Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Papel Politico

Print version ISSN 0122-4409

Pap.polit. vol.15 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2010

The Eternal Yesterday? The Colombian Reintegration Process as Social Dilemma*

¿El eterno ayer? El dilema social de la reintegración en Colombia

* Review article. This work was able thanks to the generous and helpful attitude of the participants. We are grateful to Professor Gustavo Salazar for his comments. A version of this article was presented at the 68th Annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 22-25, 2010. Chicago, Illinois. Panel: The lasting impact of political and economic legacies.

** Politólogo, profesor de la Facultad de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Director del Semillero de Investigación sobre Conducta Humana y Ciencia Política. Contacto: a.casas@javeriana.edu.co, andrescasas.blogspot.com

*** Politóloga de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: guzman@javeriana.edu.co, juanitaguzman03@hotmail.com. Pertenece al Semillero de Investigación sobre Conducta Humana y Ciencia Política.

Recibido: 30/09/09 Aprobado evaluador interno: 30/02/10 Aprobado evaluador externo: 01/03/10

Resumen

Este artículo busca sugerir respuestas para algunas preguntas relativas a la relación entre transición hacia la paz, dilemas sociales y cultura política democrática. Hacemos énfasis en que para cualquier ser humano, tanto la desmovilización como la reintegración constituyen pasos que implican dejar atrás las formas de acción e interacción propias de la guerra. En particular, supone aprender nuevas formas de resolución de problemas -modelos mentales- por medio de mecanismos no violentos. Sugerimos que la fase de reintegración es un proceso gradual que implica el abandono de la preferencia por los atajos de la violencia y de la ilegalidad, dados los incentivos que incrementen la probabilidad de ocurrencia de los beneficios para resolver dilemas sociales a favor del bien público -convivencia pacífica y democrática. Desarrollamos nuestro argumento de la siguiente manera: establecemos la relación entre desmovilización, cultura política y democracia; explicamos la lógica de la reintegración desde una perspectiva analítica y los hallazgos de la investigación; interpretamos el mecanismo de reintegración como un dilema social; desarrollamos un modelo formal de reintegración como dilema social para identificar las tensiones propias al fenómeno. Por último, ofrecemos algunas reflexiones y retos producto de esta investigación.

Palabras clave autor: Modelos mentales, desmovilización, reintegración, dilema de la reintegración, acción colectiva, cultura política.

Palabras clave descriptor: Desmovilización, cultura política, dilemas éticos, acción comunitaria, Colombia.

Abstract

This work suggests answers to some key questions concerning the relationship between transition to peace, social dilemmas and democratic political culture. We emphasize the fact that for any human being, both demobilization and reintegration are steps that involve leaving behind the forms of action and interactions of war. In particular, these processes involve learning new ways of solving shared problems (mental models) through nonviolent mechanisms. We suggest that the reintegration phase is a marginal and incremental process that involves the abandonment of the preference for 'shortcut' behavior such as violence and illegality, given the incentives that increase the likelihood of benefits to solve social dilemmas in terms of the public good (peaceful and democratic coexistence). We develop our argument as follows: We establish the relationship between demobilization, political culture and democracy, explaining the logic of reintegration from an analytical perspective and research findings; then we interpret the mechanism as a social dilemma and develop an approach to reintegration that helps identify some of the tensions expressed in this process. Finally, we offer some thoughts and challenges that arise from this work.

Key words author: Mental Models, Demobilization, Reintegration, Reintegration Dilemma, Collective Action, Political Culture.

Key words plus: Demobilization, Political Culture, Ethical problems, Community action, Colombia.

Motivation

what is left behind when a combatant exits war? What is the weight of the past when faced with the possibility of change? What is at stake in the transit from being a combatant to become citizen? How can the mindset of war, that characterized a past state of the world, be transformed when uncertainty remains the rule in the new state of things? What kind of deal is required, and what implicit and underlying conditions are necessary to guarantee an effective demobilization process? Is the transit from fighters to citizens possible without a full macropolitical transition from war to peace? What are the odds of a transition from war to peace without the transit of non-democratic forms of social relation to the exercise of a real democracy at the micropolitical level? What is the meaning of democracy as an alternative mental model to war? Is the current Colombian reintegration processes producing positive effects on production of democracy in the micro and macro level in Colombia? What can we expect of the current process of demobilization and reintegration in this particular case?

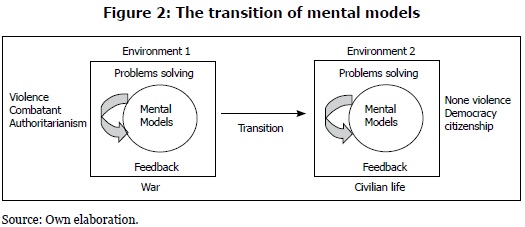

This work suggests some answers to some of these questions, emphasizing that for any human being this step involves leaving behind the forms of action and interaction inherent to war; in particular, it involves learning and adopting alternative problem solving strategies (mental models) through non-violent mechanisms, in order to fulfill an ideal setting in which the rule of law prevails, democratic and participative channels are available for dispute resolution, there is a reduction of uncertainty about the future and self regulatory mechanisms operate in order to help guarantee peaceful coexistence and the legitimacy of formal institutions in synchronic relationship with informal norms.

We suggest that the reintegration phase is a long-term process. It is also an incremental change process that involves the abandonment of the preference for 'shortcut behavior', such as violence and illegality, given the incentives that increase the likelihood of benefits to solve social dilemmas in favor of the 'public good' (peaceful and democratic coexistence.) This clearly does not depend exclusively on the programs designed by a given government, but is also determined by the contexts and by individual and local particularities. Therefore, attention from disciplines such as political science on this type of processes can help explore mechanisms to generate iterative dynamics that can turn on alarms and analyze alternatives to redirect actions and procedures in order to attain the goal of peace building. Social sciences can help overcome the dangers of the eternal yesterday effect, which involves the great challenge of 'reintegrating' the minds and hearts of citizens in the transition from war to peace. This means demobilizing all forms of interaction and organization marked by authoritarianism as well as demobilizing violent means of solving interaction problems related with coordination, cooperation, conflict and distribution, at a local level.

1. Social change, demobilization and reintegration

In Prosperity and Violence, Professor Robert Bates (2001) uses the concept of "eternal yesterday" to refer to the weight of the past in developing societies. Mantzavinos, North and Shariq (2004) returned to the concept of 'path dependency' to extend it to three types: cognitive past dependency, institutional path dependency, and economic path dependency. This extension of the concept is explained by the authors' belief that in order to understand a society, one must understand the weight of the past in its present relationships. However, the burden of the past does not occur at a single level, it has particular effects in a multidimensional sense. In their introduction to cognitive institutionalism, Mantzavinos, North and Shariq (2004) suggest that far from being a purely exogenous phenomenon, institutional change occurs in people's minds (North, 2005). North suggests the importance of taking into account variables that affect mental structures, specially, shared mental models that individuals, groups and societies develop to solve problems of coordination, cooperation, conflict and distribution.1

In a previous research experience2 we explored the burden that the past -expressed as beliefs molded by experiences- may have in the present, in terms of the actual behavior of individuals, and the effects of the past on their idea of the future. This question involves not only demobilized individuals but also the host communities in the process of reintegration. In order to conduct a field research to understand some aspects related to the demobilization and reintegration process, in 2008 we selected the Ciudadela Santa Rosa, a marginal neighborhood settled in the periphery of Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia. We selected that particular community given its high level of reception of demobilized population from different armed groups, including guerrillas and paramilitary organizations. We built an analytical framework that could allow us to characterize the political culture of the demobilized population and also explore the prospects for the deepening of democracy at the local level with reference to the ongoing demobilization process.3

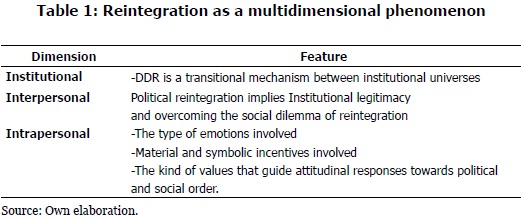

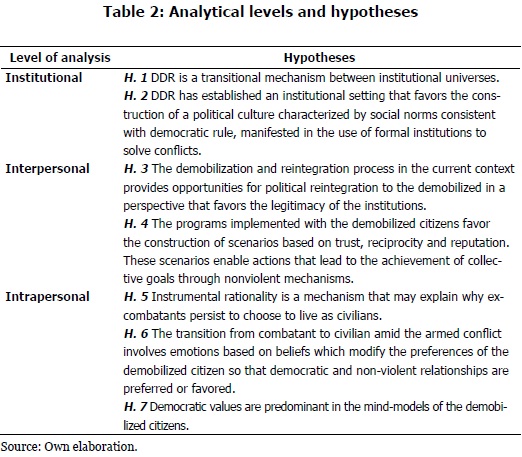

As mentioned above, to test our hypotheses we chose to build an analytical framework that could account for the multidimensionality of the phenomenon of demobilization. In order to solve this problem, we relied on the contributions of cognitive institutionalism developed by Mantzavinos (2001); Mantzavinos, North and Shariq (2004) and North (2005), as well as on the political culture approach developed by Almond and Verba (1963), Fuchs ( 2007), and the Theory of Cultural Change developed by Inglehart (1997). We also followed insights from Elster (2007), Petersen (2007) and Ostrom (2007), in particular on their reflections on motivations of human action, emotions and social dilemmas, respectively.

