Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista MVZ Córdoba

Print version ISSN 0122-0268

Rev.MVZ Cordoba vol.19 no.1 Córdoba Jan./Apr. 2014

ORIGINAL

Some ecological aspects of free-living Haemaphysalis juxtakochi Cooley, 1946 (Acari: Ixodidae) in Panama

Algunos aspectos ecológicos de fases de vida libre de Haemaphysalis juxtakochi Cooley, 1946 (Acari: Ixodidae) en Panamá

Gleydis García G,1 Lic, Angélica Castro DF,1 Lic, Sergio Bermúdez C,1* M.Sc, Santiago Nava,2 Ph.D.

1Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá 0816-02593.

2Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Rafaela y Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, CC 22, CP 2300 Rafaela, Santa Fe, Argentina.

*Correspondence: bermudezsec@gmail.com

Received: February 2013; Accepted: November 2013.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To describe the seasonal variation and perform a comparative analysis on habitat preference of Haemaphysalis juxtakochi in Panama. Materials and methods. Ticks were collected from the vegetation, using a white cloth, between January 2009 and March 2010, in four site located in Summit Municipal Park (SMP), two in wooded area (WA) and two in grasslands (GR).The ticks were determined as larvae, nymphs and adults of H. juxtakochi. The number of ticks collected in each area was employed to describe the seasonal distribution of both immature and adult stages, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Results. A total of 2.338 ticks in WA and 560 ticks in GR were collected. The major peak of adults from May to July, nymphs peaked from January to April and the peak of larvae abundance from December and January. There was a significant difference in the number of ticks collected in the two areas for each tick stage (larvae, mean number (MN) in WA 120.14, MN in GR 57.07, P: 0.02; nymphs, MN in WA 46.42, MN in GR 16.38, P: 0.018; adults, MN in WA 6.64, MN in GR 1.78, P: 0.02). Conclusions. The results suggest that H. juxtakochi maintains a one-year cycle in the study areas. This cycle would be characterized by the immature population peaks in the dry season; while adults are distributed throughout year, with a peak in the transition from the rainy and dry. Moreover, H. juxtakochi was more abundant in forests than in grasslands, which could lead to a better adaptation to forested conditions.

Key words: Abundance, distribution, environment, host, stages, ticks (Source: DeCYT).

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Describir la variación estacional y realizar un análisis comparativo de la preferencia de hábitat de H. juxtakochi en Panamá. Materiales y métodos. Se recolectaron mensualmente garrapatas de la vegetación utilizando una tela blanca, entre enero de 2009 y marzo de 2010 en cuatro sitios establecidos en el Parque Municipal Summit (PMS), dos en área de pastizales (AP) y dos en área boscosa (AB). Las garrapatas fueron identificadas como larva, ninfa y adulto de H. juxtakochi. El número de garrapatas recolectadas en cada área fue empleado para describir la distribución estacional de ambos estadios inmaduros y adultos, y se compararon con la prueba no paramétrica Mann-Whitney U. Resultados. Se recolectó un total de 2.338 garrapatas en AP y 560 garrapatas en AB. El mayor pico de garrapatas adultas fue de mayo hasta julio, los picos de ninfas fueron de enero hasta abril y los picos de abundancia de larvas desde diciembre hasta enero. Hubo diferencias significativas en el número de garrapatas recolectadas en las dos áreas para cada estadio (número promedio de larvas en AB 120.14, en AP 57.07, P: 0.02; número promedio de ninfas en AB 46.42, en AP 16.38, P:0.018; número promedio de adultos en AB 6.64, en AP 1.78, P: 0.02). Conclusiones. Los resultados sugieren que H. juxtakochi mantiene un ciclo de un año en las áreas de estudio. Este ciclo estaría caracterizado por picos poblacionales de ejemplares inmaduros en la época seca; mientras que los adultos se distribuyen a lo largo de todo año, con un pico en la transición entre la época lluviosa y seca. Por otra parte, H. juxtakochi fue más abundante en bosques que en pastizales, lo cual podría suponer mejores adaptaciones a condiciones boscosas.

Palabras clave: Abundancia, ambiente, distribución, estadio, garrapatas, huésped (Fuente: DeCS).INTRODUCTION

The spatial and temporal risk of tick-borne disease is closely associated with the distribution, abundance and seasonal dynamics of the vector ticks (1). Therefore, knowledge of ecology of ticks is essential to make epidemiological inferences about the risk of tick-borne diseases in a particular region. Information on ecology of ticks in Panama is scarce. Although studies about host-association and distribution of ticks were carried out in this country (2-7), there are not characterizations of ecological aspects as seasonal distribution and habitat preference of Panamanian ticks. Fairchild et al (3), present some generalizations concerning environmental limiting factors for tick distribution in Panama, but without an analytical scrutiny.

