Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural

Print version ISSN 0122-1450

Cuad. Desarro. Rural vol.11 no.74 Bogotá July/Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.CRD11-74.tsgq

Towards a "2nd Generation" of Quality Labels: a Proposal for the Evaluation of Territorial Quality Marks

Hacia una "2" generación" de sellos de calidad: una propuesta para la evaluación de las marcas de calidad territorial

Vers une «2ème génération» de labels de qualité: une proposition pour l'évaluation des marques de qualité territoriale

Eduardo Ramos*

Dolores Garrido**

*Doctor de la Universidad de Córdoba (España). Ingeniero Agrónomo, Especialidad Economía Agraria, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (España). Email: eduardo.ramos@uco.es

**Doctora de la Universidad de Córdoba (España). MSc en Desarrollo Rural, Universidad de Córdoba (España). BSc (Hons) in Environmental Management-Cesmas (España)-University of Wales (Reino Unido). Email: dolores.garrido@uco.es

Recibido: 2013-12-13 Aprobado: 2014-05-08 Disponible en línea: 2014-07-27

Cómo citar este artículo

Ramos, E. y Garrido, D. (2014). Towards a "2nd Generation" of Quality Labels: a Proposal for the Evaluation of Territorial Quality Marks. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 7/(74), 101-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.CRD11-74.tsgq

Abstract

Recent literature analyses the role of territorial specificities, as the core of territorial rural development strategies based on differentiation. Unfortunately, the proliferation of quality assurance schemes is provoking a "labyrinth of labels" which diffuses the local efforts for capitalizing rural specificities. A second-generation of labels is currently being developed to simplify the territorial differentiation message. A number of territories in Southern Europe are basing their rural development strategies joining the so-called European Territorial Quality Mark (ETQM) Project. This paper proposes an original methodology, designed and developed by authors, for the evaluation of some of these second-generation labels. This methodology has been validated in 15 rural territories as the pioneers of the ETQM in Spain.

Keywords: rural development; specificity; territorial differentiation; label; territorial quality mark; evaluation; methodology

Resumen

La literatura reciente analiza el papel de las especificidades territoriales como el núcleo de las estrategias de desarrollo territorial rural basadas en la diferenciación. Desafortunadamente, la proliferación de los sistemas de garantía de calidad está provocando un "laberinto de sellos", que difunden los esfuerzos locales de capitalizar las especificidades rurales. Una segunda generación de sellos se está desarrollando actualmente para simplificar la diferenciación territorial. Una parte de los territorios al sur de Europa está basando sus estrategias de desarrollo rural mediante el proyecto Marca de Calidad Territorial Europea (MCTE). Este trabajo propone una metodología original, diseñada y desarrollada por los autores para la evaluación de algunos de los sellos de segunda generación. Esta metodología se ha validado en quince territorios rurales como los pioneros de la MCTE en España.

Palabras clave: desarrollo rural; especificidad; diferenciación territorial; etiqueta; marca de calidad territorial; evaluación; metodología

Résumé

La documentation récente analyse le rôle des spécificités territoriales comme le centre des stratégies de développement territorial rural fondé sur la différenciation. Malheureusement, la prolifération des systèmes d'assurance de qualité est en train de provoquer un « labyrinthe de labels », qui répandent les efforts locaux pour capitaliser les spécificités rurales. Une 2eme génération de labels est en train d'être développée pour simplifier la différenciation territoriale. Une partie des territoires au sud de l'Europe fonde leurs stratégies de développement rural en faisant partie du projet « Marque de qualité territorial européen » (MQTE). Ce travail propose une méthodologie originale, dessinée et développée par les auteurs, en vue de l'évaluation de quelques labels de deuxieme génération. Cette méthodologie a été validée dans quinze (15) territoires ruraux qui sont les pionniers de la MQTE en Espagne.

Mots-clés: développement rural; spécificité; différenciation territoriale; label; marque de qualité territoriale; évaluation; méthodologie

Introduction

Two types of problems threaten the future of rural territories: those related to globalization (a purely competitive logic), and those arising from the growing competition between labels (a logic of differentiation based on quality). However, both problems offer opportunities for territories that know how to exploit them to their advantage.

First, the agricultural crisis and the advance of economic globalization1 have led to the decline of many rural territories in Europe over the last two decades. However, the exploitation of local specificities linked to identity offers interesting opportunities for territories to differentiate their products in contrast to the productivist logic imposed by global commodity markets. In addition, rural territories can enhance their competitiveness strategies through pluriactivity and diversification by carrying out new functions which are closely related to the preservation of heritage and the environment, as well as the provision of other public goods (Segrelles, 2000). However, the competitiveness of the territories will also depend on their ability to ensure that common assets are used in a sustainable way (European Commission, 2008a).

