Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural

Print version ISSN 0122-1450

Cuad. Desarro. Rural vol.10 no.spe70 Bogotá Jan. 2013

Sustainability of Rural Development Projects within the Working With People Model: Application to Aymara Women Communities in the Puno Region, Peru*

Sostenibilidad deproyectos de desarrollo rural según el modelo Trabajando con la Gente (Working With People) aplicado en comunidades de mujeres Aimara en la región de Puno, Perú

Durabilité des projets du développement rural selon le modele En travaillant avec les gens (WorkingWithPeople) appliqué dans des communautés de femmes Aimara dans la région de Puno, Pérou

Susana Sastre-Merino**

Xavier Negrillo***

Daniel Hernández-Castellano****

*This article is part of the research project "Developing leadership capacities of women in Aymara communities of Puno (Peru)", developed by the research group GESPLAN Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and funded by the city council of Madrid and the government of Asturias (Spain) in the period 2008-2012.

**PhD student. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros Agrónomos, Departamento de Proyectos y Planificación Rural. E-mail: susana.sastre@upm.es

***PhD student. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros Agrónomos, Departamento de Proyectos y Planificación Rural. E-mail: xavier.negrillo@upm.es

****PhD student. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros Agrónomos, Departamento de Proyectos y Planificación Rural. E-mail: dhdezcastellano@gmail.com

Recibido - Submitted - Reçu: 2012-06-04 • Aceptado - Accepted - Accepté: 2012-06-05 • Evaluado - Evaluated - Évalué: 2012-08-22 • Publicado - Published - Publié: 2013-03-30

Cómo citar este artículo

Sastre-Merino, S., Negrillo, X., & Hernández-Castellano, D. (2013). Sustainability of Rural Development Projects within the Working With People Model: Application to Aymara Women Communities in the Puno Region, Peru. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 10 (70), 219-243.

Abstract

Development projects have changed from a technical and top-down vision to an integrated view pursuing economic, social and environmental sustainability. In this context, planning and management models with bottom-up approaches arise, as the Working With People (WWP) model, that emphasizes on the participation and social learning, also incorporating a holistic approach stemming from its three types of component: ethical-social, technical-entrepreneurial and political-contextual. The model is applied in a rural development project, managed by an Aymara women's organization in Puno, Peru. The WWP model is considered as a useful vehicle for promoting leadership and capacity building in technical, behavioral and contextual project management skills, so that women may become protagonists of their own development, thereby transforming their craft activities into successful and sustainable businesses.

Keywords author: Social learning, competences, Working With People, Aymara communities, development projects.

Keywords plus: Socialization, rural planning, rural development projects, sustainable development, rural development methodology, Aymara Indians, contests.

Resumen

Los proyectos de desarrollo han cambiado desde una visión técnica y descendente a una visión integrada que persigue la sostenibilidad económica, social y ambiental. Surgen entonces modelos de planificación y gestión con enfoques ascendentes como el modelo Working With People (WWP), que enfatiza la participación y el aprendizaje social e incorpora un enfoque holístico de actuación desde sus tres componentes: ético-social, técnico-empresarial y politico-contextual. Este modelo se aplica en un proyecto de desarrollo rural, gestionado desde una organización de mujeres Aymaras de Puno (Perú). El modelo se considera un vehículo útil para fomentar el liderazgo y el desarrollo de capacidades técnicas, de comportamiento y contextuales de gestión de proyectos, para que las mujeres se conviertan en protagonistas de su propio desarrollo, transformando su actividad artesanal en proyectos empresariales exitosos y sostenibles.

Palabras clave autor: Aprendizaje social, competencias, Working With People, comunidades Aymaras, proyectos de desarrollo.

Palabras clave descriptores: Socialización, planificación rural, proyectos de desarrollo rural, desarrollo sostenible, metodología en desarrollo rural, competencias, Aimaras.

Résumé

Les projets de développement ont changé à partir d'une vision technique et descendante à une vision intégrée poursuivant la durabilité économique, sociale et environnementale. Dans ce contexte, apparaissent des modeles de planification et de gestion avec des approches ascendantes comme le modele Working With People (WWP), qui met l'accent sur la participation et l'apprentissage social et integre une approche holistique d'agir à partir de ses trois composantes: éthique-sociale, technique-commercielle et politique-contextuelle. Ce modele est appliqué dans un projet de développement rural, géré par une organisation de femmes Aymara de la région de Puno (Pérou). Le model WWP est considéré comme un moyen d'encourager le leadership et le renforcement des capacités en gestion de projets à caractere non seulement technique, mais aussi personnel et en rapport avec l'évolution du contexte, à fin de que les femmes deviennent protagonistes de leur propre développement, en transformant leur activité artisanale en des entreprises prosperes et durables.

Mots-clés auteur: Apprentissage social, compétences, Working With People, communautés Aymaras, projets de développement.

Mots-clés descripteur: Socialisation, planification rurale, projets de développement rural, développement durable, méthodologie de développement rural, indiens Aymara, concours.

Introduction

The focus of the development projects has been modified over the last quarter of the century (Lusthaus et al, 1999; Horton et al, 2008). In the 1950's and 1960's projects were based on engineering, scientific rationality and top-down approaches (Bond & Hulme, 1999), in accordance with the economic thinking of the time, in which science, technology and planning were infallible instruments for the rational control of nature and society (Llano, 1988). This vision of development was based on the unlimited availability of natural resources (Friedmann, 1991; Enemark & Ahene, 2002), the low wages and ease with which businesses in rural areas were set up, not taking into account the opinions and values of the projects beneficiaries (Cernea, 1991; Llano, 1992), ultimately resulting in numerous conflicts and a lack of integration of projects into the social life of communities.

