Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Colombiana de Reumatología

Print version ISSN 0121-8123

Rev.Colomb.Reumatol. vol.26 no.2 Bogotá Jan./June 2019 Epub May 20, 2020

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcreu.2019.01.004

Original Investigation

Cross-cultural adaptation of the Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD) in a Colombian population☆

a Sociomedical Sciences Program, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Ciudad de México, Mexico

b Departamento de Reumatología, Hospital General de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Grupo de Investigación Espondiloartropatías, Hospital Militar Central, Universidad de La Sabana, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

d Medicina Interna Reumatología, Universidad del Norte Barranquilla, Barranquilla, Colombia

e Asociación Colombiana de Reumatología, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

Introduction:

The validation of questionnaires is fundamental in the measurement process of any research study. The Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Dis eases (COPCORD) questionnaire is useful as a screening tool for the detection of rheumatic diseases.

Objective:

To adapt and validate the methodology and the COPCORD questionnaire in the Colombian population.

Materials and methods:

A validation study of the COPCORD methodology was carried out that included: (1) transcultural adaptation of the COPCORD questionnaire of Mexican Spanish, and (2) validation of the questionnaires: COPCORD, socioeconomic level questionnaire, use of health services and a quality of life questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L), following international guidelines.

Results:

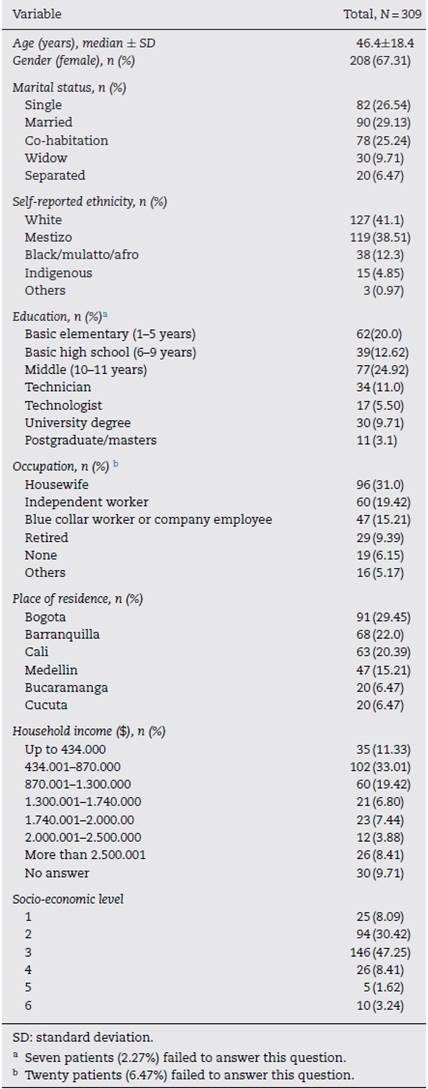

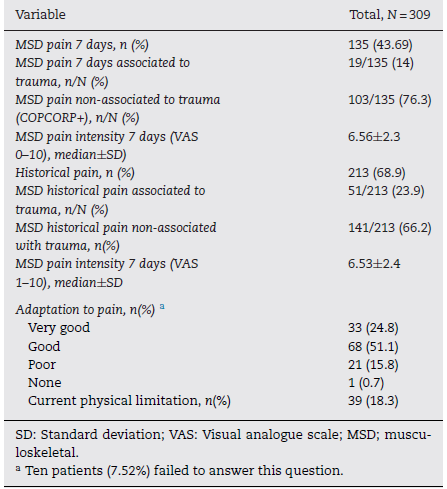

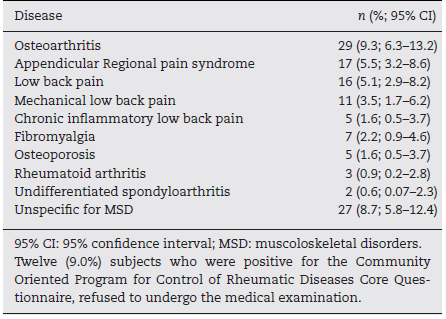

A total of 329 subjects of 6 cities in Colombia participated in the process, with 10 in the first phase and 309 in the second. Approximately two-thirds (67.3%) were women. The mean age was 46.4±18.4 years, with an educational level between basic and medium (77%). Participants resided in Bogota (29.4%), Barranquilla (22%), Cali (20.3%), Medellin (15.2%), Bucaramanga (6.4%), and Cucuta (6.4%). Musculoskeletal pain in the previous 7 days was reported by 43.6%, and historical pain was reported by 68.9%. A rheumatological diagnosis was established in 127 (41.1%) cases: osteoarthrosis (9.3%), regional pain syndromes (5.5%), low back pain (5.1%), and rheumatoid arthritis (0.9%). The internal validity was 0.70. When comparing the COPCORD questionnaire with the diagnosis made by the rheumatologist, it had a sensitivity of 70.8%, specificity 35%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.09 m and area under the curve of 0.53.

Conclusions:

The COPCORD questionnaire is valid as a screening test to detect musculoskeletal complaints and rheumatic diseases in the Colombian population.

Keywords: Cross-cultural validation; Musculoskeletal pain; Rheumatic diseases Colombia

Introducción:

