Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Papel Politico

versión impresa ISSN 0122-4409

Pap.polit. vol.21 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2016

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.papo21-1.dlcr

The Dispute for Land in Colombia over the Resguardos: Concepts, Analytical Angles and Standpoints*

La disputa por la tierra en Colombia sobre los resguardos: conceptos, ángulos analíticos y puntos de vista

Germán Andrés Mora Vera**

*This article is a result of the doctoral course investigation that is currently under elaboration. I would like to use this space also for extending my deep gratitude and appreciation to Rina Kurachi, Master in Latin American Studies, whose professional comments and suggestions enriched this written. Finally, I also desire to demonstrate my appreciation to my professor Doctor Isamu Okada from Nagoya University.

**Graduated from the Pontifical Xaverian University in Bogotá, Colombia and holds a Bachelors' Degree in Political Science. He is a Master of Arts in International Development and is a current Ph.D student at Nagoya University in Japan. He has been working as a teaching and research assistant at the same university. For further contact: andreskurachi@gmail.com

Recibido: 6 de abril de 2015 Aprobado: 17 de noviembre de 2015 Disponible en línea: 30 de junio de 2016

Cómo citar este artículo:

Mora Vera, G. A. (2016). The dispute for the land in Colombia over the resguardos: concepts, analytical angles and standpoints. Papel Político, 21(1), 57-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.papo21-1.dlcr

Abstract

For over 400 years there has been a conflict between the governments and the indigenous peoples in Colombia over the lands of resguardos that still goes on today. Through a comparative study carried out within what is denominated as the Upper and Lower angles, this article attempts to show the differences and similarities between the interests and beliefs of these two parties over these lands. The academic discussions involved in this study reveal also that there is not only a lack of consensus between the authors that study this topic, but also demonstrate that there is a gap between the principles enacted in the rule of law and the reality, which keeps prolonging this conflict.

Keywords : Colombia; indigenous, government, land dispute, resguardos

Resumen

Por más de cuatrocientos años ha existido un conflicto entre los Gobiernos y los indígenas en Colombia por las tierras de los resguardos y que aún hoy en día sigue vigente. Este artículo intentará demostrar, por medio de un estudio comparativo realizado dentro de lo que se denomina los ángulos superior e inferior, las diferencias y similitudes entre los intereses y las creencias que estos dos actores tienen sobre estas tierras. Las discusiones académicas que se mencionan en este estudio revelan que no solo hay una falta de consenso entre los autores que estudian este tema, sino que, a su vez, demuestran que hay una brecha entre los principios establecidos en la ley y el contexto real que sigue prolongando este conflicto.

Palabras claves: Colombia ; indígenas; Gobierno : disputa de tierras, resguardos

Introduction

Over four hundred years ago Colombia was colonized by the Spanish crown and since then, a struggle begun between the native ethnic groups and governmental regimes over land, lasting until the present date. This scuffle has become more complex throughout the years because the parties involved - the government and the indigenous groups -have different conceptions over the meaning of the land, especially after the Spanish crown created the so-called resguardos.

The resguardos, or indigenous reservation areas, as it could be translated to the English language, are special geographical zones designed by the Spanish crown during the colonization period for the safeguarding and protection of the rights of the indigenous communities, specifically from any possible dominance, usage, and invasion from third parties, including governments themselves. After its enactment, this political and legal measure gave the indigenous communities collective property rights to own and use these areas for living and developing their traditional activities, while at the same time preserving the cultural background of the territory. In other words, no one different to the indigenous peoples belonging to the community assigned to live in a specific resguardo, not even the government, was allowed to enter the resguardos without permission of their members. However, gradually the resguardos became the reason behind a conflict between the indigenous peoples and the governments that has been prolonged for over a century. This scuffle has been caused because, on the one hand, the indigenous peoples argued that they have continuously experienced intromissions into their resguardos by the government itself and also by third parties that have neither considered the politics, laws, or their rights to previous consultation to enter into these zones. On the other hand, the government claims that the policies, laws, and rights to previous consultation are by all means being respected, protected, and, at the same time, the resguardos are not under the intermission of unauthorized parties.

Hence, this article will explain the conflict between these groups through some relevant academic standpoints that have attempted to study this dispute. I divided this analysis in two formulated categories called the Upper and Lower angles in order to simplify these standpoints, considering that one of the factors which has made this scuffle more complex is the intricacy in the analyses performed and variety of opinions. The purpose of this article will be focused on demonstrating the existence of a gap between these perspectives - which did not coincide in the past and still do not coincide now - and the lack of a consensus to be used as the future starting point for a fixed position between the parties involved in order to reduce the intensity of the current existing conflict.

The Origins of the Land Dispute in Colombia

Taking a look back in the history of Colombia, we can find that most of the constant conflicts occurred in this country have land as a common factor; one of the most important and necessary basic resources for life and development, and one of the main reasons for the commencement of confrontations between groups which, in this case, are the indigenous peoples and the government.

After the Spanish crown invaded, occupied, and colonized this territory between the 15th and 19th century, specifically from 1490 to 1819, the indigenous peoples who were dominated, forced to work the land in favor of the Spaniards' interests, and almost extinguished while the colony lasted, gradually started to receive some special privileges given by the higher governors of the crown. Their intention was not only to avoid their extinction but also to maintain control of the remaining natives in concentrated and organized parcels through these political and legal measures in order to preserve their lives for future generations.

When the Spanish crown abolished slavery in 1542, along with the enactment of what is known as the New Laws (Nuevas Leyes in Spanish), the Spanish crown gave these indigenous peoples some freedom and privileges as long as they remained loyal to the crown without committing revolutionary acts (Newson, Linda. A; 2008, p. 178). The resguardos were perhaps the most evident and notable change in the relationship between colonizers and indigenous peoples, since with this reform the resguardos came to be understood as geographical areas owned by the indigenous peoples that they could use freely without the intervention of the government or third parties. In the words of Copland Aaron, "the resguardo is characterized by being a land assignation, according to the indigenous tradition of property, to a group of aborigines. The originality of the system was based on the fact that the sale of these respective areas was not permitted..." (Copland, Aaron; 1978, El resguardo). Both authors, Newson and Copland, consider in their studies the crucial role played by the crown after the promulgation of the New Laws in the attempt to modify the relationship between colonizers and indigenous peoples; however, unlike Newson, Copland affirms that resguardos were a "sui generis land ownership form, some kind of discrimination, which was prolonged a clear demographic policy that prevented the mingling of Spaniards, indigenous, half-caste, and African peoples" (Copland, Aaron; 1978, El resguardo).

