Introduction

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) is a chronic, immune-mediated bullous disease, included within the spectrum of mucocutaneous membranous pemphigoids (MMP). In MMP any mucous membrane, such as the trachea, larynx, esoph agus, vagina, anus or urethra can be affected, while when the compromise is essentially of the ocular conjunctiva receives the name of OCP, which is evidenced in 32-48% of the MMPs.1-5

It affects approximately 1.3 to 2 people per million inhabi tants, with a higher incidence in people between 50-60 years of age, although age variations between 20 and 80 years have been reported as well as a female predominance of 2-3:1. Different series estimate an annual incidence of 1 in 15,000 46,000 ophthalmological patients. The estimated prevalence in the United States was 1/20,000 to 1/60,000 in ophthalmol ogy consultations, and in the Hispanic population the number of reported patients is limited, so a low prevalence or an under-diagnosis or underreporting of the pathology is suspected. (3-13

Even though the etiopathogenesis of OCP is not exactly known, it is suggested that genetic and environmental factors could be involved, producing a type II hypersensitivity response. It is characterized by autoantibodies directed against the anchoring sites between the epithelial cells and the basement membrane, being the main site of involvement the epithelial basement membrane, unlike other bullous dis eases such as pemphigus. The antigen-antibody interaction leads to the initiation of the inflammatory cascade, producing an acute and chronic inflammation with scar formation. In the epithelial basement membrane, there is a deposition of IgA, IgG, IgM and c3 (IgG and IgA more frequently) and fragments of complement. This deposition is linear, unlike other entities that have a granular deposition. They have been described as antigens involved in the hemidesmosomal proteins, laminins, integrins and collagens. (3,4,6-8

In the acute phase, eosinophils and neutrophils are observed, while in the chronic phase, lymphocytes and fibroblasts are predominantly detected at the subepithelial level. Diverse cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, IL-17, TNFα, TNF-γ and colony growth factors have been observed in abundant amounts in the conjunctiva. IL-13, TNFα and the growth factor β1 have a profibrotic and proinflammatory effect, activating and perpetuating the survival of fibroblasts with the consequent deposition of collagen. Elevated levels of IL-8, metalloproteinases and myeloperoxidases9-11 have been detected in tear samples.

The diagnosis is often ophthalmological, but due to the autoimmune nature of the pathology it requires a joint approach with rheumatologists and immunologists. The understanding of the OCP has changed significantly in the last few decades. The contribution of basic sciences has been key in the description of the processes that participate in the immune response. Immunomodulatory therapy has allowed to preserve the vision and, in many cases, to prevent the fatal consequences for it in the course of the disease. The evolution is linked to early and timely diagnosis and immunosuppressive treatment, (3,4,6-8 and for this reason, knowledge of this pathology and the available evidence is substantial. The pro gression of the disease can lead to functional disability, such as corneal blindness, with an impact on the quality of life. On the other hand, the socioeconomic costs of patients with dis abilities, added to immunosuppressive treatments, reinforce the need for an early diagnosis and treatment. (14-16

The objective of this article is to make a review of the evidence published in the last 20 years, from 2000 to 2020, regarding the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treat ments available for patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid in different evolutionary stages, in order to update and famil iarize doctors in general with the subject.

Materials and methods

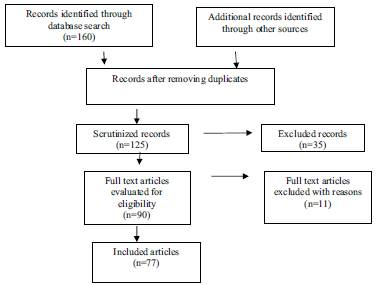

Narrative review of the literature. A literature search was con ducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Lilacs, Epistemonikos and SciELO on the evidence available in the last 20 years, from 2000 to 2020 in relation to the clinical manifestations, the diagnosis and the treatments available in patients with ocu lar cicatricial pemphigoid in different evolutionary stages. Full articles, with experimental and observational study designs, reviews, case series and case reports were included. Abstracts, repeated articles and those in languages other than Span ish and English were excluded. The search strategy consisted in searching controlled terms in the Virtual Health Library, Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) or Medical Subject Read ings, in English and in Spanish, with Boolean operators.

