Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria

versão impressa ISSN 0122-8706versão On-line ISSN 2500-5308

Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecuaria vol.20 no.2 Mosquera maio/ago. 2019

https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol20num2art:1463

Economía y desarrollo rural

Review of the measurement of dynamic capacities: a proposal of indicators for the sheep in

1Profesora visitante, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales. Madrid, España.

2Profesora titular, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales. Madrid, España.

3Profesor titular, Universidad de Córdoba, Departamento Producción Animal. Córdoba, España

4Profesor colaborador, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales. Madrid, España.

5Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria - Corpoica

The sheep industry is one of the leading sectors in the Castilla-La Mancha economy in Spain. It occupied the fourth position in the European context in 2017. The income of this sector stems mainly from the sale of milk and derived products with pdo (protected designation of origin) as the “Manchego cheese” that generated 61.21 % of the economic value of the pdo products in Spain during 2016. However, nowadays these farms need to develop management skills to improve their competitiveness as they suffer from lack of adequate managerial performance. These circumstances joined to the fall in the prices of milk used for pdo and the increase in the cost of animal feed is generating viability problems. Considering the above, the aim of this research consisted in identifying a group of indexes that allow measuring dynamic capabilities in the sheep industry. From the methodological perspective, a revision of the academic literature in dynamic capabilities was carried out, and specific potential indicators for the sheep management industry have been identified to measure these capabilities. As a result, 54 indicators have been identified and justified to measure different kinds of capabilities. To conclude, it should be noted that these indicators constitute a standard for managers to measure, diagnose and make decisions focused towards improving farm management.

Keywords dairy farms; innovation; management; milk products; sheep

El sector ovino es uno de los principales sectores que impulsan la economía en Castilla-La Mancha. Así, en 2016 la denominación de origen protegida (dop) “queso manchego” generó el 61,21 % del valor económico de los productos con denominación de origen en toda España. Sin embargo, actualmente las explotaciones adolecen de un adecuado desempeño gerencial que, unido a la caída en el precio de la leche destinada a la dop y el aumento en el coste de alimentación del ganado, está generando problemas de viabilidad. Teniendo en cuenta esta problemática, el objetivo de este trabajo consiste en identificar un conjunto de indicadores que permitan medir capacidades dinámicas en el sector ovino. Desde la perspectiva metodológica, se ha realizado una revisión de la literatura en capacidades dinámicas y se han determinado potenciales indicadores propios de la gestión ovina que permitan medir dichas capacidades. Como resultado, se han identificado y justificado 54 indicadores para medir los distintos tipos de capacidades. A modo de conclusión, estos indicadores constituyen un referente para que los gerentes puedan medir, diagnosticar y tomar decisiones de mejora en la gestión de sus granjas.

Palabras clave gestión; granjas lecheras; innovación; ovinos; productos lácteos

Introduction

The sheep sector is a strategic sector in Spain, and in particular in Castilla-La Mancha, where the Manchega sheep plays a fundamental role since it contributes to the sustainability of the population and the development of these rural areas (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación [Mapama], 2015). More specifically, the dairy sector in which this revision work is centered is continuously evolving; from January 2010 to January 2018, there has been a decrease of 19.99 % in reproduction farms for milk production and mixed breeding throughout Spain. Furthermore, the number of sheep heads in Castilla-La Mancha has also been reduced by 29.9 % between November 2009 and November 2017 (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación [Mapama], 2018). According to the data provided by this same source, the price of milk with protected designation of origin (pdo) in this region has fallen by 5.29 % between 2016 and 2017, while the mean cost of a full animal ration in Spain has increased by 4.49 % between the months of December of those same years.

Despite this adverse situation, the production of sheep milk in Castilla-La Mancha (in thousands of liters) in 2016 increased by 15 % compared to the previous year (2015), and milk deliveries increased by 5.07 %, being the second Autonomous Community that carries out most of the deliveries in Castilla y León. The liters of sheep milk declared as a direct sale by the producers in Castilla-La Mancha have increased by 14.13 % between 2016 and 2017: “The agricultural, livestock, forestry and fishing activities contributed 6.63 % to the regional GDP in 2015. In the period from 2008 to 2015 these activities have grown economically and in productivity. Further, these are specific activities with national representativeness” (Castilla La-Mancha [clm], 2018, page 23); this same source considers pdo products as a strength for the internationalization of products and services of Castilla-La Mancha.

