Introduction

One of the most recurrent phenomena in rural areas worldwide is population aging. By 2030, the population aged 65 and above will increase (Latin America 71 %), with social, economic, and cultural implications (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2017a)). For agricultural activities (in particular) and rural areas (in general), population aging implies not only reduced labor force but also the challenge of engaging young people in production activities (FAO, 2014). The importance of youth engagement in rural activities lies in the role they can play in the future of the rural economy. For example, they can increase productivity by innovating or integrating modern agriculture into traditional farming (older farmers are less likely to adopt new technologies) (FAO, 2014, 2017b).

Regarding literature, although rural development institutions (e.g., FAO and Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural [RIMISP]) have recommended that initiatives focused on the empowerment of the rural youth in Latin America be researched, designed, or evaluated, few researchers have analyzed the level of knowledge reached in this topic. Kessler (2006) reviewed literature in which approaches such as rural youth identity, family and gender relations, educational problems, working world, social and political participation, migrations, and native issues were discussed. This author defined the review as a “first mark of gaps” (Kessler, 2006). Moreover, Guiskin (2019) reviewed the main findings of Latin American rural youth between 2008 and 2018. Elements such as demographic dynamics, socioeconomic characterizations, priority groups, and topics of interest were described and discussed.

As a common element, the authors of these two documents reviewed, discussed, and presented research approaches to Latin American rurality (e.g., education, migration, work). Nonetheless, information such as methods and participants were not reported. Both cases suggested increasing the knowledge of rural youth in Latin America.

This paper aims to fill this gap by presenting a systematic literature review. As an innovative element, this qualitative review focuses not only on research approaches but also on how researchers have conducted studies about this issue (e.g., participants, methods, and main findings). It presents the description, analysis, and discussion of 45 articles published in peer-reviewed journals during 2001- 2019.

Materials and methods

Articles published in peer-reviewed journals during 2001-2019 served as the data source. They were searched using the Purdue University online library, Google Scholar, Scopus, and the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). These datasets were chosen based on the accessibility to download the articles for analysis (i.e., there were no monetary costs for using these datasets). Moreover, these sources ensured a broader range of authors and articles (in comparison to using only one dataset). The following keywords (in English, Spanish, and Portuguese) were used: rural-youth, rural-youth-initiatives, Latin-America-and-Caribbean, youth-expectations, youth-motivations, and rural-youthmigration. Criteria for selecting papers were: 1) published in an indexed journal, 2) approved after a peer-review process, 3) addressed an issue about rural youth of Latin America, and 4) published during 2001-2019.