[Penfigoide Benigno de la Membrana Mucosa / Pemphigoid, Benign Mucous Membrane / Penfigoide Mucomembranoso Benigno / Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid / Penfigoide ocular cicatrizal / Síndromes de Ojo Seco / Dry Eye Syndromes]] AND [Terapéutica / Therapeutics OR Dapsona / Dapsone OR Sulfasalazina / Sulfasalazine OR Pentoxifilina / Pentoxifylline OR Hidroxicloroquina / Hydroxychloroquine OR Metotrexato / Methotrexate OR Azatioprina / Azathioprine OR Leflunamida / Leflunomide OR Tacrolimus / Tacrolimus Ácido Micofenólico / Mycophenolic Acid OR Ciclofosfamida / Cyclophosphamide OR Rituximab / Rituximab OR Inmunoglobulinas Intra venosas / Immunoglobulins, Intravenous OR Adalimumab / Adalimumab OR Etanercept / Etanercept OR Infliximab / Infliximab OR Certolizumab Pegol / Certolizumab Pegol OR golimumab/golimumab].

[Penfigoide Benigno de la Membrana Mucosa / Pemphigoid, Benign Mucous Membrane / Penfigoide Mucomembranoso Benigno / Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid / Penfigoide ocu lar cicatrizal] AND Diagnóstico / Diagnosis OR Técnicas de Diagnóstico Oftalmológico / Diagnostic Techniques, Ophthalmological.

[Penfigoide Benigno de la Membrana Mucosa / Pemphigoid, Benign Mucous Membrane / Penfigoide Mucomembranoso Benigno / Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid / Penfigoide ocular cicatrizal] AND Manifestaciones Oculares / Eye Manifesta tions.

The search was expanded with non-controlled terms in the gray literature such as: tofacitinib, baricitinib, tocilizumab, cyclosporin A, tracolimus and guides using Google Schoolar and OpenGray. Two abstracts were included in these cases.

The evaluation of the evidence was based on Lancet 200217, were it is stipulated, according to the design of the study, that the quality of evidence I is the one that comes from at least one randomized, controlled, well-designed clinical trial; is that obtained from a non-randomized controlled clinical study; II-2 is obtained from a well-designed case-control or cohort study, preferably from more than one study center or group; II-3 is obtained from multiple series of cases with or with out intervention and from important results of uncontrolled experimental studies; and III is obtained from the opinion of experts, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies or reports from expert committees.

Results

Clinical manifestations

The clinical presentation varies widely, from mild cases with slow progression and years of evolution to severe cases with torpid and rapidly progressive evolution to fibrosis, refractory to multiple treatments. The majority of patients have a slow evolution, with occasional exacerbations. (3,4,6-8

The onset can be unilateral or bilateral; and it usually involves both eyes. When it is unilateral, the contralateral eye is usually affected within 2 years. The OCP usually manifests initially as recurrent conjunctivitis, red eye or hyperemia, burning, pain, itching, lacrimation, photophobia, and foreign body sensation. It can evolve to a progressive keratopathy with neovascularization and conjunctivalization of the cornea, subsequently, appears the symblepharon, defined as a scar adherence that occurs between the conjunctiva of the eye lid and the eyeball, which can be visualized by depressing the lower eyelid and observing vertical conjunctival folds. In more advanced stages it evolves to ankyloblepharon, which is the fusion of the edges of the eyelids, generally in the area nearest to the outer canthus and with disappearance of the conjunctival sac. Dry eye of variable severity according to the stage is observed in OCP. The three layers of the lacrimal film (mucinous, aqueous and lipid) are altered. In late forms, the goblet cells of the conjunctival epithelium, which secrete mucin and help maintain the lacrimal layer, diminish or disappear. On the other hand, the scarring leads to the dysfunction of the Meibomian glands, fibrosis of their orifices and consequent alteration of the lipid layer, this being the one that most affects the evaporation and stability of the tear. (3,4,6-8,11-13,18

