Introduction

Lobsters of the family Nephropidae are of great commercial importance in many fisheries around the world (Cobb & Wang 1985, Holthuis 1991), and can be found from shallow waters to 1,400 meters depth on sand and mud bottoms (Tavares 2002). Within this family is the genus Metanephrops distributed in the Indo-Pacific, Eastern Pacific and Western Atlantic (Holthuis 1991, Chan et aL 2009, Robey et al. 2013). Some species of this genus have been reported as being of great economic importance such as Metanephrops mozambicus (Macpherson 1990) caught by industrial fisheries in East Africa (Robey et al. 2013), Metanephrops japonicus (Tapparone-Canefri 1873) which presents a high value in local fisheries of Japan (Okamoto 2008) and Metanephrops binghami (Boone 1927) that has potential for exploitation in Venezuelan waters (Gómez et al. 2000, Gómez et al. 2005).

On the continental slopes of north-west Australia, three deep-sea crustaceans of the genus Metanephrops are exploited commercially: M. boschmai (Holthuis 1964), M. andamanicus (Wood-Mason 1891) and M. australiensis (Bruce 1966; Ward and Davis 1987; Wassenberg and Hill 1989). In addition, in New Zealand a deep-sea lobster fishery has been developed targeting scampi (M. challengen Balss 1914; Smith 1999).

The deep-sea Caribbean lobster (M. binghami) has a wide distribution from the Bahamas Islands to French Guiana, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, inhabiting depths ranging between 200 and 700 m (Holthuis 1991, Tavares 2002). Research on deep water in the Colombian Caribbean has reported the potential of M. binghami for a fishery with high commercial value, but at present there is no fishery for this species and there is no information about its biology, population dynamics and life history (growth, reproduction, etc.) (Paramo & Saint-Paul 2012). However, for the management of fisheries it is very important to know the size structure, body growth and size at sexual maturity of commercially important species (Hilborn & Walters 1992), which influence the structure and function of marine ecosystems (Haedrich & Barnes 1997, Shin et al. 2005). Therefore, the objective of this study is to provide biological information on size structure, size at sexual maturity and morphometric relationships of the deep-sea Caribbean lobster Metanephrops binghami in the Colombian Caribbean.

Materials and methods

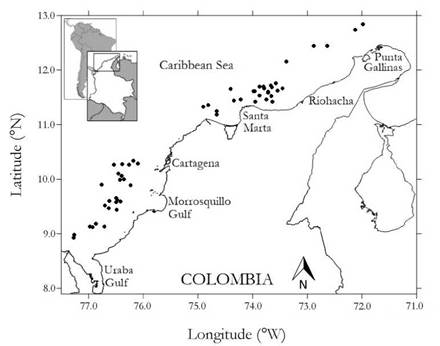

Sampling was carried out in November and December 2009. Samples were taken by trawling (30 min haul duration) in depths ranging from 200 to 550 m, with at least two hauls per 100 m depth stratum, in the Colombian Caribbean. We used a commercial FURUNO FCV 1150 echo-sounder with a transducer at a frequency of 28 kHz to trawling locations, with a total of 87 stations sampled (Figure 1). Samples were collected by a commercial shrimp trawler using a trawl with a cod-end mesh of size 44.5 mm from knot to knot (Paramo & Saint-Paul 2012).

Fig. 1 Study area. Dots indícate the location of sampled stations during the survey in the Colombian Caribbean.

In the laboratory, the Caribbean lobster (M. binghami) specimens were measured using twelve morphometric measurements of the body to the nearest 0.01 mm, total wet weight (W) to the nearest 0.01 g, and sex was determined. The morphometric variables recorded were: (1) total length (TL), (2) antennal spine width (ASW), (3) hepatic spine width (HSW), (4) cephalothorax length (CL), (5) diagonal cephalothorax length (DCL), (6) first abdominal segment length (FSL), (7) first abdominal segment width (FSW), (8) first abdominal segment height (FSH), (9) second abdominal segment length (SSL), (10) sixth abdominal segment height (SISH), (11) tail length (TaL) and (12) head length (HL) (Tzeng et al. 2001, Tzeng & Yeh 2002, Paramo & Saint-Paul 2010).

Differences in sizes and weights between females and males were analyzed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (a = 0.05). The length frequency distributions for females and males allowed calculating the sex ratio by size class (each 10-mm length interval). A chi-square test was performed to establish significant differences between the total number of females and males and by size class with a reference of 50 % sex ratio. Additionally, a Generalized Additive Modelling (GAM; Hastie & Tibshirani 1990) was used to analyse the relation between the sex ratio and size class.