La validación de cuestionarios es fundamental en el proceso de medición de cualquier estudio de investigación. El cuestionario Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD) es útil como tamizaje para la detección de enfermedades reumáticas.

Materiales y métodos:

Se realizó un estudio de validación de metodología COPCORD que incluyó: 1) adecuación transcultural del cuestionario COPCORD del español mexicano, y 2) validación de los cuestionarios: COPCORD, cuestionario de nivel socioeconómico, uso de servicios de salud y un instrumento de calidad de vida (EQ-5D-3L), siguiendo las guías internacionales.

Resultados:

Participaron 329 sujetos de 6 ciudades de Colombia, 10 en la primera fase del estudio y 309 en la segunda; un 67,3% fueron mujeres, con una edad promedio de 46,4 años, con una escolaridad entre básica y media (77%). Los participantes residían en Bogotá (29,4%), Barranquilla (22%), Cali (20,3%), Medellín (15,2%), Bucaramanga (6,4%) y Cúcuta (6,4%). Repor taron dolor musculoesquelético en los últimos 7 días el 43,6% y dolor histórico el 68,9%. En 127 (41,1%) se estableció un diagnóstico reumatológico: osteoartrosis (9,3%), síndrome de dolor regional (5,5%), lumbalgia (5,1%) y artritis reumatoide (0,9%). La validez interna fue de 0,70. Al comparar el cuestionario COPCORD con la revisión por el reumatólogo, tuvo una sensibilidad del 70,8%, una especificidad del 35%, una razón de verosimilitud positiva de 1,09 y un área bajo la curva de 0,53.

Conclusiones:

El cuestionario COPCORD es válido como prueba de tamizaje de detección de malestares musculoesqueléticos y enfermedades reumáticas en población colombiana.

Palabras clave: Validación transcultural; Dolor musculoesquelético; Enfermedad reumática; Colombia

Introduction

The impact of rheumatic diseases has been well documented in high income countries and to a lesser degree in the devel oping countries.1 These diseases represent the number one cause of permanent disability in industrialized countries, with a significant socio-economic impact, and worsening of the quality of life of the individuals affected.2 Early detection and diagnosis, healthcare intervention, and rapid and effective therapy are all key to reduce or reverse the physical and social disability resulting from these conditions.3

The Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD) methodology has proven to be an effective tool to estimate the prevalence of mus culoskeletal disorders (MSD) and rheumatic disease in the general population.4 The objective of this program is to obtain reliable epidemiological information through low cost studies conducted in the community.2,4 The COPCORD methodology includes three stages: stage I corresponds to the epidemiolog ical phase; stage II corresponds to treatment and education strategies; and stage III, corresponds to the identification of environmental and genetic risk factors of rheumatic diseases. The Core COPCORD Questionnaire (CCQ) is administered in Stage I, with a view to do a screening for the detection of rheumatic diseases.4

The COPCORD methodology has been used in several countries over the past 3 decades.5-11 Using a standardized methodology enables a comparison of the studies conducted in different populations, and the identification of factors asso ciated with such variability.