Conjunctival cicatrization can lead to entropion (inversion of the eyelid), trichiasis and distichiasis (eversion and abnor mal growth of the eyelashes, secondary to the cicatrization of the margin of the eyelid) and lagophtalmos (impossibility to close completely the eyelids, with difficulty in the distribu tion of the tear over the ocular surface.) The ocular exposure in turn leads to corneal damage, with erosions that together with dryness, distichiasis and lagophthalmos promote the appear ance of pannus, pseudopterygium and greater scarring with alteration of the vision to a variable degree and even blind ness. In turn, bacterial superinfection is also frequent. In very severe cases a corneal perforation can occur. In ophthalmological practice, the most frequent initial presentation and which raises the suspicion of the diagnosis is a chronic conjunctivi tis, with eye dryness, small conjunctival scars, distichiasis and narrowing or occlusion of the lacrimal points. (3,4,6-8,10-13,18-20

It has been suggested that even in cases in which the con junctiva appears white and without inflammation, there may be unobservable underlying inflammatory infiltrates (white inflammation, hidden inflammation), which could continue to stimulate the fibrotic process. (11,20,21

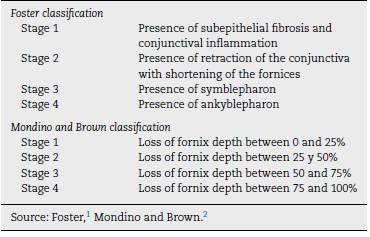

There are various classifications: Foster's1 is based on clin ical signs of progression, while that of Mondino and Brown2 is based on the evaluation of the depth of the inferior fornix. The compromise is usually asymmetric, and different stages can be observed in both eyes (Table 1).

The classification according to the severity is also impor tant: the presence of subconjunctival scarring and fibrosis is considered mild; moderate, the shortening of the inferior cul-de-sac of the eye; severe, the presence of symblepharon with horizontal involvement; and very serious, the observa tion of ankyloblepharon. Activity is evaluated by the presence of photophobia, ocular pain, conjunctival vascularization and hyperemia, edema and progressive cicatrization. (7

Detailed ophthalmological description of the different stages1,2

Stage 1: It includes conjunctival inflammation, secretions, epithelial sectors that stain with Rose Bengal and subepithelial fibrosis. This fibrosis is very subtle and it can be observed only with a slit lamp, it appears as very fine striae that surround the vessels, and these striations of abnormal connective tis sue are the ones that finally become contracted and will cause conjunctival retraction.

Stage 2: It is characterized by conjunctival retraction and shortening of the conjunctival cul-de-sac, the angle that the conjunctiva forms from the eyelid to the fornix is reduced, and the letters are used to describe the degree of shortening of the fornix: a) 0-25%, b) 25-50%, c) 50-75% and d) 75-100%.

Stage 3: Bands of connective tissue that give rise to symblepharon are added. The letters are also used to determine the percentage of horizontal compromise of the symblepharon: a) 0-25%, b) 25-50%, c) 50-75% and d) 75-100%. Trichiasis, distichiasis and decreased production of tears also appear with the progressive conjunctival retraction.

Final stage or 4: a severe dry eye syndrome, keratinization of the ocular surface and ankyloblepharon appear.

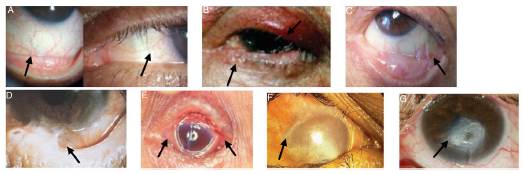

Images of patients with the clinical signs of the different stages of the disease are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Ocular manifestations in OCP. A) Conjunctival enanthema, stage 1 (Foster). B) Entropion and distichiasis. C) Subepithelial fibrosis, shortening of the inferior fornix and conjunctival symblepharon, stages 2-3 (Foster). D) More advanced symblepharon, stage 3 (Foster). E) Ankyloblepharon, stage 4 (Foster). F) Total epidermal growth on the ocular surface. G) Corneal perforation. Figures adapted from López Gamboa et al., (75 Espino-Barros Palau et al., (12 Chan et al., (4 Feizi and Roshandel, (76 Dart36 and Chirinos-Saldana et al. (77

