INTRODUCTION

This bird species has a size range of 30.5 to 35.5 cm and a weight ranging from 180-355 g. It has medium-sized tail; blackish beak with white wax at the base, reddish or pink legs, amber eyes, dark as a juvenile. It has no sexual dimorphism. Plumage between individuals is variable, and has an original light gray pattern of color and two great black stripes in the wings, at the end of the tail a black strip, white rump and purple and green iridescences on the neck. However, most individuals can go from white or whitish with irregular reddish to black spots with primary feathers and a white tail 1,2. This columbiform species is monogamous, and has as a notorious behavior where the male protects the female and the nest, ensuring the survival of their progeny 3.

In natural environment it inhabits and nests in interior highlands and coastal cliffs; In urban environments it congregates in flocks that can have hundreds of individuals that usually move, fly and perch together. They are located on ceilings, shelves, ducts, drains, attics, domes, attics, in which they build their nests, composed of dry branches and herbs placed on a simple base 3,4.

As for their reproductive behavior, it is known that after 8 to 12 days of mating, the female places 1 or 2 eggs that hatch 18 days later; the young leave the nest at 6 weeks of age; they have short reproductive periods and can be effectively mated all year round, a reason that would partly explain their abundant populations 3.

Originally from a large area of Eurasia and Africa 1, its original distribution was specifically Africa (Cape Verde, Guinea, Mauritania, Senegambia), Asia (China, Gansu, Jilin, Shanxi) Great Britain, Portugal, Madeira Island, Azores), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand) 2. The pigeon (Columba livia domestica), known as domestic pigeon, dove of Castile, brave pigeon or zuro, is considered an introduced species, now domestic, of cosmopolitan distribution, which is raised in homes and kept as an ornate bird 5,6.

Regarding its status, it has: IUCN: LC (minor concern); In US Migratory Bird Act: no special status; In US Federal List: no special status; CITES: no special status. C. livia domestica has been classified as one of the worst urban birds in the world, since its effects include, in addition to the destruction of structures, a zoonotic risk 7.

These pigeons are zoonotically determined to be associated with 40 diseases of which 30 are transmissible to humans and 10 to domestic animals, and are therefore considered a serious public health problem. Generally, these diseases are transmitted through the dry excretions that are transported in the air or by direct contact with them 8,9.

Additionally, the domestic pigeon is associated with more than 60 ectoparasites, including siphonaptera and mites, it is possible that with their feathers and dust they contaminate and affect human health. Some of the diseases related to pigeons are: salmonellosis, psittacosis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, listeriosis, staphylococcosis and dermatosis, among others 3,10,11.

There is a lack of information regarding this species in anthropic environments, both epidemiologically and ecologically; In Colombia the studies related to this species are few 6,12-14, the existing population is unknown for most of the cities 13,15. The domestic pigeon is considered a serious urban problem to the degree that it is called “flying rat”, it is considered to be a harmful vertebrate 3.

In this work the population abundance and the feeding sources of C. livia domestica in the city of Santiago de Tolú, Sucre, Colombia, were determined as a diagnosis that later allows to propose an environmental management program, given the possible affectations that this Species by overpopulation can cause.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Area of study: The city of Santiago de Tolú, Sucre, Colombia, located at 9 ° 31’59 “N and 75 ° 34’59” O, was built in the urban area of the city of Santiago de Tolú, on the shores of the Gulf of Morrosquillo. Specifically, the surveys were carried out in an area between Carreras 2 and 4 with streets 15 and 16, downtown area of the city. With a total area of 240.000m2 (24ha), the study area is characterized by its occupation of residential and commercial premises and includes the main square (Figure 1). The coordinates of the sampling points are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Coordinates of the sampling points.

| Point | N | O |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9°31´26 | 75°35´00´´ |

| 2 | 9°31´31´´ | 75°35´41´´ |

| 3 | 9°31´20´´ | 75°34´72´´ |

| 4 | 9°31´18´´ | 75°35´10´´ |

Sampling: The total sampling method 16-19 was applied, worked during six months of 2015, three months in dry season: January to March, and three months in rainy season: September to November; A weekly count was performed for each point simultaneously, which is equivalent to a total of 24 samples in total for each point; With daily sessions from 06:00 to 08:00 hours, with counts timed every hour 13,14.

