Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria

versão impressa ISSN 0122-8706versão On-line ISSN 2500-5308

Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecuaria vol.21 no.2 Mosquera maio/ago 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol21_num2_art:1298

Biophysical resources

Partial substitution of corn for wholegrain Cucurbita moschata flour and its effect on the productive variables of Cobb 500 chickens

1Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Portoviejo, Ecuador.

2Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Portoviejo, Ecuador.

3Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Portoviejo, Ecuador.

4Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Palmira, Colombia.

5Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Portoviejo, Ecuador.

6Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Portoviejo, Ecuador.

Wholegrain Cucurbita moschata flour has a high total carotenoid content that can contribute to the tarsal and skin pigmentation of broilers. The aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of the substitution of corn for wholegrain pumpkin flour at three levels (10 %, 12 %, and 15 %) on the productive yield and pigmentation of chickens. A completely randomized experimental design was used with four treatments and four repetitions, each with 15 chickens of the Cobb 500 line without sexing. The productive variables weight, weight gain, food consumption, accumulated consumption, conversion and pigmentation of the skin, and tarsus of chickens were evaluated. The latter employed the Konica-Minolta CR-300 colorimeter. The analysis of variance performed on the variables consumption, accumulated consumption, weight gain, and accumulated weight showed statistical differences (p< 0.05) in the first and second stages between treatments. In the final stage, after 42 days, no significant differences between the studied variables were found, reaching a weight of 2,232.22 g to 2,384.00 g per chicken. The results in terms of skin and tarsus pigmentation show that the inclusion of 15 % wholegrain pumpkin flour showed significant differences between the T0 and the T2 treatments. We conclude that the use of wholegrain flour in its different formulations achieved satisfactory results; furthermore, 15 % of this flour was favorable on the productive yields and pigmentation of the chickens.

Keywords broiler chickens; carotenoids; Cucurbitaceae; flours; weight gain

La harina integral de Cucurbita moschata posee un alto contenido de carotenoides totales que pueden contribuir a la pigmentación del tarso y la piel de pollos de engorde. El objetivo de la investigación fue evaluar el efecto de la sustitución de maíz en tres niveles por harina integral de zapallo (10 %, 12 % y 15 %) sobre el rendimiento productivo y la pigmentación de los pollos. Se utilizó un diseño experimental completamente al azar con cuatro tratamientos y cuatro repeticiones, cada una con 15 pollos de la línea Cobb 500 sin sexar. Se evaluaron las variables productivas de peso, ganancia de peso, consumo de alimento, consumo acumulado, conversión y pigmentación de piel y tarsos de los pollos con el uso del colorímetro Konica-Minolta CR-300. Los análisis de varianza de las variables consumo, consumo acumulado, ganancia de peso y peso acumulado presentaron diferencias estadísticas (p <0,05) en las etapas primera y segunda entre los diferentes tratamientos. En la etapa de finalización, luego de 42 días, no se observaron diferencias significativas entre las variables estudiadas y se alcanzó un peso de 2 232,22 g a 2 384,00 g por pollo. Los resultados sobre la pigmentación de piel y tarsos muestran que la inclusión del 15 % de harina integral de zapallo generó diferencias significativas entre el tratamiento T0 y el tratamiento T2. Se concluye que la utilización de harina integral de zapallo en sus diferentes formulaciones logró resultados satisfactorios; sin embargo, el 15 % de esta harina resultó favorable sobre los rendimientos productivos y la pigmentación de los pollos.

Palabras clave carotenoides; Cucurbitaceae; ganancia de peso; harinas; pollo de engorde

Introduction

In the world today, intensive broiler farming is increasingly conditioned by factors, such as the genetic improvement of animals in terms of their growth speed, the use of feed and the increasing intensification of breeding, which leads to increasing the density in farms and, therefore, demands an improvement in their handling (Blajman et al., 2015; Parra et al., 2017).

In Ecuador, the poultry sector shows a promising future due to the high acceptance of the products of this activity, such as meat and eggs (Aguilera, 2014). The demand for these products is directly related to their nutritional contribution and price affordability (Galarza et al., 2016). However, from a consumer perspective, other aspects are considered, such as good appearance, specific sensory characteristics, and an adequate classification of the carcass (Attia et al., 2016).

In industrial poultry farming, supplementation of synthetic carotenoids in the daily diet of broilers is a frequent practice established by the requirements of the commercialization channels (Meza et al., 2018; Rajput et al., 2012). The level of inclusion of dietary pigment for broilers varies by company, region, and country (Frade-Negrete et al., 2016).

