Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista MVZ Córdoba

Print version ISSN 0122-0268

Rev.MVZ Cordoba vol.19 no.3 Córdoba Sept./Dec. 2014

ORIGINAL

Serological survey for equine viral arteritis in several municipalities in the Orinoquia region of Colombia

Monitoreo serológico de arteritis viral equina en municipios de la Orinoquia, Colombia

Agustín Góngora O,1* Ph.D, María Barrandeguy,2 Ph.D, Karl Ciuoderis A,3 MVZ.

1Universidad de los Llanos, School of Animal Sciences, Reproduction and Animal Genetics Investigation Group, Villavicencio, Km. 12 Vía Puerto López, Meta, Colombia.

2Universidad del Salvador, Infectious Diseases Department, Veterinary Career and Equine Virus Laboratory, Institute of Virology CICVyA INTA. Av. Callao y Córdoba (C1023AAB) Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

3Wisconsin-Madison University, Department of Pathobiological Sciences, Veterinary Medicine School, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

*Correspondence: agongora@unillanos.edu.co

Received: October 2013; Accepted: April 2014.

ABSTRACT

Objective. The goal of this study was to determine the current status of the Equine Arteritis virus (EAV) in horse populations in the Orinoquia region of Colombia. Materials and methods. A transversal study was conducted by serological survey of equine (n=100) from 11 municipalities of the Colombian Orinoquia region. Serum samples were tested by virus seroneutralization assay according to the guidelines provided by the World Organization for Animal Health. Results. After testing was carried out no positives samples to EAV were found in the population analyzed. Conclusions. Although the sample size of the population screened in this study does not represent the total equine population size for the region or the country, data obtained has shown the absence of EAV infection in these animals. However, a wider study area including other regions of the country, with a feasible statistical design, would determine if this infection continues to be an exotic disease for Colombia.

Key words: Antibodies, epidemiology, prevalence, virus (Source: DeCS).

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Determinar la condición sanitaria relativa a la infección con el virus de la arteritis (VAE) en equinos de la Orinoquia, Colombia. Materiales y métodos. Se realizó un muestreo serológico transversal en equinos (n:100) provenientes de 11 municipios, de la región de la Orinoquia, Colombia. Los sueros fueron analizados por la técnica de seroneutralización viral de acuerdo con lo recomendado por la Organización Internacional de Sanidad Animal (OIE). Resultados. No se identificaron reactores al VAE en la población analizada. Conclusiones. Si bien la población estudiada no representa el total de los equinos de la región, ni del país, los datos obtenidos evidencian la ausencia de infección por VAE en estos animales. Un estudio ampliado, estadísticamente diseñado, incluyendo otras regiones del país permitiría determinar fehacientemente si esta infección continua siendo exótica para Colombia.

Palabras clave: Anticuerpos, epidemiología, prevalencia, virus (Fuente: DeCS).

INTRODUCTION

The arteritis virus is a widely diffused infectious disease around the world that, in addition to affecting equines, affects donkeys, mules and zebras. It is produced by a RNA virus of the Arteriviridae family of the Nidoviral order that includes three other virus; the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRVS), the simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) and the murine lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus (LDV) (1).

The name of the disease is associated with inflammatory lesions in the veins, especially the arterioles (2), and has been reported in North And South America, Europe, Asia, Australia and Africa, with the exception of Iceland and Japan (3), and more recently in New Zealand (4). Seroprevalence varies considerably from country to country and among breeds (5).

The infection can be asymptomatic (in the majority of cases) or present several symptoms such as fever, loss of appetite, nasal secretion, and conjunctivitis, which are similar to those caused by other respiratory virus (influenza or equine herpes virus 1 and 4). Some other clinical signs can be present such as pruritus, edema of the scrotum or mammary glands, and abortions (6). After an acute infection in sexually mature males, between 30-50% of the animals can maintain a persistent infection and the virus is expelled with semen (7). These animals become the principal disseminators of the virus, whether in the short or medium term or for the rest of their lives, becoming the greatest threat to free populations (5). The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) included it in the unique list of diseases of compulsory notification for land and marine animals since its presence restricts commerce between countries (8).

Colombia is not presently aware of the presence of this disease; however, identification of herpes virus 1 and 4 reactors (9) that presents clinical symptoms similar to EAV, importing animals from countries where the disease has been reported in addition to the possible illegal entry of persistently infected animals over the extensive land borders increases the probability that this infection is present in the country and is not being diagnosed by the health authorities and veterinarians.