Secondly, the challenges facing today's society have led to changes in demand based on values associated with sustainability. These changes explain why some consumer groups are willing to pay a premium for products embedded with specific territorial values (Vandecandelare, Arfini, Belletti & Marescotti, 2010). In this vein, some differentiation strategies seek to lend products a social meaning in addition to tangible specificities in order to create a link between consumers and the geographical origin of the products (Renard, 1999). Thus, differentiated products linked to territorial specificities are a potential source of competitive advantage. But this potential will only have strategic value if it serves to generate rents of specificity (Ulloa & Gil, 2008). For this reason, niche markets based on specific products provide important opportunities for creating jobs, strengthening the business fabric and reinforcing social cohesion (Ilbery & Kneafsey, 2000).

The potential of short circuits to exploit specificities through no-labeling strategies has been and is widely used, but with limited success. For this reason, labeling strategies have been developed for decades. These strategies are based on distinctive labels or marks whose primary aim is to guarantee the differential characteristics of a product or its production process. The greatest potential for labeling strategies is based on two factors: a) the market area ("lengthening" the radius of the local market); and b) consumer trust and loyalty (deeper and of a larger number of people). But for both factors to operate in the same direction and achieve the objective sought by labels or marks, a rigorous and reliable certification scheme is essential and, where appropriate, the adequate traceability of each type of product.

Using marks or labels that make explicit reference to product origin have long been in place in the EU. Labeling strategies can be grouped into two philosophies: a) those directed at certifying processes (very widespread and supported in continental countries that are more in favor of economic liberalization); and b) those aimed at guaranteeing the specific characteristics of the products, which derive from the place where they are produced (located primarily in Mediterranean countries) (Ilbery & Kneafsey, 1998; Henchion & McIntyre, 2000). In the beginning, the differentiation strategy was launched to defend the interests of producers and guarantee quality with a view to consumers. In some countries, the strategy has been so successful that quality labels of this type have been very diverse and used on a wide range of products.

Consistent with the above, and to move towards the objective of territorial cohesion as set out in the corresponding Green Paper (European Commission, 2008a), European Union institutions increasingly emphasize the need to rebuild the links between urban and rural areas. According to this perspective, strategies for territorial differentiation are one way to strengthen such linkages. Consequently, the logic of quality has been recently reinforced with the approval of the so-called Quality Package (European Commission, 2010; 2009; 2008b) to increase opportunities for territorial development through differentiation linked to origin.

However, the enormous proliferation of labels in countries using this strategy is divesting them of, if not neutralizing, many of the outcomes th ey seek. In this regard, two problems have arisen: a) the greater the effort2 that is made to improve the impact of such labels, the greater the entropy3 in quality systems linked to geographical origin; b) due to the growing number of labels (which guarantee differences), it has become increasingly difficult to identify the differences between specificities. To a large extent, both problems have contributed to reducing the effectiveness of differentiation strategies due to what is known in economics as diminishing or negative marginal product. The weaknesses caused by these problems (European Court of Auditors, 2011) is used by opponents of differentiation policies to question their future, with the argument that such policies distort the international food and agriculture products market (Josling, 2006).

Given these problems, it is reasonable to ask the following question: Is it feasible today to enhance the impact of quality labels linked to geographical origin that are based on territorial specificities?

To answer this question, some rural territories have been working for years to implement territory-specific labels and quality assurance schemes as a strategy for territorial rural development. By launching these "second generation" labels, the territories aim to capitalize on their specificities by taking advantage of the opportunities offered by globalization and the new common policies of the European Union.

These second generation labels (territorial quality marks) are a relatively new strategy and have therefore not always sufficiently developed the necessary mechanisms and protocols to ensure that they are effective. The relevance of this insufficient instrumental development stems from the fact that it is indispensable to establish and strengthen linkages within the territory on the one hand, and between the territory and consumers and users on the other. In this regard, the European Territorial Quality Mark Association (ETQMA) has commissioned the University of Cordoba to carry out a series of research projects with the support of the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture (MARM). These projects have, among others, the following three objectives: a) to identify and characterize instrumental deficiencies in the ETQM network; b) design and develop tools to consolidate the ETQM territorial mark; and c) analyze the viability of second generation label strategies in different scenarios.

In line with the above, the aim of this paper is to present the key elements of an ad-hoc methodology to evaluate territorial quality marks, which was obtained as a preliminary result of the ongoing research line mentioned above.

To achieve this goal, this paper addresses the following issues: a) the complexity and implications of the profusion of differentiated labels linked to geographical origin; b) the presentation of territorial or second generation labels based on strong linkages between the label and the rural development process of the territory; and c) the presentation of an original methodology specifically developed to evaluate territorial marks.

1. First generation labels: a labyrinth of labels

Some rural territories in Europe are trying to capitalize on their specificities by developing labels and quality assurance schemes. This strategy aims to add value to local production systems due to their high potential for such value (Becker & Staus, 2008; Marescotti, 2003; European Commission, 2000). While different schemes have been implemented for this purpose in the food and agriculture sector, those based on linkages between the product and geographical origin are the most common.

The designation of food and agriculture products according to their origin has traditionally served to differentiate quality in the food industry. Since the adoption of the Lisbon Agreement in 1958, major advances have been made to protect and regulate the differentiation of geographical indications. Since 1992, and following the publication of various regulations, the European Union has undertaken to protect and regulate the differentiation of its agricultural products through two instruments: a) the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO); and b) the Protected Geographical Indication (PGI).