In this sense, the pigmentation of the skin of the carcass and the tarsus of chicken is, in many cases, a decisive characteristic for the choice or rejection of the product by the consumer (Campo et al., 2017). Synthetic carotenoids have been used to achieve ideal pigmentation, which increases the cost of feed without adding nutritional qualities and also without affecting the ability of consumers to buy the product (Shimada, 2010).

Concerning the sources of natural origin carotenoids that are included in the feeding of broilers, different works show the use of raw materials such as pumpkin (C. moschata) and corn (Zea mays) (Carvajal-Tapia et al., 2017; Nieves, 2015; Ubaque et al., 2015). The use of other sources, such as achiote (Bixa orellana), turmeric (Curcuma longa), African marigold (Tagetes erecta), and sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum), have also been documented (Valentim et al., 2019). According to Mascarell and Carné (2011), natural pigment is not produced on a large scale due, in most cases, to the shortage of the main raw materials, unlike synthetic pigment, which has greater accessibility and a relative low cost in the market (Zambrano et al. 2017).

In Ecuador, pumpkins are cultivated in the Costa region [coastal region], especially in the province of Manabí, with a total of 11 622 ha and a production of approximately 12 577 Tm. The species Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir (cv. Macre) is one of the most cultivated because it is a rustic vegetable that does not require much care; however, during the most significant harvest period for this species, its price decreases and much of the production is lost (Mendoza et al., 2019).

Pumpkin is a source of natural carotenoids such as α- and β-carotene and lutein —also called carotenoid vitamin—, which has a close relationship with β-carotene and vitamin A and is an important source of carbohydrates (Alemán et al., 2017; Rodríguez et al., 2018). This could be an alternative to achieve good pigmentation of broilers and maintain their quality for distribution and commercialization, without resorting to artificial pigments used by the poultry industry (Bilgili & Hess, 2010).

Accordingly, the aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of the partial substitution of corn with wholegrain pumpkin flour at three levels on the productive variables and the adhesion of pigments in the tarsus and skin of broilers.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out at Facultad de Ciencias Zootécnicas [Faculty of Zootechnical Sciences] of Universidad Técnica de Manabí, located in the city of Chone, province of Manabí, Ecuador, at the following coordinates: latitude 00º41ʹ18.55ʺ S, and longitude 00º 13ʹ26.67ʺ W. It is located at an altitude of 16 m a.s.l., it has a precipitation of 665 mm, an evaporation of 1,407 mm, a maximum temperature of 34 °C and a minimum of 19.3 °C in average (Google Earth, s. f.).

Pumpkin, Cucurbita moschata cv. Macre fruits used in this study were acquired in a semi-mature state in the Chone canton. Fruits were washed and pre-cut into large slices of 3 mm thick with an Inmegar 2006317 slicer, model Iram Lr 38324, made in Ecuador. The fruit was then dehydrated with the husks and seeds employing an electric dehydrator (Inmegar Dryer 300417, model IEF-14, made in Ecuador (35cm [14”] in size, with a capacity of 10 trays)), which has a sensor that allows dehydration without exceeding 60 °C of temperature. The dehydration time was six hours, after which milling was carried out with an electric mill (Inmegar 01051, model W112M 220\240V, made in Ecuador and with a capacity of 40 kg).

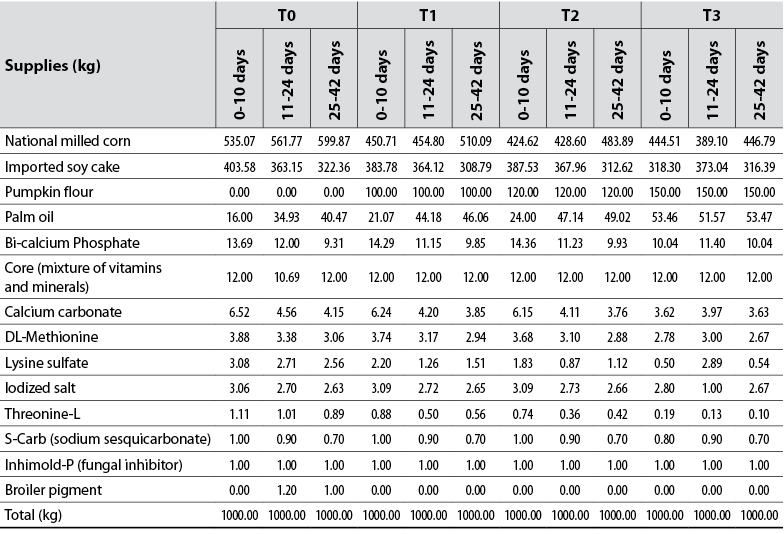

The balanced feed was produced in the feed factory of Facultad de Ciencias Zootécnicas de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí, under the nutritional requirements that the Cobb 500 commercial line requires for this type of breeding. Three types of diets were formulated using the Allix software (version S2) provided by EcuadPremex and based on the three chicken breeding stages: initial (1-14 days), growth (14-28 days), and final (28-42 days) (table 1). The food was restricted during certain times of the day when the temperature was extreme; in this case, it was supplied overnight when the temperature had decreased.

