Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the development of autoantibodies capable of causing damage to different organs, tissues and healthy cells1,2. Its nature is fluctuating since it oscillates between periods of remission and exacerbation3 and its cause is unknown, although a possible etiological relationship between genetic, hormonal and environmental factors has been determined4.

Worldwide, women represent between 80 and 90% of cases in adults. The races of Afro-American, Hispanic, Asian and Indigenous descent, and the ages between 15 and 45 years are the main risk factors for developing the disorder5. In Colombia, the disease behaves in a similar way, with a female: male ratio of 9:1, being Bogotá the city where the highest number of patients diagnosed with SLE reside6.

The significant impact of the disease on the quality of life of the people who suffer from it has been a phenomenon of interest, especially for the high affectation that SLE generates on the physical well-being of the individual7. The most frequently reported symptoms are fatigue and pain, which limit functioning in everyday life7,8. Likewise, cognitive alterations have an impact on the deterioration of work and school performance, which is conceived as troublesome8.

On the other hand, the fluctuation of the disease is usually associated with uncertainty, the subjects also report feelings of anxiety, hopelessness and low mood, which indicates that SLE has repercussions on the mental health and the emotional state of the patients, who, immersed in such multiplicity of conditions, frequently report the difficulty that coping with the disease represents7,8.

For women with SLE there is a high impact on mental health and social functioning. Cutaneous manifestations and hair loss appear to have a negative influence on personal identity and self-esteem8. Likewise, the oscillating characteristic of the symptomatology as a factor that interferes with the execution of roles associated with caring for others and the sexual life as a couple is highlighted8.

However, certain facilitating aspects have also been found in the lives of people with SLE, such as: positive attitudes, respect for those who are close to them, acceptance of the disease and being aware of the need for self-care7.

In fact, in young people, that is, those who are still under certain subordination to the adult condition9, the arrival of a chronic disease can be perceived as an impediment to the execution of the life project10. The diagnosis itself is unexpected10, which is why a certain complexity in the process of coping with the disease is presumed, especially during the first three years with the disease, as relevant periods are considered for the acceptance of the new condition of chronicity11,12.

In view of that was exposed in the preceding paragraphs, the present study was developed with the purpose of inquiring on the life experience of young women with a recent diagnosis of SLE, since so far the findings on the experience of the disease in this population are scarce.

Materials and methods

A study with qualitative approach of descriptive phenomenological type was conducted, following the theoretical approaches of Edmund Husserl, to take a look to the facts as people experience them. Descriptive phenomenology is aimed at understanding the experience lived as a whole, it does not look for causal relationships, so that the reality of the subjects is constructed from a descriptive analysis of the life experiences, for which the researchers abandon their previous conjectures13.

For this reason, prior to the analytical tasks, a phenomenological reduction process was carried out, understood as the intellectual process of deep reflection before the immersion in the new knowledge. In the same way, the correspondence between the data was continuously analyzed throughout the study, in compliance with the purpose of finding the meanings and proposing their structures for the description of the experience lived by the young woman with SLE14,15.

The study included young women between 18 and 26 years of age with a diagnosis of SLE for no more than three years, according to the criteria of the European League Against Rheumatism and the American College of Rheumatology) (EULAR and ACR) (16, of Colombian nationality and residents in the city of Bogota. The exclusion criteria were having any condition that would prevent them from participating in the study or being pregnant. The intentional snowball sampling technique was used, by means of contact through social networks using a graphic piece.

An approach meeting was held, in which, in addition to creating the first contact, the aspects related to the study and the informed consent procedure were explained to each participant, clarifying voluntary participation and other ethical considerations. Subsequently to this, in-depth interviews were done between July and October 2019 with the guiding question how has it been for you living with systemic lupus erythematosus? The interviews were recorded and transcribed, their average duration was 68.4 minutes and their content was verified by each researcher as a guarantee for the integrity of the stories. In addition, field notes were made that were contrasted with the audios and linked to the analysis of the results.

