Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria

versión impresa ISSN 0122-8706versión On-line ISSN 2500-5308

Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecuaria vol.21 no.2 Mosquera mayo/ago 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol21_num2_art:1374

Animal diet and nutrition

Characterization of the nutritional value of agro-industrial by-products for cattle feeding in the San Martin region, Peru

1Asistente de investigación, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

2Asistente de investigación, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

3Investigadora, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

4Estudiante de pregrado, Universidad Nacional de San Martín, Facultad Ciencias Agrarias, Escuela de Veterinaria. Tarapoto, Perú

5Docente, Universidad Nacional de San Martín, Facultad Ciencias Agrarias Escuela de Veterinaria. Tarapoto, Perú

6Docente, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

7Docente, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

8Docente, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Facultad de Zootecnia, Departamento Académico de Nutrición. Lima, Perú

The nutritional characterization of ten available agroindustrial residues in the San Martin region, Peru, was carried out. Nineteen residue samples were collected from 11 agroindustrial companies dedicated to oil palm, rice, cacao, coffee, coconut, and peach palm production. A proximal analysis was done to establish dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), ethereal extract (EE), crude fiber (CF), nitrogen-free extract (NFE), and ash. Besides, in vitro apparent dry matter digestibility (IVADMD), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), protein fractions, usable crude protein (uCP), total digestible nutrients (TDN) and net energy of lactation (NEL) were determined. Results showed significant differences between agroindustrial residues according their nutritional potential (p< 0.05), where rice in different sizes, i.e., < 1/4 grain size, > 1/4 grain size, and rice dust, were energetic inputs with high NEl (2.1 ± 0.02, 2.1 ± 0.02 and 1.7 ± 0.02 Mcal/kg dry matter, respectively) and IVADMD values (99.3 ± 0.25 %, 90.5 ± 0.42 % and 99.0 ± 0.68 %, respectively). Besides, the inputs with the highest protein contribution were coconut cake and cacao husk (21.9 % and 21.8 ± 1.34 % of CP, respectively). Palm fiber and rice husk were the fibrous residues with lower use potential due to their low IVADMD (27.8 ± 2.45 % and 27.7 ± 5.02 %, respectively) and high NDF (69.8 ± 4.17 % and 72.6 ± 6.45 %, respectively). Heart of palm husk showed moderated IVADMD (57.2 %) and high NDF (60.4 %) values. Agroindustrial residues of the San Martin region have a varied energy and protein use potential in cattle feeding.

Keywords by-products; cattle feeding; in vitro digestibility; nutritive value; protein

Se realizó una caracterización nutricional de 10 residuos agroindustriales disponibles en San Martín, Perú. Se colectaron 19 muestras de residuos provenientes de 11 plantas agroindustriales dedicadas a la producción de aceite de palma, arroz, cacao, café, coco y chontaduro. Se determinó la materia seca (MS), proteína cruda (PC), extracto etéreo (EE), fibra cruda (FC), extracto libre de nitrógeno (ELN), ceniza, digestibilidad aparente in vitro de la materia seca (DIVMS), fibra detergente neutro (FDN), fraccionamiento de proteína, proteína cruda utilizable (uCP), nutrientes digestibles totales (NDT) y energía neta de lactación (ENL). Se encontraron diferencias significativas entre subproductos con respecto a su potencial nutricional (p< 0,05), siendo el nielen, arrocillo y polvillo de arroz, insumos energéticos con valores altos de ENL (2,1 ± 0,02, 2,1 ± 0,02 y 1,7 ± 0,02 Mcal/kg en base seca, respectivamente) y alta DIVMS (99,3 ± 0,25 %, 90,5 ± 0,42 % y 99,0 ± 0,68 %, respectivamente). Insumos con mayor aporte proteico fueron torta de coco y cascarilla de cacao (21,9 % y 21,8 ± 1,34 % de PC, respectivamente). La fibra de palma y cascarilla de arroz fueron residuos fibrosos con menor potencial de uso por su baja DIVMS (27,8 ± 2,45 % y 27,7 ± 5,02 %, respectivamente) y alto contenido de FDN (69,8 ± 4,17 % y 72,6 ± 6,45 %, respectivamente). La cáscara de palmito tuvo regular DIVMS (57,2 %) y alto FDN (60,4 %). Los residuos agroindustriales de San Martín tienen un variado potencial energético y proteico de utilidad en la alimentación de ganado vacuno.

Palabras clave alimentación de ganado vacuno; digestibilidad in vitro; proteína; residuos; valor nutritivo

Introduction

Agroindustrial residues are the result of various physical, chemical and biological processes in the industrialization of animal or vegetable products, which usually do not have utility as a raw material for the production chain (Rosas, Ortiz, Herrera, & Leyva, 2016; Saval, 2012). These residues have been receiving great attention from farmers and researchers in animal science from a couple of decades ago due to its potential use in animal feed. Many agribusinesses that use agricultural raw materials produce residues that can be used as fuel, for animal feed or as fertilizers (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], 1997).

