Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista MVZ Córdoba

Print version ISSN 0122-0268

Rev.MVZ Cordoba vol.20 supl.1 Córdoba Dec. 2015

CLINICAL CASE

Fatal parasitosis in blackbucks (Antilope cervicapra): a possible factor risk in hunting units

Parasitosis fatal en el antílope negro (Antilope cervicapra): un posible factor de riesgo en unidades de cacería

José Ortiz Ned de la Cruz-Hernández,1 M.Sc, Edgar López-Acevedo,1 M.Sc, Lorena Torres-Rodríguez,1 M.Sc, Gabriel Aguirre-Guzmán,1* Ph.D

1 Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Km 5 Carretera Victoria-Mante, Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, México.

*Correspondence: gabaguirre@uat.edu.mx

Received: April 2014; Acepted: February 2015.

ABSTRACT

In February 2012, a reproductive group of 60 adult blackbucks (Antilope cervicapra) from Veracruz, Mexico was relocated to hunting units in eastern and northeastern Mexico. Seven individuals died due to hemorrhagic parasitic, abomasitis and enteritis caused by Haemonchus spp., Setaria spp., and Trichostrongylids. Deaths were associated with hepatic necrosis, bilateral congestive distention of heart and fibrinonecrotic bronchopneumonia. Also Anaplasma marginale was identified. The blackbucks’ population displayed a general mortality rate of 11.67%, where 25% of total male and 9.62% of total female died. The mortality was controlled by segregation of all remaining blackbucks and the treatment for internal and external parasites (biting flies and ticks). After the treatment, no fatality cases related to parasitosis were recorded. The results presented here exhibit the high relevance of parasitosis as possible factor risk in the survival of tis specie.

Key words: Anaplasma marginale, antelope, diseases, hunting, parasite, trichostrongylids (Source:CAB).

RESUMEN

En febrero del 2012, un grupo de 60 individuos adultos reproductivos de antílope negro (Antilope cervicapra) provenientes de Veracruz, México fueron reubicado en unidades de cacería del este y noreste de este país. Siete individuos murieron presentando hemorragias parasíticas, abomasitis y enteritis ocasionadas por Haemonchus spp., Setaria spp. y Trichostrongylids. Las muertes estuvieron asociadas con necrosis hepática, distensión congestiva del corazón y bronconeumonía fibronecrótica, donde Anaplasma marginale fue identificada. La población de antílopes negros mostró un porcentaje de mortalidad del 11.67%, en donde el 25 y 9.62% de los machos y hembras totales murieron. La mortalidad fue controlada mediante el aislamiento de los antílopes negros restantes y un tratamiento contra parásitos internos y externos (garrapatas y moscas picadoras), lo cual controló las mortalidades y reveló la importancia de la parasitosis como factor de riesgo que afecta la sobrevivencia de esta especie.

Palabras clave: Anaplasma marginale, antílope, caza, enfermedad, parásitos, trichostrongylids, (Fuente:CAB).

INTRODUCTION

The blackbucks (Antilope cervicapra) are indigenous to the Indian subcontinent where their population has decreased for excessive hunting and loss of their natural habitat (1,2). The population of this specie is expected to decline in the next decade and a become vulnerable or threatened.