In the European Union, there are currently three registers of food and agriculture products4: the register of agricultural farm products and foodstuffs; the wine register, and the spirits register. Together, the three registers now list over 3000 geographical indications (including both PDOs and PGIs). Of this total number, most indications are concentrated in southern European countries, with Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and Greece (in this order) accounting for more than 75%.

Products with no mention of origin (standard quality) must comply only with technical and health regulations concerning food processing and good agricultural practices. On the other hand, products bearing origin-linked quality labels (what we propose calling first generation labels) offer consumers added value over the standard quality.

In recent years, and parallel to the implementation of these official labels, other unofficial labels that make reference to the geographical origin of the product (not only for agricultural and foodstuffs) have also appeared on the market. These labels have been developed as a manner of self-identification, recognition, as an administrative type of promotion, or to certify a particular process (Trognon & Delahaye, 2011).

The excessive proliferation of quality labels linked to the territory of origin only serves to compound consumer confusion. Indeed, these labels are producing the opposite effect to that sought by quality labels, particularly given the current economic crisis. For this reason, we refer to today's scenario as a labyrinth of labels and ask: Why are there so many differences? And: How can we "differentiate" the differences?

Following Frayssignes (2011), this situation increases the risk of trivializing labels due to the "information overload" caused by overlapping marks. Furthermore, from the point of view of a territorial strategy, this is an inherent weakness due to the increasing number of non-binding initiatives and the absence of strategic, "bottom-up" thinking that often translates into a lack of territorial coherence. On the other hand, there is a relative lack of tools to assess the impact these labels have on the territories.

This labyrinth is a problem of concern to both administrations and stakeholders. For this reason, certain sectors are calling for the need to simplify, clarify and redirect strategies aimed at the differentiation of specificities. With the publication of the Green Paper on agricultural product quality in 2008, the European Commission launched a process of reflection and consultation on how to ensure the most suitable policy and regulatory framework to protect and promote the quality of these products (European Commission, 2008b)5. As the document states, "the EU farmers' most potent weapon is 'quality" for determining whether the existing instruments could be improved and to decide what new initiatives could be taken.

As a result of this process, in 2010 the Commission launched the Quality Package (European Commission, 2010); the first step towards a comprehensive product quality policy that includes the following proposals: a) a new agricultural product quality schemes regulation; b) a new general base-line marketing standard; and 3) new guidelines of best practices on voluntary certification schemes. In the same direction, the European Court of Auditors (2011) has raised the following question: "Do the design and management of the geographical indications scheme allow it to be effective?". This special report concludes that it is necessary to clarify the control system related to geographical indications and that a clear strategy is lacking on the issue of awareness among both producers and consumers.

In a parallel manner, and in line with the issues raised by the above EU institutions, some rural territories are trying out innovative approaches to simplify the labyrinth of labels by designing and launching umbrella marks (those the authors call second generation labels) as discussed in the following section.

2. Second-generation labels: territorial umbrella marks

Some rural areas are launching second-generation labels to simplify the message and reduce the hypertrophy of the quality differentiation system linked to origin. These labels are intended to preserve both the identity and the cultural, social and environmental resources of these territories with a view to their development (Lorenzini, 2011). Due to their contribution to territorial rural development, the most important of these labels are those that pursue Territorial Quality. For the purposes of the research line of which this paper forms part, Territorial Quality has the following dimensions: a) the quality of the goods and services of the territory (based on their differentiation and mode of production following social, environmental and economic criteria); b) environmental quality (sustainable resource management and the conservation of landscapes and ecosystems as factors of competitiveness); c) social and institutional quality (local institutional actors committed to the process who engage in effective management) in order to achieve; d) quality of life of the inhabitants of the territory (employment, income, healthy environment and social cohesion, with access to public services and services to meet basic needs); in a geographical area with a strong identity and sense of social responsibility belonging (preservation and promotion of tangible and intangible heritage).

The aim of a Territorial Quality scheme is to make the strategy visual through a label that can guarantee consumers (both in and outside the territory) the tangible and intangible quality dimensions of the goods, services, natural and cultural heritage and institutional elements that the rural territory offers.

The most important features of this new generation of labels include: Y Territorial approach: The label as an umbrella mark that identifies those products of the territory (not only foodstuffs) contributing to the quality of the territory as a whole. For these marks, the territory itself is the product (Ramos, 2008), where territory is understood as a result of consensus reached among local stakeholders. This bottom-up process arises in response to the challenges of globalization and is a consequence of the social capital and trust between local stakeholders (Putnam, 1993). For this reason, it may be said that the territory thus understood is a social construct (Pecqueur, 2005).

- The combination of tangible quality attributes (equal to or greater than those expressed with first generation labels) and the added bonus of territorial development (through intangible attributes closely linked to the development process). These intangible attributes are closely linked with the new demands that today's society is making of rural areas in response to the challenges facing the European Union and which are driving change in public policy regarding public goods (Belletti, Marescotti & Moruzzo, 2003). When products (be it a good or service) carry the territorial quality mark they send the message to potential consumers or users that their mode of production is contributing to achieving the development goals that have been agreed upon socially for that territory (to a large extent, these intangible values are related to territorial social responsibility).