We used spline (s) smoothing with a Gaussian family to estimate the nonparametric functions. The probability level of the nonlinear contribution of the nonparametric terms was made with the significance value (P) for judging the goodness of fit (Burnham & Anderson 2003).

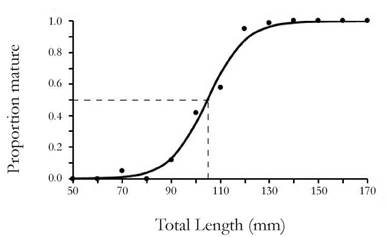

The maturity of M. binghami was evaluated considering five macroscopic maturity stages for females. The ovary staging was based on the colour, according to Paramo & Saint-Paul (2012): stage 1, white-immature; stage 2, opaque-in development; stage 3, yellow-maturing; stage 4, green-mature; stage 5, ovigerous female carrying eggs on its pleopods (adapted from Mente et al. 2009). We considered stages I and II as immature and stages III, IV and V as mature. The proportion of mature individuals in each 10-mm length interval was recorded and modelled using a logistic function. To obtain an estimate for size at sexual maturity (TL50 %) we fitted the curve by least- squares minimization using a nonlinear regression.

Where P(TL) is the mature female proportion, a and b are the parameters estimated and TL is the total length. The size at 50% maturity is obtained by TL50 % = (-a/b) (King 2007).

To analyse the onset of sexual morphological maturity in females and males, the total length and cephalothorax length were established as primary morphometric measurements, relating it to each of the different measures (Ql- et al. 2013). A regression model with segmented relation of the segment package was used (Muggeo 2003, 2008). This model is based on the relations between two explanatory variables that are represented by two straight lines connected by a break point (Muggeo 2003, 2008). The fitting is based on the minimization of the gap parameter, which measures the space between the two regression lines on each side of the break point. When the algorithm converges, the "gap" parameter approaches to zero, minimizing the standard error of the break point (Muggeo 2008). The breaking points of the relationships between the two morphometric measurements were considered as indicative of the size at the beginning of maturity for females and males as long as the break points for which the value of t associated with the "gap" parameter were lower than two (Muggeo 2008). In addition, the Davies test was used to test significant differences between the slopes of the fitted segments (Davies 1987, Muggeo 2008, Queirós et al. 2013, Williner et a. 2014).

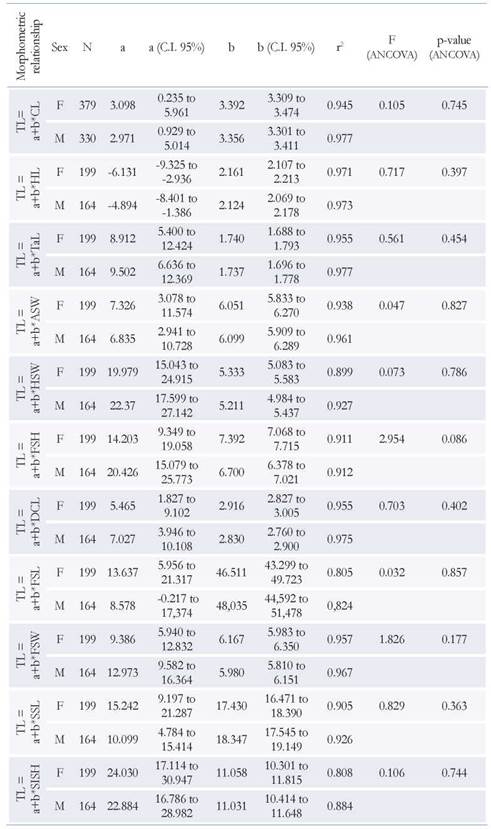

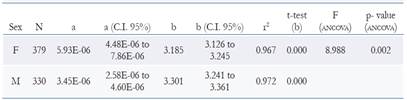

The length-weight relationship was modelled as a power law equation by regression of weight vs length W = a Lt b by logarithmic transformation ln W = ln a + b ln Lt where Wis the total weight in g, TL is the total length in cm, a is the intercept and b is the allometry coefficient. As a measure of fit goodness, the determination coefficient (R2) was used. The confidence interval of 95 % for b was estimated and t-student test was conducted to determine if the lobster presented isometric growth (H0: b = 3, a = 0.05). The morphometric relations were performed using least squares fitting to linear equation Y = a + X*b where; a (intercept), b (slope), Y for TL and X for the independent variables (ASW, HSW, CL, DCL, FSL, FSW, FSH, SSL, SISH, TaL and HL). To evaluate differences in linear relationships between the sexes an analysis of covariance was performed (ANCOVA) (Zar 2009).

