Introduction

Rural development has been described as a complex or ‘wicked’ problem because it involves many challenges and engages many people. Rural development is difficult to tackle because it has been inadequately understood due to all the connections among its problems. The actors interested usually differ in the best manner to address and manage rural development concerns; that is why the policymakers of rural development have been unable to solve all the issues involved. In such scenario, tackling rural development needs an organised process.

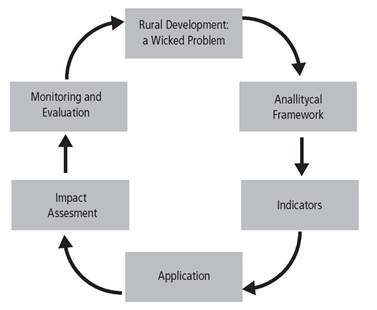

Making a systematic attempt to deal with complex problems such as rural development is a challenge for policymakers, academics, students, and professionals. A standard process (Figure 1) should start with a comprehensive analysis, and hence, the complete understanding of the entire problem. Once that step has been carried out, the next one is the characterisation of the causes and consequences of rural development issues. In order to do so, it is necessary an analytical framework that integrates as many elements of the rural development problems as possible. The next two steps should be the construction of a strategy and its application, usually based on indicators, to identify what is occurring in the rural territories. Thereafter, the next step is the assessment of the possible impact of public policies on the countryside, usually taking into account the indicators defined previously, which aims to identify the best public policy option to be executed in the territories. The final step, after the implementation of the policy, is the monitoring and evaluation of the results of that execution. This step is usually carried out years after the implementation of the public policy. As a result, new problems must be identified, and frequently the process starts again with new challenges to be solved (Australian Public Service Commission, 2012; Probst & Bassi, 2014; Vennix, 1999).

Due to the importance of involving different stakeholders in the public policy concerns, in this particular case the public policy of rural development, it is necessary to remark the importance of the evaluation of the impact of public policies. The assessment of a public policy could be understood as a systemic process of observation, analysis, and measurement that seeks to verify the effect of a particular intervention on the resolution of a certain social problem that affects a group of people. An evaluation also aims to find the possible gaps that have not been covered, but fundamentally it seeks to find elements to prepare future interventions. In other words, the evaluation of the impact of a public policy seeks to confront the validity of a given process (Vargas, 2009).

As mentioned above, rural development approaches have dissimilar points of view. For this reason, the participation of different actors along the public policy cycle is crucial, especially of those whom the policies will affect. This fact will certainly give an important characteristic to public policies that is the legitimacy of the process (Roth, 2002). Given this scenario, the involvement of the populations that suffer the daily problems in rural areas in the evaluation process of public policies is one of the goals that an integral approach to rural development must pursue in itself. However, this participation must transcend the mere fact of providing information. It should be a scheme in which rural inhabitants can exert an impact on the decisions that will ultimately affect them. This effect can clearly be established through processes of continuous monitoring of the impact that interventions have on the reality that people live in rural areas.

According to the previous scheme of the cycle of a public policy, an analysis of the rural development perspectives shows a lack of a comprehensive approach to tackle a wicked problem such as rural development. Pachón, Bokelmann, and Ramírez (2016a) describe the strengths and weaknesses of the main approaches and their perspectives to put forward the Political Approach represented by the Food Sovereignty Perspective.

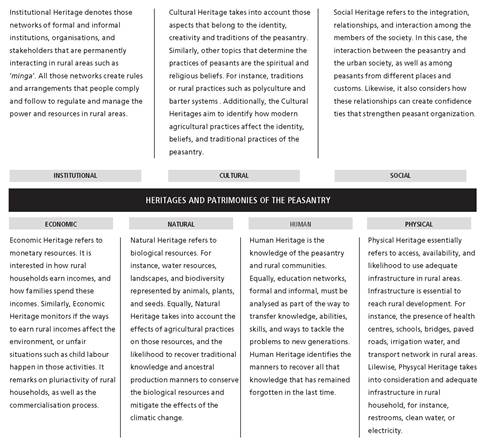

The next step in the cycle corresponds to the proposal of an analytical framework called Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry, which remarks seven heritages: Social, Cultural, Human, Institutional, Economic, Natural, and Physical, that involve the traditions, mores, identity, knowledge, and practices of the peasantry. The level of these heritages determines the level of rural development in a territory (Pachón, Bokelmann, & Ramírez, 2016b). The analytical framework understands rural development as the process to improve the quality of life while respecting the rights of all rural inhabitants. Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry takes the main thoughts of the major rural development approaches but is especially based on the Food Sovereignty Perspective, which takes the idea of the acknowledgement of the rights of rural people as the centre of the rural development discussion. The fundamental characteristic of the framework is a multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary methodology that allows taking into consideration the opinions of as many stakeholders involved in the rural debate as possible (Figure 2).

