1. Introduction

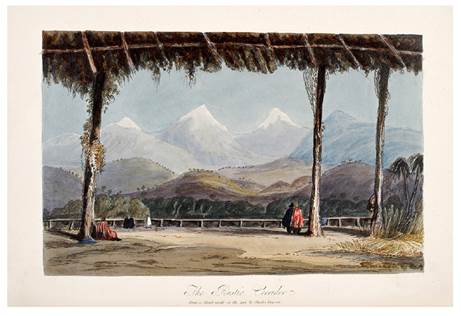

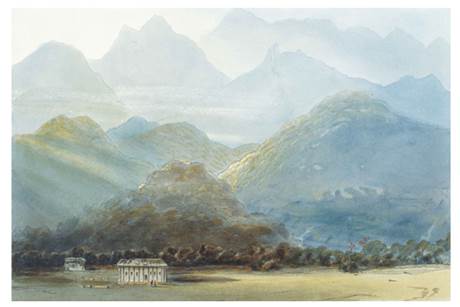

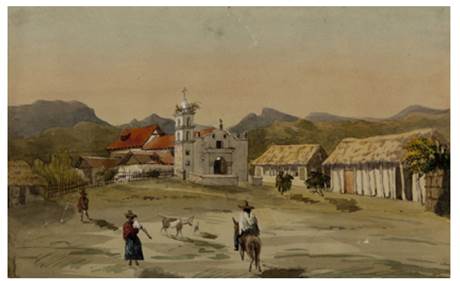

At the beginning of his South American memoirs, British botanist, bookseller and traveler, Charles Empson, mentions Humboldt's “glorious descriptions”1 and the fact that these “...had induced many persons who had no other motive beyond that of beholding Nature in all her majesty, to explore these regions so gorgeously clothed in primeval vegetation, and so abundant in every production interesting to mankind.”2The Rustic Corridor: From a Sketch made on the spot (Figure 1) is one of the twelve watercolors that illustrate the first edition of Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year's Residence in Tropical Regions. The book was published in 1836 after Empson's enigmatic trip. In 1993, physician David Zuck published a brief biographical text on Empson, who was related to recognized anesthesiologist, John Snow. Little is known on Empson's life and work, only that he was baptized on February 1st, 1795 in Yorkshire. In his text, Zuck explains that “[Empson] .tells us that he spent four years, probably during the early 1820s, in what is now Colombia. But he supplies no dates, nor does he say how he was able to finance his voyage and his stay, how he got there and under whose auspices, who his companions were, and what was the real purpose of his visit. These remained complete mysteries”.3

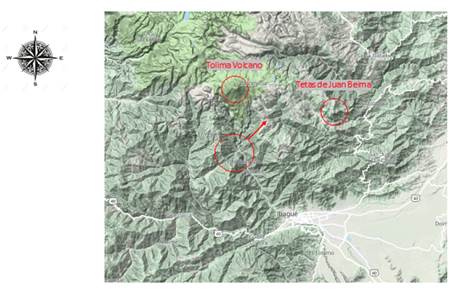

Figure 1 Charles Empson, “The Rustic Corridor: From a Sketch made on the spot by Charles Empson” (etching with gouache and gum arabic, 15.2 x 23.7 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 33-35.

The main source of information about this voyager, lies in his self-authored memoirs. What we can conclude by reading them is that Charles Empson was a part of an important line of British voyagers that explored the territories of current-day Colombia. From commercial relationships to diplomatic postings,

...the British brought to Colombia a specific vision of painting, and they showed Colombians the first images of themselves: the rough roads of the Andes, the towns, the navigation scenes on the Magdalena River, the peasants of Cundinamarca, the ladies of Bogotá, the trades and the festivities”.4

British travelers brought with them their small sketchbooks, watercolors, ideas of the picturesque and the sublime and new versions of how to understand and construct a landscape, as well as strong imperialistic ideas. They promoted mining and economic development in different areas of the country, and imported new notions of nature to a colonial, Catholic-devoted country. Well-known names of 19th Century British visitors to Colombia include, Colonel John Potter Hamilton, Charles Empson, merchant Joseph Brown, diplomat Edward Walhouse Mark and musician-artist, Henry Price. Historian Nancy Leys Stepan explains this strong British influence describing that,

The interest in nature in Britain was related to such factors as the cultural authority of natural theology, which allowed people to see God's work in nature; the development of a leisured middle class, with time and money to spend on gardens and the cultivation of novel plants; and the idealization of the unknown and wild in nature among people for whom an urban environment increasingly defined their daily habitat. The first industrial nation had the greatest of reasons to invest, psychologically and practically, in wildernesses in faraway places.5

This article seeks to deeply analyze one of the thirteen watercolors that Empson made to illustrate his published memoirs through the lens of Humboldtian aesthetics and the act of contemplation. Through a careful visual observation of the drawing and by geographically tracing the place that Empson textually described in detail when he made the sketch, the purpose is to reveal that this specific illustration represents Humboldtian aesthetics applied to mountain observation at a very early time in the 19th century, thus helping construct the influence that voyagers, visiting the young Colombian Republic, had in the construction of tropical landscape as a trope. Part of the methodology used here, includes comparing and critically understanding the abyss that tends to exist between travelers' writings and travelers' images, where texts usually describe reality closer than visual representations, creating an interesting gap between reading the text and understanding the experience through one image only. First, by locating the actual location where the contemplative act took place, and second, by studying the visual components of the drawing as well as its emphasis on the act of human observation, this article studies one image and frames it in the deep and complex study of the relationship between the visual, the textual and the reality of the traveling experience during the first half of the 19th century in Colombian territory.