In several developing countries, agroindustrial and crop residues are often used as the main components of the diet in livestock, based on their local availability, the quality of the input and due to their low price (Mugerwa, Kabirizi, Zziwa, & Lukwago, 2012; Tingshuang, Sánchez, & Yu, 2002). Throughout the history of livestock, agroindustrial residues such as oil flour, bran, brewery and distillery grains, beet pulp and molasses, have been widely used. However, less conventional waste has currently greater availability, such as fruit and vegetable processing residues, serums, and culinary residues (Mirzaei-Aghsaghali & Maheri-Sis, 2008).

In the Peruvian Amazon, there is great biodiversity of crops that are currently undergoing industrialization processes; these generate unconventional residues that can be included in the diet of dairy and fattening cattle in the area. Among the industrialized products, fruits, vegetables, roots, seeds, leaves, tubers, and pods are included; some are sold fresh, transformed into nectars, juices, jams, salads, flours, oils, wines, powdered concentrates, and preserves, to name a few examples (Saval, 2012). Currently, there is a notable worldwide trend in the growth of residue production due to the increase in the processing of products for human consumption (Saval, 2012). To get an idea of the percentage of residues generated by the industries, palm oil uses only 9.0 % of the fruit components; the remaining 91.0 % is residue. The coffee industry uses 9.5 %, and the remaining 90.5 % is waste, and the cacao industry uses less than 10 %, and the rest is leftovers (Saval, 2012). Based on this availability, agroindustrial residues would be a good alternative as cattle feed, considering their nutritional composition, price, and time when these are used (Preston & Leng, 1987).

The chemical composition of these unconventional inputs of the tropics should be taken in a referential manner since animal response evaluations would necessarily be required (Preston & Leng, 1987). However, the methods and procedures used for the description of nutritional content, such as a proximal or Weende analysis, are highly accurate and have been extensively evaluated and validated, allowing their replication in new studies (Association of Official Analytical Chemists [AOAC], 2005). Likewise, knowledge of food digestibility is important for the formulation of ruminant rations (Bochi-Brum, Carro, Valdés, González & López, 1999). In that sense, in vitro methods to establish the digestibility of inputs (e.g., Goering & Van Soest, 1970) have been extensively studied, modified and validated with in vivo digestibility methods, allowing their application according to the accessibility of equipment (Giraldo, Gutiérrez, & Rúa, 2007).

The aim of this study was to carry out the nutritional characterization of 10 agroindustrial residues from the San Martín region in Peru, and based on this, classify them as potential inputs for cattle feeding in the tropics.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was conducted in the department of San Martín, Peru, specifically in the provinces of Moyobamba, Bellavista, Lamas, Rioja, Mariscal Cáceres, Picota, Tocache, and San Martín. The study areas, according to the ecological description of Holdridge (1987), belong to the Humid-Premontane Tropical Forest (bh-PT) life zone; it is characterized by presenting a tropical climate of rainy, semi-warm and humid savannas, with a minimum temperature of 10 °C and a maximum of 30 °C, with an average temperature of 22 °C throughout the year. The annual rainfall is 1,344 mm, occurring more frequently in March and April (106.5 mm) and with less rainfall in July and August (61.5 mm) (Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú [Senamhi], 2018).

Thirty-three agribusiness companies that process rice, oil palm, cacao, coffee, coconut, and peach palm were identified and surveyed in the different provinces mentioned above. Of the total number of companies contacted, 11 agreed to deliver residue samples to analyze their chemical and nutritional composition, as follows: Three rice plants (Comercial Agrícola El Progreso SRL, Molino San Nicolás SAC e Industria Molinera Amazonas SAC), one peach palm processing plant (Cooperativa Agroindustrial del Palmito), and two cacao processing companies (La Orquídea SAC, and Acopagro SAC). Moreover, two palm oil companies (Indupalsa SAC, and Palma del Espino SA), a coffee company (Olam SAC), and a coconut processing plant (Las Tres Rosas EIRL).

Processing residue samples

Agroindustrial residue identification and processing

Ten types of agroindustrial residues were obtained and assessed in this study. Four agroindustrial rice (Oryza sativa L. (Poaceae)) residues, including rice husk, split rice grain with < 1/4 grain size, split rice grain with > 1/4 grain size, and rice dust; one coffee (Coffea arabica L. (Rubiaceae)) residue: coffee pulp; one residue of cacao (Theobroma cacao L. (Malvaceae)): cacao husk; two oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq. (Arecaceae)) residues: palm fiber and palm kernel cake; one residue of coconut (Cocos nucifera L. (Arecaceae)): coconut cake; and one residue of peach palm or chontaduro (Bactris gasipaes Kunth (Arecaceae)): heart of palm husk.

The selection of these inputs was made based on their greater degree of availability (t/year) that allowed their relevant use by livestock in the area. For example, in the province of San Martín, about 33,000 t/year of rice dust is produced, 5,000 t/year of split rice with > 1/4 grain size, 5,000 t/year of split rice with < 1/4 grain size, and 84,000 t/year of rice husk. Furthermore, 9,000 t/year of coffee pulp, 3,000 t/year of cacao husk, 3,000 t/year of coconut cake, 33,000 t/year of palm fiber, 13,000 t/year of palm kernel cake, and 1,000 t/year of heart of palm husk, approximately (information collected through surveys in agroindustrial plants).

