Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Ingeniería y Desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 0122-3461versión On-line ISSN 2145-9371

Ing. Desarro. n.25 Barranquilla ene./jun. 2009

Analyzing the influence of national political and economical factors on the success of public-private partnerships in transport

Análisis de la influencia de la política nacional y factores económicos en el éxito de la asociación entre los sectores

Patricia Galilea A.1, Francesca Medda2

1 Centre for Transport Studies, University College London. p.galilea@ucl.ac.uk

2 Centre for Transport Studies, University College London. f.medda@ucl.ac.uk

Abstract

Since the emergence of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the 1980s, there has been a structural change in the way countries now finance and provide public infrastructure. Although national governments apparently encourage PPPs, and many have succeeded, some others have failed. Using data from transport sector projects for 72 low- and middle-income countries from the Private Participation in Infrastructure Project Database of the World Bank, we investigate the role of three main factors in the success of these transport PPPs: national experience, the presence of private investors, and the influence of multilateral lenders. The results of the study highlight the importance of the foundation provided by national experience. Not only does national macroeconomic experience appear to have a relevant role, but so also does its past experience (either positive or negative) of transport PPP projects. An interesting finding of the analysis is that the perception of a country’s level of corruption and democratic accountability has significant bearing on the final outcome of a PPP project. Also, the region and subsector of the PPP project seem to play an important role in its success.

Key words: Public-private partnership, corruption, democratic accountability.

Resumen

Desde el surgimiento de la asociación entre los sectores público y privado en la década de 1980, ha habido cambios estructurales en la forma como los países financian y proveen infraestructura pública. Aunque aparentemente los gobiernos apoyan esta asociación y en muchos casos ha Fecha de recepción: 17 de septiembre de 2008 sido exitoso, en otros ha habido fracasos. Utilizando datos de proyectos en el sector transporte de 72 países de ingreso bajo y medio registrados Fecha de aceptación: 22 de enero de 2009 en la base de datos del Banco Mundial sobre la participación de agentes privados en proyectos de infraestructura, los autores investigaron la influencia de los tres principales factores en el éxito de tales proyectos: la experiencia nacional, la presencia de inversionistas privados y la influencia de la banca multilateral. Los resultados del estudio resaltan la importancia de las bases provistas por la experiencia nacional. No obstante, se destaca que la experiencia nacional microeconómica no es el único elemento determinante, sino son igualmente relevantes las experiencias previas (positivas o negativas) de proyectos de transporte con asociación público-privada. Un interesante hallazgo en el análisis es que la percepción del nivel de corrupción del país y la solidez de su democracia son determinantes sobre el resultado final de los proyectos. Además, la región y el subsector del proyecto de asociación también juegan un importante roll sobre su éxito.

Key words: Asociación público privado, corrupción, responsabilidad de mocrótico.

Fecha de recepción: 17 de septiembre de 2008 Fecha de aceptación: 22 de enero de 2009

1. INTRODUCTION

National governments around the world differ substantially in their social and economic structure and in particular in their infrastructure endowment. State governments are characterized by very diverse administrative cultures and capabilities and distinct legal and planning traditions. For instance, institutional diversity in the transport sector is considerable, with countries adopting different approaches with respect to user charges and ownership structures. This should already prepare us for the variety of approaches to infrastructure investment strategy and financing. Despite these differences, a framework for what are now referred to as PPPs (Private Public Partnerships) has emerged to provide transport services through partnerships between three main actors: public sector, private sector and lenders. The main potential benefit of the PPP approach in transport is its flexibility in adapting the structure of incentives and risk-sharing to the features of the project and to the economic and institutional environment. But because of this flexibility, it is perhaps unwise to seek a unique model of PPP that can be replicated across transport sectors and across countries. The choice context is indeed a multi-objective decision, and in practice, the three actors have to achieve a judgment about the trade-offs between the various, sometimes conflicting, objectives.

The literature devotes special attention to the difficulties in PPP agreements between the public and private sector [1-4]. Within this framework, multilateral lenders such as the European Union and the World Bank have openly supported public projects involving PPP agreements between private investors and governments, especially from developing countries (Independent Evaluation Group) [5]. However, private banks are seen as the party that always wins [6] even if the project fails, or if the government and the private company have to renegotiate the PPP. There are several papers examining the behaviour of the private investor, in particular focusing on the maximization of private benefit under incentives schemes [1], [2], [7], [8]. There is clearly a literature gap concerning how certain characteristics of the private sponsors may affect a PPP outcome.