The Ambiguous Concepts of Resguardos

The resguardo will be defined as a specific land area given by the crown, during the colony, and the government, in the times of the republic, to indigenous peoples, according to their beliefs. It aims to protect and preserve these native groups by collectively granting them a space where they can live, organize, and develop their own traditions, customs, and lifestyle without paying tributes or being subject to the intervention of the government or other parties. For a resguardo to exist, it must be comprised by a territory and an indigenous community, and they are catalogued by all means as inalienable, imprescriptible, and indefeasible1. These principles and concepts are also found in Law 21, 1991(Law 21/1991, March 4th) and Article 21 of Decree 2164, 1995, which define resguardos as

a collective property of the indigenous communities, which are constituted in favor and in accordance with Articles 63 and 329 of the Constitution, being inalienable, imprescriptible, and indefeasible. These areas are a legal and sociopolitical institution of special character, conformed by one or more indigenous communities, under the titles of collective property that also has guarantees of private property, possessing a territory and governed, for management and internal lifestyle purposes, by an autonomous organization supported by the special indigenous legislation and their own normative system (Decree 2164/ 1995, December 7th).

Even though resguardos have a single legal concept, the constantly changing legal, political, and economic history of Colombia has made scholars re-define them time after time as they perceive the real, practical application of resguardos. Therefore, scholars do not have a common position which can describe these lands completely and they understand resguardos from multiple standpoints that have generated constant contradictions and debates in time. This confusion is highly noticeable when we focus in how different are the conceptions of land for the indigenous groups and the government: On the one hand, the indigenous peoples have argued during several decades that the land belonged to them even before the creation of resguardos. Their perspective suggests that these areas given by the crown and the government are neither respected nor protected because, firstly, policies and regulations are not functioning properly and, secondly, because there seems to be an ambivalent position from the government, as it does not act coherently according to what is established in the laws and policies designed for these lands. On the other hand, for governors the lands of resguardos are the property of the indigenous groups; they cannot be interfered with without the authorization of these peoples, and are subject to constant protection by policies and laws.

At the present date, the concept of resguardos has a varied set of different meanings generated from continuous debates and contradictions through time; but, give or take, there are two points of view that separate the opinions stated by all parties: everything is settled under the rule of law, quoting the words of the government, or nothing is solved yet and the government is demonstrating an ambivalent position, citing the perceptions of the indigenous groups. Still today, these contradicting positions remain and the scenario of the conflict is becoming gradually more unclear because scholars, the indigenous groups, and the government have dissimilar standpoints and have not created agreements or a fixed common view. Observing this situation, the analysis in this investigation will consider the perspectives of authors from several different backgrounds and it will categorize them in what I have decided to denominate as the Upper and Lower angles.

The Upper and Lower Angles

This new scheme in the form of angles is the result of the analysis of the works of several different authors, who in their studies defined in different ways the land of resguardos in Colombia. After years of multiple ongoing debates, we have come to the point where these varied arguments will be separated and cataloged according their tendencies in order to contrast them and find whether they have shared characteristics. Therefore, in order to begin, allow me introduce the meaning of these angles and how the authors shall be catalogued.

The Upper Angle

In one hand, we have the Upper angle that conceives resguardos as a category of lands given by a supreme power, the crown, in the times of the colony, and the government, in the republic. This angle conceives these lands as geographical areas that these supreme regimes can give, modify, and remove through legal and political amendments. The authors of this angle argue that the governments have given these lands - currently protected under the rule of law - to the indigenous population and that the communities living there hold two types of rights: 1.) to be consulted before entering or developing industrial activities in these zones; and 2.) to the ownership of the land and its resources by the entire community assented there. Another characteristic of this angle is also observed when the authors assert that resguardos mainly serve in favor of the interests and benefit of the governments.

The Lower Angle

On the other hand, the Lower angle argues that resguardos were mainly designed to benefit the interests of the indigenous communities. It also asserts that the government is not demonstrating its commitment to respect the laws, policies, and the indigenous peoples' collective rights to own and use these zones according to their traditions. Consistent with the standpoints of authors under this angle, the rights of these peoples are neither considered nor respected, as these areas are incessantly becoming the subjects of mining expeditions, sudden occupations, and similar unauthorized activities that: 1.) do not consider the right to previous consultation of the indigenous groups, and 2.) these actions, when performed by other actors and the government itself do not reflect coherence and concordance with the principles established in the legal and political framework designed specifically for these lands.

The Upper and Lower Angles, and the Standpoints Over the Land of the Resguardos

As we saw in the previous sections, from a legal point of view, the current concept of resguardos is still the one consigned in writing. Little can be done to change this condition but, in practice, the definition varies and there have been several authors through time who have searched the reasons behind this in the political and economic backgrounds. When speaking of the resguardos from the political and economic standpoints, the Upper and Lower angles demonstrate a sharper contrast.

The Upper and Lower Angles and the Political Standpoint

The political standpoint examines the reasons behind the creation of resguardos and, simultaneously, it studies the transitions in the governmental regimes and levels of authority that governments and indigenous groups have over these lands. For this reason, let us go deeper into the analysis of the angles examining the variety of arguments and how resguardos were created.

In this standpoint, the Upper angle asserts that resguardos were the result of a strategy designed by the Spaniards, who acted following - and in favor of - the Catholic Church, who throughout the conquest dominated the natives, secularized them, and finally assigned them to live in these areas which accounted for: 1.) an increase in the profits of the crown; and 2.) ensuring the establishment of Catholicism as a dominant religion.