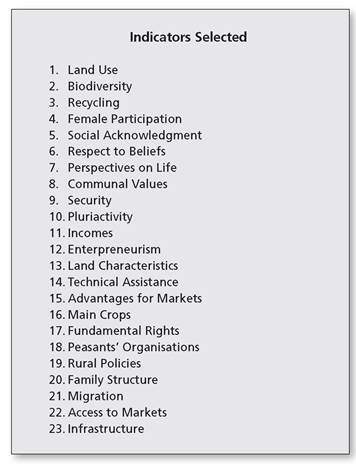

The next step in the cycle of a public policy aims to select the indicators that will describe the current condition of the seven patrimonies described previously. These indicators were chosen through a structured methodology that allowed establishing the most relevant aspects of the rural development discussion. The method started with a comprehensive literature review to organise the first list of indicators, which later on was adjusted in a set of 87 relevant topics according to the relationship between them. Then, a panel of experts assessed all the topics using the methodology of the Vester’s Matrix, after which 37 indicators remained. In the next selection phase, the indicators were graded according to the characteristics of a good indicator using an online survey and these results were interpreted statistically using a Principle Component Analysis (Pachón, Bokelmann, & Ramírez, 2015). Finally, a set of 23 indicators was selected (Figure 3).

Following the cycle of a public policy, the next step was the application of the set of indicators and the analysis of the findings based on the analytical framework Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry. The application was carried out in twelve different regions, six from Colombia and six from Mexico. In Colombia, the results showed a low level in the Physical, Natural, and Human Patrimonies based on 207 face-to-face interviews. The isolation of rural areas located far away from the principal cities was determinant at the moment of accessing governmental services; that is why topics such as infrastructure, technical assistance, or education were scarce in those areas. On the contrary, the rural areas nearby principal cities had an adequate availability of governmental services, and hence, better access, for instance, to markets, health services, and education. A crucial aspect was the challenge of topics regarding the Natural Heritage. In relation to it, the peasants remarked problems such as aerial fumigation of illegal crops and its consequences (Pachón, Bokelmann, & Ramírez, in press).

In the case of Mexico, 193 face-to-face interviews were carried out. Natural and Human Heritages were classified at a low level. It was remarkable that the Mexican peasantry of two regions interviewed was recovering its traditions, finding in such process economic alternatives to get income. However, that process was creating problems related to alcohol consumption, and consequently, domestic violence. Migration was highlighted as a huge problem in rural areas, because young people prefer to look for job options in other countries, instead of working on their farms.

The results showed that a profitable crop such as avocado has a positive impact on some rural development indicators, and hence, on the heritages, but at the same time, it has a negative effect on some others. In other words, the presence of a crop that holds obvious economic advantages in a region does not mean that heritages such as the Natural, Cultural or Social Patrimonies get a high level (Pachón, Bokelmann, & Ramírez, 2016c).

The application of the analytical framework and the indicators opens a gap to fill in the decision-making cycle, which is the assessment of the impact of public policies on the indicators, and hence, on the patrimonies of the peasantry. In such context, this paper aims to identify the potential implications of some public policies on the rural development indicators and Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry in Colombia and Mexico, and as a consequence, it intends to recognise the underlying effects in the process of improving the quality of life and the respect for the rights of all rural inhabitants. In other words, the possible impact on the rural development level.

The findings of the current research will be useful for the stakeholders involved in rural challenges. For instance, peasants could be able to identify the potential impact of policies on their life and then participate in the construction of public policies that take into consideration their opinions regarding rural development tasks. On the other hand, the methodology would be practical for the government because it allows to identify the perception of the rural actors regarding the policies proposed. Likewise, it will be beneficial to professors, students, and research centres of universities because it is an alternative to analyse rural development problems taking into consideration the potential impacts of policies.

