INTRODUCTION

Brazil, the largest milk producer in Latin America and fifth in the world 1 is facing great challenges to maximize profitability and competitiveness. Mastitis is the disease with the greatest economic impact on dairy farms 2. This disease decreases the income of the farmers in up to 35 billion dollars per year worldwide 3. Losses due to mastitis exceed US $500 million in Brazil 4. Mastitis affects the dairy industry by increasing Somatic Cell Counts (SCC) leading to milk composition variations. It also decreases industrial yields, increases processing costs, changes the organoleptic traits of milk, and reduces the shelf life of dairy by-products 2,5.

Since year 2000 Brazil has been implementing a national program for milk quality improvement (PNQL). The milk quality payment system has sought to stimulate improvements in milk parameters through bonuses and penalties since 2005 6. Incentives include SCC, total bacterial count (TBC) and absence of antibiotics and adulterants 7. Regulatory Instruction 62 of 2011 established limits for SCC and TBC 8, thus from 07/01/2014 until 30/06/2016 reference values were 500 thousand cells/ml for the southeastern region of the country.

Bulk tank SCC levels depend on several factors 5,9, including pathogens, milking system (equipment, facilities and milking routine) and factors related to the animals 10-11. All these factors have been studied in different countries without conclusive results.

Variables related to herd management can help understanding SCC variations in dairy herds worldwide. Those variables include the personality, attitudes, beliefs, values, intentions, skills and knowledge of the herdsmen 12-13. Jansen et al. 12 grouped these factors as “human factor”. Increases in mastitis incidence can be triggered by decreased immunity of the cow, which may be related to sub-optimal farm management.

Behavior theories have established criteria for evaluating the attitudes of the personnel towards specific chores. Ajzen and Fishbein 14, and Ajzen 15 suggested that people with very positive attitudes towards a specific task are more prone to practice it (theory of planned behavior). Jansen et al 12 and Lind et al 16 used these concepts to identify, situational, personal, and cognitive factors to explain why staff performs an action.

The objective of this study was to identify factors associated with bulk tank SCC levels in dairy herds in Southeastern Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location and description of the study area. This study was part of a project by Clínica do Leite ESALQ-USP and DANONE company in 68 dairy herds. SCC levels were below 250.000 cells/mL in 34 herds (BSCC farms), and above 700.000 cells/mL (ASCC farms) in the other group (34 farms). The farms are located in Southeastern Brazil (south of Minas Gerais and north of Sao Paulo state). The climate of the region is subtropical, with 19.25°C annual average temperature, temperate winters and moderately high temperatures during summer. Average annual rainfall is 1.450 mm.

The herds were part of a milk quality program measuring milk composition and sanitary parameters. Most animals were stabled Holstein crosses (63%) and pure Holstein (34%). Average milk yield was 16.02 liters/cow/day. The SCC were performed by Clinica do Leite ESALQ-USP using a Fossomatic ™ equipment.

Face-to-face surveys and checklists were used for assessing milking routines and equipment in order to identify factors associated with the personnel (milkers and producers) and relates them to SCC. Surveys were based on studies conducted by Jansen et al 12 and adapted to Brazilian conditions. Veterinarians, Animal Scientists and agronomists from Clinica do Leite ESALQ-USP and DANONE participated in the study.

Routine checklists and milking equipment. The following activities were evaluated: pre-milking (movement and preparation of animals at milking parlours and waiting corrals, milker apparel, preparation of animals, disinfection of udders, materials used, etc.), milking (milking of animals with mastitis, milking times and routine, operation of the equipment, etc), and post milking (exit of animals, condition of the teats, and condition of the milk filter).

Verification of milking equipment. Checklists based on parameters proposed by Blowey and Edmondson 10 for mastitis control. Criteria related to maintenance frequency, conditions of equipment components (liners, hoses, milk line, vacuum pump, regulators, and pulsators, among others) were used to grade the farms.

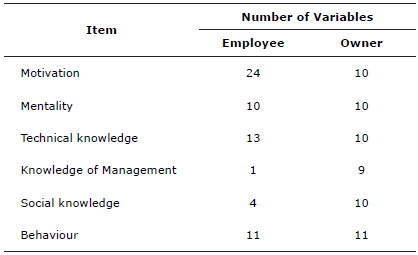

Surveys for employees and farm owners. Surveys included general information (farm name, location, name of owner, general milk quality parameters, number of lactating cows, management of productive information, mastitis control, and herd management, milking system, number of milkings/day, number of milkers, and products used for cleaning and disinfection of the equipment). Two different surveys were used for milkers and owners. The survey structure is presented in table 1.

