Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de Derecho

Print version ISSN 0121-8697

Rev. Derecho no.45 Barranquilla Jan./June 2016

The "constitutionalization" process of the international environmental law in Colombia*

El proceso de "constitucionalizacion" del Derecho internacional ambiental en Colombia

Alejandro Gomez - Velasquez**

Universidad EAFIT (Colombia)

** Magister in Constitutional Law and LL.M in International Legal Studies, Associate Professor in Public Law, EAFIT University.

Correspondencia: carrera 49 no. 7 Sur-50, Medellin (Colombia). agomezv1@eafit.edu.co.

Fecha de recepcion: 22 de octubre de 2014

Fecha de aceptacion: 7 de mayo de 2015

Abstract

The Colombian Constitution has a particular interest for the environmental issues. As part of it, the Constitutional framework includes the possibility to introduce international environmental norms to the Colombian legal system. As a general rule, the Constitution provides a process of ratification for international norms to make them part of Colombian legal system. But exceptionally, the Constitutional Court has recognized that some international norms could make part of the Constitution and at same normative level. This doctrine has been called as "block of constitutionality". In recent rulings, the Constitutional Court has held that some international environmental norms made also part of the Colombian Constitution and share the same legal hierarchy. This is precisely the case of the international environmental norm of the Precautionary Principle, for whom the Court has held expressly that it has a Constitutional status. Due to the implications of this recent holding to the Colombian and international environmental law, the present paper addresses the legal background of these jurisprudence, places it in a comparative perspective and suggests some perspectives from this seminal doctrine.

Palabras clave: Constitution, International Environmental Law, Precautionary Principle, Colombian Constitutional Court.

Resumen

La Constitution Politica de Colombia tiene un interes particular en los asuntos ambientales. Como parte de ello, el marco constitucional incluye la posibilidad de introducir normas ambientales internacionales al sistema juridico colombiano. Como regla general, y una vez hayan surtido el proceso que la Constitution establece, estas normas entrardn al ordenamiento juridico national y tendrdn el mismo rango que una ley de la Republica. Sin embargo, excepcionalmente, la Corte Constitucional ha reconocido que algunas normas del derecho internacional pueden llegar a ser consideradas parte de la Constitucion y, por ende, tienen su mismo rango normativo. Esta doctrina ha sido llamada "Bloque de Constitucionalidad". En fallos recientes, la Corte Constitutional ha sostenido que algunas normas ambientales internacionales hacen parte de la Constitucion, a traves del Bloque de Constitucionalidad, y por ende tienen su misma jerarquia normativa. Este es el caso particular del principio internacional ambiental de Precaution, el cual para la Corte ha sido "constitucionalizado". Debido a las implicaciones de esta reciente pero ya consistente posicion jurisprudencial para el derecho colombiano e internacional, este articulo aborda el contexto de dicha jurisprudencia, la ubica desde una perspectiva comparada y sugiere algunas perspectivas para esta incipiente doctrina constitucional.

Keywords: Constitution, Derecho International Ambiental, Principio de Precaution, Corte Constitutional.

INTRODUCTION

Most environmental problems are global and trans-boundary issues that require international and cooperative solutions. International environmental law is the body of norms that refer to the cooperative and inter-governmental strategies to make front to the global environmental challenges. However, it is not a secret that this cooperative logic is not working on the speed and depth that the environmental issues require, due, in part, to the force that the principle of State sovereignty still has in international relations.

The effects of this tragedy can be evidenced in two different situations. On one side, the self - interest logic of the States does not allowed the creation of an adequate international environmental system that will be able to address all environmental challenges. On the other, the state-centric logic has created a gap between the already existing international environmental norms and its effectiveness. This second situation refers to the effectiveness of the international environmental law to solve the underlying environmental problems, and how some states are reluctant to implement it and comply with international obligations even when they previously have adopted or ratified these norms.

This paper will address this last particular issue. Doing so, it is clear that the effectiveness of the environmental international law will depends on an adequate "domestication" (Hunter, Salzman & Zaelke, 2006) process of the international obligations that bind not only the State's behavior, but also citizens and private entities. In rule of law States, the incorporation or "domestication" process implies the technical question on how these norms will become part of the legal system of the State and which the legal level of these new norms is in the normative hierarchy. Both issues have significant relevance because, according to the procedure and the highest level that a norm has in a constitutional system, the compliance and effectiveness of the norm must increase, at least in theory. Therefore, knowing the mechanisms of "domestication" of the international environmental law and particularly the normative level that these norms would occupy in a domestic legal system could have a direct relation with the level of compliance and thus effectiveness of the international norm.

From a comparative perspective this is a current issue. The increasing globalization of environmental law and the harmonization of international and national environmental laws impose a duty on States to design, develop and implement policies, and pass legislation that integrate the proliferating environmental norms and principles into their legal systems. However, the best ways to do that, the role of the public institutions, and the normative level of the international norms in the municipal systems are ongoing questions without a definitive answer. Good examples of this issue are the current discussion in Europe about the direct application of international environmental treaties by the European Court of Justice (Marsden, 2011), the recent constitutiona-lization of some environmental principles by the French Parliament through the Charter of the Environment (Faisini, Llie & Artene, 2012), or the judicial decisions in India and in Pakistan to incorporate some international environmental norms to its legal systems (Jobodwana, 2011)).

In this reasoning, Colombia is a constitutional and rule of law State. The Colombian Constitution put special attention to the environmental issues and thus has been considered as an "Ecological Constitution". Also, the Constitution establishes a mandate to the State to internationalize the environmental relations and provides a special procedure for the approval and ratification of the international norms. From this constitutional framework, in principle, the international norms ratified by Colombia will have the normative level of an ordinary law, and therefore, shall irradiate the content and interpretation of norms of equal or lower level, according to the legal hierarchy.