Diagnosis

A complete evaluation of the patient, with anamnesis and physical examination, will help guide the diagnosis. The gold standard is the conjunctival biopsy, after which direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows a linear deposition of Ig or complement at the level of the conjunctival basement mem brane. The histopathology may reveal other entities, such as for example, granulomas in sarcoidosis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The biopsy must include two samples of tissue adjacent to an inflamed site, one for the routine anatomopathological study and the other for the DIF. In patients with involvement of other mucous membranes (MMP), initial biopsies should not be taken from the ocular conjunctiva. The sample obtained is stained with hematoxylin-eosin and with alkaline Giemsa. The inflamed conjunctiva shows infiltra tion of neutrophils, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and Langerhans cells. In advanced stages of the disease, the decrease or absence of goblet cells is notable. How ever, these findings are not pathognomonic of PCO and vary according to the stage of the disease and the sector in which the sample was taken. The diagnosis of certainty is estab lished with the DIF of the biopsy. For this, linear deposits of IgG, IgM and IgA and c3 must be observed in the basement membrane. The positivity of the biopsy varies between 20 and 67% according to the series. The use of immunoperoxidase in DIF-negative biopsies from suspicious patients increased the sensitivity from 52% to 83%.6-10,22,23

In some occasions, the biopsy may be inconclusive and the DIF may be negative. The Group for the Study of the Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid considers that if the ophthalmological criteria for MMP are met, but with an inconclusive biopsy, the case could be defined as MMP with negative immunofluorescence. (23,24

Regarding the laboratory studies, some antibodies present in certain cases of MMP, such as anti-laminin 5 and 6, anti-antigen 168kd, anti b4-integrin, anti-bullous pemphigo 1 and 2 and anti-collagen type VII have been detected, among oth ers. It is necessary to have more evidence of their usefulness in different cases. On the other hand, they are not very accessible in daily practice and their costs are very high. To date, there are no sensitive or specific laboratory studies available for the diagnosis and follow-up of the therapeutic response of OCP7,9,10,18,22-24

Other ophthalmological findings, such as eye dryness and alterations of the corneal epithelium, can be evaluated by means of various tests Among them, the tear break-up time (TBUT) is the most widely used to assess the stability of the tear film (time between a complete blink and the appearance of the first break-up of the tear film). A TBUT of less than 10 seconds is considered abnormal. Meanwhile, Schimer's test assesses the tear production by placing a strip of graph paper between the outer half of the lower eyelid and the bulbar con junctiva of each eye, keeping the eyes closed for 5 minutes. The proposed abnormal values vary between ≤ 5 mm and ≤ 10 mm. Other measures corresponding to dry eye are tear hyperosmolarity, considered abnormal above 308 mOsm/L. Stainings with fluorescein and its derivative, lissamine green, which stain the damaged cells and the filaments of lacrimal mucin, can be used to assess corneal epithelial defects. Finally, there are ana lytical tests such as the impression cytology and the detection of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, metalloproteinases and tumor necrosis factor in tears. (25,26

Among the differential diagnoses of cicatricial conjunctivi tis (OCP corresponds to 61% of the cicatricial conjunctivitis) are those after chemical burns, ocular surgical procedures, trauma, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis due to adenovirus, beta-hemolytic streptococcus, trachoma, diphtheria, dermatitis herpetiformis, atopic and drug-induced keratoconjunctivitis (drugs used in glaucoma), ocular rosacea, pemphigus vulgaris, among others. There are rheumatological pathologies that can manifest as cicatricial conjunctivitis; such is the case of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Sjogren's syndrome, scleroderma, lichen planus and sarcoidosis. It has occasionally been reported in associa tion with other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and autoimmune thyroiditis, among others. (27-29 OCP can also be a paraneoplastic manifestation. (30,31 On the other hand, some topical and systemic drugs can cause the appear ance of pseudopemphigoids, as a consequence of antigen exposure after tissue damage. Such drugs include topical pilocarpine, epinephrine, and echothiophate, as well as systemic practolol. (9,18,22,32-34