From 1980 onwards, a progressive change in the paradigm of development can be noted, achieved by including bottom-up approaches by which families and communities were able to gain a central role in managing their resources and projects, ceasing to be the mere beneficiaries of the projects designed from above (World Resources Institute, 2008). Projects with this approach take on a new complexity that require the incorporation of the human aspect and community life (Mosse, 1994). The most renowned early authors that developed such participatory approaches in development and research were Chambers (1983) and Fals-Borda & Rahman (1991) drawing on popular models like those of Freire (1970), as well as Cernea (1991), Korten (1980) and Uphoff (1985). These authors claimed that participatory approaches would empower people and promote more democratic and effective processes.

Their ideas were soon incorporated into the mainstream of development projects, although their practical application has also been periodically criticized for being far from the principles and aims that inspired the approach and for representing a mask to maintain the power distribution (both local power and from external agencies) and control over the decision-making (Kothari & Cooke, 2001). Building upon this critique, participatory approaches have since evolved and are trying to overcome such problems to be able to produce useful alternatives for more successful development processes. Some of the lines of improvement include a multi-scale focus and the involvement of political agents (Hickey and Mohan, 2004).

In addition to these changes in development approaches, the limited nature of resources begins to show, as well as the need to maintain a balance between the strategies for promoting local entrepreneurship and the preservation of resources and lifestyles (Aspen Institute, 1996; WRI, 2008; Berdegué, 2001). This balance is what started to become known as sustainable development (IUCN, UNEP & WWF, 1980; Brundtland, 1988).

Within this context, the need to develop models for planning and managing the development projects based on the capacities of all the stakeholders and the mutual learning that produces their continuous interaction begins to appear. Through this learning process, projects are modified in order to be able to adapt to environmental changes, thereby increasing their sustainability (Negrillo et al, 2010). With this perspective, projects not only contribute to the economic growth but also to the social development of communities, by improving the decisions taken on managing the natural, human and cultural resources, so as to maintain and improve their lifestyle over time (Cheers et al, 2005).

One such model applied to rural areas has been developed under the model named 'Working With People' (WWP) (Cazorla et al, 2010; Cazorla et al, 2011; Cazorla & De los Ríos, 2012). This model has been applied to various different European LEADER projects and also to the case study presented in this article. The latter describes a project for the development of the leadership skills of an association of Aymara women in the region of Puno in the Peruvian highlands. This region is characterized by its extreme poverty, which is linked to very harsh weather conditions that severely limit the development of agriculture and farming. Craftwork appears in this context as an alternative productive activity, developed primarily by women using wool of different qualities and origins, such as alpaca fiber, to make merchandise to be sold at local markets or through intermediaries (Forstner, 2012). Because of the low level of revenue obtained by these means, some women have decided to work together in organizations to improve their market access and sale conditions, receiving support from various NGOs and public entities, with a focus primarily on the weaving technique training (Negrillo et al., 2011, Forstner, 2012). However, in many cases the lack of an integrated business vision has caused a situation in which, once the projects come to an end, many of these organizations are unable to continue with their activities and so the women, due to a lack of capacity building in this sense, return to work in groups, leaving behind the markets gained and reentering to poverty and exclusion. In cases like this, the sustainability of such projects is put into question, as they are evidently unable to generate the necessary change in order to turn a development project into a business entity (Negrillo et al., 2011).

This case study is a response to the situation described, a situation in which groups of women associates are developing skills to turn their craft activity into a successful business project with the aid of counseling from GESPLAN group of the Technical University of Madrid and the NGO "Design for Development" (DPD). The results show the advantages of the WWP model, which strives to give these people the protagonist's role, combining in different ways processes of social learning and skills development for project management throughout the project cycle, in order to identify new ways of developing sustainable projects adapted to local realities.

1. The Working With People model and the development of competences

Working With People (WWP) is a rural development conceptual model defined by Cazorla et al. (2010, 2011) that incorporates the perspective of the participatory approaches, models of planning as social learning (Dunn, 1971; Friedman, 1973) and methodologies of the formulation and evaluation of rural development projects and plans. The model of planning, as social learning, proposes the involvement of people in all stages of the project in a continuous learning process. This learning process is bidirectional, as both the planners and the local people share their expert knowledge and experience (Friedman, 1991, Cazorla et al, 2007). Furthermore, the role that the planners adopt acts as a resource mobilizer and a catalyst of both public and private interests so that innovative solutions in their territories may be found. As a result of this dialogue, every proposal is subject to modification. Therefore action is considered to precede planning. Finally, what has been learnt as a product of the participation of different agents from within society, should condition the future policy-related planning. The emphasis of the WWP model is placed on the contextual and behavioral skills of individuals (International Project Management Association (IPMA), 2009).

The principles that define the model are (Cazorla et al, 2011): (1) Respect and primacy for the people, including their rights, traditions and cultural identity through participatory and integrating processes (Cazorla et al, 2005). (2) To guarantee social well-being and sustainable development. (3) Bottom-up and multidisciplinary approaches reinforcing the abilities and knowledge of the people thereby ensuring the constant development of their territory, and (4) The endogenous and integrated approach.

In addition to these principles, WWP projects can be synthesized around three components, with interactions and overlaps between them through social learning processes.

The ethical-social component: This component is related to the behavior, attitudes and values of people who interact to promote, manage or direct WWP projects. WWP projects are not neutral, but integrate ethics (Habermas, 2004) based on an ideal of service and guided by values (Friedmann, 1993). It is also related to the creation and maintenance of structural, cognitive and relational social capital1 (King, 2004; Nardone et al, 2010; Sherrieb et al, 2010; Uphoff & Wijayaratna, 2000).

The technical-entrepreneurial component: This component integrates the technical elements needed to mobilize resources, generating a flow of goods and services, consulting and negotiating between various actors, assuming and managing risk and translating these resources into a final product that meets the project's goals. These may be both tangible and intangible, like exchanging knowledge or working on social and cultural aspects. This component is related to the development of human capital.

The political-contextual component: This component includes the key elements that allow the project to interact with the context in which it is embedded, including social and political organizations and the public administration. These key elements stem from having an internal organization that facilitates the participation and social involvement, and that is also of use to the people and adaptive to change. This component is related to bridging and linking social capital, referred to the relationships between heterogeneous groups and with people or groups with political or financial power (Narayan, 1999; Sabatini, 2008).

