Introduction

During the 1980s and early 1990s, most Latin American countries undertook a series of reforms seeking to transform their state apparatus. Following the recommendations of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, these reforms focused on the prioritization of public spending, fiscal discipline, economic liberalization, and privatization. This set of measures that concentrated on purely economic aspects became known as first-generation reforms.

In the 1990s, multilateral organizations reviewed their proposal to diminish the size of the state, arguing that state intervention in the economy was not only justifiable to reduce failures associated with the free functioning of markets but also necessary to decrease social inequalities brought about by the first generation of reforms. The changes in public administration sought to raise the quality of state management by creating public organizations that would help reduce the uncertainty inherent in markets and strengthen institutions. This new group of changes became known as second-generation reforms.

Since the 2000s, a new process of reconfiguring state functions has taken place. The state retains its presence in economic life but considering the circumstances and characteristics of each country. This process emphasizes the need to improve the public sector, not only by modernizing it from a technological point of view but also by optimizing its procedures and practices to make it more responsive to citizens’ needs. This new wave of reforms seeks to rationalize the organization and operation of public administration to achieve greater social effectiveness in using public resources.

These three drivers of change in the structure of the public sector involved the creation, modification, and termination of public organizations. The reorganization of the State has been a constant activity of politicians throughout the region. On the one hand, defining the structure of the administration enables the establishment of the organizations, competencies, and public resources available to a government to conduct its political project. However, on the other hand, the possibility of reforming the structure of public administration also opens the chance for politicians to deliberately eliminate public organizations for ideological or electoral reasons (Kuipers, Yesilkagit, and Carroll 2018) . The following three examples from Colombia illustrate this reality.

First, during the administration of President César Gaviria (1990-1994), the Ministry of Environment was created by Law 99 of 1993. In 2002, during the first government of President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2006), it was merged with the Ministry of Housing. In 2011, with the first state reform of President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018), these two entities were separated again.

Something similar happened with the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Interior. In 2003, through Law 790 of 2002, President Uribe gave way to the merger of these two institutions. Subsequently, in August of 2011, President Santos signed Decree 2897, through which they, once again, became two separate ministries.

Second, between 1958 and 2018, presidents who moved into the Casa de Nariño undertook 389 transformations that affected the size of the Executive Office of the President. Thirteen percent of these changes corresponded to the suppression of units created by former presidents, while 65% were modifications made to the structure and functions of existing entities.

Third, during the congressional discussion of the Budget Law for the year 2020, the Representative to the House, and vice-president of the Conservative Party, Wadith Manzur, proposed the elimination of several state entities created during the government of former President Juan Manuel Santos (2014-2018). He argued that the operating expenses of these entities were exaggerated, and that this money could be used instead for social investment. The Conservative Party, to which the Representative belonged, was a member of the coalition of the government at that moment and, during the administration of President Santos, opposed the signing of a peace agreement between the government and the FARC guerrilla.

This phenomenon of permanent administrative reform poses important conceptual, empirical, and methodological challenges to the current knowledge on the termination of public organizations in non-Global North countries. As Jae Young Lim (2021) puts it in a recent article about the evolution of research on the causes of termination in public organizations, “a large number of countries therefore continued to be absent from a scholarly understanding of organizational termination. Therefore, there needs to be further research on organizational termination in single non-European countries, as well as studies conducting cross-country comparisons” (199). In Latin America, there are important reasons that call for a greater academic understanding of the termination of organizations. For example, changes in the structure of public administration have been a constant throughout the region since the 1980s, and in all these reforms, presidents have played a leading role in the reorganization of the public sector, given the constitutional powers they possess. Also, unlike the United States with its two-party system, the Latin American party system tends to be multiparty. The fact that many political parties can opt for the executive branch and that the legislative branch is divided among many benches may influence in a different way the decision to terminate a public organization.

Taking Colombia as a case study, this article examines the factors related to political incentives for the termination of public entities. In general terms, it suggests that political turnover has a negative effect on the duration of public organizations. However, this effect differs according to the size of the governing coalition. In other words, the greater the number of parties in the governing coalition, the higher the bargaining costs incurred by the president and, therefore, the lower the incentives to terminate a public organization.