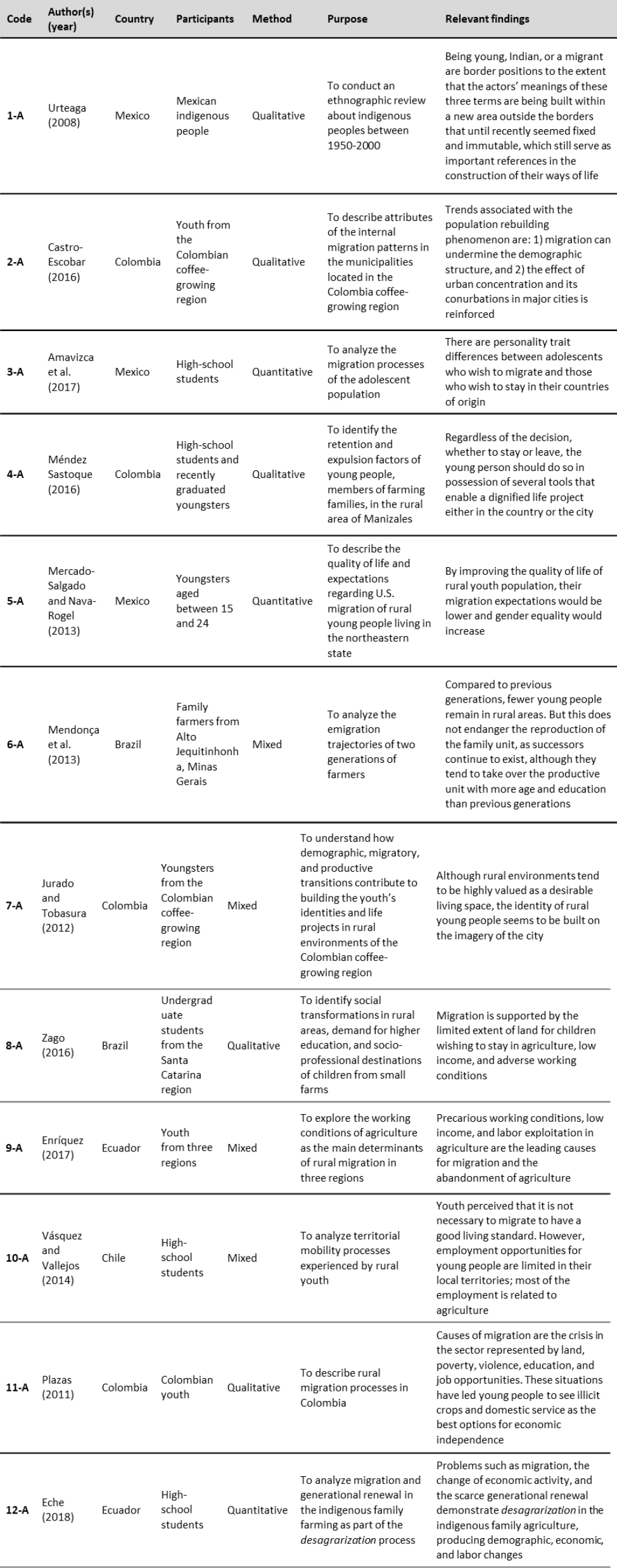

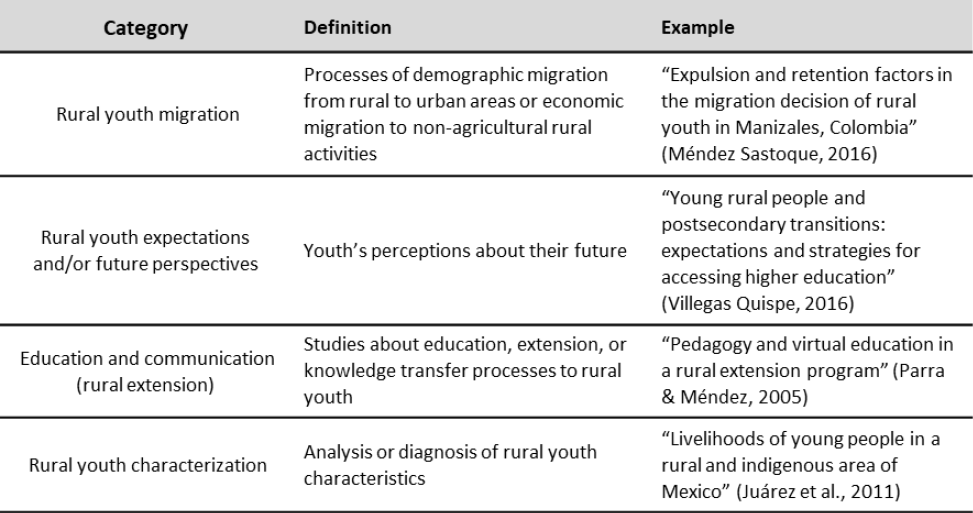

Once papers were selected, variables such as year of publication, participants (i.e., human subjects), objectives, methods, results, conclusions, and keywords were analyzed and organized into a data matrix (Excel file). Based on it, and following an inductive approach, articles were manually coded (by one researcher) and categorized into four groups (table 1). A unique category was assigned to each paper.

Table 1. Definition of categories (approaches) addressed by articles

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Approaches were coded to facilitate the reading of results and tables: (migration = A; expectations = B; education and communication = C; characterizations = D). For each group (table 1), an analysis was conducted based on methods (i.e., articles were divided into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method), objectives, participants, results, findings, and implications. Definitions were used to perform the analysis on those papers that followed qualitative approaches, as follows:

1) Narrative research: “Understood as a spoken or written text giving an account of an event/action or series of events/actions, chronologically connected.” (Creswell, 2007, p. 53).

2) Phenomenology: “Describes the meaning for several individuals of their lived experiences of a concept or a phenomenon, focusing on describing what all participants have in common as they experience a phenomenon” (Creswell, 2007, p. 57).

3) Grounded theory: “The intent of this kind of study is to move beyond description and to generate or discover a theory, an abstract analytical schema of a process” (Creswell, 2007, p. 62).

4) Ethnography: “… is a design in which the researcher (based on observations) describes and interprets the shared and learned patterns of values, behaviors, beliefs, and language of a culture-sharing group” (Creswell, 2007, p. 68).

5) Case study: “… involves the study of an issue explored through one or more cases within a bounded system” (Creswell, 2007, p. 73).

Results and discussion

After conducting the search, 45 articles from 13 Latin America and the Caribbean countries, published between 2001 to 2019, met the selection criteria. The studies were conducted in the following contexts: Argentina (2), Bolivia (1), Brazil (14), Chile (2), Colombia (12), Costa Rica (1), Cuba (2), Ecuador (3), Mexico (7), Peru (2), Venezuela (2), the Caribbean (1), and Latin America at large (1). According to the content and objectives in the articles, they were grouped into four categories: 1) 12 rural youth migration, 2) 15 as education and/or communication (rural extension), 3) 13 as expectations or futures perspectives, and 4) five as rural youth characterization. The results are presented by category, purpose, location (generalizability), method, participant, and relevant finding.

Rural youth migration approach

Locations and perspectives

Twelve research studies focused on youth migration (from economic and sociology disciplines) were conducted in Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Chile (table 2). The perspectives of migration addressed were rural-urban migration (6-A; 7-A; 8-A; 10-A), international migration (Mexico to the United States) (3-A; 5-A), and internal migration among rural areas (2-A; 9-A; 12-A). Some papers combine more than one perspective (1-A; 4-A;11-A).

Methods

These studies performed qualitative (1-A; 2-A; 4-A; 8A), quantitative (3-A; 5A; 12A), and mixedmethod analyses (6-A; 7-A; 9-A; 10-A). Based on Creswell’s (2007) definition or division of qualitative approaches, a case study was conducted in the document coded as 4-A. The three other qualitative analyses (1-A; 2-A; 8-A) were descriptive, whose method of inquiry did not match Creswell’s categories. Concerning the mixed-method analysis, concurrent designs were employed in three studies (6-A; 7-A; 9-A) and a sequential design (quantitative-qualitative) in one document (10-A). Even though these four articles presented and discussed both qualitative and qualitative data, they lacked data triangulation (i.e., how qualitative and quantitative data were integrated to understand or explain the issue).