As part of Stage I of the COPCORD methodology, Pfleger sug gests that the CCQ screening questionnaire be cross-culturally validated and adapted to the local conditions and to the lan guage of the target population. The validation of the CCQ questionnaire in its original English version translated into other languages and cultures is seldom reported in detail in the COPCORD studies.2,12

In Latin America, COPCORD studies have been conducted in Cuba,13 Venezuela,10 Mexico,11,14,15 Brazil,16 and Ecuador.17 Studies have also been conducted in indigenous populations for whom the COPCORD questionnaire in Spanish had to be translated into 7 indigenous dialects: warao, karma, and chaima (Venezuela); mixteco, maya-yucateco and rarâmuri (México) and qom (Argentina).18

Validation processes of the methodology and the COPCORD questionnaire in different Latin American countries have been reported.17-20 The Mexican version 2 of the COPCORD19 was used as a reference for the Colombian population, because of its availability and complete validation process, and it has been the foundation for most of the studies conducted in the region.9 Since the personal answers to the question naire vary from one culture to another, its use is conditioned by the local context in which the questionnaire is admin istered. Therefore, there is a need to do an adaptation and cross-cultural validation comprising two steps: the lan guage adaptation with an assessment of the conceptual, semantic, and operative aspects, and the validation of the instrument.9

The objective of this study is to adapt and do a cross-cultural validation of the COPCORD methodology and the CCQ questionnaire to identify any MSD and rheumatic diseases among the Colombian population. Furthermore, the intent is to use the performance of the CCQ questionnaire as a screening test for rheumatic diseases.

Materials and methods

Design

Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the methodology and of the screening questionnaire (COPCORD) Mexican ver sion 219 to identify rheumatic disorders and diseases.

Cross-cultural adaptation

This was done pursuant to the proposal by Beaton et al.,21 that defined cross-cultural adaptation as a process that observes both parts of the cultural and language adaptation in the pro cess of developing a questionnaire for use in other contexts. They argue that this process shall be adapted in accor dance with 4 different aspects: the target population (natives, established immigrants, new immigrants), the culture, the language, and the country.

The process of adaptation involves 7 steps: (1) translation; synthesis of translations; (3) back translation; (4) expert committee; (5) pre-final version test; (6) document review for developers; and (7) cross-cultural adaptation that includes an evaluation of the conceptual, semantic equivalence by item and operational22; Step 8 involves the process of validation of the adaptation, in order to assess the equivalence in mea surements (psychometric and clinimetric properties of the questionnaire).23 Since a Mexican Spanish version that met all the adaptation requirements suggested (i.e., steps 1-6) was available, a cross-cultural adaptation was put together, includ ing steps 7 and 8 only.

Population

The participants were adults aged 18 and over, who had lived for more than 6 consecutive months in the following cities: Cali, Cucuta, Medellin, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, and Bogotá.

Convenience sampling was used, and the sample size was estimated pursuant to the recommendations by Terwee et al. for this type of design.24

