Introduction

Much of the research on conflict resolution has focused on the conditions for getting parties involved in a conflict to sign a peace agreement (PA). Less attention has been paid to what happens next: implementation and the actors’ capacity to facilitate the transition from war to sustainable peace (Jones 2011; Joshi and Quinn 2015; Lyons 2016; Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). As argued by Stedman (2001), after signing a PA, numerous threats-such as difficulties in the environment or spoilers-can hamper the goal of achieving lasting peace. To counter such threats, adequate strategies for implementation are, therefore, of utmost importance.

Joshi, Quinn, and Regan (2015) refer to research on the implementation of peace agreements and their impact on post-accord dynamics “as theory-rich but data-poor” (551). Lyons (2016) has argued that most peace agreements are flawed, to varying degrees, due to the particularities of the peace process. Given that implementation can provide opportunities to strengthen weak agreements, the process is more likely to lead to sustained peace if it is flexible and includes considerations beyond the original text. In other words, the content of a PA itself does not bring peace unless it is successfully implemented (Jones 2011; Lyons 2018).

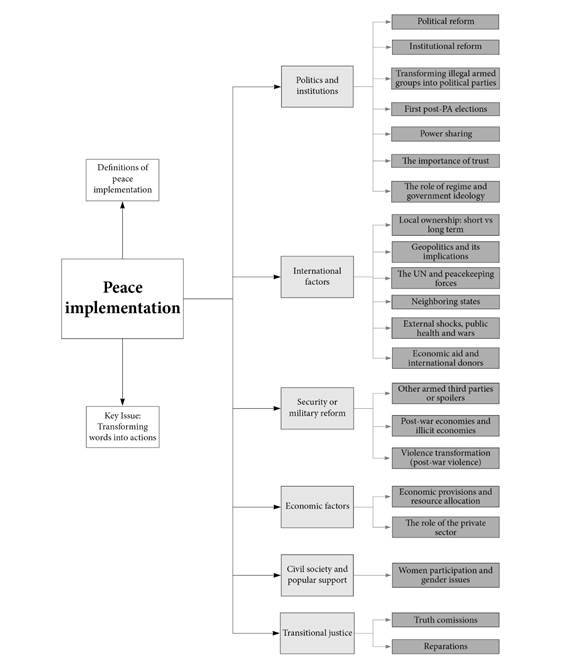

In this working paper, we offer a review of the available literature on the factors shaping peace agreement implementation (PAI). The main difficulty for PAI is translating words into action to transform societies that have experienced armed conflict (Bekoe 2003; Jones 2011). Therefore, we analyze the main factors or variables involved in peace implementations using a variety of sources and examples to illustrate the challenges. We begin by presenting several definitions, characteristics, and effects of peace implementation; we then analyze what we believe to be the main factors or variables involved in successful implementation. We provide a general overview of the factors that will give scholars a broad sense of the most important debates within this literature.

1. Laying Out the Problem: Definitions and a Model of Implementation Complexity

Peace implementation refers to narrow, short-term efforts to get the parties involved to comply with their commitments to peace (Stedman 2001; Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). Stanley and Holiday (2002) suggest that for peace agreements to lay the foundations for a more democratic post-war environment, implementation needs to move quickly and rearrange political institutions so that newly incorporating elements of the polity have sufficient guarantees. In a similar vein, Joshi and Quinn (2015) argue that the daily work of implementing a PA implies a continued “negotiation, renegotiation, a sustained dialogue, and continuous dispute resolution between […] sectors of the government and population segments affected by the implementation” (5). Lyons (2016) extends this to describe peace implementation as “a period of constant evaluation and re-evaluation in a constantly shifting context” (72), marked by uncertainty and risk and requiring a flexible process that tests perceptions and feelings towards the viability of a durable peace (Lyons 2018). A review of the cases where peace agreements have been signed shows much diversity in how peace is established and built in each scenario (Crocker, Hampson, and Aall 2005; Höglund and Kovacs 2010). Thus, successful peace implementation may be referred to as a “flexible process of creating and re-creating ripeness so that broad coalitions in each of the major parties continue to favor non-military strategies” (Lyons 2016, 73).

Several scholars have also demonstrated the need for a set of subgoals to accomplish peace implementation (Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). This is further explored by Joshi, Quinn and Regan (2015), who argue that implementation processes often unfold in a “reciprocal fashion” whereby actors condition their continued participation and compliance in the process to their counterpart’s level of participation and compliance. This brings forth a great deal of uncertainty surrounding implementation and the probability of the parties honoring commitments (Bekoe 2003). Bekoe (2003) argues that there are several potential deal-breakers in the implementation process that are impossible to know in advance, even though they may also encourage compliance. In a similar vein, Walter (2011) has shown that the dominant form of armed conflict tends to be recurring civil wars, due to a “conflict trap” (i.e. countries that experienced civil war are more likely to experience renewed episodes of violence). Recurrence is a consequence of failing to address some of the causes of war such as economic factors and state capacity (Collier, Hoeffler, and Söderbom 2008; Walter 2011).

One main challenge of peace implementation is transforming words into actions (Jones 2011). Lyons (2018) argues that to correctly implement a peace negotiation, this must be a process of redefining the terms of the agreement rather than its narrow interpretation. Furthermore, Lyons (2016) suggests that if peace implementation focuses on strict adherence to the agreement, post-war periods can perpetuate the polarized conditions of wartime. Jones (2011) also argues that often in PAI actors proceed quickly without having an accurate map of the hazards and risks of a post conflict society. Therefore “strategic coordination” is required (Jones 2011).

Jarstad and Nilsson (2008) argue the most important provisions to be implemented are the ones that denote greater concessions for the parties because they reflect a high degree of commitment. Moreover, they quantitatively demonstrate that when the parties engage in costly concessions, the likelihood of peace prevailing is higher (Jarstad and Nilsson 2008). Mac Ginty, Joshi, and Lee (2019) have also shown that, in most cases, provisions in peace agreements are not meant to be implemented independently but in accordance with each other. Moreover, the implementation process of a PA is a form of peacebuilding integrated into a collection of parallel processes aimed at promoting reconciliation, fostering better state-society relations, and addressing the root causes of armed, social, and political conflicts (Joshi and Quinn 2015).