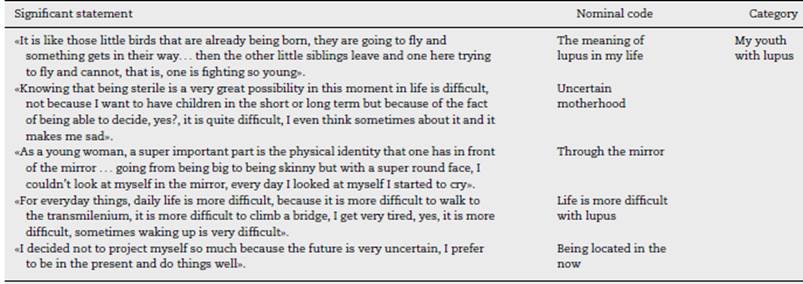

The data were analyzed using the Colaizzi's method17, from which the description of the life experience of a young woman with a recent diagnosis of SLE was constructed. Initially, each interview was divided line by line and significant statements were extracted. To these, it was assigned a code per participant (M1-M5), followed by the interview number (E1-E5) and the numbering of the sentence (from 1 to the amount found). From the significant statements, nominal codes were formulated, which were grouped into common senses and gave rise to the four categories that describe the phenomenon in detail (Table 1).

Theoretical saturation was achieved since new data on the verbalization of the experience of the participants were no evidenced. Once the results were generated, they were socialized with the 5 women interviewed, who reported to feel identified with the description of the experience.

This study is part of a research macroproject of the National University of Colombia (Universidad Nacional de Colombia) -based in Bogota and had the endorsement of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine issued in Act No. 008-108-19.

The criteria of methodological rigor for qualitative research proposed by Guba and Lincoln18, the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki, the Nuremberg Code and Resolution 8430 of 1993 issued by the Colombian Ministry of Health were met19. Likewise, confidentially regarding the identity and the information provided by the participants was guaranteed.

Results

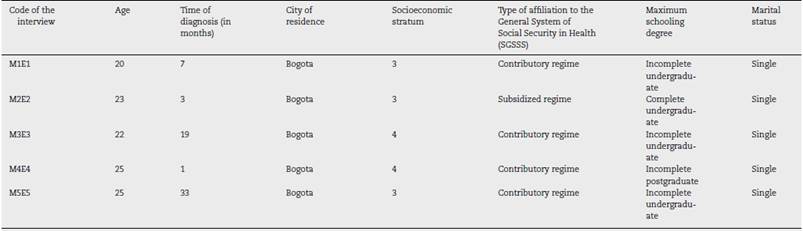

In-depth interviews were done to five women between the ages of 21 and 26 years, with an average of 12.6 months after having received the diagnosis of SLE, all residents in the city of Bogota and with marital status single, with different levels of schooling, socioeconomic conditions and healthcare affiliation regime (Table 2).

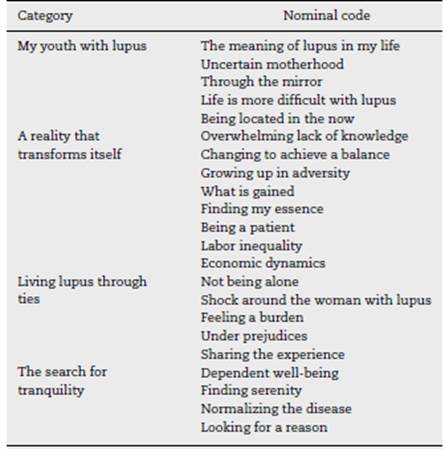

268 significant statements and 22 nominal codes were extracted from the stories, which were grouped into common senses and gave rise to the 4 categories that describe in detail the life experience of the young women with a recent diagnosis of SLE, as follows: «my youth with lupus», «a reality that transforms itself», «living lupus through ties» and «in search of tranquility» (Table 3).

