What you are reading is a translation. It began as an oral presentation with slides, and now I have written it down.

No, that is not right. It began much earlier. I based my presentation on an opaque theoretical article I wrote for the International Journal of Communication (Conway, 2017). Moreover, that article reworked Stuart Hall’s (1973, 1980b) encoding/decoding model to see what it had to reveal about translation (for that matter, so does what you are reading). Hall’s model, in turn, reworked Marx’s (1993 [1857]) take on political economy in the Grundrisse (and the Grundrisse reworked older versions of political economy, which themselves reworked... which reworked… which reworked...)

In other words, there is no point of origin. What you are reading is the result of one long series of transformations and substitutions: encoding/decoding substitutes for the Grundrisse; my article substitutes for encoding/decoding; my talk substitutes for my article; and now, what you are reading substitutes for my talk. It is a translation. It could not be otherwise.

That I should describe it as a translation is no coincidence. My purpose in this essay is to ask what would happen if cultural studies scholars talked about translation. Or, more to the point, what would a theory of translation look like if it were grounded in the field of cultural studies? The answer I give is as performative as it is expository. That is, the logic that shapes my answer also applies to the essay itself, and it shapes its form. My essay-like every other form of discourse-participates in an economy of substitution that I call ‘translation’. In that respect, my opening examples are strategic: they show how translation works before I even say what I think it is. The examples I choose in the sections that follow are also strategic: they illustrate a key relationship between signs by moving between semiotic systems (for example, between words and pictures or between linguistic registers).

So what, then, is that relationship? What exactly is translation? To answer that question, I propose three axioms:

To use a sign is to transform it

To transform a sign is to translate it

Communication is translation

In the following sections I work through these axioms, after showing where cultural studies and translation studies have failed to connect despite their shared interests. I take as my starting point one of the seminal essays in cultural studies; it is, of course, Stuart Hall’s (1973, 1980b) “Encoding/Decoding”. It serves as the basis for a materialist approach to semiotics, which provides the conceptual tools to pry open the act of speaking and responding to see how signs transform when we use them. Taking my cues from Hall, whose essay has had a profound impact on scholarly notions of politics, I offer a related conjecture: The transformation and substitution of signs opens up a space for a politics of invention, where we can rethink our relation to cultural others so that people we once feared can find their place in the communities we claim as our own.

Disciplining the Fields

First, a more basic question: what constitutes the fields of cultural studies and translation studies?

My formal training is in cultural studies, but my principal object of study has long been translation, and I often publish in translation studies journals. I have observed, as have others, that there is little exchange between these fields: “to a large extent, media, cultural and globalization studies have essentially ignored questions of language and translation” (Demont-Heinrich, 2011, p. 402). Even when cultural studies and translation scholars examine the same things, they often talk past each other. Translation scholars, for instance, have catalogued the many ways translators are influenced by the ideologically charged sociocultural contexts within which they work, nuances that many cultural studies scholars fail to see. Translation scholars, on the other hand, often overlook the complex and contradictory forms of influence that texts have over audiences, forms that cultural studies scholars have deftly explored.

For that reason, I intend this essay as an opening point for a new line of inquiry, one that puts cultural studies and translation scholars into conversation. However, it is important not to treat these two fields (or their objects of study) as existing a priori. These fields are contested, and they cohere only by virtue of the disciplining habits of their members. That is, they are relatively closed systems: what makes people cultural studies scholars is that they attend cultural studies conferences and publish in cultural studies journals. What marks those conferences or journals as belonging to cultural studies is that cultural studies scholars go or publish there. It is the same case for translation studies. These venues foster conversations among likeminded scholars, who share specific preoccupations that motivate them to examine similar objects. Over time, these fields have developed differently in response to their respective preoccupations, and they bring different lenses to bear on their objects of study (see Hall, 1980a; Bassnett, 1998; Conway, 2013).