One of the ticks with widely distributed in Panama is Haemaphysalis juxtakochi (8). This species was recorded in several localities from Panama, Colón, Chiriquí Provinces, even in Coiba Island National Park (4-6,8,9). The host recorded for H. juxtakochi in Panama were Tapirus bairdii (male and female), Odocoileus virginianus (male, female, nymph and larva), Coendou rothschildi (nymph), Nasua nasua (nymph) and "peccary" (nymph) (4,9). The records with sanitary relevance correspond to domestic mammals as dogs, goats, even humans (5,6).

There is not information about the ecology of H. juxtakochi not only in Panama, but neither also in the Neotropics, in spite of its wide distribution in this Biogeographic region (10). Therefore, the aim of this work was to describe the seasonal variation and perform a comparative analysis on habitat preference of H. juxtakochi in Panama.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area. The study was conducted in Summit Municipal Park (SMP), which is located on the eastern edge of the Panama Canal, 15 miles from Panama City (9°3'59.91" N, 79°38'45.98" W). The climate is tropical wet as classified by Holdridge (11), and the average temperature is 27°C; whereby the physiognomy which characterizes the SMP is given by the tropical rainforest, cleared patches that have been populated with Saccharum spontaneum, and introduced herbaceous and mixed plains. SMP is surrounded by Soberania National Park, which has an approximate area of ââ1945 hectares of primary and secondary rain forest and has a high diversity, including 105 species of mammals, 525 of birds, 134 of reptiles and amphibians (4).

Ticks collecting. Ticks were monthly collected from vegetation between January 2009 and March 2010, using cloth flags (45 x 45 cm) and looking individuals on the undersides of leaves. All ticks were preserved in 96% ethanol. Four sites were selected for sampling, two in wooded area (WA) and two in grasslands (GR), where grids of 100 m2 were established to carry out the sampling of ticks. Each site was sampled to 0800-1000 hours. Because in Panama only be established with certainty the identification of the three stages of H. juxtakochi, the study was emphasized in this species. The ticks were determined following Cooley (8) and Kohls (9).

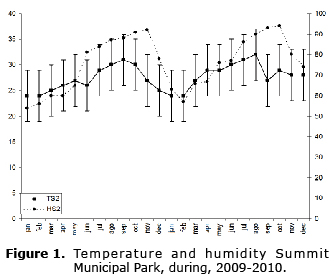

Statistical analyses. The number of ticks collected in each area was employed to describe the seasonal distribution of both immature and adult stages, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test with a level of significance of 0.05 was used to compare number of ticks between WA and GR. Temperature and relative humidity were measured monthly in each site (Figure 1).

RESULTS

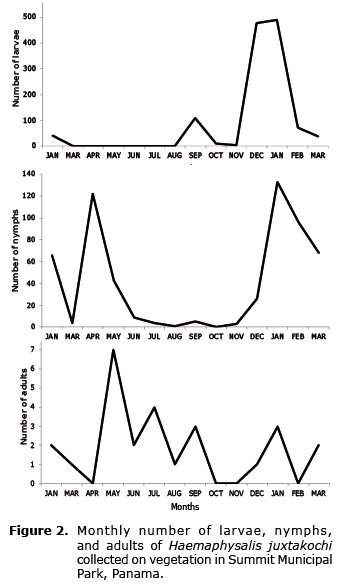

Immature and adults of H. juxtakochi were collected in both areas, 2338 ticks in WA (1278 larvae, 984 nymphs, 76 adults) and 560 ticks in GR (342 larvae, 195 nymphs, 23 adults). The seasonal variation (expressed as the number of specimens collected in each month, and considering ticks from WA and GR together) in the number of larvae, nymphs and adults of this tick species is presented in figure 2. Although there is a major peak of adults from May to July, they were found during the whole year. Contrarily, larvae and nymphs showed a more pronounced seasonal pattern. Larvae were collected from September to March, with the peak of abundance in December and January, while nymphs peaked from January to April.

Although all stages of H. juxtakochi were found in both WA and GR, there was a significant difference in the number of ticks collected in the two areas for each tick stage (larvae, mean number (MN) in WA 120.14, MN in GR 57.07, P: 0.02; nymphs, MN in WA 46.42, MN in GR 16.38, P: 0.018; adults, MN in WA 6.64, MN in GR 1.78, P: 0.02).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that H. juxtakochi has a one-year life cycle, at least in the studies areas. Larvae which were active from September to March emerged into the nymphs present in the environment from January to April, and these nymphs develop into the adult ticks that reach the peak of abundance from May to July.

Because adults were found during the whole year, it is probable that the environmental conditions in the study area are suitable for a long survival of these stages. Thus, the period in that adults are found in the environment is probably related to the recruitment rates associated to host density. In the case of the immature, small mammals and birds are parasitized for immature (Bermúdez unpublished data). So far, in SMP it is no known as populations of mammals or birds vary throughout the seasons, knowing only the increase in the number of birds during the migration season (aprox. November-April), (12).