Our analysis was focused on the demobilized. Our aim was to explore the features and effects of the process on three dimensions of human experience proposed by Casas (2008), the intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional dimensions, and to identify the mechanisms operating in each one of them. We also wanted to characterize the political culture of the demobilized and explore the prospects for the deepening of democracy in Colombia at the local level with reference to the current demobilization process. In other words, we wanted to verify if there was any sign of change in the mental models of the demobilized as well as in those of the members of the host communities.

With the aim of furthering the understanding of some key issues involved in transitions to peace, we felt it was necessary to develop systematic approaches that can offer explanations about the decision-making processes of actors and their interactions at the micropolitical level. On issues related to the Colombian conflict, Arjona and Kalyvas (2007:200) argue that there have been studies that have helped advance descriptive and explanatory aspects, such as the expansion of groups and local forms of violence. However, there are still large amounts of key questions to be addressed from a micropolitical perspective.

In sum, our work offers some elements that can help characterize the effect of demobilization and reintegration in the minds of the demobilized, in order to deepen the prospects for the legitimacy of formal institutions in Colombia, and non-violent and democratic forms of coexistence. The product of our research is divided into five main sections. In the first section we define the problem in order to determine whether the institutional framework adopted for demobilization and reintegration in Colombia has permeated the political culture of the demobilized, so as to promote the quality of democracy; or if on the contrary, there is a parallel coexistence of the institutional universes of war and peace. This section also presents some hypotheses and methodological issues. The second section deals with the theoretical aspects of political culture and mental models. We provide some theoretical and conceptual elements necessary to enable us to argue: that political culture can be understood as a mental model that consolidates and affects the three dimensions of human experience formerly outlined. It focuses on the institutional dimension, arguing that Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) is a transition mechanism between two institutional universes.

The third section, addresses reintegration from a political and analytical point of view. The central argument of this section is that reintegration can be better understood as a political phenomenon in terms of a social dilemma. The fourth section addresses the intrapersonal aspects of the demobilized in Santa Rosa, making reference to human motivations and values that prevail in the minds of the demobilized. It concludes by referring to shortcut behavior as the prevailing feature of interaction in the political culture repertoire of the demobilized.

In general, we want to share our findings in relation to the four objectives of the study:

- To establish the relationship between demobilization, political culture and democracy.

- To explain the logic of reintegration from an analytical perspective and from research findings.

- To interpret the mechanism of reintegration as a social dilemma, that is, as a mass collective action problem.

- To outline an ideographic model of reintegration as a social dilemma to identify the tensions inherent to the phenomenon.

Finally, in the fifth section we provide some thoughts and discuss some challenges posed by our findings.

2. Transition to peace, political culture and democracy

The Colombian conflict has developed within a State that defines itself as democratic, participative, and as a guarantor of a fair social and political order (See preamble to the Constitution of 1991). However, the study on the Political Culture of Democracy in Colombia developed by LAPOP4 (2008), shows that Colombia ranks as "the country with the highest proportion of citizens in the category known as authoritarian stability. In fact, 38% of Colombians express high levels of support to the system, but low levels of political tolerance "(LAPOP, 2008:30). The concept of authoritarian stability means that while about 70% of Colombians show high levels of support for the political system, which speaks well of legitimacy, most people surveyed show intolerance when it comes to the rights of minorities (LAPOP, 2008:30). This data indicates the fragility of democracy in Colombia in the long term (ibid. 195). It is also disturbing to consider that this type of system may tend to move toward an authoritarian (oligarchic) system in which democratic rights would be restricted (ibid. 194).

From this perspective, the political culture of Colombian citizens shows worrying signs. For example, Colombia is the country where people more strongly believe that a minority should be prevented from opposing the decisions of 'the people', and one of the first in which citizens are convinced that those who are not with the majority, represent a threat to the country (ibid: 31). Colombian population also ranks second among those who believe that the president must govern without Congress and ignore the decisions of the High Courts, and one of the countries with the highest proportion of citizens who believe that the president could, in certain circumstances, close, dissolve Congress or the Constitutional Court (ibid.: 31).

This suggests that Colombian democracy is far from being a consolidated democracy as defined by Juan Linz and Alfred Stephan (1997, 1997:15):

- Attitudinally, democracy becomes the only game accepted: even when faced with important political and economic crisis, the vast majority of citizens believe that any future political opportunity must occur within the parameters of democratic procedure.

From this perspective, democracy cannot be consolidated in the absence of a democratic political culture that ensures the emotional and cognitive support for adhering to democratic procedures (Linz. J, Stephan. A. 1997:15). This idea addresses the first assumption of this article: the existence of democratic scenarios is related to attitudes, values, beliefs, desires and emotions that guide the behavior of citizens. Unfortunately, Colombian democracy is continually being challenged by the persistence of various forms of informal conflict resolution through non-democratic and violent mechanisms (see Cante, Mockus, et al, 2005).

Societies, like human beings, are living organisms that learn and adapt to different contexts over time, through problem solving processes (Mantzavinos, 2001). Societies may change by accident, evolution or intentional design. From this perspective, it is the relationship between organisms and institutions which enables changes in the institutional setting (North 2003: 18). Returning to North (2003) the second assumption of this work relates to institutional design as a tool which makes social change possible.

From the perspective of institutions, institutionalism argues that:

- Whatever the perspective or the type of government, the relevance of institutions lies in that they are the principal means to structure democracy, the political system, and especially, our political practices, behaviors, rules, norms, routines, codes and of course the processes of socialization, participation and social and political interaction. (Rivas, 2003:37).

The Colombian Government, like others in societies that suffer internal armed conflicts, has adopted various mechanisms to diminish the war and move towards the consolidation of democracy and peace. The central concern is how to create peace agreements in the long term, and especially, how to achieve the reintegration of former combatants into civilian life. The Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) programs have become a central component of the contemporary toolbox of transitions to peace. As mentioned by Rodriguez (2007:21) these programs should guarantee an institutional mechanism that allows the transition of combatants into civilian life. These programs according to Theidon (2007), involve multiple transitions: from fighters who surrender their weapons to governments that seek to cease an armed conflict; to communities that receive or reject the demobilized. Additionally, these transitions involve complex dynamics that cover the demands for peace and justice (Theidon, 2007:67).

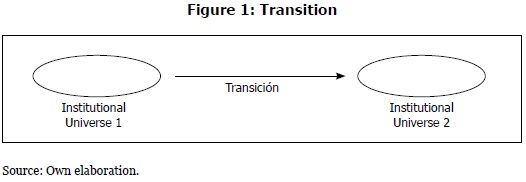

From a neo-institutional perspective, demobilization involves a transition between institutional universes, one in which there is a shift from the appropriation and application of the rules of war and the armed organization, to the appropriation and application of the rules defined and enforced by the State. Each institutional universe implies a way of structuring human interactions and solve problems that go hand in hand with attitudes, beliefs, preferences and emotions towards political order (Rodríguez 2007:19); or in terms of Easton (1953:13), towards the strict allocation of values in a given community. Human interactions within an institutional universe, form a system of beliefs, emotions, preferences and attitudes, which are modified by the experiences of individuals, changing their behavior according to the resolution of problems. This means that DDR effectiveness depends on changes in the behavioral repertoires to facilitate problem solving in civilian life (Rodríguez 2007:21).

