Introduction

Health is one of the core aspects for development and global sustainability, therefore, it is included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN Agenda 2030 (2015). Development models implemented throughout the 20th century have been characterised by exploitation, competition and unsustainability, which generates significant economic profit margins in exchange for unhealthy and impoverished communities and environments. The impacts of these extractive models include Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), accelerated climate change, or the overwhelming pollution of all vital resources 1. The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations have been seeking strategies to curb all these negative impacts that have been threatening life on the planet. For the last three decades, they have recognised the effect of people’s Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), promoted the adoption of decisions and political actions to be able to counteract them from the different multinational and thematic political arenas 2. Recognising1 the influence of SDOH on the quality of life of communities and individuals has led to the promotion of interventions in all settings, creating strategies such as healthy municipalities, healthy organisations, and healthy schools, among others.

At universities, this approach was initiated in the 1990s and it became the worldwide movement of Health Promoting Universities or Healthy Universities. Ibero-America is one of the regions of the world with great dynamism and commitment to incorporate institutions and their campuses into Health Promotion. The most significant samples of the cultural, social and economic diversity of the context in which they are located converge at the universities, where the professionals who take on the leadership of the sectors of society are trained, and where a large part of the knowledge is produced in the different disciplines and sciences that leverage technological, social, economic, political, environmental and cultural advances 3. One of the challenges they are currently facing is how to contribute to the generation of healthy environments, as the world is not finding the necessary answers to improve living conditions and situations of people.

However, although experiences have been accumulating in universities with regards to many of these SDOHs (i.e., as part of strategies for university welfare, human development, sustainable campuses, the university environment in general, among others), there is no clear route for action, nor is there an epistemological, theoretical or methodological framework for the consolidation of healthy environments. Although understandable, given the novelty of the subject matter and the complexity involved, these are key factors in anchoring these strategies in all university structures.

Recognising the current relevance of environments and taking into account the dimensions that are also involved in health, it is necessary to build a comprehensive and integrated vision of health from the perspective of all stakeholders, going beyond the biomedical approach and incorporating positive health into policies and their instrumental chain (plans, programmes and projects), which translates into articulated, systematised and hopefully institutionally regulated interventions and into applied or explanatory research that consolidates university campuses as true healthy environments and health educators with an impact on the surrounding territories.

By accepting the absence of reference frameworks for healthy universities, we start from the premise that this new approach, like any other that aims to transform realities in complex social contexts, must have a solid epistemological and theoretical foundation that support the interventions and research. Experiences shared at events held by cooperation networks of Ibero-American health-promoting universities over the last two decades, as well as published materials, highlight the urgency of collaborative work to overcome the weaknesses identified and to strengthen research and intervention in this field 4. Building frameworks will allow universities to better understand the meaning of incorporating health promotion into their mission frameworks, which will also result in greater strategies, resources and impact in all interventions formulated.

Objectives

To analyse the health paradigms that prevail in today’s university world and to specify the dimensions that define them in order to guide the Healthy Universities Interventions. To propose a comprehensive and integrated vision of health for the construction of healthy institutional environments.

Methodology

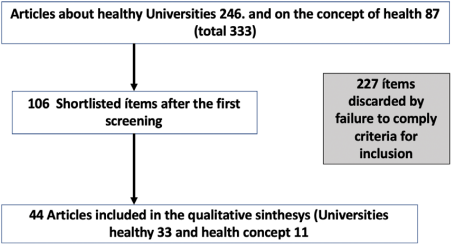

Using the PICO 5 strategy, which is widely used for systematic reviews in the field of health, two guiding questions were posed: What are the paradigms and dimensions of health present in healthy university actions? and, how can healthy university interventions be approached from a holistic perspective? The ideas, experiences and proposals contained in the selected documents were examined in regards to the area/problem which corresponds to health in the university context. With this strategy, the respective search log was built from the meta-search engine of the library of the Universidad del Valle. To make the study more rigorous, the PRISMA method (Figure 1) was used 6 and the databases consulted were: Dialnet, Scielo, Ebsco, Supplemental Index, DOAJ, Proquest, Academic Search Complete, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Medline, PubMed, ISI Web of science, Redalyc and Latindex. The time range of consultation was set between 2007 and 2019 because there is not much literature available yet due to the recent and underdeveloped nature of this subject. Articles related to university settings or to some of their stakeholders, which could be included in the health dimensions addressed, were collected. Regarding the health concept, the publication date was from 2002 to 2018. After saturating the field, complementary research was performed with the intention of increasing the scope of the study. The sifting of documents was done by the researchers, until the set of documents considered relevant to the objective was reached. For greater validity of the information collected, a test-retest was applied. The analysis of the selected documents was carried out with the help of a matrix we created that crossed the university stakeholders with the five dimensions of health. The reflections were guided by the interpretative perspective, following the principles of Grounded Theory.