It has come to the attention of Ismael Sánchez that, during the colonization process, the indigenous peoples were socialized in a way consistent with the principles of the Catholic Church. This had been an important authorizing and politically influent organization in the colony and some years at the beginning of the time of the republic (Sánchez, Ismael; 1993, pp. 371-388). In the perspective of this author, through the well-known Papal bulls2 or official ecclesiastical documents, the Church created, authorized, and legitimized not only the conquest activities but also the expansion of the Catholic influence in the territories conquered by the Spaniards (Sánchez, Ismael; 1993, pp. 371-388). One of the most notable Papal bulls that served to justify the Spanish actions, the appropriation of the indigenous territories, their subjugation, and eventually their aggrupation in the resguardos, is the well-known inter caetera (Among Other [Works], in English), dated May 3rd and 4th of 1493. This document establishes, constantly invoking God, that all the territories discovered were meant to become part of the crown for their profitable benefit and that the natives found living there had to be put at the disposition of the principles of the church in order to be converted into Catholics and saved by the Church, the organization in charge of delivering humanity from evil.3

At the time of the colony more Papal bulls were enacted allowing the conquest missions to obtain more lands and generate more revenue for the colonizers, the crown, and, of course, the Catholic church. In this sense, the standpoint from the Upper angle mentions that the crown did indeed gave the indigenous peoples the resguardos, but the purposes were directed towards the maximization of the profit of the crown and the domination of the indigenous communities living there under the principles of Catholicism, religion that still today has a vast majority of followers in Colombia.

In the same Upper angle and standpoint as Ismael Sánchez, David Bushnell also argues that, in the colonial time, Spaniards were always accompanied by representatives of the Catholic church, who, simultaneously with the conquest missions, began to forcefully evangelize the 'savages', in exchange of the payment of tributes to their colonizers (Bushnell, David; 2010, pp. 4 and passim). Therefore, as a starting point, this reveals that there are two authors who share similar views regarding the creation and the origins of the resguardos. These two perspectives, those of Sánchez and Bushnell, not only indicate that these lands were indeed given by the crown but also demonstrate another supreme power was present, aside from the crown itself: the Catholic Church. Through ecclesiastical methods, the Church settled its presence, dominated the indigenous peoples, and ensured the expansion of its ideology in the territory. In this sense from the Upper angle, the resguardos can be considered as the result of a strategy carried out by the Spanish crown and the Catholic Church in which the indigenous peoples were gathered in some areas that facilitated: 1.) the increase of the profits of the colonizers; and, 2.) the expansionism of the religion.

Sánchez focuses his study more on the presence of Catholicism and its expansion in Colombia; unlike him, Bushnell, in a different studied performed along Rex Hudson, deepens his analysis on the examination of the meaning of resguardos. According to them, these areas are conceived as artificially formed land centers that the indigenous peoples could neither sell nor possess (Bushnell, David, and Hudson, Rex. A; 2010, p. 83). Their logic suggests that these areas cannot be sold or owned by the indigenous peoples and indeed, at the time of the colony, these peoples had few freedoms and privileges, which impeded them from using their lands as they desired. Actually, as stated above, the Constitution of Colombia, Law 21, 1991, and Decree 2164, 1995 (among others) are some of the most important legal instruments that recognize the rights of the indigenous peoples to own and use resguardos in a collective way.

Bushnell and Hudson's arguments have perhaps problematized the prolonging disputes and debates over resguardos because, in their conceptions, the indigenous peoples seem to have limited rights over these areas given by the crown and the governments. Therefore, these limitations reflect that, what started as an expansionist strategy of both the crown and the Catholic Church, gradually confined the indigenous groups in resguardos, which seen from this Upper angle, are areas that fully belong to these supreme powers.

In contrast with these perspectives, the Lower angle, asserts that resguardos are the property of the indigenous peoples and were given by the crown for their protection and, regardless of some failures in their functioning, these lands originally belonged originally to them even before the creation of these areas. It is also important to highlight in this angle that some of the authors who could have associated to it have a contradicting perception about the functioning and purposes of these lands.

In the first place, Ocampo López arguments that resguardos are defined as a socioeconomic institution which was designed for the protection of the indigenous peoples who officially started to hold their property rights over them after the agrarian reform of 1591, as it assigned them to live in land areas which became inalienable and communally owned (Ocampo, López. Javier; 1994, pp. 105). Sharing the same point of view, Orlando Fals-Borda says that these lands were indeed given by the Spanish Empire for the protection of the rights of these minorities, who were assigned to live in the rural parts of the country surrounding the cities and newly-formed towns. His argument also affirms, similarly to the authors associated to the Upper angle, that this measure was derived from a congregation policy of the Spanish crown, gathering the indigenous groups in special areas. However, and differently to the aforementioned authors, Fals-Borda thinks that through the creation of the resguardos the crown also gave the indigenous peoples the rights to own and use these fragments of land according to their beliefs and traditions, and, most importantly, the protection from future abuse from colonizers (Fals-Borda, Orlando; 1957, pp. 331-332). Complementing this viewpoint, and in the same angle, He-rreño Hernández argues that the lands of resguardos overlap their existence with legal and political principles in Colombia. In his concept, these areas seek the establishment of a "political affirmation process against institutionality and a differentiation process against other social groups that starts with the delimitation of a territorial domain in which sovereignty, power, and autonomy can be exercised" (Herreño, Hernández. Ángel Libardo; 2004, p. 252). Unlike Ocampo and Fals-Borda, Herreño's argument is focused on the role that these areas play in differentiating the indigenous peoples from the rest of the population by living in a delimited zone where autonomy and sovereignty are present.