Sustainable development, both in the present and as it should be for future generations, has been taken into account along with the principles and components of the WWP model. Both the ethical-social component (along with its respect for the people, their values and culture) and the political-contextual component (looking at the context of the territory including its natural resources), ensure that the technical investments and efforts be focused on improving the social well-being of the local population in a way that respects the environment and that can be maintained over time.

In order to be able to put this conceptual model into operation, it has been related to the development and use of competences for project management, as part of the learning process that takes place during the project. 'Competence', here, has been defined as "a compendium ofknowledge, personal attitudes, skills and relevant experience necessary to succeed in a particular function" (IPMA, 2009). Among several competency models in the field of rural development projects, we have chosen a holistic model developed by the International Project Management Association because it extends the concept of competence by integrating all the dimensions of people that allow them to conduct a proper professional performance (i.e. behavior, skills, knowledge, motivation, strategic and ethical issues) and classifies competences into three dimensions (Turner, 1996; IPMA, 2009) that can be further linked to the three components:

- The technical dimension. This is related to the abilities and knowledge needed to manage the project successfully. The competences included in this dimension, such as resources, quality, time and phases, costs, communication, etc. are necessary for the good functioning of the technical-entrepreneurial component.

- The contextual dimension. This deals with the stakeholders' interactions within the project context and the permanent organization. This dimension is also related to the political-contextual component taking into account competences like personnel and business management, finances, legal, health, security, safety and environment aspects, among others.

- The beh avioural dimension. This addresses the personal relationships between individuals and groups targeted in a project. It is also associated with the ethical-social component, and involves the use of competences such as leadership, commitment, self-control, creativity, consultation, negotiation, conflict solving, ethics and values.

The WWP model within the perspective of both the social learning approach and the IPMA holistic competence model can be applied in rural development projects as a framework that places the focus on the people involved and promotes their empowerment. The framework could be used at different points of the project cycle to assess the state of the WWP components and competences, to build on the existing strengths and improve the weak elements, to monitor changes and project the effects. Nevertheless, due to the central role given to all the stakeholders that continuously interact and change the project with different proposals and the aim to build capacity in order to enhance the project's sustainability, it is a long process that may not be compatible with short-term projects that seek immediate results. Depending on the context, this process may for

example include previous or on-going work to build or enhance the existing social capital, to have the support of as many people as possible. Time is also needed to reconcile different cultures and points of view, to overcome distrust, to generate teamwork habits and to make decisions. Further research is needed to validate the framework and determine the relationships between elements and the expected outcomes, as these are difficult to measure.

2. Case study context

The structure of the families within the organization is nuclear, with an average of two children per household. 66% of members are married, 26% are unmarried and 8% are widowed. The main source of income within the families is usually the husband's salary, representing 65% of the family income, and the rest come from handicrafts (29%), as agriculture and farming are practiced for subsistence and there is little income associated to them. In 15% of the households, handicraft is the only source of income. The women's average individual income from craft production differs depending on the area, from S./282 in the North to S./108 in the central and southern areas, where contact with tourism is higher.

The aim and lines of action envisaged for the project were set during the initial participatory workshops with an empowerment evaluation tool developed by Fetterman (2000)3. Four workshops were carried out, one with the executive committee and three in each geographic area, with the group leaders. The aim was to increase the technical, contextual and behavioral skills of women entrepreneurs in order to improve their level of independence and allow them to become leaders of the sustainable development of their communities. The lines of action include the fields of textile crafts and agricultural production, alongside a revolving microcredit scheme for funding innovative projects already implemented in other areas of Peru. A SWOT analysis was carried out by GESPLAN and the project was presented to the Council of Madrid (Spain) and was later approved for funding and implementation for a period of two years (pre-investment phase). Other institutions have since provided funding and the project has continued right up until 2012. The development of textile crafts has been the most successful line of action producing several home and fashion textile collections and contributing greatly to the development of related activities (Cazorla et al., 2010).

Figure 1 shows the project cycle and the main action initiatives within each stage. A more detailed description of the project can be found in Negrillo et al. (2011).

3. Methodology

The methodology consisted of analyzing the WWP conceptual components and sustainability dimensions along the project cycle, taking into account the process of social learning that also includes learning and development of competences. Planning as social learning implies a complex process of continuous knowledge exchange between all the stakeholders (Friedman, 1991) that generates innovative solutions and adaptations to changing contexts, hence enhancing sustainability. Both planners and beneficiaries keep an open dialogue not only for planning but also for the rest of the project cycle phases that involves sharing expert knowledge and experience in a way that beneficiaries, by participating actively in the process, also gradually become leaders of the project (Cazorla et al, 2007). In this case, the promoter was the Research Group in Planning and Management of Sustainable Rural Development (GESPLAN) of the Technical University of Madrid (UPM); "Design for Development" NGO acted as a technical expert and the Aymara women Association (CMA) as a local entity that executed the project and that also composed the group of beneficiaries.

The methodology was also based on the principles of sustainable development applied to projects, taking into account economic, social and environmental issues, according to the Brundtland report (1988), as well as the human aspect, placing people at the center of action. Indeed, the dimensions of sustainable development are ultimately conditioned by the human dimension and therefore allow an analysis in terms of people, analyzing the skills required for sustainable development projects (Guerrero, 2011). This multidimensional view of the project exceeds the classical view, which only involves technological disciplines (Trueba & De Cos, 1990). The socio-cultural dimension was analyzed within the social-ethical component and took into account aspects such as organizational structure, as well as respect for the culture and maintenance of identity and values. The technical aspects that were evaluated are related to the incorporation of new techniques and tools through learning processes and the production of new designs. These are analyzed within the technical component. Regarding the economic dimension, the increase of sales and revenues and benefits management were analyzed. Finally, in relation to environmental issues, the use of local resources and the influence that the project may have on them were examined. The latter two dimensions were considered in the analysis of the contextual component. Furthermore, sustainability in terms of intergenerational equity was also analyzed.