Table 1 Distribution of variables in the surveys for employees and owners, according to the classification items

The surveys had different number of variables for several items intended for employees and owners: the owner survey for “Motivation” had 10 variables, while the employee survey had 24 (“Motivation” was divided in: Physiological needs, with 3 variables; Sense of belonging, with 4; and Recognition and self-realization, with 11 variables).

The surveys consisted in multiple-choice and Likert-scale responses. At the end, two databases with total values for each item were obtained, one for employees and another for owners.

Behavioral responses. These variables evaluated compliance or not with tasks related to the milking process using the checklist for the milking routine.

Attitude assessment. Milkers and owners were surveyed for milking-related aspects, such as negative or positive, favorable or unfavorable, and improvised or planned attitudes regarding processes, knowledge, motivations and mentality.

Results are presented as percentage scores in which 100% correspond to the “ideal” fulfillment of the items evaluated in each category.

Survey information was handled anonymously, and respondents expressed their informed consent verbally, and in addition they signed an agreement was signed to authorize the entry of project personnel to the farm, and to provide necessary information. The project did not present a risk to the health of participants, and the involvement was voluntary. The collected information was used sorely and exclusively for this investigation, and was not supplied to other persons.

Statistical analysis. A multivariate analysis was conducted, including principal component analysis (PCA) for owners and employees categorized by SCC (ASCC and BSCC) as a qualitative variable. Owner PCA included information from the survey to owners and variables related with checking of milking equipment and materials for the milking process.

The PCA command of FactoMineR library 17 from R-Project 18 was used for the PCA. The Kaiser criterion 19 was used to select factors or components with values greater than 1.

RESULTS

Average milk production (MP) was 1189±1426 L/day, with 121 lactating cows per farm. Daily milk production in BSCC farms was 1276±1749 L/day, and 1102±1027 L/day in ASCC farms. Dairy farms with MP greater than 1000 liters presented average MP per cow of 19.76 L/day, with 572250 SCC/ml in the bulk tank. Farms yielding less than 1000 L/day (64.71%) had 44.4 lactating cows, with 13.97 L/day, and tank SCC levels of 552070 cells/ml.

Analysis of employees. The average age of employees was 36 years for both groups, with 9.30 and 7.11 years of experience in the BSCC and ASCC farms, respectively. The level of basic schooling of employees was higher in the BSCC farms, with 5.60 years versus 4.77 for ASCC farms.

Regarding other variables related to milkers, there was high motivation, identification of positive intrinsic factors, high satisfaction of needs and social contexts, with positive values (higher than 90%) in both BSCC and ASCC farms, indicating that the work environment generates stability that stimulates and motivates milkers to accomplish their tasks.

Variables related to satisfaction of personal and family needs of milkers were greater in BSCC (89.08%) than ASCC farms (88.66%). Variables related to perception of extrinsic factors were higher in ASCC (82.33%) than BSCC farms (79.33%). Attitudes and knowledge about the milking process and mastitis were higher in ASCC (79.63%) than BSCC farms (76.47%). The lowest scores were observed in milking routine checks, with medium level of satisfaction (51.67% for BSCC vs. 46.43% for ASCC farms).

According with the PCA for employees, from the 14 original variables, five components with own values greater than 1 explained 70.82% of the total variability (Table 2).

Table 2 Own values and percentage of variance explained for the components with own values greater than 1, and correlation of variables associated with employees in Brazilian dairy farms.

| Components | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Own value | 3.91 | 1.93 | 1.6 | 1.33 | 1.13 |

| Variance (%) | 28 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 9.52 | 8.11 |

| RCS | 0.21 | -0.06 | -0.05 | -0.70 | 0.52 |

| Age | 0.27 | 0.86 | -0.19 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Schooling | -0.07 | -0.61 | 0.25 | 0.29 | -0.13 |

| Work experience | 0.02 | 0.69 | -0.21 | 0.29 | -0.12 |

| Attitude | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.50 | -0.16 | 0.19 |

| Knowledge | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.66 | -0.27 | -0.14 |

| Self realization | 0.67 | -0.29 | -0.07 | 0.31 | -0.02 |

| Extrinsic Factor | 0.75 | -0.03 | -0.18 | -0.39 | -0.42 |

| Safety | 0.71 | -0.12 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Intrinsic Factor | 0.59 | -0.09 | -0.43 | 0.12 | -0.01 |

| Motivation | 0.81 | -0.05 | -0.26 | -0.32 | -0.38 |

| Needs | 0.88 | -0.16 | 0.097 | 0.31 | 0.22 |

| Routine | 0.25 | 0.226 | 0.63 | 0.10 | -0.43 |

| Social | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| Bold values identify significant variables (p<0.05) for each Principal Component | |||||

The First Component (PC1) for milkers explained 28% of the total variance. It was related with welfare of milkers by grouping satisfaction of needs, motivation, extrinsic factors, sense of security and feeling of self-realization, with 19.95, 16.87, 14.43, 13.00, and 11.52% within each component, respectively, with positive correlations within the component.