According to Kuipers, Yesilkagit, and Carroll (2018) , studies on the mortality and survival of public organizations have sprung from two different perspectives. The first one comes from public administration. Here the organizational characteristics of a given entity are determinants for explaining its establishment, prosperity, and termination. Under this approach, public organizations adapt to their environment and, therefore, changes in the administrative structure of government bring organizations to seek to adjust to the changing setting on their own. The second perspective comes from political science. According to this approach, the status, functions, and structural forms of public organizations, as well as their changes, are political actions that represent political control over the public sector. While the former approach emphasizes organizational stability, studies that see political control as the principal explanation for survival focus on organizational discontinuity. This article builds on this last point of view and, consequently, looks at the academic literature pertaining to this topic.

The paper is divided into six sections, including this introduction. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on mortality in public organizations and identifies the crucial political factors influencing cessation. Based on this literature review, causal factors are hypothesized. Section 3 explains and justifies the selection of Colombia as a case study. Section 4 describes the data, variables, and methods. The fifth section presents the results while the last section offers some conclusions.

1. Termination of Public Organizations Because of Political Turnover: What do We Know?

Besides the seminal work of Kaufman (1976) , in which the author examines 421 executive departments existing in the United States between 1923 and 1973, the most representative study on the survival of public organizations is the research by Lewis (2002) . This author starts with a critique of Kaufman’s work, in which he argues that, although public organizations are not immortal, they tend to be quite durable. Lewis believes that this conclusion is erroneous, mainly due to methodological reasons. For example, the data set used by Kaufman does not include agencies created prior to 1923 that became extinct before that year. It also excludes agencies created after 1923 that terminated before 1973. Finally, Kaufman only examines executive departments in his study, leaving out other types of entities. Therefore, Lewis considers that Kaufman’s sample and results are biased toward long-lived agencies.

With this in mind, Lewis (2002) evaluated the probability of survival in 426 public agencies, controlling for factors such as unemployment, among others. Lewis’s list of entities included all administrative agencies created in the United States between 1946 and 1997. The analysis left out entities such as advisory commissions, multilateral agencies, and educational and research institutions. The author found strong evidence that federal agencies are at greater risk of termination when faced with political turnover. If a political party controls both the executive and legislative branches, it is easier to eliminate or downsize organizations that have been supported by the party’s opponents. Lewis concluded that public organizations are far from immortal and that political turnover exposes organizations to the threat of termination or downsizing.

Based on Lewis’s work, Boin, Kuipers, and Steenbergen (2010) assessed the impact of institutional design of new public organizations on their survival chances. Using organizational life span as a dependent variable, measured as the duration in years between the creation and termination of an organization, these scholars analyzed 63 of the so-called New Deal organizations initiated under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first term. Using a Cox regression model, the authors found that design features do matter, but they matter in different ways during different life phases of public organizations. Institutional design may protect an organization in its early years against the potential effects of environmental dynamics. However, these favorable effects may ware off as the organization matures.

According to Carpenter and Lewis (2004) , a public entity’s risk of being terminated for political reasons is linked to its age. Younger organizations are less likely to be ended because they receive greater political support. As young entities, their creators or sponsors, who have a vested interest in these entities, are likely to be still in the legislature and can defend them. On the contrary, things are different a decade after the creation of an organization. By then, the risk of the organization being terminated increases, not only because there is more information about its good or bad functioning but also because the protective shield of this organization in the legislature may have diminished. Another finding of Carpenter and Lewis, based on the statistical models used, is that there is no causal relationship between budget deficit and the elimination of public organizations.

In a similar direction, Greasley and Hanretty (2016) studied the duration of 723 public organizations in the United Kingdom between 1985 and 2008. These authors concluded that public organizations face higher risks of being eliminated under right-wing governments. This result is especially robust when governments operate under low or moderate budgetary pressure. On the other hand, left-wing governments tend to terminate public organizations when the country is at risk of recession. However, when this occurs, left-leaning governments prefer to eliminate public organizations created more recently while protecting older organizations.

James et al. (2015) were also interested in the determinants of the survival of government agencies in the UK. Their analytical concern was to observe whether the effects of political turnover, studied for the two-party presidential system in the US, were observable in parliamentary systems such as the UK. Their results suggest that “agencies are at increased risk following a transition in government, prime minister, or departmental minister and in cases where the actors in the political executive overseeing an agency are different to those establishing it” (1). This occurs because, given the brevity of ministers in office, they find in the abolition of agencies a way to signal their policy preference, leaving their mark. It is also a means of attacking the creation of public organizations by previous ministers.

