Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Papel Politico

versión impresa ISSN 0122-4409

Pap.polit. vol.18 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2013

Changing Weather: China's Role in Latin America's Climate Change Policy*

Clima cambiante: el papel de China en la política de cambio climático de América Latina

Ralf J. Leiteritz*

* Type of article: Scientific Research. This paper is a result of the ongoing research project "Política Exterior Latinoamericana, ¿Made in China?: Análisis del impacto del acercamiento económico de China a Brasil y Chile en la formulación de sus políticas exteriores y en sus relaciones con Estados Unidos, 2000-2010" at the Center for Political and International Studies (CEPI) at the Universidad del Rosario. Previous findings were presented at the Second Congress of International Relations held in Mendoza, Argentina, in June 2012. The author wishes to thank Maria Paz Berger and Liliana Galvis for valuable research and editorial assistance.

** Ralf J. Leiteritz is an Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations and a researcher at the Center for Political and International Studies at the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá. E-mail: ralf.leiteritz@urosario.edu.co.

Recibido: 28/11/2012, Aprobado evaluador interno: 07/12/2012, Aprobado evaluador externo: 18/01/2013

Resumen

El artículo trata el problema de si -en línea con el acercamiento económico de China hacia América Latina durante la última década- la región ha experimentado cambios políticos en términos de la política exterior de sus respectivos países, cambiando su alineamiento tradicional con las posiciones del hegemón regional, Estados Unidos. Teniendo en cuenta este enfoque general, el proyecto de investigación se centra en evaluar un tema específico de la gobernanza global: la política del cambio climático. Aquí, encontré una diferencia marcada entre la posición china y la estadounidense, que constituyen dos polos opuestos entre los que deben operar los países latinoamericanos. Tuve en cuenta dos países en términos de ubicación discursiva entre China y Estados Unidos en materia de la política sobre el cambio climático: Brasil y Chile. Logré identificar cambios discursivos durante esa década que sugieren una alineación política de los dos países latinoamericanos con China.

Palabras clave: China, Estados Unidos, América Latina, cambio climático, política exterior.

Palabras clave descriptor: Cambio climático, política exterior, China-aspectos económicos, China, Estados Unidos, América Latina.

Abstract

The paper addresses the issue of whether - in line with the Chinese economic approximation to Latin America during the last decade - the region has experienced political changes in terms of countries' foreign policies, shifting their traditional alignment with the positions of the regional hegemon, the United States. Given this general focus, the research project focuses on evaluating a specific issue of global governance: climate change policy. Here I find a marked difference between the Chinese and the US position, constituting two opposing poles between which Latin American countries must operate. I consider the cases of two countries, Brazil and Chile, in terms of their discursive location between China and the United States on global climate change policy. I was able to identify discursive changes throughout the decade that suggest a political alignment of the two Latin American countries with China.

Key Words: China, United States, Latin America, Climate Change, Foreign Policy.

Keywords plus: Climate change, foreign policy, China-economic aspects, China, United States, Latin America.

SICI: 0122-4409(201301)18:1<321:CWCRLA>2.0.TX;2-E

Introduction: The Chinese Economic Factor

At present, the role of China in Latin America has been regarded as a pendulum between two widespread perceptions: as a threat, or as an opportunity. Given this situation, researchers have come up with a diverse set of empirical studies and policy debates in order to identify the role played by China in the region during the last decade.

Scholars have mainly focused on the impact of Chinese commercial presence in Latin American markets, ranging from complementary trade relations, such as the export of raw material for countries like Brazil, Chile, Argentina and Peru and the more recent export of energy commodities from Venezuela and Colombia, to trade and production disadvantages as a consequence of the shift in manufacturing markets dominated by Chinese products, as experienced in some Central American countries and Mexico (Jenkins and Dussel, 2009; León-Manríque, 2005; Cepal, 2008).

In a similar fashion, and due to China's growing international leadership role, a new area for research has emerged shedding light on global trends and practices that not only concern the "center states" of the international system. The "rise of the periphery" includes several Latin American countries, with some of them, Brazil in particular, already being or bound to be major actors at the international level. In addition, a renewed effort at regional integration is made in Latin America, including, inter alia, working jointly towards the construction of "economic safety nets" by way of interstate letters of understanding on the reduction of commercial barriers and joined free trade agreement negotiations (Kellogg, 2007; Bulmer-Thomas, 2001).

Beyond Economics: Why Bother?

There seems to be a widespread consensus in the extant literature that an economic perspective is all that is needed to understand current China-Latin American relations. The relevant debate largely takes place in terms of the positive or negative effects of the trade and investment dimensions of the relationship. Many observers seem to adopt a perspective in which the political impact of China's presence in Latin America is only regarded as a collateral effect or as a by-product of economic interests. However, such a perspective neglects or at least downplays a large number of "gray areas" of the Asian giant's presence in Latin America.

With some expectations, e.g., concerning the Taiwan issue and military ties between China and individual Latin American countries (Ellis, 2009; Dosch and Goodman, 2012), the political aspects of the relationship between China and Latin America have received short shrift. With this research I seek to complement the dominating economic lenses with a genuine political dimension, thus at least partially overcoming a notable gap in the literature.