Table 1 Formulation of the three types of feed based on 1,000 kg of balanced food

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the Allix software

The fieldwork was carried out employing a completely randomized experimental design that included four treatments and four repetitions with a total of 240 unsexed chickens of the Cobb 500 commercial line, which were distributed in 16 experimental units with 15 chickens per unit. Each treatment comprised a space of 50 m² long by 10 m² wide, and treatment distribution had a density of eight chickens per square meter. The treatments were T0 (control with corn and xanthophyll pigment (synthetic pigments) in a concentration of 4 %), T1 (partial substitution of corn for 10 % of wholegrain pumpkin flour [WPF]), T2 (partial substitution of corn with 12 % of WPF), and T3 (partial replacement of corn with 15 % of WPF).

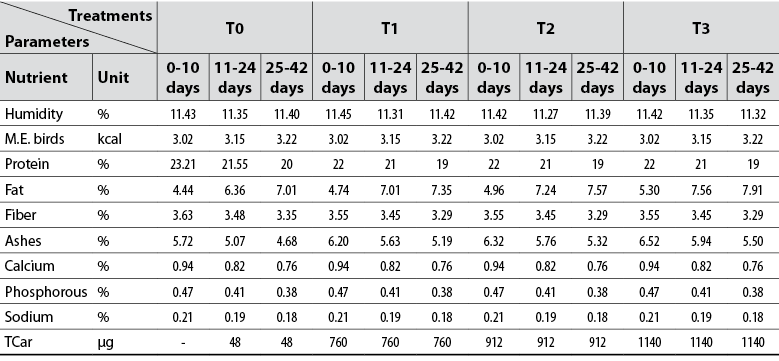

For the chemical analysis of the diets to be balanced for the three breeding stages (table 2), the Weende protocol was applied, where protein, fat, dry matter, fiber and nitrogen-free extract were established (Carrier et al., 2011). Through the Van Soest protocol, neutral detergent fiber and acid detergent fiber were identified (Van Soest, 1963). Gross energy and dry matter were defined according to the parameters established by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2000). The profiles for organic nutrients and essential and non-essential amino acids were carried out through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Koller et al., 1984). An HPLC device of the Thermo Fisher Scientific brand, Accela Autosampler model, was used. Total carotenoids (TC) were evaluated using the methodology of Liaaen-Jensen and Jensen (1997), also applying a UV light spectrophotometer.

C = A × V × f × 10/2,500

Where C: quantity of carotenoids in mg; A: absorbance (0.382 as the average of three replicates); V: final volume in milliliters (0 mL); F: dilution factor (in this case it was 1); 10: factor for unit transformation, and 2,500: average extinction coefficient for carotenoids under absorbance reading conditions.

Table 2 Nutritional values of chicken diets

Ttreatments

Pparameters

M.E.metabolizable energy

TCartotal carotenoids

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the Allix software

A contactless KKmoon thermometer with a digital infrared laser and a measuring range from -50 °C to 380 °C was used to control the temperature of the chicken shed. Besides, curtains were placed to maintain the environmental shed conditions stable during the first 15 days of bird development.

Once the newborn chickens were received (one day of birth), they were weighed individually to establish their initial weight as the reference point for the productive variables. A digital electronic scale of 60 kg capacity was used with an accuracy of 0.01 kg, model MSA1202S-100-D0 (Sartorius brand). Weight control was carried out weekly during the 42 days that the birds were kept in the shed. Each repetition had a broiler feeder and an automatic drinking fountain. The productive variables for each treatment (food consumption, accumulated food consumption, weight gain, accumulated weight, food conversion, and skin and tarsus pigmentation) were evaluated at the end of each stage.