These three authors, Ocampo, Herreño, as well as Fals-Borda, coincide in their studies when they explain that these lands given by the crown were designed for the protection of the indigenous peoples, and because of this natives should hold collectively the complete rights over resguardos. At the same time, Herreño, Ocampo, and Fals-Borda contradict the point of view of the Upper angle that sees these areas as the result of a strategy created by the crown and of the Church, designed to increase material wealth and religious followers. Both angles coincide when making reference to the crown as the main giver of these areas. However, the Lower angle does not consider the role of the Catholic Church in this creation process because the authors see resguardos as spaces that were conceded according to the beliefs of the indigenous peoples for their protection against abuse from colonizers. Hence, in the standpoint of the authors of the Lower angle, the Catholic Church is left aside. On the other hand, unlike Sánchez, Bushnell, and Hudson (authors associated to the Upper angle), who argue that resguardos are zones where indigenous peoples have somewhat limited rights, both authors from the Lower angle (Ocampo and Fals-Borda) contradict this point by asserting that these lands are collectively owned by the communities living there and, therefore, they have complete rather than limited rights over them.

Regarding the discussion regarding up to what extend the indigenous peoples and the supreme powers have authority and rights over these areas, authors from the Upper angle, such as David Wallbert, affirm that at the time of the colonization the indigenous peoples neither had a previously established legal system nor a formalized conception about property in order to lawfully claim and having their rights over the land recognized (Wallbert, n.d)). The Spaniards who conquered the Americas refused the possibility to return these whole areas back before the creation of the resguardos for the indigenous peoples and, interpreting Wallbert's argument, these lands belong to the responsible authorities, the crown and the governments, who created the resguardos and gave them to the indigenous peoples. For this author the problem lies on the clash of perceptions because, on the one hand, the indigenous peoples have kept arguing that a vast amount of lands they owned were stolen by the Europeans in the colony and these lands were kept by the governments after the birth of the republic of Colombia, while, over the decades, the indigenous peoples have considered them as not only indigenous traditional property but also as the given resguardos. On the other hand, the colonizers say that from the very moment they conquered the Americas, the lands became their property and eventually were distributed to these natives. The Spaniards also argued that there was no legal system or documents that proved these lands belonged to the natives before their arrival to the Americas. This argument came at a time when the colonization by the crown imposed a legal system, which remains up to certain extent even today, to legitimize their actions, allowing governors to determine the allocation process of indigenous communities in resguardos. In his own words,

European ideas about land and property differed from those of Indians in two important ways. First, under European law, land was a commodity that could be bought and sold, and individuals who "owned" a tract of land had, for the most part, exclusive rights to its use. Second, ownership was determined by formal means, recognized by deeds and contracts, and enforced by courts of law...Europeans [then] took several approaches to obtaining land (Wallbert, n.d).

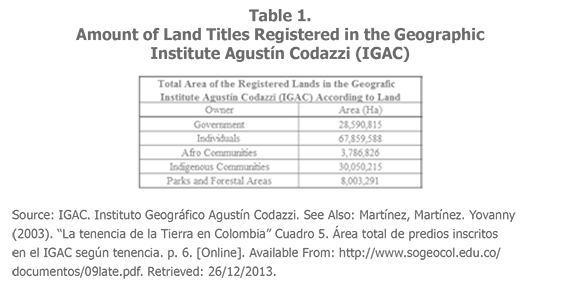

In this line of thought, Wallbert conceives resguardos as belongings of the crown and the governments who devised them, while the indigenous peoples do not share this point of view. According to Wallbert, the rights and, in this case, the authority over the lands of resguardos is determined by the presence of agreements, contracts, laws, policies, etc. However, Wehrmann summarizes this concept in in three points: 1.) the property rights, 2.) the land registration procedures; and, 3.) the reference in the rule of law as the tools that the crown and the government have to determine the owners of the lands. (Wehrmann, Babette. Germany; 2006, Figure 1: Constitutive and Regulative Institutions of the Land Market, p. 2). Unlike Wallbert, Wehrmann affirms that both parties, the crown in the colony and the governments in the republic, constructed an organized legal and political system which made easier for the indigenous peoples to have the rights granted by the concept of resguardos fully recognized and protected. Therefore, speaking in terms of authority over the lands, Wehrmann's logic is more complete than Wallbert's, as she considers the past facts, proofs, and, especially, the presence of a political and legal system as the tools that the supreme powers have to allow or deny the possibility to obtain lands. Complementing this information, Martínez asserts that even the "Organization of American States (OAS) has catalogued Colombia as one of the most advanced countries in regards to having well defined legislation for indigenous peoples" (Martínez, Martínez. Yovanny; 2003, p. 6), because the Colombian legislation has allowed indigenous communities who have their resguardos registered in the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (Geographic Institute Agustín Codazzi), having more than 30,050,215 million hectares distributed across the whole territory, as seen in the following chart.

In the perspectives of these authors, in order to give the resguardos to the indigenous groups there is a constructed legal and political machinery that responds to the needs of these peoples and works properly to address their claims. According to this standpoint, the existence of: 1.) institutions with capacity invested by the governments in Colombia; and 2.) land registration procedures, contracts, property titles, official agreements, and decrees and laws, accounts for the existence in Colombia of a functioning process to determine the assignation of resguardos to the indigenous peoples. These authors affirm that still to this date, these organizations4 and processes are operating properly.

While the authors of the Upper angle assert that the crown and the governments established the legal and political machineries that have permitted the indigenous peoples to have their resguardos, the authors of the Lower angle discuss that these machineries and processes do not seem to be working efficiently because: 1.) there is no clarity regarding how many communities have their lands registered; and 2.) the rights that these communities hold have been ignored by the crown and the governments themselves throughout history. This Lower angle standpoint affirms that the organizations, ministries, and similar dependencies over which the government has invested its power are constantly contradicting each other, ignoring in unison the indigenous rights and authority over resguardos.