However, in recent rulings, the Constitution Court has held that some international environmental norms, which initially were conceived as statutory provisions, nowadays have a constitutional-based hierarchy and have been used as a constitutional parameter both to abstract and concrete constitutional reviews. With this decision, the Court took a similar position like in Europe, India or Pakistan in which the judicial authorities have taken a preponderant role in the incorporation of international environmental norms to the municipal systems. This novelty position of the Court has significant relevance for the Colombian legal system. From a normative perspective, if a norm is conceived as a constitutional-based-principle, then it implies, at least, that this provision must irradiate the content and interpretation of the other norms of the lower level. Also, with the constitutional recognition of these international environmental principles, they become constitutional parameters and their compliance and effectiveness could be claimed by any constitutional mechanism. These are some of the consequences, among others.

Hence, the purpose of this paper is to understand the new holding of the Colombian Constitutional Court about the "constitutionaliza-tion" of some international environmental principles. Doing so, this paper will pay special attention to the constitutional framework, the legal arguments and the cases that the Constitutional Court has used to hold its position. With this purpose in mind, the first section of this paper will present the constitutional framework of the environmental law in Colombia. It will be focused on the content of the rules that compose the "Environmental Constitution" in Colombia, and then on how the constituent addressed the environmental issue from a legal perspective.

The second section will address the processes of "internationalization" and "constitutionalization" of the environmental law in Colombia. The first part will analyze the constitutional regulation of the international law and how and in which normative level an international rule could be binding to the Colombian State. The second part will be focused on Article 226 of the Constitution, which mandates for the internationalization of the environmental relations. The effects of this mandate will also be analyzed. And finally, this section will present and conceptualize the preliminary phenomenon of the judicial "constitutionaliza-tion" of the international environmental law made by the Constitutional Court in recent jurisprudence.

The third section will present the case of the Precautionary Principle as an example of the process of "constitutionalization". The first part of this section will be focused on the content of the principle and how it was legally implemented in Colombia. Then, the second part will analyze the jurisprudential line, in which the Constitutional Court has changed the conception of this Principle in the Colombian legal system, from a statutory-principle adopted by Congress in an ordinary law to a "constitutionalized" principle.

Lastly, the relevance and convenience of this paper is based on the significant changes that may occur because of this novelty and a preliminary position of the Constitutional Court about the hierarchy of the international environmental norms in the Colombian system. If the Court's position prevails and is later reiterated by other international environmental rules, the impact will be significantly improved not only in the compliance, but also in the effectiveness of the international environmental law in Colombia

THE CONTENT OF AN ECOLOGICAL CONSTITUTION IN COLOMBIA

The Colombian Constitution as a Ecological Constitution

In Colombia, the environmental issue was a serious concern in the Constituent Assembly of 1991. At that moment it was considered that no modern Constitution could ignore the importance of including in its contents the treatment of this vital issue, not only for the national community, but also for all humankind. In addition, the Assembly considered that the environment was a common heritage of humanity and that its protection ensures the survival of present and future generations. About this issue, on the records of the National Constituent Assembly of 1991 it was stated,

The protection of the environment is one of the modern State purposes, thus, all State structure must be enlighted by this purpose and must tend to it realization. .. .The environmental crisis is, equally, a civilization crisis and it redefines the way we understand the relations between mankind. Social injustice results in environmental imbalances and that, in turn, reproduces the conditions of misery.

As a response to this concern, the protection of the environment issues occupies a central spot in the Colombian Constitution. At least, 49 constitutional dispositions are related to this matter and to the mechanisms of its protection. This wide interest to the environment had made that the Constitutional Court used the term "Ecological Constitution" to refer to the Colombian Constitution, and more precisely, to the whole set of superior rules that established the relation between the national community and nature, and which procure for its conservation and protection (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1998).

From the content of the "Ecological Constitution", it is possible to identify three different approaches to the environmental issue: one ethical, one economic and one juridical. From the ethical approach, the Constitution creates a bio-centric principle in which the mankind is conceived as part of the nature, recognizing that both elements have significant value not only for the present generation but also for the future ones (Amaya, 2010).

From an economic perspective, the Constitution conceived that the production system couldn't extract resources and produce waste un-limitedly. Those activities must be bound to the common interest, the environment, and the cultural heritage of the nation. Accordingly, these activities must be under the general direction of the State. However, this economic approach does not suggest a strictly conservative perspective of the environment because it tries to harmonize this value with the right to development, indispensable for the satisfaction of the human needs, imposing only the necessary and proportional restrictions for the protection of the environment. In this sense, the Constitution adopts expressly on Article 88 the economic perspective of the "sustainable development" (Garcia, 2003). In this regard, the Constitutional Court (2008) has said,

It is evident that the social development and the environment protection impose a univocal and insoluble treatment that progressively allows to improve the living conditions for the people and social welfare, but without affecting or decreasing irrationally the biological diversity of the ecosystems because those serve not only to the productive production, but also, to the conservation of the mankind.

From the legal approach, the State not only must protect the dignity and liberty of the citizens from others, but also from the threat that represents the exploitation and depletion of the natural resources. Doing so, the State must elaborate values, principles, norms and regulations in which the protection of collective values, like the environment, shall prevail from the individual ones. This legal perspective is developed in the Constitution by three different mechanisms: (i) the creation of a constitutional principle about the protection of the environment that must irradiate the legal system; (ii) The provision of the right to enjoy a healthy environment; and (iii) the imposition of particular obligations to the State and to citizens to protect the environment.

The Constitutional principle of the protection of the environment

In the "Environmental Constitution" the protection and defense of the environment is a constitutional principle. Therefore, this principle must irradiate all the Colombian legal system, making that any action of the State or any normative disposition must respect this principle as long as possible, and in accordance with the other constitutional principles. Moreover, this principle will constitute a constitutional parameter to evaluate the adequacy of a norm or an act of the state in relation to the Constitution, both in a concrete or an abstract constitutional review.

Regarding the content of this principle, it is important to highlight that from the economic approach made in the Constitution, a pure conservative perspective is overcome and the idea of sustainable development is explicitly provided in the Constitution. Thus, the principle of protection must include a balance between, on the one hand, the social needs, the right to development and life quality; and on the other, the preservation of the environment, bio-diversity and ecosystems. Only in this sense the idea of a "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of the future generations to meet their own needs" could be achieved (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). In this particular issue, the Constitutional Court (2008) held,

From the content of these [constitutional] provisions, it could be concluded that the Constituent sponsored the idea of making the economic development compatible with the right to a healthy environment and an ecological balance.