This brief outline gives us a departure point towards the challenges of peace implementation. In the coming sections, we focus on specific provisions, challenges, or variables that we have identified as key to peace implementation.

We conceive the implementation process as composed of multiple temporal stages (short to long-term), layers (from international to local), and dimensions (including politics, justice, the economy, and culture). In an implementation phase, it is necessary to address all these in parallel, as they exert mutual impact and shape each other’s progress. We think of this complexity as a multilayered, multi-thematic, and temporally diverse model in which what is needed for implementation-and implementation in itself-intersects with other ongoing social, political, and economic processes at the international, national, and local levels. Figure 1 describes this model. The following sections discuss each of these topics.

2. Factors Affecting Peace Agreement Implementation

a. Politics and Institutions

Political reform

One of the most studied provisions for a successful PA implementation is political reform, which comes in multiple shapes and forms, depending on the context and content of the agreement. The most documented implementation challenges are power-sharing agreements, the political participation of former combatants, and transitional elections. Joshi and Quinn (2015) have argued that civil wars are less likely to recur in cases where higher levels of democratization were achieved after peace agreements; therefore, a positive strategy for establishing lasting peace is implementing a set of mutually agreed-upon socio-political reforms. According to Joshi and Quinn (2015), 76 % of PAs contain provisions for electoral reform aimed at making the electoral system more representative, 55 % additionally include constitutional reforms, and 50 % incorporate political power-sharing arrangements. These provisions seek to create a more accountable, politically open, inclusive, and representative political scenario that supports armed groups’ transformation into legitimate political parties. In this section, we explore this topic in greater detail.

Institutional reform

Scholars have pointed out that institutional transformation is key to a steady and flexible implementation process (Lyons 2016). Jarstad and Nilsson (2008) have identified that power-sharing institutions-including political, economic, territorial, and/or military institutions-built during implementation are key for durable peace. Thus, a transition from war to peace is also a transition from institutions designed for conflict and war to institutions that can effectively respond to the challenges of post-war societies (Lyons 2016)-a process of “creative destruction of wartime institutions” (77) through proposing, modifying, and creating new institutions.

Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim (2013) argue that institutional reform is an appealing option to shape state institutions like the system of government, electoral systems, party regulations, territorial state structure, the judiciary, and the security sector to promote sustainable peace and prevent the recurrence of conflict. Nevertheless, because it is a challenging and time-consuming task that requires institutional design and involves a large group of actors, institutional reform should aim at preventing the recurrence of organized violence by examining why societal conflict escalated into such a form. Additionally, they argue that not only the causes of war but also the war’s dynamics may crucially impact the design of post-war institutions (Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim 2013). One reason why institutional reforms are time-consuming and complicated to implement is that they often require enacting new laws and institutions (Jarstad and Nilsson 2008). Based on their logic of “costly signaling,” Jarstad and Nilsson (2008) demonstrate that when parties “engage in such costly concessions peace is more likely to prevail” (211).

External actors, such as international organizations, can play a significant role in determining institutional outcomes during implementation (Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim 2013). Mac Ginty and Richmond (2007) argue that heavily engineered governance institutions and frameworks exported to post-conflict zones as part of post-conflict reconstruction process can be difficult to implement, especially where acute poverty and underdevelopment coincide with conflict. It is necessary to track the effects of institutional design in various social and cultural contexts, including ethnic and religious groups (Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim 2013; Crocker, Hampson, and Aall 2005). Thus, Mac Ginty and Richmond (2007) argue that “the process of building institutions and designing must be locally owned and reflect the local identity and must quickly and demonstrably benefit most of the population” (493).

It is also important to consider the role of informal institutions or hybrid forms as institutional arrangements. Ansorg, Haass, and Strasheim (2013) point out that an interesting example could be a security reform that not only considers the national army but also “ethnic militias and neighborhood watches that continue to operate and are tacitly accepted by society because they may more effectively guarantee security for the local population” (22).

Transforming Illegal Armed Groups into Political Parties

Several scholars have argued that the demilitarization and normalization of politics or the transformation of armed groups into political parties are some of the most important provisions to be implemented (Joshi and Quinn 2015; Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). Implementing these provisions frequently stops violence and provides a political alternative to ex-combatants (Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). Therefore, a concerted effort to transform armed groups into viable political parties plays a crucial role in consolidating democracy and strengthening the prospects for war termination (Lyons 2016). Furthermore, Lyons (2016) argues that building effective political parties increases the likelihood of demobilization because armed groups see that they can protect their interests through political rather than military means. These reforms, which in some cases guarantee seats in the legislative branch, are critical to the ex-combatants’ ability to overcome a political impasse that would otherwise often lead to renewed violence (Joshi and Quinn 2015).

The First post-PA Elections

Elections are a key element to rehabilitate countries devastated by armed conflict (Collier, Hoeffler, and Söderbom 2008; Flores and Nooruddin 2012). The first elections after a PA has elections are a key element to rehabilitate countries devastated by armed conflict (Collier, Hoeffler and Söderbom 2008; Flores and Nooruddin 2012) been signed represent one of the main challenges to implementing political reforms; in fact, postponing elections and initiating demobilization before elections lengthen the duration of peace (Joshi, Melander, and Quinn 2015). Flores and Nooruddin (2012) argue unless countries have had previous democratic experience, elections must be delayed for institutional building to take place. Through a statistical model of economic recovery and conflict recurrence, Flores and Nooruddin (2012), warn that especially in new democracies, early elections hasten conflict recurrence. Therefore, delaying elections for some years to build democratic institutions might help prevent renewed violence (Flores and Nooruddin 2012; Joshi, Melander, and Quin 2015).