I want to situate the discussion of contemporary Chinese-Latin American relations in the overall geopolitical context of the global leadership contest between China and the United States in the 21st century. In this debate, some scholars predict a (military) stand-off between the two countries for global hegemony as a result of China's rise to global superpower status and the ostensibly resulting revisionist stance vis-ä-vis the international order created and maintained by the current hegemon in all possible areas and arenas (Mearsheimer, 2001).

As such, China's increased presence in Latin America would just be another theatre for the aspiring hegemon's ambition to remake the world according to its own image and geopolitical interests (Halper, 2010). Or, as Joseph Nye's emphasis on "soft or smart power" would have it (Nye, 2004, 2011), China advertises its achievements in terms of economic growth and poverty reduction as a blueprint for other developing countries to follow the same approach. This strategy has reached a point where China has publically offered assistance and guidance to developing countries looking to emulate its economic model (Kurlantzick, 2007, p. 7).

At the same time, Latin America has strived to assert its political and economic autonomy vis-ä-vis the United States through (i) the creation of regional institutions aimed to develop an integrated regional space to strengthen the political, economic and social unity of Latin America and the Caribbean, e.g., the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) in 2004 and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) in 2008; and (ii) an increasing number of bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) designed as trade diversification and tariff elimination strategies.

In particular, countries such as Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico and Ecuador have signed FTAs with the European Union, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and phased tariff reduction was negotiated in the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement and the Andean Community.

This search for autonomy from the United States on part of (many, though not all) Latin American countries provides room for speculation and an interesting opening for political research as to whether China, as the main US competitor at the international level, might become the "new best friend" of the region in order to distance itself from its traditional status as the United States' backyard.

Following this line of reasoning, it is worthwhile to consider the increasing Sino-Latin American economic exchange with the recent downturn experienced by the U.S. hegemonic relationship to Latin America. As the political and economic ties between the region and its traditional hegemon weaken and the global leadership contest between China and the U.S. gains more ground, where do Latin American countries locate their interests vis-ä-vis issues of global and regional governance?

Global governance is understood as the sum of regulations or rules, set to organize global human societies, emphasizing the role played by formal political institutions in coordinating and controlling interdependent social relationships, as well as their ability to enforce the agreements in an environment that lacks a global political authority, such as the international system (Rosenau, 1999). Along these lines, the critical issue refers to cooperative arrangements for problem-solving (Riazati, 2006), or frameworks that imply a global scope and effect, with no visible authority and thus requiring a set of regulations and institutions that meet the proposed goal. Examples of such issues are nuclear proliferation, regulation of international financial markets, illegal drug trade, or human rights protection.

In this scope, this research aims to transcend the purely region-to-region or state-to-state level of analysis by focusing on the question whether a closer economic relationship between China and Latin America affects the latter's perspective on global and regional governance issues. In other words, given the wiggle room granted by the relative retreat of the U.S. from the region and the strife for autonomy (Lowenthal, 2010), is there an opening for China to use its increasing economic ties with Latin America to sway the countries' stance on global and regional governance issues towards its own position, i.e., away from the United States?

I do not pretend to establish a causal relationship by which deeper commercial and investment exchanges in and of themselves are responsible for (changing) foreign policy positions in Latin America. Rather I examine how these closer relations make discursive and subsequent policy shifts on specific issues of global governance possible, thus following a constitutive logic of explanation (Wendt, 1998).

I wish to embark on this larger endeavor by a heuristic study analyzing the positions of two Latin American countries (Brazil and Chile) - both heavily engaged in trade and investment relations with China - vis-ä-vis global climate change during the last decade. This paper employed discourse analysis in order to trace their positions along the two poles represented by the United States and China, respectively. The research design intends to answer the question whether there has been a noticeable shift in the two countries' position on global climate policy and if so, whether this change coincides with a discursive movement away from the U.S. and towards the Chinese approach.

Despite the impression that the selection of the cases is random, it is important to understand that both countries were chosen based on two major characteristics: their long-standing diplomatic relations and their profound trade and investment exchanges with both China and the United States.

Methodology: How to Measure Climate Change Discourse?

I race the positions of Brazil and Chile regarding global climate change policy with the help of discourse analysis. However, to do so we must tackle two major challenges: (i) different types of written and spoken material and their large size; and (ii) defining what type of material to use and how to process it in order to reach meaningful results in terms of the evolution of national climate change discourse over time.

In order to meet the first challenge in an efficient and productive way, the material selected for processing included the compilation of close to 2,500 documents, including both national and international press articles, official documents such as governmental conference publications, publications from international institutions, national official documents, laws, formal agreements, white papers, and a few academic papers1.

The second challenge was met by selecting a discourse analysis approach that was congenial for the reconstruction of the countries' positions on the crisis issue, climate change, by identifying policy tendencies, political actions and formulations that later overlap with economic exchanges, leading to a comprehensive result.

Due to the digital quality and the amount of the selected documents, the use of technologies such as Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QACDAS) is warranted. Unfortunately, these technologies still live in the shadows in terms of research in Political Science in general within Latin America, and in International Relations in particular.

However, they provide the possibility to conduct research in an orderly, rapid, interconnected, and "ecofriendly" fashion. The software Atlas.ti was thus chosen as a prime tool for the systematization of the available information as well as for the quantification of the results2.

The process of systematization created a database that was easily quantifiable through the use of six analytical categories - also called determining parameters - that provided insights into relevant milestones in the policymaking process, such as new government policies and interests, and identified some events that shaped the development and relevance of the climate change perceptions and discourses in the international arena during the selected period.