Table 3 Description of the life experience of the woman with a recent diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Source: own elaboration.

The experience of the woman with a recent diagnosis of SLE diagnosis is described in detail below.

My youth with lupus

The young woman recognizes that the disease has come into her live for a reason, to allow her to glimpse what would not have been possible otherwise. She gives the meaning of challenge to her suffering, which requires an overcoming response and at the same time implies the flowering of her innate strength: «it basically represents for me a challenge that I must overcome emotionally and physically» (M4E1F11).

The diagnosis of lupus that comes unexpectedly into the life of a young woman takes on multiple representations. It is seen as a punishment, an opportunity, a teaching or an obstacle. In the youth, many processes are truncated by the new way of living, different from what is expected for the age. She feels she is aging early: «It is like those little birds that are already being born, they are going to fly and something gets in their way... then the other little siblings leave and one here trying to fly and cannot, that is, one is fighting so young» (M2E1F20).

In a stage plenty of fertility, one of the aspects that more restlessness generate in the young woman with lupus is the possibility of getting pregnant, motherhood is uncertain. However, even when there is no explicit desire, anxiety is related to the loss of autonomy to make a decision as important as having a child: «knowing that being sterile is a very great possibility in this moment in life is difficult, not because I want to have children in the short or long term but because of the fact of being able to decide, yes?, it is quite difficult, I even think sometimes about it and it makes me sad» (M3E1F33).

Self-image also takes a representative value in the young woman with lupus, her changes in physical appearance derived from both the disease and the treatment make her unrecognizable, and the woman is surprised to see someone completely different in front of the mirror. Even so, she recognizes the importance of adapting to her new appearance: «I washed my hands and when I turned to look at the mirror I felt frightened because I saw another person completely different from me in the mirror and when I was concentrated it was: -ah, It's not that it's me- now I'm like that and I have to get used to seeing myself like that, but the change was so much that it actually scared me» (M5E1F12).

The loss of physical identity generates emotional discomfort, her self-perception changes and she fears criticism from others. The woman does not want to leave her house, but when she does, she prefers to hide her face and her hands, which are the parts of her body that have changed the most. This same situation decreases her self-esteem and increases her insecurities: as a young woman, losing vanity and identity is hard, very hard» (M3E1F35).

The disease is conceived as a difficult process, the young woman manifests the complexity of a life with lupus: «for everyday things, daily life is more difficult, because it is more difficult to walk to the transmilenium, it is more difficult to climb a bridge, I get very tired, yes, it is more difficult, sometimes waking up is very difficult» (M5E1F1). On a physical level, symptoms are the main source of discomfort, pain and fatigue stand out: «it's a bit complex, before you didn't feel pain when you got up, like heaviness, like cracking your fingers . . . how is living it? It is complicated, but manageable» (M4E1F36).

On the other hand, there are the emotional ups and downs that derive from the entire process of the disease and especially from the impact after the diagnosis: (emotionally it has been difficult, it has been challenging (M2E1F27). The woman feels mentally weak to confront the situation, an enormous sadness invades her and she goes into shock: «I was not sick and from one moment to another, everyone's life changes, one does not know how to react . . . this is the shock that I mean» (M3E1F48).

For the young woman, having lupus also means a change in her way of visualizing the future, this implies enjoying day-today life in its maximum splendor without anticipating what will come tomorrow: «I decided not to project myself so much because the future is very uncertain, I prefer to be in the present and do things well» (M5E1F21).

The young woman with lupus lives the experience of a daily battle against something inherent to her, this attack is mediated by the symptoms and the physical, psychological, emotional and social repercussions of the disease: « What meaning . . . it is like being a warrior, that is, the girls who have lupus and the few boys, every day they wake up fighting against themselves literally because it is one against one» (M2E1F18).