Hence, the content of the constitutional principle to protect the environment must be harmonized with the idea of "sustainable development", but ensuring in any case the conservation, preservation and protection of the environment and natural sources under rational and proportional parameters.

The constitutional right to enjoy a healthy environment

According to article 79 of the Constitution, "Every person has the right to enjoy a healthy environment". This right is classified by the Constitution as a "collective" right and has been defined by the Constitutional Court as the basic conditions surrounding individuals, which allow their biological survival and guarantee their normal performance and balanced development within society (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1997a). In this sense, the Court has classified the right to a healthy environment as essential for the survival of our species.

As a collective right, this right to a healthy environment holds as its main characteristic that its title transcends the individual and, in consequence, the concept of subjective right, to settle in the human as a social being. Thus, the protection of the right does not lie only on the duty of the State, but also, as will be presented later, of other social entities like, citizens, corporations and the international community itself. Also, collective rights arise from human activities and needs, as varied as the development of science and technology, exploitation of resources in a sustained population growth scenario, and wars or armed conflicts. Since these activities are ongoing and unpredictable, the scope and protection of collective rights are also characterized by a dynamic development as a strategy to respond to the future needs in this regard. Another characteristic of the collective rights is the preventive orientation that they imply to anticipate any future violation attending to the relevance of the content of the right.

For the protection of the right to enjoy a healthy environment, the Constitution provided for all collective rights a constitutional action called "popular actions" [acciones populares]. Despite the fact that this constitutional action was provided on Article 88 of the Constitution, for its implementation it was required that Congress developed this action to be implemented. Therefore, in absence of the law about this matter, in principle, the right to environment and the other collective rights did not have a protection mechanism. However, until the enactment of the law developing "popular action", the Constitutional Court held the position that, attending to the relevance of the right to a healthy environment, this right acquires in some cases, and by "connection", the status of "fundamental right", due to its inherent relation with the right to life (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2000). In consequence, during this time, the Court admitted the possibility to protect the right to a healthy environment through the constitutional writ of protection of fundamental rights [accion de tutela]1.

Consequently, the Constitutional Court has issued some tutela decisions protecting the right to a healthy environment when there have been specific actions of environmental disruption or degradation, and when the integrity of this right is threatened. For example, in a 1997 tu-tela decision, the Court protected the rights of private citizens affected by a smell caused by their neighbor's septic tank, which had not received the appropriate attention of relevant authorities. Stating that the neighbor's undue disruption of the plaintiff's domestic environment constituted a threat to their rights to health, life and healthy environment, the Court ordered the removal of the tank and the installation of adequate drainage facilities (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1997b)

Also, in a 1999 decision, the Court reviewed the tutela presented by a woman on behalf of herself, her family and her neighbors. These citizens lived in poor households alongside a seriously faulty municipal landfill, which had noxious effects on their daily environments and their health. The Court granted the tutela, because it considered the disruption of the right to a healthy environment to be a severe threat to the fundamental rights to health and life. Consequently, the Court ordered municipal authorities to buy the plaintiff's land next to the landfill, so she could purchase adequate living elsewhere. In the alternative, the Court ordered the authorities to suspend use of the landfill (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1999).

With the enactment of the Law Number 472 of 1998, Congress finally regulated "popular action". According to this law, collective rights and interests, including the enjoyment of a healthy environment, can be protected by this action. This is a judicial action, regulated by an expedited procedure and proceeds before public and private institutions or individuals. The nature of this action is prevalently preventive and reparative because in principle this action does not allow plaintiffs to seek damages or monetary compensation.

Regarding the applicability of "popular action" in environmental matters, for some authors it is by far the most common mechanism for the protection of environmental rights. Although "popular action" does not allow plaintiffs to seek damages, it does aim to prevent environmental damages and requires the offender to adopt the necessary measures to restore things to their former state (Rincon-Rubiano, 2001). When the violation to collective rights involves deterioration of natural resources, the Judge is enabled to fix a compensatory amount to restore the affected area. "Popular actions", thus, can be used to prevent and repair environmental damage affecting collective rights of the community.

Hence, the right to enjoy a healthy environment is a constitutional collective right, whose entitlement belongs to all Colombian citizens. As a collective right, it protection, in principle, must be through the mechanism of "popular action". This is a particular judicial action with a preventive or protective nature. Exceptionally, the right to enjoy a healthy environment has been considered as a fundamental right by the Constitutional Court, due to its connection with other rights like life or health. In those exceptional cases, the right to environment can be protected by tutela.

The Constitutional Correlative Duties to Protect the Environment

As was said before, the collective nature of the right to enjoy a healthy environment implies correlative duties by the Constitution. Those duties of protection and conservation of the environment lie not only on the State, but also on citizens, corporations and other social entities.

About the duties of the State regarding the protection of the environment, the Constitution enlists the following: (i) protecting the diversity and integrity (Article 7 C. P.); (ii) safeguarding the natural wealth of the nation (Article 8 C. P.); (iii) preserving areas of special ecological importance (Article 79 C. P.); (iv) promoting environmental education (Article 67 C. P.); (v) planning the management and utilization of natural resources and ensure their sustainable development, conservation, restoration or replacement (Article 80 C. P.); (vi) preventing and controlling environmental deterioration factors (Article 80 C. P.); (vii) imposing legal sanctions and demanding reparation for the damage caused to the environment (Article 80 C. P.); and (viii) cooperating with other nations in the protection of ecosystems in the border areas (Article 80 C. P.).

About the duties of private people, the Constitution expressly provides on Article 95.8 of the Constitution as a duty for each person and citizen: "To protect the country's cultural and natural resources and watch over the conservation of a healthy environment". To interpret this disposition, it is relevant to consider what was presented above about the constitutional principle of protection of the environment and what the scope of the term conservation is in this context. This duty to protect the environment, both by the State and private actors, is a clear consequence of the collective nature of this right and, therefore, this is why the "popular action" proceeds against the State or private actors. About this issue, the Constitutional Court (2007b) has said:

Plainly, in these [constitutional] provisions are stated an attribution to each person to enjoy a healthy environment, a State obligation and for all Colombians to protect the diversity e integrity of the environment, and a faculty by the State to prevent and control the factors of depletion and guarantee it sustainable development, conservation, restoration and substitution.