COPCORD methodology

The following steps were completed: (1) the surveyors and the coordination staff were trained and homogenized; (2) the study population was invited to participate and the informed consent of the participants from each community was signed; 2 pilot tests were conducted, one for adaptation of the questionnaires in 10 subjects and the second one for validation and evolution of the field strategy in 300 subjects: (4) individuals over 18 years old who had lived in the same address for at least 12 months at the time of the interview were selected; (5) the CCQ-COPCORD, functional capacity (Health Assess ment Questionnaire Disability Index), biomechanical stress, and socio-economic status questionnaires were home admin istered (if the person was not at home, the interviewer paid at least 3 visits, at different times and days of the week, including holidays, to obtain the information); (6) the surveys were crossed-reviewed among the surveyors on the same day they were administered and were subsequently checked by the coordinators; (7) The COPCORD positive patients underwent a clinical checkup by a resident physician of a postgraduate pro gram in rheumatology (the definition of positive was applied to those cases in which MSD pain of more than 1 was reported, in a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10, during the past 7 days, or pain at any point in their life, including trauma-associated pain); 8) any subjects with suspicion of rheumatic disease were assessed in the community by a certified rheumatologist to confirm the diagnosis and subsequent follow-up. The diagnosis was done using the International Classification of Diseases, and the criteria of the American College of Rheuma tology for rheumatic diseases. The time elapsed between the interview and the medical evaluation was maximum 7 days. Radiographs and laboratory tests were ordered as needed.

Measurements

Screening questionnaire for rheumatic diseases CCQ-COPCORD

In this study the Mexican version 2 was used for the cross-cultural adaptation.19

The CCQ-COPCORD questionnaire validated in Mexico, version 2, comprises the following sections: explanation, demographic information, self-reported comorbidities, pain in the past 7 days, pain at any point in time in their life, location on the dummy, pain intensity measured on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10, duration, pain behavior patterns, type of care sought (biomedical, surgical, traditional), func tional limitation due to pain, pain adaptation and functional capacity measured by the Bruce and Fries's Health Assessment Questionnaire.25

This questionnaire identifies individuals with rheumatic symptoms through an interview with trained surveyors. The average time for administering the survey is 8 min. It includes questions associated with symptoms (pain and stiffness, disability, treatment, and adaptation to the problem). This instrument includes a section on behavior to search help and a list of non-conventional medications (Annex 1).

Functional capacity and biomechanical stress

The functional capacity was measured using the Health Assessment Questionnaire. The biomechanical stress was considered an important variable due to its association with MSDs and rheumatic diseases; such questionnaire was devel oped to enquire on the biomechanical load in activities of daily life.

Socio-economic status

This questionnaire, structured with a view to typify the pop ulation participating in an epidemiological study, comprises the following items: age, gender, self-qualified ethnicity, mari tal status, occupation, education, healthcare service used, and other items (Annex 1).

The process of cross-cultural adaptation was conducted as follows:

Phase 1 - Review of the process and questionnaires by a multidisciplinary committee (rheumatologists, epidemiologists, immunologists, internists, experts in methodology). Discuss ions were held with the committee in full until a preliminary version of the questionnaire in Colombian Spanish was com pleted, checking for semantics, language, conceptual and cultural equivalence.

Phase 2 - Test of version 1. Anew pre-pilot test was conducted with the version agreed in phase 1. Colombian individuals over 18 years old, with or without osteomuscular symptoms were included. Consecutive convenience sampling was used to obtain the desired sample size, from 7 randomly selected households in the Kennedy and Usaquen neighborhoods. An assessment was made to make sure that the language was clear, the drafting was appropriate, and that the questions were comprehensible, in addition to the rating scale for the questions in the questionnaire. A sample of 10 participants was selected, 6 healthy and 4 with osteomuscular symptoms, whose mother tongue was Colombian Spanish. An in-depth interview was administered assessing comprehension, under standing item by item, and any items exhibiting difficulties were revised.

Phase 3 - Review of version 2. Any spelling, grammar, and typing errors were revised. The changes recommended by the participants in phase 2 were included.

Phase 4 - Submission to the committee of experts and partici pating researchers. Discussion groups were held at the experts' committee; notes were taken during the meetings to make all the changes and adopt the recommendations of the commit tee to version 2, which was presented and discussed with the whole group of researchers participating in the study, in order to get a final version (version 3) approved for validation.