The Rustic Corridor determines, both formally and conceptually, a series of premises inherited from Humboldt's lessons that can be considered essential to explore the construction of Andean notions of nature. This watercolor characterizes Empson's drawings described as, “...filled with a British picturesqueness turned into watercolor: bridges, mountains, tree trunks and coarse objects that delight the eye...”.6 First, the broad, generic title of this watercolor and its depiction of a specific geographical place that could possibly be identified but whose central purpose is definitely not scientific exactitude, an issue that is also present in Humboldt's graphic work. Second, Empson's intentional representation of an architectural structure whose purpose is to observe the immensity of the snow-capped mountains in the distance. This construction includes two elements: the corridor of a cottage and a balcony that frame and support the act of looking. Third, the importance of subjective observation as the main narrative in the image, in this case locals, dressed in traditional hats and ruanas7, observe the vista either alone or in pairs. In the scene that Empson creates, the campesinos8 escape their productive relationship to the mountains and to the valley beneath them as they stop on their journeys to engage in active contemplation of the landscape. This productive relationship is clearly explained by art historian Francisco Calvo Serraller,

When land has to be bought, neither country nor landscape can exist. A person who is worried about making land productive cannot contemplate the beauty of the land enthusiastically. It is necessary for man to be set free from that heavy burden so that he can look around without the threat of a storm or a draught ruining his economy. This is the only way in which he can truly enjoy the rain, the sunset, the sunrise or the variety of lights and tones that seasons leave behind.9

The illustration appeals towards a feeling of universality where there is a viewer of the mountain range but there is also a spectator watching the onlookers. The solitary beholders of this magnificent place represent a new type of Colombian citizen who, through a rustic window, witness the millenary peaks of the Andes that have now been incorporated conceptually as part of the modern Republic. Like many other travelers, Empson builds this image in resonance with Humboldtian ideas of distance, infinity, splendidness, solitude, observation, interconnectedness and universality while being faithful to Gilpin's British picturesque by seeking the imperfect, the unfinished, the rough and the uneven. This drawing also presents the Humboldtian issue of image and text being inextricable, as the visual representation is meant to do actual work and not just decorate the memoirs, but the gap between the watercolor and the textual description is as deep as the valley it is meant to convey.

2. The place, the description, the geography

Does the place represented in the Rustic Corridor exist geographically? As was common with these travelogues, Empson describes the landscape with more detail in the text than in the image,

On the left is seen the Volcano of Tolyma, and the Promontories which are called Tetas, from the same peculiar form as that from which the Paps of Jura have derived their appellation. On the right are plains, of which you cannot see the termination. Turn round: if you throw your head back sufficiently to obtain the requisite position, you behold the summit of the giant Andes, those ribs of the world, as they have been powerfully denominated, their lofty pinnacles capped with snow, cold, dead, and pallid, during the noontide blaze; but view them again, when saluted by the sun's first rays, - they are tinged with a faint blush, like that on a maiden's cheek, deepening to a roseate hue as the sun ascends, like the brighter colour which betrays emotions that language could not reveal.10