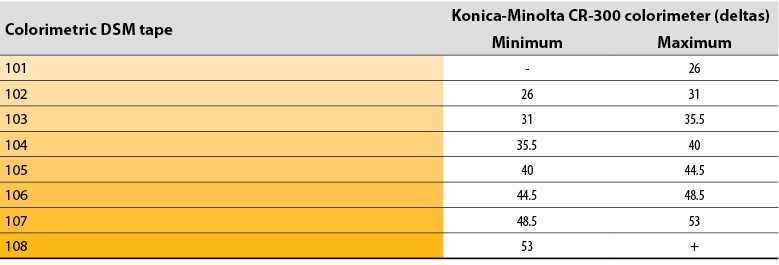

The Konica Minolta CR-300 colorimeter was used to evaluate pigmentation in tarsus and skin. The equipment was calibrated with the DSM colorimetric spectrum according to the equivalence table (table 3). This procedure was carried out when the birds were 42 days old, before slaughter. Five samples were taken for each repetition. The tarsus was measured in their lower end as required by the device, and the skin color was measured at the beginning of the wing (fat accumulation point).

Table 3 Equivalences of the DSM color spectrum in the Konica-Minolta CR-300 colorimeter

Source: Alzamora (2017)

In the analysis of results, the normality and homogeneity variance assumptions were applied for each variable under study using the statistical software InfoStat, version 24-03-2011. For multiple comparisons, post hoc tests were used; Tukey’s test was applied with a 95 % confidence interval.

Results and discussion

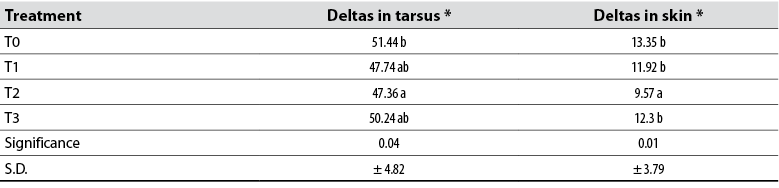

According to the data collected, the color of the tarsus and skin ranged between colors 106 and 107 of the DSM colorimetric spectrum. In Ecuador, the pigmentation requirement in the tarsus is equal to or higher than the color value 106 (table 4).

Table 4 Tarsus and skin coloration

*Means with one letter in common are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

T0control treatment

T1inclusion of 10 % of WPF

T2inclusion of 12 % of WPF

T3inclusion of 15 % of WPF

Source: Elaborated by the authors

These results demonstrate that the treatments in which WPF replaced corn, pigmented the tarsus and the skin of the chickens satisfactorily. The T0 treatment was the one with the highest score compared to the WPF-based treatments. The T3 treatment showed the best adhesion of xanthophylls in tarsus and skin in contrast to the other treatments that used WPF. Due to metabolism absorption processes, xanthophylls lodge in the epidermis (Moreno, 2014). The contribution of WPF is 0.0764 mg of the total carotenoids; that is, a total of 76.4 mg of carotenoids per kilogram of flour (Mendoza et al., 2019).

As the concentration of flours increased, the coloration in the skin of the chickens was similar to the formulation containing the synthetic pigment. Campo et al. (2017) specify that the concentration of carotenoids in the food is decisive to obtain a higher coloration on the skin, due to the accumulation of xanthophyll compounds in fats (Cortés-Cuevas et al., 2015; Oviedo & Wineland, 2013). On the other hand, Brenes-Soto (2014) states that the percentages of synthetic carotenoids in the daily ration of birds should not be significantly increased, as this may have an impact on health.

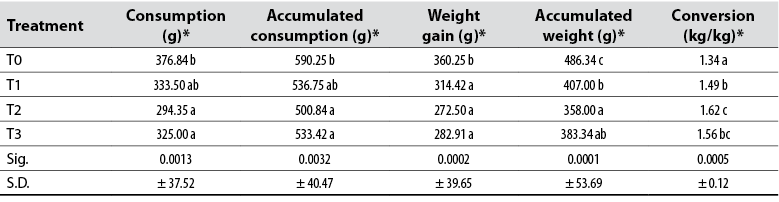

Although the color of the skin is lower compared to the one in the tarsus, scores higher than or equal to 11 are acceptable for commercialization. Ubaque et al. (2015) recorded a score of 6.39 against 0 in the pigmentation of chickens based on the Roche scale, which they attribute to the use of pumpkin meal. On the other hand, Carvajal-Tapia et al. (2017) recorded a score of 103 and 104 in the pigmentation of chickens of this same line fed with wholegrain pumpkin flour, which was explained by the presence of carotenoids in the pumpkin (C. moschata cv. Macre). However, when visually comparing the results using the DSM colorimetric spectrum, Carvajal-Tapia et al. (2017) found significant differences in treatments T0, T1, and T3. In this research, only differences in the T2 treatment compared to the others were evidenced. Table 5 shows the results of the productive development of the chickens during the initial stage.

