Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista MVZ Córdoba

Print version ISSN 0122-0268

Rev.MVZ Cordoba vol.19 no.2 Córdoba May/Aug. 2014

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Foraging density for squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus in two forests in Puerto Lopez - Colombia

Densidad de forrajeo para el tití Saimiri sciureus en dos bosques de Puerto López - Colombia

Jorge Astwood R,1 Biol, José Rodríguez P,2 M.Sc, Karen Rodríguez-C,3* M.Sc.

1Universidad de los Llanos, Km 12 Via Puerto Lopez, Villavicencio-Meta, Colombia.

2Universidad de los Llanos, GIRGA research group, Km 12 Via Puerto Lopez, Villavicencio-Meta, Colombia.

3Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Laboratório de Biodiversidade Molecular e Conservação. R. Washington Luis, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo - Brazil.

*Correspondence: karengiselle2004@gmail.com

Received: September 2013; Accepted: January 2014.

ABSTRACT

Objective. Forest remnants were analyzed to determine the density of squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) and the degree of alteration of the forest, by selecting areas for the conservation and maintenance of the species in natural environments. Materials and methods. Linear transects were conducted on two wooden fragments, “La Reforma” and “Campo Hermoso” farms (Puerto Lopez, Meta, Colombia), recording sightings of squirrel monkeys and identifying the tree species used by the primates. Results. The fragments studied correspond to trails at the edge of water bodies with low connectivity. Highest density values were observed on the second transect of La Reforma, a possible consequence of an overcrowding phenomenon due to the high degree of isolation of the fragment. The species preferentially used as refuge and food source were: Bellucia grossularioides, Eugenia jambos, Inga alba, Mauritia flexuosa, Pseudolmedia laevis and Rollinia edulis. Conclusions. The phenology of the plant species allows for a dynamic food supply, considering the constant availability of food for the primates. Therefore, despite the evident ecological problem of these forests, it is possible to use active restoration programs to strengthen the existing dynamics and balance the biogeochemical dynamics of the ecosystem, so that socioeconomic human activities are not in conflict with conservation efforts and vice versa.

Key words: Food, conservation, population density, dispersion, refuges (Source: ASFA).RESUMEN

Objetivo. Fueron analizados remanentes boscosos para determinar la densidad del Tití (Saimiri sciureus) y el grado de alteración del bosque, pretendiendo seleccionar áreas para conservación y mantenimiento de la especie en ambientes naturales. Materiales y métodos. Se realizaron transectos lineales en dos fragmentos boscosos, Hacienda La Reforma y Campo Hermoso (Puerto López, Meta-Colombia), registrando avistamientos del Tití e identificando las especies de árboles utilizadas por los primates. Resultados. Los fragmentos estudiados son senderos a la vera de cuerpos de agua con baja conectividad. Se observaron mayores valores de densidad en el segundo transecto de La Reforma; posiblemente como consecuencia de un fenómeno de sobrepoblación, debido al alto grado de aislamiento del fragmento. Las especies utilizadas preferencialmente como refugio y fuente alimenticia son: Bellucia grossularioides, Eugenia jambos, Inga alba, Mauritia flexuosa, Pseudolmedia laevis y Rollinia edulis. Conclusiones. La fenología de las especies de plantas permite un abastecimiento de alimento dinámico, considerando la disponibilidad constante de alimento para los primates, permitiendo afirmar que a pesar del evidente problema ecológico de estos bosques es posible utilizar programas de restauración activa para fortalecer la dinámica existente y equilibrar la dinámica biogeoquímica del ecosistema, para que las actividades antrópicas socio-económicas no estén en contraposición a la conservación y viceversa.

Palabras clave: Alimento, conservación, densidad poblacional, dispersión, refugios (Fuente: ASFA).INTRODUCTION

The squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus, Cebidae) is a primate species with a wide distribution in Colombia. Reports for the region of Llanos Orientales indicate that they are located in the foothills of the East Andes, from 1500 m.a.s.l. to the Colombian Amazon forest and the banks of the Orinoco River (1).