The acceptance or rejection of the electoral outcome is also a key moment in these types of provisions. This is can be achieved by establishing a level of trust between the parties and confidence in the electoral institutions. Joshi, Melander, and Quinn (2015) suggest that implementing accommodation provisions-such as interim electoral commissions to build consultative mechanisms and norms that increase the perception that political reforms will be effective (Lyons 2016) -as soon as possible after the signing of a PA is a highly effective strategy in getting a peace process started on the right path. Holding elections without such accommodation measures will raise fears of possible fraud, so these measures need to be “swift, verifiable, costly, facilitative, and non-disempowering” (Joshi, Melander, and Quinn 2015, 7). Lyons (2016) suggests that when collaborative institutions manage the electoral process during a transition, it generates greater confidence in the peace process. Furthermore, interim institutions can create confidence in the electoral process and ease the transformation of armed groups into political parties (Joshi, Melander, and Quinn 2015; Lyons 2006).

Power Sharing

Vandeginste and Sriram (2011) have suggested that power-sharing agreements are often essential incentives to induce post-agreement stability. However, power-sharing has also been linked to significant problems. It may provide political access to the state for individuals and groups who have committed violations of human rights and humanitarian laws during the armed conflict, which can limit transitional justice mechanisms (Vandeginste and Sriram 2011). Some scholars have found that political power-sharing has no effect on durable peace; only territorial and military provisions reduce the risk of recurring conflict because the latter entails high costs to the parties (Jarstad and Nilsson 2008). When analyzing whether these types of provisions are suitable for all kinds of divided societies, Ansorg, Haass and Strasheim (2013) have also questioned the role of power-sharing agreements within polarized ethnic groups and argue that power-sharing provisions may limit opposition.

The Importance of Trust

Many of the aspects mentioned above involve the principal challenge of peaceful cohabitation, confidence, and willingness among the parts involved in the implementation process. According to Mac Ginty, Joshi, and Lee (2019), the willingness of policymakers and other actors to implement peace provisions could be affected by the prospect for stable peace. Joshi and Quinn (2015) argue that this is especially relevant “early after the accord has been signed when anxiety levels are high, trust has yet to be established, and most times both sides remain armed and mobilized” (8). For ex-combatants, there are no guarantees that the government will keep its word once they have disarmed and demobilized (Joshi and Quinn 2015). Overcoming these challenges requires honest communication between the parties, which is difficult because both have clear incentives to misrepresent their true positions (Joshi and Quinn 2015). A critical moment for consolidating the confidence and willingness of actors is the context of the first democratic elections. According to Joshi, Melander and Quinn (2015), violence in this period often results from uncertainties regarding how opponents will rule if elected and “the inability of each side to convince the other that they will not exploit them if given the chance” (6).

Vandeginste and Sriram (2011) propose that power-sharing arrangements can promote cohabitation during PAI, which can, in turn, help prevent the reoccurrence of conflict and promote political and social reconciliation. For the authors this is a key issue because it allows for justifying a peace deal to the population (Vandeginste and Sriram 2011). Bekoe (2003) argues that mutual vulnerability works through the presence of sanctions for reneging the agreement, ensuring that parties compromise on implementation. She shows that when political accommodation coincides with suspicion of military or financial threats to the factions, implementation stalls. On the other hand, implementation advances in the presence of mutual vulnerability.

The Role of Regime and Government Ideology

Regime type and the ideology of the government overseeing implementation matter. Based on the Implementation of Pacts (IMPACT) dataset (which builds on the Terms of Peace Agreements Dataset and information from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program), Jarstad and Nilsson (2018) analyze different challenges democracies and autocracies are likely to face when implementing and deciding on provisions in a PA, using a large-N analysis based on data on power-sharing provisions in 83 PA in 40 intrastate armed conflicts between 1989 and 2004. The literature reviewed by the authors indicates that the incentive structure for autocrats to maintain and implement agreements is weaker as they are not dependent on voters, while former warring parties will face higher local costs in democratic regimes for not upholding agreements. The authors found that territorial pacts are also more often signed in democracies than in autocratic states and that it is much likelier that the parties will reach a political or military pact in an autocratic than in a democratic system (Jarstad and Nilsson 2018). This is because “the incentive structure in authoritarian regimes suggests that the previous warring actors will use any means to stay in power” (Jarstad and Nilsson 2018, 180). Thus, they argue that parties signing a peace agreement under a dictatorship may prefer political pacts to postpone elections and keep as much power as possible; at the same time, in democratic regimes, actors will be less reluctant to permanently hand over power to local elites through territorial pacts (Jarstad and Nilsson 2018).

Regarding implementation, Jarstad and Nilsson (2018) found that 62% of PA provisions were implemented in democracies between 1989 and 2004, whereas 67 % were in autocracies, which means that there is no significant difference between the two types of regimes. The authors suggest that this could happen because even though the incentives for signing agreements differ between regime types, the conditions for their implementation may be similar. In other words, after a civil war or armed conflict the security situation is usually fragile, infrastructure is often damaged or destroyed, and unemployment tends to be high, which puts a lot of stress on any government (Jarstad and Nilsson 2018).2

In addition to regime type, government political preferences and ideology are also relevant for implementation. Specifically, policy continuity or change of political authorities leading a country from negotiation to implementation is a crucial issue and illustrates how PA implementation is exposed to the vagaries of political and electoral processes. Chakma (2020), for example, has asked why government turnover (measured by leader and/or ideological turnover) reduces the implementation of peace agreements in some countries but not in others. On the one hand, insider leader turnover (when leadership changes within the same governing coalition) facilitates the implementation of peace agreements because insider leaders are familiar with the policies of the previous leadership (Chakma 2020). On the other hand, outsider leader turnover (when a new governing coalition comes to power) hinders the implementation of a peace agreement because outsider leaders play the role of “shadow veto players” (Chakma 2020, 1). One reason is that outsider leaders usually do not have enough information about the peace process, making it harder for them to decide on relevant aspects of the implementation process or not agree with the PA (Chakma 2020).