To carry out the analysis, we considered secondary information, such as project reports, and primary information collected through qualitative methods such as key informant interviews, participant observation and semi-structured interviews. The data collected aimed at analyzing the skills built among participants in the project as a prerequisite for the effectiveness of the learning process (IPMA, 2009). Based on the IPMA competence model, a questionnaire was designed and applied in semi-structured interviews to a sample that represented 45% of all members of the organization (144 interviews). This sample had a random distribution and was proportional to the number of participants in each group. The sampling error of the variables was less than 9.2%. It consisted of 12 variables and 29 indicators that were selected considering those crucial skills in terms of the context and the objectives of the specific project being worked on, also taking into account that the other competences are related to these, according to IPMA (2009). The variables selected were grouped in accordance with the three areas of competence: (1) technical competences, including project organization, information and communication, teamwork, time and phases, quality and resources; (2) behavioral competences, such as commitment and motivation and creativity; and (3) contextual competences, such as permanent organization, legality, business and finances. The guide was validated together with the group of women from the executive committee of the CMA and was applied to the selected sample. The information obtained was processed, the values of indicators were homogenized through a transformation at a scale of 1 to 4 (1: very low; 2: low; 3: medium; and 4: high) depending on the situation, knowledge and experience about them. The results were then shared through workshops to encourage the learning process, as part of the constant feedback that continuously reorients the project.

4. Results

The results obtained were classified according to the three components that define the WWP model. Globally, the social learning process proposed in the model resulted in a continuous enrichment of the project through dialogue with the affected population. As a result of this dialogue, competences have been improved and strengthened, incorporating innovation and designing new products, marketing strategies, organization and diffusion of the CMA, although the process is very long and still needs external support to continue in the future. In addition, there has been an improvement of an independent source of income for women, who are considered part of the less influential groups in the economic and social life, according to Forstner (2012). This income is usually used to offer their children better opportunities and women are proud to contribute to the household economy. All these aspects contribute to increased project sustainability.

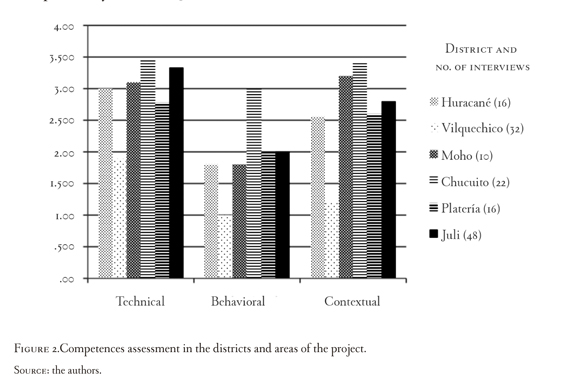

At the level of the assessed competences through the semi-structured interviews, the technical dimension had the highest performance values throughout the territory, followed by contextual and ultimately behavioral dimensions. Results are also related to the spatial distribution of the groups; while the lowest values were observed in the northern districts, due to the remoteness and isolation of the area, the highest values were obtained in the center, that is well connected and with a deep-rooted tradition of craftsmanship and trade (figure 2). Behavioral values were linked to motivation towards and commitment to the project, and values were low because of a low level of knowledge of the project in some areas, that prevented some women from engaging in the activities or because moving to the places where the activities took place was too costly in both time and money.

In fact, the percentage of women who claimed to know the project at the time of the survey (2010) was 16% and 44% in the groups of two of the northern districts and over 60% in the rest of the districts, and similar percentages were obtained in the case of a number of women who participated in project activities. The differences in commitment were seen as a source of conflict for many women. Some of them considered that they had extra work because of a lack of interest from others. On the other hand, the groups that participated less felt that their participation in the project was lower because women that lived close to the main office monopolized the activities and did not inform them. These conflicts have arisen periodically depending on the figure of the elected leaders, who were able (or rather, not) to motivate the whole area, and to keep values such as trust and reciprocity alive within the organization, but sometimes resentment even led to a group to dissociate itself from the CMA. These conflicts have highlighted the importance of leadership, and based on that experience, the actual committee is working to improve the communication system and to include all groups in the activities.

Leadership development has been perceived in terms of the progressive involvement of women in the productive process, especially among the group leaders, as they have asked to learn where to buy the materials, they have travelled to exhibitions, they are looking for training in different agencies and they are getting involved in office work that will allow them to manage the project independently in the long run.

4.1. The ethical-social component

The incorporation of the social-ethical component in planning and project management involves a commitment to values such as participation of women in the economic development of their communities through the promotion of innovation in craft production and leadership development. In this line of action, several results have been achieved so far, first in creating a structure that allows maintaining the values and culture of the Aymara and also in the development of a range of personal or behavioral skills that enables women to manage the project successfully. Both aspects are related to the creation and maintenance of structural, cognitive and relational social capital in the community.

Within the Assembly of the CMA, the first two types of social capital, supported the establishment of internal rules, which were approved and embodied in the statute of the organization. In addition, the organization was legalized with a connected group structure that allows the interaction of many women spread over a large territory who share the same values and have a common vision of the project. These values, culture, vision and mission are reflected in the website of the organization (www.mujeresaymaras.com) as well as in product designs and the organization of meetings, where members still maintain traditions such as sharing food and making offerings to the earth. Since the beginning of the project, this structure has been strengthened and the number of members has increased considerably, from 320 women in 2010 (Negrillo et al, 2010) to a total of 408 women today.

The participation of women in the project has been analyzed at each phase of the project cycle. In the pre-investment phase, the organization leaders were the promoters of the project, so the approach was bottom-up and it had the support of the majority of the members. Participatory workshops with the methodology of Empowerment Evaluation carried out in the three areas were considered useful by women to gain the perspectives of all the groups, who were represented by their leaders. After obtaining a diagnosis of all the activities that women were interested in, there was a great consensus in the prioritization of working on textile handicrafts.