It has been reported a mean diagnostic delay of two and a half years, with a variation of up to more than 10 years. (18,22

Treatment

OCP is a systemic disease, and therefore requires local and systemic treatment according to its severity and evolution. The objective is aimed to control inflammation, facilitate repair and prevent scarring. Within the spectrum of mucous pemphigoids, those with ocular involvement are considered severe and high risk (like the tracheal or genital, among others), therefore, they require systemic treatment in all cases. (7,10,18,20,35

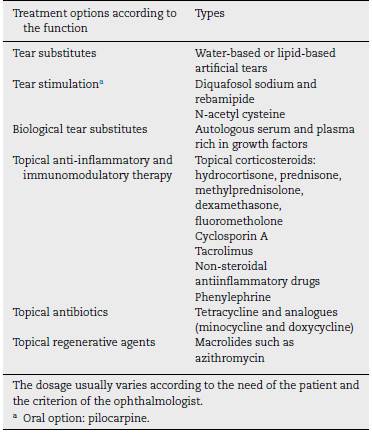

Topical therapy is used in addition to systemic treat ment. The prescription schemes are tailored to the needs of the patient and the clinical judgment of the ophthal mologist. In the Spanish consensus for dry eye diseases, modifications in environmental conditions, diet and drugs that could alter ocular moisture are recommended, along with the use of aqueous-based or lipid-based tear substitutes. Sometimes, tear substitutes are biological as is the case of autologous serum and plasma rich in growth factors. Top ical anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory treatments such as corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, phenylephrine, topical formulations of cyclosporine A and tacrolimus can be added. Tear stimulants such as diquafosol sodium, rebamipide, and N-acetylcysteine are also used3,15,25,26,32

It is possible to resort to the occlusion of lacrimal puncta with devices or cauterizing them if these devices are not tol erated, so that the tears are retained and providing relief. Dystichiasis can cause punctate keratitis, ulcers, and become complicated with bacterial superinfection. Hair removal is rec ommended every 2 or 3 weeks. Therapeutic contact lenses can be used or, in advanced cases is necessary to resort to surgi cal treatments. However, these interventions can cause more inflammation and progression of the condition. Blepharoconjunctivitis is frequent due to microbial colonization of the conjunctiva and the eyelid margins, thereby stimulating fur ther inflammation and keratitis. A prevalence of staphylococci has been found in patients with pemphigoid. It is advisable to carry out daily eyelid hygiene and treat Meibomian gland dys functions, using local and oral antibiotics when the condition requires it. If superinfection is suspected, antibiotic treat ment should be incorporated. (3,15,25,26,32 Topical treatments are detailed in Table 2.