Yet, it is undeniable that some natural disasters with nationwide and international effects, like Hurricane Katrina in the United States and the continued droughts and heavy rain falls in Latin America, have shaped the perceptions of the climate phenomenon, awarding government summits and conferences a sense of urgency regarding the establishment of efficient procedures or frameworks of action.

These six categories were also analyzed on two levels of relevance: (i) as an idea (treated as a central topic of the text); and (ii) as an afterthought (referred to as tangential or partially supporting topic in the text), thus allowing for a wider observation of the development and correlation of the discourse.

Two stages were undertaken for the construction of the categories: (i) the raw analysis refers to the basic construction of the categories based on their preeminence throughout the texts as repeated ideas or afterthoughts; and (ii) the indepth results refer to categories linked to or centered on the discussion of the main subject, related to context changes or relevant events3. Let us now consider the six categories in detail.

Climate Change

As evident and relevant as the term seems, it was selected in its pure discourse form-induced definition, including the use or recognition of the term within or outside state action or policy initiatives, thus providing the possibility for a quantifiable use, acceptance or importance of the term in political discourses of state representatives.

Binding Framework

A substantial and critical topic when addressing the climate change issue. The term includes early mentions of legal or political frameworks of interaction between the selected countries, as well as the signing, and enforcing of the Kyoto Protocol at the national and international level. In later years, includes new policy initiatives seeking to establish regulatory frameworks; i.e. new protocols, draft global agreements and legal frameworks.

Gas Emissions

In early texts, carbon dioxide emissions were considered the main climate deterioration cause. Later on, it was included in the larger concept of climate change as the first tangible and measurable representation. The consistent relevance of the concept makes it fundamental for the comprehension of the discursive evolution comprising all sorts of measures to ease climate change effects. The term also includes related concepts such as greenhouse effect, global warming and pollution, inside or outside policy initiatives, or official statements on the subject.

Cooperation, Finance and Technology Transfer

Since 2003, new challenges have risen concerning the international character, the institutional foundations and cooperation targets and dynamics, not only between Brazil, Chile, China, and the United States but also concerning third-party participation and understandings. The concept also takes account of some provisions or proposals for project-financing initiatives - a sensitive point - as well as the transfer of technology as a policy initiative or as a fundamental part of cooperative framework agreements supporting the actions of other less developed parties.

Role of States (developed and developing)

A crucial issue in global climate change policy refers to defining or imposing a role to states according to their economic development level. The four countries posed views regarding duties, responsibilities, and participation of actors according to their classification as developed or developing economies. The category rates the official political position of the countries on the subject.

Shared Responsibility

This category was built upon the findings produced during the second half of the last decade where the concept's use is a highly defining part of current management of reform initiatives the construction of future regulatory frameworks. It also links directly with the characterization of the roles of the states, mentioned in category #5.

Main Findings: Tracing the Climate Change Discourse between 2000 and 2009

After having briefly described the methodological context of the project, let us now turn to the analysis in detail, i.e., bringing together the international context (China as a global player and its increased interest in Latin America), the subject (global climate change policy), the object (Brazil and Chile as sample Latin American countries), and finally the six categories of discourse analysis.

Which position do you play?

As mentioned earlier, the opposing poles, China and the United States, provide the backdrop for the analysis. Brazil and Chile, in turn, are considered as countries that struggle to find a place between the two poles, including some wiggle room for proposing their own approach in the area of global climate change.

I study the dynamics of the discursive evolution along three distinct dimensions: (i) a starting position - based on the climate change-related discourse pursued before 2003 -; (ii) a final position - based on the current discourse pursued since 2009 -; and (iii) an in-between position - based on the discourses' shifts or modifications derived from the countries' interests or contextual junctures between 2003 and 20094.

Starting the Weather Change

China5

Before the 1990s, China pursued an inward-looking, ideology-driven strategy that relegated many global issues, including climate-related topics, strictly to the national interest sphere, leaving them off-limits for the international arena and inducing a relatively scarce participation of the country in international forums. This course of action only changed after the Tiananmen massacre in 1989, when the rejection of the international community forced China to formulate an open and participative strategy that included the governmental promotion of trade and investment as well as an increasingly active participation in international organizations and global debates (Goldstein, 2001).

Ever since the 1980s, China has recognized the existence of climate and global environmental phenomena as well as the need to act upon it. The resulting discourse had two different approaches, first as a scientific development-based issue managed by the Chinese Meteorological Administration Office (MAO) (Institute for Global Dialogue, 2011) following the guidelines of the Agenda 216 and later, in the second half of the 1990s, as a policy-building issue handled by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in close relation to the formulation of the energy policy (Institute for Global Dialogue, 2011, p. 18).

At the beginning of the 2000s, initiatives to join international efforts provided the foundation for the first cooperative agreements regarding the development of alternative energies, signed with Australia and some other developed countries, as well as a political commitment by ratifying the Kyoto Protocol in 2002.

As a result, China's discourse focused on the lacking response from industrialized countries regarding targeting the agreed commitments on reducing carbon dioxide emissions, pollution control practices and the development of mitigation strategies for other derivate effects of climate change, such as increasingly repeating droughts.

United States7

In contrast to the Chinese position, the United States posed an open, active leadership, both nationally and internationally, promoting and engaging in actions that moderate the climate change effects. The Reagan and Clinton administrations were rather proactive regarding cooperation and supporting projects on environmental managing, thus contributing not only to develop mitigation strategies and research efforts, but also by providing financial support to countries' initiatives, most of them from Latin America.