Phase 5 - Validation of Final Version (version 3). Adminis tration of questionnaires to individuals in each city, use of convenience sampling; the sample size was based on Terwee et al.24 The final adapted version 3 was used. The positive subjects (pain, stiffness and swelling in any part of the body during the last 7 days or any time in their life) were assessed by the group of family doctors (internists) and rheumatologists, to establish a diagnosis in accordance with the international criteria for rheumatic diseases. The purpose of this phase was to assess all of the psychometric charac teristics (construct validity, internal validity, performance as a screening test, and predictive validity) of CCQ-COPCORD questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

The approval of the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Universidad de La Sabana was obtained. Upon a detailed explanation about the study, each participant accepted to be part of the research project and signed the informed consent.

Statistical analysis

An analysis of the variables was completed, reporting cen tral tendency and dispersion measurements in continuous variables, and absolute and relative frequencies in ordinal, nominal, or categorical variables.

Cronbach's alpha was measured, considering a dimension criterion; values below 0.70 are interpreted as multidimen sional and above 0.70 are interpreted as unidimensional.26 Correlation matrixes were developed using the Spearman test for the CCQ dimensions.

Construct validity: The MSDs and pain course were con trasted against the clinical assessment by the rheumatologist.

Performance of the screening test: An analysis was carried out comparing the pain course (over the past 7 days, and histor ical pain) against the clinical assessment and final diagnosis established by the rheumatologist, through an estimate of the sensitivity, specificity, the plausibility, and the areas under the ROC curve and 95% confidence intervals.27

The analysis was conducted with the Stata v 11.0 statistical software for MAC.

Results

Phase 1 - Review of the process and questionnaires by a multidisciplinary committee. A section on demographic data was included, intended to typify the individual in terms of social conditions, family group, housing, ethnicity, and healthcare-social security status (Annex 1. P14-P18, P20, P21, P24). Under the comorbidities section, the item that characterizes cigarette use became a continuous variable because the actual data was required for subsequent analysis.

Phases 2 and 3-10 individuals participated, 6 females and 4 males. The mean age was 54.7±20.3 years. The group proposed the following changes in the socio-economic questionnaire: classify the questions intended to identify the healthcare com pany to which each individual was affiliated, as well as the average monthly income, because of the potential reserva tions about such information, and the discontent of some people when analyzing the instrument. The Health Assess ment Questionnaire, with regards to the items associated with the use of mobility aids, specifying the type of aid that could be used by individuals, with a view to collect accurate infor mation. In terms of items P11 and P11a, that address the identification of the caregiver for everyday activities, in con trast to the original document, the decision was adopted to include one item specifying the daily activities in which the caregiver is involved, with a view to indirectly know the level of disability of the individual.

Phase 4 - The multidisciplinar/y committee, taking all the recommendations from the previous phases into account, agreed to organize the instrument into 4 sections: (1) Sociode mographic characteristics; (2) Diagnostic assessment and severity of the osteomuscular disease; (3) economic status; and (4) insurance of the individual. Therefore, the items that characterized the socioeconomic status were modified to assess the level of income and the drafting of the item on limitation to labor access because the individual's physical condition changed, and was included in the section on diag nostic assessment and severity of the osteomuscular disease (Annex 1).

Phase 5 - 309 subjects were surveyed (29.45% from Bogotá, 20.30% from Cali, 22.0% from Barranquilla, 15.21% from Medellin, and 6.47% from Bucaramanga, and Cucuta); 67.31% were females. The rest of the sociodemographic characteris tics are described in Table 1.

Table 2 illustrates the results of the pain domain in the CCQ questionnaire; 135 expressed having non-specific MSDs pain in the last 7 days and 213 (68.9%) expressed pain at some point in their lives or historical pain.

In 127 (41%) (12 refused medical check-up) a rheumatologic diagnosis was established in the community. The most com mon were osteoarthritis, regional pain syndrome, and lower back pain (Table 3).

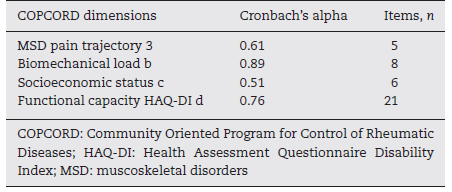

Validity analysis

When conducting an internal validity analysis based on the measurements of the COPCORD questionnaire, Cronbach's Alpha was found to range from 0.89 for biomechanical load, to 0.51 for socioeconomic status (Table 4).