The woman feels that she is in a full beginning of work productivity, academic achievement and social interaction, which are hampered by the new condition. However, the life cycle in which they find themselves allows them to face the situation and adapt to the new way of life: «it is as if you are aging young, so it is very funny, I go many times to the neurologist and to the rheumatologist and you only see old people, then it is practically an old man living in the body of a young woman. . . it is not easy to live with lupus at an early age when you feel that you have many things to do, you want to do things and the simple fact of suffering from this does not let you ... What is it like to live? It is to live complicated, that is, to have a complicated life» (M4E1F48).

A reality that transforms itself

The newly diagnosed young woman generally knows very little about lupus, and when discussing the matter with others she realizes that the disease is unknown: generally people do not know what lupus is, they have no idea, even explaining it is sometimes difficult... A disease that, in the end, is rare, yes, it is not very common» (M3E1F44). This awakens in her a spirit of inquiry, so she begins her search in the available sources in order to find the cause of what is taking place in her body and to have knowledge about what may happen in the future: «I took on the task of starting to read, to start researching about the disease, there is not much information actually, but the one that exists is often clear and concise, this allowed me to understand many things that were happening and that could happen» (M1E1F42). With the information obtained, some of the questions that overwhelm her are answered, however, doubts remain and a certain lack of knowledge persists.

The disease is fluctuating, it can appear at the door in an acute and even fatal way, or appear through a window in a hidden, almost asymptomatic way. This entails a path full of uncertainty in which several feelings appear, among which the fear of the possible activation of the disease stands out: «It is like living in fear, because you do not know, you do not know so much about this, you do not know if anything you do can affect you» (M1E1F38).

In the search for remission, the young woman reconstructs her lifestyle, she tries to be healthier, leaving behind harmful behaviors: « If that had not happened to me, I think I would continue smoking cigarettes, perhaps I would be more partying and I would not be doing so much exercise or taking care of my diet» (M2E1F7). There is a change of perspective derived from the process of the disease, this allows her to recognize the importance of her being and the integral care of herself: «it happens to me this and there I realize that I have to change many things in my life, that I have to improve, in a certain way I save more than the body, my mind » (M3E1F23).

Intense physical, psychological, emotional and social changes come after the diagnosis of a chronic disease, the young woman lives in a dynamic and challenging environment. There are days when pain and fatigue become distressing, the battle is with herself and it touches the psyche. There is a determination to face it, not to be defeated, strength sprouts not to let her go down, to face the disease and to show the world and herself that it is possible to live with it: «I know that I have a disease and sometimes it hurts and it becomes uncomfortable, but I am not going to let it beat me» (M5E1F61). The young woman gives credit to the disease for allowing her to grow in a unique way: «I am very grateful because it has made me grow enormously, more than I could have done in any other way» (M3E1F11).

Gains are derived after the arrival of lupus in the life of a young woman, there is a special change in those close to her, a better treatment emerges and the fact of feeling cared for is enjoyable, it is pleasant: «my mother has been more pampering, she is usually not so expressive, she is very cold, after the diagnosis, she is closer, more tender, more beautiful, cooler» (M4E1F30). In addition, she recognizes that the disease has allowed her to have a more spiritual vision: «I have begun to believe that there is something higher, I do not know what it is called, if it is God or whatever, but I have begun to believe in that» (M2E1F22).

Upon receiving the diagnosis of lupus, the young woman enters a path in which she recognizes the beginning of a constant learning, she finds herself and discovers things that she did not see before. The chronic and fluctuating nature of the disease reveals a long and complex path that will allow her to find herself day by day: «I have found many things that I did not know there were in me, you can give more and well, it will be a long process, I still feel that I can find more things about myself» (M2E1F28).