The samples of agroindustrial residues were taken during two consecutive days, obtaining a representative sample that was used for subsequent analyses. In some cases, samples of the same residue were taken at different processing sites (i.e., two or three different sources). The samples collected were the following: rice husk (2), split rice with < 1/4 grain size (3), rice dust (3), split rice with > 1/4 grain size (3), palm fiber (2), and cacao husk (2). In the case of palm kernel cake, coffee pulp, coconut cake and heart of palm husk, only one company was sampled for each of these residues assessed. Nineteen samples of all residues were analyzed.

Laboratory analysis

The establishment of the proximal chemical composition was carried out in Laboratorio de Evaluación Nutricional de Alimentos (LENA) [Nutritional Food Evaluation Laboratory] of Departamento Académico de Nutrición [Academic Department of Nutrition], Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM). The contents of dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), fat or ethereal extract (EE), crude fiber (CF), ash, and nitrogen-free extract (NFE) were measured according to the AOAC method (2005).

The establishment of the neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was carried out using the Ankom method (2017a): Neutral Detergent Fiber in feed - Filter bags technique, and in the case of the in vitro apparent dry matter digestibility (IVADMD), the Ankom method (2017b): Technology Method 3 - in vitro True Digestibility was used, employing the Daisy Incubator equipment. The rationale for this method is to establish incubation conditions similar to those that occur in vivo using solutions, such as minerals, nitrogen sources, and reducing agents that promote the anaerobiosis necessary in the process (Giraldo et al., 2007). The incubation process lasted 48 hours. Both tests were carried out in Laboratorio de Nutrición de Rumiantes, Departamento Académico de Nutrición [Laboratory of Nutrition of Ruminants, of the Academic Department of Nutrition], UNALM.

In addition, protein fractionation as a percentage of total protein was determined according to the methodology published by Licitra, Hernández and Van Soest (1996). In this method, fraction A represents non-protein nitrogen (NPN), which is soluble nitrogen in trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Fraction B1 is the rapidly degradable true protein established as a precipitable protein with TCA of the soluble protein in buffer minus the NPN. Fraction B2 is the true protein with an intermediate degradation rate, established as an insoluble protein in buffer minus the insoluble protein in neutral detergent. Fraction B3 is a slowly degradable true protein in neutral detergent determined as insoluble nitrogen (NDIP) minus fraction C. Fraction C is the protein not available or bound to the cell wall derived from insoluble nitrogen in acid detergent (Sniffen, O'Connor, Van Soest, Fox, & Russell, 1992). This analysis was performed on 14 residue samples in the Laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences in the Tropics, University of Hohenheim, Germany. Finally, the usable crude protein (uCP) of these samples was determined according to the equation of Zhao & Cao (2004).

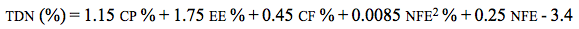

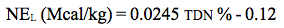

The estimation of total digestible nutrients (TDN) and the net energy of lactation (NEL) of each of the residues was obtained as proposed by Waller (2004). To the resulting value, 10 % was subtracted as a safety margin (Waller, 2004). TDN constitutes a unit of expression of the energy content in food, and when its value is known, other expressions of energy can be calculated using appropriate equations (Posada, Rosero, Rodríguez, & Costa, 2012). The NEL is a measure of the energy requirements of the milk produced and may vary according to its fat percentages (National Research Council [NRC], 1989). It should be noted that this equation has certain limitations concerning its use in unconventional tropical foods.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation of the nutritional results per agroindustrial residue, were used. Likewise, a completely randomized design (CRD) and Tukey’s means test (α = 0.05) were used to compare the results. The SAS (V8) statistical program was used for data processing.

Results and discussion

The results of the chemical composition and also of the in vitro apparent digestibility of the agroindustrial residues evaluated are shown in table 1. Ten agroindustrial residues were classified based on the results of the proximal analysis, neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and in vitro apparent dry matter digestibility (IVADMD). These analyses aided in the study of their nutritional characteristics and the possible substitution of one residue for another. There are different criteria for classifying inputs (Crampton & Harris, 1974; Ensminger, 1992; McDonald, Edwards, & Greenhalgh, 1981). One criterion that is a common denominator is to consider their nutritional contribution and, in this way, classify them as energy, protein, or fibrous foods.

Table 1 Chemical composition and in vitro digestibility of agroindustrial residues from the San Martín region Peru on a dry basis %

| Residues (origin) | DM % | CP % | EE % | ASH % | NFE % | NDF % | CF % | IVADMD % |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (Bellavista) | 88.8 | 9.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 88.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 98.5 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (Rioja) | 87.8 | 7.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 90.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 99.1 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (San Martín) | 88.5 | 10.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 89.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 99.3 |

| Heart of palm husk (Lamas) | 97.0 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 55.3 | 60.4 | 31.8 | 57.2 |

| Rice husk (Bellavista) | 97.2 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 16.1 | 33.9 | 77.1 | 47.0 | 24.1 |

| Rice husk (San Martín) | 97.2 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 13.2 | 38.6 | 68.0 | 44.1 | 31.2 |

| Cacao husk (Mariscal Cáceres) | 91.0 | 19.9 | 14.3 | 7.1 | 33.5 | 28.2 | 25.1 | 75.5 |

| Cacao husk (San Martín) | 91.1 | 23.6 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 24.6 | 28.7 | 32.3 | 77.4 |