Table 5 Statistical comparison of the productive variables in the initial stage (1-14 days)

*The means with one letter in common are not significantly different (p> 0.05).

Sigsignificance

T0control treatment

T1inclusion of 10 % of WPF

T2inclusion of 12 % of WPF

T3inclusion of 15 % of WPF

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Significant differences (p< 0.05) were observed between the variables studied in relation to the treatments; this may be due to the assimilation of the WPF provided in the different diets. However, despite its energy content, WPF had no side effects on chickens during this stage. This coincides with the works of Carvajal-Tapia et al. (2017) and Saldaña et al. (2016), who documented the use of pumpkin meal without side effects on the productive yield of the birds despite their energy content. On the other hand, the weight gain was higher in the T1 treatment (WPF 10 %) with an average of 360.25 g, a result similar to those reported by Andrade-Yucailla et al. (2017) and Medina et al. (2014), who recorded an average weight of 342.09 g to 354.22 g during this breeding stage. The productive behavior of the chickens during the growth stage is shown in table 6.

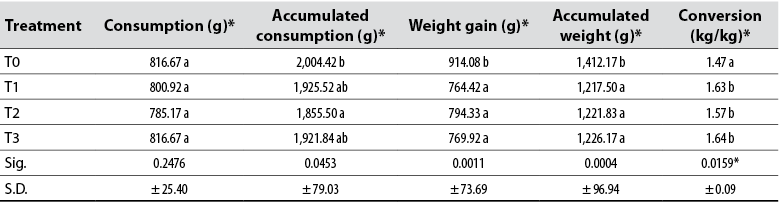

Table 6 Statistical comparison of the productive variables in the growth stage (14-28 days)

*The means with one letter in common are not significantly different (p> 0.05).

Sigsignificance

T0control treatment

T1inclusion of 10 % of WPF

T2inclusion of 12 % of WPF

T3inclusion of 15 % of WPF

Source: Elaborated by the authors

The results show significant differences (p< 0.05) in the variables accumulated consumption, weight gain, accumulated weight, and food conversion. Food consumption showed no significant differences (p> 0.05) between treatments. The highest yields in weight gain and accumulated weight are observed in the T0 treatment, which may be due to the diet with commercial balanced feed (Aguilar et al., 2018); however, during the final stage (table 7), favorable results are shown in the productive yield of the chickens compared to the different diets.

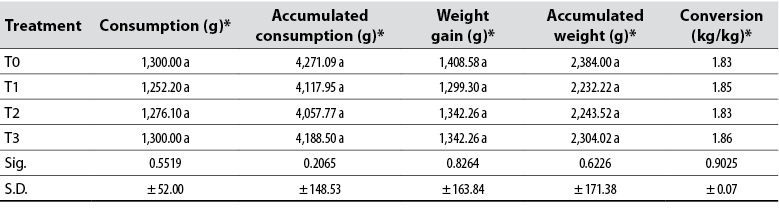

Table 7 Statistical comparison of the productive variables in the final stage (28-42 days)

*The means with one letter in common are not significantly different (p> 0.05).

Sigsignificance

T0control treatment

T1inclusion of 10 % of WPF

T2inclusion of 12 % of WPF

T3inclusion of 15 % of WPF

Source: Elaborated by the authors

The analysis of variance of the data obtained at 42 days after the Tukey test was carried out, shows that there are no significant differences (p> 0.05) between the evaluated variables of each of the treatments applied. These results are similar to those obtained by Carvajal-Tapia et al. (2017), who included pumpkin pulp flour in the feeding of broilers without observing significant differences in the productive variables. On the other hand, Alvarado et al. (2018) recorded significant differences in the variables accumulative consumption and weight gain between treatments applied with different types of commercial feed.

The statistical analysis of food conversion did not show significant differences (p> 0.05) between treatments. This may be due to the low fiber content of the WPF, allowing its easy digestion (Cadillo et al., 2019; Campo et al., 2017; Gonzáles et al., 2013). However, some researchers mention that food assimilation may show particular differences due to the digestive functioning of animals (Paredes et al., 2017).

A study carried out by Mendiola and Rojas (2015) with moringa as an alternative source in broiler feeding established significant differences (p> 0.05) between treatments; an average conversion of 2.02 kg/kg with conventional foods and of 2.28 with moringa, in the same line of chickens used in the current research. This may be associated with the fiber content available in moringa (Rumiche et al., 2018).