Throughout the management of the project, the decision-making process that the organization had before has remained, starting with a meeting of the executive committee and all the group leaders that report the issues to their groups and, after consulting them, communicate their ideas or decisions back to the executive committee and decide by consensus. Thus, although the groups are organized independently, they are perfectly coordinated to act in an inclusive way, bringing the project to the entire territory in order to take advantage of local knowledge and maximize its potential. In this process, the local technician acts as a facilitator, which has taken some time to be understood by the women who were used to work with top-down approaches. However, this process sometimes involves long periods of time that slow down the progress of the project and the executive committee decides the actions to take. The training activities are organized in a similar way. Training in textile-knitting and design is often offered to one or two women per group that work together for one month and then teach the rest of the group members. In the case of participation in productive activities, the executive committee organizes the distribution of tasks, and conflicts arise as their criteria are not only objective, based on the group's knitting competences, but also on their previous experiences with on-time delivery and with the quality required, and sometimes even based on resentment arising from previous distributions in which some groups were not included.

The evaluation phase has been led by GESPLAN and has consisted of a series of surveys, meetings, workshops, diagnostics, etc. to determine the progress of the work and fulfillment of the proposed objectives. Usually in this phase, members participate as informants and afterwards they receive the results. The information and results obtained form part of a learning process that involves activity modification and reorientation of the project and the proposal of developing new ideas to meet the new needs of the business consolidation in a cyclical and dynamic process (Trueba, 1995).

The participation in the organization is seen by many women as an opportunity to generate an alternative source of income in addition to their other activities. They mainly claim to spend it on improving their children's livelihoods, so they combine their productive and reproductive roles in their households. The executive committee has recognized that gender violence is present in some of the households, but they have also claimed that in other cases husbands are starting to recognize women's work, as they become more familiar with it.

4.2. The technical-entrepreneurial component

Regarding the technical-entrepreneurial component, there have been several activities with the aim of improving the business structure of the organization by mobilizing and managing human and material resources to successfully develop the project action initiatives. The results include the improvement of physical infrastructure, technical skills development and the improvement of the production process. With regard to infrastructure, a place was loaned by the prelature of Juli and adapted, making the necessary changes at the discretion of the beneficiaries and the technical team to meet operational needs. Work, storage, training and quality control areas were created as well as a technical office, and machinery and office equipment was purchased (Negrillo et al, 2011).

To improve the technical competences, specific training courses aimed at members of the organization and training activities for both members and for the technical staff were carried out. A seminar was held on commercial basics for a self-sustaining venture with the participation of businessmen and the president of the National Chamber of Tourism (CANATUR) to further the marketing strategies, enter new domestic and international markets and increase sales of their products. As a result of this seminar, the CMA gained the commitment of a major nationwide commercial gallery to create a permanent display and point of sale for their products. Other specific training courses were organized according to a participatory analysis carried out by the women to detect their weaknesses in production techniques, which again indicates how the learning that emerges from action then goes on to generate new action.

With regard to the training of technical staff both locally and from the UPM, a continuous learning of competences for project management has been favoured and subsequently recognized by the certification obtained via the IPMA scheme. Furthermore, with the support of the Spanish NGO Design for Development (DPD), they are working to improve the quality and innovation of the garments through annual design workshops. In these workshops, the collections are prepared through a process of integration of expert and experienced knowledge to produce designs adapted to international trends and preferences using local production techniques and combining the traditional use of alpaca fiber and cloth with innovative materials. The knowledge gained from the workshop is replicated in different areas across the groups so that all participants may acquire new techniques and skills to step into the production phase of the process. As a result of these workshops, three catalogs of products have been created that are available on the website. Also, a mentality change is taking place, and women are increasingly incorporating new innovation into their own designs.

The production process has been improved through the joint efforts of the staff and women, as a result of the experience gained and the outcome of the competence evaluations, which showed the need to standardize the knowledge and competences in all the geographical areas, to improve communication, time management and quality and to foster teamwork. Both time management and quality are the two aspects that generate the greatest conflict. In the case of time management, although 92% of women reported delivering products on time, in turn they said that they achieved this by working all day and all night prior to delivery and would prefer to know about the work assigned to them further in advance. In terms of quality, only 66% of women claimed to deliver products with the right quality. To improve these aspects, working tools have been adjusted, as well as materials, timing, mechanisms of supply, production, monitoring, quality control and marketing in each group and area. Thus, group members have learned to use the technical data sheets of each item, they have changed the knitting sticks for circular needles, they obtain the highest quality of fabrics, and a reserve for the purchase of supplies has been created. A quality control procedure with nomination of a responsible person per area has also been established and there has been an improvement in marketing methods through internet sales. Furthermore, a local store and several outlets in Indigo Galleries have been opened. In addition, they are working with tourism operators to establish the store as a stopover for tours to enjoy "experiential tourism" where tourists can directly experience the CMA craft activities. Both tourism operators and Indigo Galleries have become stakeholders in the project, contributing their knowledge to the development of the project in a more sustainable way, while also benefiting from the contributions of the women to their businesses.

4.3. The political-contextual component

The results obtained in relation to the political-contextual component are linked to the action initiatives and competences necessary for the development of the organization in the context that surrounds it, mainly through an internal organization that promotes participation and social structuration.

In this vein of the project, progress was made in strengthening the internal organization through various actions, such as the formalization and legal establishment of the CMA and the creation of the executive committee. Additionally, a logo was created as a corporate image of the organization through a competition among women, and it has been included in the presentation and packaging of all garments. The legalization and consolidation of the organization was a slow process, confirming that the development of a social learning process often includes participatory techniques more costly in time and resources, but in turn they are a closer to reality (Cazorla et al, 2007; Negrillo et al, 2011).

As a result of this process, the appreciation of teamwork as collateral to secure quality and improve productivity has also been consolidated and raised, with 84% of women preferring to work in teams. However, the organization still needs to improve structural aspects such as managing and updating the census, since significant differences were observed between the census and the participants, thereby hindering the management of project activities. In all these processes, new communication technologies have acted as the cornerstone, with the use of mobile phones facilitating the internal and external relations of the population.