Results

The review was oriented according to the stated objectives, therefore, the studies selected for qualitative analysis were 33 for the dimensions of health and 11 for the concept of health. A classification table was also created in Excel according to the categories of analysis: concept of health, physical, mental, social, spiritual and environmental dimensions. In this table the summaries, discussions and conclusions of each study were added for later cross-sectional reading and the respective qualitative analysis.

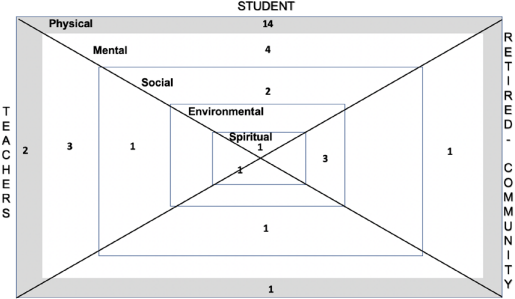

For the in-depth analysis of the selected studies, a matrix of stakeholders and dimensions in which each of the articles that met the review criteria were placed (Figure 2) was drawn up. The matrix reflects where most studies have been conducted, and which areas and agents have been least addressed so far, indicating the need for further academic development of health promotion in universities.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 2 Matrix of studies conducted according to stakeholders and dimensions.

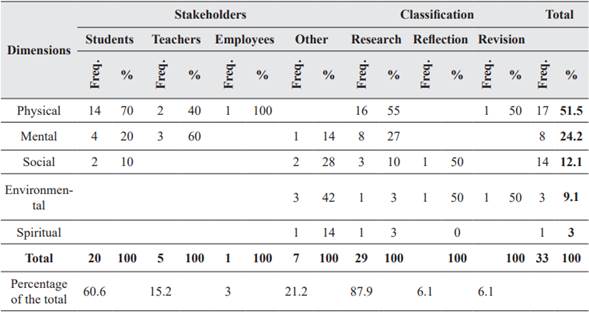

The majority of the 33 studies on the dimensions of health in university contexts (88%) (Table 1) are research studies; reviews and reflections are still scarce (6.1% each). Most of the studies in university contexts are located in the physical dimension (54.5%), followed by those that point to the mental dimension (24.2%). The social dimension (12.1%) is followed by the environmental dimension (9.1%) and finally the least explored dimension in university contexts corresponds to the spiritual dimension (3.0%).

Table 1 Classification of studies according to dimension, stakeholders and percentages.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Additionally, the selected studies mostly involve the student population of the universities (60.6%), followed by teachers or professors (15.2%). Then, we found the category of others, which includes the university community in general, the neighbouring community or pensioners (21%), highlighting that none were found with the pensioner population; finally, we found research with the university employees or workers population (3%).

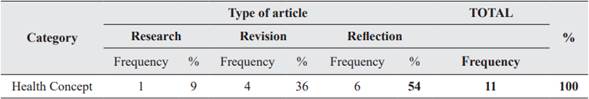

In the teaching force, the most studied dimension corresponds to the mental dimension with 60%, followed by the physical dimension with 40%. Regarding the student force, the physical dimension is the most explored with 70%, then the mental dimension with 20% and the social dimension with 10%. Neither of these two populations specifically addresses the environmental or spiritual dimensions. With regards to the concept of health in general (Table 2), the majority of studies are reflective studies (54.6%), followed by review studies (36.4%) and only one study (9%) categorised as research.

Discussion

The information selected through the reviewing process made it possible to analyse two areas that are considered key for healthy universities. The first one corresponds to the concept of health, seen from the present time, highlighting the different paradigms in retrospect that have been conducted throughout history, and generating a new conceptual approach. A second element corresponds to the dimensions of health, i.e., the areas where human beings interact and develop their lives and which directly or indirectly affect their notions and meanings of what is considered healthy, these dimensions are: physical, mental, social, environmental and spiritual.

Approaches to the contemporary concept of health

The concept of health goes beyond its relationship with illness, as stated by 7; in other words, it is not an exclusive matter of the medical field, and both individuals and communities are liable, therefore, they exercise rights and duties, and they also have the capacity to make their own decisions. The concept of health is directly linked to the cultural, social, environmental and historical context 8 in which it is analysed. The evolution of the conceptualisation of health has meant that it is now closer to concepts such as well-being, quality of life and happiness than to illness.