The weight accumulated in the finalization stage of the chickens did not show significant differences (p< 0.05) between the means of each treatment, ranging from 2,384.00 g to 2,232.22 g. These figures coincide with the results of Vega and Aguirre (2013), who did not obtain significant differences between the treatments applied in broilers. Based on all of the above, WPF can be considered as a natural food source rich in carotenoids and ascorbic acid, components that play an essential role in nutrition (Saeleaw & Schleining, 2011).

Conclusions

The use of wholegrain pumpkin flour proved to be efficient in the natural pigmentation of broilers without affecting their productive performance. The possibility of including this compound in the poultry food industry provides opportunities for the agricultural sector to conserve the harvest of C. moschata in times of low demand and, after processing, offer their product to the poultry sector.

Acknowledgments

To Universidad Técnica de Manabí for funding and giving their support to this research. To the reviewers for their contribution to improving the quality of the manuscript. To the company EcuadPremex, for providing the software for the formulation and establishing the physicochemical analysis of the balanced diets.

REFERENCES

Aguilera, M. (2014). Determinantes del desarrollo en la avicultura en Colombia: instituciones, organizaciones y tecnología. Revista del Banco de la República, 87(1046), 214. http://bit.ly/3aXsRin [ Links ]

Aguilar, J., Zea, O., & Vílchez, C. (2018). Rendimiento productivo e integridad ósea de pollos de carne en respuesta a suplementación dietaria con cuatro fuentes de fitasa comercial. Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú, 29(1), 169-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v29i1.14078 [ Links ]

Alemán, R., Bravo, C., Socorro, A., & García, R. (2017). Desarrollo del zapallo (Cucurbita maxima) con sistema de fertilización mineral y orgánica en las condiciones de la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Revista Científica Agroecosistemas, 5(1), 169-175. https://aes.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/aes/article/view/154/188 [ Links ]

Alvarado, H., Guerra, L., Vásquez, R., Ceró, A., Gómez, J., & Gallón, E. (2018). Comportamiento de indicadores productivos en dos líneas de hembras broilers con dos sistemas de alimentación en condiciones ambientales del trópico. Revista de Producción Animal, 30(3), 6-13. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/rpa/v30n3/rpa02318.pdf [ Links ]

Alzamora, E. (2017). Evaluación del efecto de un pigmento orgánico presente en harina de zanahoria, (Daucus carota) sobre la coloración en carcasas de pollos broiler [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad de las Américas]. Repositorio Digital Universidad de las Américas. http://bit.ly/3aQtolW [ Links ]

Andrade-Yucailla, V., Toalombo, P., Andrade-Yucailla, S., & Lima-Orozco, R. (2017). Evaluación de parámetros productivos de pollos broilers Coob 500 y Ross 308 en la Amazonía de Ecuador. REDVET. Revista Electrónica de Veterinaria, 18(2), 1-8. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/636/63651262008.pdf [ Links ]

Association of Official Analytical Chemists. (2000). Official methods of analysis of AOAC International (17 Ed.). [ Links ]

Attia, Y. A., Al-Harthi, M. A., Korish, M. A., & Shiboob, M. M. (2016). Evaluación de la calidad de la carne de pollo en el mercado minorista: efectos del tipo y origen de las canales. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias, 7(3), 321-339. http://bit.ly/2u48387 [ Links ]

Bilgili, S. F., & Hess, J. B. (2010). Problemas de piel en la canal de pollo: causas y soluciones. Selecciones Avícolas, 52(1), 13-18. http://bit.ly/2O6gVAH [ Links ]

Blajman, J., Zbrun, M., Astesana, D., Berisivil, A., Romero, A., Fusari, M., Soto, L., Signorini, M., Rosmini, M., & Frizzo, M. (2015). Probióticos en pollos parrilleros: una estrategia para los modelos productivos intensivos. Revista Argentina de Microbiología, 47(4), 360-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ram.2015.08.002 [ Links ]

Brenes-Soto, A. (2014). Los carotenoides dietéticos en el organismo animal. Nutrición Animal Tropical, 8(1), 21-29. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/nutrianimal/article/view/14907 [ Links ]

Cadillo, J., Cumpa, M., & Galarza, J. (2019). Rendimiento productivo y calidad de huevo en gallinas ponedoras alimentadas con torta de palmiste (Elaeis guineensis) y enzimas β-glucanasa y xilanasa. Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú, 30(2), 682-690. https://doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v30i2.16079 [ Links ]