Regarding the interaction with the context, we analyzed both the relationships of the organization with its ecological environment and with other actors at different scales. In the first case, we looked at the ecological sustainability of the productive activity. The impact on the environment is negligible, as women are knitting alpaca wool that is a local and renewable resource, and they are combining this activity with their traditional subsistence, farming. The use of local resources was one of the prerequisites of the activities proposed by women in the first workshop with the organization. We also analyzed the perspectives of women about the environment and its conservation. 55% of them acknowledged its importance while the rest did not know how to answer. In relation to sustainability in terms of intergenerational equity, the project is based on an activity that mothers teach their children. Through the project, young women are able to knit and gain better technical knowledge than their mothers. They also manage the organization as a business structure and are already gaining management positions.

The organization has established relationships with various local, national and international institutions, in some cases for support and in others to establish business relationships. These include, at a local level, the Rural Education Institute (REI) of Juli, which provides infrastructure support for training activities, and the Prelature of Juli, with the transfer of the premises for the organization's office. Furthermore, the relationship with the Prelature is strong because the organization was originally formed as a pastoral women partnership that linked craft activities with catechesis, social support, health care and combating violence against women. These religious ties maintain very strong cohesion among the members of the organization, providing stability and experience to the institutional structure of the territory. Also at a local level, informal relationships have been established with the town of Juli that are expected to be strengthened in the future. At a national level, they have important relationships with foundations and craft stores to disseminate and present the organization's collections of products. In Spain, UPM acts as promoter of the project and the NGO Design for Development (DPD) provides training in knitting techniques and design collections. They have also established business relationships with associations, entrepreneurs and a major shopping center. Also, through the internet they have established relationships with customers worldwide (Cazorla et al, 2010). These relationships help to bridge gaps and establish ties that ultimately generate a number of benefits associated with access to resources, their accumulation and reproduction for the improvement of local living standards (Piña et al, 2011).

All of these relationships are changing the way the various groups market their products. Before, crafts were marketed in central and southern areas mainly through intermediaries (88% of cases) that sold the products to tourists and through direct sales in the north, where there is no tourism. Intermediaries demanded a certain level of steady production, however, the prices paid by them were very low. In contrast, in the north, direct selling required a lower rate of production, but revenues were higher for each piece produced. Through the project, women are receiving a higher price per hour of work, tripling the previous price. Furthermore, the cost of materials and labor is taken into account - aspects that were not previously considered by them in their calculation of sales prices. This is reflected in the degree of women's satisfaction with the money received, which reached 80%. In addition, this change is especially relevant since the craft is almost in all cases the greatest contribution of women to the household economy. Furthermore, apart from increased labor income, sales have increased from S./21521.50 in 2009 to S./24096.00 in 2010 and finally to S./31340.00 in 2011.

With regard to contextual skills development, allowing interaction with the environment, the skills are related to organizational, legal, business and financial aspects. After the beginning of the project, we observed an increase in business and commercial activity, from 57% of women who sold their crafts as their main source of income before the project began, to 75% with the project in force. There was also some development of financial literacy, reaching 53% of the number of women interviewed interested in borrowing money to finance any activity that improves their productive activity, and 40% intending to start a new business after receiving training. One of the most common businesses is breeding guinea pigs for human consumption. Both this activity and the use of alpaca fiber in craft products favor the use of local resources and small livestock projects that respect the environment.

Moreover, great knowledge has been gained in relation to economic management, both from a revolving fund created as one of the activities of the project and of the benefits generated as a company. The revolving fund was designed jointly by the technical team and the women themselves, adopting a regulation of credit and is currently managed by a credit committee made up of women and is used to finance the purchase of materials. In terms of labor income, this has increased considerably, improving the quality of life of the families in the organization. The management of benefits has been improved, now being distributed among the three zones, which manage them independently, one through a revolving fund, another via a mutual fund and the other by direct distribution among the participants. This also enhances individual activities that invigorate the regional economy. The areas for improvement identified in the analysis include the need for training in economic management of the project as a whole, improving the transparency of the process and reducing imbalances among areas.

Conclusions

The conceptual model "Working With People" contributes to the sustainability of rural development projects because it places people at the heart of the project, who through their participation along the project cycle, modify it to suit their real needs. Based on the planning model as social learning, it advocates a permanent exchange of knowledge, producing continuous learning that will ultimately generate local capacities so that local actors may become leaders in their own development. This development is endogenous, as by defining the project in a particular geographical context, its participants are allowed to interact and take advantage of local resources, creating group links and networks at a territorial level that facilitate access to resources and their utilization.

The competences that are built upon via this process are organized around three components, which, with the aid of balanced development, are able to interact in an integrated manner, thereby achieving sustainability. These components include technical-entrepreneurial, ethical-social and political-contextual aspects, and are related to the development of technical, behavioral and contextual competences, as well as to the social, economic, environmental and human dimensions of sustainable development projects. The integration of these three areas of competence into the analysis of the sustainability of projects is novel and may be useful in the analysis of the development of capacities of all participants through development projects, as they go beyond the traditional approaches focused on technical skills and take into account the specificities given by context (Bond and Hulme, 1999), as well as social and behavioral factors that often determine the success or failure of interventions. This can be accomplished through each of the phases of the project cycle, so that the information obtained in each serves to improve the following, in a continuous learning and feedback process, and the transformation of knowledge into action.

In the case study of Aymara women communities, this approach to planning and implementing the project confirms its utility in enhancing the sustainability of rural development projects. Since projects are changing and vary according to their need to meet the stated objectives, the interaction of the stakeholders improves both planning and its implementation. The methodology behind Working With People and the integration of these figures into decision-making has been valued by the current members of the organization as well as by a significant number of women who desire to become part of it. Moreover, the structure of participation and cohesion has allowed for the overcoming of many obstacles and the maintenance of a common vision, which has favored the progress of the project to increase sales revenue and improve the living standards of the artisans. At a household level, as a third of the members are unmarried or widowed, the increase in income has been recognized as an opportunity to directly improve the livelihood of their children. In the case of married women, some claim to have already started seeing recognition of their work on the part of their husbands, although specific assessment must be carried out to study the gender effects of the project in all households.