| Palm fiber (Lamas) | 97.6 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 40.0 | 66.8 | 37.5 | 29.5 |

| Palm fiber (Tocache) | 97.1 | 7.1 | 3.3 | 6.4 | 43.8 | 72.7 | 39.4 | 26.0 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (Bellavista) | 87.7 | 9.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 90.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 99.6 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (Rioja) | 88.8 | 9.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 88.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 99.4 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (San Martín) | 88.2 | 10.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 88.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 99.1 |

| Palm kernel cake (Tocache) | 94.0 | 14.2 | 11.1 | 5.1 | 54.0 | 67.7 | 15.7 | 41.9 |

| Rice polishing (> 1/4 grain size) (Rioja) | 89.9 | 13.5 | 15.5 | 8.0 | 57.0 | 13.7 | 6.1 | 90.0 |

| Rice polishing (> 1/4 grain size) (San Martín) | 89.0 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 6.2 | 61.6 | 12.8 | 5.0 | 90.3 |

| Rice polishing (> 1/4 grain size) (Bellavista) | 89.2 | 15.2 | 15.9 | 8.6 | 55.0 | 12.8 | 5.2 | 91.3 |

| Coffee pulp (Moyobamba) | 94.3 | 12.9 | 2.4 | 5.8 | 64.3 | 37.2 | 14.6 | 79.3 |

| Coconut cake (Picota) | 92.4 | 21.9 | 16.4 | 6.8 | 40.4 | 51.7 | 14.6 | 5.02 |

Conventions:DM: dry matter; CP: crude protein; EE: ethereal extract; NFE: nitrogen-free extract; NDF: neutral detergent fiber; CF: crude fiber; IVADMD: in vitro apparent dry matter digestibility.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Agroindustrial energy residues were the byproducts from rice polishing, i.e., split rice grains (< 1/4 grain size), split rice grains (> 1/4 grain size), and rice dust. Moreover, coffee pulp and palm kernel cake were also found in this group. Net energy of lactation (NEL) ranged from 1.60 Mcal/kg (coffee pulp) to 2.19 Mcal/kg (split rice in the two grain sizes assessed) on a dry basis (table 2), and the IVADMD is in a range of 41.9 % (palm kernel cake) to 99.6 % (split rice with < 1/4 grain size). The values of NEL, EE, NFE, and in vitro digestibility of these residues were significantly higher than other residues (p< 0.05), confirming their energetic value. In vitro digestibility (IVADMD) of split rice (< 1/4 grain size) in this study was 99.4 ± 0.25 %; this value is due to the high content of nitrogen-free extract and the regular protein content (Reyes, 1991).

In the current study, split rice grains showed an average of 9.2 % crude protein, a higher value than what was reported by Shimada (2009), with 8.7 % of crude protein. According to Fundación Española para el Desarrollo de la Nutrición Animal [FEDNA] (2016a), rice dust is a good energy source for all farm species, especially for ruminants, due to its high fat content (12.0-18.0 %). The results obtained in this work on the level of fat coincide with what is stated in the literature. Regarding palm kernel cake, the ndf of 55.0-65.0 % is compensated with the fat content of 7.0-10.0 % (FEDNA, 2015). In contrast to the above, in the current study, a slightly higher content of 67.7 % was found with an ethereal extract level of 11.1 %, which must be related to differences in the agroindustrial process. Concerning crude protein, FEDNA (2015) reports a percentage of 16.7 %, i.e., higher to what was found in this study (14.2 %). The percentages of fat and protein in coffee pulp found in the current study (2.4 % and 12.9 %, respectively) were similar to those reported by Pandey et al. (2000), where fat and protein values were 2.5 % and 12.0 %, respectively.

Regarding agroindustrial protein residues, coconut cake and cacao husk were considered within this group because they have significantly higher levels of protein compared to other residues (p< 0.05). The average cacao husk protein was 21.8 %, and the one of the coconut cake was 21.9 %, while the IVADMD was 77.4 % and 52.0 %, respectively. However, the coconut cake stood out for showing a value of 51.7 % for NDF, while the cacao husk was 28.5 %, which coincides with the IVADMD values. The cacao husk protein level of the current study was higher than what has been reported by other studies where the level ranged between 15.0 % and 19.0 % (Cardona, Sorza, Posada, & Carmona, 2002; Lecumberri, Mateos, Izquierdo, Rupélez & Goya, 2007; Soto, 2012). With respect to the coconut cake, FEDNA (2016b) reported that the amount of crude protein in this input is 21.0 % with 90.9 % DM, percentages that agree with the results obtained in this work (21.8 % and 92.4 %, respectively). Besides, the in vitro digestibility of the coconut cake has been reported as limited by the high proportion of protein bound to the cell wall (70.0 %), as stated by FEDNA (2016b).

The residues classified as fibrous were rice husk, palm fiber, and heart of palm husk, containing levels of neutral detergent fiber (NDF) higher than the other inputs (p< 0.05). The NDF content of the rice husk varied in a range of 68.0-77.1 %, being lower than what Alemán (2012) found. This author reported a value of 78.5 % for NDF. On the other hand, the NDF content of palm fiber ranged from 66.8 % to 72.7 %, values similar to those reported by Cuesta, Conde and Moreno (2000), i.e., from 66.0 % to 77.0 %. The heart of palm husk showed a crude protein and fat values of 7.0 % and 1.3 %, respectively, lower values compared to those reported by Mosquera, Martínez, Medina & Hinostroza (2013) (i.e., 9.15 % protein and 5.15 % crude fat).