Campo, J. M., Paz, L. J., & López, F. J. (2017). Utilización de chontaduro (Bactris gasipaes) enriquecida con Pleurotus ostreatus en pollos. Revista Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial, 15(2), 84-92. https://doi.org/10.18684/BSAA(15)84-92 [ Links ]

Carvajal-Tapia, J., Martínez-Mamián, C., & Vivas-Quila, N. (2017). Evaluación de parámetros productivos y pigmentación en pollos alimentados con harina de zapallo (Cucurbita moschata). Revista Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial, 15(2), 93-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.18684/BSAA(15)93-100 [ Links ]

Carrier, M., Loppinet-Serani, A., Denux, D., Lasnier, J-M., Ham-Pichavant, F., Cansell, F., & Aymonier, C. (2011). Thermogravimetric analysis as a new method to determine the lignocellulosic composition of biomass. Biomass and Bioenergy, 35(1), 298-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2010.08.067 [ Links ]

Cortés-Cuevas, A., Ramírez-Estrada, S., Arce-Menocal, J., Ávila-González, E., & López-Coello, C. (2015). Effect of feeding low-oil ddgs to laying hens and broiler chickens on performance and egg yolk and skin pigmentation. Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science, 17(2), 247-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-635x1702247-254 [ Links ]

Frade-Negrete, N. J., Hernández-Velasco, X., Fuente-Martínez, B., Quiroz-Pesina, M., Ávila-González, E., & Tellez, G. (2016). Effect of the infection with Eimeria acervulina, E. maxima and E. tenella on pigment absorption and skin deposition in broiler chickens. Archivos de Medicina y Veterinaria, 48(2), 199-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0301-732X2016000200010 [ Links ]

Galarza, J., Ortiz, H., & Toscano, C. (2016). Manejo de desechos orgánicos y cumplimiento de la normativa legal ambiental en las avícolas de la provincia de Tungurahua. Revista Digital de Medio Ambiente “Ojeando la Agenda”, 44. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5803856 [ Links ]

Gonzáles, S., Icochea, E., Reyna, P., Guzmán, J., Cazorla, F., Lúcar, J., Carcelén, F., & San Martín, V. (2013). Efecto de la suplementación de ácidos orgánicos sobre los parámetros productivos en pollos de engorde. Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú, 24(1), 32-37. https://doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v24i1.1653 [ Links ]

Google Earth. (s. f.). Ubicación geográfica de la Facultad de Ciencias Zootécnicas, Universidad Técnica de Manabí, Chone, provincia de Manabí, Ecuador. http://bit.ly/2uIfemt [ Links ]

Koller, J., Zaczek, R., & Coyle, T. (1984). N‐acetyl‐aspartyl‐glutamate: regional levels in rat brain and the effects of brain lesions as determined by a new hplc method. Journal of Neurochemistry, 43(4), 1136-1142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12854.x [ Links ]

Liaaen-Jensen, S., & Jensen, A. (1971). Quantitative determination of carotenoids in photosynthetic tissues. Methods in Enzymology, 23, 586-602. [ Links ]

Mascarell, J., & Carné, S. (2011). Pigmentantes naturales: combinación de xantofilas amarillas y rojas para optimizar su utilización en broilers. Selecciones Avícolas, 53(12), 13-16. http://bit.ly/38Qg2o1 [ Links ]

Medina, N. M., González, C. A., Daza, S. L., Restrepo, O., & Barahona, R. (2014). Desempeño productivo de pollos de engorde suplementados con biomasa de (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) derivada de la fermentación de residuos de banano. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y de Zootecnia, 61(3), 270-283. https://doi.org/10.15446/rfmvz.v61n3.46873 [ Links ]

Mendiola, J., & Rojas, R. (2015). Evaluación preliminar de la adición de moringa (Moringa oleífera) en la alimentación de pollos parrilleros. Universidad, Ciencia y Sociedad, 55(14), 55-62. http://bit.ly/2RB1SBe [ Links ]

Mendoza, F., Barre, R., Vargas, P., & Zambrano, L. (2019). Harina integral de zapallo (Cucurbita moschata) para alimento alternativo en la producción avícola. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Humanidades, Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología, 6(9), 668-679. https://doi.org/10.35381/cm.v5i9.256 [ Links ]

Meza, M., Hinojosa, F., & Lobo, R. (2018). Uso de pigmentantes naturales para la coloración de la yema de huevo y evaluación de parámetros productivos en aves de postura de la Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander Ocaña. Revista Colombiana de Zootecnia, 4(7). 38-42. http://anzoo.org/publicaciones/index.php/anzoo/article/view/28/19 [ Links ]