As a conceptual milestone, perhaps the most complete definition at the time (mid-20th century) was provided by the WHO, which considered health as a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, and not just the absence of disease2.

Although this concept has been subjected to worldwide validation, with much criticism of its rationale, there is no other official concept to guide interventions in this area. Health has been the subject of study and analysis from different disciplines and sciences such as: Anthropology 9,7, Philosophy10, Law11, Environmental Sciences12, in general Social Sciences13Human Sciences14,15, and Health Sciences and Disciplines16.

The review of all these analyses allows us to conclude that in the different cultures, moments and perspectives there is a convergence in the use of terms whose meaning is associated with the words: balance, harmony, equity, while illness corresponds to the opposite meaning of these words, as pointed out by 9.

Recognising that there is health beyond the absence of illness has led to other constructions, among which the notion of positive health stands out. Many authors have dealt with this notion since the emergence of health promotion and disease prevention as a main topic for policies, and positive health also identifies various dimensions such as: social, physical, spiritual, mental (intelectual-emotional) and environmental health.

It is currently observed that, despite the evolutions of scientific, technological and cultural progress, the different visions that have historically been held persist, either totally or partially in any definition of health that is formulated. Health is on a continuum of interactions that blur together and amalgamate depending on variables such as life cycles, the environments in which life unfolds, and ideas and beliefs about the transpersonal or spiritual aspects 17.

Although in the evolution of the concept there is talk of dimensions in various perspectives, it is in the WHO concept where the dimensions are specified: physical, mental and social, implying that life unfolds in these three worlds, and the health-illness relationship is mediated by these. From the holistic approach to health, the dimensions that can be considered for both knowledge development and interventions in the case of university settings are: physical, mental, social, environmental and spiritual.

In view of the above, and based on 17, the following definition of health is proposed: It is a relative moment, a product of all the dynamic interactions that occur in the physical, mental, social, environmental and spiritual dimensions that originates in the individual and their surroundings, which are socially distributed, conditioning their biology and life relationships.

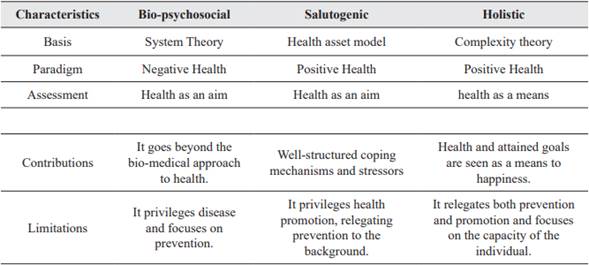

We highlight the following health models that go beyond the biomedical model:

From these models (Table 3) we conclude that health currently means a great responsibility of the individual towards its different dimensions and determinants, in contrast to previous historical moments in which more responsibility was attributed to the State and Organisations, given the close relationship with the collective’s well-being. These models also contain valuable insights for the design and implementation of policies and plans for building healthy environments and communities. Although all three models lack a solid epistemological and theoretical basis, they have gradually provided a holistic perspective of the human being that previous models lacked.

University physical health

In today’s world, the physical dimension of health is more important than ever, due to the worrying increase in non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs), which have set off alarm bells in different countries. Physical activity has been recognised as a high-impact public health strategy, and evidence supports this with countless research studies since the mid20th century. On the other hand, evidence shows that aspects such as unhealthy diets, consumption of substances such as tobacco or alcohol, physical inactivity and stress, among others, are associated with NCDs, which in turn are generators of high externalities, but as pointed out by 18 they are modifiable through the adoption of healthy lifestyles. The positive impact of health promotion on reducing morbidity and mortality from these causes is also well known.

Thus, university physical health is understood as the institutional studies and interventions that address aspects associated with the lifestyles and cultural or social practices of its stakeholders that have a potential effect on the human organism. The selected studies (Table 1) converge on a strong concern for the physical health of stakeholders, mainly students 19.

In general, risk factors for NCDs are observed in all university populations 20-22, such as inadequate dietary habits due to excess fat, sodium, carbohydrates and sugars or abnormal eating times, low consumption of fruit and vegetables 23-25, low frequency of physical activity, high rates of obesity 26,27, among others. High levels of psychoactive substance use, sleep disorders and unhealthy sexual practices are also observed among students 28,29.

Although all stakeholders found low rates of frequent physical activity 18,30,31 in student research, it is striking that despite the interest and interventions of universities to promote these practices, approximately 30% do it frequently, the rest do not do it or do it sporadically. Both Latin American and European studies agree on the physical health risk factors found in university populations 32; although the contexts are very different, the habits or lifestyles characteristics share common elements 33,34.