The response of producers to this crisis has been very different. The changes have been aimed at increasing production, skilled labor, the use of technologies, and the progressive reduction of grazing (Angón et al., 2015). These structural changes imply a risk in the viability of livestock farms since they generate an impact on their multifunctional nature and reduce the degree of complementarity existing between different activities (Ryschawy, Choisis, Choisis, Joannon, & Gibon, 2012, 2013). Hence, the implementation of process management programs (pmp) in reproduction and genetic improvement has become one of the main actions of this industry (Milan, Caja, González-González, Fernández-Pérez, & Such, 2011). In agreement with the results obtained by Morantes et al. (2017) in a study on management performance in production systems with sheep in Castilla-La Mancha, in these farms, there is a low management performance. In recent years, several studies have been conducted in this sector from different points of view. Thus, the impact of different technological packages (Rivas, Perea et al., 2015) and the influence of managerial performance (Morantes et al., 2017) have been analyzed.

According to the theory of dynamic capabilities (Teece & Pisano, 1994; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997), the deployment of these capabilities allows the development of a sustainable competitive advantage. Therefore, the aim of this work is to conduct a review of the literature on the measurement of these capabilities to identify indicators specific for sheep farms. The measurement of these capabilities will allow obtaining knowledge on the situation of each operation compared with the average and with the best practices.

Materials and methods

From the methodological perspective, a review of the literature aimed at identifying dynamic capabilities and indicators that measure these in the sheep sector has been carried out. The bibliographic sources reviewed include articles and books located in the databases abi, Scopus, Econlit and Web of Science from the period between years 2001 and 2017.

Besides, a review of the variables used by producers and managers of sheep farms in Castilla-La Mancha was carried out to establish an analogy with the information obtained during the assessment. These variables were justified by the review and are considered as indicators of different types of capabilities. For the analysis of the variables, the database generated between June and September 2012 was used (Rivas, Perea, et al., 2015).

Results and discussion

Dynamic capabilities

Teece et al. (1997) defined dynamic capabilities as follows:

The ability of an organization to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address exceedingly changing environments. A capability to be strategic, it must cover a customer need (so there is a source of income), it must be unique (so the products/services produced can be assigned a price without considering too much the competition), and difficult to replicate (so the benefits will not have competition). The key feature of a distinctive competence is that there is no market for it, except, possibly, through the business unit market. Therefore, competencies and capabilities are attractive assets that must be built because they cannot be bought (p. 516-518).

Since this term emerged, different authors have conducted research that provides new points of view. Currently, there is a consensus regarding the definition of dynamic capabilities. However, there is no consensus among different researchers concerning the types of dynamic capabilities (Monferrer, Blesa, & Ripollés, 2013) and the indicators to measure these (Wang & Ahmed, 2007).

Therefore, in this research work, the types of dynamic capabilities established by De-Pablos and López Berzosa (2012) have been adopted:

Detection capability. Ability to detect the environment and understand the customer's needs better than the competitors (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993).

Absorption capability. Ability to recognize the value of something new, assimilate the information and apply it for commercial purposes (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

Integration capability. Ability to integrate diverse patterns of interaction through contribution, representation, and interrelation (Okhuysen & Eisenhardt, 2002).

Innovation capability. Ability to develop new products and markets, through coordination of strategic and novel orientations with innovative behaviors and processes (Deeds, DeCarolis, & Coombs, 1999; Delmas, 1999; Lazonick & Prencipe, 2005; Petroni, 1998; Tripsas, 1997; Wang & Ahmed, 2004) (p. 23).

Measurement of detection capability

Access to adequate information is fundamental for organizations as it allows them to be in a better position to achieve a competitive advantage (Collins & Clark, 2003), by obtaining better results when identifying changes in the market and being able to respond adequately to these; hence, external social relationships of managers directly influence the detection capability (Nieves, 2014).

In this sense, the ownership of the pdo “queso manchego”, as well as the incorporation of unifeed feeding systems or by-products as feed for animals that allow optimizing the diets, are considered indicators of the detection capacity given that they access timely and adequate information to achieve the strategic objectives of livestock farms.

Guerras-Martín and Navas-López (2015) point out that products of companies can be described by the needs of the clients they cover and by the technology they employ, while the markets are described by the needs they satisfy and by their target customers. Therefore, the commercialization of products such as lambs, rams, live females, live males, cheese, wool, manure or different varieties of cheese implies that a niche of customers that demanded these products has previously been detected. The same applies to direct purchase to the consumer or the wholesaler, since an opportunity has been detected through the expansion of the clients to whom it is directed and, therefore, of its field of activity.

A similar situation is what happens with agricultural products; the diet has changed, and the weight of products from agriculture has increased due to changes in the culture of society (Alfonso et al., 2001, Cussó, 2005), so those farms that have a surface for agricultural use and employ it for food production are responding to a need detected in society. In previous cases, the ability to understand the environment and the needs of customers has been developed (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993).

Rubino, Pizzillo, and Masoero (2010) relate the intrinsic quality and nutritional content of milk and cheese with the type of management and establish that it is higher in the case of grazing animals without supplements compared to stabling animals with supplements.