When examining PPP agreements, several authors observe the necessity for a shift in the public sector role: that is, from being merely a provider to increasingly becoming a regulator [5]. This implies the need for a legislative and administrative framework in order to facilitate PPP investments [9]. Although many countries use PPP arrangements, we observe different ways of adopting this approach due to different cultural influences and traditions in planning and management of public works, deficiencies in legal and institutional structures, and different degrees of political awareness and acceptance of the PPP concept. [10] highlight the potential significance of a country’s past experience in PPPs in attracting further PPP projects to that country. However, we observe that there is as yet no empirical evidence showing how this experience may (or may not) affect later PPP outcomes. Also, the connexion between a country’s level of corruption has not been studied in the light of its influence in the success of a transport PPP project. Several studies have been made about corruption and its influence on economic growth [11-17] but none has been conducted in a more microeconomic way.

In light of this observation, the objective of the present paper is to examine how these three actors, public sector, private sector and multilateral lenders, each contributes to the success of PPPs in transport investments, by considering different political and socio-economic contexts. We will also focus our analysis on the effect of a country’s level of corruption and democratic accountability in the success of a PPP project.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents our hypotheses with their theoretical backgrounds. In Section 3 we describe the dataset used to test the hypotheses previously described, outline the dependent and independent variables employed in our analysis, and explain the modelling procedure. Section 4 describes and analyzes our results on the variables that may affect a PPP outcome and thus concludes the paper.

2. HYPOTHESES FORMULATION

In order to address the impact of the three actors on the success of PPPs, in this section we discuss the hypotheses that represent the backbone of our analysis. Although there are many elements which influence the success of PPP agreements, we consider in this analysis three main building blocks: country experience, sponsors and multilateral lenders.

The first block represents the country’s past experience in transport PPPprojects as well as its macroeconomic performance when the project started and the way a country is perceived in terms of corruption and democratic accountability. This block will be the foundation for the success of the project and will (or will not) reinforce the subsequent blocks. We assume that a country with "bad" past experience in PPP projects and/or deficient macroeconomic performance will not attract as many private investors for its PPP projects, as would another country with better experience. The second block is the link between the private investors involved and the PPP project. The private investor might have several characteristics, and in this paper we focus on the number of private sponsors forming the consortium in charge of the PPP project. The final block represents the multilateral lenders supporting the PPP project. Although some of the literature discusses their role as agents of policy change and focuses on how they might add a degree of external coercive pressure to the PPP project’s national government [18], we concentrate on their presence as a means of success for the PPP project.

2.1. Country experience

2.1.1. Country’s past experience with transport PPPs

Past experience in running infrastructure projects related to transport projects may be a good forecaster of future PPP outcomes related to transport. It reflects not only the government’s reputation in its capacity to honour agreements with the private sector, but also the capability of the private sector to accomplish projects with the private sector. This experience has proven to be a critical predictor of successful future PPP arrangements [10]. Positive outcomes and thus country experiences on previous transport PPPs are associated with positive outcomes of future PPPs in that country.

- Hypothesis 1a

Good country experience on previous transport PPP projects is positively associated with the outcome of the next PPP in that country.

Past experience sometimes also implies the existence of unsuccessful PPP projects. This experience, although "bad", might enhance the future chances for successful PPP projects due to the learning process that the negative experience could provide. However, we assume here that having unsuccessful PPP projects means having a black spot on a country’s record of PPP projects, and can therefore potentially discourage future private investments, attract fewer investors, and may also signal to the government or the public sector that they are not coping successfully with PPP projects.

- Hypothesis 1b

Bad country experience on previous transport PPP projects is negatively associated with the outcome of the next PPP in that country.

2.1.2. Country’s macroeconomic performance

The stability of a country, based on its macroeconomic conditions, is important in order to attract private and foreign investors (especially in emerging markets, as shown in [19]), and has also proved to be important in limiting the number of PPPs in a country [10]. We will analyze its effects on the positive outcome of a PPP. Poor macroeconomic conditions may hinder the success of a PPP project, whereas a good macroeconomic performance may foster better outcomes.

- Hypothesis 1c

Satisfactory country macroeconomic conditions are positively related with the chances of successful PPP projects in that country.

2.1.3. Country’s corruption index

Most of the economic literature agrees that corruption would tend to lower economic growth [13-17].1 As pointed out by [17], corruption may reduce economic growth as it lowers the incentive for entrepreneurs to invest. Corruption can also distort the composition of government expenditure, shifting the expenditure of public resources from socially desirable projects to projects where it is easier to extract large bribes. When a country is perceived as corrupt, there might be fewer private investors willing to support projects in that particular country, constraining the set of potential investors (and thus restraining the "optimal" investor for the project). There is also a higher probability that the chosen provider may not be the most capable, but rather the one with the best bribe, thus limiting the likelihood for a successful outcome.

- Hypothesis 1d

The more a country is perceived as corrupted, the less likely it is that the PPP has a positive outcome.