- Construction through processes of action and collective intelligence. These processes contribute to the creation and preservation of territorial assets6 through the formation of a broad and representative network of territorial stakeholders.

- Creation and strengthening of rural-urban linkages, which are essential for the development of agricultural and non-agricultural activities. Through such linkages, a relationship is established with demand outside the territory. This relationship has a decisive influence on the viability of most initiatives as it permits greater access to resources, know-how, networks and relationships that are external to the rural world.

- Innovation is viewed as a way to increase the productivity of the territory in three directions: a) processes: by transforming factors into products (goods or services) more efficiently; b) products: by substituting certain products for others with higher value added and/or more elastic and dynamic demand; and c) management: in terms of both how production units are organized and improving market relations.

- Competitiveness is based on institutional development as a way of capitalizing on the opportunities of globalization.

- Two-way communication between producers and consumers (in and outside the territory) and the standardization of the quality message by simplifying the system and facilitating the identification and understanding of differential attributes.

Through its convening power, a territorial mark is likely to create a space for dialogue between stakeholders, which helps break down barriers between different sectors and territorial actors (Frayssignes, 2011). Y Cooperation as a key element. The territorial mark does not compete with other ones linked to origin (i.e. PDO, PGI), labels or quality assurance schemes (i.e. ISO), but reinforces their effectiveness by creating synergies.

3. Methodological proposal for the evaluation of territorial marks

The development of a territorial quality mark, like any other type of mark that embeds intangible attributes, is conditioned by the ability to engage in a contract based on trust (Sylvander, 1995) with consumers to secure and increase their loyalty. The growth and depth of this trust depends on the ability of the mark to explain and disseminate the tangible and intangible attributes of the products that bear the mark, and on the assurance and confidence that the evaluation and certification scheme inspires. Accordingly, this requires designing and implementing a rigorous and objective methodology to achieve this aim on the one hand, and combining and taking into account the different dimensions of territorial rural development processes on the other.

In the last two decades, numerous works have been published on the need to evaluate the effects of spending programs in the European Union in general (European Commission, 1996; 1999), and on the Leader Program and/or territorial specificities in particular (European Commission, 2002; Marangoni, 2000; Midmore, 1998; European LEADER Observatory, 2000; Thirion, 2000). In line with this trend, many assessment reports have focused on rural development programs, as well as some experiences in the self-evaluation of the strategies of some territories. The common factor of all of these reports is that they analyze the effectiveness of spending, and give much less importance to the effects. However, a broadly accepted methodology has not yet been developed to analyze the coherency and rigor of the territorial quality marks, or on the impact these marks have on the territories in which they are implemented.

Regarding this problem, the European Territorial Quality Mark Project (ETQMP) represents an exceptional observatory and laboratory to tackle this lack of effective evaluation methodologies. It emerged as a transnational cooperation project launched by three rural territories (Spain-France-Italy) under the European Community Initiative LEADER7, in 1999. Ten years later, it involved a large number of partner territories: 44 in Spain, 5 in Greece, 1 in Italy, and 1 in France. Hungary and Portugal also started the process of setting up a national network to implement the project. Taking into account only the thirty one Spanish territories that have currently finished the initial arrangements to implement the strategy, the project covers more than 900 municipalities with a population of over 1 million inhabitants spanning an area of over 50 000 km2, and involving more than 400 firms and other rural entities.

The ETQMP pursues two complementary objectives by using two types of marks (logos):

- Territorial level: To increase the competitiveness of each territory based on criteria of quality, environmental conservation and social responsibility, by creating a series of specific territorial marks, one of them for every partner territory. Each of these marks operates as a specific mark (territorial logo) for all the goods and services (foodstuff, touristic services, heritage) that fulfill the requirements for quality of the territory; this strategy is supposed to simplify the consumers' choice.

- EU Network level: To promote the territories involved in the project by means of a European common label (Rural Quality® logo) to facilitate and encourage the commercialization of their products in dynamic markets. At the same time, this umbrella mark also contributes to simplify the quality message sent to consumers: "products under this mark have been produced in rural territories sharing common social responsibility values". In other words, consumers who buy these Rural Quality® products not only are buying a good product but contributing to the sustainable development of those rural territories.

According to these two complementary objectives, the marks evaluation protocol included in the ETQMP distinguishes the following two levels: a) Territorial level: the certification of both companies and products, meaning that they fulfill the local requirements for territorial quality, and authorizing them to use the specific territorial mark; b) EU Network level: the territory accreditation, meaning that they fulfill the ETQMA requirements for territorial quality, and authorizing them to use the common Rural Quality® mark together with their specific territorial mark.

The methodology proposed here deals only with the accreditation evaluation (EU Network level), being the certification evaluation (Territorial level) out of the scope of this paper8. In addition, this methodology intends to become a suitable tool to evaluate, in terms of excellence, the contribution of territorial mark strategies to the sustainable development of the (rural) territories where they are implemented.