In terms of ideological turnover, new governments tend to be reluctant to implement peace agreements (or any policy) attributed to their predecessors, particularly when there is an ideological turnover (Chakma 2020). Generally speaking, supporters of left-wing parties are more “pacifist” and willing to punish leaders who take a belligerent stance, whereas a right-wing electoral base rewards aggressive policies (Chakma 2020). According to Chakma (2020), scholars have overlooked several plausible explanations in explaining PA implementation, including the level of influence of leaders, the degree of outsider leader turnover, the early outsider leader turnover effect, the composition of the government, and ideological turnover on the left-right spectrum.

b. International Factors

Literature on peace implementations has also mainly focused on the international context in which implementation takes place. Various scholars have pointed out the importance and relevance of international interest and financial commitment or aid. International dimensions include political support (for example, via multi-country groups of “friends” or supporters or by the United Nations) and resources to undergird crucial post-agreement tasks related to humanitarian attention and physical reconstruction. Hauenstein and Joshi (2020), for instance, suggest that international parties can induce cooperation between armed actors by imposing costs for non-compliance, overcoming resource constraints, and bringing regional, international, and local actors together in implementation.

Local ownership: short-term vs. long-term

Perry (2008) hints at a significant dilemma by posing the question of how post-conflict peace-building initiatives can “most effectively be supported by the international community, to ensure a balance between ownership and expediency” (50). Perry (2008) stresses the need for long-term action rather than short-term limited engagement. Lyons (2016) also argues that, without such support, implementation is prone to failure due to the international community’s role in monitoring and assisting so that the agreement is implemented as signed.

Geo-Politics and its Implications

One factor affecting the role of international actors is their sustained commitment and interest. Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens (2002) argue that the strategic importance of a country undergoing transition opens or closes windows of opportunity and that while intense international commitment does not guarantee success, a lack of commitment can virtually guarantee its failure. On the contrary, when there is stronger international interest, commitment towards implementation is likely to be higher, and resources are more likely to be made available to aid the process (Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002).

Joshi and Quinn (2015) argue that a donor’s role in implementation should also be tied to positive engagement and continued implementation progress. Emmanuel and Rothchild (2007) also suggest that significant and sustained post-conflict aid provided by donors reduces the likelihood of a return to civil war. Hauenstein and Joshi (2020) argue that regional and international organizations can use their peacebuilding experience to improve implementation “by offering security guarantees; monitoring compliance with an agreement; deploying peacekeepers, or sanctioning individuals or governments” (1).

The UN and Peacekeeping Forces

One principal actor in the international community in this regard is the United Nations (UN). Bekoe (2003) shows that the role of the UN in activities such as demobilization, civil administration, political reform, and electoral monitoring are key to peace implementation. Collier, Hoeffler, and Söderbom (2008), “find evidence that UN peacekeeping expenditures significantly reduce the risk of renewed war” (1). Hauenstein and Joshi (2020) suggest that although some researchers consider UN resolutions unhelpful, they can help improve PA implementation due to the commitment of the UN Security Council. Therefore, these types of resolutions show broad support for a PA but can also “shame parties who do not comply with the agreement, [or] deploy and coordinate resources” (Hauenstein and Joshi 2020, 1). This is evident in the possibility that the UN Security Council will impose, or threaten to impose, significant material costs on parties that obstruct implementation (Hauenstein and Joshi 2020).

One recurrent factor related to international actors is the deployment of peacekeeping forces. Jarstad and Nilsson (2008), Lyons (2016) , and Mac Ginty, Joshi, and Lee (2019) have shown that peacekeeping forces increase the prospects and help overcome security dilemmas for peace following a settlement by reducing uncertainty. It has also been argued that UN forces may be more neutral than regional peacekeepers. Yet certain studies have found that peacekeeping forces may deter implementation in some cases (Mac Ginty, Joshi, and Lee 2019).

Neighboring States

Neighboring states, another key factor, can be helpful or problematic depending on their commitment and resources. Joshi and Quinn (2015) have shown how highly committed, well-resourced, and unfriendly neighbors shape a challenging environment, while a few uncommitted and poorly resourced unfriendly neighbors have little effect on implementation. On the other hand, neighbors friendly to the peace process can exert positive influence, directly and indirectly, by denying spoilers resources or refuge (Joshi and Quinn 2015).

External Shocks, Public Health, and Wars

Peace agreements compete for resources and support with other policy priorities. This becomes especially clear with external shocks, such as public health threats (the Covid-19 pandemic) or global crises and wars, which can become international and domestic game-changers in terms of financial and political support (Joshi et al. 2020a).

Economic Aid and International Donors

The role of international aid and donors is key to sustaining peace initiatives in a post-conflict scenario. There exists a well-established debate on aid effectiveness in conflict scenarios, its importance, and the often-conflicting consequences international aid and donors can bring to a post-conflict setting (Kozul-Wright and Fortunato 2011; Crocker, Hampson and Aall 2005). Scholars have shown mixed evidence: donor aid can either reinforce the social contract between state and society in war-to-peace transitions or undermine it (Kozul-Wright and Fortunato 2011). For example, Woodward (2002) acknowledges that the economic impact of international peace missions sometimes runs contrary to the aims of self-government and political sustainability. More precisely, donors’ decisions about whom to assist or what projects to fund will likely have a lasting political impact on the country (Woodward 2002). Because of this, economic aid and assistance should always consider the local impact it can generate.

For many years, there has been wide criticism of international interventions focused on addressing the effects of conflicts rather than the underlying causes, which in many cases include social and economic inequalities and scarcity of resources (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018). Traditionally, international aid has been considered technical rather than political, isolated from local socio-economic traditions, legacies, and pre-conflict practices. Nevertheless, Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel (2018) argue that while humanitarian agencies now “call for a localization of responses, the international donor community keeps selecting their local partners and perspectives carefully, ensuring the chosen local perspective concurs with international agendas” (146).