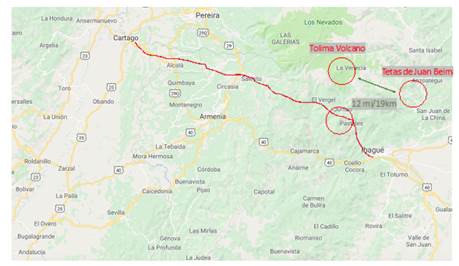

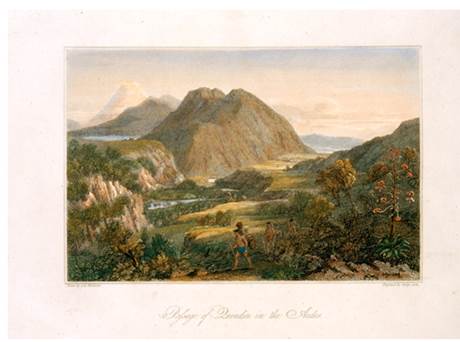

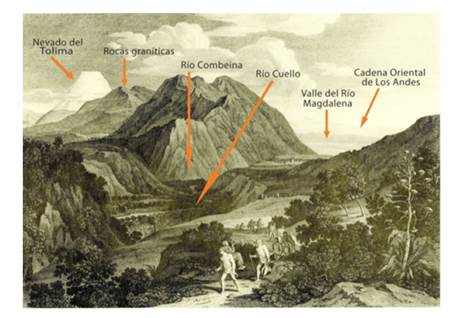

Reading this, we can look at a map and understand that Empson was standing at some point near Las Juntas on the famous Passage of Quindío, the same route that Humboldt and other travelers crossed to get from the eastern to the western slope of the Central Cordillera (Figures 2, 3 and 4). This highly recorded passage allowed travelers to connect from the valley of the Magdalena River to the valley of the Cauca River. The view point is geographically close to that of Humboldt's famous 1808 print, Passage of Quindiu in the Andes (Figure 5). This iconic image, known not only for its depiction of the Andean thermal floors, but for the representation of the cargueros11 has been used constantly as an example of very early nineteenth-century tropical travels. The depth of space described in the print ranges from detailed vegetation in the foreground, to the small town of Ibague in the middle, to the peaks of the Colombian Andes in the background. Humboldt's prints that specifically represent Colombian geography have been previously studied by historian Marta Herrera Ángel who identified the different geographical elements in the image (Figure 6). In Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, published in 1810, Humboldt described this specific site,

The middle range divides the waters between the Magdalena River basin and that of the Río Cauca. It often reaches the perpetual snow line, and it surpasses the latter by far in the colossal peaks of Guanacas, Barragán, and Quindiu. At sunrise and sunset, the middle range presents a magnificent spectacle to the inhabitants of Santa Fé, it recalls the view of the Swiss Alps, but on a more impressive scale”.12

Through this description and the image, Humboldt's need to pair South American nature to European references surfaces, thus allowing European readers to relate to what is described in words and which cannot be encompassed through a few prints. This is a common practice that Leys Stepan has described, “By contrasting the scenery, animals, plants and people at hand with those far away, naturalists instructed and confirmed their readers' sense of European superiority even as they appeared to extol the merits of the foreign.”13 This system, that of finding an equivalent in size, shape, scale or even feeling will be used by travelers throughout the century in order to speak to a wider public seeking the exotic travel narrative.

Empson titles the image, The Rustic Corridor, a name that sets the location in the context of picturesque aesthetics and gives explicit instructions in terms of attitude and pose when he involves the reader, thus evoking eighteenth-century authors such as Gilpin or Payne Knight and their detailed instructions in terms of perception and representation. The fact that the title does not specify geographical exactitude allows for this illustration to capture the imagination of both the reader and the viewer and to act as an avatar for the notion of spectacular Andean views, this place can be and is many places on the Cordillera. It is also the publishing culture of the first half of the century that still prioritized text over image, what conveys voyagers like Humboldt or Empson to find wide, encompassing visual constructions to accompany large written chapters. In Empson's case, this book carries one hand-colored print per chapter, thus allowing the one image to speak for the theme portrayed. The title of the image is the title of the chapter, or vice versa.

Figure 5 Josef Anton Kock / Alejandro de Humboldt, “El Paso del Quindío en la cordillera de los Andes” (copper engraving, 22.2 x 27.1 cm) 1810. In Vues des Cordilléres. Museo Nacional de Colombia.

Figure 6 “Lámina del paso del Quindío con las anotaciones de Humboldt sobre los lugares representados”. Taken from Marta Herrera Ángel, “Las ocho láminas de Humboldt sobre Colombia en Vistas de las cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América (1810)”, Revista Internacional de Estudios Humboldtianos XI, 20 (2010): 112. https://www.hin-online.de/index.php/hin/article/view/138

As viewers of this specific drawing, we are meant to create a visual bond with the faraway magnificence of the mountains and with the people who are standing on the rough and coarse structure of the cottage, contemplating the view in a dynamic act perfectly known to Romanticism and its knowledge of nature as spectacle. This imitates the relationship that Humboldt created between text and image, where his literary description of the crossing of the Quindío region is expressed clearly by González when she says that, “This impeccable landscape with such a clear and wide road contradicts itself with Humboldt's text, where he speaks of the muddled pass and the difficulties found in moving forward.”14 The textual descriptions of these nineteenth-century travel diaries and memoirs are usually more credible than their visual equivalents. This relates not only to issues of literacy, but also to printing costs and an economy of the printed image, as well as to the power of the image in travel literature and the construction of the tropical, exotic landscape. This is what Leys Stepan describes as,

The representation of tropical nature was not a straightforward result of exploration, but rather the product of complicated Western European cultural conventions. By the middle of the nineteenth century, an author could draw upon a number of themes, metaphors, analogies and figures to convey the uniqueness of tropical nature, its otherness, its discursive differentiation from home and the familiar.15

Going back to the geographical analysis of the image, if Charles Empson is standing at Las Juntas looking North-East, according to the actual physical map the approximate distance between the emblematic snow-capped volcano and the Tetas is approximately 12 miles (19 kilometers) which could make sense from Empson's vantage point. However, when we map this angle, it seems unlikely that he can actually see the three promontories as close together as he represents them in the watercolor, particularly off is the distance between mountains number one and number two from left to right (Figure 7 and ). Even if the author did see the peaks at that apparent closeness, where are the other mountains that we know would lie in between, those called Las Damas or The Ladies? Also, the elevation of these mountains on the drawing is very improbable. The volcano on the left is 17,109 ft (5,215 m) and the Tetas have an elevation of 11,568 ft (3,256 m) above sea level. This 5,000 ft. difference is not evidenced in the image, quite the contrary, the middle mountain is higher than the Volcano. Even less likely is the fact that the Tetas de Juanbeima would have had snow at this known altitude. Obviously, this license in geographical truthfulness is due first, to the fact that these published drawings were finished in England years after the trip was completed, they were based on sketches, and depended highly on the memory of the voyager. Second, that the actual function of the colored prints was always that of illustrating, as was already stated, images were, in most cases, contingent to the text.