3.1. Methodological challenges

The lack of a methodological precedent, and the need arising from a real project that is currently underway (the European Territorial Quality Mark -ETQM- Project), justify the design and implementation of an ad-hoc methodology that combines the needs of an actual project and the rigor of academic research.

The first challenge in developing the methodology stems from the complexity of transforming an abstract idea, Territorial Quality, into a realistic set of indicators. This difficulty arises because the methodology must be able to ensure consumers that the values, feelings or images evoked by a territorial mark are the results of the dynamics of development in which they have been obtained. Yet doing this in a simple, intelligible and rigorous manner is not an easy task.

The challenges listed below are related to the actual design of the methodological tool. The heterogeneity of the circumstances that converge in rural development processes has made it necessary to develop a multidimensional evaluation scheme that also takes into account the following questions:

- Tangible and intangible attributes: Rural territories perform both market-driven production functions and other functions that generate public goods (multifunctional approach).

- Quantitative Criteria vs. Qualitative Criteria: A territorial quality mark as a strategy for sustainable development involves economic, social, institutional and environmental factors that cannot be separated from one another. Therefore, it is necessary to use quantitative and qualitative variables that must be integrated and harmonized.

- Objective Assessments and Subjective Assessments: The coexistence of quantitative and qualitative variables implies the need for a mechanism of objectification and the inclusion of a procedure to verify the evidence, as well as the objectification and standardization of the value of the proposed indicators.

- Diversity of sectors and actors: This requires using different tools for collecting information and calculating the value of the corresponding variables.

- Territorial diversity: This involves different types and levels of institutions, which requires flexibility in applying the methodology based on a single protocol.

The methodological proposal presented here in a summarized manner is based on three original and innovative elements in terms of coherence and actual applications: a) the structure; b) the application protocol; and c) the process of analyzing the results.

3.2. Structure

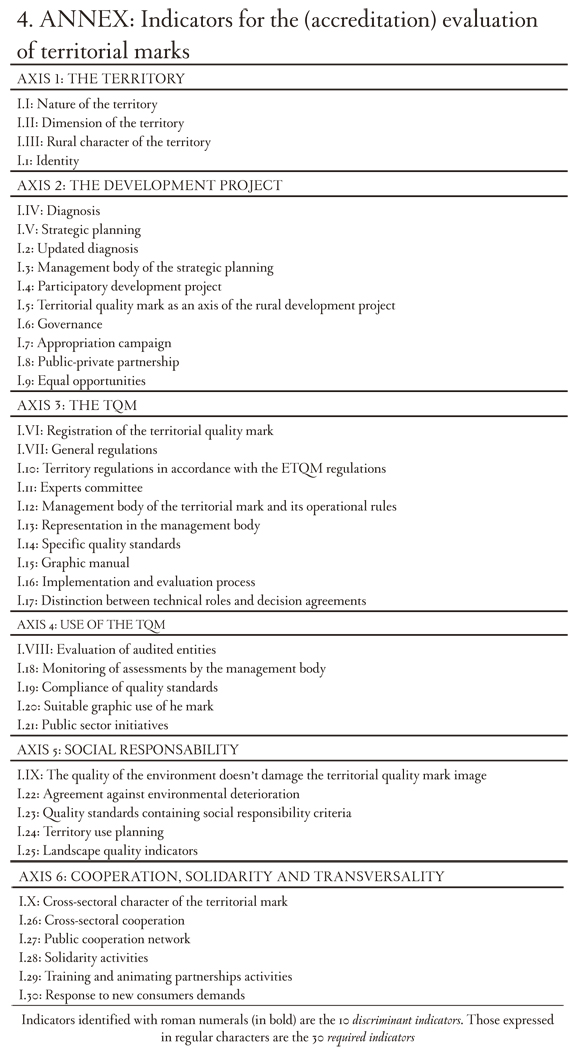

The methodology uses a broad range of variables, which were identified as relevant following a due process of analysis9. The combination of these variables has resulted in 40 indicators grouped into the following thematic axes (Garrido, 2014):

- The Territory (16 variables-4 indicators): Viewed as a social construct; a living entity with multiple facets (economic, social, institutional, environmental, cultural, etc.). The indicators belonging to this axis are related to the nature, dimension, rural character and identity of the territory in which the quality mark strategy is developed.

- The Development Project (40 variables-10 indicators): The future vision of a territory captured in a development strategy must be consistent with the strengths and opportunities of the territory and overcome its major weaknesses and threats. This axis includes indicators to analyze: a) the diagnosis; b) the strategic plan; and c) mechanisms of participation and governance as well as other relevant issues.

- The Territorial Quality Mark (46 variables-10 indicators): The level reached by the territory in terms of defining its mark and its quality assurance system. This includes aspects related to the quality standards, management tools and procedures, monitoring bodies and visibility strategy inside and outside the territory in question.

- Use of the Territorial Quality Mark (28 variables-5 indicators): The variables included in this axis analyze issues such as the certification of the specific territorial quality mark carriers, process monitoring and control, compliance with different quality requirements of quality and graphic use of the mark.

