Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is an infectious zoonotic disease caused by spirochetes of the genus Borrelia, transmitted to humans and animals through the bite of soft ticks (Argasidae) of the genus Ornithodoros1,2. In nature, borreliae are maintained in an enzootic cycle that involves wild mammals (mainly rodents), where ticks acquire spirochetes after short periods of hematophagy (15-90 minutes), remaining chronically infected with the possibility of transmitting microorganisms to new vertebrate individuals, including man, who acts as an accidental host 2.

Around the world, different species of Borrelia are recognized as etiological agents of TBRF, and their epidemiology is directly related to the geographical distribution of their competent vectors 1. According to Cutler 1 the main pathogenic species present in Africa are B. crocidurae and B. duttonii (transmitted by O. sonrai and O. moubata, respectively); in the Mediterranean, B. hispanica (transmitted by the O. erraticus complex); in Asia and Eurasia, B. latyschewii and B. persica (transmitted by O. tartakowskyi and O. tholozani, respectively) and in North America, B. hermsii, B. turicatae and B. parkeri (transmitted by O. hermsi, O. turicata and O. parkeri, respectively).

In Latin America, although there are historical data published during the first half of the 20th century that confirm the presence of human cases of TBRF, its possible etiological agents (B. venezuelensis, B. mazzottii and B. turicatae) and possible related vectors (O. rudis, O. talaje, O. furcosus and O. turicata) in countries such as Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and Guatemala 3-5, there are no recent publications regarding the current epidemiology of the disease.

In Colombia, the first descriptions of the disease date from 1911 and were carried out by Franco et al 6, who described a high fatality outbreak occurred between 1906 and 1907 in a group of workers in Muzo, Cundinamarca, where O. turicata was mistakenly considered (probably confused with O. rudis) as the vector involved 5. Subsequently, during the 20s, Dunn and Pampana 7,8 conducted important studies of ecoepidemiology and clinical aspects of the TBRF, highlighting B. venezuelensis as the probable etiological agent and O. rudis as the main related vector (Figure 1). These ticks predominated in the departments of the Colombian Pacific, where housing in precarious conditions allowed the proliferation of these arthropods and therefore parasitism in humans with the subsequent risk of suffering from the disease, which is characterized by recurrent and paroxysmal febrile episodes, associated with chills, sweating and other nonspecific symptoms, which could easily create confusion with Malaria 4,7,8.

After the bite of an infected tick, an incubation period of seven days happens, there are recurrent febrile episodes (five or more episodes in untreated patients), characterized by paroxysmal fever of 3 to 5 days per episode and a afebrile phase of seven days between episodes 1,2. Pathophysiologically recurrent febrile episodes are explained by the continuous antigenic change in the surface proteins of the borreliae, challenging control by the immune system 1,2. Other frequent and nonspecific symptoms such as headache, myalgias, chills, nausea, arthralgias, vomiting and abdominal pain are usually associated with febrile episodes 2. Complications are infrequent (acute respiratory distress syndrome, meningitis, acute renal failure, hemorrhages) and mortality is less than 5% 1,2. The blood profiles does not present a characteristic pattern, moderate or severe thrombocytopenia is a frequent finding, as is mild elevation of transaminases 2.

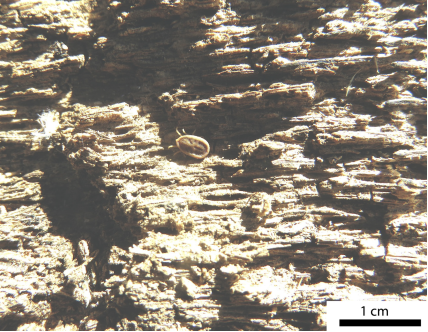

From the diagnostic point of view, the borreliae causing relapsing fever (RF) present a greater bacteremia (>108/ml) with respect to the borreliae of B. burgdorferi sensu lato group (<105/ml) 1,2. Direct detection of the etiological agent can be carried out by molecular techniques (PCR) or by visualization of spirochetes under a dark field or light microscope in peripheral blood smears (performed during febrile episodes) stained with Giemsa or Wright stain (Figure 2). There are also specific antigens present only in borreliae of the RF group, such as GlpQ (glycerophosphodiester-phosphodiesterase), useful for serological diagnosis by ELISA tests 1. This aspect is important considering that the use of other antigens common in the genus Borrelia can trigger serological cross-reactions between borreliae of the RF group and those of the B. burgdorferi s.l group (cause of Lyme borreliosis) 1. The culture of borreliae is usually expensive because it is fastidious and slow-growing microorganisms in culture media BSKII (Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly) and MKP (Modified Kelly-Pettenkofer) 1.

(Source: Álvaro A. Faccini-Martínez, Sebastián Muñoz-Leal).

Figure 2 Borrelia sp. in peripheral blood smear (arrows), Giemsa stain, 1000X magnification

Borreliae of the RF group are susceptible to different antibiotics (doxycycline, erythromycin, penicillin, ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol) and no resistance have been reported 1,2. For the treatment of TBRF, it is recommended to keep the antibiotic therapy for 7 to 10 days. It is important to take into account the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (hypotension, tachycardia, chills, diaphoresis and marked elevation in temperature) as a relatively frequent adverse reaction that occurs in the first 4 hours after the first dose of antibiotic treatment 2.

Taking into account the historical reports of the presence of TBRF in Latin America 3,4, it is very likely that there are currently cases of this disease, predominantly in rural areas of Central and South America, masked by other causes of acute febrile syndrome, highlighting Malaria, given its similar clinical characteristics 4. Therefore, it is important to carry out research studies in order to identify possible circulating Borrelia species, their related vectors, wild hosts and the associated clinical-epidemiological context, which will contribute to the design of prevention strategies in public health.