Methodology

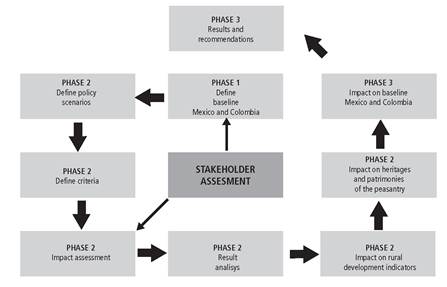

The current research uses the Framework for Participatory Impact Assessment (FoPIA) to identify the potential impact of public policies on the rural development indicators and Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry in Mexico and Colombia. Morris, Camilleri, and Moncada (2008) describe FoPIA as a method that allows the assessment of potential impacts of policies at the national, regional, or local level, and it is an opportunity to bring the knowledge and expertise of the stakeholders involved in agricultural policies into a rational debate. FoPIA has been used to conduct impact assessments of participation-based policies at a case study level using stakeholder and expert information. Similarly, it has been widely used to evaluate the impact of land use policies at a regional and local level (Bezlepkina, Brouwer, & Reidsma, 2014; König et al., 2010, 2013) as well as to assess sustainability policies at a national level (Morris, Tassone, de Groot, Camilleri, & Moncada, S., 2011; Purushothaman et al., 2013). Figure 4 shows a scheme of the methodology that was used, which was organised in three phases.

First Phase

The first phase, described previously, consisted of the construction of a baseline of rural development indicators examined with the Heritages and Patrimonies ofthe Peasantry analytical framework in Mexico and Colombia (Pachón et al., 2016d, 2016c).

Second Phase

The second phase starts with the definition of the policy scenarios that will be assessed by the stakeholders. Figure 5 shows the three policy scenarios for each country.

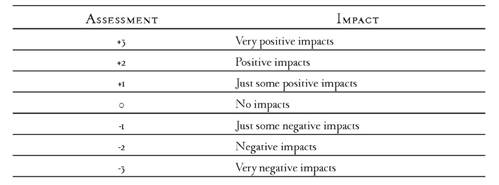

The next step is the impact assessment of the policies on the rural development indicators. Afterwards, the stakeholders were requested to assess the potential impact the policies would have on the indicators according to their knowledge and expertise. Annex i shows the rural development indicators and criteria used to assess the impact. The impact was assessed according to the scale, using an online survey software (Figure 6).

Third Phase

The last phase was to analyse the results of the impact assessment completed by the participants. The analysis was done initially on the indicators and then on the Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry in both countries. Later, a comparison with the baseline from each country was carried out to verify the impact of the policies, and then to structure the recommendations in order to improve the quality of life while respecting the rights of all rural inhabitants.

Results and Discussion

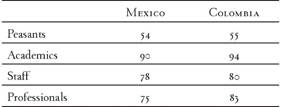

Figure 7 shows the number of participants in the online survey organised in four different groups. Summing up, 609 stakeholders, 297 from Mexico and 312 from Colombia, graded the impact of the policies.

Mexico

Impact Assessment on Rural Development Indicators

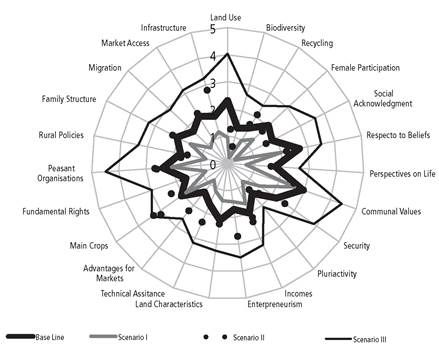

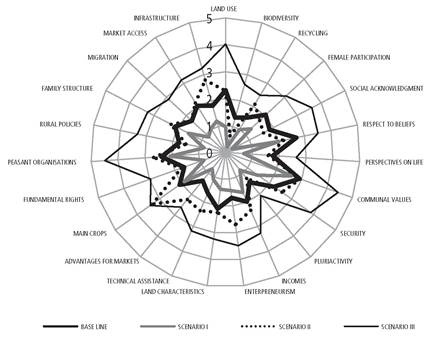

Figure 8 shows the impact assessment defined by the participants in the survey. In general terms, all the indicators had a positive impact in all the three scenarios. In the case of the indicator Pluriactivity, the positive impact was minimum, and the level remained almost equal to the baseline. According to the participants, none of the policies will influence members of the family to stay working off the farm. However, the impact of the indicator Migration was positive, and narrowly related to Pluriactivity.