Also, in concrete cases the Constitutional Court has referred to the scope of the duties derived of the right to a healthy environment. In 1997, the Court admitted a tutela action about the situation of environmental degradation in the coastal city of Santa Marta. In this decision the Court examined a complaint filed by several inhabitants against local authorities, which argued that the generalized pollution of the sea and beaches, and the inadequacy of urban drainage systems, were due to the city's lack of planning and control over sewage disposal, urban construction, and coal shipping (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2007a). The Court granted the tutela to protect the plaintiffs' rights to a healthy environment, life and health. The Court felt these rights were violated by the local authorities' failure to regulate land use and urban growth, and excessive issuing of construction licenses. As a consequence, the Court ordered the pertinent public entities to issue a plan for the regulation of land use in the District of Santa Marta, which was to include sewage disposal systems in accordance with legal requirements. The Court also ordered that construction licenses should be granted by the relevant environmental authorities and prohibited license conferral in certain particularly degraded areas of the city. As to the noxious effects of air pollution caused by coal shipping activities, the Court ordered the Ministry of the Environment to adopt a comprehensive plan for the management of coal, through its extraction and commercialization processes, in order to avoid negative impacts on human health.

THE PROCESSES OF "INTERNATIONALIZATION" AND "CONSTITUTIONALIZATION" OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN COLOMBIA

International law and the "Constitutional block" in Colombia

The binding sources of international environmental law are treaties, international customary and general principles of international law. As a general rule under the idea of State sovereignty, each State must consent to limit their sovereignty and bind themselves to the terms of a treaty, or consent to recognize a principle of customary law or of general international law. Therefore, in principle, each of these sources requires a process of "domestication" whereby international obligations are incorporated into the national legal system (Hunter, Salzman & Zaelke, 2006).

Colombian Constitution provided a process for the approval of international treaties. In the first place, the Constitution recognizes to the executive branch, represented by the President of the Republic, the power to manage international relations. As part of this power, the President, directly, through his or her Minister of Foreign Affairs or delegated, can negotiate and celebrate international treaties and agreements with other states and/or international bodies. These treaties, once negotiated and celebrated must be submitted for the approval of Congress. Therefore, Congress has the constitutional power to approve or disapprove treaties, which the government makes with other states or international organizations. To approve a treaty, Congress should enact a bill establishing explicitly the approval of the treaty, following the requisites for an ordinary law, and start its discussion in the Senate. After the enactment of the law and its content, the President must decide whether to sanction the bill or not. In the case that the President decides to sanction it, he or she must submit the law before the Constitutional Court for its revision.

The Constitutional Court has the power to decide in definitive manner on the constitutionality of the laws approving international treaties. Doing so, the Court makes a judicial review in which it analyzes the fulfillment of the formal requisites in the creation of the law, but also, the material compatibility between the content of the treaty and the Constitution. Only in the case in which the Court declares the constitutionality of the treaty, the government can continue with the ratification of the treaty.

From this process, it could be concluded that, in principle, the international treaties ratified by Colombia have the same legal hierarchy of an ordinary statutory law. In this sense, the Constitutional Court has arrived to the same statement establishing that "International treaties, by the mere fact of being, do not have a superior hierarchy than the ordinary laws" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1998). This conclusion supposes two relevant consequences: (i) the content of international treaties do not constitute constitutional parameters for the other provisions of the legal system; and (ii) a statute could not be in principle declared as unconstitutional because of being contrary to the content of an international treaty ratified by Colombia.

However, this general rule has an exception. Attending to the content of some constitutional provisions, called "forward clauses", the Constitutional Court has developed the doctrine of the "Constitutional Block", similarly to the French constitutional model. For the Court, the "Constitutional Block" is composed of a set of rules, norms and principles that, without formally appearing in the text of the Constitution, are used as control parameters of the constitutionality of statutes because they have been normatively integrated into the Constitution, in various ways by the mandate of the Constitution itself. They are truly principles and rules of constitutional value and hierarchy. In other words, they are norms located at the same constitutional level, although it may contain different mechanisms of reform from the constitutional norms in strict sense. In this point, the Constitutional Court (2003) has said:

The fact that the regulations included in the constitutional block have constitutional status makes them true sources of law, which means that judges in their rulings and legal subjects in their official or private behavior should stick to their prescriptions. As the preamble, principles, values and constitutional rules are mandatory and binding upon the internal order, the rules of the constitutional block are source of law binding on all citizens. ... The sharing of the hierarchy of the formal text of the Constitution makes the "axis and factor of unity and cohesion of society" out of the Block's norms, and requires that all domestic legislation condition their content and adjust their precepts to those adopted statutes, since they radiate their power over the whole legal system.

Hence, the Constitutional provisions and the rules that make part of the Block are normatively equal and do not have any legal difference. In this sense, both sets of provisions will share the constitutional functions, inter alia: (i) to irradiate the legal system, making that any action of the State or any normative disposition must respect this norms, inasmuch as possible, and in accordance with the other constitutional rules, principles and values; (ii) to serve as a constitutional parameter to evaluate the constitutionality of provisions of lower hierarchy; (iii) to serve as a interpretative parameter for other constitutional or even lower hierarchy norms; and (iv) to serve as integrative criteria in absence of expressly constitution rules in this regard. Also, for a practical sense, any legal norm could be demanded as unconstitutional if the content of this statute does not conform with the content of the Constitutional law, including the provisions that belong to the Constitutional Block.

A clear example of a set of rules that belongs to the "Constitutional Block" is the International Humanitarian Law. In virtue of the "forward clause" contained in Article 93 of the Constitution, which establishes: "International treaties and agreements ratified by the Congress that recognize human rights and that prohibit their limitation in states of emergency have priority domestically", the Court has held that it is clear that international humanitarian law treaties fulfill the requisites of Article 93 because they recognize human rights and cannot be limited even during armed conflicts or states of emergency, therefore, they make part of the "Constitutional Block" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2001).