University mental health

Mental health has been assessed by the WHO as fundamental to the well-being and advancement of societies and individuals. This is not only due to the high costs of health services in all countries of caring for mental illnesses, but also to the high impact on the individual, family, community and social spheres 35. Many epidemiological studies address the relationship between mental disorders and global disease burdens, leading international agencies to insist on the design and implementation of social and public policy interventions in all countries. Despite global conviction and consensus on the relevance of mental health, there is not a single position that provides a consistent definition to guide all actions. Mental health is also mediated by the historical moment in which it is studied, and it also coincides with the biomedical approach that recognises mental health from its biological component, which is the brain, making it one more aspect of the physical dimension of health.

36 points out that mental health is determined by the individual’s characteristics, social, cultural, economic, political and environmental factors. From this new perspective, multi-sectoral and multi-level policies, which articulate the different sectors under the leadership of health, but based on promotion and prevention are required.

The category of university mental health includes research related to aspects involved in the psychological health and illness of university stakeholders. Currently, this dimension has few studies (Table 1), but there is a strong concern about issues affecting teachers in the organisational environment. Both in Spain and in Latin America, the characteristics of university environments as work organisations are similar to other environments, where the emergence of aspects such as stress, mobbing, burnout, and above all psychosocial and psycho-occupational factors currently stand out 36-38. In the case of Spain, the association of the specific contractual situations that have resulted from the economic crisis of recent years as a psychosocial factor of great magnitude for the teachers’ mental health is striking. This generates warnings mainly for Latin American universities, since the current economic situation has effects on the due financing of institutions and this in turn impacts on contractual conditions, weakening them and turning them into a threat to the health and well-being of teachers, employees, administrative staff and workers.

With regard to students, they highlight issues such as the consumption of psychoactive substances, tobacco, and alcohol, among others 39-41, mainly in Latin America, where school and university environments are besieged by micro-trafficking, alcohol and many other substances that are highly harmful to mental health. Due to the life cycle of university students 42, they are susceptible to depression and inadequate management of academic pressures exacerbated during assessment periods, and even to high rates of suicide 43 and early dropout, for which indicators and intervention technologies are already being developed. But this is an area that needs to be given greater attention from both a research and intervention perspective.

University social health

Nowadays, the relationship between social aspects and health is one of the essential issues of Public Health, and the SDOH constitute the framework to expose social inequalities in the living conditions of populations and from there to implement interventions at all levels. According to 44 this is actually not new, given that since the end of the 18th century when Public Health was established as a discipline, there has been interest in the influence of social conditions on the health and well-being of communities. Based on these considerations, social and public policies for the intervention of SDOH have been construed, seeking to leave behind the biomedical approach to health.

44 states that, for the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, the state interventions recommended to reduce health inequities require the articulation of all key sectors of society, aiming to improve living conditions and seeking a more equitable distribution of power, money and, in general, all resources.

Considering university campuses as microsocieties that are built according to the compositions and characteristics of the context in which they are located, social dynamics and phenomena impact university life, affecting the integral health of stakeholders.

The selected studies (Table 1) show how SDOHs are also an influential part of university scenarios, equality, equity 45, violence of all kinds, including gender-based violence 46,47, multiple sexual identities, multidiverse racial or ethnic discrimination, both work and sexual harassment and conflict resolution through violent acts. All these aspects have an impact on coexistence 48 and even affect the other dimensions of health, both in students and in all those who constitute university communities, hence the urgent challenge of studying, assessing and generating real responses from institutional policies and actions to favour the work and study environments under their jurisdiction in order to build environments for peace and coexistence where conflicts are dealt with peacefully, and rights and differences are respected.

University environmental health

In the framework of the SDOHs, environment is considered one of the most relevant, not only because the environmental conditions in which people live can generate harmful impacts for human beings, but also because the relationship is reciprocal, as the indiscriminate actions of individuals and communities on ecological environments also produce degradation, which is increased by the development models that rule the globalised world. The consequences of environmental degradation exacerbate ill health, impeding quality of life and overall sustainable development.

Taking into account the relevance of the environment as part of the SDOHs, universities, their different campuses and communities are involved in training, education, management, development of innovative and effective practices for the management of their resources: water, energy, air, fauna and flora, which model the campuses as responsible spaces for ecological sustainability, giving answers to face the harmful effects of climate change to all the surrounding environments. In this dimension the current acquis is still weak. The studies referenced in Table 1 indicate how the environmental dimension in universities should be given greater prominence in policies and interventions, as well as in research. Environmental management for global sustainability requires the commitment of all university stakeholders, as each person contributes to the deterioration or conservation of resources indispensable for life 49. In the first place, this component must be reinforced in the training activities that are part of the institutional mission, and the stakeholders are called upon to meet this challenge in common agreement and action. It is also necessary to analyse how the specific physical work environment, be it hygiene or safety, is a generator of problems to the physical and mental health of those exposed and requires effective interventions at each of the critical points, preserving integrity above all other considerations 34.

