Introduction

Journeys of migration abound in Los ríos profundos (1958). José María Arguedas projects this experience throughout the entire novel. This in itself should not be surprising for readers who have read Arguedas’s literature1. In fact, in all his literary works, the author presents the major characters in constant transition, which can be translated as a necessity to move around in an attempt to find peace. This migration from town to town is what identifies these major characters in the novel because they enrich others with their experiences as they travel, particularly in Ernesto’s case. Through Ernesto’s voice, Arguedas narrates and walks the reader through the Peruvian landscape, describing in rich detail people, cities, nature and towns as he passes by. Most compelling of all is Ernesto’s enthusiasm to embark on these trips which come to shape his personality and psychological maturity.

Analysis of migration in Arguedas’s literary work is vast and prevalent in the critical literature. For instance, Antonio Cornejo Polar’s article “Migrant Conditions and Multicultual Intertextuality” (1998) describes Arguedas’s literature as a “literature of migration.” 2 It is not only Los ríos profundos that communicates this migratory theme, but all Arguedas’s literary work, as Cornejo Polar states it. In fact, one can trace the theme of migration in Arguedas’s early short stories like Los comuneros de Ak’ola (1934), Los comuneros de Utej Pampa (1934), K’ellk’atay-Pampa (1934), El vengativo (1934) and El cargador (1935).3 Similarly, this theme would be common in Arguedas’s main novels like in Yawar Fiesta (1985), Todas las sangres (1970) and El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo (1971). It seems that Arguedas’s characters find peace when traveling, and not when living a sedentary life. For instance, one can mention Ernesto’s father, who is mostly traveling throughout the novel. Certainly, Ernesto displays this pattern as well because he is always in transitory displacement. More importantly, Ernesto matures as he travels throughout the novel.

Similarly, Ariel Dorfman, in his article “Puentes y padres en el infierno: Los ríos profundos” (1980), coincides in stating that Arguedas’s novel revolves around Ernesto’s mental development and his migration through the novel is crucial to acquire his maturity. As Dorfman explains:

En efecto, Ernesto, el narrador de la novela, va a enfocar aquellos meses cruciales en su existencia en que realiza el tránsito desde la infancia hasta la madurez, asumiendo por primera vez la compleja responsabilidad de hacerse ‘hombre,’ hombre como adulto, hombre como sexo, hombre como humanidad (91).

In other words, Dorfman describes that in Los ríos profundos Arguedas exposes the main character as a voyager, a person that must be in motion in order to become a “man,” a mature individual, even if he is not completely an adult yet.

Other scholars have seen Los ríos profundos as a “novel of growth.” In “Los ríos profundos como retrato del artista” (1983), Luis Harss claims that Los ríos profundos is an autobiographical portrait of sorts that specifically reports the artistic learning of the author (i.e., a Bildungsroman).4 Harss’s argument has its merits; however, Ernesto does not reflect that he is growing physically but mentally during the novel. This is what it seems as one reads it; nonetheless, it does not mean that he does not grow physically. It is just not noticeable in the novel. While protagonists in Bildungsromans develop both physical and mental growth, Ernesto’s development in the novel is more psychological, at least from what one sees. And even though he does not finish the boarding school, the time Ernesto spends there is enough for him to become mentally mature. He embarks on a journey of individuation, which will be explained at length throughout the development of this essay.