- Social Responsibility (27 variables-5 indicators) : The carrier companies and entities involved in a process of territorial quality should be economically viable, environmentally friendly and committed to the advancement of society. This axis includes indicators to measure the level of implication of the stakeholders involved in the quality mark strategy for that social responsibility purpose.

- Cooperation, Solidarity and Transversality (28 variables-6 indicators): The variables of analysis of this axis aim to assess the type, intensity and impact of the internal and external synergies that have been created, fostered or strengthened by the territorial mark. Training and animating partnerships, as well as those issues related to consumers' demand are also included.

Constructing the evaluation indicators (EU Network level) aimed at providing them simplicity, relevance and objectivity. Accordingly, the essential information required for the definition of each indicator is the following: a) name and purpose, b) reasons to be used, c) objective sources to calculate its value, d) calculation procedure, and e) scale to be used (quantitative and qualitative variables are identified in order to get the indicator value, depending on its nature).

3.3. Evaluation protocol

The methodology for accreditation of Territorial quality marks is applied through collecting, verifying and analyzing evidence10 as a way to measure the degree to which each of the 40 indicators has been achieved. To simplify the comparison and incorporate the results, the degree to which each indicator has been achieved is calculated using semantic scales, which assign values in the range 0-100.

The main sources used for gathering evidence are: a) official documents related to decisions made on the marks (provided by the managers of the territorial quality marks); b) interviews with technicians, politicians, and members of the business sector and the social sector.

To correct for possible subjective deviations of the evidence, the indicators are evaluated by means of an objective and standardized process as follows:

- Initial subjective evaluation: This is carried out by each evaluator following a Guide that outlines the criteria for evaluating (and validating when necessary) the evidence, and a System for coding the interviews.

- Objectification of values: This is accomplished by analyzing deviations from the values assigned by each evaluator to the information collected for each mark and territory.

- Standardization of values: Typification of results for the full set of indicators in all the areas analyzed. Following this step, a panel of experts corrects the evaluation criteria where appropriate.

The evaluation of each territorial mark takes from four to five months, and is carried out over three following stages: a) the first stage (document auditory) functions as an initial filter using 10 discriminant indicators; b) the second stage (document auditory + fieldtrip) is dedicated to the bulk of the evaluation as it measures the level of fulfillment of practically all the indicators (required indicators)11; c) the third stage is aimed at analyzing the results of the evaluation.

The first two stages of the evaluation require the collaboration of stakeholders. Given that collaboration is key to the methodology, a series of tools (templates, guides and protocols) were designed to facilitate this task due to its strong outreach component.

3.4. Protocol for the analysis of results

To simplify the analysis, better understand the results and facilitate comparisons between the territorial marks that have been evaluated, the score obtained for each indicator is represented using a similar radial diagram as that presented in Figure 1.

Each indicator can take values within the following ranges: Poor (not achieved if the value is less than 50); Good (50-74.9); and Very Good (greater than or equal to 75). For purposes of interpretation, the following criteria were adopted:

- Scores below 50 points are considered as weaknesses in the process to implement and develop the territorial mark.

- Scores between 50 and 75 points reveal areas in which work has begun to build the brand, but where further progress is needed to ensure that it is correctly implemented and achieves the expected outcome.

- Scores above 75 identify the main strengths (real or potential) of each territorial branding strategy. These are the strengths on which the territorial mark must work on its road to excellence within a process of continuous improvement. These results provide a benchmark and a model for developing best practice guides.

Concentrating the values of all the evaluation indicators in a synthetic index allows comparing results among territories and undertaking other deeper analysis. According to the theoretical debate (Dillon & Goldstein, 1984; Johnson, 2000), the Territorial Quality Mark Development Degree (TQMDG) has been defined by using the Main Components Analysis to build up the synthetic index. TQMDG is then used to establish a typology of territories based on a set of criteria, including among others: a) degree of progress; b) type and intensity of use; c) degree of public prominence; d) degree of commercial activity; e) interpretation and incorporation of intangible elements; and f) level of mainstreaming. In addition, quantifying the TQMDG for all the territories belonging to the European project is the first step to identify those factors that better explain the degree of success of rural territorial development based on territorial quality. Results of this analysis will be disseminated through future publications.

3.5. Verification and application

The proposed methodology was subjected to a pre-validation process in three pilot territories12 according to the following sequence:

- Verification of consistency: This is designed to test the ability of the methodology to analyze the coherency and adequateness of the approach taken by each local territorial mark under the umbrella of ETQM.

- Verification offlexibility: This is used to verify the applicability of the methodology in different rural scenarios and to local marks with different levels of development.

- Verification of usability: This is aimed at gauging the viability of the methodology in relation to the role of the evaluators and the stakeholders consulted.

The methodology has been applied to evaluate 15 Spanish territorial marks to complete the validation process. The satisfaction of the territories involved in the (qualitative) validation has been very high. This satisfaction stems from the fact that all of them considered the methodology to be appropriate for identifying and assessing, in a very realistic manner, the tangible and intangible elements of the development processes and the use of territorial marks. In other words, the methodology permits identifying and rigorously analyzing what professionals in the territories know are the strengths and weaknesses of the projects they are working on. The application of the methodology to a larger number of territorial marks will allow the methodology verification from the statistical point of view.