Defler (1) has reported that the species occupies different types of forests, mainly gallery forests and even palm groves. Within these it frequently uses all arboreal strata for moving, foraging and refuge.

While the classification for the species by the IUCN (2) is of low risk and it is found in appendix II in the CITES, there is still a large concern in the department of Meta since this species has the highest rates of illegal capture within primates, from their natural sites to be sold as pets. Likewise, the threat of the implementation of agricultural crops, livestock activities, tourism development, human settlements and forest fragmentation has been noted (3).

In the year 1970 5,563 individuals were legally exported from Colombia to other sites of the world, illegal exports could double this number (4). Hence the need to study them in the field, in order to know their phylogeographic, ecological aspects and the composition of the habitat necessary for their survival (5).

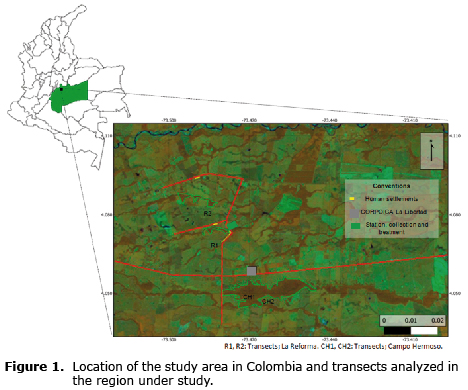

Under these conditions, the research was developed in two forest remnants, La Reforma and Campo Hermoso farms in the vicinity of the municipality of Puerto Lopez (Meta, Colombia), I order to learn population-related aspects and the habitat of the squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus, as a tool for the selection of areas for their conservation (Figure 1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

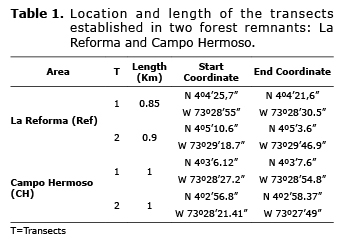

Data collection. The density of the squirrel monkey in each forest was estimated using the method of linear transects of variable width (6). Two trenches were placed in each of the forest, La Reforma and Campo Hermoso, separated by a minimum of 500 m (Table 1).

The access roads, human settlements and soil uses were identified in each forest (Figure 1). A sampling point was established in each observation, which was demarcated during the walks for the estimation of density.

The journeys to the samplings sites were carried out three days a week, twice a day, at 0500 HR and at 1000 HR and between 1400 HR and 1600 HR, since the activity peaks of the squirrel monkey occur at these hours (3.7). The walks were made at an average speed of 0.5 km/hour.

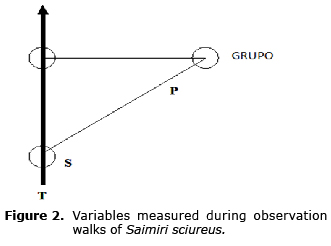

The following information was recorded on each journey: perpendicular distance (P): animal detected to the transect line; radial distance (S): distance of the observer when detecting the animal (Figure 2); time of detection; distance in the transect; number of individuals and number of troops.

Statistical analysis. The size and shape of the patches, degree of isolation, scattering, interaction and heterogeneity were evaluated through digital cartographic analysis of the vegetation cover map of the IGAC (8) and Landsat images (Figure 1) in order to estimate the degree of alteration in each forest.

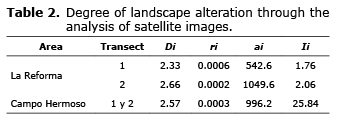

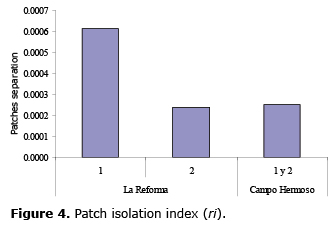

Each of the above named features were calculated through indexes: shape index (Di) that connects the size and shape of patches; isolation index of a patch (ri) which connects the distance between patches; isolation index of all patches (ai) which shows the degree of isolation of all patches and also the interaction index between patches (Ii), all such calculated according to the formulas proposed by Gonzalez et al (9).