Abstraction is important when information is recorded, but the challenge comes when creating images that are not necessarily bound to artistic and aesthetic purposes, this is the great epitome between art and science. This problem lies within the difficulties of visually representing, and the literary, narrative description of the world's physical phenomena. Explained by Rachael Z. DeLue in “Humboldt's Picture Theory”, these were some of the challenges faced by the German naturalist when creating the Géographie des plantes équinoxiales: Tableau physique des Andes et pays voisins,

...the sheer quantity and diversity of material available for observation and interpretation threatened to exceed the capacity of exposition, especially if the writer decided to marry truthfulness with style or to produce more than a wearing enumeration of facts. Striking a balance between vision of the whole and its myriad parts- between design and data- proved especially challenging, as suggested by Humboldt's extended discussion in his introduction of the limits of empirical study and experimentation, the imprecision presented by nomenclature, and the problematic divergence of the qualitative and quantitative within scientific methodology.16

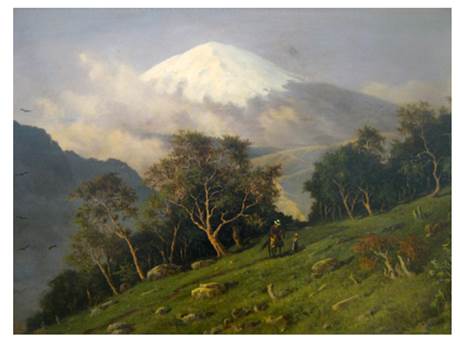

This obstacle becomes evident when contrasting The Rustic Corridor drawing with other examples of images created around the same period and geography. Observing the shape of the Tolima Volcano on various illustrations, most images, including the print already mentioned by Humboldt, intentionally confirm the obviously flattened surface of the crater. The Corographic Commission, an important geographical and regional survey sponsored by the Liberal government of Jose Hilario López in the 1850s, produced images of the same volcano by artists and travelers such as Henry Price17. Other images of the Tolima include those by German painter Albert Berg, who befriended and corresponded with Humboldt, and by Italian painter Giovanni Ferroni (Figure 9) who created a more academic, angled view. In any case, Empson's Volcano seems generalized, schematic and far away from in situ, direct observation. We can debate that a reliable, scientific image of this specific point of the Andes was not his main objective. Quite the contrary, Empson's interest in Humboldtian thought was inclined towards the musings of picturesque effects, such as those found in Views of the Cordilleras, where Humboldt explains,

I was less interested in depicting those scenes and their picturesque effect than in representing the exact contours of the mountains, the valleys that furrow their sides, and the impressive waterfalls formed by plunging torrents. The Andes are to the high Alps what the Alps are to the Pyrenees. Everything romantic or grand that I have seen on the banks of the Saverne in northern Germany, in the Euganean Hills, in the central mountain range of Europe, or on the steep sloped of the volcano of Tenerife- this is all combined in the Cordilleras of the new world.18

Once again, Humboldt compares Andean mountains and valleys to exact equivalents on the Alps. The need to fix the reader's visual dictionary also implies touching base with more ancient geographies, a certain imperial gaze still needed to travel and encompass the Americas. In trying to understand and conceive Humboldt's construction of the pictorial relationship to nature, Marion Heinz explains that, “For Humboldt, painting nature is the scientific result of comprehending nature based on empirical research and on an ideal and thoughtful consideration. The sense that Humboldt gives to this is that of an intellectual intuition of nature as a whole.”19

Figure 9 Giovanni Ferroni, “Tolima Volcano” (oil on canvas, 20.4 x 15.2 cm) 1895. Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia. Banco de la República, Bogotá.