In order to test if the perception of corruption may be more relevant in some regions rather than in others, the interaction between them will also be analyzed.

- Hypothesis 1e

The effect of the perception of corruption on the success of a PPP varies within projects in different regions.

2.1.4. Country’s democratic accountability index

When a developing country is perceived as having low democratic accountability (DA), it means that that country’s government is less responsive to its people. For instance, an autarchy would be perceived as having the lowest DA, whereas an alternating democracy2 would be perceived with the highest. Although it might be the case that a lower number of investors would like to invest in a country with a low DA, once a willing private investor is selected for a PPP project, government support (with all its authority) will follow, and so it is less likely that this PPP will fail. Conversely, a PPP agreement in a country with a high DA will have government support, but it might be subjected to a shift in support due to change unforeseen by means of a democratic vote.

- Hypothesis 1f

The more a country is perceived as having low democratic accountability, the more it is likely that the PPP has a positive outcome.

The influence of the perception of DA may differ among the different types of projects. Projects such as airports, seaports and railroads are more capitalintensive than toll roads, thus they have a higher level of risk. Governments with lower DA will have more authority to assist these types of projects if needed, whereas governments with higher DA will generally not be able to do it.

- Hypothesis 1g

The effect of the perception of democratic accountability varies within different types of projects, thus affecting the final outcome of a PPP project

2.1.5. Country’s region

Countries belonging to certain regions usually share cultural, socioeconomic and political characteristics. They might have a similar rule of law, or they might react the same way to certain situations or problems. There are also regions with more experience in PPP projects than others, as shown in [20]: Latin America and the Caribbean region have received 50 percent (US$345 billion) of worldwide private capital flows to the infrastructure sectors during the 1990s. The implication here is that the region where the project is located can possibly affect the success of a PPP transport project.

- Hypothesis 1h

The region where the project is located affects the outcome of a PPP project.

Different types of projects may have diverse results among the regions, as proven by [20]; they evaluated the profitability of infrastructure concessions in Latin America and found differences among sectors. The experience that a region has in toll roads versus seaports can be dissimilar; and the ways the different societies might welcome certain projects can vary. The interaction between types of projects and interaction among the regions will be analyzed.

- Hypothesis 1i

The region where the project is located, and the type of project affect the outcome of a PPP project.

2.2. Sponsors

2.2.1. Number of private investors

As the number of private investors increases, it might be harder for them to agree and work efficiently; therefore a negative outcome for the PPP project might be more likely if there is more than one private sponsor.

- Hypothesis 2a

If there is more than one private sponsor on a PPP project, it is more likely that the PPP has a negative outcome..

However, the ways the number of sponsors affect countries with different incomes could differ. In countries with low- and lower middle-incomes, more than one private investor in a PPP project could indicate that the consortium has broader expertise and proficiency in PPP projects; they will share part of the costs and risks; and more parties will be watchful of their own (and their partners’) investments. These characteristics may prove to be more relevant in countries with low- and lower middle-incomes, since the country itself might not have the expertise on infrastructure investments. A positive outcome for the PPP project may therefore be more likely with more than one private sponsor in low- and lower middle-income countries.

- Hypothesis 2b

If there is more than one private sponsor on a PPP project, it is more likely that the PPP has a positive outcome in a low- or lower middle-income country.

2.2.2. Private percentage of the project contract or company owned by private sponsors

Ownership is a major factor in the PPP literature, as discussed by [21] and [22], as ownership will provide certain incentives to the private in charge of the PPP project. In every PPP project a project company is in charge of its development, or a project contract stipulates the rights and duties of the private parties. A project company may be owned by a percentage of the private sponsors.3 Whenever private sponsors own a larger share of the project company, they should have a greater incentive to become involved and closely follow the results of the project. Thus when they own a greater share, it is expected that a better outcome can be achieved by the PPP project.

- Hypothesis 2c

Positive PPP outcomes are more likely to occur when the private percentage ownership of the project company (or the project contract) is higher.

2.3. Multilateral lenders

2.3.1. Role of multilateral lenders

Multilateral lenders or lending agencies (the World Bank, European Investment Bank and Asian Development Bank, among others) are sometimes involved in PPP projects by executing their role as the giver of loans. As proven by [23], lending by these agencies stimulates growth in the recipient countries, in some cases. To be sponsored by these multilateral lenders, government and private investors in a PPP project must fulfil several conditions, such as timing of recouping the investment, interest rates and regulation regime. Many lenders monitor the PPP process from its inception, through the selection of the private investor, and to its final development and completion. So if a PPP project is sponsored by a multilateral lender, it will be invigilated, thus the PPP’s failure should be increasingly unlikely.

- Hypothesis 3: Existence of multilateral lenders in a PPP project will enhance the positive outcome of that PPP.