One of the most notable authors from the Lower angle and standpoint is Martti Koskenniemi who affirms that "there can be no real doubt ... of the superiority of the Spanish [and governments] over the indigenous peoples, as well as over their right to penetrate indigenous territories for the purpose of trade and proselytizing" (Koskenniemi, Martti; 2009, p. 5). The resguardos, in his perspective, have always been flexible land areas easily penetrated by the supreme powers that, without any previous consultation to the indigenous peoples to enter into their territories, violate their authority and their property rights. Koskenniemi, as well as the natives, argue that the concept of resguardos has always been unclear and misconceived, even by the authorities of the government (Koskenniemi, Martti; 2009). The government, according to the indigenous peoples, enters into these zones without acknowledging the presence and rights of these minorities, destroying their environment and putting their lives under risk, while simultaneously developing unstoppable mega infrastructure projects, mining activities, and military operations in these lands. For Fabio Alberto Ruiz these areas are conceived as:

an institution...[which] at least in legal matters meant an important recognition of the political rights of indigenous groups as subjects owners of the land, that also allowed them a space to preserve their cultural traditions. However, this principle was reduced to be only on paper because, in a more specific area, one of its effects was to confine the indigenous communities in terms of space,, ridding them of the best lands, situation that constructed...the land tenure tendency towards latifundium-smallholding that characterizes the country even today (Ruiz García, n.d).

Ruiz's opinion of resguardos deals with a very important topic related to the reduction of the nature, function, and purpose of these lands to some lines written in paper, since the original intended purpose of these areas is not evidenced in reality. Unlike Koskenniemi, who focuses his attention on the frailty of the authority of the indigenous peoples over their resguardos, and how they were degraded to being considered as tools used by the crown and the government for the generation of income, Ruiz argues that the governments have used the concept of resguardos to project an illusion of protection over the indigenous groups, while actually taking away their best lands and establishing an unequal land tenancy pattern that privileges private companies and big landowners instead.

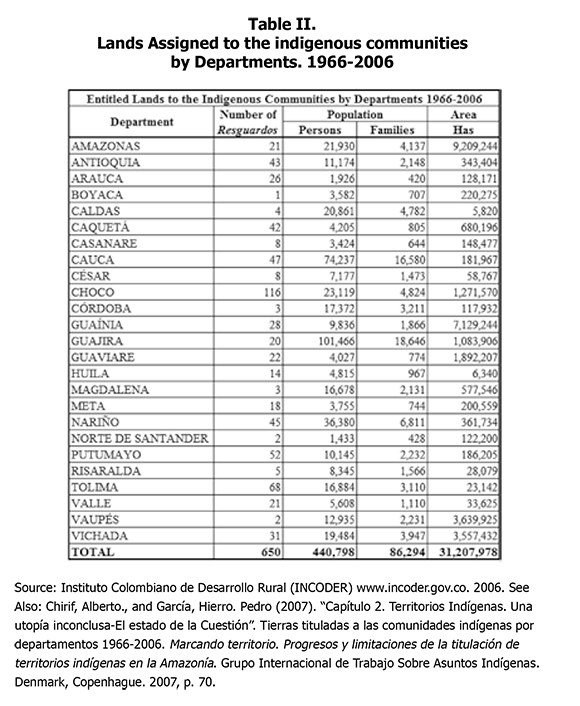

Alberto Chirif and Pedro García Hierro, who based their study on official information of the INCODER, argued that the number of hectares of land given and registered in the form of resguardos to the indigenous peoples is 31,207,978 million hectares, as it can be seen in the graphic following these lines (Chirif, Alberto., and García, Hierro. Pedro; 2007, p. 70). This total number exceeds by 1,157,763 million hectares the total stated in the Upper angle by Martinez, who based his information on the data of the IGAC. However, Ruiz, who based his conclusions on the data obtained from the DANE, contradicts Martínez from the Upper angle, and Chirif and Hierro from the Lower. According to his study "currently there are 710 assigned resguardos located in 27 departments and 228 municipalities of the country, occupying approximately 34 million hectares, equivalent to the 29.8% of the total extension of the country" (Ruiz García, n.d.). His results surpass by more than 3 million hectares the total presented by Chirif and Hierro, and by around 4 million hectares the result of the study of Martínez.

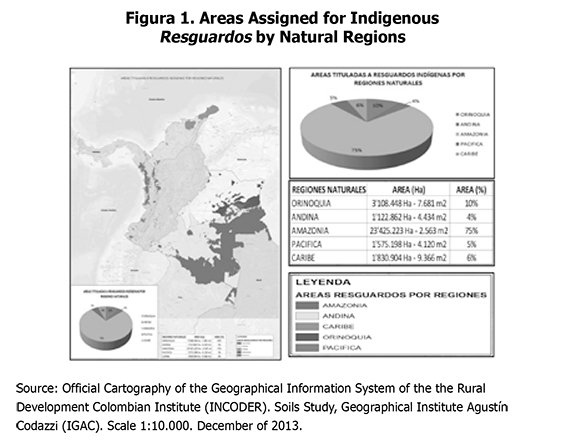

Every author, from both angles, does not agree on the total number of hectares assigned in form of resguardos. Each dependency from the government may have different data and for this reason the results may generate more contradictions among authors, and of course, between the indigenous groups and the government. In the most recent geographic update of the resguardos, carried out by the INCODER in December of 2013, the total number of hectares of resguardos was approximately 31,062,635 million hectares, out of which the Amazonia region holds the majority of resguardos with a 75%, and the Andean region the lowest with 4%, as it is can be see in the following map and data:

These contradictions are making the scenario for understanding resguardos ambiguous for scholars, indigenous groups, and the government. The endless debates among authors regarding the analysis of resguardos are becoming more complex, considering the different amounts of standpoints and, as shown in the next section, the opinions of writers as well as those of the indigenous peoples and the government remain divided. Meanwhile, from the Upper angle, resguardos are seen as mere potential zones for generating development and revenues and, contradicting this argument, the Lower angle sees them as spaces not for the generation of profit, but for the preservation of the patrimony, the traditional roots of the country, and the indigenous peoples.

The Upper and Lower Angle and the Economic Standpoint

As as starting point for this category, Germán Colmenares affirms that resguardos, as seen from this standpoint, were created as a strategy of the Spanish crown, who gathered the natives in some concentrated and specific areas all over the territory, in order to stimulate the economy and the extraction of natural resources (Colmenares, Germán; 2001, p. 117). His perspective is similar to the arguments of Sánchez, one of the authors mentioned at the political standpoint in the Upper angle, who argues that these lands were created by the crown and the Catholic Church in order to get more revenue by making the indigenous peoples their slaves and religious followers.