Table 2 shows the values for total digestible nutrients (TDN) and net energy of lactation (NEL). The fibrous residues show a low NEL value, e.g., rice husk with 0.8 Mcal/kg, compared to the energy residues that varied from 1.73 to 2.06 Mcal/kg of NEL (Split rice with > 1/4 grain size).

Table 2 Total digestible nutrients tdn and net energy of lactation ENL in agroindustrial residues in the San Martín region Peru on a dry basis %

| Residues (origin) | Estimation at 95 % | |

| TDN | NE L | |

| % | Mcal/kg | |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (Bellavista) | 87.30 | 2.02 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (Rioja) | 89.05 | 2.06 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) (San Martín) | 88.47 | 2.05 |

| Heart of palm husk (Lamas) | 54.95 | 1.23 |

| Rice husk (Bellavista) | 35.60 | 0.75 |

| Rice husk (San Martín) | 39.24 | 0.84 |

| Cacao husk (Mariscal Cáceres) | 66.35 | 1.51 |

| Cacao husk (San Martín) | 61.31 | 1.38 |

| Palm fiber (Lamas) | 53.15 | 1.18 |

| Palm fiber (Tocache) | 49.97 | 1.10 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (Bellavista) | 89.18 | 2.07 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (Rioja) | 88.22 | 2.04 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) (San Martín) | 87.58 | 2.03 |

| Palm kernel cake (Tocache) | 69.94 | 1.59 |

| Rice polishing (Bellavista) | 75.34 | 1.73 |

| Rice polishing (Rioja) | 75.48 | 1.73 |

| Rice polishing (San Martín) | 77.30 | 1.77 |

| Coffee pulp (Moyobamba) | 66.08 | 1.50 |

| Coconut cake (Picota) | 72.93 | 1.67 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

The residues with the greatest use potential in cattle feed due to the higher energy contribution are those obtained from rice milling, such as split rice with < 1/4 grain size, split rice with > 1/4 grain size, and rice dust (2.1 ± 0.02, 2.1 ± 0.02 and 1.7 ± 0.02 Mcal/kg of NEL on a dry basis, respectively); meanwhile, the protein contributions of the inputs with the greatest potential are coconut cake and cacao husk (21.9 % and 21.8 ± 1.34 % of dry-based protein, respectively). On the other hand, the residues with the lowest potential for use due to their low IVADMD value were palm fiber and rice husk (27.7 ± 2.47 % and 27.6 ± 5.02 %, respectively). In general, split rice with < 1/4 grain size was the agroindustrial residue with the best chemical and nutritional composition, as well as the best IVADMD in the current study.

The protein fractionation results are shown in table 3. The cacao husk showed a higher amount of fraction A (between 37.6 % and 43.8 %), indicating that this fraction of the input protein would be rapidly degraded in the rumen and converted into ammonia (Tham, Man, & Preston, 2008). The input that showed the highest amount of fraction C was the rice husk (between 44.1 % and 68.0 %). This input would have a higher amount of lignin, silica, tannin-protein complexes, or other products resistant to hydrolysis by microbial enzymes (Tham et al., 2008), which are directly linked to the amount of protein fraction C, being considered as a low-quality input.

Table 3 Protein fractioning of the agroindustrial residues of the San Martín region according to the methodology described by Sniffen et al 1992

| Residues (origin) | Protein fractions (%) | Utilizable crude protein | ||||

| A | B1 | B2 | B3 | C | (%) | |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) - Bellavista Province | 2.8 | 10.2 | 80.0 | 2.1 | 4.8 | 13.5 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) - Rioja Province | 6.2 | 8.3 | 75.5 | 0.2 | 9.9 | 10.1 |

| Split rice (> 1/4 grain size) - San Martín Province | 2.2 | 2.4 | 82.3 | 4.7 | 8.4 | 12.3 |

| Cacao husk - San Martín Province | 43.8 | 5.2 | 19.5 | 11.9 | 19.7 | 24.5 |

| Cacao husk - Mariscal Cáceres Province | 37.6 | 11.6 | 16.8 | 10.5 | 23.5 | 21.6 |

| Rice husk - San Martín Province | 11.9 | 18.9 | 19.5 | 5.7 | 44.1 | 4.6 |

| Rice husk - Bellavista Province | 9.7 | 15.3 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 68.0 | 3.16 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) - Bellavista Province | 1.4 | 12.4 | 79.5 | 0.4 | 6.4 | 11.9 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) - Rioja Province | 0.9 | 4.1 | 78.8 | 5.2 | 11.1 | 11.3 |

| Split rice (< 1/4 grain size) - San Martín Province | 3.4 | 6.7 | 83.3 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 13.3 |

| Rice polishing - Bellavista Province | 17.5 | 0.2 | 66.9 | 10.5 | 4.9 | 19.1 |

| Rice polishing - Rioja Province | 19.0 | 5.5 | 52.6 | 15.7 | 7.1 | 18.3 |

| Rice polishing - San Martín Province | 19.5 | 7.6 | 55.8 | 9.7 | 7.4 | 17.9 |

| Coconut cake - Picota Province | 8.0 | 1.9 | 20.8 | 52.8 | 16.5 | 24.9 |

ConventionsA: Non-protein nitrogen; B1: Rapidly degradable true protein; B2: Intermediate degradable true protein; B3: Slowly degradable true protein; C: Non-degradable protein