Two hypotheses can be sketched out to explain these results. One of this is related to host usage, because tick dispersion depends of host mobility. Haemaphysalis juxtakochi is a tick species with a wide range of hosts and there are records of adults parasitizing large and medium size mammal species belonging to different families such as Cervidae, Bovidae, Camelidae, Equidae, Tapiridae, Tayassuidae, Leporidae and Dasypodidae (13). The immature stages also appear to be catholic feeders, because they were found associated to different species of mammals (families Cervidae, Tayassuidae, Procyonidae, Sciuridae, besides Felidae, Canidae, Leporidae, Dasyproctidae, and Erethizontidae) and birds (families Turdidae, Emberizidae, Corvidae, Falconidae) (13). In Panama, the principal hosts of H. juxtakochi adults are Artiodactyla, especially white-tailed deer and peccaries (Bermúdez unpublished data), and of these, the white-tailed deer appear to be very common in west bank of the Panama Canal, wandering through forest and grass areas (14).

Thus, this capacity of H. juxtakochi to feed on hosts with different ecological preferences and, in several cases, a considerable vigility, allows rejecting the hypothesis that host usage determines a major number of ticks in WA. A second and more plausible hypothesis is based in the differences in microclimatic conditions between WA and GR (12). It is probable that microclimatic conditions in WA are better than those of GR to the development of the non-parasitic phase (moulting of engorged larvae and nymphs, oviposition of engorged females, incubation of eggs, host-seeking). This hypothesis agrees with the general idea of Ixodidae ticks are more habitat-specific than host-specific (12); however, further experimental studies on nonparasitic phase of H. juxtakochi should be designed to test this second hypothesis, besides complement with more data about parasitic phases.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially sponsored by Secretaria Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (grant COL-07-045) and ICGES. Special thanks to personnel of the Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente, Parque Municipal Summit and Autoridad del Canal de Panama by the permission. To Red Iberoamericana de Investigación y Control de Enfermedades Rickettsiales (RIICER). Additionally, we acknowledge to INTA and CONICET for the financial assistances to SN.

REFERENCES

1. Bowman AS and Nuttall PA. Ticks biology, disease and control, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [ Links ]

2. Dunn LH. The ticks of Panamá, their hosts, and the disease they transmit. Am J Trop Med 1923; 3:41-104. [ Links ]

3. Fairchild GB, Kohls GM, Tipton VJ. The ticks of Panama (Acarina: Ixodoidea). In: Wenzel WR and Tipton VJ editores. Ectoparasites of Panama. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History; 1966; 167-219. [ Links ]

4. Bermudez SE, Miranda RJC, Smith DC. Ticks species (Ixodida) in the Summit Municipal Park and adjacent areas, Panama City, Panama. Exp Appl Acarol 2010; 52(4):439-48. [ Links ]

5. Bermudez SE, Miranda RJC. Distribution of ectoparasites of Canis lupus familiaris L. (Carnivora: Canidae) from Panama. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2011; 16(1):2274-2282. [ Links ]

6. Bermudez SE, Castro A, Esser H, Liefting Y, García G, Miranda RJ. Ticks (Ixodida) on humans in Panama, Panama (2010-2011). Exp Appl Acarol 2012; 58(1):81-881. [ Links ]

7. Murgas IL, Castro AM, Bermúdez SE. Current status of Amblyomma ovale (Acari: Ixodidae) in Panama. Ticks and Tick-Borne Dis 2012; 4(1-2):164-166. [ Links ]

8. Cooley RA. The genera Boophilus, Rhipicephalus, and Haemaphysalis (Ixodoidea) of the New World. Bull Nat Inst Health 1946; (187):1-54. [ Links ]

9. Kohls GM. Records and new synonymy of new world Haemaphysalis ticks, with description of the nymph and larva of H. juxtakochi Cooley. J Parasitol 1960; 46:355-361. [ Links ]

10. Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Peña A, Keirans JE & Robbins RG. Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of the Neotropical Zoogeographic Region. Special Publication, International Consortium on Ticks Tick-borne Diseases Atalanta, Houten, The Netherlands 2003; 173:80-81. [ Links ]

11. Holdridge L. Life zone ecology. San Jose, Costa Rica: Trop. Sci. Center; 1967. [ Links ]

12. Saracco F, DeSante D, Alvarez C, Morales S, Milá B, Kaschube D, Michel N. Monitoreo de sobrevivencia invernal aparente de aves migratorias en el Neotrópico: Informe preliminar sobre los primeros dos años (2003-04) del programa Monitoreo de Sobrevivencia Invernal (MoSI). California: The Institute of Birds Populations; 2004. [ Links ]

13. Nava S, Guglielmone AA. A meta-analysis of host specificity in Neotropical hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Bull Entomol Res 2013; DOI: 10.1017/S0007485312000557. [ Links ]

14. Springer M, Carver A, Nielsen C, Correa N, Ashmore J, Ashmore J, Lee J. Relative abundance of mammalian species in a central Panamanian rainforest. Rev Lat Conserv 2013; 3(1):19-26. [ Links ]