At the beginning of the 2000s decade, the trend was radically altered when the Bush Jr. administration declared its refusal to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, placing the climate issue aside on behalf of a political agenda that emphasized employment, the national interest, and later, after the 9-11 events, focusing on homeland security. As a result of the latter, the official discourse on climate change was relegated from its active standpoint towards the background, generating a symbiotic relationship and almost synonymy between carbon dioxide emissions reduction and climate change.

By 2002, a three-component policy was issued addressing (i) an 18 % cut on gas emission by 2012; (ii) investment in science and technology development; and (iii) the promotion of international cooperation (U.S. Department of State, 2005).

Brazil8

From the early 1970s, Brazil provided an example for an internationally active country on the climate issue front, searching for proper means and strategies to safeguard the Amazon Forest from illegal exploitation (such as forest cutting and burning), but also preparing and preventing the Brazilian population and economy from natural weather phenomena (such as La Niña).

During the three following decades, the country's main concern was directed at obtaining financial aid and political support from international sources, for instance cooperating with relevant countries, like the United States, and backing the establishment of international institutions that had the potential to become influential players in environmental policy formulation as the Kyoto Protocol.

The initiatives were always closely pursued in line with the main national objectives: poverty reduction and economic development. During the first years of the 2000s, Lula's administration pursued an even greater effort to include the environmental and climate change issues into the national agenda, building a "more stringent system of law enforcement" (Institute for Global Dialogue, 2011, p. 31) that aimed to restrain the illegal environmental economies, and thus creating new opportunities in alternative energy development and green-based goods production.

Chile9

Before the 2000s, Chile managed a low political profile on environmental and climate change issues, participating in international conferences but focusing only on the weather effects on national disaster scenarios, or on the environmental implications of the industrialized production model.

In 2001, due to a significant ice cap detachment and melting in the northern region of the country, the scientific concern regarding climate change rapidly grew, making the issue a pressure group topic, not only for green activists and environmentalist groups but also for political and industrial conglomerates that saw an imminent effect on the country's national and economic stability (Comité Nacional Asesor sobre Cambio Global-Gobierno de Chile, 2006).

The Final Weather Change

China10

By the end of the 2000s, China sets an example as a global actor with a successfully booming economy and as an international voice of developing countries' interests to achieve and maintain economic growth with sustainability. This strategy includes a deep concern for the environment, a widespread use of alternative renewable energy sources, and a concern for the side effects of mass production such as global warming, increasing gas emissions, spreading pollution, temperature and sea level rising, extreme weather, natural resource shortage, and recurring natural disasters, etc.

Along these lines, China has emphasized three key elements in its political discourse on climate change, occasionally in contradiction to its real actions on the ground: (i) the defense of the common, yet differentiated responsibilities and duties principle; (ii) an approach identifying reasonable and sufficient target goals to achieve long-term climate change moderation; and (iii) the allocation for proper financing resources to address environmental issues.

The first element has been included in China's defense of developing countries' responsibility on climate change, highlighting the constraints that poor or less industrialized nations face when undertaking efforts to reduce climate change. China often manages to pose as a champion for developing countries, although on occasions such as during the Copenhagen Summit 2009 it leaves a disturbing perception of antagonistic actions against the United States11.

The second element describes China's desire for a more comprehensive and binding framework of action, including reasonable timeframes and clear and detailed commitments to address the different climate change causes and effects, agreeing not only to a global goal but to individual commitments of the signature countries. China itself has proposed to cut gas emissions and pollution up to a 50% by 2020. However, at the Copenhagen Summit, China was strongly inclined towards leniency for developing countries, showing zero tolerance for acknowledging developed countries' limitations.

Although the last element has been expressed by Chinese representatives at several opportunities, and is considered a pivotal stone supporting the binding framework's commitments, no definitive proposition has been presented by China, apart from sporadic references on establishing a "Green Fund", or the adoption of an international environmental tax devoted to finance efforts against negative climate change outcomes.

Today, China's economic success and increasing political influence create difficulties for maintaining a coherent discourse regarding whether to present itself as a developing country of large proportions, or rather to restate its official position acknowledging the recently acquired status as a developed country12.

United States13

After 2009 the country's position has gradually introduced the phenomenon of climate change on the list of international political lobbying topics, acknowledging specific impacts to the environment - such as carbon dioxide emissions, temperature rising, and sea current shifts - thus supporting a less determinant position in the introduction of climate change as a relevant issue on the international agenda.

However, the United States' actions remain scarce and far from committing to any future binding framework, leading to a doubtful, irrelevant or ineffective discourse, reinforced by the retreat of Canada from the Kyoto Protocol after last year's progress evaluation and consecutive failure. According to the United States' government, there is still a lot to be done from an individual country perspective, especially concerning the responsibility of developing countries, before being able to agree on an internationally binding framework that will be effective and results-oriented. It remains clear that the United States, although a relevant actor on the international scene, stays on the sidelines of the global climate change debate with a modest attitude. Instead, it aims at a fast response in bilateral understandings, treaties or cooperation agreements, focusing on addressing the phenomenon as a collateral damage of economic exchanges.