Still, there is nothing inherent in either field that would prevent scholars from crossing over. Their closure is only relative, not absolute. There are certainly translation scholars, such as Susan Bassnett whose work is shaped by cultural studies (see, for example, Bielsa & Bassnett, 2009). If we use departmental affiliation as an index of disciplinary affiliation, we also find a handful of cultural studies scholars interested in translation (e.g, Moran, 2009; Rohn, 2011; Guldin, 2012; Uribe-Jongbloed & Espinosa-Medina, 2014). But these scholars are the exception that proves the rule: the paucity of exchange suggests that artificially maintained boundaries remain. If this essay serves to encourage conversation, it will do so by revealing the points where each field’s grindstones help sharpen the other field’s tools.

Theoretical Foundations: A Materialist Approach to Semiotics

The axioms I propose have two starting points: materialism and semiotics. The materialism comes, as mentioned in the introduction, from Stuart Hall’s essay “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse” (Hall, 1973), better known in its revised form, “Encoding/Decoding” (Hall, 1980b). It was Hall’s reaction to behaviorist models of mass communication, which treated television as a stimulus for which we could measure various responses. Hall argued instead that television programs were only one moment in a circuit that linked producers and viewers in a specific social context.

The encoding/decoding model, in fact, is an application of Marx’s political economy, as laid out in his introduction to the Grundrisse (Marx, 1993 [1857]). Marx’s insight was that production and consumption were not independent moments in the circulation of commodities but were, on the contrary, mutually constitutive-one could not exist without the other. On the one hand, to give an example, the objects a cobbler produces become a pair of shoes in a meaningful sense only when someone puts them on his or her feet. In this way, the act of consumption is implicated in the act of production. On the other, the cobbler produces shoes in such a way as to influence how people wear them, by altering materials and styles to create a demand. In this way, production is implicated in the act of consumption.

Hall extends this analysis to television. He describes the moments of production and consumption-“encoding” and “decoding”-as mutually constitutive. Producers encode certain meanings into shows, but viewers do not necessary decode them as intended. Instead, producers and viewers both operate within their own respective frameworks of knowledge, shaped by the structures of production and the technical infrastructure at their disposal. The moments of production and consumption are linked in that producers anticipate viewers’ reactions, and viewers interpret shows in part based on their knowledge of producers. Thus the shows themselves are complex signs that link producers and viewers, who also operate within a shared social context.

In short, production and consumption are linked in a relationship of mutual dependence. Hall frames these forms of mutual influence as a circuit, which he illustrates in Figure 1 below:

I have adapted the figure Hall presents in the earlier version of his essay, which differs from its better known counterpart (Hall 1980b) in one important way: it has an arrow that runs from the factors that influence decoding to those that influence encoding. In other words, it completes the circuit by making the influence of decoding on encoding explicit.

What makes Hall’s model materialist is that the factors that influence encoding and decoding-people’s frameworks of knowledge, the structures of production, the technical infrastructure-all relate to the material conditions of textual production and meaning-making. But the psychological aspects of meaning-how programs evoke ideas for viewers-remain unclear. Hence my second starting point, the idea of a sign. Here I draw on American philosopher Charles Peirce (1940), who says,

A sign [...] is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. (p. 99)

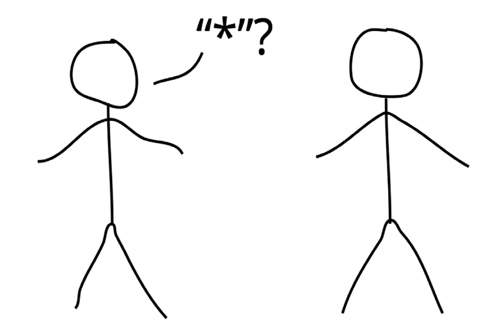

Consider my stick-figure heroes in Figure 2. The star spoken by Hero 1 (on the left) is the sign because it evokes something for Hero 2 (on the right). And the ideas it evokes for Hero 2 are also signs, as they evoke still more ideas, which evoke more, and more, and more (my image cannot capture the full chain of associations). This is what Peirce (1940) means when he speaks of the interpretant1

It is useful to make a distinction here between the material and subjective aspects of the sign. On the one hand, there is the material side-the specific patterns of vibrating sound that hit our eardrums in the case of a word, for instance, or the patterns of light and sound in the case of a television program, or Hero 1’s star. On the other, there is the subjective side-what a speaker or producer hopes to evoke by using a given material sign (a word, a TV program, etc.), and what that material sign evokes for a listener or viewer, as in the case of Hero 2’s chain of associations. The subjective aspect of the sign consists in the string of interpretants evoked by the material sign.