The woman with lupus points out the difficulty she faces when she adapts to the dynamics of the health system, in which, in addition to having to wait to be evaluated by a specialist, she invests considerable time in administrative procedures. In addition, she highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach by health professionals, affirms that humanized treatment, accompaniment and words of encouragement help her to cope with her situation in a better way: «How it helped me that a doctor, nurse, whatever, told me: how are you? How do you feel? . . . those two minutes that are spent selflessly for a person who is in a vulnerable state is something that changes many things, that it gives encouragement, which improves everything» (M3E1F3).

At the work level, the young woman diagnosed with lupus feels at a disadvantage compared to other coworkers when performing a job. When entering the classification list for a vacancy, she perceives discrimination for having a disease that brings with it certain limitations and sometimes she prefers to reserve her diagnosis: "I feel that it is a work factor that I would prefer not to say unless it is very active. If your lupus is calm I overlook it and I would not say it because I feel that you put yourself at a disadvantage when you say you have lupus» (M5E1F41).

In addition of the stigma in the face of the work opportunity, this woman emphasizes that she must face the restrictions derived from her condition, and that in turn complicate the performance of her role. She has been confronted with innumerable medical incapacities and in many occasions, even when she does not feel in optimal conditions, she must endure the symptoms of her disease to fulfill the role as a worker: «to be able to perform in a job it is super difficult, from the part of classification, in which they discard you at once to the physical point in which I cannot do it » (M4E1F47). The woman perceives that her new reality in the working environment will depend on the fluctuating nature of her disease and it leads her to think than other persons deserve more the opportunities in this field: «this will give rise to permissions to attend medical appointments, incapacities, expenses in the healthcare provider (EPS, for its acronym in Spanish), ... for them it is like an additional expense of money that is not worth it, being able to have another person who is not sick» (M5E1F42).

These limitations condition her productivity and also generate a great concern since the woman must respond for an immediate need for treatment which implies a high cost. The investment that she must make now in medicines, transportation and payment of moderating fees is perceived as an economic impact on the life of the woman with lupus: «this affects my pocket a little. . . a project that I had right now in November I cannot longer carry out it because I have invested it in medicines, in treatment» (M4E1F47); «I spend a lot of money in transportation, sometimes because my body actually do not allow me to move as easily as another person» (M5E1F50).

The new reality of the young woman with SLE leads her to be adapted to her condition and accept it as a part of her own being: «I took it as we are already here, there is nothing more to do, so it is time to read, be informed and see how I can face it in the best possible way» (M5E1F4); «Right now I see it as a friend because I also have to give him so that he can give me, if I don't give him he doesn't give me either [...]when I pay attention to it in the sense of taking care of myself, it also calms down» (M3E1F18); «for me is a motivation (the disease) to be happier and to help more the persons who are around me» (M5E1F48).

The woman perceives changes in her daily life, activities that she previously carried out in a simple way now require more planning, there are elements that have become her faithful company when it comes to going out and having control of the disease: «imagine going to a party, you cannot walk with a handbag as one normally does, no, I had to walk with the purse because I had to carry a lot of things, also to all the trips [...] I carried the blood pressure monitor, the pulse oximeter, and a few other things in case that at some point something happened to me» (M3E1F53). « At first I left the hospital taking exactly 36 pills, of different types and colors [...] changing from not taking an aspirin for nothing or a dolex, to having to sit down to prepare 36 pills every 4 nights, I sat down and cried, because it was very hard for me to know that I had to take all that [...] I never stop taking them but I hated it terribly (M3E1F52).

Living lupus through ties

The process of the disease has allowed the young woman to strengthen family ties. For her, this strengthening of ties is of great importance, she sees something positive derived from lupus: «I feel that the relationship between us as a family has become much stronger because we have become closer and I feel that there is also the opportunity to recognize that I am not alone» (M1E1F19).

The woman feels a constant accompaniment both from her family and her friends, the fact of not being alone gives her the strength to continue despite adversity. She identifies in those who surround her a support in which she can lean to continue her way, she recognizes an encouragement voice from which she is nourished: «they have been a very big support, knowing that they are here to accompany me. . . is like recognizing in them also a family, a support» (M1E1F37).