Participants

Differences in the criterion to select participants were observed (e.g., age, education level, or participation in any specific activity such as agriculture). Five research studies focused on education level; four collected data from high-school students (3-A; 4-A; 10-A; 12-A) and one from undergraduate students (8-A). Moreover, two other papers used the criterion of age; one selected participants aged 12-25 (6-A) and the other young people aged 14-25 (5-A). Finally, five papers presented neither age limitation nor education level to select the participants. These papers discussed rural youth migration from a general perspective (1-A; 2-A; 7-A; 9-A; 11-A).

Generalizability

Concerning the geographic implications of these research studies, two articles were country-oriented. The study coded as 11-A presented a general discussion about rural youth migration in Colombia, while 1-A discussed the same issue for Mexico. The other ten research studies were territorially oriented, in which data collection took place in one specific region (e.g., municipality, province, or department).

Principal findings

Most of the authors coincide on the fact that the rural youth migration process occurs due to a lack of agricultural production factors (e.g., capital, land, and labor) (3-A; 4-A; 6-A; 9-A; 10-A; 11-A; 12- A). These researchers emphasized that agriculture (the main economic activity in rural areas) does not provide enough income for youth to increase their living standards. Thus, the decision to live in rural areas could result in poverty and marginalization. Another research study concluded that an important factor promoting youth migration from rural areas was searching for educational opportunities (8-A); due to the low offer of higher education in rural areas, youth migrate to urban areas. In addition, some authors highlighted that migration is an expected effect of demographic transitions (2-A; 7-A), in which youth’s identity seems to be built on the imaginary of urban areas. This demographic change can have different effects depending on characteristics such as gender or ethnicity. For instance, for ethnic rural populations, the migration process implies creating urban ethnic settlements, which could be defined as ethnicities of displacement (1-A).