Although the operations assessed in this work do not have modern information systems such as Big Data that allow these to conceive new businesses according to customer needs (De-Pablos, López-Hermoso, Martín-Romo, & Medina 2013), the availability of records provides them with sufficient information regarding which products have a higher demand and how their demand evolves. This allows them to analyze the information and detect niches of customers whose needs have not been met.

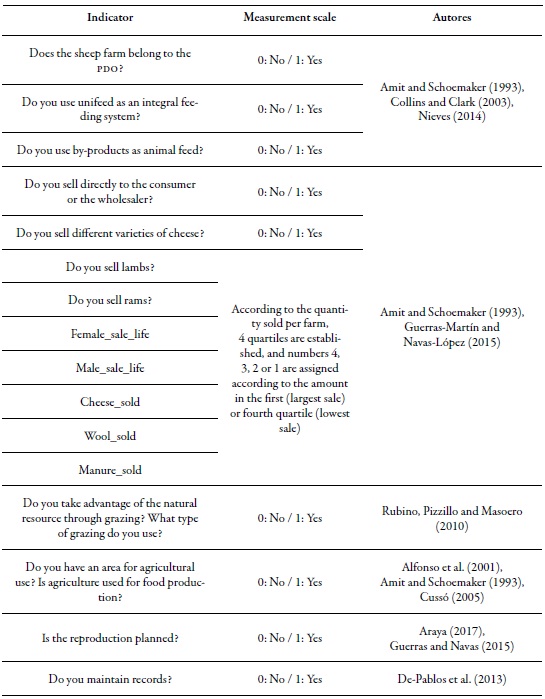

Through planning, organizations seek to adequately use their resources to meet the needs of customers (Guerras-Martín & Navas-López, 2015). Carrying out reproduction planning involves an analysis of the market and, in this way, establish how many animals will be needed to satisfy the demand or what quality features the animals must meet so that the customers value the final product. Thus, the planning of the reproduction would facilitate the adaptation of the operation to the future needs of the customers. The planning of any organizational process is based on the initial detection of needs, in order to achieve the strategic objectives of the organization (Araya-Leandro, 2017). Table 1 shows the detection capability indicators proposed and the authors that support these.

Measurement of absorption capability

The measurement of absorption capability has largely been studied. Several authors such as Aragón and Rubio (2005), Minbaeva, Pedersen, Bjorkman, Frey and Park (2003) and Murovec and Prodan (2009) conclude in their research that the level of absorption capability improves with human resources management practices, e.g., training.

Likewise, the studies carried out by Rasli, Madjid and Asmi (2004, cited by González and García-Muiña, 2011) and Aragón and Rubio (2005) show that recruitment and selection processes are decisive in the absorption capability of organizations.

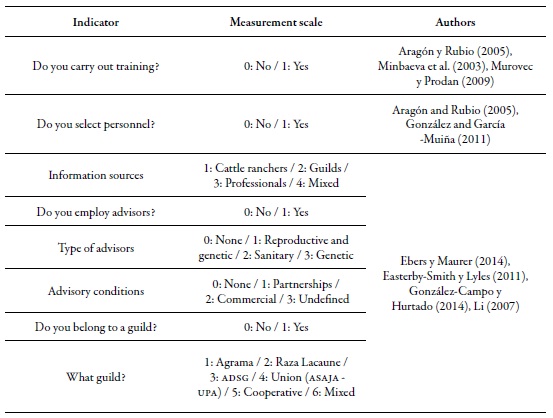

Authors such as Li (2007), Easterby-Smith and Lyles (2011), Ebers and Maurer (2014) and González-Campo and Hurtado (2014) emphasize that access to external information sources is directly related to the absorption capability, as it allows organizations to gain access to valuable external knowledge. Therefore, access to external information sources (e.g., livestock farmers, guilds, professionals) and the use of advisors on essential aspects of their activity, the conditions of such advisory services and the frequency of these, are indicators of absorption capability in livestock farms. Table 2 shows the indicators of absorption capability proposed and the authors that support these.