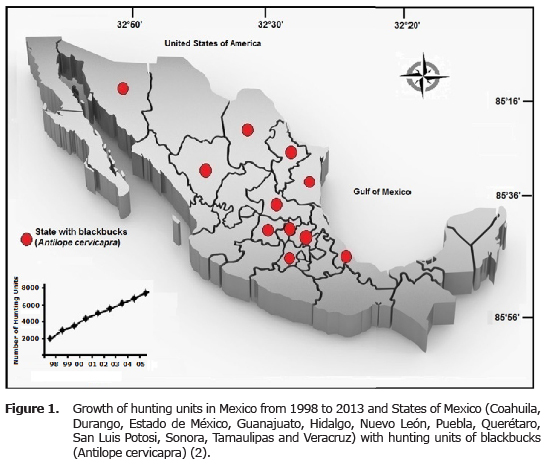

In Mexico (Figure 1) as in other countries, blackbuck has been introduced in hunting units, where they have increased their populations rapidly and have produced important economic resources as an exotic hunt product (1,3). Low information about the parasites diseases of exotic blackbucks in hunting units has been little studied (4). Some parasites as Amphistoma sp., Camelostrongylus mentulatus, Haemonchus contortus, Neospora caninum, Nematodirus spathiger, Oesophagostomum sp Strongyle sp., Strongyloides sp., Trichostrongylus axei, T. colubriformis, T. probolurus, Toxoplasma gondii and Trichuris have been identified and associated with disease and mortality of A. cervicapra (4-6). In Mexico, only one survey has been carried out involving a hunting unit with free-ranging blackbuck populations (7). Thus, the objective of this study was to describe a fatal parasitic disease associated with respiratory lesions in a hunting unit with free-ranging blackbucks re-located in northeastern, Mexico.

CASE HISTORY

Clinical findings. In February 2012, a group of 60 adult blackbucks (8 males and 52 females, 37-42 kg) was translocated for reproduction from the State of Veracruz, Mexico to a hunting unit with free-ranging animals in Padilla, Tamaulipas, Mexico (Figure 1). This area is located in the coordinates 24°03’N and 98°37’W and show 153 MASL, an average annual rainfall of 700 mm and an average annual of 22°C (ranging from 1 to 43°C).

Two weeks post-introduction to the grassland, seven blackbucks (two males and five females) presented an acute clinical history related with abdominal pain, feces with abundant mucus, hair loss, pale membranes (anemia), progressive wasting, prostration, seborrhea, skin lesions due to fly-bites, and weakness; however, the animals did not present fever. These clinical signs lasted for one week before the death of the blackbucks.

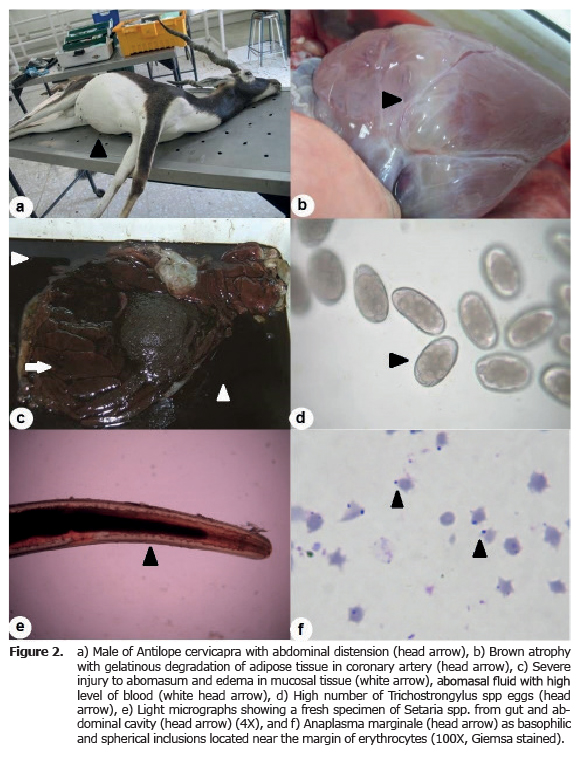

Pathological analysis. Dead animals were transported to the Pathology Laboratory of Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia of the Universidad Autonoma de Tamaulipas for diagnosis as part of the continuing cooperation with productive hunting unit and wildlife agency’ in Mexico (Figure 2a). Pathology evaluation was carried out in the seven blackbucks where main identified gross signs and histopathological lesions from different tissues (brain, hearth, liver, kidney, and tissues form digestive, respiratory and reproductive system) were analyzed according to standard protocol. Samples should be fixed in buffered formalin 10%, processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain. In addition, blood samples were collected from the sacrificed animals (lung and heart) and placed immediately on ice. EDTA was used as an anticoagulant and non-coagulated blood was tested, shortly after collection, for packed cells volume, and hemoglobin by microhematocit and spectrophotometry respectively. Also, blood samples were stained with Giemsa. Blood samples were fixed (1 min) in absolute methanol and stained with 10% Giemsa for 30 min. After staining, samples were washed three or four times with tap water to remove adhering stain and then air dried. The samples are examined under oil immersion to increased 700-1000 x.