Axiom 1: To Use a Sign is to Transform it

How does a materialist approach drawn from Marx’s political economy and 1970s-era reactions to behaviorism relate to the idea of a sign made up of material and subjective parts? As Hall (1980b) demonstrates, the televisual sign links producers and viewers. Its meaning is a point of negotiation between them, which is shaped by their knowledge and expectations of each other. But this negotiation over meaning is not unique to television. In Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, Vološinov (1986 [1929]) argues that we negotiate the meaning of every sign. He gives the example of a word:

[A] word presents itself not as an item of vocabulary but as a word that has been used in a wide variety of utterances by co-speaker A, co-speaker B, co-speaker C and so on, and has been variously used in the speaker’s own utterances. (p. 70).

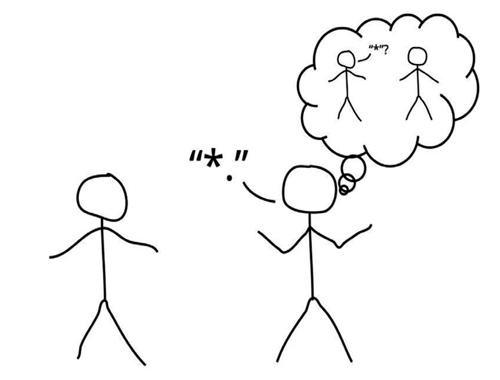

When Hero 1 on the left uses a sign (Figure 3)...

...Hero 2 on the right responds by taking into account how Hero 1 used it (Figure 4). If Hero 2 uses it again, it is with the earlier exchange in mind, at least partially.

But we are more than just reactive: when we talk to people, we are also predictive. As Mikhail Bakhtin (1986) points out:

When constructing my utterance, I try actively to determine this response. Moreover, I try to act in accordance with the response I anticipate, so this anticipated response, in turn, exerts an active influence on my utterance (I parry objections that I foresee, I make all kinds of provisos, and so forth). (p. 95)

In other words, just as TV producers shape their programs in partial anticipation of what viewers will think (Hall, 1980b), we shape our utterances (whatever form they might take) in partial anticipation of how others will react (and we do so in a given social context, to return to Hall’s model).

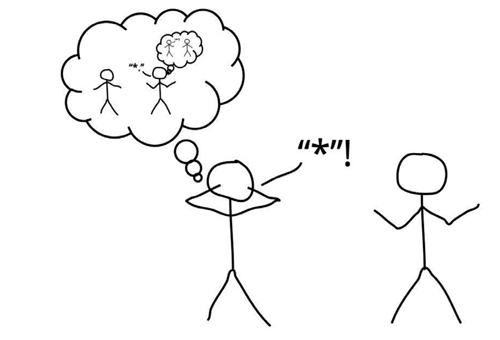

Thus, our heroes continue to pass a word back and forth, each time reacting to what the other has said and taking that reaction into account. Perhaps they have a discussion. Perhaps Hero 2 is really a jerk, or maybe just clumsy with Hero 1’s feelings. Maybe Hero 2 is not really a hero at all (Figure 5):

So Hero 1 leaves, while Hero 2 calls after Hero 1 in vain (Figure 6):

Finally, Hero 2 is left to replay the scene, to figure out what went wrong. The sign means something for Hero 2 that it did not mean before. At the beginning of the conversation, it did not evoke regret or puzzlement, and now it does (Figure 7).

This is what I mean when I say “to use a sign is to transform it.” The material aspect of a sign may remain the same over the course of an exchange, but the subjective aspect does not. And if the material aspect is one side of a sign, and the subjective aspect the other, then the pair has changed. The sign-the pair together, as a unit-is different from what it was before.