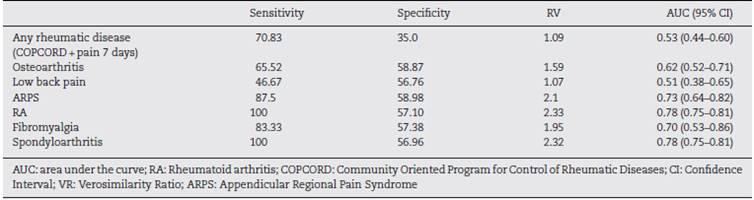

Performance of the COPCORD screening test analysis

When analyzing the performance of the COPCORD question naire using the 2 questions enquiring about pain in the past 7 days and historical pain (pain in the last 7 days as proxy for chronic pain) versus the diagnosis established by the rheumatologist, the resulting sensitivity was 70.8%, the speci ficity was 35%, a positive verosimilarity ratio of 1.0, and an area under the curve of 0.53. The results per rheumatic dis ease diagnosed varied from a sensitivity of 46.6 to 100%, and a specificity of 35 to 58.8% (Table 5).

Discussion

The COPCORD methodology and the modified CCQ-COPCORD questionnaire performed well as a screening test for muscoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases in the Colombian cities evaluated. 5 cross-cultural validations have been reported in developing countries using different validation methods.

The results obtained from the first cross-cultural validation of the methodology and the COPCORD instrument in Latin American mestizo populations from Mexico, Brazil and Chile, report a generic sensitivity and specificity of the instrument of only 84% and 80.2%, respectively.1

In Kuwait, the sensitivity and specificity reported are 94.3% and 98.8%, respectively,28 which is higher than the results from our study. This may be due to differences in the definition of positive COPCORD. The first 2 studies considered positive the non-trauma associated musculoskeletal pain over the past 7 days and a pain intensity of more than 4 points in the pain visual analogue scale. In this study, a positive COPCORD was not limited to the association to trauma, or the pain intensity. When comparing our results against those of other validations conducted in Latin America, the sensitivity to detect any rheumatic disease is higher (70.83%) than the one reported in Ecuador (62.0%) and Mexico (51.7%),19 but similar to those of the Latin American indigenous commu nities (73.8%). In terms of specificity, it is lower than the one reported in other studies. 18

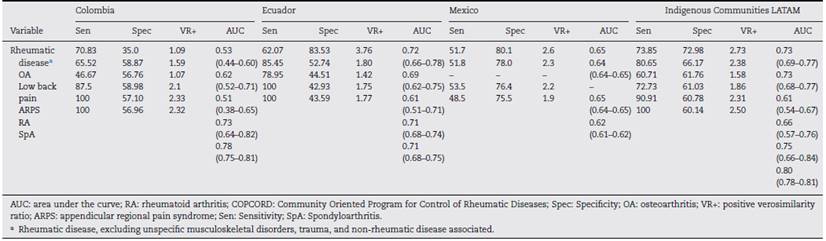

The performance of the CCQ-COPCORD questionnaire, as a screening tool for each of the most common rheumatic diseases (osteoarthritis, low back pain, regional syndromes spondyloarthritis), ranges from fair to very good in terms of sensitivity and specificity. The performance was superior to detect rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, regional syn dromes and fibromyalgia, which is consistent with the reports of the study conducted in Ecuador, with Latin American indigenous peoples (Table 6).

Table 6 Comparison of the performance of the COPCORD questionnaire as a screening test for the detection of rheumatic diseases in various studies in Latin America.