Recent literature has sought to understand the conflict between local and international understandings of peace (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018). This literature invites us to consider historical, political, and relational dimensions when economic provisions are implemented that call for international aid (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018). A focus on the local level and the international intervention in economic provisions may enable scholars and policy makers “to better grasp the processes of post-conflict economy formations, and what is required to steer them towards peace economies that can support sustainable peacebuilding efforts” (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018, 147). Woodward (2002) argues that international aid should always consider the need for broad-based impact assessments in the short and long term, have an early emphasis on employment, which is critical to redirecting behavior and encouraging support for the PA, and invest in building institutional and social capital to ensure good governance. Berdal and Wennmann (2013) argue that what may look ideal in terms of economic development from an international perspective may prove politically destabilizing and conflict-generating in the short term. For example, the authors suggest that while robust institutions at the national and local levels normally provide the backbone of resource management, in the short term, it may be necessary to postpone the principles of “good governance” as institution-building policies may destabilize peace negotiations or the initial implementation phase (Berdal and Wennmann 2013).

c. Economic Factors

In many ways, economic capabilities shape and limit political and social aspirations of transformation via peace agreements. Therefore, financial resources for peacebuilding, which tend to be limited, are a principal factor in successful PA implementation. Governments and policymakers need to maximize existing resources and define priorities. Additionally, Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel (2018) suggest that disregarding socio-economic aspects leaves a significant vacuum in our understanding of peace, its sustainability, and the formation of post-conflict economies. When referring to the economic factors of peacebuilding, scholars argue that complex tensions arise between the pursuit of economic priorities, the requirements of peacebuilding, and political stability at the local level (Berdal and Wennmann 2013). Nevertheless, carefully designed policies or provisions aimed at economic recovery and the transformation of political economies of violence are not only crucial but can also provide incentives for cooperation and peaceful behavior among warring parties (Berdal and Wennmann 2013). In this section, we explore economic factors affecting PAI from the local level to international involvement.

Economic provisions and resource allocation

Scholars have shown that armed fights deepen socio-economic inequalities, which, in fact, breed and extend conflict (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018). In addition, economic claims and motivations are frequently part of violent eruptions, hence their importance when implementing a PA; implementation cannot be sustained if economic issues are not addressed (Costantini 2012). One argument supporting this claim is that in “post-conflict areas, the economy contributes to creating a new vision of society which convinces the parties that it is indeed worthwhile to stop fighting and benefit from the economic opportunities of peace” (Wennmann 2009, 44). This aspect is crucial in understanding the ways in which socio-economic factors condition how people live their lives; thus, it is important to highlight that post-conflict economies “are politically designed and shaped by a multitude of actors who struggle over power, representation and a new social order globally, regionally and locally” (Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel 2018, 145).

Within the academic literature various scholars have shown the links between insecurity, violence and underdevelopment or poverty (Collier et al.,2003). One of the greatest exponents of this are Collier et al. (2003) who argue that war means development in reverse. This thesis defended by international institutions argues that interstate conflicts have harmful effects on economic development, a phenomenon the authors refer to as a "conflict trap"(Collier et al. 2003). In that vein, post-conflict societies face two key challenges: economic recovery and the risk of a recurring conflict (Collier, Hoeffler, and Söderbom 2008). These two challenges are intertwined, because economic development substantially can reduce risks of renewed violence in the long-term (Collier, Hoeffler, and Söderbom 2008).

Systematic analysis of whether the inclusion of economic provisions in PAs fosters sustainable peacebuilding, reducing the likelihood of conflict recurrence, is limited (Wennmann 2009). This is problematic because scholars have demonstrated that PAI frequently depends on economic factors, such as rapid economic revival in countries affected by conflict to generate confidence in a PA, adequate funding to implement key aspects or provisions, and sufficient funding to enable the establishment of government institutions and the transition to a sustainable peace-time economy (Woodward 2002). According to Wennmann (2009), economic issues and provisions should be included in PAs to instrumentalize the economy for peacebuilding. The potential of an economic focus in PAI “lies in creating joint futures, managing expectations in the economy, reducing spoiling and providing peace dividends for the parties” (Wennmann 2009, 56). Moreover, economic provisions as part of institutional and political transformation may increase the predictability of economic interaction and resource sharing in a post-conflict scenario (Wennmann 2009). However, a review of cases by Wennmann (2009) shows that economic provisions only work if parties allow their inclusion; if they are forced in the wrong circumstances, this can lead to PA failure because parties may start to lose trust in the agreement.

Regarding specific policies and provisions, the economic dimension of peacebuilding may involve short-term demands for security and stability. Therefore, it “may require some form of engagement with informal often illiberal power structures as a necessary step in a longer process designed to wean an economy away from violence and crime and towards peaceful legitimate economic activity” (Berdal and Wennmann 2013, 9). For this reason, policymakers and scholars need to analyze the peacebuilding environment to grasp the underlying political economy of a conflict zone instead of labelling or minimizing complex problems that have served to perpetuate or stimulate renewed violence (Berdal and Wennmann 2013).

Another key issue concerning the economic factors shaping PAI is resource allocation. It implies a division and transfer of power and resources among the parties in conflict at political, economic, and social levels (Costantini 2012). Resource allocation, therefore, can be seen as a way to solve issues in PAI or as a cause of tension leading to distrust (Costantini 2012). The process depends on changing domestic and international political dynamics identified as important determinants of which policies or provisions are implemented (James 2021; see also section on International factors). Collier, Hoeffler and Söderbom (2008) find there is a relationship between the severity of post-conflict risks and the level of income at the end of the conflict, therefore “resources per capita should be approximately inversely proportional to the level of income in the post-conflict country” (1).