According to Romero (2007:100), the literature has identified four contextual variables that threaten the success of the return to civilian life: "The first relates to the persistence of armed rebel groups; the second is associated with the availability of resources or income from illegal drug trafficking, with which armed groups can be financed; the third has to do with the existence of an illegal market of guns, and the fourth is related to the lack of control of territory by the State" (CNRR, 2007: 100).

In Colombia, each of these variables is present in greater or lesser extent. As Theidon and Romero stated, this conditions determine that the reintegration phase becomes one of the weakest links of the DDR process. Most demobilization processes in the world are carried out as a result of negotiation and the signing of a peace agreement, accompanied by the ceasefire. However, the Colombian case differs from these experiences for two reasons: First, although the agreement was negotiated with most of the paramilitary organizations, there were no formal agreements with other armed groups (ELN, FARC, etc.). In the current scenario we cannot speak of a collective peace process and negotiations that culminated in the signing of an inclusive peace agreement with long-term prospects. Secondly, because the demobilization has been a top-down process that was initiated by the national government and that has been crystallized by formal institutions, i.e. by laws and executive decisions. In particular, Alvaro Uribe's government, designed the 975 of 2005 Law, also called Justice and Peace Law, as the formal institutional mechanism to facilitate the transition of members of armed groups into civilian life, as well as serve as transitional justice mechanism.

The issue that brings up this work is whether the institutional framework adopted for the demobilization and reintegration in Colombia has permeated the political culture of the demobilized, so as to promote the quality of democracy in Colombia; or in the contrary, there is a parallel coexistence of the institutional universes of war and peace in the minds of the demobilized at the expense of building democratic scenarios. As stated by Rodríguez (2007), situations such as internal armed conflicts, the presence of illegal economies or forced acculturation processes give path to institutional realities that are defined in opposition to the established institutions, but co-exist within the same borders (Rodríguez 2007:19).

3. The logic of reintegration from an analytical perspective.

An analytical perspective of reintegration involves three assumptions:

- First, a transition between institutional universes that activates transitional mechanisms.

- Second, reintegration is a decisional phenomenon that implies a social dilemma.

- Third, reintegration is a multidimensional phenomenon, which affects simultaneously intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional levels of human experience.

It also means constructing hypotheses distortion level that would allow some prejudices and insights on the subject:5

3.1. Institutional dimension

In recent years, Colombia has experienced the demobilization of armed groups in the middle of an ongoing armed conflict. The current demobilization process is, from a quantitative perspective, the biggest since the 1990 decade (see CNRR 2007:105).

As we stated above, from a neo-institutional perspective, demobilization involves a transition between institutional universes. From one in which there is an appropriation and application of the rules of war and the armed organization, to another where the appropriation and application of the rules are defined and enforced by the State. Each institutional universe implies a way of structuring human interactions and solving problems that go hand in hand with attitudes, beliefs, preferences and emotions towards political order (Rodriguez 2007:19); or in terms of Easton (1953:13), towards the strict allocation of values in a given community.

Human interactions within an institutional universe form a system of beliefs, preferences, emotions and attitudes that are maintained or changed by the experiences of individuals, changing their behavior according to the resolution of problems. As mentioned by Rodríguez (2006), the transit from one universe to another involves new information, adapting to new sets of opportunities, changing beliefs and learning new ways to solve problems (Rodríguez 2006:1).

Following Rodríguez (2006):

- The concept of transition can adequately express the idea in the sense that etymologically it comes from the Latin "trans" or "Transitio" meaning beyond, from one side to another, through, or the fact that a change has been completed (Gómez 2003:687), and the Latin "Itionem" which means action, process, result, condition or effect (ibid. 2003: 358). Transition is then the action of moving from one place to another. (Rodriguez 2007:20).

North (1990) suggests that institutional change occurs in peoples' minds. From this perspective, it is essential to explore the cognitive consequences that occur throughout the reintegration process. It is also necessary to explore the process of transition to peace from the point of view of the shared mental models that shape the political culture of the demobilized.

3.1.1. DDR as a transitional mechanism

DDR is a transitional legal instrument that was developed due to the increasing numbers of internal armed conflicts. After the end of the World War II, it applied to fighters of the army and state officials that were bound to return to civil life. Given the rise of unconventional warfare, including civil wars and internal armed conflicts, DDR focused on the rebels or revolutionary groups who shared the same borders of the stately organizations they were fighting against. DDR focuses on the mechanisms to enable excombatants from rebel groups to return to civilian life and comply with the institutional frameworks that they rejected during war (ibid. 2007).

DDR involves all the actions undertaken by states which suffer the effects of internal armed conflicts, oriented to the demobilization, disarmament and transition to civilian life of former combatants, with the help of international organizations, civil society and donor countries.

DDR is considered one of the most important steps in a peace process. Sustainable long-term peace achievements depend on a successful DDR process (Naraghi, Pampell 2004:1). From this perspective, by disabling the mechanisms of violence and reintegrating former combatants positively, DDR can generate conditions for development which facilitate peace keeping. Its aim is to create alternatives to violence so that former combatants do not disrupt the efforts of a peace process while waiting for a sustainable reintegration and return to productive civilian life (Theidon, 2007).

DDR can be understood as a transitional mechanism because it allows combatants to disarm and enter the realm of civility, democracy and peace. We suggest that DDR contributes to achieving a lasting peace process where those involved directly in the conflict can break with the past. The transition, as mentioned by Rodríguez (2007), involves a shift from a set of rules (formal and informal rules of the armed organization) to another, expressed by the normative boundaries defined by the State (legal organization) (Rodríguez 2007: 19).

Transition from war to peace implies the pressure for a change in mental models expressed in attitudes, beliefs, values, and emotions. The demobilized confront the challenge of adapting to a new set of rules, while testing new solutions to problems and establishing individual and shared mental models in the new scenario. In this sense, civil life means learning new ways of relating with others and new ways of solving problems.

Within the DDR programs, the component of reintegration is the transitional phase that focuses specifically on breaking with the past, in the transition to a new situation (Elster 2007).

As mentioned by Rodríguez (2007):

- "This involves the recomposition of society through shared responsibility among all its members, so that people that are about to enter legal standards, are accepted and have equitable access to full political and social rights. This implies the recognition and respect for the particularities of each individual. "(Rodríguez 2007, 27).

Traditional approaches to DDR have focused almost exclusively on military and security elements. Therefore, these programs have been developed in isolation from the field of transitional justice and its concern for historical clarification of events, justice, reparations and reconciliation (Sundh, L; Schjolien J. 2006). By reducing DDR programs to dismantle the war machine, their chance of failing rises, because they do not necessarily consider how to demobilize combatants and facilitate the reconstruction of social networks and local collective coexistence. The traditional approach of DDR is not sufficient to ensure effective reintegration, as it has failed for not having given sufficient consideration to crucial aspects concerning the host community, and for not having considered local cultures or gender conceptions that increase the probability of rehabilitation and reintegration (Theidon, 2007: 89).

The spirit that should encourage societies that are willing to build a lasting peace, requires transcending violence and the alleviation of its urgent demands, and implies a qualitative change in society (Acosta et al. 2007:35)

In this regard, it is not just a rehabilitation process by which veterans internalize rules and skills that enable them to live in society as "reintegrated" (Acosta et al. 2007: 35). It must be conceived as a process of simultaneous transformation of the victims and former combatants and the social contexts, so as to enable an eventual "reintegration" of society as a whole (Acosta et al. 2007).

According to research by Theidon (2007): "Most of the former fighters reported to be looking for some way to leave war behind, and now live that desire in the midst of limited economic options and an ongoing armed conflict. Unfortunately the country remains highly militarized as men and women are constantly recycled in the war. The irony? Many of these fighters are subject to a transition, but the social context is not." (Theidon 2007: 77).

DDR must be therefore accompanied by programs with a logh-term vision and appropriate linkages between DDR programs and transitional justice initiatives. By placing DDR within the framework of transitional justice, policy makers and officials can help strengthen the reintegration phase of former combatants into civilian life, which has been the weak link in the chain of DDR (Theidon 2007 : 67).