The indicator Perspectives on Life had a slightly positive impact in the three scenarios, and it was higher in scenario III with the Programme Promete. The topics assessed for this indicator were the habits of resting on rural areas, the perspective about the future of rural areas, alcohol consumption, and attention to women during pregnancy and after childbirth. The last criterion had the most positive impact on scenario III, which is focused on rural women.

On the other hand, some indicators narrowly related to productive aspects were positively impacted, for instance, Main Crops, Advantages for Markets, Technical Assistance, Land Characteristics, Incomes, Peasant Organisations, Entrepreneurism, and Infrastructure. It is a logical consequence of policies focused mainly on productive aspects. However, it is important to remark that in general, public policies in Mexico regarding rural areas and promoted by the Secretariat of Agriculture -Livestock, Rural Development, Fishery, and Food (Sagarpa in Spanish)- are focused on productive aspects.

The social and environmental aspects of rural development indicators reached a slightly positive impact, perhaps explained by the previously discussed fact that the focus of policies are based on productive and economic aspects. However, it is important to remark that one of the most critical rural development indicators, Biodiversity, graded as lowest in the baseline, reached an improvement in the three scenarios. Scenario II, Integral Rural Development Programme, was slightly more positive than the other scenarios. However, the difference between the Promete Programme and scenario II was minimal but, according to the participants, the positive impact is trifling to make contributions to recover peasant traditions.

Impact Assessment on Heritage and Patrimonies of the Peasantry Framework

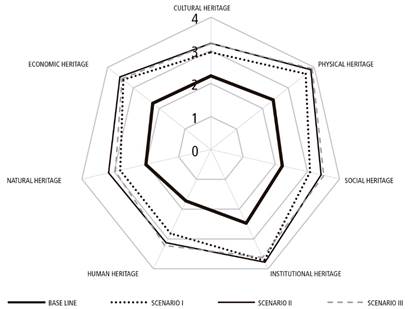

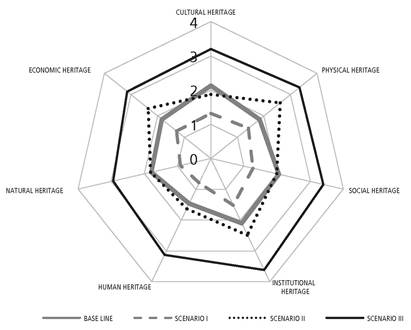

Figure 9 shows the impact of the policies on the Heritages of the Mexican Peasantry. As a whole, the three policy scenarios positively impacted the heritages. Physical and Institutional Heritages were the most positively impacted. On the other hand, Human Heritage, which was the lowest assessed at the baseline, reached a remarkable improvement in its level. On the contrary, in the case of the Natural and Cultural Heritages, the impact was positive but slightly lower than on the other heritages.

Scenario I: Commercialisation and Market Development Programme

In simple words, the goal of the Programme is to support peasants in all the topics regarding commercialisation. In general, the programme of the current scenario got the lowest positive impact on almost all the indicators, and hence its effect on the Heritages of the Mexican Peasantry was minimal in comparison to the other scenarios.

It is interesting to find out that two indicators, the emphasis of which is the markets, got a similar impact to the one obtained in the other scenarios. This means that the perception of the participants about the influence of the programme on its central objective, which is commercialisation, was understood as not significantly important.

It is possible that such perception of the participants in the online survey was influenced by academic analysis (Fox & Haight, 2010; Rubio, 2014) and press releases (Ramírez, 2014). According to the Agencia de Servicios a la Comercialización y Desarrollo de Mercados Agropecuarios -Aserca (2015), corn, coffee, sorghum, and cotton were the most benefited crops by this programme.

Ramírez (2014) analyses the main beneficiaries of the Programme and remarks on the kind of final recipient of the subsidies. Firstly, more than 90 % of the Mexican peasants do not have the possibility to receive such support, which continues to be concentrated on ‘medium and big farmers’; and secondly, several transnational food companies such as Cargill, Gamesa, Bimbo, and Bunge became beneficiaries of these grants. The phenomenon is explained by Rubio (2012), who deeply analyses the model of exploitation and exclusion of the peasants in Latin America, focusing on the Neoliberal era. She clearly explains the evolution of the policies that currently privilege the agro-export business instead of the small-scale and peasant production due to the governmental policies, especially those that allow the capture of grants by transnational food companies.