Park (2013) explored the determinants of structural changes in public-sector organizations in Korea. The statistical model developed by the author suggests that the survival of public-sector organizations depends on political rather than other factors, such as organizational characteristics or effectiveness. Specifically, the termination of a public organization is contingent on political change and considerations related to the political cost-benefit ratio in ending the organization and variables such as presidential tenure, institutional changes, and social demands for reform.

The above discussion has resulted from research conducted mainly in the US, European countries, and Korea. The causes of termination in public organizations are still absent from a scholarly understanding in countries other than those mentioned (Lim, 2021), especially in Latin America. There are some academic works in the region that offer an overview of how political control over public organizations can affect the organizational structure of these entities more than the process of termination itself. In the framework of delegation theory, much of the literature has studied the genesis of autonomous organizations in the context of state reform. According to this approach, some public organizations, such as regulatory agencies, are created with special organizational features that insulate them from political pressures (Ballinas Valdés 2009, 2011; González and Tanco-Cruz 2019; González and Verhoest 2016; Jordana and Ramió 2010; Sifontes 2005).

In general terms, the literature review agrees that the national political environment can play a significant role in the decision to terminate or not public organizations. Organizations suffer from both political changes and the political ambitions of those who come to power. These studies also agree that there is no solid evidence correlating the performance of public organizations with the decision to end them. From this perspective, public organizations emerge and are transformed by political conflicts and strategic negotiation between coalitions of rational actors. In this optic, the choice of organizational structures of public entities are not only a management tool or an instrument for improving governance but also a political action (Moe 1989; Macey 1993; Lewis 2002; Wood and Bohte 2004) .

Given that political systems differ from one country to another, the obvious question is to what extent can the results of the academic literature presented be generalized to presidential political systems such as Latin America? For example, are the findings on the mortality of agencies in the US also relevant for Latin American countries? To what length can the analytical concepts used in the case studies of parliamentary systems be applied to different political systems?

Therefore, to contribute to understanding the termination of public organizations in countries of the Global South, this paper tests the hypotheses proposed by the literature, adjusting the theory to the characteristics of the Latin American presidential system. In other words, we extend the theory of government agency termination from the US and European countries to Latin American presidential systems.

Following the literature, we explore whether public organizations are at a greater mortality risk when faced with government changes. A change in the presidential administration allows the new ruling party to reshape the administration towards its own image, eliminating public organizations it opposes. Therefore, the first hypothesis observes whether political rotation increases the risk rate of administrative agencies.

H1: Political turnovers negatively affect the survival of public organizations.

Also, since the executive and the legislative are two separate powers in presidential systems, preferences for a given organization may oppose each other. For example, a new president’s initiative to abolish an organization may fail due to opposition from the legislative branch. However, if one party controls both the executive and legislative branches, it will be easier to suppress organizations. This leads us to our second hypotheses.

H2: The greater the number of parties that form part of the government coalition, the lower the probability of terminating a public organization.

Finally, under difficult fiscal conditions, the government tends to rationalize its expenditures, especially the resources spent on the operation of the state. Consequently, the fundamental objective of public administration renewal programs is an adequate balance between operating and investment budgets, maximizing the latter’s impact by eliminating entities whose operating costs threaten the sustainability of public finances. Therefore,

H3: Lower economic growth increases the likelihood of the termination of public organizations.

2. Setting the Colombian Case

To understand how presidents eliminate public organizations as part of reshaping the administration toward their own image, we analyze the Colombian case, which is a good test case for three reasons. First, there is a significant variation in the suppression of public organizations. Between 1958 and 2018, the presidents who moved into the Casa de Nariño undertook 193 suppressions of public organizations. Second, Colombia has made considerable modifications to its political system. From 1958 to 1991, Colombia had a two-party government system. From 1991 on, a constitutional change eliminated entry barriers for new parties, transforming the party landscape. The traditional Liberal and Conservative Parties lost ground, making it quite hard to win the presidency without a multiparty coalition. And third, Colombia shifted among two distinct patterns of agency termination. The first one was a rather gradual and stable period that coincided with the bipartisan system; the second one resembles a rollercoaster ride with frequent up-and-down elimination of organizations, a period initiating with the arrival of multipartyism. This development allows testing the effect of presidential coalitions on agency termination under a two-party system and a multiparty one.