Throughout the stages of pre-investment, investment, operation and results analysis, the process of continuous evaluation starting from identifying a certain need, to going on to specify it and achieve its inclusion into the project in a participatory way was forever present. In this process, apart from the incorporation of new participants into the project, as the empowerment of women grows, the role of the technical assistance provided by the UPM is becoming more limited, although they admit that the process is long and much remains to be done in order to be able to comprehensively manage the project independently as a self-sufficient business structure. In that sense, we have identified several areas for improvement related to the three components or areas of competence.

In relation to the social-ethical component and behavioral competences, even if the organization has strengthened the internal structure and women maintain common values, there are some aspects that hinder the development of the project, such as conflict management, which in most cases is caused by envy and resentment between groups and individuals. This can ultimately lead to the failure of the project. This is coupled with differences in the commitment and motivation of different groups, due to the remoteness of certain territories, which has yet to be firmly addressed by the board of directors. As for the technical-entrepreneurial component, progress was made in the design of handicrafts and the incorporation of new information and communication technologies and marketing channels. The main areas for improvement are training in quality issues, time management and communication, both between groups and areas and within groups. Finally, despite advances in the interaction with the context, it is necessary that women continue progressing to develop these skills personally and take ownership of the process, mainly by improving their economic and financial management.

In relation to the above, it may be concluded that the process followed so far must be consolidated by improving the entrepreneurial skills of the members of the CMA, as well as their behavioral competences, to be able to overcome their conflicts and progressively acquire a business-like structure. Sustainability of the activity after the project finishes is highly expected as the groups are developing the necessary behavioral and contextual skills to be able to adapt to changing contexts and to lead processes to identify capacity or marketing programs in the area. Furthermore, they have acknowledged that they should be able to use part of their income to pay for any necessary training.

It is perceived that with this model that promotes an integrated approach to the enhancement of the skills of people throughout all project phases, and through processes of social learning, sustainability is improved in its economic and social components, as it promotes a change of people's mentality from being part of a development project to becoming real agents of a business entity. It is also believed that the local and context based approach accounts for ecological sustainability. Finally, it is also considered necessary to develop more research to validate this conceptual framework and to determine the relationships between components and in turn the relationship between said components and the results expected.

Foot Note

1Structural social capital refers to the rules, established roles, procedures, precedents and social networks that generate social interaction and mutually benefits the collective action by reducing the transaction costs and building social learning. Cognitive social capital is defined as the norms, values, attitudes and beliefs that predispose people towards mutually beneficial collective action (Uphoff and Wijayaratna, 2000; Sherrieb et al., 2010, Nardone, Sisto&Lopolito, 2010). Relational social capital concerns the trust associated with social network relations, which encourages people to work together in order to achieve a common goal and the expectations and obligations of those relationships in the form of reciprocity (King, 2004).

2S./ or PEN is the Peruvian currency. It is equivalent to 0,3769 USD

3This methodology consists of three steps: definition of the mission, taking stock of the activities to fulfill the mission, evaluation of the activities and planning for the future.

References

Arias, A., & Polar, O. (1991). Pueblo aymara: realidad vigente. Cusco: Instituto de Pastoral Andina. [ Links ]

Aspen Institute Rural Economic Policy Program (1996). Measuring community capacity building: A workbook-in-progress for rural communities. Retrieved May 12, 2011 from http://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/measuring-community-capacity-building. [ Links ]

Berdegué Sacristan, J. A. (2001). Cooperating to Compete. Associative Peasant Business Firms in Chile. Wageningen: Thesis Wageningen University. [ Links ]

Bond, R., & Hulme, D. (1999). Process Approaches to Development: Theory and Sri Lankan Practice. World Development, 27 (8), 1339-1358. [ Links ]

Brundtland, G. (1988). Nuestro futuro Común (Informe Brundtland). Comisión Mundial del Medio Ambiente y del Desarrollo. Naciones Unidas. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Cazorla, A., De los Ríos, I., & Díaz-Puente, J. (2005). The Leader community initiative as rural development model: application in the capital region of Spain. Agrociencia, 39 (6), 697-708. [ Links ]

Cazorla, A., De Los Rios, I., & Salvo, M. (2007). Desarrollo rural: Modelos de planificación. Escuela Técnica Superiorde Ingenieros Agrónomos, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Madrid: Ediciones Mundiprensa. [ Links ]

Cazorla, A., De los Ríos, I., Hernández, D., & Yagüe, J. (2010). Working with people: rural development with aymara communities of Peru. International Conference on Agricultural Engineering. France: Clermont-Ferrand. [ Links ]

Cazorla, A, De los Ríos, I, & Yagüe, J. (2011). Trabajando con la gente en los proyectos de desarrollo rural: una conceptualización desde el Aprendizaje Social. In J. Olvera, R. Mendoza, N. Pérez, & I. De los Rios, Modelos para el desarrollo rural con enfoque territorial en México (pp. 9-46). Puebla: Colegio de Postgraduados, UPM, AECID & AltreCosta-Amic. [ Links ]

Cazorla, A. & de los Ríos, I. (2012). Rural Development as "Working With People": a proposal for policy management in public domain. Madrid: Cazorla, A. & De los Ríos, I. Retrieved on March 29, 2012, from http://oa.upm.es/10260/1/WorkingWithPeople_2012.pdf [ Links ]

Cernea, M. (1991). Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development. Oxford: University Press Books. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Cheers, B, Cock, G., Keele, L. H, Kruger, M, & Trigg, H. (2005). Measuring Community Capacity: An Electronic Audit Tool. 2nd Future of Australia's Country Towns Conference. Bendigo. [ Links ]

