INTRODUCTION

M. chimachima, regionally known as “pigua”, is a species of the Falconidae family, Falconinae subfamily, and Caracarini tribe with a wide geographic distribution, it is found from the south of Costa Rica through to Colombia, Guyana, and Trinidad, east of Bolivia and Brazil to Paraguay, and north of Argentina and Uruguay, but not in Chile 1,2. In Colombia, it is located throughout the national territory, except in the Department of Nariño. It inhabits areas up to 1,800 masl 3. Cataloged by the IUCN as LC (least concern); in Colombia, it is considered not threatened 4.

Similar sexes have a total length between 400-450 mm; the weight of males is between 277 and 335 g and, for females, is between 307 and 364 g. Phases of coloration: none. Adult: head, neck and lower parts cream-white, crown subtly sprinkled with brown. Brown eye stripe, back and black wings, base of the primaries with black and white points. White upper and lower tail, the latter with fine brown stripes and with a broad subterminal fringe. Black wing tips. Brown iris, yellow periocular area. Blue-pale beak, greenish legs. Juvenile: similar to the adult, brown above and light parts for the adult, brown colored with brown-black 4,5.

It is common in open terrain, often observed on trees, walking on roads and roads or on the banks of bodies of water 3,6. It is also observed in urban areas where it lives and reproduces 7. It is an omnivorous and opportunistic species that can include carrion, live prey and some plants in its diet, including ticks that it extracts from livestock or wild mammals, as well as insects and small fish 3,6. It has been reported as a consumer of corn seeds, tadpoles, frogs, crabs, nesting birds, and even horse dung 4.

This study describes and discusses behaviors that include, nesting, feeding, parental care, learned behaviors, vocalizations and harassment for adult and juvenile individuals. The behaviors observed and discussed here expand the knowledge on the ethology of this species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study zone. The present research was carried out in the dry season, between the months of January and May, 2017 in Santiago de Tolú in the Department of Sucre, (9°31’59” N and 75°34’59” W) (Figure 1), specifically in the southern area of the Colombian Caribbean on the shores of the Gulf of Morrosquillo, an area at sea level that is phytoclimatically classified as a tropical dry forest 8.

Sampling. For the nests, perches and feeding locations within the urban zone, four parallel and synchronized linear transects were applied, running north-south, with an average distance between transects of 300 m and an average length of 1,200 m. Observations were made from 06:00 to 12:00 one day a week in the month of January, 2016 7. Once the birds and their places of activity were located, behavioral observations were carried out using the constant observation method for pre-established periods of time. A fixed counting point 9 was used three times a week between 06:00 and 08:00 and between 16:00 and 18:00, with 4 previously established fixed sighting points (Table 1) using Tasco® 10X70-150 binoculars.

Table 1 Fixed M. chimachima sighting points and the more relevant characteristics.

| Point | Coordinates | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9°31´03´´ N, 75°35´14´´ W. | Sea shore, mouth of the Pechelín River. Zone with mangrove forests. |

| 2 | 9°31´14´´ N, 75°34´39´´ W. | Border area between urban and rural areas. |

| 3 | 9°31´43´´ N, 75°34´47´´ W. Urban area with fruit trees. | Urban area with fruit trees. |

| 4 | 9°32´38´´ N, 75°34´34´´ W. | Mangrove area cut with abundant sand and with domestic waste deposits. |

Information analysis. The data were organized into tables and frequency calculations were made. The ethological analyzes were based on existing, specialized reviews for M. chimachima.

Ethical aspects. The samplings did not include capturing or collecting specimens, but used remote observation, which is why permission from the relevant environmental authority was not required.

RESULTS

Nesting and offspring. Two nests were located: one in point 3 and, in the month of January, 2016, it had two downy chicks. 26 days later in mid-February, the two juvenile individuals started flying with the parents. This nest was located in an isolated coconut palm tree (Cocus nucifera) at an approximate height of 10 meters at the base of a cluster of fruits. The nest materials were dry plants, branches and various leaves. The other nest, detected in February, 2016 in point 1, had a single downy chick. 35 days later in the month of March, this chick was seen flying with the adults. This nest was located in a mangrove tree (Laguncularia racemosa) at an approximate height of 7 meters; its construction included plant material and some pieces of plastic.