A. The Colombian political system and administrative transformations

Colombia is a presidential democracy in which power is divided among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches whose dominions and duties are contemplated in the Colombian Constitution. The Colombian political system is characterized by multiple parties that race to control the bicameral legislature and the presidency. This system is the result of the enactment of the 1991 Political Constitution of Colombia, which eliminated the barriers to political participation existing until then. Between 1958 and 1974, Colombia lived a period known as National Front. It consisted of a political agreement between the Liberal and the Conservative party, establishing an exclusive democracy through a power-sharing formula between these two parties. The main characteristics of this period were the alternation of the presidency during four constitutional periods (16 years) and the distribution of ministries and the bureaucracy following a partisan balance; congressional seats were also evenly distributed, as well as the members of the Supreme Court of Justice (Hartlyn 1988) . By 1974, the National Front’s rules were relaxed; however, until the end of the 1980s, the Liberal and the Conservative party maintained bipartisan control of the government and were able to exclude other movements from political competition.

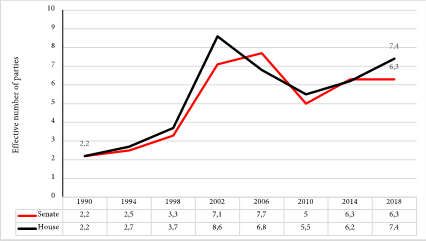

One of the main purposes of the new 1991 Constitution was to balance the access to electoral participation and representation between the traditional Liberal and Conservative parties and new political movements and parties. As a result, the effective number of parties increased. As shown in Figure 1, between 1990 and 2018, this number in Colombia increased from 2.2 to 6.3 in the Senate and from 2.2 to 7.4 in the House of Representatives.

This fragmentation makes it increasingly difficult for presidents to have a majority in Congress, forcing them to negotiate with other parties to push their legislative agenda. It means that the Senate requires the consolidation of inter-party agreements to approve the bill that gives the president of the Republic the capacity to reform the state. For example, when the Senate discussed the approval of powers to President Santos (2010-2014), the leftist party, Polo Democrático, withdrew itself from the hearings and instead announced a lawsuit against the law before the Constitutional Court.

The responsibilities and competencies of the president are defined by the 1991 Constitution. The president and their ministers are responsible for shaping public policy guidelines and prioritizing public expenditure. Therefore, the president, through their cabinet, plays a significant role in setting the legislative and policy agendas. This task is guaranteed by a series of constitutional powers, grouped around three axes: legislative initiative, veto power, and the president’s faculties to legislate. Although these presidential powers give them significant operational space in the formulation of public policy, as highlighted by Duque Daza (2014) , presidents are subject to considerable pressure from the parties and Congress and, therefore, are bound to negotiate with them.

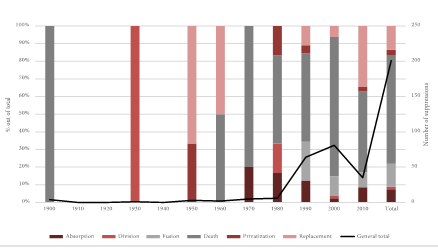

Regarding state administration, Sanabria-Pulido and Leyva (2022) underline that public administrative reform has been a permanent trait of the governance environment in Colombia since the 1980s. This trajectory of administrative changes speeded up after the enactment of the 1991 Constitution. Article 189 of the Constitution and its legal development through Laws 489 of 1998 and 790 of 2002 authorize the president to restructure, suppress, or merge public organizations of the central administration. As shown in Figure 2, the suppression rate of public organizations takes off since the 1990s, from 6 during the 1980s to more than 35 in the 2010s. The termination of public organizations is understood for the purpose of this study as the range of events from replacing one agency with a different one to absorbing one agency by another. Behind this definition is the idea that the organization considered as terminated has ceased, totally or partially, its original functions.

Source: Own elaboration based on data.

Figure 2. Types of Organizational Termination Events by Decade

In addition, the Constitution and the law authorize Congress to delegate extraordinary faculties to the president for a limited time (six months) to create new administrative structures at the central government level. In fact, in the last 30 years, Congress has granted these extraordinary powers to all presidents during their term in office (Table 1).