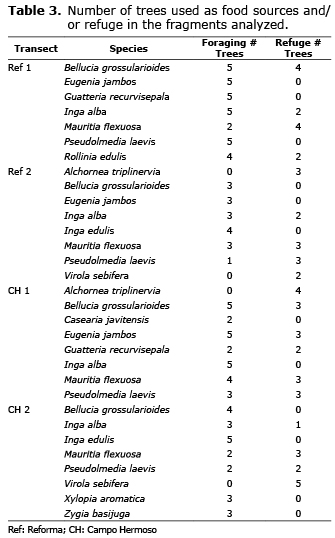

Identification of flora. The tree species used by primates and the plant composition they were feeding from (fruit, young leaves or flowers) were marked and identified using the methodology employed by Dueser and Shugart Jr (10), the species preferentially used as refuge were also identified. The height in the tree or shrub at which the animals were found and the activity carried out at the time of the observation (11) were noted in each sighting. Some trees that provided food were marked to perform phonological follow-up.

RESULTS

The forest fragments studied were limited to small trails on the edge of water bodies that, in most cases, were not even within the provisions of the Law in terms of conservation and maintenance of vegetation around streams as provided for by Decree 877/1976 issued by the Ministry of Agriculture of Colombia. The patches showed irregular shapes mainly due to the high intervention to which they are subjected in addition to the low connectivity between the same (Figure 1). In the vicinity of these forests, the land is mainly used for cattle ranching and the cultivation of African palm. In addition, in the proximity to the forest of La Reforma there is an hydrocarbon processing plant.

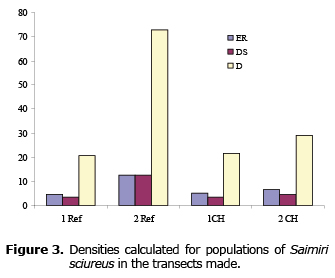

The results for the rate of encounters (ER), estimated density of the troops (DS) and density of animals per hectare in each sampling area (D) are listed in figure 3. The highest values for the three variables were observed in transect number two of La Reforma. However, it is possible that there is some overpopulation phenomenon occurring there.

When analyzing the rates of encounter of troops or groups calculated for each area, a tendency to increase in proportion to the perpendicular distance in meters was observed.

Within the alteration indices of forest fragments, the shape index (Di) showed that the fragments analyzed had an irregular shape and were far from Euclidean parameters (Table 2). In terms of the isolation between patches (ri), it was observed that the fragment where transect 1 of La Reforma is located showed the greatest separation with neighboring patches (Figure 4).

However, the isolation index of all patches (ai) showed that the area with the greatest isolation with all patches within the landscape is the fragment where transect 2 of La Reforma is located. Finally, the index of interaction between patches (Ii) allowed detecting that the fragment of Campo Hermoso had the greatest degree of interaction with its neighboring patches when compared with other fragments analyzed.

During the walks of the transects it was found that the species preferentially used as refuge and as food source were: Bellucia grossularioides, Eugenia jambos, Inga alba, Mauritia flexuosa, Pseudolmedia laevis and Rollinia edulis (Table 3).

It is worth noting that during the passing of time, most species are changing their phenological condition asynchronously, for this reason, the supply of food for primates is dynamic in terms of the part of the plant available at a given time (flower, fruit, leaf), but constant in the sense that animals always have some resource for feeding, which is also relatively abundant.

DISCUSSION

Due to the low degree of conservation of the fragments, transects were established within vegetation strips round a body of water. Despite the fact that Buckland et al (6) recommend that transects are established perpendicularly to avoid having a bias toward the greater abundance of resources in said strips, it was not performed in this way because transects are located in open areas of grasslands where it is not possible to collect data related to the density of primates. Similarly, the area was not enough to locate the five trenches proposed, separated at least by 500 meters.