CLINICAL RESULTS

The diseases impact in introduced wildlife species on local wildlife populations has become a recent issue of global priority, which is critical when disease risks involve the livestock industries and human health (1,8-10). The blackbucks (A. cervicapra) were introduced to Mexico for their importance as trophy hunting. The study population in the hunting unit consisted of 60 adult blackbucks (8 studs male and 52 reproductive females). The general mortality rate was 11.67%, but the sex-specific mortality rates were 25% (n=2) and 9.62% (n=5) for male and female, respectively.

Blackbucks dead animals presented paleness and jaundice of the mucosal membrane of the oral cavity, also hydrothorax, hydropericardium and ascitis were observed. Both atrophy with gelatinous degradation of adipose tissue in coronary artery, and an injury to abomasum and edema in mucosal tissue were detected (Figure 2b,c). The gross and histopathological lesions were consistent with a hemorrhagic parasitic abomasitis, catarrhal and hemorrhagic enteritis, hepatic necrosis, bilateral congestive distention of heart and fibrinonecrotic bronchopneumonia. Also, a high number of Trichostrongylids eggs were observed (Figure 2d). The examination of abdominal cavity show several parasitic structures, those were removed and identified under light microscopy as compatible with Haemonchus spp., Setaria spp. (Figure 2e), and Trichostrongylids. Consistent with other studies, the total burden of gastrointestinal nematodes was dominated by abomasal parasites characteristic for cattle and wild ruminants, i.e. Haemonchus spp. and Trichostrongylids (4,5,11). Both nematodes cause lesions consistent with injuries presented at necropsy of animals examined. While Setaria spp. not cause injury in to abdominal cavity (12).

The presence of endoparasites on blackbucks was 11.67% where a prevalence of 25.6 - 30% for Trichostrongylids and/or Haemonchus spp. were reported for California bighorn (Ovis canadensis califoriniana), Rocky Mountain bighorn (O. canadensis canadensis), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and sambar deer (Cervus unicolor) (9,11,13). Whereas studies and case reports of blackbucks reported prevalences of gastrointestinal nematodes ranging from 65 to 100% (4,5,11).

The hematological analysis revealed the presence of icteric animal with low values for packed cell volume and hemoglobin concentration (< 8 g dL-1) on blood samples; also, Anaplasma marginale (10-15 cells per camp) was detected at light microscopy examination with Giemsa-stained thin blood smears of meningeal and splenic vessels (Figure 2f). A. marginale usually infects cattle however exist reports in wildlife ungulates kept as hunting species by Mexican ranchers infected with this pathogen agent (14-15). This hemoparasite is present in populations of white-tailed deer from the northeast of Mexico where display a reported prevalence from 20.0 to 69.7% (7,15). The ectoparasites found in blackbucks dead animals were B. microplus and H. irritans. Both are consider as vectors for biological and mechanical transmission respectively (14,15,17). Our knowledge this is the first journal report of the presence of Setaria spp. and A. marginale in blackbucks (A. cervicapra) from hunting unit with in free-ranging.

Based on the findings of this report, we can hypothesize that blackbucks acquired parasites at their original location at the state of Veracruz, but the relocation process associated with stress, trauma, ticks, fly-bites and malnutrition are considered to have contributed to the death of the animals. Once the diagnosis was reached, the treatment measures were implemented for controlling and eradicating of diseases, and consisted of a strict segregation of all remaining blackbucks from any other animals, application of oxytetracycline (1 mL per 10 kg body weight) and oral Ivermectin (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a+22,23-dihydroavermectin B1b9) as treatment against internal and external parasites (biting flies and ticks). After these measures were carried out, no further fatality cases were present in blackbucks (A. cervicapra) for this hunting unit.

In conclusion the present case represents the first report of the presence of Setaria spp. and A. marginale in blackbucks (A. cervicapra) from hunting unit with in free-ranging. This findings may involve the blackbuks as reservoirs for A. marginale because exist the appropriated vectors for biological and mechanical transmission (14,15,17) Additionally, this case indicated the importance of monitoring levels of parasitic infection in hunting units or their respective free-ranging and may invite a more comprehensive study into the epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and prophylaxis of parasite diseases in wild mammals and their possible relation with domestic organisms.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Universidad Autonoma de Tamaulipas. The publication of this paper was supported by the Fondo Mixto de Fomento a la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica CONACYT - Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas (México).