Table 1. Powers to Reform Public Administration

| President | Powers to reform public administration |

|---|---|

| César Gaviria Trujillo (1990-1994) | Extraordinary powers granted to the president by Article 20 of the Constitution. A total of 61 decrees were issued through which he restructured public administration, seeking to reduce the size of the state. |

| Ernesto Samper Pizano (1994-1998) | His presidency created the Plan for the Improvement of Public Management, the Commission for the Rationalization of Public Expenditure, and the Committee for the Public Administration Reform. Seven entities were abolished, and four public organizations were merged. |

| Andrés Pastrana Arango (1998-2002) | He presented to Congress draft Law 489 of 1998 (Basic statute of organization and functioning of public administration). Based on this law, he enacted a package of 17 decrees under the framework of state modernization. |

| Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2002-2006) Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2006-2010) | He created a public administration renewal program. He carried out an institutional redesign aimed at 302 entities of the executive branch of national order. Of these, 54 modified their organizational structure, 34 were liquidated, 9 were created, 5 changed their assignment, 4 were merged, 3 were split, and 1 was decentralized. The number of state organizations was reduced by 30, from 302 in 2002 to 272. |

| Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (2010-2014) Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (2014-2018) | Law 1444 of 2011 granted extraordinary powers to the President for six months to modify the structure of public administration. Approximately 80 decrees were issued reforming many state entities. |

| Iván Duque Márquez (2018-2022) | In the draft Sustainable Solidarity Law project, the executive asked Congress for extraordinary powers to eliminate, merge, restructure, or modify entities, agencies, and dependencies of the executive branch. |

Source: Own elaboration based on data.

Thanks to these powers, presidents have tools by which they can unilaterally alter the status quo and block changes proposed by other actors, including former presidents. For example, as mentioned in the introduction, the Ministry of Environment was created during the administration of President Gaviria (1990-1994). Later, during the first administration of President Uribe (2002-2006), it was merged with five other ministries. Subsequently, with the arrival of President Santos to power (2010-2014), these six ministries came back to life, including the Ministry of Environment.

3. Empirical Strategy

To assess our hypotheses, we used an original database containing longitudinal information on public organizations in Colombia for the period 1958 to 2020. The database has 415 observations on the organizational characteristics of each entity, including its legal nature, the sector to which it belongs, changes in the administrative structure, the year of creation and suppression of each one, and age understood as the number of days the entity has remained active. In addition, a complementary database was constructed incorporating the following information: i) characteristics of the political system and electoral environment in each presidential period, such as coalition size during each government, the effective number of parties (NEP) in the upper and lower houses, the political orientation of the president-elect, and the legislative contingent of the president in the upper and lower houses; ii) periods of political change, such as the change of government every four years, and institutional changes, such as the enactment of the 1991 Constitution.

The complementary database and the incorporation of variables associated with the political system is essential because, as mentioned above, the duration of public entities is determined not only by their productive performance but also by political predispositions. Hence the need to evaluate the organizational characteristics of each entity and the political and institutional factors that influence its environment.

For the case studied, a public entity is understood as any organization created by the Constitution or by law, with public participation and where an administrative, commercial, or industrial function is fulfilled. Based on this definition, eleven types of public entities were included: ministries, administrative departments, public establishments, superintendencies, special administrative units, mixed-economy companies, state agencies, scientific and technological institutes, councils, presidential programs, and secretariats.

The dependent variable used in the analysis is the duration of an organization. This variable was operationalized as the number of days an entity lived from its creation to its suppression. As mentioned earlier, the termination of public organizations is understood, for the purpose of this study, as the range of events (structural transformations) that imply that an organization ceases totally or partially its initial core functions. These events can take the form of replacement, fusions, divisions, absorptions, etc.