The results of the measurements and internal validity with Cronbach's alpha, were interpreted pursuant to Sijtsma's proposal, 26 classifying the very low scores as separate multi dimensional sets, and the very high scores as unidimensional sets of the questionnaire; such is the case of the socioeco nomic status (0.51) and the biomechanical load (0.98); the internal validity was moderate for pain trajectory (0.61) and functional capacity (0.76). The total validity was 0.70. A pos sible explanation for the low results is that the data for the item socioeconomic status are multidimensional. The general validity of our study is lower than the validity of the Kuwaiti population with 0.97.28 Only the studies from Ecuador9 and in indigenous peoples, report the internal validity based on dimensions; although these vary, there is consistency in terms of pain trajectory, which in our study was reported at 0.66; this number is below the number reported for indigenous peoples (0.77) 18 but higher than the figures reported in the Ecuadorian study (0.17). 9

It should be highlighted that this version included biomechanical load, a measurement never reported before, which resulted in a very strong internal validity. Therefore, the recommendation is to include the biomechanical load measurement in future versions of the COPCORD question naire.

Whilst the objective of this study was not to estimate the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic dis eases, it can be seen that the frequency of MSD and rheumatic diseases is similar to what has been reported in other vali dation studies. 18,19,21

Limitations

Sensitivity to change was not assessed as part of the vali dation, since the COPCORD questionnaire is for screening purposes and not to make comparisons through any interven tion.

No test-retest reliability was conducted because of the lim itation of a second assessment in less than 7 days, the ability to access the populations, and the limitation of human and economic resources.

Conclusions

Questionnaire CCQ-COPCORD is valid for use in the Colombian population as a screening test for musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases. Biomechanical load was a measure added to the Colombian version, since it its an important measurement as an associated factor to the prevalence of rheumatic diseases, and in particular regional pain syn dromes. The performance of the questionnaire as a screening test is good.

Acknowledgements

- Universidad de La Sabana.

- Centro Nacional de Consultoría.

- EuroQol Research Foundation.

- Grupo de Estudio Epidemiológico de las enfermedades.

- Músculo-Articulares (GEEMA)-Colegio Mexicano de Reumatología.

REFERENCES

1. WHO Scientific Group on the Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions at the start of the new millennium. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;919:i-x, 1-218, back cover. [ Links ]

2. Pfleger B. Burden and control of musculoskeletal conditions in developing countries: A joint WHO/ILAR/BJD meeting report. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1217 [ Links ]

3. Guillemin F Carruthers E, Li LC. Determinants of MSK health and disability-social determinants of inequities in MSK health. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28:411-33. [ Links ]

4. Chopra A, Abdel-Nasser A. Epidemiology of rheumatic musculoskeletal disorders in the developing world. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:583-604. [ Links ]

5. Muirden KD. Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases: Studies of rheumatic diseases in the developing world. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:153-6. [ Links ]

6. Chopra A. The WHO ILAR COPCORD Latin America: Consistent with the world and setting a new perspective. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:167-9. [ Links ]

7. Peláez-Ballestas I, Pons-Estel BA, Burgos-Vargas R. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases in indigenous populations in Latin-Americans. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35 Suppl 1:1-3. [ Links ]

8. Cardiel MH, Burgos-Vargas R. Towards elucidation of the epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases in Mexico. COPCORD studies in the community. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;86:1-2. [ Links ]

9. Guevara-Pacheco S, Feican-Alvarado A, Sanin LH, Vintimilla-Ugalde J, Vintimilla-Moscoso F, Delgado-Pauta J, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases in Cuenca, Ecuador: A WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1195-204. [ Links ]

10. Granados Y,Cedeno L, Rosillo C, Berbin S, Azocar M, Molina ME, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases in an urban community in Monagas State, Venezuela: A COPCORD study. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:871-7. [ Links ]

11. Del Río Nájera D, González-Chávez SA, Quinonez-Flores CM, Peláez-Ballestas I, Hernández-Nájera N, Pacheco-Tena CF. Rheumatic diseases in Chihuahua, Mexico: A COPCORD Survey. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:188-93. [ Links ]