However, in some occasions she perceives that it is not easy to attend activities planned in advance with her peers because the physical limitations or the mood prevent her from doing it: «my friends make plans, they include me and then I am super encouraged... the day comes and "guys I can't", "I don't feel well", I don't tell them if it's emotionally or physically, I said I can't attend because it doesn't really motivate me for either of these two reasons» (M4E1F50).

It is difficult for her not to be connected with the affliction of those who provide her support; she perceives that there is a direct relationship between her integral well-being and the feelings of those beings. There are moments when the disease affects those close to me more: «I feel that the people around me find it harder, it is more difficult to see me sick and they feel more down for me, even when I don't feel so down» (M5E1F8). This is why, even if there is physical or emotional discomfort, the need to give more strength to others, rather than to herself, prevails.

Along her journey through life, the young woman with lupus encounters an obstacle that prevents her from creating new ties, she is uncomfortable with the fact of generating in those who love her a burden that they do not deserve: «is very difficult to generate social relationships with people because one reaches a point, or at least it happens to me, where you don't want to be a burden for other people, a burden not only as a physical person but also an emotional burden» (M3E1F3); For the young woman, the connection between her well-being and that of the people around her leads her to feel guilty, this reinforces her idea of feeling a burden: «I feel that when I am very negative with the lupus my energy is very heavy, I feel that this energy has to be in everyone, so if I am sad I want my mother and my sister to be sad, that they feel a little what I am feeling . . . then I say you are a burden because it is emotional, it is very heavy» (M2E1F16). «If a person gets attached to you and loves you in one way or another and you feel bad, then that person is also going to feel bad . . . I don't like to feel guilty about something like this» (M3E1F45). «Not wanting to overload people is super important . . . I have often hidden information (laughs) let's say my knee may be hurting a lot and I can't stand it, I will say: why should I tell him if he is not going to be able to do anything» (M3E1F43).

Although her family and friends give her their full support, she is afraid of creating emotional ties, a feeling of doubt about the possibility of having a stable partner invades her and she prefers to isolate her thinking about the matter. Sadness comes at the moments when her illness appears strongly, it is there where the belief that establishing a sentimental relationship would be complex is strengthened, once again, she does not want to be a burden: «I don't feel comfortable being with someone . . . the day I'm sick is like no, I don't deserve anyone, no one deserves to have this and no one deserves to live by my side seeing me like this» (M5E1F19). «I have locked myself away from people, precisely I at least walk in an EEE I got sick with the flu, it goes away, then a urinary infection, it goes away, then a wound in I do not know where, it gets infected, it goes away, yes? As well as in that stage of the disease [. . .] Then I don't want to be a burden to other people and it costs me a lot to open up with other persons, it is very hard for me to trust other people, but that did not happen before» (M3E1F34).

In the initial stage after the diagnosis, the shock in those who surround her leads them to overprotect her: "at first she wanted to have me in a quiet little box, that nothing would happen to me" (M5E1F60). The young woman feels that she cannot function normally and perceives a loss of autonomy; this increases in her the feeling of dependency and insecurity.

Unpleasant feelings persist, generated by the prejudices of people outside her experience. The woman is surprised by some derogatory comments under the erroneous thought of lupus as a contagious disease, in the same way she notices the disbelief of others regarding her symptoms: «when you are sick they do not believe you, it is because you are exaggerating or taking advantage of your illness . . . people expect that because you have lupus you have to be more down, sicker and with a pale face, but it is something that hurts every day, because undoubtedly almost every day I have a pain in some part of the body» (M5E1F18).

A feeling of sorrow is perceived in those who find out about her condition, she feels that she inspires pity and that is not what the young woman expects: «I was already tired that people treat me like a poor thing all the time. . . I do not need a poor little thing, yes?, it is not what I need» (M3E1F36).