When the Spaniards arrived to the Americas, they searched for precious stones, such as emeralds, and metals such as silver, gold, and copper in order to increase the material income of the colonizers, using the indigenous peoples as workforce. The Spaniards not only sought to ensure complete profit and gather more natural resources by making indigenous peoples exploit the territory but also made them harvest the land in order to generate progress by incentivizing a market economy based on farming and the extraction of raw materials.

In this sense, Colmenares sees these lands as strategic points that the crown and, currently, the government, have been using to develop the economy. As a complement to this idea, one of the most recognized authors in Colombia, well-known for his economic background and reflective position towards resguardos, Salomón Kalmanovitz, argues in one of his several studies about the economy of the colony and the republic that resguardos were considered as indigenous peoples confinement zones "that were adequate land extensions that provided ways to gather sustenance for the indigenous communities, from which available working labor force was "distributed"" (Kalmanovitz, Salomón; 2008; p. 46). Colmenares and Kalmanovitz both see that the existence of these lands provided not only resources but also working force for the interests of the crown and the government. At this point, Absalón Machado, another well-recognized Colombian economist, refutes Colmenares and Kalmanovitz' ideas because, in his perspective, resguardos seem to be inexistent after, during the colony and several years of the republic, diverse parties like farmers, landowners, and others, assumed control of the areas and the resources, making this type of land barely visible even today. In his own words, " resguardos disappeared all across the country since 1850, even though in the south area of Colombia they still exist ...due to the presence of a poor capitalist development and an agricultural economy that did not manage to generate exportation crops due to the lack of communication roads" (Machado, Cartagena. Absalón; 2009, p. 49). Machado's arguments suggest that the lands of resguardos seem to have completely vanished from Colombian soil and perhaps this is because, despite the presence of some indigenous communities, the parties which appropriated these areas, or that still have them under their power, have already used them completely, depleting their resources, converting them into unusable geographic areas for the indigenous peoples.

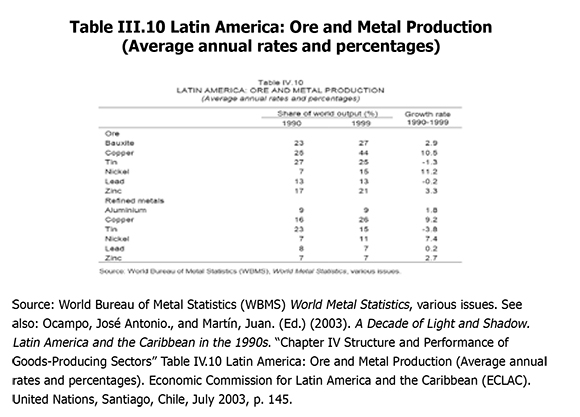

Machado's position reflects in some way a part of the reality that is currently present in Colombia, even years after becoming an independent country from Spain; a reality in which land is seen as a powerful wealth and those who have it under control hold the capacity of generating more income. The current economic model in the world highly valuates and constantly demands non-renewable resources, such as precious stones and metals such as emeralds, gold, silver, copper, among others. In the following charts we can observe some interesting data that is relevant for this study and especially for the standpoint of this angle. In the first chart we can observe how non-renewable resources, such as metals, gradually became relevant for the economies and especially when examining the share of the global copper output, which had a 19% increase between 1990 and 1999.

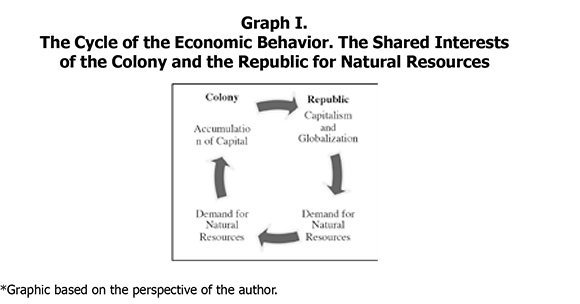

The following graphic presents how the economic behavior of the colony is similar to the one of the republic. In both periods land is conceived as a potential source of income in which the presence of the indigenous peoples and their rights over resguardos come after the profit obtained from natural resources.

The authors defending the Upper angle seem to privilege the economic growth over resguardos and the rights of indigenous peoples. These lands, possessing abundant non-renewable resources, are considered to be potential zones for the generation of profit and development. However, these areas still exist and it because of this that Machado's argument is not shared by the authors of the Lower angle. For this reason, the writers presented in the final section of this analysis as part of the Lower angle not only contradict the arguments given by Colmenares, Kalmanovitz, and Machado but also attempt to demonstrate that the economic behavior of the government is another of the reasons causing the conflict with the indigenous peoples, who defend their lands and are opposed to these economic behaviors.

The Lower Angle and the Economic Standpoint

Opposed to Colmenares and Kalmanovitz, whose idea of the creation of these land areas highlights an economic strategy, and supporting the conception of the indigenous groups, Shelton Davis, Enrique Sánchez - with the collaboration of María Valdés - argue that resguardos are the living territories of the indigenous peoples and are not limited to be the places of vital importance for development due to the allocation of natural resources and variety of soils. In these authors' perspective, resguardos are geographical portions which are vital for the patrimony because they not only preserve the cultural roots of the nation but also the ecosystem through the management indigenous peoples have given to them (Davis, Shelton., Sánchez Enrique., and Valdés, María; 2003, p. 804 and passim). These lands, in the perspective of these authors, hold a religious and spiritual conception5 that the communities allocated there use to define their customs and traditions, which do not seek the generation of revenue based on the exploitation of natural resources such as emeralds, gold, silver, copper, and oil6 as the government would. Opposing to Colmenares, Kalmanovitz, and Machado, Arango and Sánchez argue that resguardos "for some of the indigenous communities have a very deep cultural meaning. It is not simply a productive factor, neither a good for trading... it is a topic related to the ancestral territory, their own territory" (Arango, Ochoa. Raul., and Sánchez, Gutierrez. Enrique; 2004, p.103). For the authors of the Lower angle, resguardos as same as the resources that do not have an economic value because, in the logic of the indigenous peoples, these elements are part of an ecosystem where their deities are also manifested.