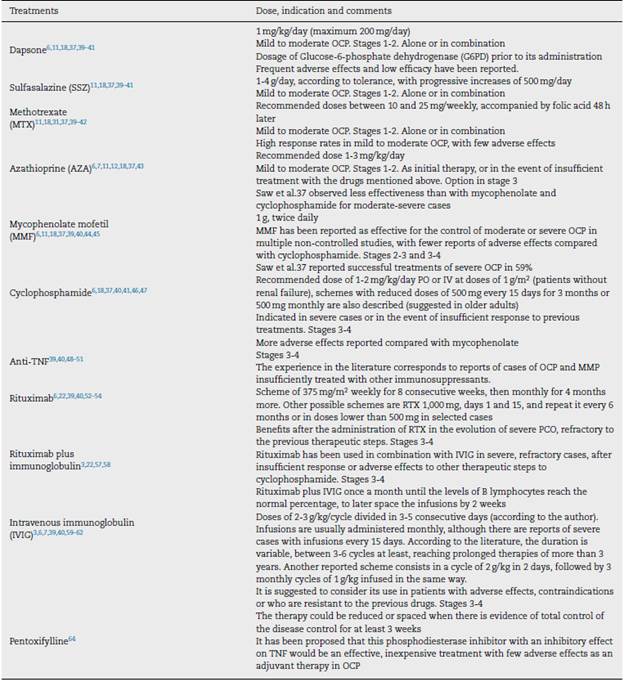

Systemic immunosuppressive treatment, has been classically established, according to the severity and in a stag gered manner. (3,7,8,13,36,37 Therapeutic changes or additions every 3 months have been proposed if the inflamma tory activity persists. (36,38 Thus, in mild to moderate OCP (stages 1-2) it is suggested to start with topical treat ment plus dapsone, (11,18,37,39-41 sulfasalazine (SSZ) 11,18,37,39-41 or methotrexate (MTX), (11,18,31,37,39-42 and thereafter con sider azathioprine (AZA) (7,11,18,37,43 or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (11,18,37,39,40,44,45 for moderate or moderate severe cases (stages 2 or 2-3). They can be used in combination (dapsone and SSZ in combination with MMF, MTX, AZA or cyclophosphamide, (18,37 or MTX plus AZA). (7 In severe cases (stages 3-4), MMF orcyclophosphamide, (18,37,40,41,44,46,47 and in very severe, resistant (recalcitrant) cases or in the event of adverse effects, anti-TNFs (etanercept and infliximab) (40,48-51, rituximab39,40,52-56 or IVIG. (7,22,39,40,57-63. Other reported treat ments are pentoxifylline, (64 hydroxychloroquine, (65 baricitinib and cyclosporin A66-69 in OCP and in MMP. In addition to the stages, it is important to consider in each case the disease activity and the clinical characteristics of the patient. (7 The systemic treatments and the available evidence in relation to the search strategy, according to study design are described in Table 3.

Regarding the use of corticosteroids, it is reserved for the acute control of the disease and while the full effect of the other immunosuppressive drugs is awaited. The doses and the route of administration are based on the severity of the case.

If the activity is moderate-severe, prednisone 1 mg/kg/day or pulses of methylprednisolone 500 mg/day for 3 days, with sub sequent gradual decrease in the dose should be considered. In mild or mild-moderate cases, variable doses between 5-40 mg of prednisone could be sufficient to temporarily accompany the other immunosuppressive drugs. It is suggested to use the minimum dose and for the shortest possible time to achieve control the symptoms. (7,36,37,40

Immunosuppressive treatment should be continued for at least one year after the stabilization of the dis ease, and subsequently a staggered decrease should be considered. (7,13,18,36,37,39,40 Sawetal. (37 observed that 41% of the eyes assessed (92/223) showed progression of scarring, con tinuing with minimal or mild inflammatory activity, which could not be eliminated despite immunosuppression, or after discontinuation of the treatment. Others reported scarring even in the absence of detectable inflammatory activity. (18,36 These findings suggest that the scarring process may continue despite the control of clinically visible inflammatory activ ity and that current immunosuppressive treatments may not achieve complete control of the pathology. One out of every 3 patients relapses within the years after the reduction or suspension of the immunosuppression, and therefore, close follow-up is necessary despite the remission. (18,36,37,39,40,68

The responses to the treatments are classified as follows: successful, when the disease remains quiescent, with white eye for at least 3 months from the start of immunosuppression; partially successful, when there is partial control of the inflam mation, but residual inflammation persists; failure, when there is an insufficient response to the drug, continuing with inflam mation, or in the event of suspension of the drug due to adverse effects. (3 Other definitions in the literature correspond to: remission, in the absence of progressive scarring and inflam matory ocular activity for ≥ 2 months; partial remission, when there is clinical improvement and control of the disease for ≥ 2 months; and long-term remission, when upon suspension of immunosuppressive treatment for ≥ 1 year, there are no detectable clinical signs of progression according to Foster's stages. (70,71

Discussion

In this narrative review, the evidence on the clinical presen tation is abundant, with varied manifestations. Regarding the diagnosis, there is agreement that the gold standard is the biopsy, but if it is negative or immunofluorescence is not avail able and the symptoms are characteristic, the diagnosis can also be suspected. The delay in the diagnosis and the insidious clinical symptoms which are potentially attributable to other more frequent pathologies at the onset of the disease, usually with recurrent conjunctivitis, red eye, ocular dryness, among others, stands out. However, the evidence in the litera ture hierarchizes the need for timely diagnosis and treatment to prevent ophthalmological sequelae.