In the next section we will describe the dataset used to test the six hypotheses described; we will explain the modelling procedure and the dependent and independent variables employed in our analysis.

3. METHODS

3.1. Data description

To test the previous hypotheses, a database with 856 transport PPP projects was used. This database is part of the Private Participation in Infrastructure Projects Database, which has projects from four sectors: energy, telecommunications, transport, and water. The original database is a joint product between the World Bank and the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF).4 In order to be included in the database, the project must involve the ownership or operation of physical assets required to provide the infrastructure services, and must have a private sponsor who bears a share of the project’s operational risk. Only 856 projects related with the transport sector are analyzed in this paper. Transport sector projects are divided into four subsectors: toll roads (47%), seaports (29%), airports (13%), and railroads (11%).

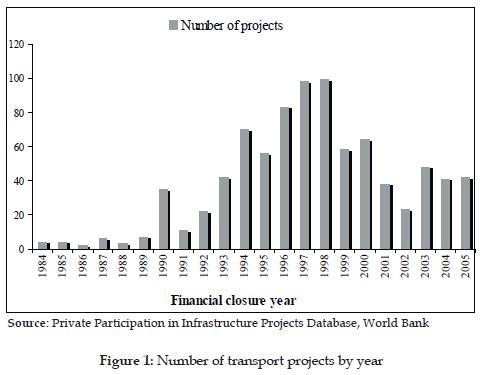

The database provides data for transport projects that reached their financial closure5 between 1984 and 2005. Figure 1 illustrates that almost one-third of the projects reported reached their financial closure between 1996 and 1998. The increase in the number of projects reflected in 1990 is due mainly to the toll roads subsector, whereas the increase until 1998, and the decline since 1999, is reflected in all subsectors.

The database only includes projects awarded in low- and middle- income countries as classified by the [24] World Bank (2005). The transport database covers data from 72 countries, classified in six regions: East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Almost half of the projects (44%) are from Latin America and the Caribbean, dispersed mostly among Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and Chile. The projects from East Asia and the Pacific are highly concentrated in China, while the projects from South Asia are concentrated in India.

Data regarding macroeconomic information for the countries included in the database was collected from the World Economic Outlook of the International Monetary Fund [25](http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2006/02/data/index.aspx)

Data regarding the corruption and democratic accountability index are from PSR Group database.

3.2. Modelling procedure

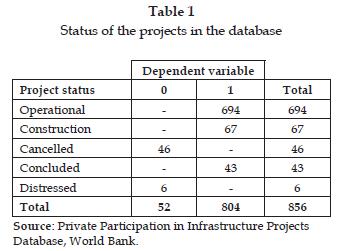

Our dependent variable (Success) is a binary variable, taking the value zero if the project’s status was either cancelled or distressed, and one if the project’s status was under construction, operational or concluded. So in order to estimate the regressions, we use a generalized linear model in the form of a logit model [26].

where γ is the dependent variable, x is the vector of independent variables, and β is the vector of parameters.

3.3. Dependent variable

Each project of the database may be in one of the following five states: i) under construction (projects for which assets are being built); ii) operational (projects that have started providing services to the public); iii) concluded (projects for which the contract period has expired and the project was neither renewed nor extended by either the government or the operator); iv) cancelled (projects from which the private sector has exited before the end stipulated in the contract); and v) distressed (projects where the government or the operator has either requested contract termination or are in international arbitration).

The status of the project was grouped into a dichotomous measure, entitled Success, equal to one if the project’s status was under construction, operational or concluded. In our sample of 856 projects, 804 were in this status (94%). If the project’s status was either cancelled or distressed the dependent variable was set equal to zero. Table 1 illustrates the total status of the projects in the database and their relation with the dependent variable.

3.4. Explanatory variables

Past experience with PPPs. Two variables measuring the past experience of a country in transport PPPs were created, entitled Yes PPP Experience and No PPP Experience, respectively. For a PPP, Yes PPP Experience counts the number of successful6 transport PPP projects done in the PPP’s country at the moment of the PPP’s financial closure; whereas No PPP Experience counts the number of unsuccessful7 transport PPP projects done in the PPP’s country at the moment of the PPP’s financial closure. Both variables are set to zero for countries with no prior experience in transport PPPs. Projects that are done in the same country do not necessarily have the same values in Yes PPP Experience or No PPP Experience, since it depends on the year that each has its financial closure.

Variables that characterize a PPP. A variable representing the total investment (investment in facilities and in government assets) for each project was included (Total Investment). Its values are in 2005 constant US million dollars. It is expected that a project needing more investment will have greater difficulty achieving a positive outcome. Another variable (Percentage private) was set to show the percentage of the project company or project contract owned by private investors. The database projects may belong to one of the following transport sectors: toll roads, seaports, airports, and railroads. One dummy variable was created in order to report the type of sector in which the project belonged: Toll Roads became 1 if the project was a toll road project, 0 otherwise.

