status quo.

Source: Own elaboration, based on Mahoney and Vanderpoel (2015).

Figure 4. Set diagrams and the causal process of regional structural transformation

Regarding the other dimension of our argument that implies a relationship between the role played by Brazil in South America and changes in the systemic structure of the region, it is also possible to establish a causal relation. By tracing the causal chain and generalizing the variables, we can notice that the leading role assumed by Brazil in the past years, more than a foreign policy behavior, was permitted by the specific structural configuration that emerged as an outcome of these processes of regional formation. Our findings suggest that deep structural change depends on the combination of two independent factors: a process that leads to a polarity definition (the settlement of the distribution of power) and a deep structuring process, causing changes in the regional order and, eventually, in the ordering principle. As we saw, Brazil’s status as the main regional pole (in terms of material capabilities) was conditioned, cumulatively, as an outcome of the long-term process of regional system formation, resulting, ultimately, from a regional central war (Malvinas/Falklands War) and the new regional polarity defined after that (Schenoni 2018). Furthermore, changes in polarization and the position as a unipolar actor-the status as a leading power-and its engagement in a governance regional order are also set by the long-term process of structural configuration, which reaffirms the structural meaning of Brazil’s prominence in the region.

Conclusion

This article sought to contribute to the debate about South American regionalism and Brazil’s regional position, by bridging International Relations theory and New Regionalism through a study on the formation of the South American regional system. Based on a systemic perspective and a long-term historical analysis, we identified the historical relationship between structural and interactional changes in the regional system. Departing from a theoretical proposal to identify systemic structure types through the combination of different structural elements, we concluded that Brazil’s regional position is an outcome of a macro-historical process of regional formation, the combination of both systemic conditions (structure) and foreign policy behavior (agency). This configuration results from structural changes in the regional system, such as the aim to build a governance regional order and conditions for a hegemonic ordering principle. Moreover, from a macro-historical perspective, and using process tracing to test our claims, we found that the conditioning factors and characteristics of structural changes throughout history are fundamental to understanding the current configuration of the regional system.

The study contributed specifically to better understanding the position occupied by Brazil in the region in the last decades, which allowed identifying elements of hegemony in the systemic structure since the 2000s, in line with what was proposed by previous studies (Burges 2008; 2015; Lapp 2012; Mesquita 2016 Poggio Teixeira 2014). What we observed from the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s is a deepening hegemonic stability based on the pillars of high acquiescence and moderate authority around the established order. Brazil’s coordinating role in the articulation of UNASUR and the institutional expansion of MERCOSUR, as well as its leadership in the cooperation processes in security and defense, confirm the acquiescence of other actors in relation to the established order in this period. However, it also reflects positively on the relationship patterns among the states of the region and on the characteristics of the regional institutional architecture. This is different than saying that Brazilian leadership is fully accepted by the other countries, as argued by critics of Brazil’s role as a regional leader (Malamud 2011; Spektor 2010). In fact, as Lima (2013) argues, acquiescence is both easy to distort and difficult to operationalize.

More generally, our study recovers the theoretical contributions of New Regionalism in evaluating the complex and dynamic character of international systems and their multilevel transformations in different periods, scopes, and depths. We apply these contributions in our theoretical model by integrating structural types and evaluating their change in relation to co-constitutional interactional aspects, which includes the role assumed by systemic wars as a trigger for both transformation/instability and continuity/stability. We also advance toward a more comprehensive qualitative historical analysis of the causal chains of a complex systemic process. By applying these theoretical innovations to a regional system of the Global South, in line with past efforts (Ayoob 1999; Acharya 2007; Buzan 1998), we contribute to connecting Third World regions to the theoretical thinking of International Relations. Although this gap has been reduced by Regionalism studies, these regions are still recurrently ignored by mainstream International Relations theory or treated with theoretical insulation, which emphasizes their exclusivity over traditional cases (Cervo 2008).

Nonetheless, many challenges are still present. Firstly, to fully investigate the levels of regional order acquiescence, it is less important to verify the performance or acceptance of Brazil as a regional leader than to evaluate the results, responses, and agency of secondary powers in the established order. Progress in cooperation under unipolarity does not make less relevant the role played by secondary powers. This is to say that regional order does not depend solely on the behavior of regional powers. In the case of South America, this would convey that the future of the regional order is less dependent on Brazil’s position and more on the stance and agency of other countries vis-à-vis the regional order. As already observed by Castellano (2017), the performance and behavior of secondary powers are crucial to understanding regional order configurations. This stands out in the dimension of both acquiescence and autonomy.

Regarding the tendency toward a hegemonic ordering principle, a more profound investigation of hegemony in peripheral regions should be carried out by future studies. We believe that it is imperative to consider the existence of additional challenges for unipolarity to translate into hegemony in peripheral regions. This is because interactional factors and the unipolar configuration are constrained by more robust disputes about the consolidation of state capabilities in the case of regional powers. Regional hegemony is hard to afford, especially in the long run, because external policies capable of ensuring regional acquiescence are challenged by limited state capabilities. Therefore, the existence of a structural condition favorable to hegemony, as pointed out in this study, does not necessarily translate into hegemony. To build a hegemonic order, it is necessary to adopt strategic and sustainable state policies over the long term, reason why we argue that Brazil lost the opportunity to embrace its position as a regional hegemon. Still, according to our theoretical model, the existing conditions for hegemony could translate both into a classic (unipolarity) and a collective hegemony (multipolarity). This is to say that regional actors could collectively participate in the re-configuration of the system through governance alternatives, such as regional institutions.

Finally, it should also be considered that the porosity of regional systems and the long-lasting dependence on extra-regional powers seem to be determining factors that prevent deeper structural changes and governance alternatives in the region. Peripheral regions with low systemic competition at the interregional level produce few incentives for regional powers to evaluate their needs, reform their external policies, and create effective governance structures (Malamud and Alcañiz 2017) and more accepted orders and stable systems. Despite these challenges and the recent decline of Brazil in regional policy, the structural configuration of the South American regional system is, therefore, a determinant for understanding the past and the future of regional dynamics.