The model used nine independent variables to capture the organizational characteristics and political factors that may affect the likelihood of public entity termination. The first variable is coalition size. This categorical variable is coded from 1 to 8 according to the number of parties within the presidential coalition. It is expected that the greater the number of parties within the coalition, the lower the probability of suppressing a public entity. Second, the year of creation shows whether an entity was created during the first year of government or in subsequent years. Third, the political rotation variable marks the periods when there is a change in government administration. The variable takes the value of 1 when there is a presidential change. The fourth variable is public expenditure, measured as a percentage of GDP. The fifth and sixth variables are dichotomous, capturing whether the entity pertains to the economic sector, such as the Ministry of Finance, and whether it has undergone structural changes in its administrative organization, such as adding new internal units. Institutional change is the seventh variable, which takes the value of 1 when structural changes to the Colombian political system took place, particularly in the years 1958 (start of the National Front agreement), 1968 (Constitutional reform), and 1991(enactment of the new Constitution). The eighth variable is the government’s political orientation, which captures the effect on agency termination of whether the elected party belongs to the center-left, center-right, or right on the political spectrum. To this end, a categorical variable, coded from 0 to 2, was used based on the classification model proposed by Fergusson et al. (2021) in the study “The Real Winner’s Curse.” This coding model consist of two fundamental stages in which the flag issues and the base policies of the parties are considered. In the first stage, left or right parties are classified according to whether their name or slogan directly incorporates concepts such as “socialism,” “communism,” “social-democracy,” or “conservative,” “Christian-democratic,” “right,” respectively. In the second stage, the positioning of the base policies in the statutes of each party is assessed. It is worth mentioning the case of the Partido de la U, which shares characteristics of both political orientations and additionally calls itself of center; therefore, it was classified as such. And, finally, the ninth variable is presidential period measured through a categorical variable that takes the value of 1 to 4 according to the year of government elapsed.

Based on the above, we conducted a survival analysis, a statistical method that allows estimating the probability of occurrence of a particular event during an established period. In other words, the survival analysis is helpful for evaluating the relationship between time without failure and a series of covariates that takes place within the period under study. For the present case, we understand as action the time that the entities last exercising their functions and, in turn, as failure, the event in which a public entity is terminated (ceased). It should be considered that some entities remain active, i.e., they do not go through the event of agency termination during the period under study, so it is impossible to cover the entire period of organizational life of these entities. This phenomenon is known as censorship. The existence of this phenomenon justifies the use of non-parametric estimators like those of Kaplan and Meier (1958) instead of standard statistical models, such as ordinary least squares or even logit/probit models, which would return inconsistent results since they do not incorporate censored and non-censored information in different probability functions (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones. 2004, 18) .

Finally, the Cox regression model (1972, 1975) was used to identify the predictor and protective factors affecting the suppression risk level of an entity. A predictor factor is one that increases the probability o0f occurrence of an event, in this case, the suppression of an entity, while a protective factor decreases this probability. The estimated model incorporates the nine independent variables mentioned above to identify the influence of each variable on the probability of entity suppression during the studied period. This method is relevant because it allows estimating the relationship between a series of covariates and failure time, even though it has limitations regarding the existence of adjacent events and a possible overestimation of the variance. However, these are solved by using Breslow’s (1974) approximation, which is useful in cases where the number of adjacent effects is relatively low, and by adjusting the model based on robust variance estimates. Finally, compliance with the proportional hazards assumption was verified to corroborate whether the estimators obtained from the adjusted model are consistent and unbiased.

4. Results

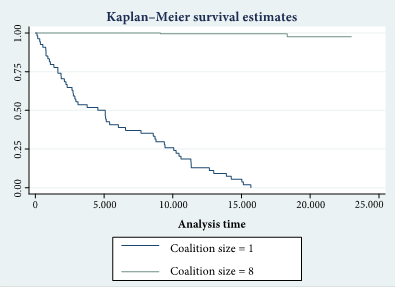

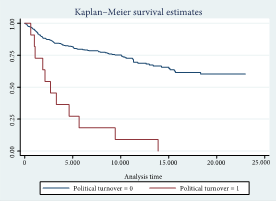

The figures in this section illustrate the results of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves, which we used to evaluate the first two hypotheses proposed in this article: H1: Political turnovers negatively affect the survival of public organizations, and H2: The greater the number of parties that form part of the government coalition, the lower the probability of terminating a public organization. In this context, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves were set for the categorical study variables associated with the characteristics of the political system.

The third hypothesis-H3: Lower economic growth increases the likelihood of the termination of a public organization-is a continuous variable and, therefore, it was not possible to use Kaplan-Meier curves to assess it.