The Role of the Private Sector

A principal factor that can improve economic conditions for PAI is engaging the private sector and business communities (Costantini 2012). From the start, the private sector is affected by conflict (Miklian et al. 2021; Rettberg 2003; Working Through Violence Research Team 2021). In the Colombian case, Rettberg (2003) demonstrates that the armed conflict placed a considerable burden on the Colombian private sector due to climbing rates of capital flight, the destruction of infrastructure (such as oil infrastructure), kidnappings and extortion of employees, and the growing tax burden to support the war effort. During the pandemic, the socio-political conditions exacerbated the threat of extortion and violence against firms (Working Through Violence Research Team 2021). The private sector accordingly plays a significant role in PA and PAI. Rettberg (2019) has proposed that business responses to conflict have three main motivations: the need for peace so business can operate correctly; the willingness of business to support a PA; and the anticipation of renewed investment, profit, and growth. A firm commitment to peace by the private sector can affect PAI because its support can broaden the impact, depth, and course of a peaceful transformation (Rettberg 2019). During the pandemic, the Working Through Violence Research Team (2021) argued that businesses can be seen as problem-solvers and peacemakers during these types of crises or as harmful actors. Using a survey of 78,000 people in seven cities around the world, the authors found that in areas that deteriorated in terms of public safety, extortion, and corruption, citizens said businesses were part of the reason they were struggling; in areas that did well, citizens credited businesses with their shared success (Working Through Violence Research Team 2021).

d. Security or Military Reform

Another factor that is central to PAI is security or military reform. Most authors acknowledge that these types of provisions, which range from smaller sub-goals to more ambitious policies, are essential to a successful transition from war to peace. Joshi, Quinn, and Regan (2015) have identified up to eight provisions: disarmament, demobilization, reintegration, military reform, police reform, ceasefire, paramilitary groups, and withdrawal of troops. Although these seem dispersed, scholars have found that many such provisions are typically negotiated as a cluster and their implementation is highly interdependent (Joshi, Quinn, and Regan 2015).

Some authors point out that a security-sector reform that includes police and judicial reforms is key to providing basic protections for combatants and the civilian population (Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). Additionally, military pacts or reforms involve higher logistical, economic, and immaterial costs than political pacts (Hartzell and Hoddie 2003). These can include the integration of commanders and/or combatants into national armed forces, which is a provision that is time-consuming and economically costly for both parties (Hartzell and Hoddie 2003). These types of military pacts or reforms seek that former adversaries work together and share military tactics and strategies. Jarstad and Nilsson (2008) argue that when parties engage in such costly concessions, they demonstrate commitment to the process.

Another crucial provision to guarantee a peaceful transition is demobilization. Stedman (2001) and Joshi, Melander, and Quinn (2015) argue that demobilization is one of the most significant provisions during PAI because it can hinge on the willingness of combatants to return to conflict (Stedman 2001). Granting amnesty shows the parties’ disposition to live together without vengeance (Joshi, Melander, and Quinn 2015). The demobilization process is less likely to occur without amnesty due to the reluctance of combatants to undergo prosecution or repression and must go hand in hand with the political transformations of former military organizations.

In an opposing view, Vandeginste and Sriram (2011) warn that implementing such provisions in volatile contexts can be a sensitive issue, meaning they might be a potential risk factor. Kurtenbach and Ansorg (2020) , for example, suggest that security-sector reform may activate spoilers and constitute a risk of conflict resumption. Short of complete security-sector overhauls, implementation processes may therefore attempt careful and cautious combinations of provisions, including amnesties, the release of prisoners, large-scale disarmament, and the assurance of security for ex-combatants for demobilization to happen (Joshi, Melander, and Quinn 2015; Stedman 2001).

Other Armed Third Parties or Spoilers

Stedman (1997) pioneered the concept of spoilers in peace processes, referring to leaders, parties, or groups “who believe that peace emerging from negotiations threatens their power, worldview, and interests, and use violence to undermine attempts to achieve it” (5). This concept has gained importance both in the academic literature and in public policy (Nilsson and Kovacs 2010). However, Nilsson and Kovacs (2010), have argued the concept has been stretched beyond its original meaning leading to ambiguities in its applicability. Because of that, they suggest that spoilers should be referred to as “parties to the armed conflict who use violence or other means to shape or destroy the peace process and in doing so jeopardize the peace efforts” (623).

Joshi and Quinn (2015) have followed up by arguing that a viable implementation process should include rebel factions and splinter groups that initially decided to remain outside the peace process or were not included. The isolationist and obstructionist behavior of these actors can become costly for the process, while the benefits of formally joining the peace process are promising (Joshi and Quinn 2015; Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002). Joshi and Quinn (2015) suggest that outside factions that were not part of the PA may decide to join the process if they see that implementation is viable and fear becoming isolated. Through a statistical analysis, Joshi, Quinn, and Regan (2015) show that “high levels of implementation can reduce conflicts between the governments and non-signatory groups” (560). In brief, the effects of these actors on PAI will depend on their commitment and whether they have assigned or not resources to torpedo it (Stedman, Rothchild, and Cousens 2002).

Post-War Economies, Illicit Economies, and Land

As soon as a PA is reached, uncertainty arises about the transformation of post-war and illicit economies. In most cases, armed or rebel groups rely on illicit economies (including trade in drugs and natural resources) for their armed efforts. Due to the possibility of a power vacuum that allows illicit economies to continue under different armed organizations, drug cartels, or local elites, it is essential for implementers to address an economic transition. As Kurtenbach and Rettberg (2018) argue, “the transition out of war is a complex endeavor, interrelated in many cases with other transformations such as changes in the political regime and the economy” (1). Thus, many transitional contexts are marked by a steady and ongoing reconfiguration of criminal and illegal groups and practices. A focus on the transformation of post-war economies is a key factor during PAI, related to institutional weakness and the influence of illicit actors. Persistently low levels of state capacity regarding the regulation of violence and the provision of public services, the ongoing control of illicit flows of resources and weapons by armed actors, and changing patterns of violence are three of the most important factors to take into consideration for analyzing post-war economies (Kurtenbach and Rettberg 2018).