The "internationalization" of the environmental law in Colombia

The protection of the environment by the international law has been intensified simultaneously with the development of the domestic legislation in most countries, as a response to the growing depletion of the environment and the threats of its evident degradation in the future. It is well known that the greater causes of impact to the environment are anthropogenic, i.e. those derived from human activity aimed at meeting their needs. These activities began to be developed especially since the XIX century when industrial processes and world population increased abruptly. These activities where exercised without any sustainability criteria, generating a negative impact on natural resources and the global ecosystem. Today, these environmental impacts are obvious: pollution by land, air and sea, acid rain, depletion of the ozone layer, global warming, extinction of wildlife species, habitat degradation, and deforestation, among many others (Hunter, Salzman & Zaelke, 2006).

In opposition to the principle of state sovereignty that implies the self-determination and the subsequent defense of interests framed within the limits of political boundaries, the environmental degradation transcends these boundaries and has become a global problem. Consequently, its protection becomes a purpose of all states, which in turn are united for a common future. In general, different ecosystems are multidimensional and the elements of each bear a complex inter- relationship. Therefore, they do not contemplate geopolitical boundaries2. Only few countries still consider environmental policy as a strictly internal matter. Every day it is more obvious that the protection of the environment requires international regulation to consolidate bilateral and multilateral instruments to address that common purpose effectively, not only legally, but socially, politically and economically.

The Constituent Assembly of 1991 was aware of this situation and, in the Constitution, it recognized the necessity for international instruments to regulate the management of shared natural resources and the preservation of the environmental degradation internationally. The Constitution, in Article 226 notes that: "The state will promote the internationalization of political, economic, social and ecological relations on the basis of fairness, reciprocity, and the national interest" (Colombian Constitution, 1991). In consequence, the Colombian State has the duty to promote the ecological international relations through international environmental law and policies.

This reasoning has also been adopted by the Constitutional jurisprudence. The Constitutional Court has recognized that the environmental law is an issue that escapes the frontiers of any country and required international commitment. This commitment imposes on the State the duty to promote and to adopt cooperative measures among other countries that could later become in international binding instruments for the protection and conservation of the global environment. In this sense, the Court (1995) held:

... The factors that lead to environmental degradation cannot be considered in its effect, as a problem that is relevant only to a particular country, but the problem concerns all countries, since environmental preservation is an interest of all humanity, without distinction of borders. Therefore, our State imposes the duty to take measures to cooperate with other countries, as provided for in Article 226 of the Constitution, to prevent harmful actions of different agents that could damage the environment, as in the case of ozone, because such actions are occurring in all countries and if unchecked, can seriously affect the conditions and quality of life of all inhabitants of the planet.

Hence, from the content of Article 226 of the Constitution, the Constitutional Court has said that internationalization is one of the distinctive features of the ecological relations. This tendency is evident in the increasing number of ratifications that Colombia has made of international instruments aimed to preserve a healthy environment. Therefore, the Constitutional Court has upheld as constitutional all the international environmental instruments approved by Congress and has considered them as a materialization of the mandate contained in Article 226 of the Constitution. Some of these instruments are, the Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2000), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1995), the Kyoto Protocol of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2001), the United Nations Convention to Fight Desertification (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1999), the Ramsar Convention for the protection of Wetlands (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1997), and the Convention on Biodiversity (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1994), among others.

The "constitutionalization" of the international environmental law in Colombia

From what was presented above, it could be hold that according to the mandate contained on Article 226 of the Constitution the State has the duty to promote the international environmental cooperation. The necessity of this mandate has been also recognized in the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court, which has considered that the approval of an international environmental treaty is the materialization of this mandate. However, from this reasoning the legal hierarchy of the international environmental treaties ratified by Colombia technically has not been changed, and as was said before, the legal hierarchy of these norms will be the same as an ordinary statutory law in the Colombian legal system.

But the conclusion of this reasoning has been changing in recent decisions by the Constitutional Court. Since a seminal ruling of the Court in 2003, and reiterated on further decisions, the scope and implications of the mandate contained on Article 226 seems to have changed. In these cases, the Court considered that this mandate not only contained the duty of the State to promote international environmental cooperation but also that some international rules, due to its direct relation with other constitutional provisions, may acquire the legal hierarchy of Constitutional principles and become in constitutional parameters. In other words, that the Article 226 of the Constitution implies a "forward clause", similar to the one contained on Article 93, that makes that some international norms become part of the "Constitutional Block", and therefore, shall be considered as constitutional-based-norms in a legal sense.

Despite that the Court did not refer to the doctrine of the "Constitutional Block" in these rulings, the Court use the term "constitutionalized", meaning that an international environmental rule had been adopted as part of the Constitution. But this is not the only opportunity in which the Court has used this term about an international environmental principle. In other rulings, the Court not only has affirmed that an international environmental provision has been "constitutionalized", but also has used it as a constitutional parameter in judicial review cases. Thus, from the developments that the Court has made until today, this new normative phenomenon could be called as the judicial "constitutionalization" of the international environmental law3.

Nevertheless, this is a relatively new position that the Court has not yet elaborated deeply on the reasons and implications on this decision, from a constitutional and environmental law perspective, its effects and implications are quite relevant. First, because at least some principles of the international environmental law will become Constitutional provisions, thus they will be constitutional parameters in all its effects. Second, those international environmental norms will be adopted by

the Colombian system in the highest legal hierarchy, improving its possibilities for compliance and its effectiveness, as will be presented.

THE PROCESS OF "CONSTITUTIONALIZATION" OF THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE IN THE COLOMBIAN LEGAL SYSTEM

Content and Recognition of the Precautionary Principle in the Colombian Legal System

The Precautionary Principle is a well-known principle on the international environmental law. This principle, like the principle of prevention, is concerned with taking anticipatory actions to avoid environmental harm before it occurs (Richmann, 2002). The precautionary principle, thus, provides a framework for governments to set preventative policies where existing science is incomplete or where no consensus exists regarding a particular threat (Burgos, 2009). Therefore, some authors had argued that the precautionary principle addresses how environmental decisions are made in the face of scientific uncertainty.