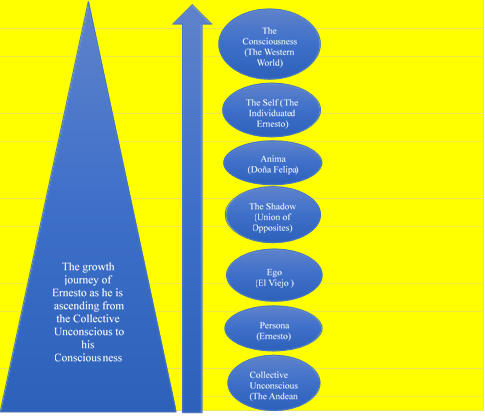

My approach to Los ríos profundos encompasses, on the one hand, the “migration condition” that Cornejo Polar (1998) attributes to Arguedas’s literature, and on the other, Ernesto’s mental growth, which Harss (1983) and Dorfman (1980) describe in their articles. Furthermore, I propose to view Ernesto’s migration and mental development through the lens of Jungian literary theory,5 specifically, by applying his concept of individuation (Jacobi 1967; Jung 1966). In this essay, I argue that Ernesto is going through an individuation process as he travels through the novel. As he begins his transition from the Andean world to the Western world, he also crisscrosses from the collective unconscious to his consciousness. Ernesto’s journey exhibits the painful but exciting voyage between the two realms of the psyche. Arguedas presents the following five Jungian archetypes in many ways and on many levels in this novel: persona, ego, shadow, anima and self. These archetypes are significant to the development of the main characters, especially Ernesto, who encounters and assimilates them as he narrates and journeys throughout the novel (Jung 2014). The process of individuation is not only an outer journey for Ernesto, but it is also a learning process, which allows his maturation by the end of the plot.

First of all, we must define individuation, a concept created by the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. Jolande Jacobi (1967) explains:

When consciously observed and guided, the individuation process presents a dialectical interaction between the contents of the [collective] unconscious and of consciousness; symbols provide the necessary bridges, linking and reconciling the often seemingly irreconcilable contradictions between the “sides.” Just as from the outset every seed contains the mature fruit as its hidden goal, so the human psyche, whether aware of it or not, resisting or unresisting, it is oriented toward its “wholeness.” Hence, the way of individuation-though at first it may be no more than a “trace”-becomes deeply engraved in the course of the individual’s life, and to deviate from it involves the danger of psychic disturbances (115).

Individuation is this conscious or unconscious journey that starts from the collective unconscious and ends in self-realization. Individuation is the process of maturing in a psychological manner. In order to follow Ernesto’s odyssey in the novel, let us follow a pathway that will track his phases in this individuation process. The structure will be as follows:

The Collective unconscious (The Andean World)

The Persona (Ernesto)

The Ego (El Viejo)

The Shadow (The Union of the Opposites)

The Anima (Doña Felipa)

The Self (The Individuated Ernesto)

Consciousness (Western World)

The Collective Unconscious (The Andean World)

The collective unconscious and the Andean world, specifically Cuzco, have something in common: both places are where the transformational process begins. Los ríos profundos starts its development in Cuzco, and Ernesto’s individuation process also initiates there. In other words, these places represent an ancient, ancestral connection with both the collective unconscious and the Andean world. In the words of Jung, “The collective unconscious contains, or is, a historical mirror-image of the world. It too is a world, but a world of images” (298). Therefore, the collective unconscious holds a history, a record where one can attain one’s past by searching and connecting clues, images, dreams and symbols with our past, present and even our future. In short, the collective unconscious is the archive where one can begin a pathway to personal and historical knowledge of oneself, which can be translated into personal growth.

In Los ríos profundos, Cuzco symbolizes the epicenter of the Andean World, the connection between the ancient and the present-day. Antonio Ureño points out that many ancient cultures around the world believe their homeland is located at the navel of the earth. The same can be said about the Inca capital: Cuzco is the world center of the Incan cosmology, the place where Ernesto initiates his transformational journey (127-128). In other words, Cuzco is the place where Ernesto connects the memories of his past with his present, and it is also the place where he gives a farewell to his father and begins his life-changing journey on his own. According to Tania Shirley Sáenz Cortez, “El paso de Ernesto por el Cuzco es de suma importancia porque ahí es posible que absorba toda la memoria de sus antepasados […]” (23). As one reads Los ríos profundos, most of the narrative develops in Abancay; however, the time Ernesto spends in Cuzco is fundamental because it is there where he connects with the ancient Andean world. In other words, Cuzco becomes the Jungian collective unconscious where Ernesto initiates his individuation process since he has attained a historical, cultural and personal framework.