Moreno, M. (2014). Evaluación de la alimentación aviar (Gallus gallus domesticus) con maíz fortificado en carotenoides [Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Lleila]. https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/288367#page=1 [ Links ]

Nieves, A. (2015). Optimización de recursos en la explotación avícola (5.ª ed.). Editorial Elearning. [ Links ]

Oviedo, O., & Wineland, M. (2013). Manejo y nutrición de productoras que influyen en la salud y el desempeño en el pollo de engorda. En Asociación de Especialistas en Ciencias Avícolas del Centro de México, Memorias de la Sexta Reunión Anual AECACEM 2013, San Juan del Río, México, 20 al 22 de febrero de 2013 (pp. 220-232). http://bit.ly/2RYR1QP [ Links ]

Paredes, M., Vallejo, L., & Mantilla, J. (2017). Efecto del tipo de alimentación sobre el comportamiento productivo, características de la canal y calidad de carne del cerdo criollo negro cajamarquino. Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú, 28(4), 894-903. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v28i4.13879 [ Links ]

Parra, D., Parra, J., & Urdaneta, R. (2017). Efecto de un acidificante orgánico en los parámetros productivos de pollos de engorde. Revista Tecnocientífica URU, 12, 19-28. http://bit.ly/2O8s18A [ Links ]

Rajput, N., Naeem, M., Ali, S., Rui, Y., & Tian, W. (2012). Effect of dietary supplementation of marigold pigment on immunity, skin and meat color, and growth performance of broiler chickens. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola, 14(4), 233-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-635X2012000400009 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, R., Valdés, M., & Ortiz, S. (2018). Características agronómicas y calidad nutricional de los frutos y semillas de zapallo Cucurbita sp. Revista Colombiana de Ciencia Animal, 10(1), 86-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.24188/recia.v10.n1.2018.636 [ Links ]

Rumiche, E., Ramos, P., & Colca, I. (2018). Suplementación alimenticia con orégano (Origanum vulgare) y complejo enzimático en pollos de carne: I. Indicadores productivos. UCV - HACER: Revista de Investigación y Cultura, 7(1), 31-44. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6317321 [ Links ]

Saeleaw, M., & Schleining, G. (2011). Composition, physicochemical and morphological characterization of pumpkin flour. http://bit.ly/315vzgV [ Links ]

Saldaña, B., Gewehr, C., Guzmán, P., García, J., & Mateos, G. (2016). Influence of feed form and energy concentration of the rearing phase diets on productivity, digestive tract development and body measurements of brown-egg laying hens fed diets varying in energy concentration from 17 to 46 wk of age. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 221(Part A), 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.08.025 [ Links ]

Shimada, A. (2010). Nutrición animal. Editorial Trillas. [ Links ]

Ubaque, C., Orozco, L., Ortiz, S., Valdés, M., & Vallejo, F. (2015). Sustitución del maíz por harina integral de zapallo en la nutrición de pollos de engorde. Revista U. D. C. A. Actualidad y Divulgación Científica, 18(1), 137-146. https://doi.org/10.31910/rudca.v18.n1.2015.462 [ Links ]

Valentim, K., Bitttencourt, T., Lima, D., Moraleco, D., Tossuê, M., Silva, M., Vaccaro, B., & Silva, G. (2019). Pigmentantes vegetais e sintéticos em dietas de galinhas poedeiras negras. Boletim de Indústria Animal, 76, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.17523/bia.2019.v76.e1438 [ Links ]

Van Soest, P. J. (1963). Use of detergents in the analysis of fibrous feeds. ii. A rapid method for the determination of fiber and lignin. Journal of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists, 46(5), 829-835. http://bit.ly/2uMhTv7 [ Links ]

Vega, J., & Aguirre, R. (2013). Comparación de variables productivas entre macho y hembra en la producción de pollos parrilleros en el departamento de Santa Cruz. Universidad Ciencia y Sociedad,9, 39-47. http://www.revistasbolivianas.org.bo/pdf/ucs/n9/n9_a06.pdf [ Links ]

Zambrano, R., Gómez, J., Rodríguez, J., Alvarado, H., Quezada, L., Filian, W., Ponce, E., & Avellaneda, J. (2017). Evaluación de tres niveles de mananos oligosacáridos (Sacharomices cerevisae) en los parámetros productivos y salud intestinal en pollos de engorde en el Cantón Babahoyo, provincia de Los Ríos, Ecuador. European Scientific Journal, 13(12), 24-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n12p24 [ Links ]

Received: February 07, 2019; Accepted: December 27, 2019

texto em

texto em