Despite the fact that the Colombian Constitution does not make any mention to the precautionary principle, Article 80 establishes as a duty of the State "to prevent and control the factors of environmental deterioration, impose legal sanctions, and demand the repair of any damage caused". Due to this constitutional mandate, the Colombian Government began to express it interest to assume the Precautionary Principle in the field of environmental protection signing the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. This document introduced, in its Article 15, the Precautionary Principle, under the following formula: "In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation". Although, the Rio Declaration was not created as a binding law, it reflects pretty well the political consensus around international environmental principles as of 1992 (Hunter, Salzman & Zaelke, 2006).

Just a year later, the Colombian Congress enacted the Act Number 99 of 1993 in which it created the Ministry of Environment and the National Environmental System in Colombia. In Article 1°, this bill adopted the general principles that will govern the Colombian Environmental Policy. In the first paragraph the bill states that "The process of economic and social development will be guided by universal principles of sustainable development contained in the Declaration of Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 on Environment and Development" and in paragraph six, "The formulation of environmental policies take into account the outcome of the scientific research process (Colombian National Congress, 1993). However, environmental authorities and individuals will apply the precautionary principle under which, if there are threats of serious and irreversible damage, the lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing effective measures to prevent degradation environment.

In 1994, a citizen claimed the unconstitutionality of the entire article 1° of the Act 99 because, in his concept, this provision implied an irregular and hidden incorporation of an international treaty without the constitutional requirements to do so. The Court, in ruling C-528 of 1994, denied the claim and declared the constitutionality of the article. In this decision, the Court evidenced that the Rio Declaration is not an international treaty or document subject to ratification by the States or International Organizations because, formally, it is just a declaration made by The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Therefore, the remission made by the legislator to subscribe to the content of the Rio Declaration, and incorporated it to the Colombian legal system, was an autonomous and Constitutional decision that did not require any other formal condition. About the legal hierarchy of these principles in the legal system the Court (1996a) held,

In this case the principles to which the provision [article 1 of the Act 99 of 1993] refers are not constitutional, general or fundamental to the legal and political system, as might be initially understood and as the plaintiff wants to understand it, saying that they are equal to the preamble of the Constitution. These principles did not serve as a condition for the entire organization of the State, nor to irradiate the entire legal system but they operate with the ability to be guiding the conduct of officials in charge of advancing the fulfillment of the remaining parts of the law.

Hence, in this decision the Court was clear saying that despite these principles have legal force by the decision of the Congress, they are not constitutional based principles, only statutory-based-principles that apply to others statutory or lower norms in the Colombia's legal system. In other words, those principles do not belong to the "Constitutional Block" and do not have any constitutional function, according to the decision made by the Colombian Congress.

Then, in a 1996 tutela case, the Court had the opportunity to refer and apply the Precautionary Principle. In this case the Court assessed the impact of a serious oil pollution incident in the Pacific Ocean upon the members of an Afro-Colombian coastal community who depended on fishing for their livelihood. Taking into account that the affected community was entitled to special constitutional protection as an ethnic group, the Court restated the State's special obligations for environmental preservation. This judgment is important in this point because it stressed the importance of the Precautionary Principle for Colombian authorities and expressly said,

When potential damage to the environment has a significant uncertainty and it is necessary to act on the basis of the precautionary principle, that is, it should be used to address all potential environmental damage, both of the responsibility of the government and the private" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 1996b).

But about the legal status of the Precautionary Principle, the Court stated that precaution is a statutory function of the Minister of Environment in virtue of the Act 99 of 1993. The same holding was reiterated later by the Court on ruling C- 293 of 2002 (Arcila, 2009).

The Precautionary Principle as a Constitutional parameter in the Colombian Legal System

In the same year, the Court used for the first time the Precautionary Principle as a constitutional parameter. In this case, the Court revised the constitutionality of some norms of the Mining Code. One of the norms analyzed referred to the faculty of the State to exclude some zones for the mining activity due to its relevance to the protection of the environment. The Court upheld the constitutionality of this norm based in the Precautionary Principle and despite it did not make further elaboration about the legal hierarchy of this principle; it made a direct use of the principle in the reasoning. In this regard, the Court held,

In the event of a lack of scientific certainty or against mining exploration in a given area, the decision must necessarily lean towards protecting the environment because if we conducted the mining activity and then demonstrated that it caused severe environmental damage, it would be impossible to reverse its consequences. (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2002)

The "Constitutionalization" of the Precautionary Principle

Two years later, the Court in the ruling C-988 of 2004 recognized explicitly for the first time that the Precautionary Principle made part of the Colombian Constitution. In this case, the Court took up the study of the constitutionality of a provision that allows the State to deny the registration of generic agrochemicals potentially harmful to the environment and public health, when sharing an agrochemical active ingredient already registered and approved by the environmental authorities. To decide the case, the Court held, "The Constitution has constitutionalized the "Precautionary Principle" because the Constitution imposed to the authorities the duty to prevent damage and risk to life, health and the environment" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2004). Thus, the Court based on this principle declared the constitutionality of the legislative measure.

This position has been reiterated on two further cases. In the tutela case T-299 of 2008, the Court held,

According to a recent ruling of this Corporation [Decision C-988 of 2004], the Precautionary Principle is constitutionalized because it emerges from the internationalization of the ecological relations (art. 266 CP) and from the duties of protection and prevention contained in articles 80 of the Charter" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2008).

Then, in ruling C-595 of 2010 and after transcribing the previous quote from the ruling T-299 of 2008, the Court states, "The Precautionary Principle is a constitutional and international tool of great relevance to determine the necessity of intervention of the public authorities before the potential risks to the environment and to public health" (Colombian Constitutional Court, 2010). In both cases, the Court used the Precautionary Principle as a constitutional parameter (Agudelo, 2011).

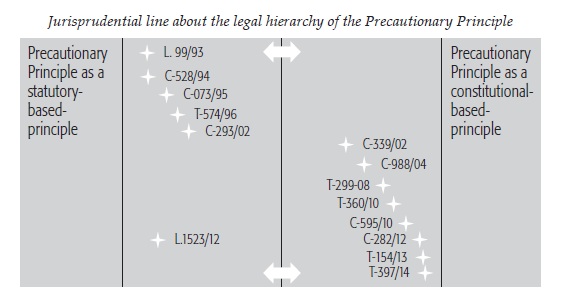

The same holding, even quoting the mentioned decisions in the dictum, has been settled peacefully by the Constitutional Court until today. The following chart shows the evolution of the jurisprudence and the most recent rulings about that particular issue.