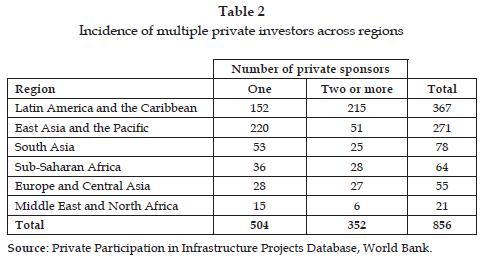

Number of sponsors. The variable (Sponsors) was built in order to capture the effect of the number of private sponsors in a PPP project. Table 2 illustrates the frequency of the consortiums comprised of more than one private sponsor across the different regions. In general, 41% of the total of PPP projects of the database involves more than one private sponsor, but these consortiums are primarily in Latin America and the Caribbean (61%).

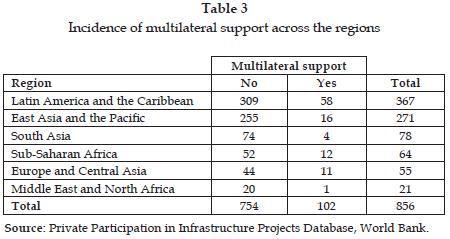

Multilateral lenders. The variable Number of Agencies was constructed to reflect the number of multilateral lenders in certain projects. As shown in Table 3, a multilateral lender supported only 12% of the projects in the database, and 57% of these are projects realized in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Country’s corruption index: A 6-point scale variable Corruption was included for each country for the project’s year of financial closure. The value 6 was given to the most corrupted country as perceived during that year. The types of corruption that the variable takes into account are actual or potential corruption (excessive patronage, nepotism, job reservations, loose ties between politics and business, etc).

Country’s Democratic Accountability: A 6-point scale variable Democratic Accountability was included for each country for the project’s year of financial closure. The higher number of points is assigned if a country is closer to an alternating democracy governance, while the lowest score is assigned to an autarchy.

Country’s Region: Three dummy variables were created to classify the region in which the project was executed. Africa becomes 1 if the project is in the Sub-Sahara Africa region or in the Middle East and North Africa region, 0 otherwise. Asia becomes 1 if the project is in the South Asia region or in the East Asia and Pacific region, 0 otherwise. Latin America becomes 1 if the project is in the Latin America and the Caribbean region, 0 otherwise. Projects executed in the Europe and Central Asia region were taken as the base case and represented when the three dummy variables became 0.

Country’s Income: One dummy variable was created to classify whether by the project’s financial closure the country of the project was a low- or lower middle-income country or an upper middle-income country. Low and Lower Middle Income variable became 1 if the country of the project was a low- or lower middle-income country, 0 otherwise.

Other explanatory variables. A dummy variable to include GDP growth was added (GDP growth). If, during the year of financial closure GDP growth of the project’s country is negative, then the value of this dummy is zero. If GDP growth is between 0% and less than 3% it takes the value one; if it is between 3% and less than 6%, it takes the value two; and it takes the value three if GDP growth is more than or equal to 6%. Another variable was included to measure the country’s development: the current account balance as the percentage of GDP for each project on its year of financial closure (Account). Finally, in order to capture exogenous macroeconomic trends that might be affecting the results, the variable Trend was created, starting at 0 in year 1984, and adding one for each year until 2005.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