3.1.2. Evidence

Given the data collected through the interviews with former combatants in Santa Rosa, we found that our first hypothesis holds in the sense that:

H. 1 DDR is a transitional mechanism between institutional universes.

We can affirm that DDR can be understood as a transitional mechanism because it allows fighters to disarm and enter the realm of civility, democracy and peace building. The nature of the DDR is to contribute to achieving a lasting peace process where those directly involved in the conflict break with the past and come to live within society. The transition, as mentioned by Rodriguez (2007), involves passing from a set of rules (in the armed organization) to another, expressed in the borders defined by the state regulations (legal organization) (Rodríguez 2007: 19).

Transition means a change in mental models and involves changing attitudes, beliefs, values, and even emotions. The demobilized should assume the challenge of adapting to a new set of opportunities within civility, which changes the way to perceive reality while testing new solutions to problems and establishing individual and shared mental models in the new scenario. In this sense, civilian life means learning new ways of relating with others and new ways of solving problems.

H. 2 DDR has established an institutional setting that favors the construction of a political culture characterized by social norms consistent with democratic rule, manifested in the use of formal institutions to solve conflicts.

This hypothesis is rejected by the evidence found. The interviewees, both, demobilized and members of the community, privilege taking the law into their hands instead of resorting to the authorities. In both groups there is mistrust in the ability of formal institutions to solve problems, so it is better to solve them by one's own hand. This poses a dilemma between the legal regulation and the social regulation. Not to resort to the authorities has become a culturally accepted rule. This is aggravated by the perception of official inefficiency that justifies not sanctioning individuals who decide to take justice in their own hands.

There are several questions worth rising. Why do not opinions among the demobilized population and the members of the host community differ radically when asked about the dilemmas related to conflict resolution? Moreover, ¿why is this so given that the host community has not gone through the institutional universe of the armed group?

3.2. Interpersonal dimension

The second dimension refers to the interpersonal interaction in which people develop problem solving strategies. In this sense, the selection among interaction strategies of actors depends on the interplay between mental models and action situations, whether these situations demand cooperational or conflictual responses (Casas, 2008:86). From this perspective we explore: (1) what the status of the reintegration phase is in a political sense; and (2) we want to check if the implemented reintegration programs foster the building of scenarios based on trust, reciprocity and reputation, which allow individuals and communities to perform actions that can help the achievement of collective goals in a non-violent manner. The assumption is that relationships based on trust, reputation and reciprocity can facilitate collective action and promote the reintegration of demobilized combatants.

3.2.1. What is reintegration?

According to the United Nations, reintegration refers to "...the processes by which ex-combatants acquire civilian status and gain sustainable employment and income. Reintegration is essentially a social and economic process with an open time-frame, primarily taking place in communities at the local level. It is part of the general development of a country and a national responsibility, and often necessitates long-term external assistance...".6

It is important to highlight that reintegration is directly related to the peaceful coexistence and to social 'reconciliation' processes that could in no way be imposed in top-down manner. It is an interdependent and dynamic development requiring the cooperation of the entire social group to thrive (Croll, 2003: 50). This view makes long-term results of reintegration the most important factor for stability and peace.

In other words, the success of demobilization programs can be evaluated in terms of whether the deomobilization contributed to peace building, and if the former combatants have been successfully reintegrated into civilian life. The reintegration process begins once the ex-combatants have been demobilized and resettled with their families in the place where they want to start a new life. The reintegration process is not homogeneous. It is the complex result of thousands of micro stories with individual and group efforts, with setbacks and successes. Every ex-combatant and family group must build a new way of life and reconcile with society (Croll 2003: 50).

3.2.2. Types of reintegration

Most of the literature addressing the issue agrees on studying reintegration through three dimensions: social, economic and psychological. Social reintegration is a process by which the ex-combatants and their families feel they are a part of society and are accepted by the community. Economic reintegration is the process whereby the homes of the demobilized restore their livelihoods through production and / or other types of gainful employment. As for the psychological aspect, reintegration focuses on learning new ways of relating in civility leaving behind the legacy of military indoctrination. The ex-combatants go through a personal process of adjusting attitudes and expectations after losing a predictable environment and a certain social prestige (Croll 2003: 50).

While reintegration is a social process, it is the ex-combatants who bear the greatest burden of the process. Therefore reintegration programs offer first humanitarian aid in basic needs and resettlement (Croll 2003: 50). The lack of reintegration support may jeopardize peace building. Some veterans may return to illegal groups or recycle the violent practices in the new place where they are, i.e. they can start forming gangs, be employed as mercenaries, assassins etc., thus reproducing the logic of war (Croll 2003: 50).

Therefore, social, economic and psychological reintegration of individuals and groups that were once involved in war is defined by all the processes associated with the reintegration and social and economic stabilization of children and adults voluntarily demobilized, individually or collectively (Acosta et al. 2007:34). These processes must provide a particular way of linking these people to the community that acts as a host for them. Also they must provide mechanisms for the active participation and shared responsibility of society as a whole in the process of inclusion in the civil and legal life of the country (Acosta et al. 2007: 35).

A DDR process must not only advance in terms of integral restitution of rights to former combatants, but also in terms of their perception as active political subjects that are able to materialize the principles of reconciliation and inclusion, human rights and shared responsibility for the gradual construction of the peace process (Acosta et al. 2007:36).

Following Gutiérrez (2004) in his critic approach to the economic explanations of war, materialistic motivations are not sufficient to explain the entry and permanence of individuals in armed groups. Moreover, organizations have powerful processing systems aimed at transforming the individual preferences of the recruits (Gutierrez 2004:60).

- "As Kaldor said, it is not possible to formulate strict economic calculations when people are risking their lives every day. The value of your life for yourself is unlimited (...). So to convince people to risk their lives, armed organizations must promote forms of loyalty and cooperation that allow the relaxation of the individualistic perspective, a common characteristic of all stable armies (common point between Machiavelli, Clausewitz, Napoleon, and virtually all classical thinkers of war.) To consider individual fighters introduces serious collective action problems and creates uncertainty in terms of the utility function of the combatants. The fighters understand that if their partners do not have a minimum basis of gregarious norms, they can be shot in the back. To preserve my fundamental individual interests, I would be better off if someone warned me and my teammates that we should not be too individualistic, a typical solution to the iterated prisoner's dilemma. Only in this case cooperation is guaranteed by existing organizational structures, and not by spontaneous evolution. Leaders face collective action problems and try to solve them with ideas, socialization through organizational routines and common standards" (Gutierrez 2004:61).

In this sense, reintegration from an individual's point of view implies the challenge of adopting rules and ways of relationship as an individual and citizen. Reintegration should aim to integrate individuals with society not only economically, socially and psychologically, but also from the perspective of citizens who participate and legitimize the political aspects of their town, city and country.

3.2.3. Political reintegration

As it has been discussed above, in the literature about DDR programs, reintegration has been addressed in its economic, sociological and psychological dimensions. However, with the exception of Acosta et al. (2007) and Rodríguez (2007), there has been little reference to the reintegration process of former combatants from a political perspective.

So, why is it important to consider reintegration from a political perspective? Shepsle and Boncheck (1997) proposed a vision of politics which includes two different dimensions: capital "P" Politics and small "p" politics. The first one refers to the traditional view of David Easton as "the strict allocation of values in society" (Easton, 1953: 13) and the second, involves a greater spectrum considering the relationships that permeate all political processes in society, with particular emphasis on the so-called informal institutions. These types of institutions, in contrast with formal institutions, are developed in the micro-political arena rather than in the macro-political arena (Mendez, 2008:18).

From this perspective, reintegration affects both the micro and the macro political dimensions. At a micro-political level, reintegration involves scrutinizing the informal institutions or shared mental models which emerge in communities once the demobilization process has been made. This means that the transition from being active combatants to becoming civilians is accompanied by the adoption of new shared mental models as problem-solving mechanisms used in their relationships with others.

At a macro-political level, reintegration is closely related to the acquisition of a new status: a combatant becomes a citizen. Citizenship status in a contemporary sense is "a reference to a set of rights, to a source of legitimacy and to an elusive entity which no one can appropriate or have privileged knowledge of" (Cheresky, Quiroga, Villavicencio and Vermeren, 2001:157).

Citizenship does not only entail having legal and political rights, as was usually held in the past; it also entails adding value to the exercise of democratic participation (Garay, 2000). Cortina (1997) defines citizenship as a two-way relationship between the individual and the community, a relationship which guarantees the individual those rights recognized as legitimate by the community and which demands of him permanent and loyal adherence to them (Mendez 2008:25).