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Those inputs considered as protein, such as cacao husk and coconut cake, showed different percentages of protein fractions. As indicated above, the cacao husk contains a higher fraction A value than the other inputs, but it also had a considerable percentage of fraction B (between 36.5 % and 38.9 %), with the B2 fraction showing the highest concentration (between 16.8 % and 19.5 %). This fraction is normally fermented slowly in the rumen due to the bacteria that require ammonia as the sole source of nitrogen (Russell, O'Connor, Fox, Van Soest, & Sniffen, 1992). Fraction C of this input ranged between 19.7 % and 23.5 %.

On the other hand, the coconut cake showed a higher amount of protein fraction B (75.5 %), where the slowly degradable true protein (B3) showed a higher value (52.8 %). The B3 fraction, since it only degrades in the rumen by 10.0-25.0 % and the rest passes into the intestinal tract, is the fraction with the highest use efficiency in ruminants (Sniffen et al., 1992). Fraction C of the coconut cake had a value of 16.5 %. Of these protein inputs, the coconut cake would become more efficient due to the high content of fraction B3 compared to cacao husk, and as it has a lower fraction A (8.0 %) and fraction C (16.5 %), it is considered a good quality protein input. In this regard, Guevara-Mesa et al. (2011) reported that coconut flour presented fractional values A, B1, B2, B3, and C of 11.41 %, 3.15 %, 23.26 %, 48.02 %, and 14.17 %, respectively, i.e., similar values to those observed in the current study.

Several works indicate the fractioning of protein from different inputs and forages for ruminant feeding such as alfalfa, corn, soybean flour, wheat bran, cotton, sorghum, barley, oat, cropping residues, leguminous and grass forages (Gaviria, Rivera & Barahona, 2015; Guevara-Mesa et al., 2011; Sniffen et al., 1992). However, it is still necessary to investigate in detail, information on the fractioning of proteins in non-traditional inputs and, with greater emphasis on agroindustrial residues from the tropics in Peru. Likewise, Agroindustrial residues considered as protein show similar usable crude protein uCP values (cacao husk between 21.6 % and 24.5 %, and coconut cake with 24.9 %) (table 3).

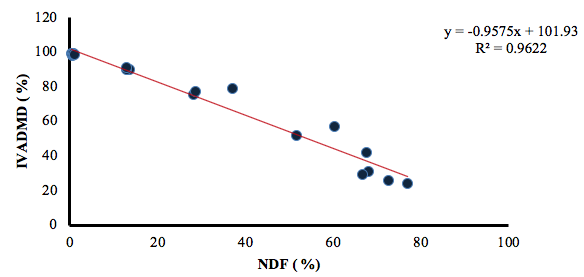

The relationship between neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and the in vitro dry matter digestibility (IVADMD) of the agroindustrial residues evaluated can be observed in figure 1.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Figure 1 Relationship between the neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and the in vitro apparent dry matter digestibility (IVADMD) of the agroindustrial residues in the San Martín region, Peru.

A significant negative correlation was found between both parameters (r = -0.98), i.e., when there was an increase in the NDF, the IVADMD value decreased. This relationship was most notable in those residues with high NDF content, such as rice husk, palm fiber, heart of palm husk and palm kernel cake, since the in vitro digestibility of the NDF would be reduced and, therefore, also the dry matter digestibility (Mertens, 2009). Mahyuddin (2008) reported a negative correlation between NDF and IVADMD of tropical pastures; however, the coefficient of determination of this work (R2= 0.24) was lower compared to the results of the current study (R2= 0.96). The reason could be the variation between the chemical components among tropical forage species, while, in the current work, agroindustrial residues had less variation in these components. Another study also reported a negative relationship between the IVADMD and the NDF of Kikuyu grass, showing an R2 value of 0.75, that is, a lower value compared to what was found in other local residues of the tropics (Rodríguez, 1999). On the other hand, those residues with low levels of NDF and high values of IVADMD, such as coconut cake, coffee pulp, cacao husk, rice dust, split rice with < 1/4 grain size and split rice with > 1/4 grain size, would be residues with higher use.

Conclusions

Agroindustrial residues with increased energy potential and with good in vitro digestibility (IVADMD) were split rice with < 1/4 grain size, rice dust and split rice with > 1/4 grain size, with net energy of lactation (NEL) values of 2.1 ± 0.02, 2.1 ± 0, 02 and 1.7 ± 0.02 Mcal/kg on a dry basis, respectively, and IVADMD values of 99.3 ± 0.2 5 %, 90.5 ± 0.4 2 % and 99.0 ± 0.68 %, respectively.