Sampling at simultaneous and timed fixed points was selected to guarantee the absence of sample mobilization between sampling sites 20. In addition, it was considered that the gregarious behavior of this species shows a high degree of congregation and permanence of individuals within their group 3. In parallel, noise levels were measured, with two readings per session at each sampling point at 07.00 and 08.00 hours, using a Svan 971®13 sound level meter.

Determination of food sources: In each of the points the places of deposit of domestic waste WERE verified through ocular inspection. Once located, we proceeded to classify their contents 21. There were 30 samples per set point, corresponding to 5 samples / month. The calculated representative sample was: (N = 75, p = 0.05, Alpha 90%, maximum error of estimate 5%). The determination of waste was done as follows: human food leftovers (SAH) and non-biodegradable waste (RND).

Information Analysis: The comparison of the variation in population between the sampled sites, workdays and the schedules in each one of the markets, was carried out using Fiedman’s Anova with a level of significance of 0.05. Also, the gross density and density per counting point 22-24 were estimated.

RESULTS

The number of individuals recorded per month and per site are presented in table 2. The calculated gross density, taking 185 individuals as total, was 7.71 ind / ha. The specific density for each site was: 1 = 9 ind / ha, 2 = 5.9 ind / ha, 3 = 6.1 ind / ha and 4 = 6.5 ind / ha.

Table 2 Number of individuals per month and per site.

| Site | January | February | March | Sep | Oct | Nov | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 98 | 99 | 101 | 112 | 119 | 125 | 109 |

| 2 | 11 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 16 |

| 3 | 42 | 29 | 33 | 42 | 38 | 39 | 37.2 |

| 4 | 19 | 12 | 25 | 28 | 21 | 32 | 22.8 |

| Total | 170 | 160 | 169 | 197 | 196 | 218 | 185 |

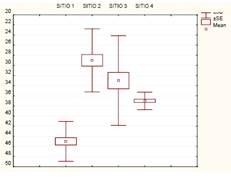

Significant differences were determined when Friedman’s Anova was used to compare populations between sampling sites (N=6, df=3) = 17.00000; p<0.00071, site 1 differing significantly (Figure 2).

As for the time of the year in relation to the observed population, there are no significant differences with Friedman’s Anova (N=4, df=5) = 9.388489 p<0.09454. Likewise, no significant differences were observed when comparing Friedman’s Anova number of animals per site during the study months (N = 4, df = 5) = 9.388489 p <0.09454.

The noise levels measured for each site were on average: 1 = 71.2 dB (50.4-84.5); 2=60.3 dB (44.2-75.2); 3 = 72.1 dB (55.1-85.3) and 4 = 59.6 dB (40.3-68.1).

The determined food sources refer mainly to domestic urban wastes that are deposited in public areas (Table 3). It was observed that this type of resource is not only used by pigeons but also by other species including stray dogs and wild birds: Quiscalus mexicanus (Maria mulata), Pitangus sulphuratus (chamaría) and Campylorhynchus griseus (chupa huevo); As well as rats (Rattus norvegicus) and mice (Mus musculus).

Table 3 Average determination of the daily availability of food present in domestic urban waste deposited in the public area of the study area (Human food surplus - SAH and non-degradable waste - RND).

| Site | SAH (Kg) | RND (Kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | 55 |

| 2 | 29 | 41 |

| 3 | 33 | 62 |

| 4 | 30 | 60 |

| Total | 137 | 218 |

| % | 38.6 | 61.4 |

Friedman’s Anova revealed significant differences in the volume of edible waste per site (N = 30, df = 3) = 64.453, p<0.0001, with site 1 being significantly different from the others (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The average density found in this study, equivalent to 7.71 ind / ha (5.9 to 9 ind / ha), is lower when compared to the two public markets: old and new, from the capital of the department of Sucre, where, respectively, Densities of 200 ind / ha and 57.36 ind / ha 13,14 were found; It is also below the range of 75 to 225 ind / ha determined for the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina 16 and the 9.78 ind / ha found for the city of Barcelona, Spain 25. Notwithstanding this difference in values, a density higher than 4 Ind / ha is considered harmful because it becomes a serious environmental problem 14. It is an invasive species that colonizes urban environments successfully, as it finds sufficient shelter and food in these places, in addition to the relative absence of predators 3,4,26, which allows it to have large population increase, such as those detected in this study and similar work in urban areas of other countries 16,25.