Reintegration from a political perspective, means addressing the problem of legitimacy of formal institutions. The demobilized come from an institutional environment characterized by a denial of Colombia's formal institutions. Thus, political reintegration implies that the demobilized know and accept the formal authoritative allocation of values in Colombia and learn to relate to others and interact in the society within the legal framework.

Following what has been suggested above; political reintegration can be viewed in two dimensions, the macro and the micro political dimensions. From a macro-political perspective, reintegration can be understood as inclusive democratic participation which is derived from the citizen status. And from a micro political perspective, reintegration can mean giving way to an informal institutionality which allows the demobilized to live peacefully with others. Living peacefuy, means coming to live together with different people without the risks of violence and with the expectation of positively taking advantage of the differences among people (Mockus, 2002:20). The challenge of living together in a new community is basically the challenge of tolerating diversity which finds its fullest expression in the absence of violence (Mockus, 2002:20). Living together means abiding by common rules, having culturally entrenched self-regulatory social mechanisms, showing respect for diversity and rules ... it also means learning to undertake, comply and fulfill agreements (Mockus, 2002:20).

3.2.4 The demobilized citizens in Santa Rosa facing legitimacy of Colombian institutions and citizenship

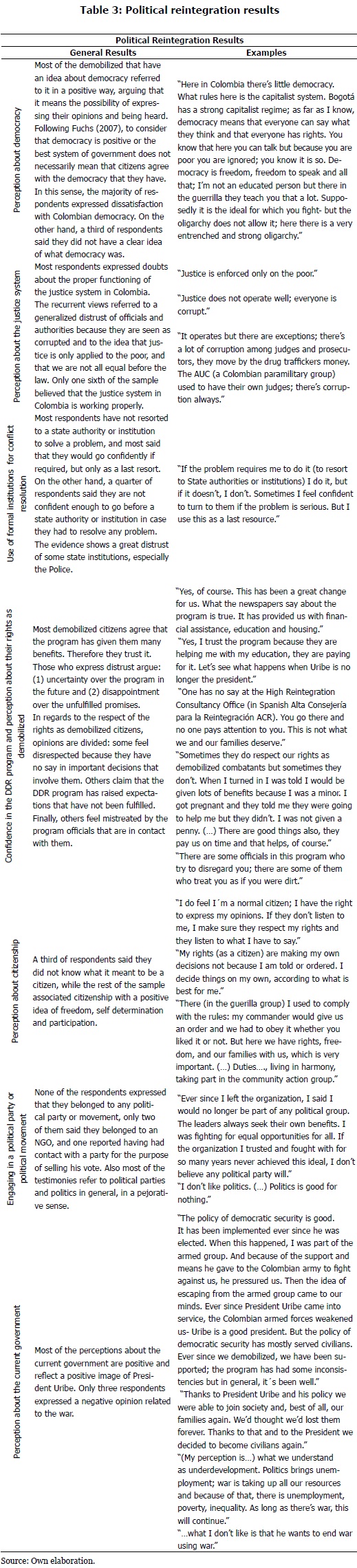

With the aim of furthering our understanding of the political reintegration process at Ciudadela Santa Rosa, the interviews addressed the following aspects: (1) the perceptions of the demobilized about democracy, (2) their perceptions about the justice system, (3) the use of formal institutions in the resolution of conflicts, (4) their confidence in the demobilization program, (5) their perceptions of citizenship, (6) their engagement in any political party or movement, and (7) their perceptions about the current government. Table 3 shows the results.

These findings allow us to conclude the following:

H. 3 The demobilization and reintegration processes in the current context provide opportunities for political reintegration to the demobilized in a perspective that favors the legitimacy of the institutions.

In general, the legitimacy of institutions is questioned by the demobilized citizens in Santa Rosa. Therefore, this hypothesis is rejected. While there is acceptance of democracy, there is no satisfaction with the one they have. In addition, their doubts regarding the effectiveness of the justice system show their distrust in it. Everything related to politics has a pejorative sense, and state officials are referenced as corrupt. Confidence in the program is based on a utilitarian interest, "I am confident because I get benefits." Furthermore, President Uribe is widely accepted as the benefactor. Phrases like "thanks to him" appear repeatedly in the interviews. What is interesting, and at the same time worrying, is that the demobilized believe that the benefits obtained through the program are due to President Uribe. That is why the demobilized, when asked about trust in the program, respond with a great uncertainty about what will happen when President Uribe's administration finishes.

3.3. Intrapersonal dimension

In Guzman (2009) the intrapersonal level was addressed through human motivations for action, identifying aspects that trigger the rational mechanism in the demobilized citizens and some of the emotions that arise in the reintegration phase. This paper identified different perceptions which give us an idea of the underlying values of both, the non-combatant members of the community and the demobilized citizens. According to the data obtained, we can conclude that the possibility of education is definitely an aspect of the program which impacts the perception of future benefits among the demobilized citizens. Regarding emotions, the interviews revealed that almost all respondents are comfortable with and happy about joining the program, but remember the past with sadness for the friends and relatives left behind in the armed organization.

Regarding values, it is interesting to note that the non-combatant community members fit better the traditional values -as explained by Inglehart- than the demobilized. In issues such as abortion, the demobilized citizens are inclined to rational values more than the community members. However, in issues such as tolerance to particular groups, such as homosexuals, the data shows that the ex-combatants are more inclined towards traditional values. Regarding gender equality, the demobilized citizens favor a traditional scheme, whereas the community tends to sound self-expressive values. As for the education of their children, the demobilized citizens favor the rational secular values, contrary to the trend for traditional values in the community. These findings suggest that further research should be done in this area, to reach more conclusive results.

H. 5 Instrumental rationality is a mechanism that may explain why ex-combatants persist to choose to live as civilians.

The interviews show that the possibility of furthering their education is an aspect of the program that can activate rationality. The demobilized perceive they can obtain benefits in the future through studying.

H.6 The transition from combatant to civilian amid the armed conflict involves emotions based on beliefs which modify the preferences of the demobilized citizen so that democratic and non-violent relationships are preferred or favored.

This hypothesis is partially confirmed. Most demobilized citizens remember their time in the organization with sadness because of the social networks they had built there; however, they feel at ease in their current status. Fear of being found and executed appears in some interviews; however the majority of them feel at ease. From an emotional point of view, we can conclude that the demobilized citizens interviewed in Santa Rosa would not like to participate in the armed conflict anymore, although it is unclear whether they favor democratic and non-violent interaction.

H.7 Democratic values are valued in the mind-models of the demobilized citizens.

The data gathered is not conclusive enough to determine which values are held by and are predominant for the demobilized citizens. Further research has to be done in this direction.

4. Reintegration as social dilemma

Considering the complexities which the process of demobilization in Colombia now entails, both the demobilized and the host community face the challenge of peacefully sharing the same locations, social space and the challenge of learning to live together overcoming their mutual mistrust, and establishing reciprocal relationships. Demobilized citizens have to come and live in a completely different and unknown city and community because it is impossible for them to return to their places of origin. They have to start building new relationships which will allow them to live in a non-violent way in the new community. On the other hand, the host communities have to build new relationships with their new neighbors as well, neighbors who unfortunately have held a life marked by violence in the past. Reintegration then has to be viewed not only in a parametric sense, which is from the perspective of the demobilized citizens, but also as a strategic situation between the demobilized citizens and society.

Reintegration from this perspective generates a social dilemma which involves a situation whereby society and the demobilized citizens must face a problem of collective action to make living in peace possible. According to Ostrom (2007:186), a social dilemma refers to a scenario in which individuals select a course of action in interdependent situations; in this scenario, each individual selects his strategies based on the assessment of maximum material benefit he can get in the short run. However this maximizing of individual material benefits does not always lead to the best collective results, thus generating stability with suboptimal results.7 The reason why these situations are dilemmas is that at least another result can render better outcomes to all the participants (Ostrom 2007:186). Therefore, the question which arises is how can we collectively avoid the temptation to maximize individual benefits in the short run so that we all can maximize collective benefits in the long run? (Ostrom 2007: 187).