Measurement of integration capability

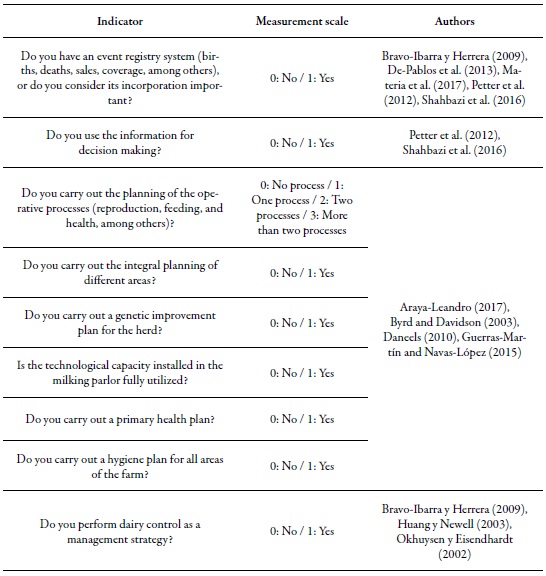

As De-Pablos et al. (2013) stated: "knowledge is the information set in the context of an experience, which can be personal or collective" (p 43). Bravo-Ibarra and Herrera (2009) considered that knowledge management and organizational routines establish the company's integration capability and point out that good practice is the use of technology to transfer knowledge. Currently, information technology systems provide mechanisms for strategic management decisions (Petter, Delone, & McLean, 2012; Shahbazi, Haghshenas, Nassiriyar, & Sadeghzadeh, 2016) and to integrate external knowledge into the activities of organizations (Materia, Pascucci, & Dries, 2017).

Consequently, an event registration system in livestock farms can be considered as a database that stores relevant information in the operating process of these types of operations. This database allows the use and exchange of information through employees (Bravo-Ibarra & Herrera, 2009) and, subsequently, it can be used for decision making; this information becomes part of the operation, not of the individual, and can lead to changes in existing organizational routines or the design of new ones. The use of this information increases its efficiency, which gives rise to a better understanding of what would be provided by each of the activities of the livestock operation value chain separately.

The planning process refers to the definition of the company's objectives and the most appropriate means to achieve them (Araya-Leandro, 2017; Guerras-Martín & Navas-López, 2015); that is, it includes making decisions in the present about the future of the company, which translates into an organizational capability of the company (Byrd & Davidson, 2003). Managers need to know the existing resources in the company, a situation that impacts on the development of dynamic capabilities (Daneels, 2010), and must also understand the organization as a whole, as well as its relationship with the environment (Guerras-Martín & Navas-López, 2015), which facilitates the coordination of employees and the development of behavior patterns.

In this sense, the use of the technological capacity installed in the milking room supposes a global vision of the operation, given that information about the number of sheep in the farm that provides milk, the periodicity with which they must be milked, and the available technological capacity must be known.

For this reason, and in this research, it is interesting to use the variables referring to the planning, plans, and use of the technological capacity installed in the milking room as indicators of the integration capability.

The use of milk control as a management strategy allows livestock farms to differentiate their livestock by production and allows them to select those sheep that best fit the characteristics that milk must meet to make Manchego cheese. Also, this strategy facilitates their comparison with other farms to know in what situation they are. To the extent that the farms use this management strategy, they will integrate the knowledge acquired about their position compared to other farms and the features of their dairy production with the internal knowledge they already have, and adapt their organizational routines as a result of this integration, through simple formal interventions, which will make decision-making easier for decision-makers (Bravo-Ibarra & Herrera, 2009; Okhuysen & Eisendhadt, 2002).

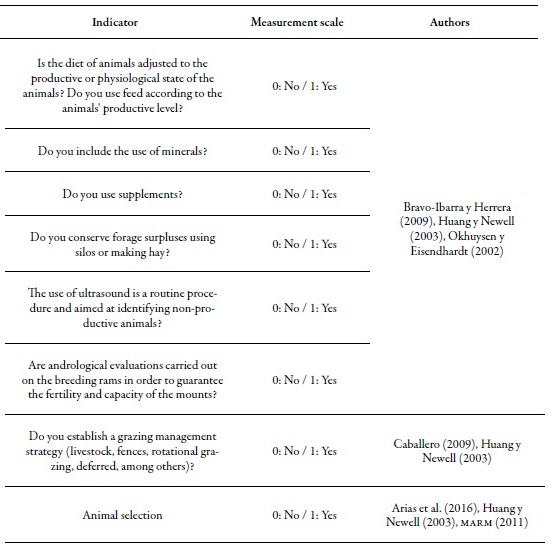

In this sense, the adaptation of the diet to the productive state of the animals, the use of minerals and food supplements, or the use of food conservation methods such as silage or haymaking to provide quality feed to livestock at times when there is no fresh food available, favor that the cattle operations reach efficiency in their productive processes.

The use of ultrasound scans to identify nonproductive animals as well as the andrological evaluation of the rams involves the integration of that knowledge with the one that the operation itself already has, allowing the management to make decisions about how to use these non-productive animals efficiently. Likewise, the use of management strategies such as livestock, fences, rotational or deferred grazing, among others, integrates ecological knowledge in the improvement of sustainable pasture management (Caballero, 2009).

With regard to the selection of animals, since 1988 a program to improve the Manchega breed is in force aiming at "increasing milk production per sheep and lactation, which will establish an increase in economic profitability and sustainability of the exploitations" (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural Marino [marm], 2011, p.7). Thanks to this program, a significant increase in milk production has been obtained (Arias et al., 2016). In this way, the selection of the most suitable animals for dairy production allows the farms to be more efficient.