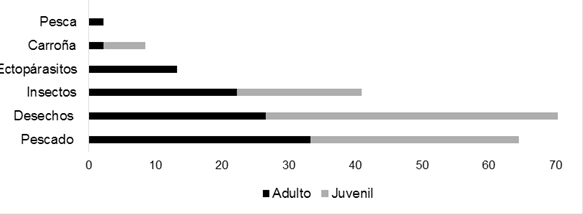

Feeding. Between the months of February and May of 2016, the following were observed for adults for the different points of observation: Point 1. Consumption of fish remains deposited on the beach by tide action was seen 15 times; fishing was recorded on two occasions in an estuary area between the sea and the Pechelín River, in this case an adult was perched on a tall branch next to a juvenile, from there it started a rapid descent and dived into the water up to part of its belly, and extracted a fish that was approximately 10 cm long. Point 2. On six occasions, birds were seen perched on cattle, the consumption of ectoparasites was assumed, and the foraging of insects in cattle pastures was observed 10 times. Point 4. The consumption of fish waste and homemade food was observed 12 times in an open-air garbage dump.

Between April and May, 2016, the following consumption was recorded for juveniles: Point 1. Consumption of dead fish together with the parents was seen five times. Point 2. Following parents in the foraging of insects was observed three times. Point 4. Consumption of domestic organic waste was seen seven times. On the other hand, in the month of April in point 4, two adults and two juveniles were observed consuming the body of a dog. The frequency of consumption observed for each item is shown in Figure 2.

Parental care and learned behaviors. In the two nests with chicks, it was observed that one of the parents always remained vigilant and settled near the nest. Likewise, it was found that the juveniles flew with the adults. In Point 1, it was twice observed that one of the adults took a sand bath then issued vocalizations; later, the juveniles repeated the same behavior, imitating the adult.

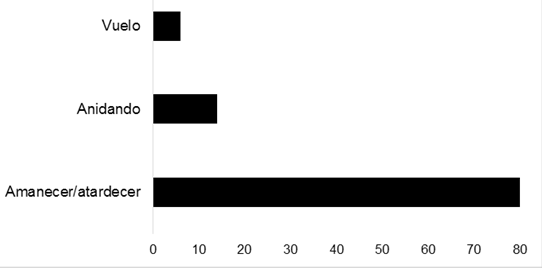

Vocalizations. Three types of vocalizations were detected in the adults: Constant and acute sounds when arriving and leaving the nest were observed on 35 occasions. Vocalizations at sunrise and sunset were heard 200 times while the birds were perched, characterized by a short, high-pitched sound that was repeated. Vocalizations in flight were observed on 15 occasions, identified as a short and high-pitched sound that was not repeated (Figure 3).

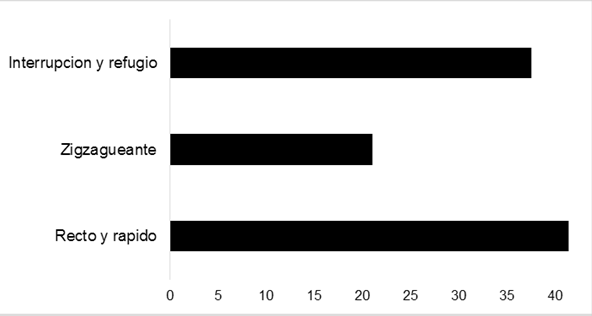

Mobbing. In both Point 3 and Point 4, during the months of February to April, it was observed that adults flying individually were harassed by one or two Pitangus sulfuratus individuals (garrochero or Great Kiskadee) on 181 occasions, chasing the M. chimachima birds, constantly vocalizing and trying to peck them. The flight strategies used by M. chimachima consisted of fast, straight-line flight, zigzag flight and flight interrupted with refuge search. The frequency of flight defense strategies are shown in Figure 4. No mobbing behavior was recorded when the birds flew in a group, nor was aggressive behavior from M. chimachima towards P. sulphuratus observed.