Axiom 2: To Transform a Sign is to Translate it

Hence my second axiom: to transform a sign is to translate it.

Perhaps this axiom appears counter-intuitive or based on a notion of “translation” that I have had to wrangle and contort. In fact, the opposite is true. What do I mean by “translation”? Exactly what it means in a conventional sense-the substitution of one sign (or one set of signs) for another. In the typical case, this substitution is made based on ideas of equivalence, or something approaching it. The idea of equivalence is contested in translation studies (no language maps neatly onto another), but it is a useful and necessary fiction. We cannot substitute words willy-nilly, debates about equivalence notwithstanding, because if we did, we would no longer be giving readers an idea of what a text in a foreign language says. Hence, when Walter Benjamin 1997 [1923], in his famous essay on the translator’s task, quotes Stéphane Mallarmé, who speaks of “Les langues imparfaites en cela que plusieurs,” there are many different ways we could render his phrase in English, but they will all have to mention something like “Languages, imperfect due to sheer number” (Figure 8).

This definition of translation remains relevant here. We transform signs by using them: their subjective dimension changes because Hero 2 has to take into account the use by Hero 1, something Hero 1 did not have to do. Thus, the transformed sign substitutes for the sign that came before. The change might be small (in fact, most of the time it is), but we can also imagine more dramatic cases, such as when Hero 1 tells Hero 2 something life-changing, and Hero 2 must make sense of a new configuration of his or her semiotic universe (think of Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back-the sign “father” changes dramatically when he learns who Darth Vader really is.)

Or think of how the sign “translation” has changed for you since the beginning of this essay. As you think of questions you want to ask and points you want me to clarify, you are taking into account what I have said. The chain of associations-that is, the interpretants-the sign “translation” evokes for you has grown. Perhaps not dramatically, but it is larger nonetheless. The subjective aspect of the sign has changed, which means the material/subjective pair as a unit has changed. I have substituted one use of the term for an older use. At the risk of being too clever, I would say I have translated “translation.”

Axiom 3: Communication is Translation

Here we arrive at my third axiom: “Communication is translation.” In all truth, the first two axioms form a syllogism, from which the third one derives. If we use a sign, we transform it. If we transform a sign, we translate it. Therefore, if we use a sign-that is, if we communicate-we translate it. In other words (what a revealing phrase-“in other words”), communication is translation.

In some ways, this assertion is not new. George Steiner, in his influential book After Babel 1998 [1975], argued,

Any model of communication is at the same time a model of translation, of a vertical or horizontal transfer of significance. No two historical epochs, no two social classes, no two localities use words and syntax to signify the same things, to send identical signals of valuation and inference. Neither do two human beings. (p. 47)

Paul Ricoeur, in his book On Translation (2006), goes further. Because the sign I use never evokes the exact same thing for you as for me, we constantly misunderstand each other. We say what we have to say, but then we also have to explain what we mean. Sometimes we have to explain our explanation, until we are as satisfied as we can be that we have gotten our message through:

[I]t is always possible to say the same thing in another way. [...] That is why we have never ceased making ourselves clear, making ourselves clear with words and sentences, making ourselves clear to others who do not see things from the same angle as we do. (pp. 25-27)

Language is reflexive, and tant mieux-if we could not talk about what we mean, especially when we see our point has not gotten through, communication would grind to a halt.

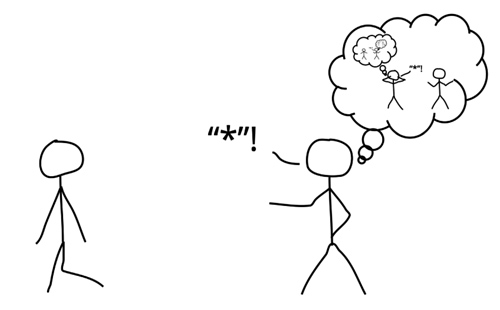

Note, however, that Steiner 1998 [1975] and Ricoeur (2006) make an assumption that I do not. They presume there is an active agent, someone thinking about the meaning of signs, in that they are explaining, “When I said X, what I really meant was...” In effect, they are translating X by “say[ing] the same thing in another way.” But if each use of a sign transforms it, then there is no need for an active agent. Transformation and translation take place whether we think about what signs mean or not. Hero 1 says “*” and Hero 2 adds that use to his series of interpretants, so when Hero 2 says “*” it is not an identical sign (Figure 9).