In all the indicated cases, it can be affirmed that these methods, techniques, and strategies are the result of the knowledge integration capability into new knowledge because it has been developed within the operation or acquired through relationships with other breeders or associations and with the existing knowledge within the operations. Further, this facilitates this knowledge becoming explicit through organizational routines (Huang & Newell, 2003). Table 3 shows the indicators of integration capability proposed and the authors that support these.

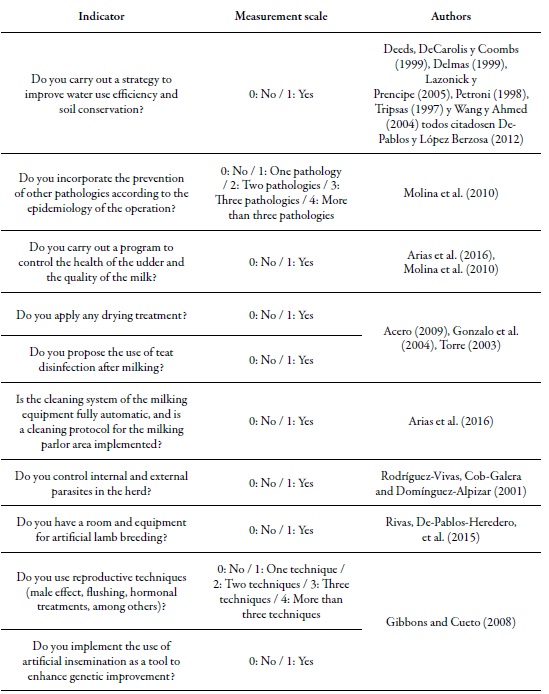

Measurement of innovation capability

The establishment of strategies to improve water use efficiency and soil conservation implies the introduction of innovative processes (Deeds et al., 1999; Delmas, 1999; Lazonick & Prencipe, 2005; Petroni, 1998; Tripsas, 1997; Wang & Ahmed, 2004, all cited by De-Pablos & López Berzosa, 2012) in livestock operations, aiming at being more efficient and reducing production unit costs, so it can be considered as an indicator of innovation capability.

To the extent that livestock farms incorporate the prevention of other pathologies according to the epidemiology of the operation, they will include improvements in the food, management and health areas (Molina, Yamaki, Berruga, Althaus, & Molina, 2010) and therefore, in processes whose purpose is the improvement of quality and production.

Arias et al. (2016), in their study on the integral quality of the manchego sheep milk, analyzed various livestock aspects and concluded that the presence of somatic cells affects the clotting time and hardness of the curd in milk. This has a direct influence on milk quality, as, at higher somatic cell count, the coagulation time is longer, obtaining lower hardness that reduces milk quality.

Based on the above, the establishment of a health control program of the udder and the milk quality introduces significant changes in the process of obtaining milk, to improve its quality and therefore, it is an indicator of innovation capability.

One of the most important aspects about the health of the sheep udder is mastitis, particularly clinical mastitis, which has the greatest impact on the profitability of livestock, as it causes a reduction in milk production and increases production costs by reducing the shelf life of the sheep. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the replacement rate of animals (Acero, 2009). Through the employment of techniques such as the drying treatment (Gonzalo, Tardáguila, De la Fuente, & San Primitivo, 2004) and the disinfection of the teat after milking as part of the cleaning protocol (Torre, 2003), the appearance of mastitis is reduced. For that reason, the introduction of these techniques is considered as process innovations.

Arias et al. (2012) analyze the impact of the lack of milking hygiene on the appearance of germs and butyric spores in milk, which affects the quality of milk and causes late swelling in cheeses. The introduction of automatic cleaning systems for milking equipment and the compliance with a cleaning protocol for the milking parlor area reduces the problems described above. Moreover, this implies an improvement in the process and are therefore included as an indicator of innovation capability.

Parasites have a negative effect on the development of sheep since they can cause diseases that also have a negative influence on the products obtained from sheep (Rodríguez-Vivas, Cob-Galera, & Domínguez-Alpizar, 2001). For that reason, the introduction of parasite controls is considered an innovation in the process to improve the performance of the entire operation.

As indicated by Rivas, De-Pablos-Heredero, Rangel and García (2015), the artificial breeding of lambs is an innovation that has not been adopted much. It is considered, therefore, that the variable “Do you have a room and equipment for artificial lamb breeding” is an indicator of innovation capability. Gibbons and Cueto (2008) pointed out that artificial insemination allows "conserving the genetic variability of the species subject to a continuous breeding process of its productive characteristics" (p. 3), which means the introduction of substantial changes in the productive process. For this reason, the variables “Do you use reproductive techniques” and “Do you implement the use of artificial insemination” will be used to measure innovation capability.