Such a scheme has been kept since the first half of the last decade and relates to the national discourse pursued by the respective administrations in which the means to address the effects of "climate instability" should come from the market and the national economic dynamics, as well as by a large field of scientific research projects14.

Brazil15

By 2009, Brazil has continued playing a relevant role in the international climate change debate, raising international awareness, promoting the consensus strategy in order to overcome the climate effects and working on its national objectives of sustainable growth and deforestation control by utilizing multilateral means, a legacy of the Lula administration.

Brazil's multilateral efforts to raise awareness of the climate change phenomena has included a cooperative exchange of its extensive work on national environmental problem-solving and sustainable development, translating in a series of agreements with both the governmental and the private sector, while continuously supporting the formulation of what was thought to be an extended Kyoto Protocol built upon a series of new commitments presented at international forums.

More recently, as a result of the failed attempts to extend the Kyoto Protocol and the successful practices as part of the BRICS group, Brazil co-founded the BASIC group, a states' association focused on accomplishing an unanimous acknowledgment of the "principle of shared but differentiated responsibilities", aimed to lead the formulation of an effective binding framework.

Likewise, Brazil stated its concern regarding the origin of financing resources before addressing any further commitment in the climate change arena. As a result, a request for a previous agreement on the creation of a "Green Fund" or the corresponding provisions on the origin and administration of any financial resources dedicated to climate change efforts and future obligations were issued.

However, under the Rousseff administration, the focus on reigniting the economy, overcoming infrastructure bottlenecks and cutting back governmental expenditure might eclipse the relevance of climate change in Brazil's foreign policy during the coming years.

Chile16

The country's current position demonstrates a moderate participation in the global climate change discourse, usually as part of a regional approach characterized by two trends: (i) the support for a binding working framework, and (ii) the bilateral approach to cooperation.

The first trend, as established by the Latin American joint statements presented at the Copenhagen Conference in 2009, the Cancun Summit of 2010 and the Durban Conference of 2011, is based on an unanimous acknowledgment of the climate change issue, its scope and the relevance of its effects for present and future policy formulations, states' decision-making and governmental action, while implementing a shared responsibilities principle, related to states' resources and capabilities (COP 17- G77 and China, 2011).

The second trend, a bilateral approach, seeks alternative methods to address the climate change issue with a diversified methodology and a dynamic political interaction. As a result, a bilateral cooperative framework for climate change was promoted, including green clauses in trade agreements and general issue-centered cooperative agreements (from research projects to supporting partnerships with neighboring states and expert countries outside the region, and technology exchange on climate change-related issues, i.e., pollution, gas emissions, polar-cap protection and green production procedures).

In-Between the Weather Changes

China17

According to the National Strategy of Sustainable Growth, the Chinese focus after 2003 was placed on reaching cooperation agreements on alternative energy projects with neighboring countries, hoping to facilitate the enlargement of the industrial base as well as to mitigate the negative side effects of mass production, e.g., pollution and the excessive consumption of natural resources (National Development and Reform Comission of the People's Republic of China, 2007).

During the next three years, China's experience of rapid industrial development and collateral environmental damages created the proper scenario for the "developing countries' limited capacities" discourse, emphasizing the political and economic impact experienced by underdeveloped countries while international pressure urged a successful implementation of economic reforms and growth-incentive policies. This discourse was subsequently adopted by other developing countries leading to what will be known as the "shared responsibility principle".

At the national level, the concern over the increasing repercussions of climate change drove the State Council to draw up the First National Assessment Report on Climate Change (NARCC) in 2006. This document included projections that redflagged the progressive increase of gas emission, pollution, and other weather and resource implications in the time to come. As an immediate reaction, research institutes and think-tanks were mandatorily established as national government advisors and information centers in the process of formulating a National Climate Strategy.

In 2007, China's first National Climate Change Program was presented, announcing the establishment of an official institutional branch, the high-level 'National Climate Change Coordinating Leading Small Group', in change of monitoring and coordinating national climate change policy and projects. In the international arena, the Program established the position of an official spokesman, a Special Representative for climate change negotiations, in order to address the issue in multilateral forums.

The Program gathered the traditional Chinese approach on climate change-related topics, i.e., the control procedures for carbon dioxide emissions, alternative energy project support, incentives for cooperation agreement, especially regarding other developing countries, and the exchange of technology, resources and know-how with both developing and developed countries.

In addition, the Program stipulated China's commitment to lead climate change initiatives in order to formulate an internationally binding framework, relying on the "shared but differentiated responsibility principle", and capable of effectively addressing the issue at the multilateral level.

United States18

Only after the second half of 2005, policy formulations considered issues beyond national security on their own ground, decoupling topics from the security doctrine discourse and addressing them as relevant factors for national political, economic and social stability.

During that period, the climate change issue became relevant to the private sector and the scientific community, receiving financial and some mild political support to develop green procedures, more efficient technologies, and new areas of climate research, aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions and other types of pollution, while maintaining the model and velocity of economic mass production.

Despite the lack of an official discourse that reinforced these initiatives beyond a market-centered issue, many industrialized countries provided support for the academic and private sector through international research teams and technological transfer programs.

The climate change issue was reintroduced in the US in August 2005 by the same wind that brought Hurricane Katrina to New Orleans, and both the public and the political spectators emphasized the relevance of this overlooked topic. This newly found interest reinforced the idea that extreme weather conditions are a result of negative effects from misguided developing programs.