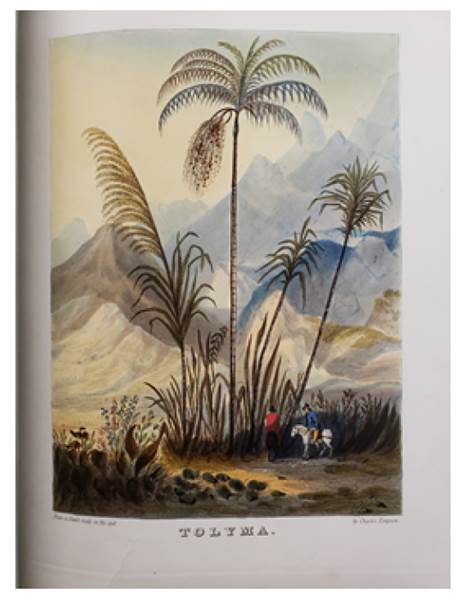

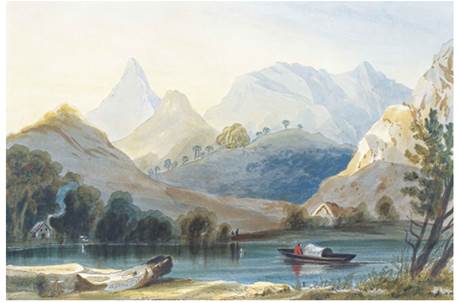

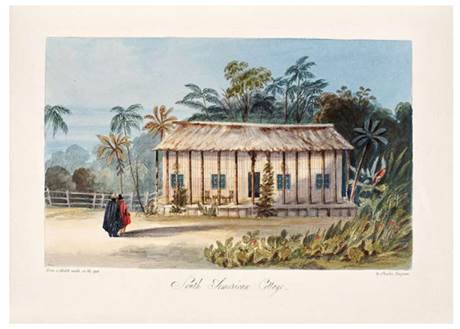

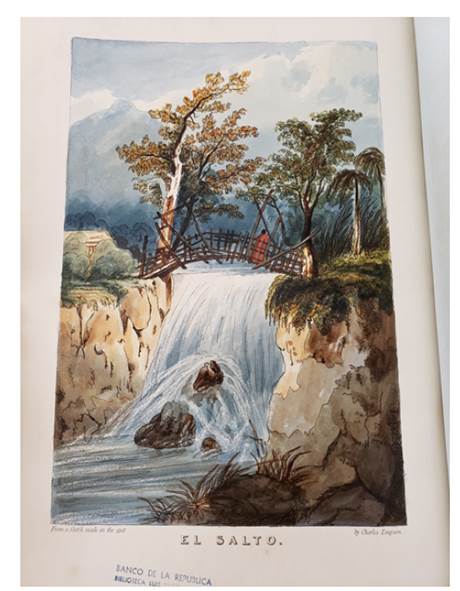

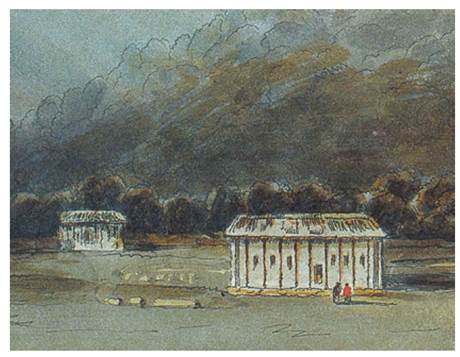

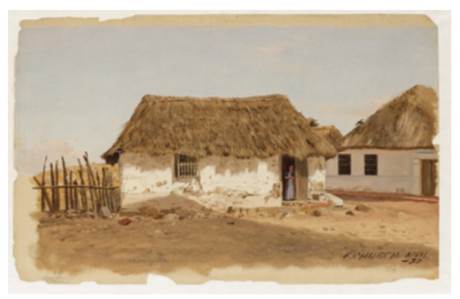

If we compare Empson's Rustic Corridor with other landscapes included in his own published Narratives, it is evident that the botanist is highly versed and trained in watercolor drawing techniques. In most images he intentionally uses formal elements such as atmospheric perspective, proportion and scale, as well as botanical details of plants and flowers that contrast with the open views of the backgorunds. In Peladeros (Figure 10), Tolyma (Figure 11) or Rio Claro (Figure 12), he variates between the represented peaks, with clear differences in the use of light, sharpness, altitude and the specific shape of individual mountains. Foregrounds are highly contrasted, but this can also be attributed to the fact that the Rustic Corridor is unique in its setting and composition because of the indisputable will to frame human surveillance as an act of appropriation. Empson's purpose in depiction has been shifted from nature to the subjects observing the landscape. In South American Cottage (Figure 13) or in El Salto (Figure 14), humans fulfill their role as spectators but the preconceived framed is replaced by other elements such as the hut or the bridge, and, more emphasis is placed on the detailed representation of natural elements like water, palm trees or delicate flowers.

Figure 10 Charles Empson, “The plain of Peladeros, Colombia, looking towards the Cordilleras”(etching with gouache and gum arabic, 15.5 x 23.2 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 105-106.

Figure 11 Charles Empson, “Tolyma” (etching with gouache and gum arabic, 21.7 x 16.2 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 170.

Figure 12 Charles Empson, “Rio Claro” (etching with gouache and gum arabic, 15.6 x 23.4 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 247-248.

Figure 13 Charles Empson, “South American Cottage” (etching with gouache and gum arabic). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836).

Figure 14 Charles Empson, “El Salto” (etching with gouache and gum arabic, 23.5 x 15.7 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 123-124.

3. Intentional representation and human construction

When one looks carefully at these illustrated memoirs, this drawing stands out from the rest because it is the only one that includes the architectural structure that frames the composition. The image shows a balcony where three separate groups of observers look out towards three snow-capped mountains that are centered between three of the structure's visible wooden posts. The composition almost reminds us of more classical visual constructions that have been thoroughly thought-out and studied so as to harmoniously build the image. Canonical, compositions of History painting such as Nicholas Poussin's Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion (1648) or Jacques-Louis David's The Oath of the Horatii (1784) construct a perfectly designed, symmetrical, three-part composition to organize human thought and feeling. When it comes to understanding the natural world under such control, landscapes can risk seeming unbelievable, unrealistic and far removed from the truth.