The Second Component (PC2) of employees explained 13.8% and grouped age (contributing 38.43% to the component), seniority or experience (24.78%), and level of schooling (19.43%). Time was expressed as age and years of service in the farm, which were positively correlated. Schooling of employees was negatively correlated with this component.

Explaining 11.4%, the employee PC3 included variables associated with staff knowledge and training (27.00%), milking routine (24.94%), and attitude (15.86%), which were negatively correlated with motivation and intrinsic factors (which contributed 4.34% and 11.46%, respectively).

The SCC had the highest influence in PC4, with 36.57%, and PC5 had a high contribution of SCC (23.72%), routine (16.64%), extrinsic factors (15.55%), motivation (12.44%), and social factors (11.02%), which is why both components were strongly associated with SCC levels and milking routine.

Analysis of milking equipment and owner. Both BSCC and ASCC farms had non-satisfactory scores for milking equipment with 67.2 and 65.0% compliance, respectively. The condition and proper maintenance of the equipment were better in BSCC farms (considering teat cups, vacuum and milk short tubes, flow valve, manifold cap, long vacuum and milk hoses, vacuum gauge, and regulator).

The BSCC and ASCC farms scored 89.17 and 80.83%, respectively, for milking routine and materials used during the process (gloves, drying paper, implements for pre and post sealing of teats, implements for mastitis diagnosis and treatment, among others).

The average age of owners in the BSCC and ASCC groups was 52 years, respectively. Variables related to the owner had higher scores in BSCC farms, including behavioral variables, social knowledge, leadership and mentality (scores between 80 and 83%). Scores were between 71.69 and 76.14% for the ASCC farms. Variables related to administration, knowledge about mastitis and dairy production, convictions or principles, and management, scored between 53.4 and 69.21% in BSCC farms, and between 48 and 65% in ASCC farms.

The lowest scores were for variables related to organization and planning (11.75 and 4.4% for BSCC and ASCC farms, respectively).

Three components were identified after the PCA with the information of owners and milking equipment, which explained 63.18% of the variability (40.27, 14.01 and 8.9%) and whose eigenvalues were equal to or greater than one (Table 3).

Table 3 Own values and percentage of variance explained for components with own values greater than 1, and correlation of variables associated with the owner of Brazilian dairy farms.

| Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Own value | 4.83 | 1.67 | 0.97 |

| Variance (%) | 40.28 | 14.00 | 8.90 |

| SCC* | 0.14 | 0.53 | -0.20 |

| Milking equipment | 0.55 | -0.49 | 0.21 |

| Milking materials | 0.67 | -0.12 | -0.04 |

| Administration | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.37 |

| Behaviour | 0.73 | -0.31 | -0.08 |

| Knowledge | 0.73 | 0.34 | -0.11 |

| Social | 0.50 | -0.41 | -0.45 |

| Conviction | 0.48 | -0.44 | 0.32 |

| Leadership | 0.74 | 0.28 | -0.40 |

| Mentality | 0.75 | -0.33 | 0.001 |

| Organization and planning | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.51 |

| Management | 0.87 | 0.39 | -0.04 |

| Bold values identify significant variables (p<0.05) for each Principal Component | *Somatic Cell Count (cells/mL) | ||

The PC1 for owners included all the variables except SCC, with the highest contributions for management (15.62%), assertiveness (11.77%), leadership (11.38%), and behavior (11.09%). The PC2, which explained 40.28 %, could be associated with the administration of the farm.

The variables with the highest contribution to PC2 of owners were SCC (16.95%) followed by condition of milking equipment (14.24%). In this component, BSCC farms were associated to highly assertive owners about production of high quality milk and good condition of milking equipments (maintained and checked according to technical specifications).

The third dimension correlated positively with administration, organization and planning of the farm, and negatively with leadership and knowledge of the social environment.

DISCUSSION

Milk production in southeastern Brazil is based on small farms that provide large amounts of milk for the industry. According to Borges et al 20, only 2.6% of the farms produce more than 1000 L/day, accounting for about 29% of the milk in the region. In the present study, farms producing more than 1000 L/day -corresponding to 35.29% of the herds- are probably suppliers of industrial companies with large storage capacity.