Education and/or communication

Locations and perspectives

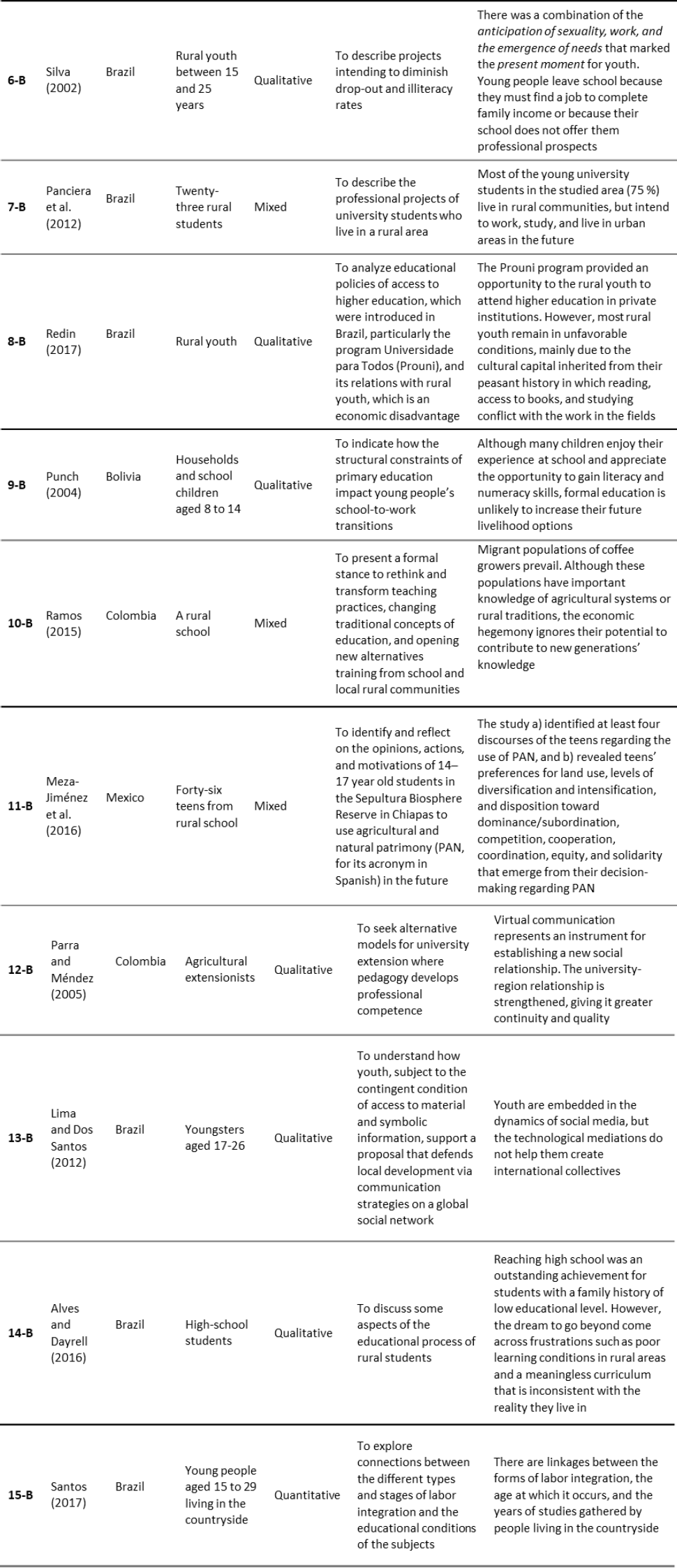

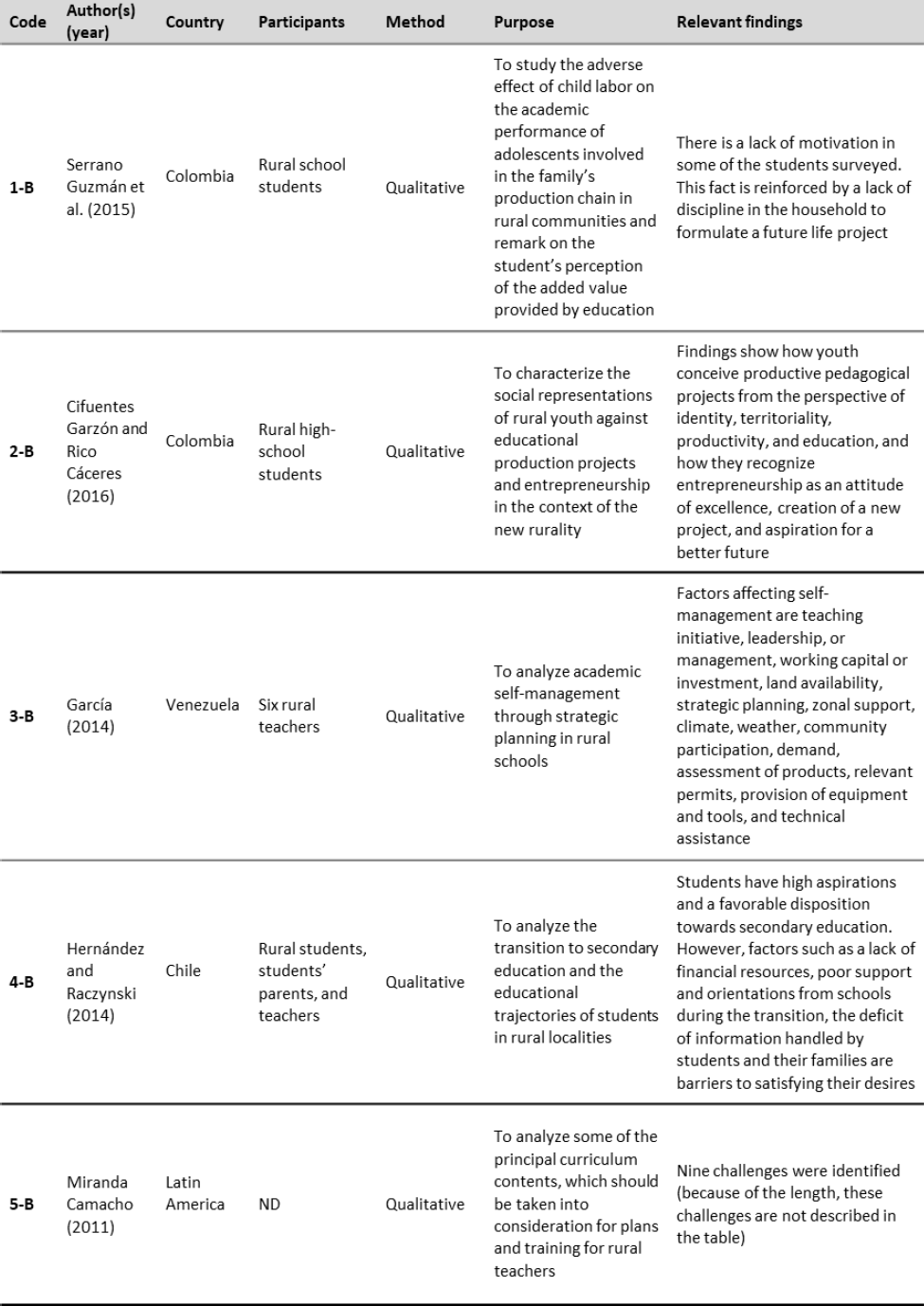

Fifteen articles about formal and/or non-formal education, communication, and/or extension processes were identified (table 3). These studies were conducted in Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, Brazil, Bolivia, and Chile. An additional research study focused on Latin-American youth (in general). Regarding the general purpose of these studies, the main topics were relationship between work and education (or their impact) (1-B; 9-B; 15-B), school projects for rural students (entrepreneurship) (2- B; 7-B), students’ or teachers’ traits, such as self-management, motivation, or aspirations (3-B; 11-B), general discussions or analysis about rural education policies (5-B; 8-B), students’ barriers to their future (4-B; 6-B; 14-B), virtual education and social media (12-B; 13-B), and rethinking education concepts for a new rurality (i.e., switching traditional education concepts for alternative training from school and local rural communities) (10-B).

Methods

Eleven out of 15 articles employed qualitative analysis (1-B; 2-B; 3-B; 4-B; 5-B; 6-B; 8-B; 9-B; 12-B; 13-B; 14-B). Based on Creswell’s division, six studies were case studies (1-B; 4-B; 6-B; 9-B; 12-B; 13- B), two were ethnographic research (2-B; 14-B), and one was a phenomenological study (3-B). Those that reported ethnography as a methodological approach conducted participant interviews; this suggests that these research studies were not aligned with Jones et al. (2013) recommendations for this kind of qualitative approach.

Regarding other qualitative approaches, the research coded 6-B addressed a hermeneutic critique (Simpson, 2021) about the new rurality and education in Latin America. Study 8-B was a general qualitative descriptive analysis of access to higher education policies for rural students in Brazil. The article coded as 11-B carried out a qualitative analysis to evaluate attitudes, motivations, and decisions of contemporary rural young smallholders (this study played a simulation game to collect data). The studies that followed mixed-method analysis (7-B, 10-B, and 11- B) did not report either the type of design (e.g., concurrent or sequential) or qualitative and qualitative data triangulation. Finally, one document (15-B) made a quantitative analysis using descriptive statistics.