Results

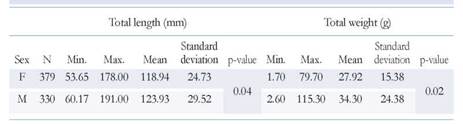

The size of M. binghami females ranged between 53.65 and 178.00 mm TL (mean 118.94 ± 24.73 mm) and the size of males ranged between 60.17 and 191.00 mm TL (mean 123.93 ± 29.52 mm). The weight of females ranged between 1.70 and 79.70 g (mean 27.92 ± 15.38 mm) and the weight of males between 2.60 and 115.30 g (mean 34.30 ± 24.38 g). Statistically significant differences in size and weight (p < 0.05) between sexes were found (Figure 2, Table 1); females were smaller than males.

Fig. 2 Total length frequency distributions of M. binghami (mm) by sex for total area, north area and south area.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of total length (mm) and total weight (g) of females (F) and males (M) of M. binghami.

The sex ratio showed significant differences (p < 0.001) between the total number of females and males and per size class when compared with a 50% of sexual ratio. However, there was no significant difference (p = 0.067) between the number of females and males in the size range of 70 to 140 mm of total length. Females showed a larger proportion in sizes smaller than 65 mm of total length (p < 0.001). Then, the sex ratio decreased favouring males in sizes ranging from 145 and 190 mm TL (p < 0.001) (Figure 3a). The GAM nonlinear fitting was significant (p = 0.000) showing a deviance explained of 88.7 % and the relation between sex ratio and total length (r2 = 0.839) shows that this species sex ratio decreases according to total length in the Colombian Caribbean (Figure 3b).

Fig. 3 a) Sex ratio of Caribbean lobster (M. binghami) in the Colombian Caribbean, b) relation between sex ratio and total length obtained by GAM models with spline smoother, continuous line: fitted valúes, dotted line: confidence intervals.

The size at sexual maturity (TL50 %) of females was 104.56 mm of TL (31.3 % immature and 68.6% mature) (Figure 4). The parameters of the logistic model were a = 13.613 and b = -0.130, r2 = 0.99. Estimates of the break points or beginning of morphometric maturity were performed for all the relationships. However, only the values shown in Table 2 correspond to those estimates that showed significant differences between the slopes (Test Davies, p < 0.05) and values where the break point analysis showed consistency at the moment of varying the range of the initial value in the algorithm "segment". The slopes of juveniles (first segment) were always higher than adults. However, for the relationship (HSW vs TL) in males, the slope of adults was higher than juveniles. The break points found for HL, FSH, SISH vs TL in females were similar. Those performed by the segmented regression with CL as the main measure, ranged from 31.5 to 37.7 mm. For males, the estimated break points with TL ranged from 104.40 to 119.2 mm and those estimated with CL between 43.4 to 44.8 (Table 2).

Table 2 Results of the break point estimated by segmented regression for each morphometric relationship in males and females of M. binghami. The intercept and slope are presented for each segment. J: juveniles and A: adults.

The relationships of total weight with total length for both females and males were significant (p < 0.001) and weight variability is explained by about > 90 % for both sexes (Table 3), showing a positive allometric growth (b > 3), where the weight (W) increases to a greater proportion than the size. ANCOVA showed that there are significant differences between the slopes of females and males in the weight- length relationship (Table 3; Figure 5a). The morphometric relationships between TL vs ASW, HSW, CL, DCL, FSL, FSW, FSH, SSL, SISH, TaL and HL showed high determination coefficients (r2 > 0.80), indicating a high correlation between sizes. The ANCOVA showed that there is no statistically significant difference between the parallelism of the slopes of females and males in all linear relationships (Table 4; Figure 5 b-l).

Table 3 Descriptive statistics of total length (mm) and total weight (g) of females (F) and males (M) of M. binghami.

Discussion

Deep-sea lobsters have a high commercial value in international markets, and there are many fisheries targeting these crustaceans (Holthuis 1991, Bell et al 2013). Our results show that the sizes of M. binghami are similar to those reported for other congeners such as M. mogambicus, which is captured in East Africa by the industrial fishery with a cephalothorax length of 45 mm (Robey 2013) and is commercialized at a higher price than the spiny lobster (Chan & Yu 1991). M. japónicas, known as Japanese shrimp, with a total length of 200 mm, has a high economic value, and is a fishery of commercial importance in the Bay of Suruga in Japan where there is a small stock that is subject to high fishing pressure (Okamoto 2008). M. binghami is found in Venezuelan waters with a total length of 206 mm and is reported as having potential for a new fishery (Gómez et al. 2000, Tavares 2002, Gómez et al. 2005).