The initiation of the individuation process arises from the deepest and darkest part of the collective unconscious (Jung 2014). It is not surprising that as Ernesto walks through Cuzco, this same sensation of darkness and despair floats in the atmosphere. He explains, “Entramos al Cuzco de noche. La estación del ferrocarril y la ancha avenida por la que avanzábamos lentamente, a pie, me sorprendieron. El alumbrado eléctrico era más débil que el de algunos pueblos pequeños que conocía” (Los ríos profundos 45). Although walking through Cuzco distresses and makes Ernesto apprehensive about the situation, there is still a strong connection with his descendants, a direct bond not only with his father but also with Cuzco, his culture and his ancestors. As soon as Ernesto enters Cuzco, he recognizes the persona in himself. He knows that he is wearing a mask that represents what the society and the ego want to see. His quest towards the conscious mind and the Western world would start as he arrives in Cuzco wearing this mask, a mask that identifies him as the child Ernesto as he goes through the first stage of this process.

The Persona (Ernesto)

The first stage of the individuation process is acknowledging the persona. At the beginning of his transformational journey, Ernesto gains the understanding that he wears a mask drawn by the outside world. Jacobi explains that the Jungian persona is based on an identity either recognized by the society or with which the ego feels better suited. In other words, the image we project is the image we are known for. For instance, we associate people with the job they do. The image of a doctor is the image we associate with such a person for life (37). In Los ríos profundos, Arguedas uses Ernesto as the persona, and we will remember him as such for life. Peter Elmore has noticed that “En el plano de la enunciación, el emisor adulto se vuelca hacia atrás, hacia una época ya vivida y solo indirectamente rescatable…” (78). This means the mature narrator has already integrated this persona within and, as he narrates, he has recognized this lived identity. He knows this mask has been transformed over the course of his journey. The narrator brings back the younger Ernesto as a remembrance.

Judith Butler’s performance theory endorses similar views; however, her analysis focuses on how gender is a performance and a product pre-constructed by society. As Butler affirms, “This style is never fully self-styled, for living styles have a history, and that history conditions and limits possibilities” (521). Society constructs people’s identities according to their gender, but society fails to observe beyond the body and into the mind that challenges these imposed identities. In terms of Butler’s performance theory and Jung’s persona, one can say that there is not a fixed identity and the gender, as well as the persona, in relation to Ernesto, will fluctuate according to the way the individual feels psychologically identified. As one notices, throughout his journey in Los ríos profundos, Ernesto challenges the identity he has been assigned. He knows he should pay respect to El Viejo because he is his uncle; however, instead, he confronts him. The child Ernesto is not accepting to be treated by his uncle like a kid or just like the rest of the “pongos.” If one looks closely, El Viejo treats Ernesto and his father like the rest of the servants, “pongos” that are under his commands. As they arrive to El Viejo’s hacienda, Ernesto explains:

Nos llevaron al tercer patio, que ya no tenía corredores.

Sentí olor a muladar allí. Pero la imagen del muro incaico y el olor a cedrón seguían animándome.

-¿Aquí? -preguntó mi padre.

-El caballero ha dicho. Él ha escogido -contestó el mestizo.

Abrió con el pie una puerta. Mi padre pagó a los cargadores y los despidió.

-Dile al caballero que voy, que iré a su dormitorio enseguida. ¡Es urgente! -ordenó mi padre al mestizo.

Este puso la lámpara sobre un poyo, en el cuarto. Iba a decirle algo, pero mi padre lo miró con expresión autoritaria, y el hombre obedeció. Nos quedamos solos.

-¡Es una cocina! ¡Estamos en el patio de las bestias! - exclamó mi padre.

Me tomó del brazo.

-Es la cocina de los arrieros-me dijo-. Nos iremos mañana mismo, hacia Abancay (Los ríos profundos 47-48).

In this fragment, the reader can witness that El Viejo ordered his servant to place Ernesto and his father in “el muladar,” a horse stable, not even inside the house. Ernesto and his father are treated without respect, like animals. As one continues reading, Ernesto’s father sounds humiliated and encourages him to leave the next day to Abancay. However, before leaving Cuzco, Ernesto faces El Viejo, the ego. In other words, Ernesto has acknowledged and gained the understanding that he is identified by his uncle as a kid; nevertheless, as he enters the first stage of the individuation process, this little Ernesto, this persona is not there anymore. He has started his transformation. El Viejo, the ego, cannot control Ernesto the same way he controls everybody in his four haciendas, and that is why after Ernesto acknowledges the persona, he will continue his path and challenge his ego in the next stage.