Sharing her experience depends on her physical and emotional state. When the tide is high and the waves are strong, she prefers not to talk about her illness; she does not feel well doing it. However, when the lupus is asleep and the discomfort is not overwhelming, she wants to say that everything is going well: "there is like a duality . . . when I am not in the mood I do not like to be asked, but when I am well I like to say it" (M1E1F31).

Even, the recognition that there are those who share her suffering is born, she finds important the mutual support and she imagines the formation of a network with those comrades in struggle: «I feel that it is necessary for those of us who have this to realize that it is not only me who is suffering from it, but that there is also someone else . . . that someone else also feels what I feel and in a certain way can understand me» (M1E1F44).

Thus, the disease has represented for the woman great changes in her relationships with family, friends and partner, it is also worth highlighting the experience of these actors from the perspective of the young woman, she perceives that her way of establishing communication with them has been modified after the diagnosis, the dynamics and activities no longer revolved around a common taste, but rather to a physical and psychological need as a consequence of the condition. The new stage that she is living has implied a change in the thinking of those who surround her, the relationships between the members of her family improved, an environment of greater union and improvements in communication is perceived. In the same way, the union of the social circle to support and encourage her predominates, she recognizes that those who surround her also operate in a context in which the social events, extreme activities, trips and afternoons of study prevail, but in her case, those who accompany her must adapt to her new dynamics, the medical controls and the intervals with constant fluctuation: «In the family we have been more united [...] the family is too important and the relationship has improved, I feel that it is stronger» (M2E1F26); «it has been difficult for me to carry on the relationship in that situation [ . . . ] since I was diagnosed, I had several hospitalizations, then I know that also for him it was a very big burden to know that I was sick in the hospital, go to visit me, yes, all these things, at this age, let us say that it is not something that one expects» (M3E1F26).

The search for tranquility

To have a good quality of life, the young woman must undergo a series of procedures and treatments that make her feel dependent. The fact of being completely healthy and not having to take a single medicine changes to needing many more help to feel good: «it is living in exams, that they control you ... it is being aware all the time that you must take medicines to be well» (M1E1F18). However, she does not perceive it in a negative way, she accepts it because she understands that it is necessary and it provides her well-being.

The young woman seeks a reason for her diagnosis, she considers important to understand her outcome, the information she finds leads her to consider that past actions, experiences and feelings are related as the cause of her disease: «I feel that in certain part so much work. . . so much work-related stress activated it, activated my lupus» (M2E1F43). «When I was researching about what lupus was, what caused it, what were the causes that were proposed, I learned that it could be caused by the mismanagement of the emotions and as I feel that throughout my live I had a lot of hatred, a lot of resentment for someone» (M1E1F14). «I said: I was looking for it, yes, all my life I wanted to be sick and besides, as I did not take care of myself, I had bad habits, and then I said that I was hurting my body, what did I expect? To be perfect all my life? No. That led me to regret: Oh, why was I like that, why I did not value it, why I did not reconsider it» (M3E1F22).

In turn, she recognizes the emotional component of the disease and learns the importance of finding calm in the midst of misfortune. She understands that emotional balance is necessary for the management of lupus, she looks for what favors her: «I have become a little more aware of my body, of what is good for me . . . I have been aware that I need things that do good to my body, but also to my peace of mind and my spirit» (M2E1F9).

The young woman wants to make people understand that having lupus frames her within a different, but not abnormal, vital process: Ï am a normal person, I have to take care of myself, but I am a normal person (M3E1F37).

In the midst of the difficulties of the new way of life, day by day she thinks of a reason to continue. She remembers all those people who always accompany her; her relatives, her friends, and her partner. She compares herself with people in more distressing situations and is encouraged to go ahead: «that conversation I had with my sister when she told me "you are another, you are no longer the same as before and that is turning you off", it was like: what I am doing!, if you feel very empty, seek!, move around to seek what will fill you up» (M2E1F39).