The agroindustrial residues with the best protein potential were cacao husk and coconut cake, with crude protein levels of 21.8 ± 1.34 % and 21.9 %, respectively. Agroindustrial residues with fibrous potential were rice husk, palm fiber and heart of palm husk with neutral detergent fiber (NDF) values of 69.8 ± 4.17 %, 72.6 ± 6.45 %, and 60.4 %, respectively. However, only the heart of palm husk reported a regular IVADMD value (57.2 %).

Agroindustrial residues from the region of San Martín, Peru, have varied energy and protein use potential and would be useful in cattle feeding in the tropics.

Acknowledgments

All the authors wish to thank doctor Uta Dickhoefer for her valuable help in carrying out the protein fractioning chemical analysis in the Laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences in the Tropics, Hohenheim University, Germany. Likewise, to Programa Nacional de Innovación Agraria (PNIA) for financing the execution of this study, which is part of the Project “Strategic nutritional supplementation for bovine cattle in the San Martín and Amazonas regions through the use of multi-nutritional blocks and local residues as an adaptation strategy to the impact of climate change (Contract No. 016-2016 INIA-PNIA-IE).

REFERENCES

Alemán, A. (2012). Evaluación de la esterificación sobre cascarilla de arroz como estrategia para incrementar la capacidad de remoción del colorante rojo básico 46 [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia]. http://bdigital.unal.edu.co/6861/1/15679816_2012.pdf [ Links ]

Ankom. (2017a). Neutral detergent fiber in feeds - filter bag technique (for A2000 and A2000I).https://www.ankom.com/sites/default/files/document-files/Method_13_NDF_A2000.pdf [ Links ]

Ankom. (2017b). In vitro true digestibility method (IVTD - Daisy).https://www.ankom.com/sites/default/files/document-files/Method_3_Invitro_D200_D200I.pdf [ Links ]

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). (2005). Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (18th Edition). [ Links ]

Bochi-Brum, O., Carro, D., Valdés, C., González, J., & López, S (1999). Digestibilidad in vitro de forrajes y concentrados: efecto de la ración de los animales donantes de líquido ruminal. Archivos de Zootecnia, 48(181), 51-61. [ Links ]

Cardona, M., Sorza, J., Posada, S., & Carmona, J. (2002). Establecimiento de una base de datos para la elaboración de tablas de contenido nutricional de alimentos para animales. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias, 15(2), 240-246. [ Links ]

Crampton, E., & Harris, L. E. (1974). Nutrición animal aplicada. Editorial Acribia. [ Links ]

Cuesta, A., Conde, A., & Moreno, M. L. (2000). Tratamiento y calidad nutritiva de subproductos fibrosos de palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Revista Palmas, 21(especial), 264-274. https://publicaciones.fedepalma.org/index.php/palmas/article/view/794/794 [ Links ]

Ensminger, M. E. (1992). The stockman´s handbook. Interstate Publishers Inc. Ill. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (1997). Parte III: La agroindustria y el desarrollo económico. http://www.fao.org/docrep/w5800s/w5800s12.htm [ Links ]

Fundación Española para el Desarrollo de la Nutrición Animal (FEDNA). (2015). Tabla de la composición química de la torta de palmiste. http://www.fundacionfedna.org/node/439 [ Links ]

Fundación Española para el Desarrollo de la Nutrición Animal (FEDNA). (2016a). Tabla de la composición química del salvado de arroz desengrasado. http://www.fundacionfedna.org/ingredientes_para_piensos/salvado-de-arroz-desengrasado [ Links ]

Fundación Española para el Desarrollo de la Nutrición Animal (FEDNA). (2016b). Tabla de la composición química de la torta de presión de copra.http://www.fundacionfedna.org/ingredientes_para_piensos/torta-de-presi%C3%B3n-de-copra [ Links ]

Gaviria, X., Rivera, J., & Barahona, R. (2015). Calidad nutricional y fraccionamiento de carbohidratos y proteína en los componentes forrajeros de un sistema silvopastoril intensivo. Pastos y Forrajes, 38(2), 194-201. [ Links ]

Giraldo, L. A., Gutiérrez, L. A., & Rúa, C. (2007). Comparación de dos técnicas: in vitro e in situ para estimar la digestibilidad verdadera en varios forrajes tropicales. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias, 20(3), 269-279. [ Links ]

Goering, H. U., & Van Soest, P. J. (1970). Forage fiber analyses (apparatus, reagents, procedures, and some applications) (No. 379). US Agricultural Research Service, Department of Agriculture. [ Links ]

Guevara-Mesa, A. L., Miranda-Romero, L., A., Ramírez-Bribiesca, J. E., González-Muñoz, S. S., Crosby-Galván, M. M., Hernández-Calva, L. M., & Del Razo-Rodríguez, O. E. (2011). Fracciones de proteína y fermentación in vitro de ingredientes proteínicos para rumiantes. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 14(2), 421-429. [ Links ]

Holdridge, L. (1987). Ecología basada en zonas de vida. Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA). [ Links ]

Lecumberri, E., Mateos, R., Izquierdo, M., Rupélez, & P., Goya, L. (2007). Dietary fiber composition, antioxidant capacity and physico-chemical properties of a fiber-rich product from cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.). Food Chemistry, 104(3), 948-954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.054 [ Links ]