Reintegration, taken as a social dilemma, implies a problem of collective action. These problems arise and are about public or collective goods and resources for common use (common pool resources). Ostrom (2000) explains that these two types of goods have certain characteristics in common, one of them being the high costs payed when potential beneficiaries are excluded. However, they differ in the subtraction principle. This principle refers to the problem of high demand (overcrowding) and overuse of common resources because the consumption that an agent makes of a certain good affects the consumption of others (see Ostrom 2000:69). This phenomenon does not occur with pure public goods. For example, if security is the public good at stake in the dilemma of reintegration, the consumption that an agent makes of public security should not reduce the general level of security available for the community (Ostrom 2000: 69).

According to Cante (2007), collective action is a strategic interaction process that requires moral, political or ideological agreement (non-dissidence, indifference or apathy) and rational cooperation (not free-riding) among the individual members of a community. Furthermore, collective action depends on beliefs and endogenous and exogenous opportunities (Cante 2007:151). This implies that collective action is not just a problem related exclusively to Homo economicus.

Cante (2007: 155) suggests that processes of strategic interaction and collective action involve at least three interdependencies: a) the agreement (and cooperation) of each individual depends on decisions made by all; b) the agreement (and cooperation) of each individual depends on the agreement (and cooperation) of all; and c) the decision of an individual depends on everyone's decision (Cante 2007: 155).

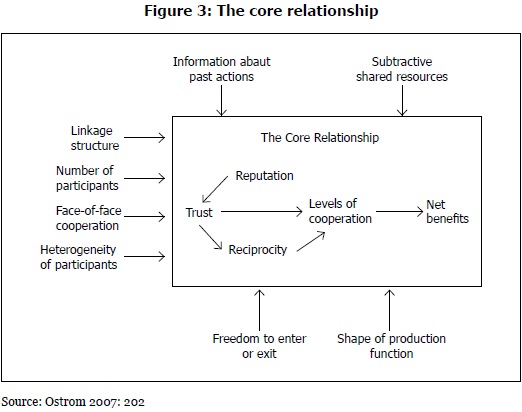

Ostrom (2007:201) suggests that in order to overcome the suboptimal result that characterizes social dilemmas, it is necessary to undertake collective actions focused on relationships based on trust, reciprocity and reputation.

Figure 3 shows the way in which these variables intervene in the generation of positive results at a collective level. It may well be that exogenous variables may affect the results, but Ostrom (2007:201) suggests that the key relations in the generation of collective actions are the three components mentioned above.

Following Ostrom (2007:201), those relationships marked by confidence, reputation and reciprocity can explain success or failure of collective action. In the following section, these relationships will be discussed focusing on the community where the demobilized citizens were established, with the aim of determining whether the perspectives for reintegration of the demobilized are favored or not, thus overcoming the social dilemma reintegration represents.

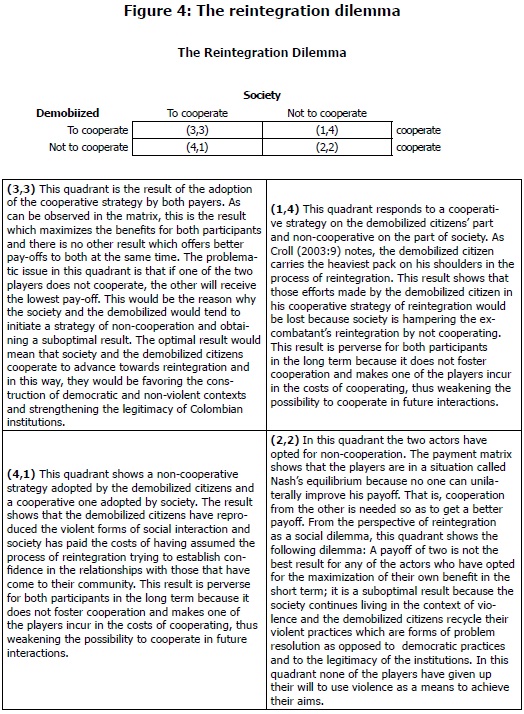

4.1. The dilemma of reintegration

This section discusses a reintegration game, taking the classical version of the prisoner's dilemma as a basis (see Axelrod 1984). A non-sequential simultaneous game is considered, because reintegration is explored under a local perspective, that is, from the interdependency relationship resulting from the moment the demobilized actor enters the community in a given neighborhood and starts interacting with his neighbors. In this type of game, actors' responses are characterized by a non-futuristic vision and the maximization of personal benefits.

Which is the interdependency situation?

The Colombian society - as well as any other society that has suffered the effects of internal armed conflicts and has decided to initiate a transition process towards peace has had to face all the tensions arising from the ideals of justice and peace (see Casas & Herrera, 2008; Sundh, L; Schjolien J. 2006; Theidon 2007; UN/OSAA 2007). In the case of Colombia, this entails having to assume relative levels of impunity with the aim of reintegrating the ex-combatants and advancing towards the consolidation of a democratic, non-violent coexistence. Reintegration is presented as a situation of interdependence because it implies cooperation and consent (in Cante's terms 2007) of the demobilized and also of the society to learn to live with those who have participated in the conflict. This is why this situation is presented as a problem of collective action.

What does cooperation mean?

In this situation, to cooperate means to accept the establishment of relationships based on trust among the demobilized and the society through a non-violent interaction in democratic contexts, so as to legitimize Colombian formal institutions. In other words, to cooperate implies that no player will use violence for private means. According to Putnam (1993:171), confidence is defined as "an essential component of the social capital [...] confidence fosters co-operation. The higher the level of confidence within a community, the greater the probability of co-operation". Furthermore, cooperation demands a long-term vision from the agents in order to gain a collective benefit. Cooperating is by no means an easy task because both the society and the demobilized citizens have their own reasons for not trusting each other. For example, both actors feel threatened by the "contexts of illegality".

Furthermore, cooperation implies accepting the costs of carrying out a process of DDR and transitional justice. Society, for example, has to accept the economic and legal benefits that have to be given to the demobilized citizens. It also implies starting and taking part in a process of reparation and reconciliation through transactions, within a transitional justice framework. On the other hand, the demobilized citizen has to assume the costs of leaving back a predictable context and facing a new institutional scenario. This means that he has to undertake a learning process that will allow him to learn new ways of earning a living in the first place, and to learn how to relate to his new community.

What does non cooperation mean?

Non cooperation means to establish relationships based on uncertainty in contexts where violent relationships that are characteristic of armed conflict context prevail and where interpersonal relationships are based not on democratic processes but on forms of authoritarianism. Non cooperation also implies that the agents have a short term vision and seek the maximization of their immediate individual benefit. Ostrom (2007:194) identifies a third source of action called 'exit option', an alternative where the player can decide to enter or exit the game. This course of action is not a possibility in the dilemma of reintegration offered because its result is non cooperation. For example, if the demobilized decides to go back to war or continue committing crimes, his strategy can be taken as non-cooperative as it opposes the goal of security and the establishment of non-violent relationships within a democratic framework. If society decides to exit the game, this means it is not assuming the costs of reintegration and would not of course be cooperating.

Why is non-cooperation the dominant strategy?

In formal terms, the dominant strategy is non-cooperation because no matter what the other player does, for any of the players the non-cooperative strategy will render better payoffs. Let us imagine for the moment that the demobilized citizen is doing his strategic planning; if society cooperates, the demobilized citizen will obtain a payoff of 3 if he opts for a cooperative strategy. But he will get 4 if he opts for non-cooperation. That is, if society cooperates, it is better for him not to cooperate. Now let us see what happens when society does not cooperate. In this situation, the demobilized will get a payoff of 1 if he decides to cooperate, and 2 if he decides not to cooperate. Here again, the non-cooperation strategy gives better payoffs to the demobilized citizen. The same thing happens to society. This is why the dominant strategy is non-cooperation. This situation leads to a suboptimal equilibrium. The Nash equilibrium, represented in quadrant (2,2) is the situation where none of the players can, on their own, make their situation better. In this particular case in order to change this sort of equilibrium, perverse for both society and the demobilized citizens, the two players need to come to an agreement to move forward to an optimal situation represented in quadrant (3,3).

In real terms, for both players it would be better not to assume the costs of reintegration, that is, to opt for a non-cooperative strategy. In problem resolution circumstances, the use of violence is, indeed, a perverse but effective mechanism. In the same way, democratic scenarios make decision making processes take longer than authoritarian ones. As a conclusion, reintegration implies a problem of collective action which requires cooperation from both actors so as not to become a social dilemma in which the demobilized and the society coexist in violent and non-democratic contexts.