In the Orinoquia region equines are a valuable resource for managing extensive livestock and more recently due to the popularity of sporting and recreational activities which have caused a notable increase in the equine population. The objective of this study was to determine the presence of EAV serological reactors in the equine population of this region that constitutes 38% of the Colombian territory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

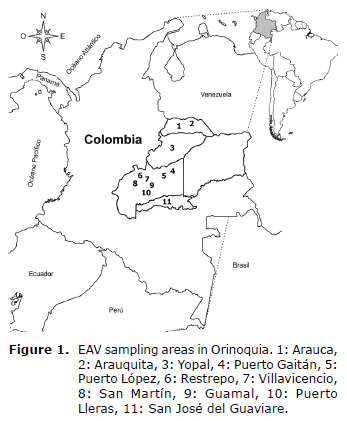

Animals. A transversal sampling was done with a selected group of 100 equines from the municipalities of Villavicencio (n=19), San Martin (n=10), Restrepo (n=10), Puerto López (n=10), Puerto Lleras (n=10), Yopal (n=10), Arauquita (n=7) Arauca (n=3), Puerto Gaitán (n=10), San José del Guaviare (n=10) and Guamal (n=1), (Figure 1). The animals came from 22 farms and the following breeds: Silla Argentina 10 (10%), Quarter Horse 12 (12%), criollo 74 (74%), mule 3 (3%) and Percheron 1 (1%). Distribution by sex of the adult animals was 47 males and 53 females. The municipalities that the animals came from are found in the 4 departments of the subregion known as Los Llanos Orientales.

5 ml of blood from each animal was taken from the jugular vein in ad-hoc vacuum tubes (vacutainer®), after clot retraction it was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes, the resulting serum was fractioned by duplication in aliquots of 1 ml into plastic Ependorff® tubes and maintained at -70°C until processed.

Viral neutralization test. The serum was processed at the Institute of Virology - Veterinary and Agronomic Investigation Center (INTA-Argentina) using the microseroneutralization technique for EAV virus (Arvac vaccination strain). Equine serums of international reference were used as positive and negative controls, provided by Dr. P. Timoney from The Gluck Equine Research Center (Kentucky University, USA) following the procedure described in the OIE manual (10). Briefly, the equine serums were inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes and were then diluted in a cellular culture (MEM E) in base two dilutions from 1:2 to 1:256 and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with a virus suspension that contained 100 DICT 50%/ml. After incubation a cellular suspension was added that contains 10000 cells (RK13) per ml. All this was done in microplates for cellular cultures of 98 plates. Controls were carried out to confirm the title of the virus and a strong positive control, a weak one, and a negative serum were incorporated into the study. The reaction was read in an inverted microscope at 100 magnification where the cytopathic effect produced by the non-neutralized virus was determined. The antibody title of a determined serum was expressed as the inverse of the maximum dilution of serum that totally “neutralized” the 100 DICT 50%/ml of viral equine Arteritis virus.

RESULTS

All of the analyzed samples (100/100) were negative for seroneutralization for detecting EAV antibodies.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained infer that EAV is not present in the equine population in the region, this being the first study done in Colombia that tries to indirectly determine the presence of EAV. In spite of the number of breeds included in the sampling and the varied origin of the animals, the absence of reactors indicates that these animals have not been in contact with the virus. Similarly, due to the small amount of animals sampled, the need for a new study in a statistically determined population that allows a greater certainty of the EAV health situation in the country is considered.

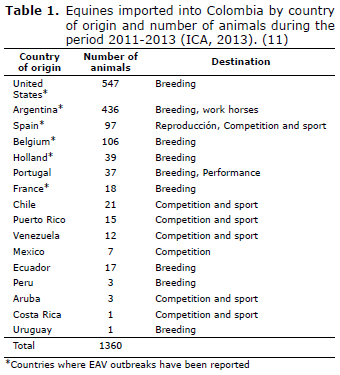

In Colombia, importing equines and semen has been continually increasing in recent years. In 2008 1.212 animals and 400 semen doses were imported, and in 2009 1.436 animals and 1.548 semen doses were imported, in 2010 1,004 animals were imported. This tendency was maintained through 2011-2013, with the entry of 1.347 animals, the majority of them for competitions, recreation or breeding (Table 1), (11). The introduction of imported animals occurred by air at the El Dorado airports (Bogota) and José María Córdoba (Rionegro-Antioquia) and their final destination were the departments of Cundinamarca and Antioquia, where the greatest population of equines in the country is, far from where this study was performed.

In Colombia a large number of imported animals or frozen semen comes from countries that have reported EAV outbreaks, such as Argentina (12), the European Union (13), France, (14), Spain (15), Holland (16) and Belgium (17), which carries the potential risk of introducing persistently infected animals or infected frozen semen. An example that illustrates this situation is the entry of the virus into Argentina through frozen semen from Holland on more than one occasion (12, 18). In another example the first outbreak occurred in the United Kingdom was due to importing a horse from Eastern Europe that had the virus (19). An EAV outbreak in the Normandy region in France (20) had a similar origin. In Italy an outbreak was reported associated with a horse imported from Germany that was seronegative, but after remaining for a time on the farm it presented seroconversion and later the virus was isolated from the semen (21). Lastly, the most recent outbreak in the United Kingdom occurred due to the entry of an animal infected in a breeding center (22).