In the last 20 years, the evidence for systemic treatment comes mostly from observational studies, and from some experimental. However, randomized clinical trials conducted prior to the search date that demonstrated the efficacy of the use of cyclophosphamide and prednisone in advanced stages of the disease stand out, (1,72,73 in addition to a Cochrane review on interventions in mucocutaneous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa. (74)Meta-analyses were not found according to the search strategy, only one randomized clinical study for pentoxifylline was found. According to the study designs, the literature presented corresponds mostly to quality II-III. On the other hand, a greater number of studies are observed in relation to rituximab and immunoglobulin compared to others used in previous stages.

Currently, treatments are based on the staggered strategy, but the progression with irreversible scarring and the pres ence of white inflammation question whether this approach is correct in all cases, or if stronger immunosuppression should be started early in certain patients to prevent the progression to fibrosis. There is not enough evidence yet to predict which patients will develop an aggressive course of the disease and whether they would benefit from a more intensive treatment since the beginning, mainly in those whose only manifestation is PCO without extraocular involvement. On some occasions, the recommendations are extrapolated from the evidence in the treatment of MMP, other ocular patholo gies such as uveitis, or other systemic autoimmune diseases, and therefore, it is necessary to expand the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic knowledge at the ophthalmological level. Likewise, it is probable to find in the literature cases with predominantly favorable outcomes and, therefore, an underreporting of those with negative outcomes. There is a wide variety of treatments whose indications vary accord ing to ophthalmological findings, however, there is still not enough evidence regarding the best recommendation in each case.

Due to the fact that the onset of the condition is usually nonspecific, patients tend to wander through different insti tutions and professionals, frequently consulting wards only in the event of increases in symptoms. The generally lim ited time of these consultations, as well as the impossibility of being followed-up by the same professional, lead to poor monitoring of the clinical picture. In turn, the difficulty for the performance of the conjunctival biopsy (high costs, lack of coverage by some health systems, need for pathologists spe cialized in the subject, etc.) causes a delay in the diagnosis and treatment. In severe cases, diagnosed and treated late, the progression of the disease can lead to sequelae and loss of vision, so the great medical challenge is early diagnosis and its corresponding treatment.

Conclusion

OCP is an infrequent pathology compared to other autoim mune diseases, of variable severity, mostly mild to moderate cases. The clinical presentation, often non-specific and the difficulties in the performance of the conjunctival biopsy have as a consequence a delay in the diagnosis and immunosuppression, which results in the progression of the disease with fibrosis. The available evidence on immunosuppressive treat ments, mainly in severe cases or refractory to initial therapies, is limited, with mostly uncontrolled studies, a reduced num ber of patients and short-term follow-ups.

The determination of risk factors for the progression to severe cicatricial disease and of serological markers or in conjunctival biopsies constitutes a challenge for the future, in order to predict which patients will develop a disease of rapid and aggressive progression and which will have a slow evolu tion and very rarely develop a mucosynequing disease.

The life expectancy of human beings has increased in the last decades, which makes them coexist with chronic dis eases. A high index of suspicion and knowledge on the subject is necessary to avoid definitive ophthalmological sequelae and improve the quality of life of the patients. The interdisci plinary approach between ophthalmologists, rheumatologists and immunologists stands out. The findings of the present narrative review explore the available evidence on the clini cal, diagnostic and therapeutic characteristics, most of them being applicable in daily practice. The validity of the studies should be interpreted based on the quality and design of each one of them. Finally, it is essential to continue the study of this entity, in order to improve the quality of the available evidence and thus optimize the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

text in

text in