Conclusions

Second generation labels can become effective instruments for the development of rural territories in a future scenario characterized by increasing market competition and European budget cuts. The European Territorial Quality Mark Project, and its Rural Quality® label, is a second-generation label with a very high potential in line with the Quality Package 2010 of the European Commission.

These marks must be based on a sound system of management that is both objective and transparent, and which contributes to the promotion of tangible and intangible territorial specificities to generate income and wealth (in terms of economic, social and environmental quality) in the territory.

The proposed methodology is of a remarkably innovative and multidimensional character that is highly relevant and of interest due to the absence of similar methodologies in this field. The methodology responds to the challenges of identifying and rigorously assessing the factors that best explain the degree of development of territorial branding.

- The representation of the results in the radial diagram, in an understandable way, a large amount of information that is easily transferred to those involved in the implementation of a territorial mark (technicians, and political, business and social representatives).

- The systematization of the results, using synthetic index can produce very relevant information for the analysis of factors hindering success and potential that is not fully exploited in the implementation of territorial marks, making it a useful tool for carry out benchmarking tasks and identifying best practices.

Acceptance by local stakeholders of the results and the procedure followed in the evaluations conducted so far attest to the capacity of this methodology to address the proposed objectives.The methodology presented here can be applied to other projects and contexts of a similar nature (replicability) as: a) it can be easily adapted to evaluate other second generation labels; and b) has a great potential for analyzing other dynamics of territorial rural development rather than labels.

Foot Note

1The effects of globalization of particular interest to this work include: a) the integration of consumers, companies and farmers in a single sphere; b) deal directly with changes in demand through variables that influence the manner and place of production (Swinnen, 2009).

2This greater effort is typically focused on: promoting trade, improving the certification scheme, better transparency and traceability, etc.

3This term, which is used in the field of thermodynamics, is employed figuratively here to mean "disorder".

4Agricultural Farm Products and Foodstuffs: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/list.html Wines: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/markets/wine/e-bacchus/ Spirits: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/spirits/

5During this consultation period, three key elements were identified for the development of a comprehensive agricultural product quality policy: a) information (improving communication between producers, distributors and consumers); b) coherency between different policy instruments; and c) complexity (simplifying the scheme so that it is easier for both producers and consumers to understand and therefore use).

6These territorial assets would be doomed to the drama widely discussed by Hardin (1968), which could lead to their overexploitation or loss if their use is not addressed in this collective and consensual manner.

7The European Initiative LEADER (Liasons entre activités de Development de L'Economie Rural) has been carried out in 3 stages: LEADER I (1991-1995), LEADER II (1996-1999) and LEADER+ (2000-2006).

8The certification evaluation for both products and firms runs under a series of requirements (the so-called Specific Quality Standards, one per sector) that are applied by external auditing companies, as required in the ETQMP.

9The process used to identify the variables was to: 1) determine the core elements of a rural development strategy based on quality; 2) analyse and compare the monitoring and evaluation methodologies used in different quality assurance schemes; 3) consult with technicians from a range of rural development groups; 4) conduct interviews with qualified informants in rural areas with different territorial dynamics.

10For the purposes of the evaluation methodology, evidence refers to all records, statements of fact, sampling data or any other information that is relevant to the evaluation process, provided that the information is objectively verifiable. Broadly speaking, evidence can be obtained through: 1) reviewing and auditing documents; 2) direct observation and visual evidence in the field; and 3) in-depth interviews.

11In this stage, an on-site visit is made where primarily non-documentary evidence is collected and verified.

12The territories selected for validation were: Valle del Ese-Entrecabos in Asturias, and the Condado de Jaén and Los Pedroches in Andalusia. These territories were chosen as they were representative, were at different phases of implementing the scheme, and presented very different characteristics.

References

Becker, T. & Staus, A. (2008, August). European Food Quality Policy: the Importance of Geographical Indications, Organic Certification and Food Quality Insurance Schemes in European Countries. Presented at the 12nd EAAE Congress. Ghent (Belgium). [ Links ]

Belleti, G., Marescotti, A. & Moruzzo, R. (2003). Possibilities of the New Italian Law on Agriculture. In G. Van Huylenbroeck & G. Durand (Eds.), Multifunctional Agriculture. A New Paradigm for European Agriculture and Rural Development (pp.143166). Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Dillon, W. & Goldstein, M. (1984). Multivariate Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

European Commission (1996). SEM 2000 Communication on Evaluation, 8 May 1996, Concrete Steps towards Best Practice Across the Commission. SEC 96/659 Final. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (1999). Spending more Wisely: Implementation of the Commission's Evaluation Policy. SEC 69/4. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2000). Protected Designations of Origin and Protected Geographical Indications in Europe: Regulation or Policy? FAIR 1-CT 95- 0306, Final Report. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of LEADER+ Programmes. Document VI/43503/02-Rev.L Agriculture Directorate-General. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2008a). Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength. COM-616 Final. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2008b). Green Paper on Agricultural Product Quality: Product Standards, Farming Requirements and Quality Schemes. COM-641 Final. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2009). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on Agricultural Product Quality Policy. COM-234 Final. Brussels. [ Links ]