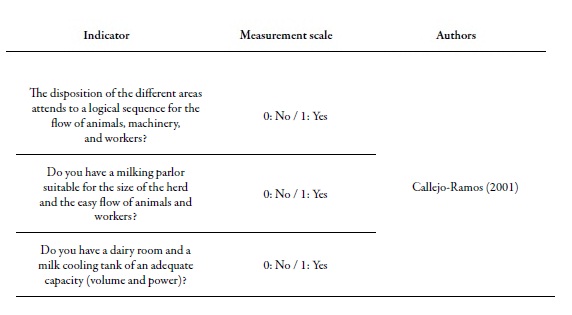

Callejo-Ramos (2001) indicates that adequate milking installations influence the maximization of milking performance and, therefore, the reduction in costs. To the extent that the provision of the milking parlor and, by extension, of the different areas of the farm facilitates animal flow and the more effective implementation of activities —and takes into account the appropriate dimension of the milking rooms as well as the dairy and refrigeration tank rooms— the costs incurred will be lower compared to those farms that have not considered this. Table 4 shows the indicators of innovation capability proposed and the authors that support these.

Conclusions

Although there is consensus in the academic literature on the importance of the development of dynamic capabilities to achieve sustainable competitive advantages over time, this review carried out on the measurement of dynamic capabilities reveals the diversity of studies in this field, without having defined indicators to measure these capabilities in practice.

In this work, applying the concepts of different types of dynamic capabilities of the sheep sector, 54 indicators were identified as adequate to perform this measurement. Therefore, this study offers a useful tool for the academic sector and the market that allows farms to measure their dynamic capabilities and compare them with other farms. This measurement will help them to develop active process improvement strategies to raise their market detection, absorption, integration and innovation capabilities, and in this way, improve their managerial performance and seek a better positioning in the sector.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the peer reviewers and the editors of this journal for their comments, which helped to improve this document.

REFERENCES

Acero, P. (2009). Planificación y manejo de la explotación de ovino de leche. Tomo IV. Junta de Castilla y León, España: Consejería de Agricultura y Ganadería. [ Links ]

Alfonso, M., Sañudo, C., Berge, P., Fisher, A. V., Stamataris, C., Thorkelsson. G., & Plasentier, E. (2001). Influential factors in lamb meat quality. Acceptability of specific designations. En R. Rubino & P. Morand-Fehr (Eds.), Production systems and product quality in sheep and goats (pp. 19-28). Zaragoza, España: Centre International de Hautes Études Agronomiques Méditerranéennes. [ Links ]

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33-46. doi:10.1002/smj.4250140105. [ Links ]

Angón, E., Perea, J., Toro-Mújica, P., Rivas, J., De-Pablos, C., & García, A. (2015). Pathways towards to improve the feasibility of dairy pastoral system in La Pampa (Argentine). Italian Journal of Animal Science, 14(4), 643 649. doi:10.4081/ijas.2015.3624. [ Links ]

Aragón, A., & Rubio, A. (2005). Factores asociados con el éxito competitivo de las pyme industriales en España. Universia Business Review, 8(4), 38-51. Recuperado de https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=43300803. [ Links ]

Araya-Leandro, A. (2017). Modelos de planeación estratégica en las empresas familiares. tec Empresarial, 11(1), 23-34. doi:10.18845/te.v11i1.3093. [ Links ]

Arias, C., Oliete, B., Seseña, S., Jimenez, L., Pérez-Guzmán, M. D., & Arias, R. (2012). Importance of on-farm management practices on lactate-fermenting Clostridium spp. spore contamination of Manchega ewe milk: Determination of risk factors and characterization of Clostridium population. Small Ruminant Research, 111, 120-128. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2012.11.030. [ Links ]

Arias, R., Gallego, R., Altares, S., Garzón, A., Romero, J., Jiménez, L., … Pérez-Guzmán, M. D. (2016). Calidad de la leche en ganaderías de ovino Manchego. Revisión. Archivos de Zootecnia, 65(251), 469-473. [ Links ]

Bravo-Ibarra, E. R., & Herrera, L. (2009). Capacidad de innovación y configuración de recursos organizativos. Intangible capital, 5(3), 301-320. doi:10.3926/ic.2009. v5n3.p301-320. [ Links ]

Byrd, T. A., & Davidson, N. W. (2003). Examining possible antecedents of it impact on the supply chain and its effects on firm performance. Information & Management, 41(2), 243-255. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00051-X. [ Links ]

Caballero, R. (2009). Stakeholder interactions in Castile-La Mancha, Spain’s cereal-sheep system. Agricultural Human Values, 26, 219-231. doi:10.1007/s10460-008-9157-6. [ Links ]