Scenario II: Integral Rural Development Programme

The main goal of this Programme is to increase agricultural production, looking for the modernisation of the backyard farming located in peri-urban areas and arid zones through technical assistance to promote innovative production. It also aims to stimulate the sustainable use of soil and water through the coordination to integrate different projects in the areas of influence. Finally, it seeks to integrate rural organisations and other similar civil society groups, especially to strengthen value chains.

In such outline, the results obtained on the indicator related to the increment of agricultural productivity, which is main crops, were overcome by scenario I. However, scenario II got the highest level of improvement in two indicators directly related to the improvement of production: land characteristics and land use. Likewise, the indicator technical assistance got a superior level in the other scenarios. On the other hand, the impact on the Patrimonies shows a slight increment in some of them. For instance, Natural Patrimony got the highest improvement, followed by the Economic Heritage. However, the differences between the scenarios are trifling.

Despite the current positive assessment, according to Luján (2008), policies like these traditionally have had an insignificant capacity to increase agricultural production, and hence are irrelevant to generate a social change because their strategy avoids attacking inequalities in rural areas. In the same direction, Rivas, Bernal, and Rodríguez (2016) describe that Mexico, in a period of less than 30 years, has passed from exporting to importing most of the basic food, especially corn, which is the base of the Mexican diet. Mendoza (2015) remarks the urgency to keep up the times of institutionality and production. She argues that one of the causes why the policy shows trifling results is because the aid arrives when the crop cycles are over, generating problems such as access to expensive credits to cover the needs of production.

Scenario III: Support to Productivity to Entrepreneur Women Programme (Promete in Spanish)

The Programme assessed in Scenario III aims to increase agricultural productivity accompanying rural women to strengthen or start a new productive enterprise. In general terms, it is important to remark that a public policy to support entrepreneurs focused on women will bring extra benefits such as additional family incomes, creating employment alternatives, diversification in the rural economy, and more importantly, closing the gap in the rural public policy that traditionally has focused on men (Trigueros & Prieto, 2016). On the other hand, women’s entrepreneurship brings a message to children since it demonstrates with positive examples the successful participation of women in the professional, economic and productive life.

It draws attention that according to the assessment made by the participants, Scenario III did not get a high impact level in all the indicators, despite the benefits described previously. In comparison with the other scenarios, the indicators directly related to women such as female participation, family structure, or entrepreneurism got a slightly superior assessment. Similar results are evident in the case of the patrimonies. In general terms, all the patrimonies of Scenario III got the same impact assessment that Scenario II. Just social, physical, and human patrimonies reached slightly better results, and coincidentally, these heritages are focused on nonproductive themes, which is the goal of the Programme.

Vargas-Hernández (2016) evaluated the Promete Programme and, based on the analysis of some study cases, the author highlighted that the main weakness of the beneficiary groups was the lack of administrative knowledge. Technical practice and organisation skills were found as the strengths of these groups. However, the lack of a long term vision, derived from management experience, was a key point to determine that the groups created with the support of Promete Programme did not survive for a while after the influence of the policy finalised.

The results of the FoPIA methodology applied in Mexico show a positive impact of the policies analysed on the baseline of indicators and patrimonies, which evidence an important improvement in all of them. However, it is important to remark that in general the rural public policies of the Mexican government have focused on productive matters looking for the improvement of the competitiveness of the agricultural sector in the frame of the North America Free Trade Agreement (Nafta). According to Herrera Tapia (2009), as a result of the application of the Nafta, the subsidies and support scheme of the Mexican agricultural policies were dismantled and replaced by a series of Programmes concentrated on technical concerns.

The current Mexican policies have a neostructuralist orientation because they aim to open agricultural markets, encouraging both national and foreign private investment, trying to take advantage of the competitive possibilities of the Mexican countryside. However, these programmes put the relevant concerns about the political power of the countryside in a second place, and avoid to provide political spaces and more importance to the peasantry at the local, territorial, and national level (Mendoza León, 2015).