Charles Empson composed an image that could synthesize the view from one of the slopes of the Cordilleras, an image that would summarize Andean vistas for the whole of his text. This drawing represents both the individual and collective acts of contemplation seen from a specific framework that willingly tries to appear casual, in a system that organizes nature into landscape for the both onlookers in the drawings and the viewers of the image. When Empson described the site in the text, he said,

This sketch was taken from the corridor of a cottage built on the eastern slope of the Andes. Travelers, to whom almost every portion of the globe is familiar, have acknowledged, while gazing upon this spot, that they never held such a sublime spectacle. The real foreground of this splendid panorama could not be represented by the pencil: the dark ravine into which you look, is beautiful beyond conception, extending to the very base of the snow-clad Cordilleras.20

One of the difficulties proposed by the image itself is that of proportion. The author specifically mentions that this structure is the corridor of a cottage, but when the image is analyzed carefully, the size of the beholders seems evidently small in comparison with the height of the supposed cottage and in comparison, with rural cottages throughout the country in general. The height of the posts in no means seems to represent the size of what we may understand by the term cottage. The observers are very small in comparison to the spatial arrangement of this human- built element that is responsible for the act of contemplation. This structure is made compositionally interesting by the horizontal balcony that closes the square frame but leaves enough breathing space on the right hand-side of the image where it is replaced by a small, lonely palm tree. Both the vertical axis, emphasized by the three poles and the palm tree, and the horizontal support of the balcony organize the mathematical space where the organic mountains and slopes can exist as a human- built view. If we compare this framework in proportion with other examples of cottages represented by Empson (Figure 15), Henry Price (Figure 16), or Frederic Edwin Church (Figure 17), the Rustic Corridor looks fairly tall for traditional Andean constructions. If we use an average height of 1.60 meters or 5 feet 2 inches as standard human height, and we multiply this by four times, which seems to be the relation between the human and the pole in the watercolor, this would mean that the cottage has an approximate height of 6.4 meters or 20 feet, a height that could be considered unlikely considering traditional rural Colombian architecture. There is however another possible understanding of this image, and this is the probability that the three long poles are not actually supporting the hut's roof, but that they are taller trees that are actually rooted outside the rustic construction, and thus, in a middle ground.

From left to right, Empson represented first, a lonely seated figure that is reclined on the left column. The figure is apparently male, wears a ruana and a hat and seems to look sideways at the view. The second group is female, judging from the long skirts or coats and is comprised of two women in black and one in white who stands farthest away from the viewer and closest to the actual balcony. The third group on the right is formed by two other figures, not easily identified. One of them wears the same red and white ruana as the figure on the far left. In terms of proportion, the fenced style balcony and the depth in which each group is positioned make the reality of the image a bit strange because the supposed distance between the viewer/artist/traveler is too short in order for each group of figures to be so small. This observation may allow us to say that this image was not made directly onsite and most probably by memory. Katherine Manthorne has explained this challenge in regards to Church when she says that the, “...effort to maintain a verbal commentary running parallel to his images speaks to the need to convey information in a variety of systems, not only to store it but also to verify it once he was removed from the motif.”21

Figure 15 Charles Empson, “The plain of Peladeros, Colombia, looking towards the Cordilleras (detail)” (etching with gouache and gum arabic, 15.5 x 23.2 cm). In Charles Empson, Narratives of South America: Illustrating Manners, Customs, and Scenery: Containing also Numerous Facts in Natural History, Collected during a Four Year´s Residence in Tropical Regions (London: W. Edwards, 1836), 105-106.

The aesthetic use of this frame that allows us to see specific traits or geographical elements of the landscape, is clearly related to Humboldt's pictorial thought and aesthetic influence. Empson read Humboldt's ideas on picturesque landscape and on landscape seen through the language of painting. The well-known fact that Humboldt's descriptions were framed in painterly language allows images like The Rustic Corridor to be seen with these same eyes. Empson, as Humboldt, worked from on the spot sketches, and recognized the difference between his written detailed descriptions of the setting, the mountains, the plants and the animals of a specific place, and the construction of an image that can transport the reader to a universal picture. He was aware of the difficulties encountered between the scientific, the visual and the literary when, in his memoirs, Empson asks, “If painting can only convey a faint idea of the distant mountains, how can language express the emotion produced by the grandeur of a scene, which at one glance reveals to the spectator the extensive range of the majestic Andes, from their broad bases covered with the richest verdure, to their untrodden summits clad with eternal snows, and rising fifteen thousand feet above the level of the ocean?”22

Figure 16 Henry Price, “Tocaima (Province of Bogotá)” (watercolor on paper, 20.2 x 32.6 cm). Colección de Arte Miguel Urrutia, Bogotá.