12. Chopra A, Saluja M, Patil J, Tandale HS. Pain and disability, perceptions and beliefs of a rural Indian population: A WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. WHO-International League of Associations for Rheumatology. Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:614-21. 13 Reyes-Llerena GA, Guibert-Toledano M, Penedo-Coello A, Pérez-Rodríguez A, Báez-Dueñas RM, Charnicharo-Vidal R, et al. Community-based study to estimate prevalence and burden of illness of rheumatic disease in Cuba: A COPCORD study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:51-5. [ Links ]

13 Reyes-Llerena GA, Guibert-Toledano M, Penedo-Coello A, Pérez-Rodríguez A, Báez-Dueñas RM, Charnicharo-Vidal R, et al. Community-based study to estimate prevalence and burden of illness of rheumatic disease in Cuba: A COPCORD study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:51-5. [ Links ]

14. Cardiel MH, Rojas-Serrano J. Community based study to estimate prevalence, burden of illness and help seeking behavior in rheumatic diseases in Mexico City. A COPCORD study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:617-24. [ Links ]

15. Peláez-Ballestas I, Sanin LH, Moreno-Montoya J, Álvarez-Nemegyei J, Burgos-Vargas R, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases in Mexico. A study of 5 regions based on the COPCORD methodology. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;86:3-8. [ Links ]

16. Senna ER, de Barros AL, Silva EO, Costa IF, Pereira LV, Ciconelli RM, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Brazil: A study using the COPCORD approach. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:594-7. [ Links ]

17. Bennett K, Cardiel M, Ferraz M, Riedemann P, Goldsmith C, Tugwell P. Community screening for rheumatic disorder: Cross cultural adaptation and screening characteristics of the COPCORD Core Questionnaire in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. The PANLAR-COPCORD Working Group. Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of Rheumatic Disease. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:160-8. [ Links ]

18. Pelaez-Ballestas I, Granados Y Silvestre A, Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Valls E, Quintana R, et al. Culture-sensitive adaptation and validation of the community-oriented program for the control of rheumatic diseases methodology for rheumatic disease in Latin American indigenous populations. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:1299-309. [ Links ]

19. Goycochea-Robles MV, Sanin LH, Moreno-Montoya J, Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Burgos-Vargas R, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. Validity of the COPCORD core questionnaire as a classification tool for rheumatic diseases. J Rheumato Suppl. 2011;86: 31-5. [ Links ]

20. Moreno-Montoya J, Avarez-Nemegyei J, Trejo-Valdivia B, Pelaez-Ballestas I. Assessment of the dimensions, construct validity, and utility for rheumatoid arthritis screening of the COPCORD instrument. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:631-6. [ Links ]

21. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186-91. [ Links ]

22. Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, Aaronson N. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. 2008;11:509-21. [ Links ]

23. Reichenheim ME, Moraes CL. [Operationalizing the cross-cultural adaptation of epidemiological measurement instruments] Portuguese. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41:665-73. [ Links ]

24. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42. [ Links ]

25. Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: Dimensions and Practical Applications. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20. [ Links ]

26. Sijtsma K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika. 2009;74:107-20. [ Links ]

27. Bewick V, Cheek L, Bal J. Statistics review 13: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004;8:508-12. [ Links ]

28. Al-Awadhi A, Olusi S, Moussa M, Al-Zaid N, Shehab D, Al-Herz A, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the WHO-ILAR COPCORD Core Questionnaire for community screening of rheumatic diseases in Kuwaitis. World Health Organization. International League Against Rheumatism. Community Oriented Program for the Contro of Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1754-9. [ Links ]

☆Please cite this article as: Peláez Ballestas I, Santos AM, Angarita I, Rueda JC, Ballesteros JG, Giraldo R, et al. Adecuación y vali dación transcultural del cuestionario COPCORD: Programa Orientado a la Comunidad para el Control de las Enfermedades Reumáticas en Colombia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2019;26:88-96.

Funding The authors received non-conditioned economic support from the Colombian Association of Rheumatology (Minutes No. 156 of 2015) that enabled the completion of this project.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.rcreue.2019.01.010.

Received: February 02, 2018; Accepted: January 21, 2019; other: April 02, 2019

text in

text in