Conjecture: A politics of Invention

Why dwell on this seemingly minor point? Because as Stuart Hall showed with television, the gap between the producer’s intended meaning and the meaning a show evokes for a viewer is the condition of possibility for acts of resistance. Because we are intelligent human beings, and because we have our own experience that differs from that of the people who produce television, we do not have to agree with what we see on TV. In fact, we can take what we see and arrive at radically different-and equally plausible-interpretations, as we reconfigure meanings to match with our experience and meet our expectations.

That idea of resistance leads me to my conjecture: the gap between signs is productive, something we can put to use. We must (as the London Underground reminds us) mind the gap. I have begun to investigate this conjecture as both a theoretical and an empirical question. In particular, I am interested in how we use language to invent ways to welcome strangers into our midst. How do Canadians, for instance, persuade their compatriots to vote for a party whose leader, Justin Trudeau, wants to welcome Syrian refugees? How do politicians frame “refugees” in order to persuade voters not only that welcoming refugees is the right thing to do but also that voting for them is the right way to do it? (An interesting question to pose, given the contrast with the political scene in Canada’s neighbor to the south-and my home country-the United States.)

Such questions are at the heart of what rhetoricians, drawing on Aristotle, describe as invention. In On Rhetoric, Aristotle says that rhetoric is the art of persuasion, and invention-one of the five canons of rhetoric-is the ability to “see the available means of persuasion in each case” (Aristotle, 2007, p. 36). Invention in this sense is contingent on circumstances, which change from one situation to the next. It is grounded in the moment of speaking and therefore not knowable in advance. It is a matter of thinking on your toes.

My contention-my conjecture-is that the gap between a speaker’s sign and a listener’s sign is a space where we can practice a specific type of invention concerned with hospitality. This gap allows us to speak against the hegemonic norms of identity that prevent people who appear different or foreign from joining “our” group, whichever it is. It is a matter of identifying the “available means of persuasion.” This act is a fundamentally creative-and fundamentally ethical-act.

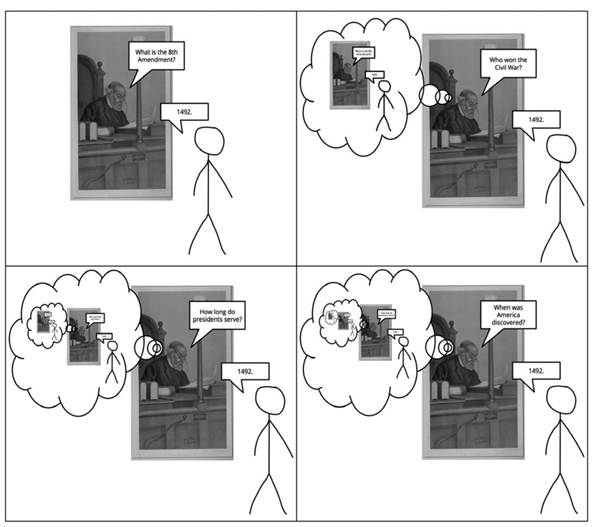

Let me illustrate with an example, which comes from Bertolt Brecht, by way of translation studies scholars Boris Buden and Stefan Nowotny (2009). In his poem “The Democratic Judge,” Brecht describes an Italian immigrant to the United States who is applying for citizenship, but he does not speak English. The man stands before the judge, and the judge asks him questions about the United States, as part of a citizenship test. “What is the eighth amendment?” the judge asks. “1492,” he answers because he does not understand.