Figure 17 Frederic Edwin Church, “Two houses in Barranquilla” (brush and oil paint over graphite on paperboard, 31.6 x 44.6 cm) 1853. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution. https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18198997/

4. Subjective observation as narrative

When referencing the pictorial systems that Humboldt recommended to German painter Albert Berg, González details human presence as the second system where, “...the onlooker is generally giving his back to us, contemplating the landscape and, at the same time, serving as topographical reference; the theme is the act of contemplating.”23 We look at this picture and become the traveler just as, according to Humboldt in Views of Nature,

Many times, the impression that the view of nature produces in us is due less to the character of the region itself than to the day in which the mountains and plains appear illuminated by the transparent blue of the skies, or veiled by clouds that near the surface of the earth floats. In the same way, the descriptions of nature impress us all the more vividly, the more in harmony they meet the needs of our sensibility, because the physical world is reflected in the most intimate part of our being with all its living truth. How much a landscape gives individual character: the outline of the mountains that limit the horizon in a distant undecided, the darkness of the pine forests, the torrent that escapes from the center of the jungles and crashes with a crash between suspended rocks, each one of these things has existed, at all times, in mysterious relationship with the inner life of man.24

In The Rustic Corridor, subjective observation is the narrative at stake. Locals, dressed in traditional cold weather clothes and hats, enjoy the view. In this scene the peasants change their relationship to the mountains and to the valley beneath as a place of life and work and engage in active aesthetic contemplation of the landscape. According to Georg Simmel, “.landscape arises when a series of natural phenomena that are found on a piece of earth's crust are regrouped according to a specific type of unit - a unit different from what the sage's look can be considered with his religious thought, that of the peasant or the strategist with his finalist considerations.”25 The Romantic reference to Caspar David Friedrich's Traveler amongst a Sea of Fog (1818) is obviously inevitable understanding the distance in intention, place and use for this particular watercolor. But what happens in this image is that spectators are not outside, they are placed within the framework, as if nature is outside of human view, declaring observation as a cultural, not a natural act.

The subjects in the drawings are not travelers, have no instruments and don't seem to incorporate the need to measure, register or survey, they only look towards the distance. Empson has created a scene that involves fascination and true passive contemplation. The witnesses, divided in groups, do not engage in conversation with each other, have no luggage, transportation or any other evidence of travel plans. They behold the mountains and the fertile valley beneath, a view banned for the viewers of the image as we stand with Empson in the far back. Empson is not solely representing the mountains of the Andes, he is confirming the need of any human being, standing in this place, to stop and behold. The richness of the valley becomes conditional to the height of the mountain range, an evident attitude towards altitude that Simmel says is given, “...only in the snowy landscape does the low seem to lose its rights over things. When the valley disappears, the pure presence of the high prevails: the high is no longer relative but absolute, it is not a high with respect to a certain low.”26

Looking is the theme of this drawing, understanding the experience of gazing and regarding is the main role of the reader in Empson's Narratives. The title of the chronicles emphasizes active participation and narrates the experience of traveling through mountain-clad nineteenth-century Colombia. It summarizes the role of the image in travel literature, the synthesis of the essential and the Humboldtian notion not of representing nature, but of creating an idea of nature, as happens, for example, in Frederic Edwin Church's masterpiece, Heart of the Andes (1854) (Figure 18). These mountains might not be physically exact, even Empson's intention might not have been for us to use GPS location or digitalized maps to discover his exact whereabouts, what is important to understand here is a change in relationship to the landscape. Charles Empson is developing and opening a new space where Colombian inhabitants can stand in awe in front of their own landscape. Appropriation of the land is, in this case as in many, created by the construction of the image, by the integration of nature's elements into a construction brought by European thought.

In Humboldt's words, this watercolor can best be explained in terms of life, imagination and experience. In Views of Nature, published in 1808 before Views of the Cordilleras, the Prussian traveler wrote,

When man interrogates Nature with his penetrating curiosity, or measures in his imagination the vast spaces of organic creation, of how many emotions he experiences, the feeling that inspires the fullness of life universally scattered is the most powerful and profound. Everywhere and even near the icy poles, the air resonates with the singing of birds and the hum of insects. Breathe life, not only in the lower layers of the air, where dense vapors float, but in the serene and ethereal regions.27

British traveler, Charles Empson faithfully understood this premise, and, like others, was fascinated with the new approximation to nature and its construction in landscape terms, produced the image before us, one that would always remind us to stop, stand still, observe, and behold the mountains. In the possibility of standing at any high lookout, both foreign travelers and local population would, after Humboldt, find Schiller's words,

On the mountains there is freedom! The world is perfect everywhere, Save where man comes with his torment.28

Figure 18 Frederic Edwin Church, “The Heart of the Andes” (oil on canvas, 168 x 303 cm) 1859. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In the “Introduction” to his book, Suspensions of Perception, Jonathan Crary explores the relationship constructed during the nineteenth-century between observing, looking and perceiving. This is the primal act not only of travelers but of others who through theories, devices, apparatus and modes if understanding develop a different symbiosis with the world around them. Crary summarizes,

...Western modernity since the nineteenth century has demanded that individuals define and shape themselves in terms of a capacity for ‘paying attention', that is, for a disengagement from a broader field of attraction, whether visual or auditory, for the sake of isolating or focusing on a reduced number of stimuli.29

What is fascinating in Empson's case study is the newly acquired use of this conscious act, in an evidently local population.