The concept laid out the three foundations of the emerging U.S. position: (i) the definition of climate change as an economic effect that can be managed with the proper procedures, adequate planning, and infrastructure; (ii) the acknowledgment of developing countries' responsibility as contributors to climate change; and (iii) the lacking weight of any international framework, such as the Kyoto Protocol, to adequately address the issue of climate change (Congressional Research Center, 2011).

Brazil19

Since 2003, the country has been a proactive regional and international environmental actor, eager to contribute to a global understanding of the climate phenomenon by way of exploring and developing alternative energy projects, and monitoring changes and projecting future scenarios. In addition, the global concern took Brazil's policies to a higher level requiring constant interactions with international organizations and an increasingly active participation in multilateral forums, where most of the country's policies and standpoints on the climate debate became a regional point of reference.

Another characteristic of the Brazilian climate change approach identifies domestic actors, such as large companies, as key governmental partners when planning, formulating or negotiating international frameworks. As a result, a participative policy formulation mechanism for climate change was created in 2004, where private lobby groups were given a role in the policymaking process as well as for the implementation of national programs.

In 2008, two national plans - the Sustainable Amazon Plan and the National Plan on Climate Change (PNCC) - were launched leading to several know-how cooperation agreements with regional neighbors, such as Venezuela and Ecuador, and other nations such as Australia and Canada. In addition, the PNCC established ambitious goals in order to change the fuel and carbon-based economy towards an alternative energy-based one within twenty years20.

At the dawn of the last decade, Brazil's position supported an extension of the Kyoto Protocol as a base agreement for a future binding framework to address climate change in light of the shared but differentiated responsibility principle. However, the political transition between the Lula and Rousseff administrations posed new challenges to the climate change issue, removing it from its central position in Brazil's international agenda.

Chile21

During 2003 and 2006, Chile's discourse and actions on climate change remained restricted to the national realm in an attempt to mitigate the environmental impact of the economic boom and the newly signed free trade agreements with the European Union and some Asian countries. In addition, the government emphasized the regional level as the base for effective measures to counteract the negative effects of climate change, while sustaining a continued economic growth. During those years, the United States became a major cooperation partner, exchanging know-how, technology and conducting joint research studies on carbon dioxide emissions and alternative renewable energies (Conama, 2008).

As a result of the rising concern promoted by devastating floods and long-lasting droughts affecting the economy's strongholds of agriculture and fishery, the Environmental National Commission (CNMA) requested a national study in order to project Chilean climate development in the 21th century. The resulting study highlighted the need to politically address the issue before losing the grip on the emerging causes (carbon emissions, extreme resource consumption, and pollution). As a result, the government debated and subsequently formulated comprehensive policies, leading to the National Strategy on Climate Change in 2006.

In turn, in 2008 a four-year action plan, the Climate Change National Action Plan, suggested a discourse and a strategy in order to address climate change at the national and international level. Four main points stand out in this Plan: (i) signing the Kyoto Protocol, despite not being required to take any specific action; (ii) the acknowledgment of the country's limited understanding and ignorance regarding the economic costs and effects of climate change; (iii) the need for an alternative, sustainable economic model; and (iv) the use of multilateral means to address a global issue with national repercussions as a problem affecting all countries in different proportions (Conama, 2008).

Conclusion: Changing Weather in Latin America

It is clear that climate change shifted from a backstage topic to a major issue of global governance during the last decade, becoming a hotly debated topic in international forums, often putting developed and developing countries at loggerheads. In the current scenario of growing disagreements between industrialized and poor countries, this paper identified the United States' and China's discursive approaches as examples of opposing positions within the international discourse on climate change.

I have embedded the global U.S.-China rivalry within the contemporary reorientation of Latin American foreign policy in general, and towards issues of global and regional governance in particular. However, I am fully aware of the fact that other factors also have a bearing on the position of Brazil and Chile regarding global climate change policy, e.g., the impact of other Latin American countries on Brazil's and Chile's perceptions of the climate change issue, the possibilities to enter into other markets in a competitive way abiding to their political requirements, and international political, economic and environmental trends, etc.

During the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil, Chile, and China officially acknowledged climate change as a policy guideline in the economic development process as well as for future national projections. On the other hand, the United States considered climate change as a side-effect of the market economy in its failed attempt to achieve sustainability.

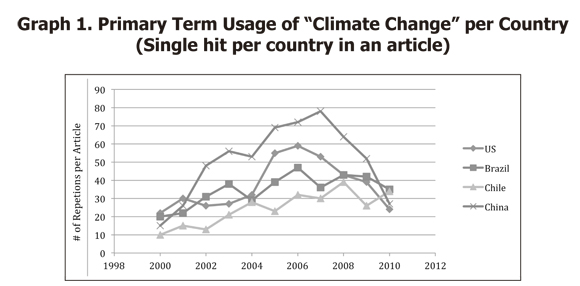

The following graphic show the countries' mentioning of the term "Climate Change", demonstrating (i) China's increasing use; (ii) Chile's moderate usage; and (iii) Brazil frequent use of the term, compared to the fluctuating but generally decreasing use by the United States.

In addition, it is possible to identify a parallel increase between China's trade exchanges with Chile and Brazil, and their increased mentioning of the climate change issue, as well as shared policy formulations - framed within international cooperation agreements with Chile and within BRICS's joint statements in the case of Brazil. In a similar fashion, the trade exchange and usage of the term between the Latin American countries and the United States seems to fluctuate in the opposite direction.