According to Massé and Le Billon (2017) , post-war transitions involve a change in the logic of conflict and violence, “understood as a shift from politically motivated violence to criminal violence driven by economic motives” (8). In this scenario, weak resource governance not only accounts for the onset of violence but also for the resilience of crime, as illicit markets remain a challenge once formal fighting has ceased (Kurtenbach and Rettberg 2018). Massé and Le Billon (2017) identify a risk of renewed violence and criminalization in resource-rich post-war transition contexts. Some of the provisions intended to minimize the risks of post-war and illicit economies are the prolongation of commodity sanctions, the effective demobilization of ex-combatants, policing of resources areas, the formalization and verification of resource extraction actors and activities, and the promotion of foreign investment in large-scale extractive projects (Massé and Le Billon 2017).

Violence Transformation (Post-War Violence)

Compounding many of the factors discussed so far is the fact that violence may continue even when a peace agreement is signed (Kurtenbach and Rettberg 2020) and thus influence PAI. However, post-war violence does not affect all communities equally; while some remain in conflict, others escape its perpetuation due to implementation (Van Baalen and Höglund 2019; Weintraub et al. 2021). In addition, war legacies can shape the dynamics of post-war periods (Kurtenbach and Rettberg 2020), reflecting discrepancies between national and local levels. In cases “where local conflicts were heavily exploited by armed actors there is a higher probability for war to have lasting negative effects on local conflict dynamics” (Van Baalen and Höglund 2019, 1171). Ljungkvist and Jarstad (2021) have also pointed to differences between urban and rural violence in post-war periods due to the fact that implementation, institutional presence, and resources take longer to arrive to some regions, causing profound effects.

One noteworthy explanation for post-war violence is explored by Van Baalen and Höglund (2019) . The authors argue that in communities where wartime mobilization at the local level is based on the formation of alliances between armed groups and local elites, the likelihood of post-war violence is higher. This type of indirect mobilization by local elites can enable them to employ violence at will in the post-war period. Inversely, in communities where armed groups generate civilian support based on grassroots backing of the group’s political objectives, the likelihood of post-war violence may be lower. This direct mobilization allows armed groups to rally support by promoting local endorsement of their political objectives and commitment towards a PA that limits post-wartime violence (Van Baalen and Höglund 2019).

e. Civil Society and Popular Support

Civil society has long been a central actor in development and conflict studies. However, its specific role in negotiations and PAI is more recent. For instance, Mac Ginty and Richmond (2013) identify a “local turn” in peacebuilding, acknowledging the importance of local communities, civil society, and popular support in PAI. As argued by Ljungkvist and Jarstad (2021) , local ownership is defined as an engagement with local communities to embed peacebuilding locally, tailor it to local needs and cultural expectations, produce an opportunity for emancipation through attentiveness to local particularism and support of local agency. It has emerged as a key prescription for obtaining legitimate and authentic peacebuilding. Engagement with local communities and civil society is seen as a way of embedding implementation locally and building it around local needs and cultural expectations (Ljungkvist and Jarstad 2021).

Some scholars argue that civil-society inclusion in a PA leads to more solid implementation because it increases accountability and legitimacy (Paffenholz 2010; Hauenstein and Joshi 2020). According to Binningsbo et al. (2018) , popular support is key to PAI, and victims of the conflict should constantly evaluate the process. Scholars have also shown the negative effects the lack of popular support can have on a peace process and its implementation. The case of Guatemala, as analyzed by Stanley and Holiday (2002) , shows how voters’ rejection of a constitutional reform package had a profound impact on the implementation provisions and international donors’ aid, confidence, and support. Others are more skeptical about the value of inclusion and point to the risk of agenda overload and unfulfilled expectations (Bramsen 2022).

Women’s Participation and Gender Issues

Discussion of inclusion is especially relevant for women’s participation and gender issues. Krause and Olsson (2021) argue that women’s inclusion can be essential to increase legitimacy and social capital and improve the chance of durable peace. Women’s meaningful inclusion is relevant for the quality of peace, while their exclusion from peace negotiations undermines its durability (Krause and Olsson 2021; Oettler 2019). This aspect is evident when analyzing peace processes where gender provisions have been only added, and actual changes are harder to be seen (Krause and Olsson 2021). Joshi et al. (2020b) also argue that the mere inclusion of gender provisions in an agreement is ineffective in improving gender equality or achieving durable peace. Based on a statistical analysis of 205 civil war terminations in 69 countries since 1989, Joshi and Olsson (2021) propose that a conflict terminated through the negotiation and implementation of a PA significantly improves women’s political rights-when it includes women’s rights provisions-in the post-war period, compared to other types of conflict termination.

Evidence presented by Gindele et al. (2018) shows that creating a more peaceful society for men through PAI does not automatically mean the creation of a more peaceful situation for women. The authors also demonstrate that failing women and gender stipulations can discourage women’s organizations from contributing towards implementation where they are pivotal agents for victims and local communities. At the same time, while gender provisions can be one tool for including women’s interests, research has yet to show their role in actual advancements in gender equality post-war (Krause and Olsson 2021). This is exemplified by feminist unease with the terms on which inclusion is offered in PAI. Bell and O’Rourke (2007) argue that while women are increasingly included in PAI mechanisms and discussions, there is little scope to reconsider and reshape the end goals of a PA with a gender lens.

f. Transitional Justice

Many recent peace agreements include transitional justice (TJ) provisions, defined as judicial and extrajudicial arrangements that facilitate and allow a transition from a situation of war to one of peace (Rettberg 2005). This kind of provision seeks to clarify the identities and destinies of victims and perpetrators, establish the facts related to human rights violations in situations of armed conflict, and design how society will address the crimes perpetrated and the need for reparation (Rettberg 2005). TJ is transitional to the extent that it seeks to build bridges between different regimes and political moments to establish new political and judicial orders (Rettberg 2005). Sriram (2017) perceives six main TJ initiatives discussed by policymakers and scholars: trials, commissions of inquiry or truth commissions, amnesties, vetting, restorative justice, and traditional justice. TJ can affect PAI since it exposes human rights violations and those responsible for them, may lead to political polarization, and requires significant resources (for the operation of TJ institutions and for the reparation of victims, for example).