Licitra, G., Hernandez, T. M., & Van Soest, P. J. (1996). Standardization of procedures for nitrogen fractionation of ruminant feeds. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 57(4), 347-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8401(95)00837-3 [ Links ]

Mahyuddin, P. (2008). Relationship between chemical component and in vitro digestibility of tropical grasses. Hayati Journal of Biosciences, 15(2), 85-89. https://doi.org/10.4308/hjb.15.2.85 [ Links ]

McDonald, P., Edwards, R. A., & Greenhalgh, J. F. D. (1981). Animal nutrition (3. ed.). Longman. [ Links ]

Mertens, D. R. (2009). Impact of ndf content and digestibility on dairy cow performance. wcds Advances in Dairy Technology, 21, 191-201. [ Links ]

Mirzaei-Aghsaghali, A., & Maheri-Sis, N. (2008). Nutritive value of some agro-industrial by-products for ruminants - A review. World Journal of Zoology, 3(2), 40-46. [ Links ]

Mosquera, P., Martínez, G., Medina, H., & Hinestroza, L. (2013). Caracterización bromatológica de especies y subproductos vegetales en el trópico húmedo de Colombia. Acta Agronómica, 62(4), 326-332. https://doi.org/10.15446/acag [ Links ]

Mugerwa, S., Kabirizi, J., Zziwa, E., & Lukwago, G. (2012). Utilization of crop residues and agro-industrial by-products in livestock feeds and feeding systems of Uganda. International Journal of Biosciences (IJB), 2(4), 82-89. [ Links ]

National Research Council (NRC). (1989). Nutrient requirements of dairy cattle (6. ed.) The National Academies Press. [ Links ]

Pandey, A., Soccol, C., Nigam, P., Brand, D., Mohan, R., & Roussos, S. (2000). Biotechnological potential of coffee pulp and coffee husk for bioprocesses. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 6(2), 153-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-703X(00)00084-X [ Links ]

Posada, O. S., Rosero, N. R., Rodríguez, N., & Costa, C. A. (2012). Comparación de métodos para la determinación del valor energético de alimentos para rumiantes. Revista MVZ Córdoba, 17(3), 3184-3192. https://doi.org/10.21897/rmvz.219 [ Links ]

Preston, T. R., & Leng, R. A. (1987). Matching ruminant production systems with available Resources in the tropics and sub-tropics. Penambul Books. [ Links ]

Reyes, J. (1991). Composición de insumos no tradicionales usados en la alimentación animal en la provincia de Piura. Universidad Nacional de Piura. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, D. (1999). Caracterización de la respuesta a la fertilización en producción y calidad forrajera en los valles de Chiquinquirá y Simijaca (Estudio del caso) [Tesis de pregrado]. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

Rosas, D., Ortiz, H., Herrera, J., & Leyva, O. (2016). Revalorización de algunos residuos agroindustriales y su potencial de aplicación a suelos agrícolas. Agroproductividad, 9(8), 18-23. [ Links ]

Russell, J. B., O’Connor, J. D., Fox, D. G., Van Soest, P. J., & Sniffen, C. J. (1992). A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluation cattle diets: I ruminal fermentation. Journal of Animal Science, 70(11), 3551-3561. https://doi.org/10.2527/1992.70113551x [ Links ]

Saval, S. (2012). Aprovechamiento de residuos agroindustriales: pasado, presente y futuro. Revista de la Sociedad Mexicana de Biotecnología y Bioingeniería A.C.,16(2), 14-46. https://smbb.mx/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Revista_2012_V16_n2.pdf [ Links ]

Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e hidrología del Perú (Senamhi). (2018). Boletín Climático Nacional junio 2018. https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/load/file/02215SENA-60.pdf [ Links ]

Shimada, A. (2009). Nutrición Animal. Editorial Trillas. [ Links ]

Sniffen, C. J., O´Connor, J. D., Van Soest, P. J., Fox, D. G., & Russell, J. B. (1992). A Net Carbohydrate and Protein System for Evaluating Cattle Diets: II. Carbohydrate and Protein Availability. Journal of Animal Science, 70(11), 3562-3577. https://doi.org/10.2527/1992.70113562x [ Links ]

Soto, M. J. (2012). Desarrollo del proceso de producción de cascarilla de semilla de cacao en polvo destinada al consumo humano [Tesis de pregrado]. Universidad Simón Bolívar. [ Links ]

Tham, H. T., Man, N. V., & Preston, T. R. (2008). Estimates of protein fractions of various heat-treated feeds in ruminant production. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 20.http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd20/supplement/tham2.htm [ Links ]

Tingshuang, G., Sánchez, M. D., & Yu, G. P. (2002). Composition, nutritive value and upgrading of crop residues. Animal Production Based on Crop Residues - Chinese Experiences. http://www.fao.org/3/y1936e/y1936e00.htm [ Links ]

Waller, J. C. (2004). Byproducts and unusual feedstuffs. The Feedstuffs Reference Issue & Buyers Guide, 83(38), 18. [ Links ]

Zhao, G. Y., & Cao, J. E. (2004). Relationship between the in vitro-estimated utilizable crude protein and the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System crude protein fractions in feeds for ruminants. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 88(7-8), 301-310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0396.2004.00485.x [ Links ]

Received: March 19, 2019; Accepted: November 05, 2019

texto en

texto en