With regard to the conditions of conservation of the forests, the establishment of cattle farms in the area of La Reforma typifies the area as of high intervention with forest presence between 11-20% of the landscape and in the area of the farm Campo Hermoso, and as of low intervention with forest presence of 31-40%. Such information is consistent with what was observed in the results obtained during this study, being directly related to the density values obtained (Figure 3). Thus, the density of specimens per hectare in two transects of Campo Hermoso (21.6 and 29 animals/Ha) is more in line with the amounts of the available habitats than in the area of La Reforma (20.6 and 72.7 animals/Ha) if taking into account that the area of the latter is substantially smaller.

If strictly observing the numbers of the rates of encounters and density in the area of La Reforma, especially in the transect 2, it may be possible to think that by having a density close to and/or above that of Campo Hermoso, the condition of the populations is more favorable; however, the high values for the shape index (Di), the isolation index with respect to a patch and all patches (ai) and the interaction index (Ii) (Table 2), allow observing the little connectivity of vegetation fragments in La Reforma and therefore argue that rather than a higher density of individuals per area unit, what is observed is a clear process of overcrowding due to the high reproduction capacity of Saimiri sciureus (12, 13). As the gaps of small forests grow larger, there is an increase in the rates of extinction and a decrease in the recolonization by fragmentation of the habitat (14). Even under unfavorable conditions; this is a phenomenon that could trigger, in the short term, health problems within the population, with a potential risk for human beings in terms of public health

The troops of primates registered in transect 2 of La Reforma showed a higher average in the perpendicular distance of troop detection, this phenomenon may be related to increased competition for resources (12) and possible stress levels that this produces on animals, which are more cautious when there are humans walking through the forest floor, therefore they keep themselves farther away.

In terms of availability of resources, in the area of La Reforma, 10 tree species were recorded, belonging to eight families divided in the two transects. Likewise, there were 12 species in the area of Campo Hermoso belonging to 9 families. Defler (1) and Williams et al (12), reported that Saimiri sciureus exploits the food resources of the families Moraceae, Fabaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Melastomataceae, Annonaceae and Myrtaceae, among others, these observations are consistent with those made in this study, in which it was observed that species of the genera Bellucia (Melastomataceae), Eugenia (Myrtaceae), Guateria (Annonaceae), Inga (Fabaceae), Mauritia (Arecaceae), Pseudolmedia (Moraceae), Rollinia (Annonaceae), Alchornea (Euphorbiaceae), Virola (Myristicaceae), Casearia (Flacourtiaceae), Xylopia (Annonaceae) and Zygia (Fabaceae), alternate their phenological stages, allowing the primate troops to enjoy a variety of food resources over time in Gallery forests with a lot of obstacles to predators and a adequate supply of insects, bats and lizards (15), as it occurs in agricultural landscapes (Table 3).

Coupled to this and although the graphics show, at first glance, some differences in the availability of food resources and shelter, no significant differences were found (p>0.05) in the means of any of the variables. This means that S. sciuerus uses all resources available on an equitable basis and for the results of this study there is no trend or marked preference towards any of them, neither for food nor shelter.

The relationship between abundance, frequency, dominance and basal area is proportional, which indicates that all species have a significant degree of importance to the structure of the patches and each species is therefore fundamental for the maintenance of the populations of S. sciureus.

The disappearance or isolation of primates entails important consequences since in their trophic niche they are important dispersers of seeds and modify the composition and distribution of forests. In addition, they have a very important role as insect controllers (3).

The serious transformation and fragmentation processes to which the forests and ecosystems of the area have been subject to were evident during the development of this study. This aspect is a neuralgic point and must be the epicenter of the conservation efforts, i.e. the permanence and health of the species’ population, not only of primates, but the rest of the fauna and flora inhabiting these forests, depends mainly on the implementation of strategies for the restoration of connectivity and the reestablishment of biological corridors that allow the networks for the transfer of energy and biomass of the system to work properly.

The size of squirrel monkey troops is positively associated with the percentage of the tree component, fruit supply, wet areas and the density of the edges in the ecotone and negatively with the presence of other primates, predators or the absence of insects (3). By preferring the secondary habitat, the mix of forests in different succession stages increases the vulnerability of the species by the presence of man and the indiscriminate use of agrochemicals.