Despite the positive results considered by the participants, contradictions between national assessment and the academic point of view regarding the real impact of the policies are evident. While official reports (Coneval, & Sagarpa, 2015) inform about the high coverage of different Programmes, Ramírez (2014) remarks that the Mexican policy has left out more than 90 % of the small farmers, because the target of those policies is the farmers that hold characteristics to improve production. Regarding this discussion Rivas et al. (2016) show that 10 % of the biggest food companies have gotten between 50 % to 80 % of the agricultural subsidies, that is why positive results are evident in those areas where irrigation is available. On the other hand, Zarazúa, Almaguer, and Ocampo (2011) demonstrated that for smallholders the subsidies received, which are not high, became 40 % of the total agricultural incomes. That is why peasants have had to look for other options to earn their livelihoods, such as migrating to other places.

Improving the impact of public agricultural policies in Mexico needs some essential elements. An example is focusing on themes that go beyond agricultural production, which means a long-term vision, but taking into account the participation of peasants in the definition of these policies is even more relevant. Such approach will allow getting over the isolation of rural inhabitants, and hence, avoiding that the Mexican countryside is left alone.

Colombia

Impact Assessment on Rural Development Indicators

Figure 10 shows the assessment of the rural development indicators done by the Colombian participants. Initially, it is important to remark that all the indicators in the case of Scenario III were assessed with a positive impact in comparison with the baseline. In contrast, the indicators in the event of Scenario I were graded with negative consequences. Whereas the results of Scenario II show a positive influence on some indicators, others keep the same level than the baseline and others show negative outcomes.

A general evaluation shows interesting topics such as the indicator Communal Values, represented by the idea of solidarity, which reaches a similar level in Scenarios I and II in comparison with the baseline. However, the positive impact of that indicator in Scenario III was significant, reaching one of the highest scores of all the indicators assessed. The indicator Peasant Organisations showed similar results, which got the highest positive impact for all the indicators based on the advantages that Scenarios II and especially III would create to those organisations.

The topics inquired to assess the indicator Land Use were soil conservation practices, property of the land, and kind of production in the farm. According to the answers, the indicator reached a high impact in Scenario III, while it was especially low in comparison with the baseline in the other scenarios. On the contrary, Pluriactivity was the indicator that got the lowest level of improvement in Scenario III, while the level in the other scenarios was lower than in the baseline. The topics of this indicator were related to members of rural families working off their own farms.

Impact Assessment on Heritage and Patrimonies of the Peasantry Framework

The results obtained by the indicators go in accordance with the impact that they have on the Heritages of the Colombian Peasantry, and the tendency described previously remains (Figure 11). Scenario III presents a strong positive impact on all the Heritages; while Scenario I got a negative impact in all the Heritages in comparison with the baseline. The results of Scenario II show a significant improvement in the Physical Heritage while a minor adverse impact on Cultural Heritage. The other Heritages either remain at a similar level or slightly higher than the baseline.

Scenario I: Policies of Colombian Development Plan 2014-2018

The level obtained by the indicators in Scenario I moves down the level of all the Patrimonies of the Peasantry, and probably, the assessment made by the participants was permeated by the complex social conditions evidenced by the actions of peasants and farmers calling for solutions to rural inhabitants problems. In Colombia, the public policies and the centralised governments have traditionally excluded peasants and small farmers, generating a huge distance between bureaucrats and rural people (Bernstein, 2010; Rubio, 2012).

In Colombia, the design and implementation of public policies for the countryside are responsibility of the head of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) and its subordinated institutions. However, even though the Institutional Heritage was the best scored of the patrimonies, according to Machado (2009), the weaknesses of the Colombian institutionality are evident. Some of these limitations are, for instance, that many of the people entrusted with the application of policies have short contracts and sometimes the experience could be better to that important task. Another classical example is that programmes and grants do not have a longterm target, and are usually assigned by public calls, which exclude small farmers and peasants; even worse, the MADR has suffered a decrease in its annual budget because all these grants were not assigned.

Most of the countries support and protect their agriculture, however in Colombia, policies have a neoliberal tendency, which just protects selected crops such as sugar cane, oil palm, or coffee. The countryside needs, beyond subsidies, policies of public investment in education, roads, health, and participation seeking to overcome the ‘social discontent’ derived from the huge gap between urban and rural spaces and to generate a social acknowledgement. It also requires public investments in roads, electricity, irrigation and drainage, and technical assistance to increase productivity to improve family income (Montaña, 2002).