The Ego (El Viejo)

The second stage of the individuation process is confronting the ego. The ego shapes the personality that we want to convey to others in the outside world. He is the one in charge and no one can deal with him within the psyche. In other words, if the persona is the mask that others see on us, the ego is the one that decides if that mask benefits his own interests or not. Jung states: “The ego therefore has a significant part to play in the psychic economy. Its position there is so important that there are good grounds for the prejudice that the ego is the center of the personality, and that the field of consciousness is the psyche per se” (6). Considering how much authority the ego has over the psyche, in Los ríos profundos, El Viejo, Ernesto’s uncle, resembles the ego because he has power over everybody. In a certain way, the hacendado seems to own his workers. In fact, there is no one in any of his four haciendas who does not respect El Viejo. At one point, Ernesto and his father pay him a visit at his house, and he is impressed with the place his uncle lives. Ernesto describes the encounter as follows:

Yo entré rápido tras de mi padre.

El Viejo estaba sentado en un sofá. Era una sala muy grande, como no había visto otra; todo el piso cubierto por una alfombra. Espejos de anchos marcos, de oro opaco, adornaban las paredes; una araña de cristales pendía del centro del techo artesonado. Los muebles eran altos, tapizados de rojo. No se puso de pie el Viejo. Avanzamos hacia él. Mi padre no le dio la mano. Me presentó.

-Tu tío, el dueño de las cuatro haciendas-dijo.

Me miró el Viejo, como intentando hundirme en la alfombra (Los ríos profundos 60).

El Viejo owns an enormous house, and he has full authority in his place. Compared to the ego, he is the most important person in the whole Cuzco area. Arguedas seems to characterize hacendados in this way: avaricious and tyrannical. In Diamantes y pedernales (1954), the main character, Don Aparicio appears just like El Viejo. He is the richest person of the hacienda and everybody conceives of him as a patrón and protector. Arguedas projects the same image in El sueño del pongo (1965), where El Patrón, who is also one of the most powerful hacendados of the area, inhumanely mistreats and makes fun at the poor pongo. El Viejo, El Patrón and Don Aparicio fit the ego protocol discussed in this analysis, and this same concept can be applied to all these characters in Arguedas’s literary works. There is always one hacendado or someone with money and power who can be compared to the ego.

When Ernesto encounters the ego, El Viejo, he challenges him. El Viejo may be a powerful person, but Ernesto does not see him as such. In fact, he refuses to call him uncle. When Ernesto is questioned by El Viejo about his name, he simply replies, “Me llamo como mi abuelo, señor […]” (Los ríos profundos 60). Certainly, Ernesto is challenging the ego and, by not giving even his name to him, he is making the hacendado feel uncomfortable. In fact, it is not that Ernesto is ignoring him, but he is just not making his uncle feel as important as he thinks he is. Ernesto treats El Viejo as just another person who should be respected but not worshipped. When Ernesto does not give the response El Viejo wants to hear, he asks Ernesto, “¿Señor? ¿Qué no soy tu tío? (Los ríos profundos 60). At this point, Ernesto does not say anything, but he thinks about the power El Viejo has and the way he and his father have been treated by him.

During the encounter with the ego, Ernesto knows what El Viejo can do; nevertheless, he plays by his own rules. In Jacobi’s words, “In order to arrive at a harmonious [state of mind] of these parts of the psyche, one must first of all distinguish and delimit them from one another” (17). This is exactly what Ernesto does; he demarcates himself from his uncle in a very respectful manner, without forgetting that his uncle is the one in the position of power. Although the ego never gives up his power easily, as we see and notice later in the novel with the characters Lleras and Gerardo, Ernesto deals properly with him and understands his supremacy. In other words, the ego controls the psyche, and El Viejo owns literally everything in his four haciendas, including his workers. In a sense, through El Viejo, Arguedas represents the legacy of the encomienda system, in which a few hacendados control huge latifundios. Returning to Ernesto’s individuation process, he not only deals with the ego, but he also integrates the shadow during his odyssey.