Dunn, E. S. (1971). Economic and social development: A process of social learning. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. [ Links ]

Enemark, S., & Ahene, R. (2002). Capacity Building in Land Management - Implementing land policy reforms in Malawi. FIG XXII International Congress. Washington, D.C. USA. [ Links ]

Fals-Borda, O. & Rahman, M. (1991). Action & knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research. New York: Apex Press. [ Links ]

Fetterman, D.M. (2000). Foundations of Empowerment Evaluation: Step by Step. Thousand Oaks. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Forstner, K. (2012). Women's group-based work and rural gender relations in the southern Peruvian Andes. Bulletin of Latin American Research. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press. [ Links ]

Friedmann, J. (1973). Retracking America: A theory of transactive planning. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press. [ Links ]

Friedman, J. (1991). La planificación en el ámbito público. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. [ Links ]

Friedmann, J. (1993). Toward and Non-Euclidean Mode of Planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 59 (4), 482-484. [ Links ]

Guerrero, D. (2011). Modelo de aprendizaje y certificación en competencias en la dirección de proyectos de desarrollo sostenible. Tesis doctoral. Madrid: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (2004). The moral and the ethical: A reconsideration of the issue of the priority of the right over the good. In S. Benhabib, & N. F. (Eds.), Pragmatism, critique, judgment (pp. 29-44). Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Hickey, S, & Mohan, G. (Eds.) (2004). Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation? New York: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Horton, D, Alexaki, A, Bennett-Lartey, S, Brice, K. N, Campilan, D, Carden, F, de Souzasilva, J, Duong, L. T., ... Watts, J. (2008). Evaluación del desarrollo de capacidades: Experiencias de organizaciones de investigación y desarrollo alrededor del mundo. Cali, Colombia: Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT). [ Links ]

INEI (2009). Informe Técnico: Evolución de la Pobreza al 2009. Lima: INEI. [ Links ]

International Project Management Association, IPMA (2009), IPMA CompetenceBaseline v.3.1 Valencia: Asociación Española de Ingeniería de Proyectos. [ Links ]

IUCN, UNEP & WWF. (1980). World Conservation Strategy.Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development. Gland: IUCN. [ Links ]

King, N. K. (2004). Social Capital and Nonprofit Leaders.Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 14 (4), 471-486. [ Links ]

Kothari, U. & Cooke, B. (eds.) (2001) Participation: the new tyranny?. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Korten, D. C. (1980). Community organization and rural development: A learning process approach. Public Administration Review. [ Links ]

Llano, A. (1988). La nueva sensibilidad. Madrid: Espasa-Universidad. [ Links ]

Llano, A. (1992). La empresa ante la nueva complejidad. In A. LLano, El Humanismo en la Empresa Madrid: Ediciones Rialp. (págs. 17-32). [ Links ]

Lusthaus, C., Adrien, M. H., & Perstinger, M. (1999). Capacity Development: Definitions, Issues and Implications for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. Universalia Occasional Paper, 35. [ Links ]

Mosse, D. (1994). Authority, Gender and Knowledge: Theoretical Reflections on the Practice of Participatory Rural Appraisal. Development and Change, 25, 497-526. [ Links ]

Narayan, D. (1999). Bonds and Bridges: Social Capital and Poverty. Policy Research Working Paper, 2167. Washington: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Nardone, G., Sisto, R., & Lopolito, A. (2010). Social Capital in the LEADER Initiative: a methodological approach. Journal of Rural Studies, 26, 63-72. [ Links ]

Negrillo, X., Yagüe, J. L., García, A., & Montes, A. (2010). Aprendizaje social en los proyectos de desarrollo: El caso de la Coordinadora de Mujeres Aymaras en Juli (Puno, Perú). Selected proceedings from the 14th International Congress on Project engineering. Madrid, Spain. [ Links ]

Negrillo, X., Yagüe, J. L., Hernández, D., Sagua, N. (2011). El Aprendizaje social como modelo de planificación y gestión de proyectos de desarrollo: La Coordinadora de Mujeres Aymaras. 15th International Congress on Project engineering. Huesca. [ Links ]

Oliart, P. (2008). Indigenous Women's Organizations and the Political Discourses of Indigenous Rights and Gender Equity in Peru. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 3 (3), 291-308. [ Links ]

Piña, H., Castellanos, J., Morales, A. (2011). Capital social en la cadena aloe, estado Falcón, Venezuela. Cuadernos de desarrollo rural 8 (66), 103-122. [ Links ]

Sabatini, F. (2008). Social capital as social networks: a new framework for measurement and an empirical analysis of its determinants and consequences. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38, 429-442. [ Links ]

SENAMHI (2009). Reporte anual del clima por regiones. Perú: Edición regional del Servicio Nacional de Metereología e Hidrografía. [ Links ]

Sherrieb, K., Norris, F. H., & Galea, S. (2010). Measuring Capacities for Community Resilience. Social Indicators Research, 99, 227-247. [ Links ]

Trueba, I., & De Cos, M. (1990). Definición de Proyectos de Ingeniería. VI Congreso Nacional de Proyectos de Ingeniería. Almagro, Spain. [ Links ]

Trueba, I., Cazorla, A., & De Gracia, J. (1995). Proyectos Empresariales: Formulación, Evaluación. Madrid, Barcelona, México: Mundi Prensa. [ Links ]

Turner, J. (1996). International Project Management Association global qualification, certification and accreditation. International Journal of Project Management, 14 (1), 1-6. [ Links ]

Uphoff, N. (1985). Fitting Projects to People. In Cernea, Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development (p. 13-57). Oxford: Oxford University. [ Links ]

Uphoff, N., &Wijayaratna, C. M. (2000). Demonstrated Benefits from Social Capital: The Productivity of Farmer Organizations in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. World Development, 28, 1875-1890. [ Links ]

World Resources Institute (WRI) in collaboration with United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Environment Programme, and World Bank. (2008). World Resources 2008: Roots of Resilience - Growing the Wealth of the Poor. Washington, DC: WRI. [ Links ]