Participants

Depending on the purpose of each research, participants were selected based on different criteria. Papers coded as 1-B, 2-B, 7-B, 10-B, 11-B, and 14- B only studied rural school students. In contrast, research study 3-B collected data from rural school teachers. In contrast, some other papers included more than one kind of participant. For example, research studies 4-B, 9-B, and 10-B included not only students, but also households and/or school teachers for collecting data. On the other hand, research studies 6-B, 8-B, 13-B, and 15-B used age as a criterion; these papers did not limit the participants’ selection to any education institution.

Table 3. Main components of the articles focused on education and/or communication

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Principal findings

Studies that focused on the relationships between work and education (or their impact) concluded that there could be discouragement and a lack of motivation among rural youth because the absence of family discipline prevents them from formulating a future life project (1-B). In addition, although many children enjoy and appreciate their experience at school, formal education is unlikely to increase their future livelihood options (9-B). Other results suggest a positive correlation between the forms of labor integration and the years of studies gathered by rural youth (15-B).

Research studies focused on school projects for rural students (i.e., entrepreneurship) concluded that rural youth perceive them as an aspiration for a better future (2-B). Regarding their life project and future, although they are rural youth, their projects are more focused on urban activities (7-B).

Regarding those documents centered on students’ or teachers’ traits (i.e., self-management, motivation, or aspirations), it was identified that educational socio-environmental games are tools that promote students’ and teacher’s motivations toward agricultural and natural patrimony topics (11-B). Moreover, teaching initiative, leadership or management, working capital or investment, land availability, and strategic planning were associated with rural teachers’ self-management (3-B). In the same way, papers related to virtual education and social media concluded that rural youth are embedded in social media (13-B), and these tools represent an instrument for establishing a new social relationship (12-B).

Those studies about rural students’ barriers found that factors such as low family income or poverty (4-B; 6-B), poor support from their schools (4-B), or low quality or decontextualized education (4-B; 6-B; 14-B) do not allow them to accomplish their goals or dreams. Finally, the paper focused on rethinking education concepts for the new rurality (10-B) concluded that school achievement indicators with agricultural empowerment promote interdisciplinary activities for rural students, helping them to understand local issues from different perspectives.