The Shadow (The Union of the Opposites)

The third stage of the individuation process is confronting and embracing the shadow. As Ernesto continues with his journey of mental growth, he encounters the shadow and integrates it within him. But what is the shadow? Why would it be so important for Ernesto to understand the shadow and work with it? Jung asserts that the shadow has both negative and positive qualities which dwell on one’s own psyche but are projected onto others: “Projections change the world into the replica of one’s own unknown face” (9). Therefore, the understanding and unification of these opposites will help to reconcile this internal divide. Without the integration of these opposites, the individuation process would not be possible. Deborah Ford simplifies the complexity of the shadow by saying, “When we suppress any feeling or impulse, we are also suppressing its polar opposite. If we deny our ugliness, we lessen our beauty. If we deny our fear, we minimize our courage. If we deny our greed, we also reduce our generosity” (11). In other words, recognizing the good and the bad that one can be is the best way to understand our shadow and its attributes. In Los ríos profundos, we can see Ernesto coming to understand the virtues of the shadow as he integrates both, negative and positive, traits from his world.

The integration of the shadow occurs all along the novel; the incorporation of opposites is one of the central themes of the text. The narrative of Arguedas, as Ana Lambright avers, employs “Figures, spaces and objects that mediate the oppositions (Spanish/Indigenous, culture/nature, masculine/feminine, the dominant/the subaltern)” (5). Arguedas, in the case of Ernesto, could have only used Spanish to describe the huaynos;6 nonetheless he decides to integrate both languages. There are instances in which the juxtaposition of opposites occurs in the text, yet the following example grabbed my attention: Ernesto describes one of the symbols of the Andes, the condor, integrating both Quechua and Spanish languages. During the month of May, the Indians sing the “huayno guerrero:”

Killinchu yau, Oye, cernícalo, Wamancha yau, oye, gavilán,

urpiykitam k’echosk’ayki voy a quitarte a tu paloma, yanaykitam k’echosk’ayki. a tu amada voy a quitarte.

K’echosk’aykim, He de arrebatártela K’echosk’aykim he de arrebatártela

apasak’mi apasak’mi me la he de llevar, me la he de llevar, Killincha ¡oh, cernícalo! wamancha ¡oh, gavilán! (Los ríos profundos 74).

In this huayno, Ernesto integrates Spanish and Quechua to unify these opposite poles. He has incorporated both languages and has presented them proudly in this huayno. While Ernesto has embraced the richness of Quechua and uses it to his advantage in most of what he describes in the novel, others are even ashamed of not only the language but also the Indian people. For instance, this occurs when Valle says to Ernesto, “-No tengo costumbre de hablar en indio-decía-. Las palabras me suenan en el oído, pero mi lengua se niega a fabricar esos sonidos. Por fortuna no necesitaré de esos indios; pienso ir a vivir a Lima o al extranjero” (Los ríos profundos 131). Unsurprisingly, Valle vilifies and derides what he is part of because he, unlike Ernesto, has not come to terms with his shadow.

In order to discover the hidden power of the shadow, what Valle must do is shadow-work, as Connie Zweig and Jeremiah Abrams might recommend. They suggest looking at other people as if they were mere mirrors because we project onto them all positive and negative traits within us that we have not made conscious yet (272). Ernesto has recognized and made conscious these opposite poles. He has made peace with everything that surrounds him and, at one point, he expresses this satisfaction: “¡Al diablo el “Peluca”! -decía-. ¡Al diablo el Lleras, el Valle, el Flaco! ¡Nadie es mi enemigo! ¡Nadie, nadie! (Los ríos profundos 140). Nothing seems to bother Ernesto because he is learning how to own his shadow.

The author of Los ríos profundos also understood and integrated magnificently these opposites within him. In his acceptance speech for the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega award in 1968, Arguedas explained this concept clearly when he said, “Yo no soy un aculturado; yo soy un peruano que orgullosamente, como un demonio, feliz habla en cristiano y en indio, en español y en Quechua” (Arguedas, El zorro de arriba… 12). Clearly, the author of El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo also had an encounter with his own shadow. The integration of the shadow is an extremely important stage in the individuation process; nevertheless, in order to complete this process, Ernesto must recognize the anima and the self.