4.2 Santa Rosa and the Reintegration Dilemma

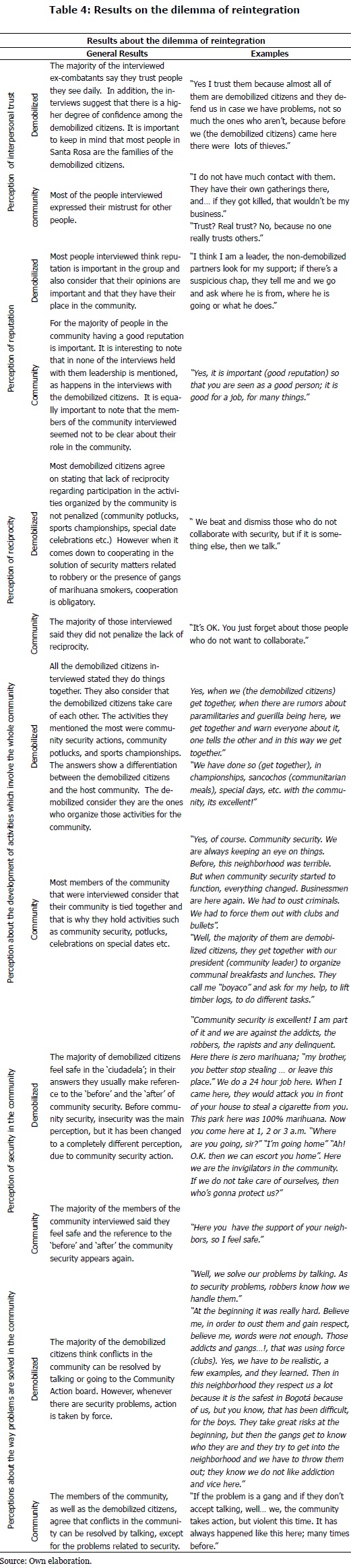

To provide empirical support to the dilemma explained above, the following aspects were researched with members of the host community as well as with the demobilized citizens: 1) Conditions of success in the collective action: (a) perception of interpersonal confidence, (b) perception of the importance of reputation and (c) perception of reciprocity in the community. 2) Perception about the development of activities which involve the whole community. 3) The public good which involves the dilemma: the perception of security in the community. 4) The existence of violent mechanisms in the resolution of problems: perceptions about the way problems are solved in the community. Table 4 shows the results.

When we applied the analytical instruments, we found the following facts:

H.4 The programs implemented for the demobilized citizens favor the construction of scenarios based on trust, reciprocity and reputation which make it possible to accomplish actions leading to the achievement of collective goals through non-violent mechanisms.

In terms of the proposed problem of collective action where the public good that is sought is security, the community of Santa Rosa has managed to achieve a climate of security. From this perspective one may suppose the dilemma has been resolved having attained an optimal result for the participants. However, even if the expected good has been obtained, the interviews reveal the persistence of violent forms of solution to problems. This indicates that an optimal result was generated in terms of the public good wanted, but sub-optimal and perverse in terms of the dilemma of reintegration. In other words, there has been no advancement in the construction of non-violent collective scenarios that may legitimate the country's institutions. In these terms, H.4 is rejected.

The demobilized citizens come from an institutional scenario characterized by absence of State governance so that when they become civilians they must enter a new institutional scenario structured by the formal laws of the Colombian State. However, the locations where the demobilized arrive at are not characterized by having a great deal of State presence and by the lack of preference for authorities and legal institutions as a means to conflict resolution. Therefore, the host community, burdened with the violence generated by different gangs finds a solution to their problems with the arrival of the demobilized citizens. The community and the demobilized citizens align their preferences in such a way that through the efficient mechanism of use of violence or threat to use it, security is provided. The military training of the demobilized citizens is useful for the community in order to provide safety and the community responds positively to this.

This case demonstrates that the logic of the small security agencies parallel to the State does not change or cease through the process of demobilization. So we arrive again at Theidon's thesis (2007) which contends that the demobilized citizens can be individuals that undergo a transition process, not so the society. In terms of cognitive neoinstitutionalism, formal transition institutions are created, but the informal institutions do not undergo any transition.

5. Final remarks

Keeping in mind that the phase of reintegration is a long-term process which depends not only on the programs but on the contexts and the particularities of communities and individuals as well, it is imperative that disciplines such as political science take care of the perspectives of the process to produce an iterative dynamics that will switch on alarms and reorient the process when needed, with the aim of building true and lasting peace.

DDR in Colombia has been one of those processes where greater amounts of money have been invested and where failure in the phase of reintegration would translate into serious social and human cost. As acknowledged in MAPP/OEA report (9 February, 2009:2) it is imperative to give this process of reintegration a closer look. It is time to leave aside the statistics about demobilized citizens and reinserted ex-combatants and start counting the number of ex-combatants that lead a proper autonomous, nonviolent life and whose strategies of solving their problems coincide with a democratic and legitimate scenario from the point of view of the State's institutions.

Political culture understood as a shared mental model is based on the dimensions of the discussed human experiences. In the following remarks, some conclusions at the level of interpersonal analysis will be presented. This level dealt with the concept of political reintegration to characterize the demobilized as a political subject. It also presented reintegration as a social dilemma. In this order of ideas, the conclusion is that the legitimacy of the institutions is, in general terms, questioned by the demobilized citizens in Santa Rosa. While there is acceptance of democracy, there is dissatisfaction with the existing one. Their doubts about the effectiveness of the judicial system clearly show their feeling, namely distrust. Furthermore, the confidence in the program is based on an utilitarian interest: "I trust the program because I can get some benefits."

On the other hand, there is great acceptance of President Uribe as the personal responsible character and as a benefactor. Comments as "thanks to him" repeatedly appear in the interviews. The most interesting, but at the same time most worrying thing, is that the demobilized citizens consider that the benefits they get through the program are due to Uribe. That is why when they are asked about their degree of trust in the program, they are uncertain about what will happen when he is no longer in service.

Regarding reintegration, we can conclude that a suboptimal situation of equilibrium has been attained. This is because it has been possible to establish a safe environment in the community; however, the mechanism used is violence, or at least the threat to use it. This is the reason why the modus operandi of private protective agencies trying to secure safety for people does not cease with their transition to civilian life. Finally, the legitimacy of the State institutions coexists with parallel institutional universes.

The findings of this work suggest that one of the weaknesses of reintegration in Colombia is the possibility demobilized citizens have of creating parallel institutional universes, characterized by the use of violence in the resolution of problems. In other words, the political culture of the demobilized citizens seems to be characterized by "short cuts". "Shortcuts are those short, tempting, easy highways, which because they are quick, make it possible for any person or group to get what they want" (Mockus y Cante, 2002:141).

The proverb "the end justifies the means" is a classic motto for 'shortcut' culture. As shown in this study, in order to attain security, understood as a desired public good, both the host community and the demobilized citizens accept and resort to violence as a shortcut where the benefits of future costs are brought to present value at a high rate of interest thus devaluating or disregarding the future consequences of that action (Mockus and Cante 2002:150). Following Mockus and Cante (2002), this problematic situation has its origins in a society that will not be viable if it continues willingly or unwillingly tolerating shortcuts.

The use of shortcuts is an example of the distance between normative perceptions and pragmatic needs; the majority of the people interviewed responded in a politically correct fashion to issues such as the way of solving problems in the community. However, when it came down to relevant aspects of their lives, such as security, the incentive for shortcuts such as 'violence' appeared.

In terms of social capital, understood as the organization created by social networks (Mockus and Cante 2002:156), it was possible to identify perverse social capital in the process of reintegration when various forms of short cuts were allowed and honored. The perverse nature of the social capital generated lies in the fact that there is social organization around destructive social preferences such as the use of violence, extortive types of relationship, and emotions such as fear.

Unfortunately, in terms of the reintegration dilemma presented here and following Linz and Stephan's conceptualization (1997) about a consolidated democracy, in Colombia, from the point of view of attitudes, democracy is not the sole game accepted. Both society and demobilized citizens are willing to use short cuts to get their goals.

The political reintegration of the ex-combatants must be a priority issue in the peace agenda in Colombia. These pages leave many unanswered questions; however, the lesson is that societies are made up by human beings whose minds are not tabula rasa. It is in this sense that the impact of any program oriented towards social change must take into account the aspects mentioned above, as an alternative to keeping a fall back into an eternal yesterday, characterized by the persistence of mental models that favor violence, authoritarian forms of relationship and illegality.