The setting of the exchange is symbolically important. The applicant is asking for admission into a new national community. It is the culmination of a long process of asking-from immigration, to integration (in different senses, as he does not speak English), to finally making a formal request. Thus, when he is refused, according to Buden and Nowotny, it is a literal refusal of his symbolic request, one more refusal on top of all the others he has faced since arriving in his new home.

So the man returns later, and the judge asks another question. “Who was the winning general of the Civil War?”

Again the man answers, “1492.”

Again, he is refused.

He returns a third time, and the scene repeats itself:

“How long do presidents serve?”

“1492.”

But something happens for the judge. It is a moment of invention. When the man returns a fourth time, according to Brecht:

The judge, who liked the man, realised that he could not learn the new language, asked him how he earned his living and was told: by hard work.

And so at his fourth appearance the judge gave him the question: When was America discovered?

And on the strength of his correctly answering 1492, he was granted his citizenship. (as cited in Buden & Nowotny, 2009, pp. 206-207)

The judge looks at the situation and assesses it. He looks at the tools available to him. He is a judge, so he cannot break the law, but he takes pity on the man and decides the United States would be better for having him as a citizen. Given those constraints, he contrives a question-one that is in line with all those he has already asked, although today it would be a bit anachronistic-that the man can answer. The judge has worked within the constraints imposed on him to make a stranger no longer strange, a new member of the national community.

Buden and Nowotny (2009) say that the judge has found “a correct question” for “a wrong answer” (p. 207). The judge has taken advantage of the gap between one use of the sign “1492” and the next. Over the course of his interactions with the man, the sign “1492” has come to have a richer set of interpretants. In each case, but especially in the question that sets up the final, “correct” use, he has taken his previous interactions with the man into account. Hence the expanded set of associations. What is important is that the judge finds a way to make the evolution of the sign’s meaning productive-it becomes a tool in an ethical act of inclusion (Figure 10).

Source: Modified from “Men of the Day No.756: Caricature of Mr. Franklin Lushington (1823-1901)”, in Vanity Fair (Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 10 Brecht’s judge devises the correct question for a wrong answer

It is not hard to think of other situations where such invention has value, or where scholars can use this idea to gain insight into our interactions with groups who are marked as “different” or “foreign.” How do politicians in Canada and the United States, to return to the questions I posed above, use words like “refugee” in such a way as to persuade voters to accept people fleeing war? How do they encourage voters to associate ideas such as opportunity or hospitality with the word “refugee”? What role do signs play in the symbolic universe through which politicians and voters navigate, and how can they find ways to understand these newcomers so that they no longer remain others?

Conclusion

In the introduction, I wrote that what you are reading is a translation, a reworking of another article. Why have I made the same argument twice? What is the value of the repetition? What does this version offer that the older version (or past links in the chain) did not?

One answer to these questions is relatively superficial. The first version (Conway, 2017) relied on a deductive mode of reasoning. It was a series of literal and implied “if-then” statements. I crafted the version you have just read to rely more on induction-I proceed by examples and build to my conclusions from there. I hope this version achieves a different effect-I hope it left blanks that you filled in. In short, I wanted it to demonstrate invention as much as explain it.

Another answer to these questions goes still further. In the introduction I also asked: What would a theory of translation look like if it were grounded in the field of cultural studies? The answer I give is as performative as it is expository. That is, the logic that shapes my answer also applies to the essay itself, and it shapes its form.

How does this logic apply? This question and these statements are signs, by Peirce’s (1940) definition, in that they “[stand] to somebody for something in some respect or capacity” (p. 99). Their use here differs from their use in my introduction, if I have succeeded in my translation, because they evoke something new for you. The first time, I had hinted at but not laid out the logic of transformation-substitution. You had to take my assertion on faith. Now, I hope, it stands on its own merits.

The questions of invention that follow from this conception of translation are ones I think we should be asking in the field of cultural studies. If we develop a theory of translation that responds to our concerns, and if we bring the tools we have developed to bear on such a theory, we can conceive new approaches to politics and ethics. In a world where the forces of globalization are constantly accelerating, and where we come into greater and greater contact with people unlike ourselves, few tasks could be as important as this one.