Summarizing, in regards to the scope of the Precautionary Principle in the Colombian legal system, it could be stated (i) the Colombian State was interested in applying the precautionary principle when it signed the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development; (ii) the principle is part of the positive law with a statutory-based hierarchy since the enactment of Act 99 of 1993 in which Colombia adopted the principles of the Rio Declaration; (iii) the enactment of this bill was not unconstitutional, by contrast, it is consistent with the principles of self-determination of peoples, and the duties of the State relating to the protection of the environment; (iv) according to recent holdings made by the Colombian Constitutional Court, the precautionary principle has been "constitutionalized" in virtue of the constitutional mandate on internationalization of ecological relationships (art. 266 of the Constitution) and the constitutional duties of prevention and protection contained in Article 80 of the Constitution. Therefore, currently and according to the constitutional jurisprudence, the Precautionary Principle is not only a statutory- principle, but also a constitutional-based-principle in the Colombian legal hierarchy.

CONCLUSIONS

The Colombian Constitution has a great interest in the environment issues. This becomes evident in the fact that at least 45 of its norms made any reference to the protection of the environment. Thus, the Constitutional Court has considered it as an "Ecological Constitution". The content of the Constitution takes different approaches to the environment protection. First, an ethical approach based on the symbiosis of human species and environment; second, an economic perspective focused in the idea of "sustainable development"; and third, a legal approach.

This legal perspective is developed on the Constitution by three different institutions. Firstly, the Constitution establishes a constitutional-based principle for the environmental protection, which must irradiate the content and interpretation of all the legal system. Secondly, the Constitution provides a constitutional collective right to enjoy a healthy environment, which must be protected by the mechanism of "popular action", and exceptionally by tutela. Thirdly, the Constitution provides some correlative duties for the State, citizens and private entities to address the protection of the environment.

This Constitutional framework also includes the possibility to introduce international environmental norms to the legal system. As a general rule, the Constitution provides a process of ratification for international norms to make them part of Colombian legal system. This process requires the interaction of the three branches of power and allows that an international norm could be introduced to the Colombian legal system with the legal hierarchy of an ordinary statutory law. Exceptionally, the Constitutional Court has recognized, in virtue of some "forward clauses" included in the Constitution, that some international provisions could make part of the Constitution. This doctrine has been called as "block of constitutionality".

Being aware of the necessity to internationalize the environmental regulation, the Constitution also provides on Article 226 a mandate to the State to promote the internationalization of the environmental relations. Traditionally, the constitutional jurisprudence had interpreted that this norm provides a new duty to the State to promote international cooperation in environmental issues. However, recent rulings of the Constitutional Court have been suggesting that this norm contains a "forward clause", making that some international environmental rules that have a direct relation with the constitutional content must be considered as "constitutionalized" and, therefore, as part of the Constitution.

This was the case with the Precautionary Principle. This international principle was recognized in the Rio Declaration of 1992 and Colombian Congress decided to introduce it as a legal principle by the Law 99 of 1993 (Lora, 2011). Therefore, as the Constitutional Court recognized in 1994, this principle must serve as a guide for other statutory or lower level norms. However, in a 2002 case, the Court decided to use this principle as a parameter to analyze the constitutionality of a statutory law. Then, in a 2004 ruling, the Court held explicitly that the Precautionary Principle had been "constitutionalized" and used it again as a constitutional-based-principle. Next, in further decisions until today, the Court reiterated the "constitutionalized" nature of this principle and stated that this conclusion is based on the international mandate contained in Article 226 of the Constitution. Hence, attending to the settled position of the Court, it is possible to argue that a process of judicial "constitutionalization", at least for the precautionary principles, has been taking place in Colombia.

From a comparative perspective, it is clear that is not the first and only process of "constitutionalization" of international environmental norms. In the past, other countries, such as France, "constitutionali-zed" some international environmental norms, like in 2005 through the Charter of Environment, even the European Union, through the Treaty of Maastrich in 1993, made substantiall the same thing. However, both processes were made by political institutions (Faisini, Llie & Artene, 2012). Therefore, the mentioned process in Colombia seems to be more like the process that took place in India in 1996, in which the Supreme Court through the "Green Bench" held that some international environmental principles, like the precautionary principles, must be considered as part of the "law of the land" (Kumar-Gupta, 2012). Hence, understanding and analyzing the advantage and critics of these previous processes will be relevant for the consequences of the process that are taking place in Colombia (Arcila, 2009).

Despite that it is an ongoing process in Colombia and that the Court has not analyzed explicitly and systematically the causes and implications of this phenomenon, the only possibility that a process of this nature has been taking place is enough for the doctrine and activists to study and to analyze this new jurisprudential trend. At least, from a preliminary point of view, this new position of the Court opens new possibilities to the "constitutionalization" of other international environmental norms, and also, to the "justiciability" of these norms.

Concerning this last point, it could be quite interesting that based on the holding of the Court, the content of the precautionary principle may be invoked in actions introduced to any domestic court, not only through ordinary but also through constitutional actions. Therefore, mechanisms like strategic litigations, in which the courts play a significant role in the process of interpreting and implementing the international norms, could gain particular relevance. In doing so, it might be predictable that the level of compliance and effectiveness of the international environmental norms in Colombia could be improved. However, it is important to insist that the continuity and future of this trend will depend in the near future on the subsequent rulings of the Constitutional Court.

* This paper is the result of the academic activity of the author during the Seminar "International Environmental Law and policy" with Dr. Prof. David Hunter at Washington College of Law.