The 1820s and 30s are a complex time in Colombia, politically, economically and socially. David Zuck explains that, “South America during the early 1820s was just emerging from the throes of its revolt against the rule of Spain, during which it received much British support. A British Legion some 8000 strong, mainly veterans from the 5 Napoleonic Wars, enlisted in London, but Empson was not of their number. In this he was fortunate, since one observer estimated that of these 8000 only 300 survived, two thirds having succumbed to drink, and the remainder to tropical fevers.”30 The Libertador Simon Bolivar died on December 1830, leaving behind a broken political system of constant feuds between Centralists and Federalist, his famous dream of a “Gran Colombia” shattered. Newly liberated from Spanish colonial rule, the country had great potential, natural resources and an energetic Republican social class, but its geography would be eternally complex for social and economic progress, it's roads unstable, its rivers wild and its mountains uncanny. The country traveled by Empson was recently emancipated, learning to build itself as a modern nation and understanding the challenges of ruling itself. The citizens now left to build the dream of the independent country were still part of what was left of a colonial social class system, while at the same time slowly understanding their relationship to this land.

This land that is being observed, perceived, and lived, is being represented in The Rustic Corridor. A landscape that represents more instinct than truth. Is it possible that Empson is visualizing a landscape framed by Humboldt's notions of nature as calm? If the times when Empson was navigating these landscapes were so convulse, can this high-rise landscape representation represent standing above political issues? Climbing to the top of the Andes to rise above what was happening down below?

By the 1850's through the Corographic Commission, official maps of the Republic were created by Italian geographer and military, Agustin Codazzi. Looking, in the Empson example, is still a matter of faith, of believing what is in front of our eyes. It is still about grandeur and magnificence in a Romantic sense. This is why we cannot completely capture or define the place willfully drawn by Charles Empson on his excursion. The valley below is described by Empson in the text, but it can't be seen in the image. The traveler means for us to understand an approximation of the place, a very thin line between accurate description and subjective experience. This sketchy purpose of representation lies within Crary's explanation of vision being unreliable when he says,

One of the most important nineteenth-century developments in the history of perception was the relatively sudden emergence of models of subjective vision in a wide range of disciplines during the period 1810-1840. Dominant discourses and practices of vision, within the space of a few decades, effectively broke with a classical regime of visuality and grounded the truth of vision in the density and materiality of the body. One of the consequences of this shift was that the functioning of vision became dependent on the complex and contingent physiological makeup of the observer, rendering vision faulty, unreliable, and, it was sometimes argued, arbitrary.31

This balcony where Empson places his subjects and where he places us reminds us of this faulty vision, where what we see might not be exactly what was there, but it is enough for us to capture the meaning, the feeling and the idea of place. Curiously enough, in a manner of formal and chronological comparison, Danish artist Ernest Christian Frederick Petzholt painted around the same time his, Fountain and pergola in Italy (Figure 19), a small oil painting that transports us to the same type of intention, in an even more romanticized world. Although Petzholt does not include the human spectators as such, he means for the viewer of the painting to frame nature, lirerally, through the pergola, in order to create a specific experience of the Italian landscape.

Figure 19 Ernest Christian Frederick Petzholt, “Fountain and pergola in Italy” (oil on paper mounted on canvas, 39 x 50 cm) 1830-35. The Art Institute of Chicago.

An image can say more than a thousand words, and so the narrative description of a place that we don't exactly see, is intentionally condensed, not in one image, but in one human act.

5. Conclusions

When Charles Empson travelled through Colombian territory, the recently independent Republic was beginning to construct it's national identity by reaching out towards nature and landscape. In The Rustic Corridor, Empson created an image epitome of new values and new modes of understanding, not only the natural phenomena of snow-capped mountain peaks in the tropics, but creating images that, seen under Humboldt's premises, would allow for one image to encompass a vast amount of physical, geographical and poetical information.

By intending to abstract a wide sense of place in the Colombian Andes, through the specifics of a particular location described by the author himself, Empson managed to condense Humboldt's notions of universality and landscape painting, while at the same time trying to be truthful with observation and location. This carefully constructed watercolor, represents not only a particular view on the mountains located West of the Magdalena River, but also a particular way of viewing, of framing and of contemplating by drawing those that contemplate. By using one image to illustrate a complete chapter describing the area, Empson promoted representation of truth while at the same time its abstraction. The whole and the part, elements that are present in modern landscape and its influence on Humboldt and on modern travelers to Colombia. As Marion Heinz explains in relation to Humboldt's Cosmos,

_’we mustn't conceive nature as a dead mass, but as a living whole, as a natural system. Within this idea, moving away from logical and artificial classifications, the real order of nature as a complex relational structure of independent parts can be revealed. Seen this way, the spirit of nature is no other than the complete sense of order that underlies everything. This order can only be understood through the empirical research of the particular and through the intuitive comprehension of this close systematic relationship.32

Through the careful study of this image, as one that closely represents many of Humboldt's aesthetic thoughts, one can understand the outreach that images like these had for literary publications during the nineteenth century. One image to represent a variety of ideas and descriptions of places, people and nature. Abstraction of information as a way of conveying scientific truthfulness as well as aesthetic experience. One image, collecting the place, the sense, the uniqueness, the people that are part of the landscape, the architecture that allows us to understand that this is rustic, but not savage, far away, but not unreachable, it is one thing and yet it is everything.