Scenario II: Zones of Interest for Rural and Economic Development (Zidres in Spanish)

In comparison with the baseline, the level obtained by the indicators in Scenario II shows that the level of Cultural Patrimony decreases; the Economic, Physical, and Institutional Heritages increase, and the Human, Natural, and Social Patrimonies maintain almost the same level.

According to the results, the application of the Zidres law will bring positive consequences for the countryside in the zones it operates. The indicators connected to the patrimonies narrowly related to productive matters (Economic, Physical, Institutional), show an optimistic panorama, which is possibly explained by the fact that the Zidres areas are remote and featured by high costs to reach a profitable production, poor infrastructure, and weak institutions (Eslava Mocha, 2015). This means that any investment will really improve the difficult conditions of isolation of some of these areas. In contrast, the indicators of the patrimonies related to non-productive concerns (Cultural, Social, Human, and Natural) show a different panorama. A possible explanation for this paradoxical result could be given precisely by the same reason argued previously: the isolation of the countryside.

In essence, with the Zidres law the government will leave these responsibilities in private and foreign hands. Hence, the outsiders, often distant from the goals, traditions, and culture of the people who have been living in the country for years, in a kind of a modern feudalism, will make the decisions about production practices, environmental management, or market targets, based just on their economic perspective.

The Zidres law avoids to overcome the problem of the land tenure, and even creates the conditions to aggravate the land-grabbing problem in Colombia described by Grajales (2015) because it allows concentrating the wasteland (Baldíos) in the hands of foreign investors, which goes against the Colombian National Constitution (Uribe, 2016). Interestingly, in this model the production of these areas could support the food security of the nations of origin of the investing companies instead of supporting the Colombian food sovereignty.

Scenario III: Towards a New Colombian Countryside. Integral Rural Reform

As a result of the participants’ perception, the level of all the indicators increases in Scenario III, possibly due to the fact that the social base of FARC-EP is the peasantry, especially those who live isolated and forgotten by the government areas, and consequently, the peace agreement should solve most of the problems of those people (Caballero-Fula, 2016).

The positive results in all the Patrimonies show that for the first time in many years, the Colombian government recognises the structural backwardness of rural areas (Buitrago, 2016), and as a consequence, it proposes a plan to tackle these problems based on the access to governmental services. In other words, the presence of the Colombian institutions in rural areas will overcome the military control and will focus on programmes of infrastructure (e.g. construction of tertiary roads, irrigation and drainage, electricity, and clean water), social attendance (e.g. rural health, housing, and education), and agricultural production (e.g. technical assistance, land tenure, support, credits, and marketing).

Despite the fact that the Institutional Patrimony reached the highest level, and that the weakness of the institutions is one of the most relevant problems of the rural sector, it is not clear how such an ambitious plan can be carried out based on the same institutions and staff. In fact, the Integral Rural Reform covers most of the rural problems. However, several doubts about the successful application of the programmes remain because the same institutions that kept the countryside isolated in the past will be in charge of carrying out the actions to improve rural conditions. On the other hand, the ways to fund all the programmes are unclear, especially in the middle of an economic recession, with low international oil prices, and a high exchange rate.

The results of the FoPIA methodology applied in Colombia show a symbolic effect of a change in politics. In other words, the participants perceive and asses them as positive new and fresh ideas to implement alternative solutions to the countryside problems. This symbolism of change represented in Scenarios II and III reach, in general, an improvement in the level of the indicators and patrimonies assessed. On the contrary, the idea of continuity, to keep doing things the same way they have always been done, as in Scenario I, is graded negatively in all the indicators, and hence, in the patrimonies. It is the recognition of the failure of public policies for rural development applied in Colombia in the last years, especially those that aimed to improve topics related to non-productive concerns such as education, health services, roads, or electricity.

On the other hand, it is striking that despite the fact that Scenarios II and III are contradictory, both were graded with a positive impact on almost all the topics assessed. On the one hand, there is the Zidres policy, which seeks to encourage private investments as the way to improve agricultural production and infrastructure under the supervision of the government, in a kind of neostructuralist approach. On the other hand we find the Integral Rural Reform, which aims to recognise the problems of the peasant agriculture and offers programmes to solve them through substantial public investments with an orientation based on a territorial point of view (Azuero, 2015).