1The accion de tutela enables any person whose fundamental rights are being threatened or violated to request that a judge with territorial jurisdiction protects that person's fundamental rights. This measure serves to protect the integrity of the Constitution. Citizens may file informal claims without an attorney, before any judge in the country. That judge is legally bound to give priority attention to the request over any other business. Judges have a strict deadline of ten days to reach a decision and, where appropriate, to issue a mandatory and immediate order. About it see: Cepeda-Espinosa, M. J. (2004). Judicial Activism in a Violent Context: The Origin, Role, and Impact of the Colombian Constitutional Court, 3 Wash. U. Glob. Stud. L. Rev. 529 at 552.

2In this particular issue the Colombian Constitutional Court has said that "... The ecological factor is part of a whole, therefore, it can be argued that natural resources are of primary concern not only for the people of Colombia but for all mankind. In the care and sustainable development of nature is compromised the entire planet, under the legally protected object, as stated, is essentially universal". Colombian Constitutional Court (1994). C-423 of 1994.

3This process of "Constitutionalization" of international environmental norms is different from the process that took place in France in 2004 - 2005 because in the French process, the process was made by the Parliament, which has the explicit constitutional power to do so. In the Colombian case the "constitutionalization" is made by a judicial organ. About the process in France See: Faisini, F., Ilie, M. & Artene, D. (2012). The Insertion of the Precautionary Principle in the Environment Protection as a Legal Norm in the European Union Countries. Contemporary Readings In Law & Social Justice, 4(2), 496.

REFERENCES

Agudelo, L. E. (2011). El principio de precaucion ambiental en la sentencia C-595 de 2012 de la Corte Constitutional. Revista Verba Iuris (Bogota, D. C.: Universidad Libre de Colombia) 26. [ Links ]

Amaya, O. D. (2010). La constitucibn ecolbgica de Colombia. Bogota: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

Arcila, B. (2009). El principio de precaution y su aplicacion judicial. Revista Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Politicas (Medellin: Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana), 39 (111). [ Links ]

Banerjee, D. (2012). Environmental Jurisprudence in India: A look at the initiative of the Supreme Court of India and their success at meeting the needs of enviro-social justice. Disponible en: http://www.academia.edu/430162/Environmental_ju-risprudence_in_India_A_look_at_the_initiatives_of_the_Supreme_Court_ of_India_and_their_success_at_meeting_the_needs_of_enviro-social_jus-tice. [ Links ]

Burgos, M. S. (2009). Algunas reflexiones sobre el principio de precaucion y su fuerza vinculante. Lecturas sobre derecho del Medio Ambiente, t. Bogota, D. C.: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

Cepeda-Espinosa, M.J. (2004). Judicial Activism in a Violent Context: The Origin, Role, and Impact of the Colombian Constitutional Court. 3 Wash. U. Glob. Stud. L. Rev, 529. [ Links ]

Faisini, F., Ilie, M. & Artene, D. (2012). The Insertion of the Precautionary Principle in the Environment Protection as a Legal Norm in the European Union Countries. Contemporary Readings in Law & Social Justice (Boston: Boston College), 4(2) 496. [ Links ]

Garcia, L. (2002). Teoria del desarrollo sostenible y legislacion ambiental co-lombiana, una reflexion cultural. Revista de Derecho (Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte), 20. [ Links ]

Hunter, D. Salzman, J. & Zaelke, D. (2006). International Environmental Law and Policy. New York: Foundation Press. [ Links ]

Jobodwana, Z. (2011). Integrating International Environmental Principles and norms into the South African Legal System and Policies. US-China Law Review (California: David Publishing Company), 8(8). [ Links ]

Kumar-Gupta, S. (2012). Principles of International Environmental Law and Judicial Response in India. Available at: http://www.google.com/url?sa= t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CCwQFjAA&u rl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bhu.ac.in%2Flawfaculty%2Fblj2006-072008-09%2FBLJ_2007%2F11_Dr.%2520S.K.%2520Gupta%2520-Artical%2520 on%2520Int%27l%2520Envt%27l%2520_Law_Corrected_on.doc&ei=v-yFUbaNLOj_4AOOxICACw&usg=AFQjCNGBb5bQdhxtgSE1-4dyJ4uPiDnqkA&bvm=bv.45960087,d.dmg. (last accessed May 1, 2014). [ Links ]

Lora, K. I. (2011). El principio de precaution en la legislation ambiental co-lombiana. Revista Actualidad Juridica (Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte), 3-4. [ Links ]

Marsden, S. (2011). Invoking Direct Application and Effect of International Treaties by the European Court Of Justice: Implications for International Environmental Law in the European Union. International & Comparative Law Quarterly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 60(3). [ Links ]

Rincon-Rubiano, D. (2001). Environmental Law in Colombia. London: Wolters Kluwer. [ Links ]

Riechmann, J. (2002). Un principio para reorientar las relaciones de la huma-nidad con la Biosfera. En J. Riechmann & J. Tickner. (comp.), El Principio de Precaucibn en medio ambiente y salud publica: de las definiciones a la prdctica (pp. 7-37). Barcelona: Icaria. [ Links ]

The World Commission on Environment and Development's (the Brindtland Commission) (1987). Report: Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

United Nations (1992). Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992. A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I). [ Links ]

Sentencias de la Corte Constitucional [Colombian Constitutional Court] [ Links ].

Sentencia T-254 de 1993. Sentencia C-519 de 1994. Sentencia C-418 de 1994. [ Links ]

Sentencia C-073de 1995(a). Sentencia C-418 de 1995(b). Sentencia T-594 de 1996. [ Links ]

Sentencia T-071 de 1997(a). [ Links ]

Sentencia SU-442 de 1997(b). [ Links ]

Sentencia C-582 de 1997(c). Sentencia C-126 de 1998(a). Sentencia C-191 de 1998(b). Sentencia T-046 de 1999(a). Sentencia C-229 de 1999(b). Sentencia C- 431 de 2000(a). [ Links ]

Sentencia C-1314 de 2000(b). [ Links ]

Sentencia C-177 de 2001(a). Sentencia C-860 de 2001(b). Sentencia C-339 de 2002(a). Sentencia C-377 de 2002(b). Sentencia C-067 de 2003. Sentencia C-988 de 2004. Sentencia SU-442 de 2007(a). Sentencia T-760 de 2007(b). Sentencia T-299 de 2008(a). Sentencia C-750 de 2008(b). Sentencia C-595 de 2010. [ Links ]