DISCUSSION

The construction of the nest, mainly with plant material, was documented for the species, along with the use of other anthropic materials 4,10. The opportunistic use of human waste materials for the construction of the nest is a valuable option, especially in urban environments where there may be limited natural elements 10. The use of pieces of wood and dry branches is an option that many other species of birds use to build their nests 5,6,10. The location of nests in trees is characteristic for this species 4,7, which also nests in buildings in urban areas 10. The number of chicks was consistent with the established number, one to two eggs 1,4; however, up to four eggs can be reached 10.

In general, the M. chimachima feeding habits reflected that recorded for the species, which is classified as an opportunistic, generalist and scavenger hunter 11. Its diet can include dead and live prey and some plants, including ticks extracted from livestock or wild mammals, insects and small fish 3,6. This species has been reported as a consumer of corn seeds, tadpoles, frogs, crabs, nesting birds, and even horse manure 4.

In this study, the diet was fundamentally represented, in order of importance, by fish, domestic food waste, insects, ectoparasites and carrion, which has been reported in various studies 3,4,6,11 and corresponds to a diet that is adapted to what the urban environment offers. On the other hand, it is known that, among raptors, Neotropical Caracarini hawks are recognized for their foraging versatility 12 and their variable diet 6,13, which was evidenced in this study for the adults and juveniles.

M. chimachima and M. chimango engage in fishing behavior 11,13,14; the observed technique consisted of the location of prey from a perch following by flight and diving into the water, called “perch to water” or “water perch” 13,14. Whereas, M. chimango glides over to the water, “Glide-hover”. However, the technique depends on the availability of perches 13.

It has been reported that, in areas with open beaches without surrounding vegetation, they search for prey with a behavior that is akin to surface fishing or shallow water fishing 13. This does not represent a flight problem for M. chimango or M. chimachima since both species have relatively long tails that allow them to float properly 12; therefore, they can visually locate prey and dive to capture it 13.

Parental care is evident in this monogamous species 1,4, which is manifested by nest care, incubation surveillance and flight of juveniles with parents 14. Juveniles remain with parents for what is assumed to be a learning period 15. The notable learned behavior in this study was taking a sand bath, which consisted of lying on the ground with the legs and wings using sand to clean the feathers, a process of adults teaching juveniles 15. It is also noteworthy that the fishing behavior was only observed in the adults, as was the resting on cattle behavior; it seems that both of these techniques for searching and obtaining food have a learning component, which should be further investigated.

Patterns of information transmission in birds are related to vocalizations 16,17. The song of a bird is used for intraspecific and interspecific communication, which allows the receiver to adjust its behavior. The vocalizations of birds are mainly assigned functions of recognition, territorial defense and reproduction 18. Most vocalizations that are characteristic of M. chimachima are issued at dawn and dusk, and its song is linked to various social and productive human events in the popular culture of the Colombian Caribbean, especially in the Momposina depression 19.

Unlike other birds of prey, M. Chimachima is not fast-flying and is not cataloged as an aerial hunter. The three described types of flights contribute to the knowledge on the biology of this species. Mobbing is recognized as a behavior that seeks to divert a possible predator, is used as a strategy of territorial defense and defends nests and offspring 20-22. Harassment can also be explained as a type of parental care since it is assumed that the offspring of the harasser would be in danger from the predator 23; this hypothesis is based on the fact that the observed displays of harassment coincided with the reproduction of P. sulphuratus3.

In conclusions the results of this study contribute to the knowledge on the behavior of this falconiform species, which has wide occurrence in the Colombian Caribbean, both at the rural and urban levels.

It was determined and reaffirmed that there are behaviors that require learning, including sand baths and fishing, which contributes to the knowledge on parental care.

Mobbing behavior by P. sulphuratus (Aves, Tyrannidae) on M. chimachima (Aves, Falconidae) was recorded for the first time, a strategy that is associated with parental care because these events coincided with the reproductive time of both.