Pie de página

1For insights on cognitive institutionalism see Mantzavinos (2001), Mantzavinos, North and Shariq (2004); North and Denzau, and North (2005). The cognitive institutionalism argument results incomplete for authors such as Alejandro Portes (2005).2Guzmán Gómez, J. (2009) El dilema social de la reintegración: ¿Una dinámica que conduce a la profundización de la democracia en Colombia? Facultad de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Bogotá. Dir. Andrés Casas-Casas.

3Even though there has been several demobilization processes, the individual demobilization process started during President Alvaro Uribe's first government in 2003. Collective demobilization started in 2005 thanks to the Justice and Peace Law. According to official data from 2003 until August 2009, 51.992 ex-combatants have started the DDR processes.

4The study focuses on political legitimacy and analyzes both the support given to the political system and the political tolerance as combined indicators of democratic stability.

5This article presents some results of the analysis and systematization of the interviews carried out with demobilized and community members in Ciudadela Santa Rosa. Even though the sample is not representative of the demobilized population in Bogotá, it is an important source of information which makes it possible to gain further understanding of the situation to identify features and tendencies in the process of reintegration. We thank the participants that made this research possible, given the security and social difficulties that their participation in this project might have generated.

6United Nations General Secretary. Available at: http://www.unddr.org/iddrs/01/

7A suboptimal result happens when the players guided by their rationality chose a course of action that maximizes their personal benefits, but doesn't represent the best payoff for all the players (see Ostrom 2007: 186).

Bibliography references

Acosta, (2007) "Experiencias de jóvenes excombatientes en proceso de reintegración a la vida civil en Bogotá D.C.". Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. [ Links ]

Almond, G.; Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [ Links ]

Amnesty International. (2005) 'The Paramilitaries in Medellín: Demobilization or Legalization?' AI Index: AMR 23/019/2005, September. [ Links ]

Arjona, A.; Kalyvas, S. (2007). "Reclutamiento de combatientes en Colombia: Resultados preliminares de una encuesta a combatientes desmovilizados". Bogotá: Ed. Vicepresidencia de la república de Colombia. [ Links ]

Bates, R. (2001) Prosperity and Violence. New York. W.W. Norton and Co. [ Links ]

Blondel, J. (2007). About Institutions Mainly, But Not Exclusively Political. En The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions. Oxford University Press. 716-730. [ Links ]

Bocchi, D. (2006). "Proceso de desmovilización de los grupos paramilitares en Colombia. Apoyo de la cooperación europea". Plataforma de Organizaciones de desarrollo europeas en Colombia. Cuadernos de cooperación y desarrollo. Bogotá: Ed. Kimpres Ltda. [ Links ]

Boix, C.; Stokes, S. (2003). Endogenous democratization. En World Politics, 55:517-49. [ Links ]

Cante, F. (2007). "Acción colectiva, metapreferencias y emociones". Cuad. Econ., July/ Dec. 2007. 26 (47).151-174. ISSN 0121-4772. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, J., A. (2005). "Los Parias de la Guerra. Análisis del Proceso de Desmovilización Individual". Bogotá: Aurora. [ Links ]

Casas, A. (2008). ¿Cambiando mentes? La educación para la paz en perspectiva analítica. En Salamanca (coord). Las prácticas de la resolución de conflictos en América Latina. Deusto publicaciones. 83-117. [ Links ]

Collier. P.; Hoeffler. A. (2004). Greed and Grievance in Civil War. Oxford: Economic Papers, 56: 563-95. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Reparación y Reconciliación (CNRR). (2007). "Plan de acción 2007-2008". Acceso: mayo de 2009. Disponible en: http://www.cnrr.org.co/ [ Links ]

Croll, P. (2003). Voces y Opciones del Desarme: Enseñanzas Adquiridas de la Experiencia de Bonn Internacional Center for Conversion, BICC, en otros países. En: Documento N. 49. Ediciones Uniandes. [ Links ]

Dalton, R.; Klingemann, H. (2007). Citizens and Political Behavior. En Dalton y Klingemann (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford University Press. 3-21. [ Links ]

Easton, D. (1969). Esquema para el análisis político. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu. [ Links ]

Elster, J. (2007). Explaining social behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Elster, J. (1997). Egonomics. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Elster, J. (2006). La formación de preferencias en la justicia transicional. En Mockus, A. y Cante, F. (comps). Acción colectiva, racionalidad y compromisos previos. Unibiblios. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Fuchs, D. (2007). The political culture paradigm. En Dalton y Klingemann, (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford University Press. 161-183. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. (2003). Paz por Medios Pacíficos: Paz y Conflicto, Desarrollo y Civilización. Bilbao: Gernika Gogoratuz. [ Links ]

Geddes, B. (2007). What causes democratization?. En: Boix y Stokes (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. 317-339. [ Links ]

Gómez de Sílva, G. (2003). Breve Diccionario Etimológico de la Lengua Española. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica. 687. [ Links ]

Gutierrez, F. (2004). "Criminales y rebeldes: una discusión de la economía política del conflicto armado desde el caso colombiano". En, Estudios Políticos. No. 24 (enero-junio). Medellín. [ Links ]

Guzmán, J. (2009). El dilema social de la reintegración: ¿una dinámica que conduce a la profundización de la democracia en Colombia? Monografía de grado. Director: Andrés Casas. Bogotá. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Hardin, R. (1997). "Economic Theories of the State". En Mueller, D. (ed.) Perspectives in Public Choice. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hinich, M. y Munger, M. (2003). La teoría analítica de la Política. Barcelona: Ed. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. (2007). Mass Beliefs and Democratic Institutions. En The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. 297-316. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and Postmodernization Cultural, Económic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R. (2007). Postmaterialist values and the shift from survival to self-expression values. En Dalton y Klingemann (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford University Press. 223-240. [ Links ]

Instituto de estudios avanzados en cultura. (Acceso: noviembre de 2008). Disponible en: http://www.virginia.edu./iasc/surveys.html. [ Links ]

Kalyvas, S. (2007). Civil Wars. En Boix y Stokes (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. 416-434. [ Links ]

Keefer, S; Knack, S. (2008). Social capital, Social Norms and the New Institutional Economics. En Ménard (ed). Handbook of new institutional economics. Springer. Berlín. 701-725. [ Links ]

LAPOP. (2008). Cultura Política de la Democracia en Colombia: 2008. Vanderbuilt. [ Links ]

Linz, J.; Stepan, A. (1997). Toward a Consolidated Democracies. En Dianomd, Plattner, Chu y Tien (eds). Consolidating the Third Wave Democracies: Themes and Perspectives. John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Losada, R.; Casas, A. (2009). Enfoques para el Análisis Político. Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Losada, R.; Castro, A. (2006). El colombiano en Política. En Nuestra Identidad. Estudio colombiano de valores. Bogotá: Raddar. S.A. T. 2. 27-50. [ Links ]

Mantzavinos, C.; North, D. y Shariq, S. (2004). "Learning institutions, and economic performance". Perspectives on Politics. 2 (1): 75 - 84. [ Links ]

Mantzavinos, C. (2001). Individuals, Institutions and Markets. New York (s.d.). [ Links ]

Mendez, N. (2008). ¿La educación para la paz un mecanismo de cultura política? una aproximación desde el caso aulas en paz. Monografía de grado. Director: Andrés Casas. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Mendoza, D; Guevara. D; Guzmán. J. (2008) Política, Mercados e Instituciones: Un Abordaje desde el neo-institucionalismo cognitivo. Versión sin publicar. [ Links ]

Mockus, A, y Cante, F. (2005). "Superando la guerra y otros atajos" en Acción política no-violenta, una opción para Colombia. Universidad del Rosario. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Mockus, A. (2009). Armonizar ley, moral y cultura. Acceso: abril de 2009. Disponible en: http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=362225. [ Links ]

Mockus, A. (2002). Convivencia como armonización entre ley, moral y cultura. En Perspectivas. XXXII (1). [ Links ]

Naraghi, S.; Pampell, C. (2004). Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration. En: Inclusive Security, Sustainable Peace: A Toolkit for Advocary and Action. International Alert y Women waging Peace. [ Links ]