Figure 3 plots the probability of survival for two variables: coalition size and political rotation. For coalition size (figure to the left), the survival curves are shown for two specific cases: when dealing with single-party governments and, on the contrary, when there is extreme multipartyism with coalitions involving eight political parties at the same time. High stability of public entities is evident during governments with the highest number of parties within the coalition compared to periods where the government is composed of a single party. More specifically, after 5,000 days in office, a public entity has a 40% probability of survival during a single-party government period, while that same entity would have twice the survival probability during periods of multi-party coalitions.

Source: Own elaboration based on data

Figure 3. Estimated Survival of Public Entities (days in action)

When it comes to political rotation (figure to the right), there is evidence of less stability of public entities during periods of political rotation compared to periods where there is no change of government. In this case, a public entity that has been active for 5,000 days has a 25% probability of survival in years of political rotation versus an 80% probability in years when there is no change of government.

Figure 4 shows the results of the survival curves for the variables of institutional change, the government’s political orientation, and the presidential period. The survival curve for periods of institutional change (figure to the upper left), such as the promulgation of the 1991 Constitution, exhibits a negative and greater slope compared to the curve that represents periods of institutional stability, providing evidence that the likelihood of survival of public entities is less during periods of institutional change. Regarding the government’s political orientation (figure to the upper right), public entities show higher stability during right-wing governments (when the variable takes the value of 2) relative to periods where the executive belongs to a center-left party. For example, at the 5,000 days mark, the probability of an entity being abolished increases by 35 percentage points if the government in office is center-left, compared to a right-inclined government.

Source: Own elaboration based on data

Figure 4. Estimated survival of public entities (days in force)

Finally, regarding the presidential period (bottom figure), the graph shows four curves corresponding to the year of government period elapsed (1st to 4th year). The results indicate that both during the first and last years of government, there is less stability in public entities. Both survival probabilities are similar in specific cases. For example, when entities have lived for 6,000 days, both curves intersect with the same probability of survival of only 25%, compared to the second and third years of government, where the probability of survival is much higher, close to 50%, and 90%, respectively.

Table 2 presents the results of the Cox regression model (1972, 1975). If the coefficient is less than 1, the variable is considered protective since it decreases the probability of failure of public entities. Similarly, if the coefficient is greater than 1, it is understood as a predictor factor, increasing the probability of public entities being suppressed. Regression results indicate that five of the nine variables included were significant: coalition size, political rotation, public expenditure, presidential period, and the year of creation. Of these five variables, two are protective, and three are predictors.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model (Breslow method)

| Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coalition size | 0.547*** (0.0386) | |

| Creation during the 1st year of government | 2.165***(0.) (0.240) | |

| Political turnover | 4.831*** (0.474) | |

| Public expenditure | 0.880*** (0,0419) | |

| Entity belongs to economic sector | 0.862 (0.220) | |

| Change in the organizational structural arrangement | 0.800 (0.197) | |

| Institutional change Government's | 0.813 (0.320) | |

| Orientation ( 2 when right) | 1.201 (0.134) | |

| Presidential period observations | 1.812 *** (0.0846) | |

| 415 | ||

Source: Own elaboration based on data.

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.13

The two significant variables considered protective factors for agency stability are coalition size and public expenditure. With 99% confidence, the regression results confirm that the larger the size of the government’s coalition, the lower the probability of a public entity being suppressed. A plausible explanation is that the greater the number of political actors that make up the coalition, the larger the negotiation costs the executive needs to incur to suppress any given entity. This result reaffirms the trends seen in the Kaplan-Meier survival curves and our main hypothesis.

Public expenditure is also a protective factor. When more resources are available in the economy, this allows for greater government spending, and the probability of suppressing public entities decreases; in other words, under tight fiscal conditions, governments seek to rationalize their expenditures by eliminating entities. At the same time, prosperous fiscal conditions make it is easier for governments to sustain the operating costs of public entities, allowing higher agency stability. This result validates the third hypothesis that we proposed in this paper.

The predictor variables found to be significant are political rotation, the dichotomous variable capturing whether the entity was created during the first year of government, and the time elapsed during the presidential period. The first variable validates the hypothesis that, during political rotation periods, public entities have a greater probability of being abolished. This makes sense, given that a change in presidential administration encourages the new ruler to reshape the public administration scheme, for example, by eliminating the entities they oppose. Therefore, the three hypotheses were confirmed, placing political rotation as one of the primary causes for the termination of public entities with the largest marginal effect in the model.