REFERENCES

1. Álvarez-Romero JG, Medellín RA, Oliveras de Ita A, Gómez de Silva H, Sánchez O. Animales exóticos en México: una amenaza para la biodiversidad. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales; 2008. [ Links ]

2. Álvarez-Romero J, Medellín RA. Antilope cervicapra. Vertebrados superiores exóticos en México: diversidad, distribución y efectos potenciales. Distrito Federal (Mex). Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (SNIB-CONABIO). 2005 pp 1-16. Proyecto U020. [ Links ]

3. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Bases de datos SNIB-CONABIO. Proyecto U020. México. D.F. [ Links ]

4. Isvaran K. Female grouping best predicts lekking in blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2005; 57(3):283-294 [ Links ]

5. Fagiolini M, Lia RP, Laricchiuta P, Cavicchio P, Mannella R, Cafarchia C, Otranto D, Finotello R, Perrucci S. Gastrointestinal parasites in mammals of two Italian zoological gardens. J Zoo Wildlife Med 2010; 41(4):662-670. [ Links ]

6. Goossens E, Dorny P, Boomker J, Vercammen F, Vercruysse J. A 12-month survey of the gastro-intestinal helminths of antelopes, gazelles and giraffids kept at two zoos in Belgium. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4):303-312. [ Links ]

7. Sedlák K, Bártová E. Seroprevalences of antibodies to Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in zoo animals. Vet Parasitol 2006; 136(3-4):223-231 [ Links ]

8. Krausman PR, Bleich VC. Conservation and management of ungulates in North America. Int J Environ Stud 2013; 70(3):372-382 [ Links ]

9. Yaralioúlu S, Sahin T, Sindak N, Yurekli UF. Investigation of some hematologic and biochemical parameters in the serum of gazelles (Gazella subgutturosa) in Ceylanpinar, Sanliurfa, Turkey. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 2004; 28(2):369-372 [ Links ]

10. Guirisa ADM, Rojasc HNM, Berovidesc AV, Sosab PJ, Pereza EME, Cruzd AE, Chavezd HC, Mogueld AJA, Jimenez-Coelloe M, Ortega-Pachecof A. Biodiversity and distribution of helminths and protozoa in naturally infected horses from the biosphere reserve "La Sierra Madre de Chiapas", Mexico. Vet Parasitol 2010; 170(3-4):268-277 [ Links ]

11. Vázquez-Prats VM, Flores-Crespo J, Santiago-Valencia C, Herrera-Rodríguez D, Palacios-Franquez A, Liébano-Hernández E, Pelcastre-Ortega A. Frecuencia de nematodos gastroentéricos en bovinos de tres áreas de clima subtropical húmedo de México. Tec Pecua Mex 2004; 42(2):237-245 [ Links ]

12. Quiroz R.H. Parasitología y enfermedades parasitarias de animales domésticos. Ed. Limusa. México DF. 2005. [ Links ]

13. Contreras J, Mellink E, Martínez R, Medina G. Parásitos y enfermedades del venado bura (Odocoileus hemionus fuliginatus) en la parte norte de la Sierra San Pedro Mártir, Baja California, México. Rev Mex Mastozoo 2007; 11(1):8-20. [ Links ]

14. Fuente J, Ruybal P, Mtshali MS, Naranjo V, Shuqing L, Mangold AJ, Rodríguez SD, Jiménez R, Vicente J, Moretta R, Torina A, Almazán C, Mbati PM, Echaide ST, Farber M, Rosario-Cruz R, Gortazar C, Kocan KM. Analysis of world strains of Anaplasma marginale using major surface protein 1a repeat sequences. Vet Microbiol 2005; 119(2-4):382-390 [ Links ]

15. Rodríguez SD, García MA, Jiménez R, Vega C Molecular epidemiology of bovine anaplasmosis with a particular focus in Mexico. Infect Genet Evol 2009; 9(6):1092-1101. [ Links ]

16. Ditchkoff SS, Hoofer SR, Lochmiller RL, Masters RE, Van Den Bussche RA. MHC-DRB evolution provides insight into parasite resistance in white-tailed deer. Southwest Nat 2005;50(1):57-64. [ Links ]

17. Torres L, Almazán C, Ayllón N, Galindo RC, Rosario-Cruz R, Quiroz-Romero H, Gortazar C, de la Fuente J. Identification of microorganisms in partially fed female horn flies, Haematobia irritans. Parasitol Res 2012; 111(3):1391-1395. [ Links ]