Lind et al 16 related herdsmen age with udder health, which was explained by the age of the personnel and their attitudes towards SCC. In the present study, no difference was observed in the average age of milkers nor in the age of the owners between both farm groups. Accordingly, we suggest to consider age and schooling of milkers in future studies to determine if they have an effect on milk quality in Brazilian herds, since productive and social dynamics of dairy cattle may vary in the country.

Time, which represents knowledge and experience in dairy farms, became a social factor for milkers and owners of dairy herds. This variable influenced behaviors that affect the quality of the process. Not only age of the personnel should be considered as a social and individual factor but also schooling level and work experience, which could favor developing the skills needed to improve udder health and milk quality 12,15.

Despite the perceptions of employees about the workplace, overall job satisfaction, commitment, motivation and availability of milking materials, there are shortcomings regarding the application of knowledge and accomplishment of milking activities. This can be considered as an opportunity for implementing training programs leading to milk quality improvement.

Implementation of good milking practices that helped improve milk quality could have been favored by employees with higher schooling, since milkers from farms with low tank SCC levels had better attitudes and knowledge of the milking process. Higher levels of technical knowledge and schooling favored the implementation of behaviors that improve udder health and milk quality. According to planned behavior theories 15, workers in BSCC farms -which had better scores for motivation, positive intrinsic factors, and satisfaction of needs- presented favorable attitudes towards practices that allow maintaining good udder health and low SCC. In turn, relationships of employees with their social environment, their level of knowledge and access to information could also be favorable for these milkers and influence their intention to develop favorable behaviors.

Employees of BSCC herds should have had positive attitudes and motivations to develop proper behaviors conducing to adequate milking routines ending in quality milk and good health udder. In turn, job stability probably motivated their work. Job motivation has been related to mastitis 13, so factors that motivate farmers to adopt practices that reduce SCC should be identified. This could explain some of the findings in the present study.

Regarding owners, herd management was determinant to differentiate ASCC from BSCC farms, even though compliance values in both groups were low. Good management, which guarantees the supply of resources for adequate milking, was better suited in BSCC farms. Barkema et al 21 compared herd management with milk quality, reporting that herds with low SCC were managed by producers willing to invest in farm resources intended to help achieving their objectives, which in turn favors adequate milking routines. We found that BSCC farmers provided -in greater proportion- the elements necessary for accomplishing proper milking routines. They provided milkers with the proper means to do their job. They also have positive attitudes and behaviors closely related to milk quality. This shows that producers can influence employees to carry out tasks seeking better milk quality and udder health.

In general, the main shortcomings of owners are administrative and managerial tasks, with medium to low scores. Nevertheless, the attitudes of BSCC owners were more positive towards factors that favor reductions of tank SCC. Those factors are leadership and mentality, which translated into behaviors that induced good milking practices. Knowledge and application of good milking routines is crucial for maintaining low tank SCC and colony-forming units (CFU); Calderón and Rodríguez 22 related infectious mastitis levels with dirty udders and bedding material.

Regarding the PCA for owners, the variables that contributed the most were those related with beliefs and behaviors. According to Ajzen’s planned behavior theory 15 they correspond to factors of individual origin related to leadership, management and mentality. Similar results were reported by Barkema et al 21 in a study including 300 Dutch herds. They reported notable differences among producers from low and high SCC herds, finding that lower SCC corresponded to better hygienic conditions and those farms were run by the owners. Those owners worked in the farm, paid more attention to individual cows, and implemented mastitis preventing measures; a strategy included in the herd management.

The low compliance of milking equipments in both groups of farms call for measurement and evaluation strategies to improve udder health and guarantee milking thoroughly and in a short time. Milking equipment generates the greatest dynamic changes, efficiency and satisfaction to the producer 23-24 while is the piece of equipment that works the most hours per year in the herd 25. For this reason, acquisition and maintenance of efficient and functional equipment must obey adequate planning, installation, and operation to guarantee proper milking, care of animals and increase of milk quality. This is important, considering that milking equipment can induce several udder disorders 26, including damage to the teat sphincter, which may decrease milk yield and increase tank SCC and treatment costs.

In conclusion bulk tank SCC levels in southeastern Brazil can be explained by factors associated with the personnel involved in milking. BSCC Farms presented better indicators related to positive attitudes, which generated desirable behaviors that allowed lower SCC.

Implementation of good milking practices should be the basis for improving the sanitary quality of herds, expressed in terms of SCC. Knowledge of the milking process by milkers should improve through training programs favoring the development of positive attitudes and behaviors.

As a conclusion, herd management best explains the variations in SCC for BSCC and ASCC herds, even though total scores were low in both cases. Strengthening herd management would allow owners not only to improve their own behaviors but will also impact milkers to develop positive attitudes towards milking, especially if they are provided with the required elements by the administration.