The Anima (Doña Felipa)

The fourth stage in the individuation process is integrating the feminine side that resides within men. As Ernesto keeps moving along on his journey, he will encounter his feminine side, his anima. In the words of Jung, “Whenever she appears, in dreams, visions, and fantasies, she takes on personified form, thus demonstrating that the factor she embodies possesses all the outstanding characteristics of a feminine being” (13). Given Jung’s statement, therefore, it is not surprising to witness the visions of the anima that first appear in Ernesto’s chimeras early in the novel. Since he is in the process of maturing, Ernesto’s first image of a woman, or his anima, comes to his mind at the boarding school. As he thinks about the travels with his father, he remembers a tall girl with a beautiful face. She was thin and small, with blue eyes and braids. This girl used to live in a town, a wild town from “las huertas de capulí” (Los ríos profundos 109).7 Ernesto fantasizes as he remembers this girl from his early childhood. This is the first time in the novel that Ernesto begins to contemplate a woman in a more vivid form; therefore, considering Jung’s assertion, he is indeed starting to recognize his anima. While this first revelation of his anima was more of a daydream, further in the novel Ernesto experiences a physical and tangible encounter with Doña Felipa, who, in my opinion, represents his anima in full.

Doña Felipa, in Los ríos profundos, is the first physical woman towards whom Ernesto feels a strong connection and admiration. Doña Felipa is also one of the leaders of the chicheras that starts the rebellion against the authorities who fail to deliver salt to the people from the surrounding towns. Right from that moment, he sees the way she leads the entire community, striving to get the salt, and Ernesto bonds spontaneously with Doña Felipa. Opinions differ, though, about the manner Ernesto perceives and idealizes her. For instance, Roland Forgues claims that within the unconscious of Arguedas, Doña Felipa is perceived as a “potential mother.” Here, Forgues makes a reference to Arguedas’s personal biography, emphasizing that the author turns his frustrated personal love and projects it onto the indigenous community (1989). Similarly, Peter Elmore shares that “Huérfano de madre, no sorprende que el púber vea en doña Felipa a una figura materna y protectora” (83). Indeed, neither Ernesto nor Arguedas grew up with their biological mothers; nonetheless, if that would have been the case, according to Elmore and Forgues, then the author could have written Los ríos profundos, complementing Ernesto with a mother in order to compensate what Jung calls the “mother imago” (14). From our point of view, Ernesto finally faces his anima, his feminine side, which will make him move forward with his individuation process.

Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge Doña Felipa as Ernesto’s anima. It is not a coincidence that she becomes omnipresent in his life from the time he sees her at the salt revolt until almost the end of the novel. As Josef Goldbrunner states, “As the dark, emotional, pregnant and creative principle, the anima is also the relation to the inner world […]” (123). Ernesto’s integration of his anima within his inner world is outwardly expressed as he projects it onto Doña Felipa. Her integration is so prevalent that, at one point, explains Lambright, Doña Felipa is almost worshipped by Ernesto. She is idealized as a goddess, or at least close to one. Her presence is so significant in Ernesto’s life that he compares her with the river, which is, in a certain way, what gives life (130). The exceptional transformation of Ernesto, now that he has integrated his anima, will be reflected on the self, the final destination of his developmental journey.

Self (The Individuated Ernesto)

As the journey has almost been fulfilled, Ernesto now has acknowledged the persona, ego, shadow, and anima. The acknowledgment and integration of these archetypes is essential to the construction of the self. In order to keep the self in equilibrium, the persona, ego, shadow, and anima must be attuned to the self. Jacobi explains that “The self is always there, it is the central, archetypal, structural element of the psyche operating in us from the beginning as the organizer and director of the psyche processes (50). In other words, as the individuation process reaches completion, the self operates more freely because it is working in conjunction with the other archetypes. The self is in full control and harmony with the rest of the archetypes, which make this perfect balance in Ernesto’s individuation process.