Rural youth’s expectations or prospects

Locations and perspectives

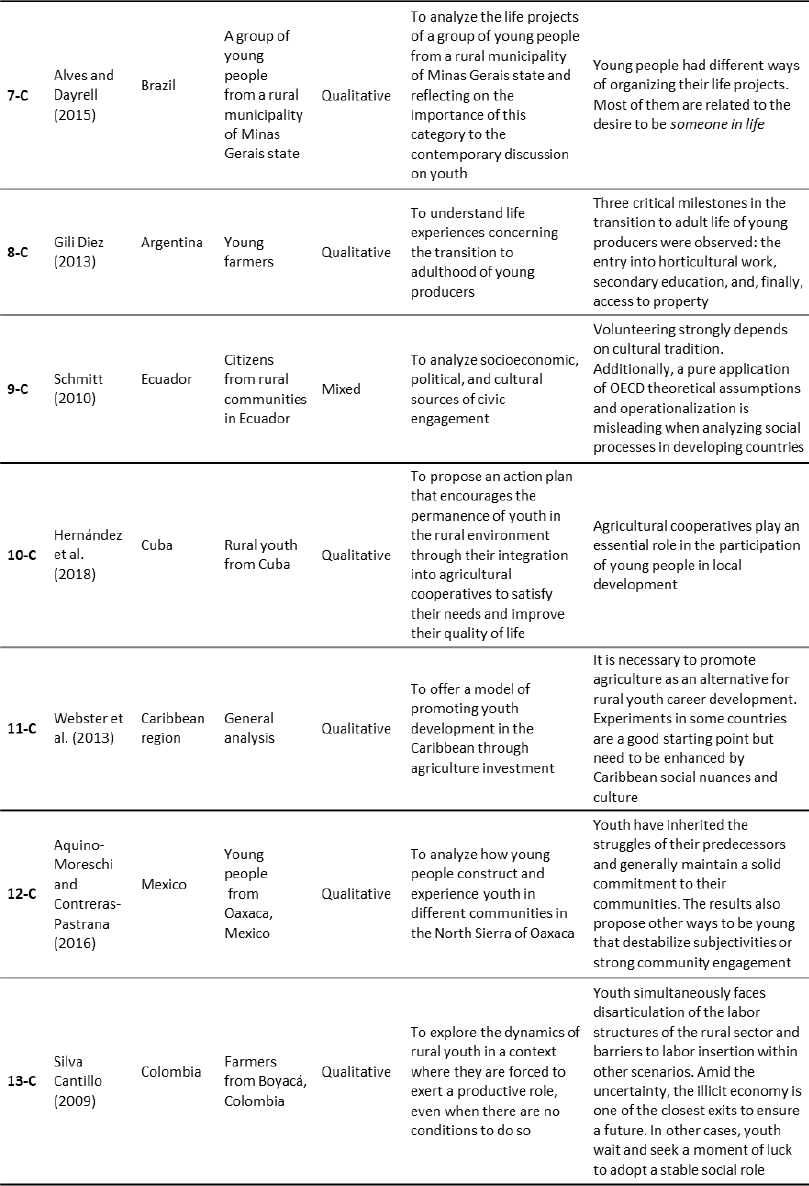

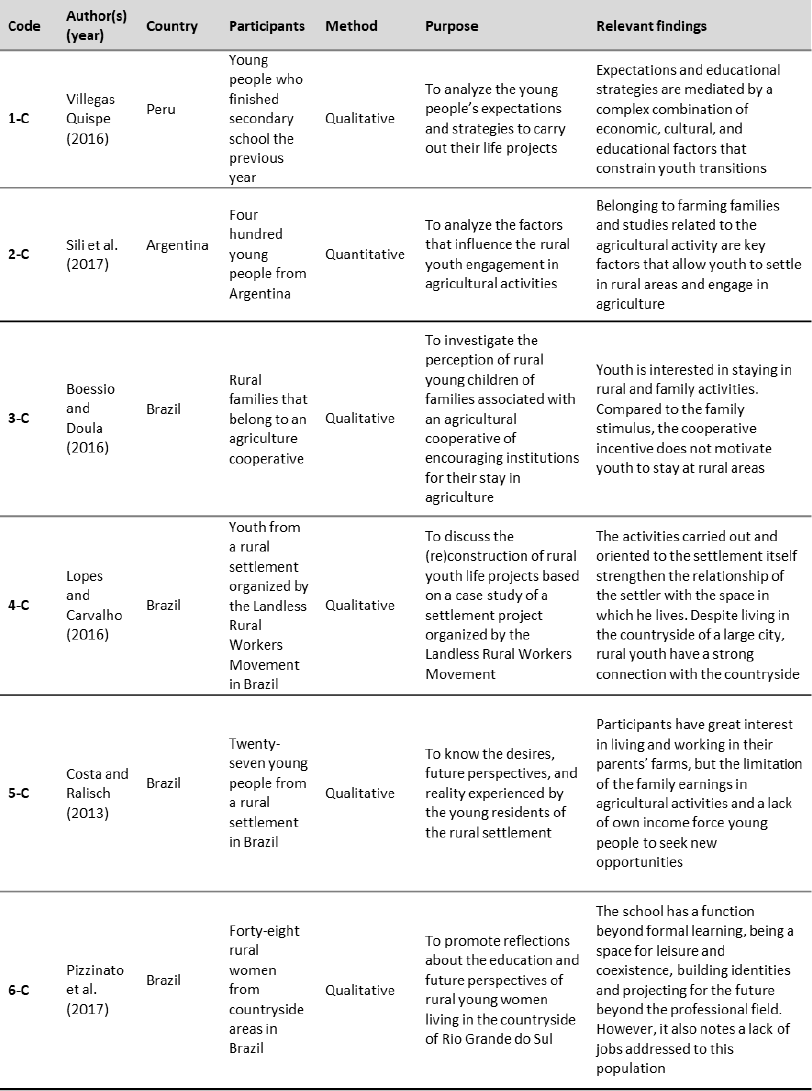

Thirteen articles related to rural youth perspectives or expectations were identified (table 4). These articles addressed this topic from three sub-categories: 1) general factors related to rural youth’s expectations and perspectives (1-C, 5-C, 6-C, 7-C, 9-C, 12-C); 2) the relation between agriculture activities or initiatives and the rural youth’s perspectives (i.e., how participants perceive agricultural activities as a career alternative for their future) (2-C, 3-C, 4-C, 8-C, 10-C, 13-C); and, 3) factors related to rural youth’s civic engagement (i.e., how participants are actively involved in social activities that concern their communities) (9-C). Research studies were conducted in Peru, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico. The document coded as 11-C provided a general discussion about the Caribbean rural youth.

Methods

Eleven articles involved a qualitative analysis. Three studies reported ethnographic elements during data collection (e.g., observations or interactions) (1-C; 10-C; 12-C). Two studies (10-C and 12-C) mentioned (explicitly) a combination between ethnography elements and other methodological approaches (e.g., interviews). In contrast, study 1-C defined its method as ethnography; however, it reported data collection or analysis interviews. As discussed before, it could be suggested that this was not an ethnographic study, as defined by Creswell (2007) and Jones et al. (2013). Based on Creswell’s categories for qualitative analysis, cases studies analyses were conducted in two research studies (3-C; 4-C) and a grounded theory in one (6-C). Finally, five documents carried out a general qualitative analysis.

Regarding quantitative analysis, one document (2-C) conducted logistic regressions to analyze general factors concerning rural youth development; it collected data from a random sample (N = 400). Among all studies discussed in our paper, this is the second study that used probabilistic sampling. Compared to other strategies, this kind of sampling allows researchers to generalize results and identify sociodemographic differences (Bornstein et al., 2013). Finally, another research study was a mixed-method analysis (9-C). Just as other mixed-method research discussed before, the authors did not mention the type of design or how qualitative and quantitative data was triangulated.

Participants

Along with the condition of being rural youth (12-29 years old), some studies used other criteria to define participants. Three studies were conducted with families belonging to rural settlements or cooperatives (3-C; 4-C; 5-C). Two other research studies focused on young farmers (8-C; 13-C). Moreover, study 6-C defined participants based on gender (only females were included in the study). Of all the papers included in our analysis, this is the only document focused on rural youth females. According to Díaz and Fernández (2017), given the gap of opportunities and barriers between young males and females in Latin America, it is necessary to investigate this issue. Finally, a research study (1-C) was conducted with rural youth who finished secondary school a year before the study.