In comparison to the Upper angle, García Hierro and Surralés manifest that, in order to understand the conception of the land for the indigenous peoples, multiple elements come into the picture. According to the arguments given by these authors, the territory where the natives live, aside from being considered as an area established for their preservation and protection, providing them with the necessary elements for their daily lives, is also considered as "a space for social relationships with each one of the elements of the ecosystem. Relationships, networks, channels, paths, etc.; the territory is not a finite area shaped by the inherent limits to its existence but a fabric in the process of constant constitution and reconstitution" (García, Hierro. Pedro., and Surralés, Alexandre; 2005, p. 20). All the authors presented in this angle share a common standpoint related the land of the indigenous peoples as areas that work to preserve the ecosystem, as it was highlighted by Shelton, Sánchez, with the collaboration of Valdés. Also, different to the three previous researchers, authors like Arango, Sánchez, Gutierrez, García Hierro, and Surralés attempt to demonstrate that in the lands of the resguardos there is a presence of a divinity that gives a spiritual rather than economic value to the indigenous peoples, who consider these lands as the givers of life.

The current government has given priorities to the preservation of these areas in the National Development Plan (National Planning Department (DNP). National Development Plan (2010-2014). Santos, Calderón. Juan Manuel. "Prosperity for Everyone"). Nonetheless, the actions towards them reflect the fact that there is a gap between what is stated in the law, along with the political principles, and the actions performed by the government, such as unauthorized invasions, carrying out mining activities, construction of infrastructures in the search for development, and the destruction of the ecosystem when the government does not previously consider the rights of the indigenous over these lands.

Conclusions

In this article we examined the reasons and arguments presented by the government, the indigenous groups, and different authors from several backgrounds over the lands of resguardos, diving them in two angles, the Upper and the Lower. After contrasting these opinions, it is evident that there are few shared points over which authors coincide but, overall, there is neither a consensus among scholars nor between the indigenous peoples and the government about resguardos. The political and economic standpoints were understood as the elements that change and have an impact on the creation and the enactment of the law, the component which establishes rights, equality, and fairness for the whole population.

This conflict over resguardos is presented not only because of the clash of interests between the indigenous groups and the government but also because there is an evident gap between what is enacted in the political machinery and reality. As mentioned throughout this document, the actions performed by the governmental authorities are not considering the rights of the indigenous peoples over these lands, which were originally created for the protection of these communities and the preservation of the cultural roots of the country.

Therefore, as long as this gap persists, along with the differences in the perspectives over the land between the indigenous peoples and the government, the absence of agreements and the lack of a common position that integrates these perspectives and interests into one, will continue to prolong this conflict that still is present after it began over 400 years ago.

Pie de página

1In this sense, inalienable means that a property cannot be sold; imprescriptible means that a property or a possession is not lost in time; and indefeasible denotes a situation in which a judge cannot disposes a property or wealth completely. For more information regarding these concepts, see also: The Colombian Constitution of 1991, Articles 63, 329, and 330.

2The Church through the power invested on the Popes, was the political actor responsible for the influence over several crowns to act and proceed according to its holy interests. These spin around the attempt at saving the world from pagan religions and demoniac beliefs by expanding its range of influence through conquest activities mostly carried out by Spain. For further information about the Papal bulls and their characteristics and consequences, please refer to: Papal Encyclicals [Online]. Available From: http://www.papalencyclicals.net/all.htm

3Alexander VI. May 4, 1493. Inter Caetera. In: Papal Encyclicals [Online]. Available From: http://www.papa-lencydicals.net/Alex06/alex06mter.htm

4Organizations such as the ministries, official dependencies, and delegated corps such as: Catastro (Real-Estate Registration Central Agency), the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (Geographic Institute Agustín Codazzi (IGAC)), the Departamento Nacional de Planeación (DNP) (National Planning Department), the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE) (National Statistics Administrative Department), the Instituto Colombiano de la Reforma Agraria (INCORA) (Colombian Agrarian Reform Institute), currently known as the Instituto Colombiano de Desarrollo Rural (INCODER) (Rural Development Colombian Institute), among others, are the most notable and important official authorities established by the government to determine the owners of the land.

5The religions of the indigenous peoples are very challenging to define in general terms because each community in every resguardo have their own beliefs, and even though those are shared up to certain extent, they diverge according to the perspectives of each group. For the indigenous peoples, every natural resource and element of the territory has its purpose, essence, and reason to exist according to their beliefs.

6The groups conceived inside a resguardo strongly believe that there is a supreme force that cannot be disrespected by exploiting territories as the colonizers and governments have done. This force that rules and defines their existence emanates from the environment which surrounds them and when this ecosystem is preserved, it maintains alive the essence of the indigenous peoples along with their lifestyle, based mostly on the agriculture, stockbreeding, and harvesting.

References

Primary Sources

Colombia, National Congress of the Republic. Ministry of Internal Affairs. (1991, March 4th). Law 21 of 1991, March 4th. "Through which it is Approved the Convention Number 169 About the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent countries, adopted by the 76th Reunion of the General Conference of the International Labor Organization (ILO), Geneva, 1989". In: Official Diary No 39720 of March 6th, of 1991. [ Links ]

Colombia. Agriculture Ministry (1995, December 7th). Decree number 2164 of 1995. "whereby it is partially regulated the Chapter XIV of the Law 160 of 1994 in what is related to the dotation, adjudication and land entitlement to the indigenous communities for the constitution, restructuring, enlargement and quiet title action of the indigenous resguardos in the national territory". In: Official Diary No 42.140, of December 7th of December 1995. [ Links ]

National Planning Department (DNP). National Development Plan (2010-2014). Santos, Calderón. Juan Manuel. "Prosperity for Everyone ". Departamento Nacional de Planeación. Todos por un Nuevo país [Online] Available From: https://www.dnp.gov.co/Plan-Nacional-de-Desarrollo/PND-2010-2014/Paginas/Plan-Nacional-De-2010-2014.aspx [ Links ]