In Los ríos profundos, Ernesto, as the self, has also integrated all these elements throughout his journey. However, this last stage of the individuation process does not happen easily, as nothing is straightforward on this transformational journey. In fact, Ernesto still needs to go through the last challenge of his journey. He has to face typhus as part of the redemption of his individuation. Just as “the plague becomes a spiritual metaphor of Opa’s liberation from sin and purification of her abused body” (Jimenez 230), for Ernesto, this ritual happens in the same manner, except that he does not pass away as Opa did. Instead, he is fully transformed.

Ernesto goes through a remarkable ritual, as he becomes individuated. Since he saw La Opa agonizing, the priest thinks he is infected with typhus. However, this is not the case, as he further explains what the priest commanded, “Desde afuera ordenó que me desnudara. El portero me limpió el cuerpo con un trapo; me cubrió con una sábana y me llevó cargado a la celda todavía deshabitada del Hermano Miguel” (Los ríos profundos 279). Ernesto has been somehow treated by the priest and the concierge from the boarding school. After this ritual, Ernesto has completed his individuation process. At this point, he is ready to leave the town because he is now immune to typhus. He even surprisingly expresses, “[Tuve] un llanto feliz, como si hubiera escapado de algún riesgo, de contaminarme con el demonio” (Los ríos profundos 281). However, Ernesto is not only ready but conscious about what is happening to him and he is also aware that, as he is leaving the town and the boarding school, he is embarking towards the Western World where the novel and his journey end.

Conscious Mind (Western World)

A new journey is about to start, and Ernesto has already developed psychological maturity. The symbols and signals aim towards the Western World and, as he is waking up in the morning, ready to leave the boarding school, Ernesto says:

Estaba despierto cuando el reloj dorado del Padre Director tocó una cristalina marcha europea, una diana que repitió tres veces.

Prendí la luz y me acerqué al reloj. Representaba la fachada de un palacio. Sus columnas terminaban en capiteles con figuras de hojas. Seguía tocando. Me vestí rápidamente. Esa música me recordaba la marcha de la banda militar; abriría delante de mis ojos una avenida feliz delante a lo desconocido, no a lo temible (Los ríos profundos 305).

This makes us understand that he is not afraid of going away, of taking another long trip. He might be going where his uncle lives, as some suggest, but it is an uncertain path that he is about to take. What is certain, though, is the fact that he is leaving the town of Abancay with a mature mind, although he is still an adolescent. We do not know exactly where he is going but, by the traces he has left behind, one can suggest that he is going to discover the Western World. Ernesto has grown over the course of his experience at the boarding school, as Elmore, Dorfman and Harss claim, but more importantly, he has also gone through the process of individuation.

Conclusion

After having gone through the individuation process, over the course of his journey, Ernesto has matured psychologically. While Harss, Dorfman and Cornejo Polar have viewed Ernesto’s journey and growth from outside, I have analyzed this journey and growth from within his mind: a journey from the collective unconscious to the conscious mind. Throughout this analysis, we have observed the development of Ernesto as he progresses in Los ríos profundos and the way he ascends from the collective unconscious to his conscious mind. This psychological development in the main character’s journey takes time and, as one has witnessed through the entire text, it is a long process. It is not only the process, but also the different stages or archetypes through which Ernesto had to go to in order to become conscious about his reality. The individuation process can only be attained by experiencing these phases and archetypes, and since it is a process, each phase must be dwelled through. Jung’s literary theory has given us different tools to see José María Arguedas’s literary work from a fresh perspective; however, I think there is much work to do. While I have only conceived the individuation process, Arguedas’s work can be studied through Jung’s literary theory and analyzed in a similar way by using one of the archetypes mentioned in the article. However, I believe the shadow archetype could be applied to almost all the novels of Arguedas because this concept unites opposites just like the Quechuan concept tinkuy, which also symbolizes the union of complementary counterparts. As one reads Los ríos profundos, Diamantes y pedernales, El sueño del pongo, Yawar fiesta and other major works by Arguedas, it is noticeable that he includes opposite poles in almost all the storylines. Therefore, considering that Jung’s literary theory has rarely been applied to Arguedas’s narrative work, it could provide a fresh psychological perspective on other novels, just as it has with Los ríos profundos