Sriram (2017) affirms that TJ provisions or policies are expected to help promote peace in conflict-affected countries through measures that rely upon legal processes such as trials, amnesties, or truth commissions. Policymakers and advocates often claim that restoring the rule of law, legally reforming institutions of governance, and creating transitional justice mechanisms will help reinforce nascent peace processes (Sriram 2017). However, a consensus now exists in the field of study that TJ has privileged “the state and the individual rather than the community and the group; the legal and technocratic rather than the political and contextual; and international rules and standards rather than cultural norms and local practices” (Baker and Obradovic-Wochnik 2016b; Sharp 2013).3 Through case studies in different countries and a literature review, Sriram (2017) shows that the evidence of the rule of law in promoting peace through TJ is mixed and that, in many cases, the relationship between rule of law and legalized policies and peace building has the potential to be negative.

One possible explanation for the current criticism of traditional TJ, posed by Baker and Obradovic-Wochnik (2016a) , is that when trying to locate the nexus between peace and TJ, scholars need to identify where theory must be produced to facilitate a peaceful outcome. This shows the imbalances between local definitions of “justice” and “peace” and the definitions held by international donors and peacebuilders (Baker and Obradovic-Wochnik 2016a). The authors find it surprising how “local and everyday dynamics are dismissed as sources of peace and justice, or potential avenues of addressing the past” (Baker and Obradovic-Wochnik 2016a, 1). Therefore, they argue that a hybrid model using conventional and local practices of peacebuilding and TJ can respond to how local communities embrace a legal transition from conflict to peace (Baker and Obradovic-Wochnik 2016a; Sharp 2013) .

Another explanation is the feminist critique that argues that TJ legal standards have tended to be exclusionary for women, producing thus gender imbalances (Bell and O’Rourke 2007). Bell and O’Rourke (2007) argue that women suffer disproportionately from armed conflict and play a key role in post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation because they often predominate as household heads in post-conflict societies. Feminist interventions highlight the need to secure effective feminist engagement with the newly reformed state through a dynamic transition that acknowledges, for example, the impact of transition on the private sphere, family and reproduction issues, changes to and reflections on gender roles, and a specific attention to how violence against women often changes in form rather than ending (Bell and O’Rourke 2007).

Truth Commissions

One principal mechanism of TJ consists of truth commissions, defined as official investigative bodies created to research, document, and report on human rights abuses within a country over a period (Dancy, Kim, and Wiebelhaus-Brahm 2010). Truth commissions are normally embedded within larger processes that include other forms of TJ depending on the specific provisions in each case. For example, sometimes truth commissions are created before trials, as in Argentina, or are established alongside trials, as in Sierra Leone (Dancy, Kim, and Wiebelhaus-Brahm 2010). Another mechanism identified by Dancy, Kim, and Wiebelhaus-Brahm (2010) is the presence of unofficial truth projects normally occurring at the grassroots level or carried out by civil society organizations. This type of mechanism helps address broader historical situations that laws generally fail to address (Castillejo-Cuéllar 2014). In other words, to grasp the multiple dimensions of violence, collective legal languages fail to render intelligible the dimensions of violence that are the root of the conflict (Castillejo-Cuéllar 2014). This responds to the initial argument on apprehending local initiatives when implementing TJ provisions.

In a similar vein, Rudling (2019) argues that within TJ mechanisms, victims are often perceived as a “single group, regardless of glaring contrasts amongst them insofar as background, capabilities, and transitional justice needs, interests, and expectations” (422). This homogenization of victims has political, moral, and legal consequences that condition TJ mechanisms (Rudling 2019). Therefore, Rudling (2019) suggests that a genuine incorporation of victims into TJ depends on critically assessing the beliefs behind the construction of TJ instruments and policies such as truth commissions. This is key for locally identifying victims’ needs, interests, expectations, and conditions to give them appropriate attention and assistance.

Reparations

Another relevant TJ mechanism is reparations. Reparations programs occupy a special place in TJ mechanisms because, for some victims, reparations are the most tangible (and sometimes the only) way the state can remedy the harms and grievances suffered during the armed conflict (de Greiff 2006). This mechanism raises the question of who should receive reparations and how to distribute them. Most reparations policies have concentrated in a limited way on cataloging civil and political rights, leaving the violation of other rights largely unrepaired (de Greiff 2006). De Greiff (2006) argues that “frequently decisions concerning the catalog of rights whose violation triggers reparations benefits have been made in a way that excludes from the programs those who have been traditionally marginalized, including women and some minority groups” (7). Bell and O’Rourke (2007) have also highlighted a systematic exclusion of women from the process of designing reparations programs, including the definition of the violence to be repaired, criteria for defining beneficiaries of reparations, and benefits given to victims. In theory and in practice, one of the least studied aspects of programs of reparation that can help explore the debate of reparations is financing (Segovia 2006). Mobilizing resources-both domestic and foreign-is a political issue and is identified as one of the most challenging tasks when implementing TJ mechanisms (Segovia 2006). Segovia (2006) argues that to ensure the implementation of reparations programs, a balance of political forces that favor such programs is necessary.

Concluding Remarks

In this working paper, we offered a literature review on the most relevant factors influencing peace agreement implementation (PAI). One of our main arguments has been that the period following the signing of a PA is marked by uncertainty, intense changes, and the political and social tensions this entails. Using a variety of sources and examples to illustrate the challenges of peace implementations, we propose that political and institutional reform, international factors, economic factors, security/military reform, civil society and popular support, and transitional justice mechanisms mark the broader landscape in which PAI takes place.

We believe there is room for further research. For example, a stronger academic focus is needed on topics such as people’s perception of implementation, environmental issues that are likely to become more important, the growing possibility of a lack of funding and attention to PAI from international organizations or donors, and issues related to the scope and style of verifications of implementation in the long term. All these constitute new challenges that scholars and policymakers will face in the coming years. We hope this paper will serve scholars as input for further research and debate on making PAI more effective and conducive to sustainable peace.