Another aspect that merits analysis is the increase in the national commercialization of semen. Although the requirements to register technical units related to verifying the quality of seminal material and auditing semen and embryo production centers were established by means of ICA's Resolution 01426 from 2002 (23), said regulation is not complied with since there are few artificial insemination (AI) and embryo transfer centers. Resolution 02820 of 2001 regulates the technical control of producing, importing, and commercializing semen and embryos (24). The above shows that a large part of obtaining and commercializing semen is done among farms, without the supervision of health authorities.

This fact suggests the need to constantly monitoring donor animals, which should be done with a permanent diagnostic support, whether through the official sanitary authorities or universities. In this respect, certain countries require semen donor animals to be seronegative or viral isolation tests performed on the semen for those that are seropositive (3), requirements that are not met by the breeders in the country.

Within the breeds included in this study, samples come from the municipality of San Martín, belonging to the Silla Argentina breed. In 2009 1000 horses from this country were imported, however in 2010 ICA temporarily suspended importations for 6 months due to a state of alert concerning EAV outbreaks (25). In spite of this precedent, there was no evidence of the presence of virus reactors in these imported animals. The absence of reactors in this group also shows that these animals had not been vaccinated.

Another area of concern was along the extensive border with Venezuela, close to the Arauca and Arauquita municipalities where 10% of the samples were from; however, the results were also negative. The need for new studies in other municipalities along the border is seen, since the presence of the virus in the neighboring country is not clear. A preliminary study of 1008 samples in 5 states in the center of the country showed a prevalence of 2.48% (26).

The equine population in Colombia is estimated to be at about 1.533.432 animals (27); therefore the presence of this disease would be devastating for the national industry. In countries that have suffered the effects of this disease the direct economic loss has been associated with abortions, death of young animals, loss in the commercial value of the breeders, reduction in the demand for semen, vaccination costs, cancelation of equine events and international markets (3,28). There is a need for active surveillance regarding the presence of this disease in the country.

There is no evidence of EAV infection in the analyzed population, which is to say that these animals have not had contact with the EAV virus. These results are very encouraging; however new studies are required in a wider population that can be extended to other regions of the country to confirm the state of this exotic disease in Colombia.

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgement

Dra. Piedad Cristina Rivas from the Universidad de la Salle for supporting in obtaining the samples. María Roció Parra Molina for managing and preserving the samples.

REFERENCES

1. Balasuriya UBR, MacLachlan NJ.The immune response to equine arteritis virus:potential lessons for other arteriviruses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2004; 102:107-129. [ Links ]

2. Moore BD, Balasuriya UBR, Nurton JP, McCollum WH, Timoney PJ, Guthrie AJ et al. Differentiation of strains of equine arteritis virus of differing virulence to horses by growth in equine endothelial cells. Am J Vet Res 2003a; 64:779-784. [ Links ]

3. Bell SA, Balasuriya UBR, MacLachlan J. Equine Viral Arteritis. Clin Tech Equine Pract 2006; 5:233-238. [ Links ]

4. McFadden AM, Pearce PV, Orr D, Nicoll K, Rawdon TG, Pharo H, et al. Evidence for absence of equine arteritis virus in the horse population of New Zealand. N Z Vet J 2013; 61(5):300-304. [ Links ]

5. Balasuriya UBR, Go YY, MacLachlan NJ. Equine arteritis virus. Vet Microbiol 2013; 167:93-122. [ Links ]

6. MacLachlan NJ, Balasuriya UB. Equine viral arteritis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2006; 581:429-433. [ Links ]

7. Guthrie AJ, Howell PG, Hedges JF, Bosman AM, Balasuriya UBR, McCollum WH et al. Lateral transmission of equine arteritis virus among Lipizzaner stallions in South Africa. Equine Vet J 2003; 35:596-600. [ Links ]

8. Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE). Enfermedades, infecciones e infestaciones de la Lista de la OIE en vigor en 2013. [Fecha de acceso Octubre de 2013]. URL Disponible http://www.oie.int/es/sanidad-animal-en-el-mundo/enfermedades-de-la-lista-de-la-oie-2014/. [ Links ]

9. Ruíz Sáenz J Góez Y, Urcuqui S. Góngora A, López A, Evidencia serológica de la infección por herpesvirus equino tipos 1 y 4 en dos regiones de Colombia, Rev Colomb Cienc Pecu 2008; 21:251-258. [ Links ]

10. Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE). Código Sanitario para los animales Terrestres: Infección por el virus de la arteritis equina. Volumen II, titulo 12, capítulo 12.9, 21ª edición. OIE; 2012. [Fecha de acceso Noviembre 2013]. URL Disponible http://www.oie.int/index.php?id=169&L=2&htmfile=chapitre_1.12.9.htm. [ Links ]

11. Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario. Cantidad y valor de las importaciones de equinos autorizadas por el ICA e inspeccionadas por semestre y país de origen. Bogotá, Colombia; 2012. [Fecha de acceso diciembre de 2013]. ICA. URL Disponible http://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/cd82c461-9eb1-46d9-a5fd-b90c52e17399/Importacion-Equinas-2012.aspx. [ Links ]

12. Echeverría MG, Pecoraro MR, Galosi CM, Etcheverrigaray ME, Nosetto EO. The first isolation of equine arteritis virus in Argentina. Rev Sci Tech 2003; 22:1029-1033. [ Links ]

13. Zhang J, Timoney PJ. Shuck KM, Seoul G, Go YY, Lu Z, et al. molecular epidemiology and genetic characterization of equine arteritis virus isolates associated with the 2006-2007 multi-state disease occurrence in the USA. J Gen Virol 2010; 91:2286-2301. [ Links ]

14. Pronost S. Pitel PH, Miszczak F, Legrand L, Marcillaud-Pitel C, Hamon M, et al. Description of the first recorded major occurrence of equine viral arteritis in France. Equine Vet J 2010; 42(8):713-720. [ Links ]

15. Monreal L, Villatoro AJ, Hooghuis H, Ros I, Timoney PJ. Clinical features of the 1992 outbreak of equine viral arteritis in Spain. Equine Vet J. 1995; 27(4):301-304. [ Links ]

16. de Boer GF, Osterhaus ADME, van Oirschot JT, Wemmenhove R. Prevalence of antibodies to equine viruses in the Netherlands. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 1979; 104:65-74. [ Links ]

17. Vairo S, Vandekerckhove A, Steukers L, Glorieux S, Van den Broeck W, Nauwynck H. Clinical and virological outcome of an infection with the Belgian equine arteritis virus strain 08P178. Vet Microbiol 2012; 157:333-344. [ Links ]

18. Barrandeguy, M. EVA outbreak in Argentina. Equine Dis Quarterly 2010; 19:3-4. [ Links ]

19. Wood JL, Chirnside ED, Mumford JA, Higgins AJ. First recorded outbreak of equine viral arteritis in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec 1995; 136:381-385. [ Links ]

20. Miszczak F, Legrand L, Balasuriya UBR, Ferry-Abitbol B, Zhang J, Hans A, Fortier G, et al. Emergence of novel equine arteritis virus (EAV) variants during persistent infection in the stallion: Origin of the 2007 French EAV outbreak was linked to an EAV strain present in the semen of a persistently infected carrier stallion. Virology 2012; 423:165-174. [ Links ]

21. Barbacini S. An outbreak of equine arteritis virus infection in a stallion at a Trakehner studfarm. Equine Vet Educ 2005; 17(6):294-298. [ Links ]

22. Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE). Informaciones sanitarias. OIE; 2012. [Fecha de acceso Noviembre de 2013] URL Disponible http://www.oie.int/wahis_2/temp/reports/es_imm_0000012398_20121005_161133.pdf. [ Links ]

23. Resolución 01426. [en línea]. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA); 2002. [Fecha de acceso noviembre 2013] URL: http://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/413d1f7c-8079-42be-a643-439a209b394e/1426.aspx. [ Links ]

24. Resolución 02820. [en línea]. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA). 2001 [Fecha de acceso Noviembre 2013] URL: http://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/f0d736f9-c875-473e-8250-f0252dcaa7aa/2820.aspx. [ Links ]

25. Resolución 1595. [en línea]. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA). 2010 [Fecha de acceso Noviembre 2013]. URL: http://www.icbf.gov.co/cargues/avance/docs/resolucion_ica_1595_2010.htm. [ Links ]

26. Perozo E. Arteritis Viral Equina: Una Revisión. Rev Fac Cienc Vet 2005; 46(2):74-86. [ Links ]

27. Censo equino en Colombia. [en línea]. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA). [Fecha de acceso Enero de 2014] URL: http://www.ica.gov.co/Areas/Pecuaria/Servicios/Epidemiologia-Veterinaria/Censos-2013.aspx. [ Links ]

28. Holyoak GR, Balasuriya UBR, Broaddus CC, Timoney PJ. Equine viral arteritis: Current status and prevention. Theriogenology 2008; 70:403-414 [ Links ]