Likewise, the results allow recognising that regarding public policies there are at least two crucial topics to take into account to make better decisions. Firstly, the concern about social exclusion and the acknowledgement of the importance of the countryside by the entire society. This theme is narrowly related to the traditional isolation of rural people and the lack of inclusive policies described previously. Secondly, the inclusion of biodiversity concerns, as one of the indicators graded with negative impact, especially in Scenarios I and II. It is important because some of the current public policies related to mining activities have been criticised from different viewpoints, which include the environmental impact, but especially because in some areas these activities generate more violence and exclusion for rural people (Bohorquez Caldera, 2013; Villar Argaiz, 2014).

Conclusions

The goal of this paper was to identify the potential implications of some public policies on the rural development indicators and the Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry in Colombia and Mexico using the FoPIA methodology. From the methodological point of view, FoPIA is a useful alternative to assess the impact of public policies on previously defined situations, taking into account the perception of diverse stakeholders. FoPIA is a way to give major evidence to people that make decisions for the purpose of defining comprehensive policies and, as a consequence, obtaining better results.

In this case, six different policy scenarios were defined, three from Mexico and three from Colombia, and the participants should assess the impact of these scenarios on the rural development indicators previously identified and graded. The current research used a substantial variation from other examples where FoPIA has been applied. The variation consisted of the fact that the assessment process was done through an online survey. It shows advantages because it allowed covering more participants during more time with a relatively low cost. Likewise, it permitted gathering the perceptions of diverse stakeholders, regardless of location, background, or political view. However, some weaknesses could be identified. For instance, an online survey needs access to the Internet, and in the case of the current research, the participation of peasants could be have been higher. On the same way, the variation avoids the direct dialogue of the stakeholders that are sharing the same space. Nevertheless, based on the results of an online survey, a focus group could be an alternative to a direct discussion among experts.

Regarding the assessment done by the participants in Mexico, the policies must emphasise on topics such as pluriactivity. According to the results of the current research and other evaluations of public policies, a consequence of their application is that agricultural production, especially from smallholders, is decreasing, and for this reason peasants are looking for alternatives to gain their livelihoods in urban areas from Mexico or other countries. Sometimes these are basic jobs and low wages are their main characteristic.

Another theme remarked by the participants in Mexico was that the impact of the assessed policies on the indicator Perspective on Life was almost non-existent. In other words, the level of this indicator remains almost equal in the three scenarios in comparison with the baseline. This indicator assessed, for example, problems with alcohol consumption or the standard behaviour of the peasants regarding the tradition of resting on Sundays, or if they usually enjoy holidays. The public policies must take into consideration, beyond concerns on agricultural production, other topics that are relevant to reach an improvement in the quality of life and respect the rights of the rural inhabitants. In other words, rural policies should offer the likelihood to all rural inhabitants to have access, inter alia, to culture, recreation, or arts that provide options to reach a complete rural development.

The assessment in Colombia shows clear differences among the policy scenarios. Scenario I was graded in such way that all the indicators, and hence the patrimonies, reached a low level in comparison with the baseline. It means a clear disapproval of the policies carried out by the Colombian government in the period 2014-2018. In the case of Scenario II, some specific indicators got the best level, and as a consequence, some patrimonies. The improvement was significant in the Physical Heritage, and moderate in the Economic Patrimony. The other patrimonies remain almost on the same level than the baseline. It means that the policies of Scenario II should take into account critical themes such as biodiversity and the concerns about the loss of traditional seeds and the declining of wildlife as a result of agricultural practices. Likewise, policymakers should allow including social topics at the moment of the application of procedures in scenario II, because these concerns got a low level in the assessment process.

In the case of Scenario III, all the indicators got a high level in comparison with the baseline, and as a result, all the patrimonies reached an improvement in their level. It means that the participants approve the policies proposed in this scenario and think that with the application of the measures projected, the rural population in Colombia will improve their quality of life while their rights are respected. In other words, the appropriate way to reach a better level of rural development in Colombia is the implementation of the policies suggested in Scenario III. However, policymakers must notice the concerns about Pluriactivity and take into consideration that many rural residents, especially young people, are looking for job opportunities in urban areas, with the problems described previously.