In addition, the moment of agency creation is also a predictive factor in the likelihood of suppression of public agencies. Public organizations created during the first year of a presidential term have a higher probability of being terminated in the following government term. In other words, young agencies face a greater risk of termination than older ones, which reflects the power granted to the president by the Constitution to request Congress for special faculties to reform the structure of the public sector during the first year of government.

Finally, the risk coefficient associated with the variable of time elapsed during the presidential period shows that the longer the time elapsed, the greater the probability of suppression. This is consistent with what was observed in the survival curves, indicating that the first and fourth years of the presidential period are when public agencies have a higher risk of suppression.

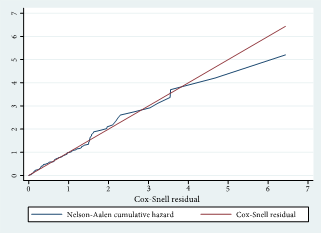

Figure 5 examines how well the model fits based on Cox-Snell residuals in contrast to the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function. A model is considered to correctly fit the data when the cumulative function of the Cox-Snell residuals and the Nelson-Aalen hazard function follow a 45-degree straight line. The concentration of the censored data at larger time values might evidence a deviation of the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function in the right tail, which is of no particular concern since these fluctuations over time are normal in a model with censored data. Additionally, when testing for compliance with the proportional hazards assumption, no statistical evidence supports the premise that our model violates the Cox proportional hazards assumption. Moreover, a robust variance-covariance matrix was used to avoid biased results; thus, it can be concluded that the model fits the data.

Conclusions

This article aimed to assess the main conclusions of the academic literature from the Global North about the termination of public organizations on multiparty presidential systems such as Latin America. In particular, the study scrutinized “political control” explanations in the continuous transformations of Colombia’s administrative public sector. In this context, it evaluated three hypotheses: i) whether political turnovers negatively affect the survival of public organizations; ii) whether the number of parties that form part of the government coalition affects the probability of terminating a public organization, and iii) whether lower economic growth increases the likelihood of the termination of a public organization. We found that the political factor is relevant in the decision to terminate an organization.

The data show that a change in the presidential administration allows the new president to reshape the administration according to their interests, which includes eliminating public organizations that they consider contrary to their government plan. The data analysis also indicates that the larger the size of the government coalition, the lower the probability of a public entity being eliminated, which might be due to the transaction costs associated with negotiations among more political actors. Also, the evidence suggests that presidents are more likely to end public organizations during the first year of their government than during the years of government consolidation. A possible explanation might be that Colombian presidents must request from Congress special powers to reform public administration. Historically, this occurs during the first six months of each incoming government when it is more likely to be interested in accommodating the administrative structure to its government program. Finally, the model also suggests that, under difficult fiscal conditions, governments tend to rationalize expenditures by terminating some organizations; on the contrary, when the economy is more prosperous, the probability of entity elimination decreases.

These results suggest that, in eliminating public organizations, presidents find a way to signal their policy intent and politically control the government structure. However, this capacity is limited. Both minority presidents and those who base their administration on multiparty coalitions face difficulties for ending public organizations as they confront opposition or higher bargaining costs. Presidents who hold a larger legislative contingent in Congress face fewer difficulties, and, therefore, the risk of public organization termination increases.

We know that it is impossible to reduce the termination process of a public organization to a dichotomous definition, where the public entity survives or does not survive. We are also aware that the organizational events-merger, privatization, division, absorption, replacement-we include here as the termination of a public organization may result from specific and different political explanatory variables. Future research could widen the spectrum of analysis on patterns of organizational termination to capture different types of endings.

Finally, the shortage of studies on organizational termination in single Latin American countries and of regional studies conducting cross-country comparisons provides space for a broad research agenda, which ranges from understanding how political bargaining between the president and political parties works when deciding whether to terminate an entity to deepening the explanatory variables and patterns that account for organizational termination. For example, under what political conditions does the president decide to abolish, merge, restructure, or modify an organization, or what type of public organizations are more susceptible to termination? This last suggestion implies deepening the study of how some public organizations are endowed with structural features such as political insulation, which gives them higher survival chances than those without these birth characteristics.