Generalizability

According to the scope of each study, research results can be generalized at three levels. First, study 11-C had a regional-continental analysis, in which discussion or findings are oriented toward Latin American policies. Second, research studies 2-C and 9-C have analysis and discussions with national orientation (i.e., Argentina and Ecuador, respectively). Finally, other studies were oriented toward youth in a specific local community (e.g., province, settlement, municipality).

Principal findings

In general terms, research studies that focused on rural youth’s expectations concluded that there are multiple desires in youth’s life. Thus, projects are planned in different ways to be someone (7-C). In some situations, these projects implied the destabilization of traditional subjectivities or practices established in their communities (e.g., agricultural activities) (12-C). Regarding the relation between schools and youth’s expectations or perspectives, institutions play an essential role in awakening vocational interests (beyond formal learning) (6-C). However, youth face economic, cultural, and educational constraints (1-C; 6-C). They are commonly marginalized in work structures (13-C). Regarding family influences, there is a strong relationship between them and youth’s expectations. Thus, rural young people are willing to continue their family activities (e.g., agriculture) (3-C; 4-C; 5- C). Despite this desire, limited job opportunities or low-income force youth to leave their family property or their original plan (5-C). Concerning the relation between agricultural initiatives or programs and youth’s perspectives, belonging to cooperatives, settlements, or families of farmers increases the willingness of rural youth to pursue agricultural activities in the future (2-C; 8-C; 10-C).

Table 4. Main components of the articles focused on expectations or futures perspectives

Source: Elaborated by the authors

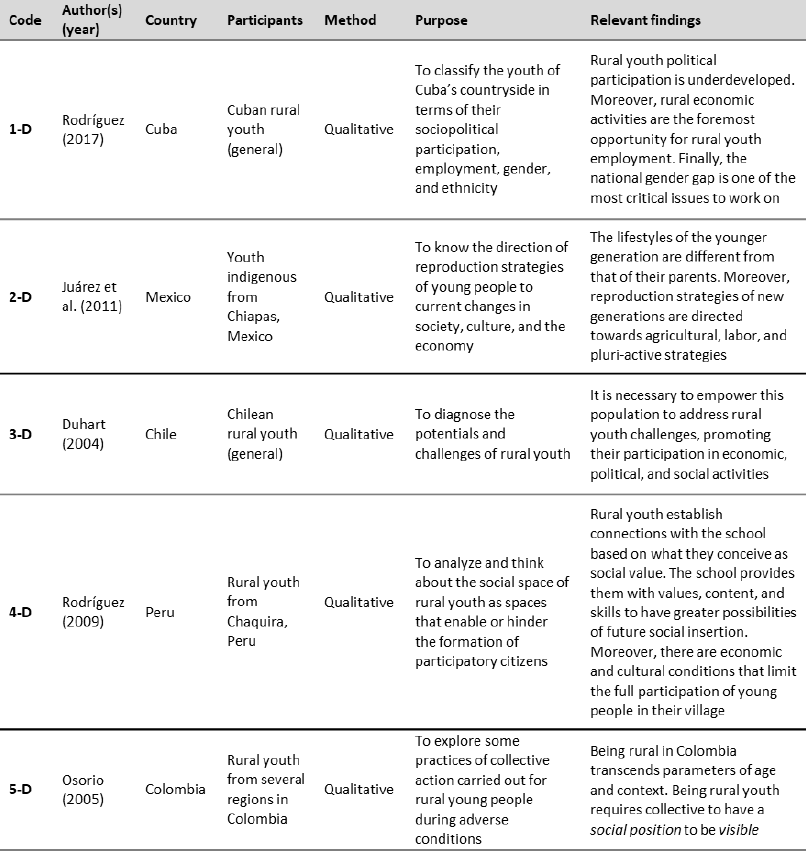

Characterization or diagnosis of rural youth

Locations and perspectives

Five research studies related to the diagnosis or the analysis of rural youth characteristics were found (table 5). These studies were conducted in Cuba (1-D), Mexico (2-D), Chile (3-D), Peru (4-D), and Colombia (5-D). The main topics addressed by these studies were: 1. Rural youth socio-political, economic, and ethnicity identity (1-D and 4-D) and 2. Diagnosis of rural youth challenges and potentials (2-D, 3-D). The document coded as 5-D addressed both perspectives.

Methods

All studies were qualitative analyses. Two of them reported approaches that match with those reported by Creswell (2007). The study coded as 2-D followed a case study, in which the “case” was made up by rural youth indigenous from a community in Chiapas, Mexico. Moreover, the study coded as 4-D reported an ethnography as an approach to inquiry; however, because interviews were developed to collect data, its method could match with a different approach, as suggested by Creswell (2007). Concerning the studies coded as 1-D, 3-D, and 5-D, descriptive qualitative analyses were followed.

Participants

Studies coded as 1-D, 3-D, and 5-D addressed a comprehensive national analysis for Cuban, Colombian, and Chilean rural youth, respectively; therefore, no primary data was collected. On the other hand, the two other studies supported their analysis on data collected from rural youth, as follows: 1) The study coded as 2-D collected data from rural Mexican youth indigenous (not reporting the total number of participants) and 2) the study coded as 4-D along with the ethnographic analysis conducted in a rural community in Peru collected individual data from 18 rural youth.