The density differences found among the different sampling sites are given because the environmental conditions of each site are different, and there are also differences in the habitat availability and quality 14,27. It is known that in urban environments, they tend to congregate in flocks that can have hundreds of specimens, which tend to move, fly and perch in groups; They are located in almost all types of urban infrastructure where they can be quiet 3,4 and in areas that offer them the necessary food 3, such as urban human consumption waste, as could be established in This study.

The absence of significant differences between the two seasons of the year, both drought and rainfall, may be due to the fact that there is no reproductive seasonality and their mating, posture and breeding cycles are relatively fast, in total they do not exceed 2.5 months 3; Sexual maturity manifests between 4 and 7 months, being earlier in the male 28; Biological characteristics that partially determine the high population 3,14.

Their diet usually includes seeds, fruits and sometimes invertebrates, when, on the other hand, these pigeons that live in urban environments is based on waste, various grains and other food materials that people give them intentionally or involuntarily 3; In urban areas they have an omnivorous tendency, which is accentuated when it is used as a source of food for garbage collectors 29. In this study they were observed to consume human food waste, which were also harvested by both domestic and wild species, which may represent a serious threat to public health due to their role as host and transmitter of zoonotic diseases 6,30.

The amount of available feed offered by the evaluated wastes, corresponding to an average of 137 kg / day, is comparatively enough, especially considering that the total number of animals estimated was 185 and that a reproductive age adult consumes in Average 70 g / day (25 kg / year) 28.

The food supply and variability of the diet of this bird are categorized under urban conditions as omnivorous 29, allowing to analyze the population abundance by sampling site and the availability of urban food waste in each place, corroborate that the amount of pigeons detected in each site is directly related to the food supply 31, while at the same time it can be cataloged considering its diet as a generalist and opportunistic species; Emphasizing that dietary opportunism is related to optimal foraging theory 32; Which is in line with the search for or use of accessible sources for many kinds of food 33. Additionally, in this case, the urban occupation, the consumption of human food waste and the high population abundance, show a great ecological plasticity 34.

There is the possibility that due to exposure or transport of different pathogens during the search for food or the use of contaminated food, such as those that may be among the household waste of domestic food, which is also shared with other species, including rats and mice, stray dogs and urban wildlife, risk situations are generated for the transmission of diseases in exposed populations 35.

The noise level present in the study area does not disturb the activity of the pigeons, despite being a high noise level. It has been detected that the noise of motor vehicles with values between 80 and 110 decibels does not cause visible reactions in individuals of the mentioned species, which is in line with what is found in this work 16.

The noise levels found in this work, between 50.4 and 84.5 dB, are within the range determined for the New Market of Sincelejo and for the Old Market of the same city, which were: 59.8 and 80.2 Db and 68.2 and 83.5 Db respectively 13,14. The noise level present in the study area does not disturb the activity of pigeons, despite being a high level 13,14,16. It is important to note that the human being is considered to be acoustic discomfort when exposure to sound levels is between 55 and 65dB, and it is established that at 75dB long term hearing loss is observed and between 110-140dB there is hearing loss In the short term and above 140dB, the known pain threshold is presented 36.

To conclude, in urban areas, C. livia domestica can be considered a potential health hazard, not only because of the possible transmission of diseases, but also because of the negative effects it exerts on infrastructure. Especially if the environmental measures necessary to make adequate population control and hygienic management of household food waste are not available.

Considering that C. livia domestica is recognized as a species considered an urban pest, because it transmits various zoonotic diseases, affects infrastructure and contaminates food through its excrement, recording its density, becomes a priority need for public health programs which must be officially implemented.