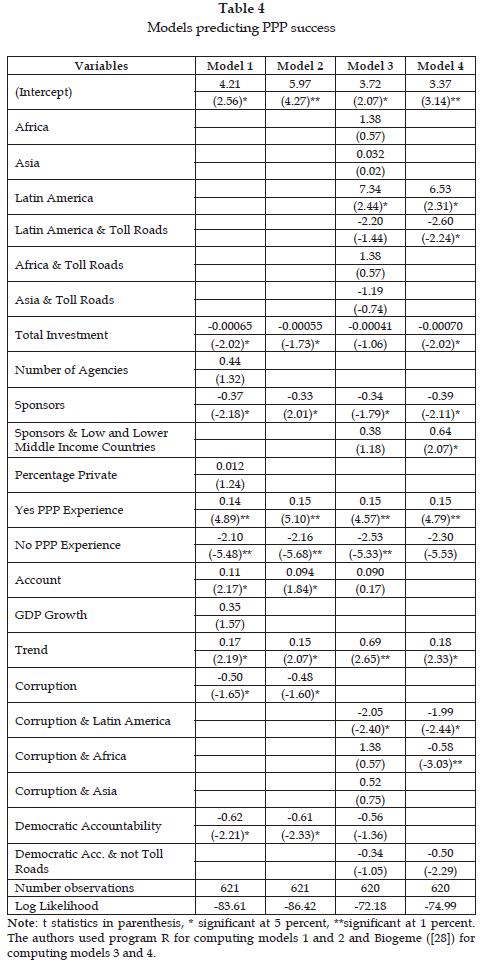

Four models were estimated as shown in Table 4. Model 1 was our first approach in modelling the hypotheses, where we focused on the effect of the variables representing countrys’ past experience with PPPs (Hypotheses 1a and 1b), macroeconomic performance (Hypothesis 1c), corruption (Hypothesis 1d), democratic accountability (Hypothesis 1f), number of sponsors (Hypothesis 2a), and multilateral lenders (Hypothesis 3). As not all the variables were statistically significant at a 95% of confidence, Model 2 was estimated in order to fulfil this requirement. In Model 3 we wanted to upgrade the estimation by including the dummy variables representing the different regions of the world where projects are located (Hypothesis 1h), and the interactions between the former variables used and the regions (Hypothesis 1e), types of projects (Hypotheses 1g and 1i), and the income level of the country (Hypothesis 2b). Model 4 resumes all of the hypotheses and shows those that proved to be statistically significant.

We find strong support for almost all of our hypotheses. In all specifications the variable representing the total investment (in facilities and government assets) proves to be significant. We find statistically-robust support for a negative association between the total investment and the success of a PPP project. This seems likely, as a higher total investment means a riskier project, which in turn makes it increasingly difficult to achieve a successful outcome.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1a, we observe a positive association between a country’s past experience with transport PPP projects and the success of later PPPs. All the models show that the parameter for the variable Yes PPP Experience is statistically significant and positive. This reflects the significance that past experience in transport PPP projects plays in the success of future transport PPP projects. Past experience is not only a learning process, but also highlights a government’s reputation in honouring this type of agreement. In a similar way, Hypothesis 1b is strongly supported by the models, denoting a distinction between good and bad experience (successful and unsuccessful projects), and sanctioning failed past experience in transport PPP projects.

As expected, we also find a positive association between a country’s macroeconomic performance, reflected in the variables Account and GDP Growth, and the positive outcome of a PPP project (Hypothesis 1c). Both models acknowledge the importance of the variable Account. On the other hand, Models 1 and 3 indicate a positive influence of the variable GDP growth in the success of a PPP, but they also show a low significance. The variable account only proved to be significant in Model 3. The macroeconomic conditions on the models suggest the relevance of these indicators in predicting the outcome of a PPP project. While good macroeconomic conditions may enhance the positive outcome of a PPP project, poor macroeconomic conditions may inhibit it.

In the case of the variable related with corruption, there is a negative association between countries perceived as more corrupted and successful PPP projects (Hypothesis 1d). This highlights the difficulties that PPP projects may face in more corrupted countries, where fewer investors are willing to supply a PPP project, thus constraining the optimal outcome of a PPP. Also, even if there are private investors willing to participate in the PPP project, it may be that the selected private partner will be the one with the best bribe or better political relationships, rather than the most capable one. The influence of corruption appears more prevalent in a project’s success if it is executed in Latin America and the Caribbean and Africa (Hypothesis 1e). These regions seem to be more sensitive to the perception of corruption, although the average of the country’s perception of corruption in Latin America is not the highest. This situation might reflect a market threat in countries perceived as corrupted in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Regarding Hypothesis 1f, both models show a strong positive relationship between developing countries perceived with low democratic accountability and PPP outcomes. Considering the countries in our dataset, this relationship highlights that a country with a low democratic accountability score, perhaps an autarchy government, may potentially have more authority to support the PPP project than a more democratic government. These types of infrastructure projects (highways, ports, airports, etc.), which require large sunk investments and a very long recouping period, are often perceived as an improvement by people living in developing countries; and their failure is related with a government’s failure. Therefore, in order to fulfil the requirements of the projects, governments with lower democratic accountability seem more prone to successful PPPs. However, the perception of democratic accountability seems to be more relevant in all transport projects except toll roads, which is in line with the previous justification about the necessity for large capital investments in these types of transport investments.

In order to use the dummy variables for regions (Hypothesis 1h), all the projects in Europe (and Central Asia) were regarded as the benchmark. As shown in Model 4, Asian (South Asia or East Asia and the Pacific), African (and Middle Eastern) and European countries bear the same risk in terms of transport PPP success. Conversely, Latin American (and Caribbean) countries show a lower risk of failure. This could be due to the longer PPP experience that most Latin American countries in the database have compared with other countries in other regions. Although projects from European countries have been more successful (in percentage) than Latin American’s, they are fewer in number and thus their PPP experience is lower.