The construction of sustainable campuses is a great opportunity for universities to lead the changes that neither governments nor multilateral organisations, much less the private sector of the economy, have been able to achieve so far 50, due to the capacity of university institutions to influence their environments through the actions of their graduates.

University spiritual health

Spirituality can be understood as an individual perspective that translates into behaviours or practices that help to construct meaning from our being in relation to other beings and a universal spirit. Among the practices associated with spirituality are for example prayer, reading, meditation, contemplation, relaxation, harmonisation, extrasensory communication with oneself, with other beings or with a God, in general everything that symbolises a spiritual relationship. Although magical, supreme, divine or sacred powers have been granted to various beings, elements or human creations since ancient times, it was only at the beginning of the 20th century that a discipline such as psychology became interested in the relationships established between this dimension and human health, which led to the creation of the current known as the psychology of religion. The exponents of this current recognised the existence of a God, assuming religious practices as an object of knowledge.

For 51 spirituality as a construct that goes beyond the limits of religion and morality has gained much importance, particularly in the West, where research is being carried out to make use of it in the fields of therapeutic intervention and health in general. There is evidence in the literature of several studies that associate spirituality with different aspects of both physical and mental health. Recent studies in Mexico have identified spirituality, among other aspects, as an essential component in coping positively with events associated with pathological alcohol consumption 52,53. The contributions of spirituality to healthy lifestyles and practices in all dimensions of health are also beginning to be recognised.

The spiritual dimension, regardless of whether we are talking about universities with a denominational or secular focus, has been little addressed in studies and in interventions from the policies or programmes that are designed and offered for all university stakeholders, it is undeniable and mainly in Latin America that spirituality and/or religiosity is present in everyday environments, even in some universities there are chapels, churches or spaces for prayer depending on the predominant religious beliefs of the context. It is also evident that stakeholders bring their rituals, prayers, or spiritual expressions to campuses, whether through student, faculty or staff groups formed by their own initiatives, without institutional support or willingness in most cases.

In this dimension, only one study was referenced, that of 54, which describes and determines the relationship between psychological well-being, spirituality at work and perception of health in civil servants at the National University of Costa Rica. The study says that the subjective aspects of workers’ wellbeing should be considered in order to determine the areas to intervene in the promotion of university health, which opens the door for institutions to consider spirituality as a fundamental part of their interventions.

Although it is complex to define the concept of health today, as we have already seen, it is evident how important it is for the global and integral advancement of all societies, regardless of their development models, ideological, political, religious, cultural and other conceptions. Analysing the dimensions that interact within health is a necessary task if we want to improve the impact of interventions at all levels, since, as shown, going beyond the biomedical conception where what matters is the physical and now the mental component, helps us to explore articulated and integral paths, hence the social, environmental and spiritual dimensions from a holistic perspective, represent a challenge for actions throughout the cycle of health, especially in the stage of absence of problems associated with health. Incorporating the holistic perspective and deploying a salutogenic vision in all actions will have beneficial effects for people and their environments. On the other hand, university interventions must integrate all stakeholders (teachers, students, administrative staff, graduates and, where appropriate, retirees or pensioners); unidimensional actions aimed at a single stratum do not make it possible to build a truly healthy environment.

Conclusions

The studies selected in this review show us the relevance that the bio-medical vision of health still has in universities, given that there is a tendency to focus on physical aspects, with some importance given to mental aspects, and almost ignoring the social, environmental and spiritual ones.

The review also revealed a tendency to carry out studies and interventions with the student population, leaving teachers and employees in the background and ignoring other populations such as graduates, pensioners or communities neighbouring the campuses.

As universities are organisations with great capacity for learning and knowledge generation, they could generate innovations in terms of their approach to their interventions with all their stakeholders, even incorporating the communities surrounding their campuses in a more decisive manner. The stakeholder matrix (Figure 2) is an input to guide, monitor and evaluate interventions in healthy universities and its use is therefore recommended throughout the intervention cycle in order to create environments that are truly supportive of holistic health. All organisations have a great responsibility to build healthy environments. Universities are therefore responsible for creating the conditions for their campuses and environments to be conducive to the integral health of people in all its dimensions, guaranteeing the participation of their stakeholders and generating new relevant knowledge.