Callejo-Ramos, A. (2001). Diseño de instalaciones de ordeño. bovis. Aula Veterinaria, 99, 15-32. [ Links ]

Castilla La-Mancha (clm). (2015). Pacto por la recuperación económica de Castilla-La Mancha 2015-2020. Recuperado de: https://www.castillalamancha.es/gobierno/economiaempresasyempleo/actuaciones/pacto-por-larecuperaci%C3%B3n-econ%C3%B3mica-de-castilla-lamancha-2015-2020 [ Links ]

Collins, C., & Clark, K. (2003). Strategic Human Resource Practices, Top Management Team Social Networks, and Firm Performance: The Role of Human Resource Practices in Creating Organizational Competitive Advantage. The Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 740-751. doi:10.2307/30040665. [ Links ]

Cussó, X. (2005). El estado nutritivo de la población española 1900-1970. Análisis de las necesidades y disponibilidades de nutrientes. Historia Agraria, 36, 329-358. Recuperado de https://www.ddd.uab.cat/record/170715 [ Links ]

Daneels, E. (2010). Trying to become a different type of Company: Dynamic capability at Smith Corona. Strategic Management Review, 32, 1-31. doi:10.1002/smj.863. [ Links ]

De-Pablos, C., & López-Berzosa, D. (2012). La importancia de los mecanismos de coordinación organizativa en la excelencia del sistema español de trasplantes. Intangible Capital, 8(1), 17-42. doi:10.3926/ic.270. [ Links ]

De-Pablos, C., López-Hermoso, J. J., Martín-Romo, S., & Medina, S. (2013). Organización y transformación de los sistemas de información en la empresa (2.ª ed.). Madrid, España: esic. [ Links ]

Easterby-Smith, M., & Lyles, M. A (2011). Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Chichester, Inglaterra: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Ebers, M., & Maurer, I. (2014). Connections count: How relational embeddedness and relational empowerment foster absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 43, 318-332. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.017. [ Links ]

Gibbons, A., & Cueto, M. (2008). Manual de inseminación artificial en la especie ovina. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Bariloche, Argentina: Centro Regional Patagonia Norte. [ Links ]

González, R., & García-Muiña, F. E. (2011). Conceptuación y medición del constructo capacidad de absorción: hacia un marco de integración. Revista de Dirección y Administración de Empresas, 18, 43-65. Recuperado de https://www.ehu.eus/ojs/index.php/rdae/article/view/11292/10414 [ Links ]

González-Campo, C. H., & Hurtado, A. (2014). Influencia de la capacidad de absorción sobre la innovación: unanálisis empírico en las mipymes colombianas. Estudios Gerenciales, 30(132), 277-286. doi:10.1016/j.estger.2014.02.015. [ Links ]

Gonzalo, C., Tardáguila, J. A., De la Fuente, L. F., & San Primitivo, F. (2004). Effects of selective and complete dry therapy on prevalence of intramammary infection and on milk yield in the subsequent lactation in dairy ewes. Journal of Dairy Research, 71(1), 33-38. [ Links ]

Guerras-Martín, L. A., & Navas-López, J. E. (2015). La dirección estratégica de la empresa. Teoría y aplicaciones. Cizur Menor, España: Thomson-Reuters-Cívitas. [ Links ]

Huang, J. C., & Newell, S. (2003). Knowledge integration processes and dynamics within the context of cross-functional projects. International Journal of Project Management, 21, 167-176. Recuperado de https://www.ask-force.org/web/Discourse/Huang-Knowledge-Integration-2003.pdf [ Links ]

Li, P. P. (2007). Social tie, social capital and social behavior: toward an integrative model of informal exchange. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(2), 227-246. doi:10.1007/s10490-006-9031-2. [ Links ]

Materia, V., Pascucci, S., & Dries, L. (2017). Are In-House and Outsourcing Innovation Strategies Correlated? Evidence from the European Agri-Food Sector Journal of Agricultural Economics, 68(1), 249-268. doi:10.1111/1477-9552.12206. [ Links ]

Milán, M. J., Caja, G., González-González, R., Fernández-Pérez, A., & Such, X. (2011). Structure and performance of Awassi and Assaf dairy sheep farms in northwestern Spain. Journal of Dairy Science, 94, 771-78. doi:10.3168/ jds.2010-3520. [ Links ]

Minbaeva, D., Pedersen, T., Bjorkman, I., Frey, C., & Park, H. (2003). mnc knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and hrm. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(6), 586-599. doi:10.1057/palgrave. jibs.8400056. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (Mapama). (2015). Caracterización del sector ovino y caprino en España año 2015. Subdirección General de Productos Ganaderos. Recuperado de https://www.mapama.gob.es/es/ganaderia/temas/produccion-y-mercados-ganaderos/ [ Links ]