Principal findings

Regarding studies focused on the rural youth identity, authors concluded that the concept of “rural youth” goes beyond a definition based on age and context and is closely related to youth participation in economic, political, and social activities in rural contexts (5-D). Nonetheless, it is also suggested that this participation is underdeveloped, so youth experience limits to become part of rural communities (2-D, 4-D). Finally, regarding the gender gap, it was concluded that being female in rural contexts supposes a disadvantage for social, economic, or political participation (1-D). On the other hand, those studies focused on the diagnosis of rural youth challenges and potentials concluded that rural youth could participate in agricultural labors and socio-political and economic activities (e.g., public administration) (2-D). To take advantage of this, they must be empowered and supported (3-D).

Discussion

Rural youth research approaches

The first three categories identified (rural youth migration, rural youth education and communication, and rural youth expectations or perspectives) coincided with results discussed by Kessler (2006) in a review about rural youth in Latin America. Regarding the migration approach (addressed by 26 % of studies that were analyzed), because of its impact on the sociodemographic development in Latin American countries and the rural youth decision-making process, it has been highlighted as a relevant issue by international development institutions (e.g., Cazzuffi & Fernández, 2018; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC], 1995; ECLAC et al., 2012; Guiskin et al., 2019). Moreover, approaches related to rural youth education and/or communication and rural youth expectations (addressed by 15 and 13 studies, respectively) were recommended as a topic to work on (or to research about) by FAO and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2014). In summary, most of the studies focused on these three approaches are aligned with institutional, social, and regional requirements. The fourth approach (rural youth characterization or diagnosis) is aligned with the need for having reliable and updated data to undertake initiatives for rural development in developing countries (Contreras et al., 1998). Rural youth analysis papers, such as Guiskin et al. (2019) and Cazzuffi & Fernández (2018), are examples of the utility of this type of diagnosis to make public policy recommendations.

Methods

As described, most of the studies included in this review made a qualitative analysis (73 %). From the theoretical perspective, it is possible to explore rural issues and generate research findings using this inquiry method, especially in marginalized contexts (Harvey, 2010). However, a relevant element among documents with a qualitative analysis is that one-third of these studies did not report the inquiry approach (as explained by Creswell, 2007). This fact could suppose a limitation for generalizing research findings. For qualitative methods, the research rigor is strongly connected to the justification of the methodological choice (Carter & Little, 2007).

Moreover, another issue identified in qualitative ethnographic studies is that some of them based their analysis on data collected via interviews. Although we are not saying that they did not conduct analyses with ethnographic elements, their data collection procedure was not aligned with conventional methods of ethnographic studies, as defined by Jones et al. (2013). Regarding studies in which a quantitative analysis was used (i.e., quantitative and mixed-method analyses), only two of them reported a probabilistic sample, which implied a limitation for making statistical inferences from the results obtained by authors. In this sense, FAO (2015) suggested that it is essential to use surveys with statistical representativeness for studies with rural populations in Latin America. Finally, studies that performed a mixed-method analysis did not state how qualitative and quantitative data were contrasted or compared (aka, data triangulation). This triangulation is a key element in the analysis and conceptualization of this kind of method (Fielding, 2012) and should be conducted and stated in mixed-method studies.

Participants

The observed differentiation in the criterion to select participants could be associated to the breadth of the youth concept, especially in the rural context. Although youth is defined in general terms as those persons between the ages of 15 and 24 years (United Nations, 1981), some authors have increased this range up to 29 (Román, 2003) or 40 years (Becerra, 2002). Based not only on the age-perspective but also on the sociological analysis, the definition of youth implies a contextual dynamic, in which aspects such as family relations, education, labor, and socio-political participation, play an essential role (Kessler, 2005). As such, the definition of research participants focused on youth depends on the context.

Findings

As a common element to the four approaches identified, authors concluded and suggested that rural contexts put up barriers for rural youth. That is, because of a lack of resources (e.g., land, jobs, family support, and income), rural youth motivations and expectations are more oriented toward urban activities. Therefore, they envisioned migration (to urban areas) as a real (or better) alternative for their career advancement. These findings were aligned with the unequal development between urban and rural areas in Latin America, which means unequal access to social opportunities for those living in rural areas (especially young people). This social inequality is defined as a social boundary (Lamont & Molnár, 2002). Authors such as Berdegué et al. (2015), Kay (2006), and De Janvry and Sadoulet (2000) have explained the socioeconomic gap between urban and rural areas in Latin America as the main factor for migration or reduced economic opportunities for rural youth.

Another relevant finding was the importance of the education or extension activities to engage rural youth in rural activities. A study conducted by FAO & UNESCO (2004) concluded that, because of the singularities of the rural context, rural youth require education programs focused on specific rural issues (e.g., agriculture or natural resources), helping them to bridge the gap with urban people.

Conclusions

In general, the documents included in this review addressed relevant topics concerning rural youth in Latin America. Four approaches identified have not only been discussed by the scientific community, but also highlighted by public policy institutions as topics to research about (to empower and support rural youth). Researchers should consider these findings to broaden the knowledge related to rural youth in Latin America.

Regarding the discussion of methods and methodologies (which is the innovative element of this manuscript in comparison to previous papers), although authors used different strategies, elements such as the qualitative inquiry approach, the statistical representativeness (for quantitative studies), and the triangulation strategy in the mixed-method analysis were not correctly followed. We recommend that future studies strengthen methodological issues to ensure representativeness, generalizability, or reliability. Finally, it can be concluded that rural areas create barriers for rural youth development; therefore, public policies should bridge the gap between urban and rural areas.

The main limitation of our review was that there are not enough studies per country to conduct multilevel analysis (i.e., analyze differences for each approach among countries).