Nevertheless, Latin American countries' motivations are based on different approaches, as Brazil's interests relate to multilateral strengthening and Basin protection and Chile's interests to a sustainable agriculture and fishery production, suggesting a possible independent trend moving away from either United States or China's discourses.

Even so, during the relevant time period, Brazil, Chile, and China supported the Kyoto Protocol, thus showing their willingness to commit to a binding framework regarding an important issue of global governance. In comparison, the United States has refrained from doing so, highlighting a skeptical attitude regarding the effectiveness of a global protocol on what it regards a national market issue by committing to a target goal on gas emissions.

In similar fashion, there has been a common interest between the four countries in terms of addressing carbon dioxide emissions since early on, but the discursive tendency of Brazil, Chile, and China gradually diminished its prominent role in global climate change, giving way to other concerns such as alternative energy development and sustainable technology improvement. In contrast, the United States continues portraying carbon emissions as the main governmental concern regarding climate change, thus relegating other aspects, such as the previously mentioned ones, to private and academic endeavors.

In terms of discursive changes, the inclusion of the multilateral level generated the most noticeable alignment of the two Latin American countries with China, highlighting cooperation and technology exchanges and linking discourses and actions in united fronts.

Not only the discursive approach regarding climate change evolved under the "developing vs. developed countries" flag placing Brazil, Chile, and China in one corner, and the United States in another, but the evolution of trade and political exchanges throughout the last decade moved Latin America and China closer together in both bilateral and multilateral arenas.

In terms of climate change's financing methods and further binding framework developments, the four countries stand on the same page addressing the need to specify (i) the source and origin of the resources, and (ii) general institutional guidelines, yet without real commitments to a specific proposal.

Finally, throughout the last decade and until today, defining the role and responsibility of states marked a clear discursive divergence between the United States on the one hand, and Brazil, Chile and China on the other.

This aspect relates directly to the economic sphere regarding the long-lasting liability dispute between industrialized and developing countries over the environmental effects of the economic development process. In this debate, China and the Latin American countries are on the same side, emphasizing their limited ability to commit to any particular obligation, while the United States ostensibly possesses more than enough resources to address the issue on its own.

For the United States' government, the primary cause of the climate change problem comes as the direct result of misguided development processes in poor countries. It therefore emphasizes the need for those countries to openly acknowledge their responsibility and act on the matter.

The disagreement reached a common ground during the middle of the decade when both sides acknowledged their proper responsibility, although the quarrel moved on in terms of the extent of the responsibility and regarding the corresponding duties of either side.

Without a doubt, there still a long way to go from establishing a causal chain between trade exchange and discursive alignment between China and Latin America, though my analysis brings us a step closer by posing a constitutive relationship between both factors regarding the issue of climate change. However, it seems plausible that the increasing economic proximity between China and Latin America underwrites the tendency of detaching the latter from the United States on issues of regional and global governance. As a result, I encourage more research on the global-political ramifications of the rapidly evolving economic Sino-Latin American relationship, where countries such as Colombia are challenged to find a position in the tug-of-war between China and the United States.

Footer

1The database Lexis-Nexis has been used as the main source for the press articles. The parameters used consisted of a timeline of ten years - 2000 to 2010 -, the four countries - Brazil, China, Chile and the United States - and a keyword - Climate Change. For the remaining publications the sources varied from official institutional or organizational sites, national government webpages, and other official and academic documents in digital format, databases, or websites.

2Atlas.ti is a U.S. designed software that allows the handling of text, photos, videos and audio digital files for qualitative analysis, helping extraction, categorization and data-segment interweaving of a large variety and number of sources. When processing the files, a so-called hermeneutic unit is created to gather and link information. From the Atlas.ti official website, In: http://www.atlasti.com/product.html.

3An example is represented by the establishment of the Kyoto Protocol leading to the global concern about carbon emission rates.

4Each of the three dimensions is the extrapolated result of the hermeneutic units (HU), created with the software Atlas. ti. There were four HU consisting of nearly 3,000 press articles and official documents.

5The discursive evolution of China's initial position is the result of the analysis of 95 press articles included in China's HU file for Atlas.ti.

6As suggested by the Rio Declaration, the Chinese version of the Agenda 21 was drafted and officially presented in 1992. The document, "China's Agenda 21: White Paper on China's Pollution, Environmental, and Development in the 21th Century", established an action plan to transform the current development model towards a sustainable and efficient new model.

7The discursive evolution of the United States' initial position is the result of the analysis of 110 press articles included in U.S.' HU file for Atlas.ti.

8The discursive evolution of Brazil's initial position is the result of the analysis of 131 press articles included in Brazil's HU file for Atlas.ti.

9The discursive evolution of Chile's initial position is the result of the analysis of 65 press articles included in Chile's HU file for Atlas.ti.

10China's discursive evolution since 2009 is the result of the analysis of 180 press articles included in China's HU file for Atlas.ti.

11There has been much speculation on the role played by China in the failure of the Copenhagen Summit. Although the majority of the blame fell on the Obama administration, the Chinese negative attitude towards acknowledging the limited capabilities of the developed countries appear to some as an effort to block negotiations and to pose a direct opposition to the United States' proposal and thus to its relevance in the climate change debate (Christoff, 2010; various press releases from The Guardian and CBS).