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (Mapama). (2018). Resumen semestral indicadores ovino de leche. Subdirección General de Productos Ganaderos. Recuperado de https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ganaderia/estadisticas/dashboardovinodeleche_feb2018_tcm30-443514.pdf [ Links ]

Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural Marino (marm) (2011). Programa de Mejora de la raza ovina manchega. Recuperado de https://www.agrama.org/documentos/PROGRAMA%20DE%20MEJORA%202011.pdf [ Links ]

Molina, A., Yamaki, M., Berruga, M. I., Althaus, R. L., & Molina, P. (2010). Management and sanitary practices in ewe dairy farms and bulk milk somatic cell count. Spanish Journal Agricultural Research, 8, 334-341. doi:10.5424/ sjar/2010082-1213. [ Links ]

Monferrer, D., Blesa, A., & Ripollés, M. (2013). Orientación al mercado de la red y capacidades dinámicas de absorción e innovación como determinantes del resultado internacional de las nuevas empresas internacionales. Revista Española de Investigación de Marketing ESIC, 17(2), 29-52. doi:10.1016/S1138-1442(14)60023-1. [ Links ]

Morantes, M., Dios-Palomares, R., Peña, M. E., Rivas J., Perea J., & García-Martínez, A. (2017). Management and productivity of dairy sheep production systems in the Castilla-La Mancha, Spain. Small Ruminant Research, 149, 62-72. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2017.01.005. [ Links ]

Murovec, N., & Prodan, I. (2009). Absorptive capacity, its determinants, and influence on innovation output: Cross-cultural validation of the structural model. Technovation, 29(12), 859-872. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2009.05.010. [ Links ]

Nieves, J. (2014). Relaciones sociales, capacidades dinámicas e innovación: un análisis empírico en la industria hotelera. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 23(4), 166-174. doi:10.1016/j.redee.2014.09.002. [ Links ]

Okhuysen, G. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2002). Integrating knowledge in groups: How formal interventions enable flexibility. Organization Science, 13(4), 370-386. doi:10.1287/ orsc.13.4.370.2947. [ Links ]

Petter, S., Delone, W., & McLean, E. R. (2012). The Past, Present, and Future of "IS Success". Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(Special Issue), 341 362. doi:10.17705/1jais.00296. [ Links ]

Rivas, J., Perea, J., Angón, E., Barba, C., Morantes, M., Dios-Palomares, R., & García, A. (2015). Diversity in the dry land mixed system and viability of dairy sheep farming. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 14(2), 179-186. doi:10.4081/ijas.2015.3513. [ Links ]

Rivas, J., De-Pablos-Heredero, C., Rangel, J., & García, A. (2015). Innovación tecnológica en ganadería. Control de procesos. En Murillo, G., García, A., & Lara, M.: Gestión sustentable de empresas agroalimentarias. Factores clave de estrategia competitiva (pp. 145-168) Quito, Ecuador: Quevedo. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Vivas, R. I., Cob-Galera, L. A., & Domínguez-Alpizar, J. L. (2001). Frecuencia de parásitos gastrointestinales en animales domésticos diagnosticados en Yucatán, México. Revista Biomédica, 12(1), 19-25. [ Links ]

Rubino, R., Pizzillo, M., & Masoero, G. (2010). Calidad del producto en relación con los sistemas de pastoreo. III Congreso de Producción Animal Tropical, 5(118). acpaica-focal, La Habana, Cuba. [ Links ]

Ryschawy, J., Choisis, N., Choisis, J. P., Joannon, A., & Gibon, A. (2012). Mixed crop-livestock systems: an economic and environmental-friendly way of farming? Animal, 6(10), 1722-1730. doi:10.1017/S1751731112000675. [ Links ]

Ryschawy, J., Choisis, N., Choisis, J. P., Joannon, A., & Gibon, A. (2013). Paths to last in mixed crop-livestock farming: lessons from an assessment of farm trajectories of change. Animal, 7(4), 673-681. doi:10.1017/S1751731112002091. [ Links ]

Shahbazi, R., Haghshenas, M., Nassiriyar, M., & Sadeghzadeh, A. (2016). Methodology Presentation for the Integration of Knowledge Management and Business Intelligence. International Journal of Service Science, Management and Engineering, 3(5), 26-31. [ Links ]

Teece, D., & Pisano, G. (1994). The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: An Introduction. Industrial and corporate change, 3(3), 537-556. doi:10.1093/icc/3.3.537-a. [ Links ]

Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533. [ Links ]

Torre, E. (2003). Tratamiento y control de mamitis ovinas. Mundo ganadero, 155, 56-60. [ Links ]

Wang C. L., & Ahmed P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: a review and research agenda. The International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(1), 31-51. doi:10.1111/j.14682370.2007.00201.x. [ Links ]

Received: October 04, 2018; Accepted: February 18, 2019

texto em

texto em