Discussion

The findings of this study coincide with those of other investigations in young populations with chronic diseases, which highlight the limitations regarding study, work and the formation of a family; characteristic goals of the life period in which they are20. In addition, they are congruent with what is recorded in the literature regarding the diagnosis of chronic diseases in the period of youth10, as the diagnosis is experienced as a situational crisis in which the personal and professional life project is interrupted.

These results also support the evidence regarding the impact of SLE on the lives of patients. Thus, the young woman lives the disease similarly, with physical, psychological and social implications7,8. However, there are key aspects to highlight taking into account the differential period of the life cycle and the time of recent diagnosis of the participants.

In particular, about the experiences lived by young women with SLE, no record was found in the literature. Therefore, the results of this research were contrasted with other phenomenological studies that equally explored the experience lived with lupus, but in women of all ages21-26. From this, similarities that allow a greater understanding of the phenomenon were identified. But, likewise, certain novel findings that emerged from the present investigation stand out.

In relation to the category «my youth with lupus», there are aspects common with other studies such as the flowering of the innate strength from the diagnosis, some negative representations of the disease, the concern about motherhood, the impact of the treatments on the physical appearance, the desire to enjoy the present and the physical and psychological difficulties that the new condition implies on the life of the woman21-26. It is also discovered that the woman feels that she is aging early, which is related to the impact of the phenomenon on youth and represents an opportunity to continue with the research in the field.

In the essence of the second category "a reality that transforms itself", research shows similar results such as fear of the activation of SLE, lack of knowledge about the disease, efforts not to be defeated, the development of spirituality, difficulties for the execution of tasks and the need to adapt to a new role as a patient22-25. The novel descriptions address the express need to rebuild healthier lifestyle habits and the self-recognition process that is generated after the diagnosis. Favorable aspects that, according to the participants, contributed to the empowerment and acceptance of their disease.

The third category, «living lupus through ties», coincides with studies on the perception of the woman regarding the strengthening of previously established ties, the accompaniment in the process of the disease, the feeling of guilt for the shock she causes in those who are close to her, and the popular prejudices and judgments that the young woman faces22-25. The difficulty in generating ties, especially of an affective nature, stands out as a new finding, given the fear that «being a burden» for others means for the woman.

Finally, regarding the fourth category, «in search for tranquility», the effort to have experiences that provide tranquility and favor the management of the disease, as well as the self-imposition of limits, are common with other investigations22,23,26. The desire to normalize the disease and the need to define a reason to go ahead are conceived as novel findings.

Conclusions

In the first years of the diagnosis of SLE, the experience of being a young woman is influenced by internal and external factors, it implies a complete modification in her life dynamics and, although it leads to multiple difficulties, it also represents for her gains and opportunities. Coping mechanisms are developed in favor of adaptation to the new chronic condition, which reaches beyond the physical aspects and involves the mind, the spirit and the interpersonal relationships.

This research allowed us to elucidate key pieces in the experience of a youth with SLE and even more in the life experience of the first years with the disease, recognizing the value of the qualitative methodology for the approach to the phenomenon.

The implications of the findings make evident the need for multidisciplinary accompaniment from the healthcare team, since the latter plays a fundamental role during the stage of coping and acceptance of the new health-disease condition. In the first place, it is suggested to enhance those aspects that favor the experience of the young woman with SLE and, additionally, to direct educational interventions regarding self-care, adaptation to the change of life, adherence to treatment, management of symptoms and reduction of uncertainty.

Given the novelty of the research, the results contribute to fill a void in the existing knowledge since they bring out the significant aspects of the experience of living with SLE being a young woman recently diagnosed. It is recommended to carry out further qualitative research in order to contrast the findings of the present study and, in the same way, to explore the experience of the family member and particularly the experience of the young woman with SLE in the process of motherhood.

texto em

texto em