In the present study, females of M. binghamiwere smaller than males, similarly to that reported for M. rubellus (Moreira 1903) which shows sizes ranging from 71.3 to 177.7 mm of TL in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil (Severino-Rodrigues et al 2007), (Severino-Rodrigues et al. 2016). For more than two decades M. rubellus has been captured in the landings of pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeuspaulensis and F. brasiliensis) in Brazil with sizes ranging from 65 to 186 mm TL (Severino-Rodrigues 1997, 2016).

Some causes that have been considered in the changes of sex ratio with the size have been the differential mortality, the greater activity of one sex in the reproductive period, the food restriction and the use of different habitats by the two sexes (Company & Sarda 1997, Koeller et al. 2000, Charnov & Hannah 2002, Chiba et al. 2006, Ayza 2010, Ayza et al. 2011, Grabowsky et al. 2014). The reason of the change in sex ratio with size may respond to sexual differences in growth, mortality, or migration (Siegel et al. 2008). In fact, differences in natural mortality between sexes are a factor that contributes potentially to the unequal sex ratio (Wenner 1972). In this sense, if the rates of growth and mortality of males and females were the same, the sex ratio should remain constant; on the contrary, for increases and reductions in certain size classes, there must be differences in growth rates between females and males. Therefore, the pattern of sex ratio is a result of the mixed effects of differences in growth rates between males and females, mortality rates and age composition (Siegel et al. 2008. The size at sexual maturity is used as a parameter to establish minimum sizes of catches. Therefore, biological research is required to know the reproductive cycle and the factors that affect the success of spawning, which are necessary for the management of fisheries. In Brazil, the size at sexual maturity of females of M. rubellus was 82.5 mm in total length (Severino-Rodrigues et al. 2016), which is lower than that reported for M. binghami (104.56 mm in total length) in the Colombian Caribbean. Queirós et al. (2013) consider that total length and cephalothorax length are good predictors for estimating the break point. The size at the beginning of maturity in females estimated from the morphometric data was slightly higher than that estimated with the logistic function. Records of ovigerous females may be underestimated due to the burying behaviour during rest when light increases (Paramo & Saint-Paul, 2012). In the present study, the first abdominal segment height (FSH) in females had a very close relation with the size at sexual maturity estimated with the logistic function (TL50 % = 104.56 mm and FSH vs TL = 106.031 mm TL). In the same way, the size at the beginning of maturity estimated by morphometry, taking CL as the primary variable, resulted in a break point (FSH vs CL = 33.797 mm CL) similar to the one reported by (Paramo & Saint-Paul. (2012) (30.05 mm CL); this finding indicates that FSH is related to size at the beginning of sexual maturity. Therefore, the size of the abdomen is a good indicator of the beginning of morphological sexual maturity since it has a relation with t of eggs.

Females and males showed a positive allometric growth rate similar to that found for this species in Venezuelan waters (Gómez et al. 2005). As a consequence, the Caribbean lobster reveals changes associated with the intrinsic growth rate, obtaining a greater gain in biomass in relation to size (Serrano-Guzmán 2003). Morphometric relationships, besides providing information on growth variation, may also help to predict size at the beginning of maturity and spawning period taking into account changes in the shape and size of the abdomen and pleopods during egg maturation (Josileen 2011, Severino-Rodrigues etal. 2016). Therefore, further research is necessary on whether morphometric indices are affected or not affected by the particular stage of maturity of the female (Queiros et al. 2013). Paramo & Saint-Paul. (2012) provided evidence of diel patterns for M. binghami that revealed a nocturnal behaviour most likely for feeding and a burying behaviour during daylight, as the largest catches were taken during nocturnal trawls. Consequently, more research is required on seasonal patterns in emergence and sex ratios of M. binghami in the Colombian Caribbean. Knowledge of the dimensions of different parts of the body may be useful for studies on the life history of M. binghami. The morphometric relationships presented in this work can be very useful for population studies of the same species in different geographic locations. The size structure, size at sexual maturity, growth type and morphometric relationships are important parameters of the life history, as well as of great utility for the management of a new deep-sea fishery in the Colombian Caribbean. This kind of information is very useful for the organizations in charge of establishing fishing management strategies in populations that are still considered unexploited. In this way, management strategies such as closures and fishing gear controls can be implemented thus avoiding resource depletion (Marasco et al 2007).

Conclusions

According to the results found, M. binghami is a potential alternative resource for the Western Atlantic fishery (Cobb & Phillips 1980); however, prior to the beginning of a new fishery, more biological research is needed to understand the life cycle parameters of the species such as growth, spawning, recruitment, mortality, spawning areas, nursery areas and associated biodiversity. This information will help in the development of appropriate strategies to initiate and sustain a new commercial fishery in the Colombian Caribbean taking into account the protection and conservation of the ecosystem and contributing to food security.