12China's industrialized development and increasing pollution contributions were first outlined in the Annual Report on Actions to Address Climate Change in 2010, indicating the need to increase China's responsibility and commitments concerning global climate change.

13The United States' discursive evolution since 2009 is the result of the analysis of 166 press articles included in US's HU file for Atlas.ti.

14Despite having an official spokesperson and a significant number of national organizations addressing the climate issue at the international level, the official position remains uncertain, almost left out of the political agenda or identified as a private issue, serving even as a discursive platform for radical environmental groups.

15Brazil's discursive evolution since 2009 is the result of the analysis of 183 press articles included in Brazil's HU file for Atlas.ti.

16Chile's discursive evolution since 2009 is the result of the analysis of 92 press articles included in Chile's HU file for Atlas.ti.

17China's discursive evolution during the period 2003-2009 is the result of the analysis of 388 press articles included in China's HU file for Atlas.ti.

18The United States' discursive evolution during the period 2003-2009 is the result of the analysis of 378 press articles included in US' HU file for Atlas.ti.

19Brazil's discursive evolution during the period 2003-2009 is the result of the analysis of 355 press articles included in Brazil's HU file for Atlas.ti.

20In December 2008, President Lula launched the National Plan on Climate Change, aimed at eradicating illegal deforestation in the Amazon region, including the commitment to decarburize the Brazilian economy by 2020.

21Chile's discursive evolution during the period 2003-2009 is the result of the analysis of 546 press articles included in Chile's HU file for Atlas.ti.

Works cited

Bulmer-Thomas, V. (2001). "Regional Integration in Latin America and the Caribbean". In Bulletin of Latin American Research 20 (3): 360-369. [ Links ]

CEPAL (2008). Economic and Trade Relations between Latin America and Asia-Pacific. The Link with China. Available from http://www.eclac.org/cgi-bin/getProd.asp?xml=/publicaciones/xml/5/34235/P34235.xml&xsl=/comercio/tpl/p9f.xsl&base=/comercio/tpl/top-bottom.xsl. Downloaded: 24/08/2012. [ Links ]

Christoff, P. (2010). "Cold Climate in Copenhagen: China and the United States at COP15". In Environmental Politics 19: 637-656. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional del Medio Ambiente Conama. (2008). Plan de Acción Nacional de Cambio Climático. Santiago de Chile: Conama. [ Links ]

Comité Nacional Asesor sobre Cambio Global. Gobierno de Chile (2006). Estrategia Nacional de Cambio Climático. Santiago de Chile: Gobierno de Chile. [ Links ]

Congressional Research Center (2011). U.S. Global Climate Change Policy: Evolving Views on Cost, Competitiveness, and Comprehensiveness. Available from: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL30024.pdf. Downloaded: 24/08/2012. [ Links ]

Dosch, J. and D. Goodman (2012). "China and Latin America: Complementarity, Competition, and Globalisation". In Journal Of Current Chinese Affairs 41 (1): 3-19. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. E. (2009). China in Latin America: The Whats and Wherefores. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. E. (2012). "The Expanding Chinese Footprint in Latin America: New Challenges for China and Dilemmas for the US". In Asian.Versions 49: 1-34. [ Links ]

Goldstein, A. (2001). "The Diplomatic Face of China's Grand Strategy: A Rising Power's Emerging Choice". In The China Quarterly 168: 835-864. [ Links ]

Halper, S. (2010). The Beijing Consensus. How China's Authoritarian Model Will Dominate the Twenty-First Century. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Institute for Global Dialogue (2011). The Global South and the International Politics of Climate Change: Proceedings Report of the International Workshop: Negotiating Africa and the Global Souths Interests on Climate Change. Available from http://www.igd.org.za/publications/igd-reports/finish/8/215. Downloaded: 27/07/2012. [ Links ]

Jenkins, R. y E. Dussel (2009). China and Latin America: Economic relations in the twenty-first century. Mexico City: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). [ Links ]

Kellogg, P. (2007). "Regional Integration in Latin America: Dawn of an Alternative to Neoliberalism?". In New Political Science 29 (2): 187-209. [ Links ]

Kurlantzick, J. (2007). Charm Offensive: How China's Soft Power is Transforming the World. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

León-Manríque, J. L. (2005). "China-América Latina: una relación económica diferenciada". Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior 75: 28-47. [ Links ]

Lowenthal, A. F. (2010). Obama and the Americas. Foreign Affairs. Available from: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/66467/abraham-f-lowenthal/obama-and-the-americas. Downloaded: 22/08/2012. [ Links ]

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

Nye, J.S. (2004). Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Nye, J. S. (2011). The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Rosenau, J. (1999). "Toward an Ontology for Global Governance". In M. Hewson and J. S. Timothy (ed.). Approaches to Global Governance Theory. Alban:, State University of New York. [ Links ]

Riazati, S. (2006). "A Closer Look: Professor Seeks Stronger U.N.". The Daily Bruin. Available from: http://www.dailybruin.com/index.php/article/2006/10/a-closer-look-professor-seeks-. [ Links ]

U. S. Department of State (2005). U.S. Climate Change Overview. Available from: http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/seminar/application/pdf/sem_pre_usa.pdf. Downloaded: 24/08/2012. [ Links ]

Wendt, A. (1998). "On Constitution and Causation in International Relations". Review of International Studies 24 (5): 101-118. [ Links ]