Turning to the hypotheses regarding sponsors (Hypotheses 2a and 2b), we find enough evidence to support Hypothesis 2a. Variable Sponsors proved to be significant to assert the importance of the number of investors in a transport PPP project. As the number of sponsors increases, the chance of a successful PPP decreases. Larger numbers of private investors that form big conglomerates may have increased difficulty in communication and a higher chance of dispute among them. On the other hand, countries with low- or lower middle-income appear to offset this result as the parameter representing this interaction appears to be positive and significant (Hypothesis 2b). These countries usually have lower expertise in large infrastructure projects (and less in PPP projects), so greater investor expertise might prove to be more relevant than a communication problem. A project in a riskier country represented by a low income status could, moreover, compel private sponsors to remain alert and involved in this particular investment.

Hypotheses 2c and 3 are not statistically validated by the models presented in Table 4. The variable representing the existence of multilateral lenders proves to be statistically insignificant, but its positive sign confirmed at least that the suppositions described previously were in the right direction. To understand these results, a correlation analysis was made and no indication of a correlation arose between these variables and the other ones modelled. Previous results [27] have shown that before introducing such variables as corruption, democratic accountability and regions, these two variables were statistically significant, but their importance lessened and thus lowered their significance. As shown in Table 3, only 12% of the database projects had at least one multilateral lender, so we will continue to analyze their importance as more projects (with more information) become available.

In relation to the models, only Models 1 and 2 focus on the variables describing project and country, whereas Models 3 and 4 use the information provided by the first two models and add the interaction between variables and the region constants. As the log likelihood increases, this information proves to be relevant for the estimation. The best model is Model 4, since it includes more information about the variables and the interactions between them; it is statistically superior than Model 3 (all its parameters are significantly different than zero); and, because a loglikelihood-ratio test does not reject the null hypothesis that both models are equivalent, for parsimony, Model 4 is better.

5. CONCLUSIONS

PPP projects have gained relevance as a way to finance transport infrastructure and services. PPPs have been supported by governments, sponsored by the private sector, and have also been favoured by multilateral agencies. Although there are numerous successful PPP projects, notwithstanding, there have also been a large number of "divorces" [6]. In this paper we have presented empirical evidence on the role that country experience in PPPs, private investors, and multilateral lenders may play in the positive outcome of a PPP in transport.

A country’s past experience in PPP agreements in transport is important, not only in attracting new investment projects, but also in instilling greater confidence in the success of present projects. This also means that countries with poor past experience, or no past at all, will find it more problematical to complete successful PPP projects. However, if multilateral lenders want to promote PPP investments, they should support projects in countries with limited or no experience and help them set up a regulatory and/or legislative framework for PPP projects.

It is not surprising that GDP growth and the current account balance as a percentage of the GDP may impact on the success of a PPP project. Unfortunately, countries that require successful PPPs often have very low (or even negative) GDP growth and a negative account balance. As [10] also highlights, development agencies should assist these countries to pull them out of the underdevelopment trap.

The perception of a country’s level of corruption and democratic accountability appears to be relevant in the final outcome of a PPP project. Countries with governments perceived as corrupted will hardly find international investors (often those with the most experience in this type of project) or even capable ones willing to construct and/or supply the project. Moreover, usually the company selected could be the one with the higher bribe and/or with the best political connection, rather than the most capable one.

On the other hand, projects developed in countries with governments perceived as having low democratic accountability can achieve better performance than projects in countries perceived as having higher democratic accountability. In this case, it seems that autarchies may have a better capacity to assist PPP projects, if needed, than in the case of alternating democracies.

The importance of the region where the project is located has proven to be relevant, making Latin American projects more attractive for success, and thus for future investors. Although European and African projects in the developing world do not have a poor record in terms of their success, they do have less experience in PPP agreements in transport, and this situation could be damaging their score (in relation to Latin American projects). Development agencies should focus on these regions, not only to allow them to grow in terms of experience, but also to help them define a regulatory framework for PPP projects.

A critical point in our research is certainly the definition used for the success of a PPP, since we consider a variable linked with economic performance, rather than use a variable related to the status of a project. Our further research will be directed towards obtaining more precise investment information in order to broaden our results. We will compare the results with a similar analysis of transport PPP projects in the developed world, since certain conclusions, such as the effect of corruption, may be different in this scenario. Also, it would be interesting to study the success of PPPs focusing within one transport subsector, in order to add more specific characteristics and some efficiency indicators into the analysis.

Notas

1 Some authors have pointed out that some level of corruption is desirable [11-12].

2 By alternative democracy we refer to a countryís democracy, where besides having fair and free elections to the executive and legislative powers, and an active presence of more than one political party, there is a viable opposition and the executive power has not served more than two successive terms. In other words, it is a democracy where the same party or coalition has not been continuously in power.