Finally, the results obtained in terms of phenological and structural dynamics in the forest fragments under study allow establishing that despite the obvious ecological problem of these forests, it is still possible to induce nature through active restoration programs for strengthening the existing dynamics and balance the biogeochemical dynamics of the ecosystem in a relatively short period of time, so that the socioeconomic human activities already established supporting the population are not contrary to the conservation efforts and vice versa.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of agreement 28205-007, Minutes 03. Cormacarena - Research institute (IIOC) of Universidad de los Llanos. The authors also thank Javier Hernandez (r.i.p.), for his fieldwork and Mauricio Torres M. for his unconditional support.

REFERENCES

1. Defler TR. Historia natural de los primates colombianos. 2da edición. ed. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias. Departamento de Biología; 2010. [ Links ]

2. IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources; 2003. Available URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41537/0. [ Links ]

3. Solano D, Wong G. Hábitat y población de mono tití (Cebidae: Saimiri oerstedii oerstedii) en la península de Osa, Costa Rica. Ambientales 2009; 38:33-46. [ Links ]

4. Ruiz-García M, Leguizamón N, Vásquez C, Rodríguez K, Castillo MI. Métodos genéticos para la reintroducción de monos de los géneros Saguinus, Aotus y Cebus (Primates: Cebidae) decomisados en Bogotá, Colombia. Rev Biol Trop 2010; 58(3):1049-67. [ Links ]

5. Ruiz-García M, Castillo MI, Álvarez D, Gardeazabal J, Borrero LM, Ramírez DM, et al. Estudio de 14 especies de primates platirrinos (Cebus, Saimiri, Aotus, Saguinus, Lagothrix, Alouatta y Ateles), utilizando 10 loci microsatélites: análisis de la diversidad génica y de la detección de cuellos de botella con propósitos conservacionistas. Rev Orinoquia 2007; 11:19-37. [ Links ]

6. Buckland ST, Plumptre AJ, Thomas L, Rexstad EA. Design and analysis of line transect surveys for primates. Int J Primatol 2010; 31(5):833-47. [ Links ]

7. Leonardi R, Buchanan-Smith HM, Dufour V, MacDonald C, Whiten A. Living together: behavior and welfare in single and mixed species groups of capuchin (Cebus apella) and squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). Am J Primatol 2010;72(1):33-47. [ Links ]

8. IGAC. Cartographer Cobertura y uso de las Tierras. [en linea]. Colombia: IGAC; 2005. URL Disponible en: http://geoportal.igac.gov.co/ssigl2.0/visor/galeria.req?mapaId=9&title=Cobertura%20uso%20de%20la%20tierra.

9. González DU, Estrada E, Cantú-Ayala C. Análisis de fragmentación en colonias del perrito llanero mexicano (Cynomys mexicanus). Ciencia-UANL 2012; 15(57):43-9. [ Links ]

10. Dueser RD, Shugart Jr HH. Microhabitats in a forest-floor small mammal fauna. Ecology 1978; 59(1):89-98. [ Links ]

11. Gómez-Posada C. Dieta y comportamiento alimentario de un grupo de mico maicero Cebus apella de acuerdo a la variación en la oferta de frutos y artrópodos, en la Amazonía colombiana. Acta Amazónica 2012; 42(3):363-72. [ Links ]

12. Williams LE, Brady AG, Abee CR. Squirrel monkeys. The UFAW Handbook on the Care and Management of Laboratory and Other Research Animals, Eighth Edition 2010: 564-78. [ Links ]

13. Trevino HS. Seasonality of reproduction in captive squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). Am J Primatol 2007; 69(9):1001-12. [ Links ]

14. Manel S, Schwartz MK, Luikart G, Taberlet P. Landscape genetics: combining landscape ecology and population genetics. Trends Ecol Evol 2003; 18(4):189-97. [ Links ]

15. Guisan A, Thuiller W. Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol Lett 2005;8(9):993-1009. [ Links ]