Text of the Constitution of Colombia (1991). Title II. Concerning Rights, Guarantees, and Duties. Chapter 2. Concerning Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights. Article, 69. pp. 19. [Online]. Available From: http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/colombia_const2.pdf [ Links ]

Text of the Constitution of Colombia (1991). Title XI Concerning the Territorial Organization. Chapter 4. Concerning the Special Regime. Article, 329-330. pp. 111-112. [Online]. Available From: http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/colombia_const2.pdf [ Links ]

Secondary Resources

Arango, Ochoa R. y Sánchez Gutiérrez, E. (2004). Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del nuevo milenio: población, cultura y territorio. Bases para el fortalecimiento social y económico de los pueblos indígenas. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación. [ Links ]

Bushnell, D. (2010). Historical Setting. In: R. A. Hudson, (Ed.). Colombia: A Country Study (pp. 1-63). Washington DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. United States Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Bushnell, D., and Hudson, R. A (2010). The Society and Its Environment. In: R. A. Hudson (Ed.), Colombia: A Country Study (pp. 63-133). Washington DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. United States Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Chirif, A., and García Hierro, P. (2007). Marcando territorio: progresos y limitaciones de la titulación de territorios indígenas en la Amazonía. Copenhague: Grupo Internacional de Trabajo Sobre Asuntos Indígenas. [ Links ]

Colmenares, G. (2001). La economía y la sociedad coloniales, 1550-1800. In: Á. Tirado Mejía (Eds.), Nueva historia de Colombia (vol. 1, pp. 117-153). Bogotá: Planeta. [ Links ]

Copland, A. (1978). La estadística durante la colonia española. En Historia de la estadística en Colombia. 1900-1990. Bogotá: Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Online Publication in the in the website of the Republic Bank's Library Luis Angel Arango. [ Links ]

Davis, S., Sánchez, E., and Valdés, M.A (2003). Indigenous Peoples and Afro-Colombian Communities. In: M. Giugale, O. Lafourcade y C. Luff (Eds..), Colombia theEconomic Foundation of Peace (pp. 787-824). Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank. [ Links ]

Duncan, G. (2006). Los señores de la guerra. Bogotá: Planeta. [ Links ]

Fals-Borda, O. (1957). Indian Congregations in the New Kingdom of Granada: Land Tenure Aspects, 1595-1850. The Americas, 13(4), 331-351. [ Links ]

Fajardo Montaña, D. (2002). Para sembrar la paz hay que aflojar la tierra: comunidades, tierras y territorios en la construcción de un país. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Estudios Ambientales. [ Links ]

García, Hierro. Pedro., and Surralés, Alexandre (2005). The Land Within. Indigenous Territory and Perception of Environment. Skyve, Denmark. 2005. ¿Cuál de las dos formas hay que referenciar? Teniendo en cuenta las citas en el texto, yo pienso que en la referencia debe ir de esta forma. [ Links ]

Giugale, M., Lafourcade, O. y Luff, C. (Eds.) (2003). Colombia: The Economic Foundation of Peace. Washington DC: World Bank Publications. [ Links ]

Herreño Hernández, Á. L. (2004). Evolución política y legal del concepto de territorio ancestral en Colombia. El Otro Derecho, 31-32, 247-273. [ Links ]

Kalmanovitz, S. (2008). La economía de la Nueva Granada. Bogotá: Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano. [ Links ]

Koskenniemi, M. (2010). Colonization of the "Indies": The Origin of International Law? En Y. G. Chopo (Eds..), La idea de América en el pensamiento ius internacionalista del siglo XXI (pp. 43-64). Zaragoza: Institución Fernando El Católico. [Online]. Available From: http://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/30/12/05koskenniemi.pdf [ Links ]

Hudson, R. A. (2010). Colombia: A Country Study. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Machado, A. (2009). Ensayos para la historia de la política de tierras en Colombia: de la Colonia a la creación del Frente Nacional. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

Newson, L. A. (2006). The Demographic Impact of Colonization. In: V. Bulmer-Thomas, J. Coatsworth y R. Cortes-Conde (Eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America (pp. 143-184). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ocampo, J. A. y Martin, J. (Eds.) (2003). A Decade of Light and Shadow: Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1990s. Santigo de Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. [ Links ]

Ocampo López, J. (1994). Historia básica de Colombia. Plaza & Janés. [ Links ]

Sánchez Bella, I. (1993). Las bulas de 1493 en el derecho indiano. Anuario Mexicano de Historia del Derecho, 5, 371-388. [ Links ]

Tirado Mejía, Á. (Eds..) (2001). Nueva historia de Colombia. Bogotá: Planeta. [ Links ]

Web Resources

Alexander VI. May 4, 1493. Inter Caetera. In: Papal Encyclicals [Online]. Available From: http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Alex06/alex06inter.htm [ Links ]

Papal Encyclicals. [Online]. Available From: http://www.papalencyclicals.net/all.htm [ Links ]

Martínez Martínez, Y. (2003). La tenencia de la tierra en Colombia. Bogotá: Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi. [Online]. Available From: http://www.sogeocol.edu.co/documentos/09late.pdf [ Links ]

Ruiz García, F. A. (n.d.). La construcción de la territorialidad para los grupos étnicos en Colombia. Revista de la información básica, 1(2). [Online]. Available From: http://www.dane.gov.co/revista_ib/html_r2/articulo7_r2.htm [ Links ]

Wallbert, D. (n.d..). Colonial North Carolina. Colonial (1600-1763). North Carolina History: A Digital Textbook. UNC, School of Education. [Online]. Available From: http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-colonial/2027 [ Links ]

Wehrmann, Babette (2006). Cadastre in Itself Won't Solve the Problem: The Role of Institutional Change and Psychological Motivations in Land Conflicts - Cases from Africa. In: FIG International Federation of Surveyours. [Online] Available From: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.521.7467 [ Links ]

Other Resources

Official Cartography of the Geographical Information System of the the Rural Development Colombian Institute (INCODER). Soils Study, Geographical Institute Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). Scale 1:10.000. December of 2013. [ Links ]