3 The private investor’s ownership may be a percentage of the project contract or project company. This does not necessarily indicate the ownership of the project’s assets.

4 The database can be downloaded at http://ppi.worldbank.org/

5 Financial closure, as defined by the Private Participation in Infrastructure Database, occurs when there is a legally binding commitment of private sponsors to mobilize funding or provide services.

6 Successful is understood as a project whose status was under construction, operational or concluded.

7 Unsuccessful is understood as a project whose status was cancelled or distressed.

REFERENCES

[1] J.-J. Laffont, Incentives and Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

[2] J.-J. Laffont and D. Martimort, The Theory of Incentives-The Principal Agent Model. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2002. [ Links ]

[3] P. Grout, "The Economics of the Private Finance Initiative". Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol 13, no. 4, pp. 53-66, 1997. [ Links ]

[4] O. Hart, "Incomplete Contracts and Public Ownership: Remarks, and an Application to Public-Private Partnerships", The Economic Journal, vol. 113, pp. 69-76, March 2003. [ Links ]

[5] World Bank Independent Evaluation Group, A Decade of Action in Transport. Washington, D.C: The World Bank, 2007. [ Links ]

[6] A. Estache, "PPI Partnerships vs. PPI Divorces in LCDs." World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3470, 2004. [ Links ]

[7] J.-J. Laffont and J. Tirole, A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1993. [ Links ]

[8] D. Martimort and J. Pouyet, "Build It or Not: Normative and Positive Theories of Public-Private Partnerships", Centre for Economic Policy Research, Discussion Paper DP5610, 2006. [ Links ]

[9] F. Medda and G. Carbonaro, "Public-Private Partnerships in Transportation: Some Insights from the European Experience". EIB Working Paper, 2007. [ Links ]

[10] M. Hammami, J.F. Ruhashyankiko and E. Yehoue, "Determinants of Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure", IMF Working Paper WP/06/99, 2006. [ Links ]

[11] N. Leff, "Economic Development through Bureaucratic Corruption", American Behavioral Scientist, pp. 8-14, 1964. [ Links ]

[12] S.P. Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968. [ Links ]

[13] D.J. Gould and J. Amaro-Reyes, "The Effects of Corruption on Administrative Performance". World Bank Staff Working Paper No. 580, 1983. [ Links ]

[14] United Nations , Corruption in Government. New York: United Nations, 1989. [ Links ]

[15] R. Klitgaard, "Gifts and Bribes", in R. Zeckhauser, Strategy and Choice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991. [ Links ]

[16] A. Schleifer and R.W. Vishny, "Corruption" The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 108, no. 3. pp. 599-617, 1993. [ Links ]

[17] P. Mauro, "Corruption and Growth", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 110, no. 3. pp. 681-712, 1995. [ Links ]

[18] W. Henisz, G. Holburn and B. Zelner, "Deinstitutionalization and Institutional Replacement: State-Centered and Neo-liberal in the Global Electricity Supply Industry", Conference paper American Political Science Association Conference, Washington, DC, August 2005. [ Links ]

[19] M. Dailami and M. Klein, "Government Support to Private Infrastructure Projects in Emerging Markets" World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 1868, 1998. [ Links ]

[20] S. Sirtaine, M.E. Pinglo, J.L. Guasch, and V. Foster, "How Profitable are Infrastructure Concessions in Latin America: Empirical Evidence and Regulatory Implications", Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility Trends and Policy Options, no. 2, 2005. [ Links ]

[21] J. Bennett and E. Iossa, "Building and Managing Facilities for Public Services". Journal of Economics 90 pp. 2143-2160, 2006. [ Links ]

[22] T. Valila, "How Expensive are Cost Savings? On the Economics of Public-Private Partnerships", EIB papers, vol. 10 no. 1 pp. 95-119, 2005. [ Links ]

[23] J. Butkiewicz and H. Yanikkaya, "The Effects of IMF and World Bank Lending on Long-Run Economic Growth: An Empirical Analysis", World Development, vol. 33, no. 33, pp. 371-391, 2005. [ Links ]

[24] World Bank, 2005. [ Links ]

[25]Database World Economic Outlook of the International Monetary Fund (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2006/02/data/index.aspx). [ Links ]

[26] W. Greene, Econometric Analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003. [ Links ]

[27] P. Galilea and F. Medda, "Influence of Foreign Private Investors and Multilateral Lenders on the Success of Public-Private Partnerships in Transport", Second International Conference on Funding Transport Infrastructure, Leuven Belgium, 2007. [ Links ]

[28] M. Bierlaire, "BIOGEME: A free package for the estimation of discrete choice models", Proceedings of the 3rd Swiss Transportation Research Conference, Ascona, Switzerland, 2003. [ Links ]