European Commission (2010). Quality Package 2010. Last access on June 18 2013, from http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/policy/quality-package-2010/index_en.htm [ Links ]

European Court of Auditors (2011). Do the Design and Management of the Geographical Indication Scheme allow it to be effective? Special Issue Ns 11. Brussels. [ Links ]

European LEADER Observatory (2000, November). Mejorar la calidad de las evaluaciones ex-post de LEADER II. Brussels: European LEADER Observatory. [ Links ]

Frayssignes, J. (2011, November). Marques territoriales et développement rural: lecture critique pour la construction d'un programme de recherche. Presented at the Colloque International & Interdisciplinaire Labellisation et "mise en marquee" des territoires. Clermont-Ferrand (France), Université Blaise Pascal. [ Links ]

Garrido, D. (2014). Rural Territorial Development Strategies based on Quality Differentiation Linked to Geographical Origin: the Case of the Rural Quality Mark in Spain. Córdoba: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba. [ Links ]

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, 1243-1248. [ Links ]

Henchion, M. & McIntyre, B. (2000). Regional Imagery and Quality Products: the Irish Experience. British Food Journal, 102(8), 630-644. [ Links ]

Ilbery, B. & Kneafsey, M. (1998). Promoting Quality Products and Services in the Lagging Rural Regions of the European Union. European Urban and Regional Studies, 5(4), 329-341. [ Links ]

Ilbery, B. & Kneafsey, M. (2000). Registering Regional Specialty Food and Drink Products in the United Kingdom: the Case of PDOs and PGIs. Area, 32(3), 317-325. [ Links ]

Jonhson, D. (2000). Métodos multivariados aplicados al análisis de datos. México D.F.: ITP. [ Links ]

Lorenzini, E. (2011). Territory Branding as a Strategy for Rural Development: Experiences from Italy. Presented at the 51st Congress of European Regional Science Association. Barcelona, ERSA, University of Barcelona. [ Links ]

Marangoni, L. (2000, November). La metodología de evaluación de las especificidades de LEADER aplicada a los GAL de Emilia-Romagna. Presented at the Seminar Mejorar la calidad de las evaluaciones ex-post de LEADER II. Brussels: European LEADER Observatory. [ Links ]

Marescotti, A. (2003, September). Typical Products and Rural Development: Who Benefits from PDO/PGI Recognition? Presented at the 83rd EAAE Seminar. Chania (Greece). [ Links ]

Midmore, P. (1998). Rural Policy Reform and Local Development Programmes: Appropriate Evaluation Procedures. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 49(3), 122-139. [ Links ]

Pecqueur, B. (2005). Le développement territorial: une nouvelle approche des processus de développement pour les économies du Sud. In B. Antheaume y F. Giraut (Eds.), Le territoire est mort, Vive les territoires! (pp. 295-316). Paris: IRD Editions. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. (1993). The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life. The American Prospect, 4(13), 78-87. [ Links ]

Ramos, E. (Coord.) (2008). La marca de calidad territorial: de la reflexión inicial a la implementación de la Red Calidad Rural. Santisteban del Puerto: Asodeco. [ Links ]

Renard, M. (1999). The Interstices of Globalization: the Example of Fair Coffee. Sociologia Ruralis, 39(4), 484-500. [ Links ]

Segrelles, J. (2000). Desarrollo rural y agricultura: ¿Incompatibilidad o complementariedad? Agroalimentaria, 6(11), 85-95. [ Links ]

Sylvander, B. (1995). Conventions de qualité, marchés et institutions: le cas des produits de qualité spécifique. In F. Nicolas & E. Valceschini (Eds.), Agroalimentaire: une économie de la qualité. Paris: INRA, Economica. [ Links ]

Swinnen, J. (2009). Reforms, Globalization, and Endogenous Agricultural Structures. Agricultural Economics, 40(6), 719-732. [ Links ]

Thirion, S. (2000, November). El método SAP en Portugal (Sistematización de la Autoevaluación Participativa). Presented at the Seminar Mejorar la calidad de las evaluaciones ex-post de LEADER II. Brussels, European LEADER Observatory. [ Links ]

Trognon, L. & Delahaye, H. (2011, 8-10 November). Le label Eco-Quartier: entre marketing et projet de territoire. Presented at the Colloque International & Interdisciplinaire Labellisation et "mise en marque" des territoires. Clermont-Ferrand (France), Université Blaise Pascal. [ Links ]

Ulloa, R. & Gil, J. (2008). Valor de mercado y disposición a pagar por la marca "Ternasco de Aragón". Revista Española de Estudios Agrosociales y Pesqueros, 219, 39-70. [ Links ]

Vandecandelaere, E., Arfini, F., Belletti, G. & Marescotti, A. (2010). Uniendo personas, territorios y productos. Guía para fomentar la calidad vinculada al origen y las indicaciones geográficas sostenibles. Roma: FAO, Sinergi. [ Links ]