Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras - INVEMAR

versión impresa ISSN 0122-9761

Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost. vol.44 no.2 Santa Marta jul./dic. 2015

FIRST CHARACTERIZATION OF THE PLANKTONIC COMMUNITY IN THE NORTHERN SECTOR OF THE JOINT REGIME AREA JAMAICA - COLOMBIA

PRIMERA CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA COMUNIDAD PLANCTÓNICA DEL SECTOR NORTE DEL ÁREA DE RÉGIMEN COMÚN JAMAICA-COLOMBIA

José Manuel Gutiérrez-Salcedo1, Angélica Cabarcas-Mier2 and Nancy Suárez-Mozo3

1 Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (Invemar), Museo de Historia Natural Marina de Colombia (MHNMC). Playa Salguero, Santa Marta, Colombia. jose.gutierrez@invemar.org.co.

2 Cartagena, Colombia. angelicacabarcas@gmail.com.

3 Barranquilla, Colombia. nancy-yolimar@hotmail.com.

ABSTRACT

The Joint Regime Area Jamaica-Colombia (JRA) is a sector of economic importance for Colombia but its biodiversity is unknown due to the difficult access. Therefore, the Institute of Marine and Coastal Research - Invemar in agreement with the National Hydrocarbon Agency - ANH, made an expedition in 2011 to obtain a first approximation to the diversity of the JRA. Within the groups studied was the plankton, which was collected around landforms at 21 sampling stations in the northern sector of the JRA, with special plankton nets of 20 µm pore size mesh for phytoplankton and 200 µm for zooplankton. Organisms were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic category and an ecological analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, univariate and multivariate. 183 morphospecies of phytoplankton and 57 taxa (family and phylum) of zooplankton were identified, generating three geographically differentiated associations. The phyto and zooplankton found in the JRA is part of the plankton community typical of oligotrophic tropical oceanic waters and local differences could be due to ocean dynamics between the Caribbean Current Surface and landforms of the of San Andrés and JRA archipelago .

KEY WORDS: Phytoplankton, Zooplankton, Joint Regime Area.

RESUMEN

El Área de Régimen Común Jamaica-Colombia (ARC) es un sector de importancia económica para el país pero de difícil acceso, desconociéndose en la actualidad su biodiversidad. Por ello el Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras, en convenio con la Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos, realizó una expedición en 2011 para obtener una primera aproximación a la diversidad del ARC. Dentro de los grupos estudiados estuvo el plancton, por lo que se requirió recolectar muestras en 21 estaciones dentro del sector norte del ARC, alrededor de las geoformas, con redes especializadas de 20 µm de poro de malla para fitoplancton y 200 µm para zooplancton. Los organismos fueron identificados a la categoría taxonómica más baja posible y se realizó un análisis ecológico a partir de estadísticos descriptivos, univariados y multivariados. Se identificaron 183 morfoespecies de fitoplancton y 57 grupos taxonómicos (familia y phylum) de zooplancton, generándose tres asociaciones diferenciables geográficamente. El fito y zooplancton encontrados en el ARC hace parte de la comunidad planctónica de aguas típicas tropicales oceánicas oligotróficas (ATTOO) y las diferencias locales se pudieron deber a la dinámica oceánica entre la Corriente Superficial del Caribe y a las geoformas del archipiélago de San Andrés y del ARC.

PALABRAS CLAVES: Fitoplancton, Zooplancton, Área de Régimen Común.

INTRODUCTION

One of the main biological components of the pelagic medium is plankton or organisms that can not maintain their spatial distribution, independently of the movement of water masses (Parsons et al., 1984). Among them are several autotrophic and unicellular organisms such as diatoms, dinoflagellates, and blue-green algae, that make part of phytoplankton (Dawes, 1986; Tait, 1987) plus individuals that are part of all the phyla of marine invertebrates, and fish eggs and larvae, as permanent or partial residents of the community, that make part of zooplankton (Parsons et al., 1984). Those groups are important because they control the flow of energy of the marine environment (Raymont, 1983; Bathman et al., 2001), positively intervene, at a macro scale, in climatic change (Franco-Herrera et al., 2006), in the distribution of many species (Mujica, 2006), and are good indicators of the ecological state of the system (Daly and Smith, 1993; Pinel-Alloul, 1995).

The planktonic community of the Colombian Caribbean Sea (CCS) is characterized by a group of stable and mature assemblies, typical of a tropical oligotrophic system (Gutiérrez-Salcedo, 2011). Those assemblies change depending on their location, showing high abundance and low richness in coastal locations (Bernal, 2000). This pattern of abundance and richness is inverted as they move further away from the coast and the oceanic region shows the least abundant and richest assemblies (Lozano-Duque et al., 2010). Ecologically, the planktonic community of the CCS presents low productive in comparison with other regions (Franco-Herrera, 2006) and is mainly dominated by dinoflagellates, diatoms, and cyanobacteria (phytoplankton) (Franco-Herrera et al., 2006); and copepods, larvaceans and chaetognaths (zooplankton) (Gutierrez-Salcedo, 2011).

Among the studies performed in the CCS, 190 species from 69 phytoplankton genera have been described fromthe insular region (Herrera, 1985; Garay et al., 1988; Téllez et al., 1988; Campos-González, 2007; Vargas-Castellanos, 2008) and 235 zooplankton species, of which 150 were holoplankton (Giraldo and Villalobos, 1983; Mulford, 1983; Márquez and Herrera, 1986; Martínez-Barragán, 2008; Martínez-Barragán et al., 2008) and 85 fish larvae (Godoy and Escobar, 1983; Lara and Cabra, 1984). These studies suggest that the Archipelago’s planktonic community, with relation to those found in the coastal and oceanic regions of the Colombian Caribbean, present a lesser productivity; it is dominated by cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates at the phytoplankton level, while at the zooplankton level the same groups are maintained; and the trophic tendency is closer to a herbivorous system.

However, none of the studies were performed in the Joint Regime Area (JRA) Jamaica-Colombia, an area of current and future high importance for the country, politically as well as economically and environmentally (Invemar, 2012). Therefore, an interinstitutional cooperation agreement between the National Hydrocarbon Agency (ANH) and the Marine Research Institute (Invemar) was reached in order to carry out the base environmental line for the JRA as contribution to sustainable exploitation of the shared marine resources (Agreement No. 16 from 2010). To accomplish this agreement the planktonic community at the JRA was preliminary evaluated in order to generate the information needed to produce management guidelines for the JRA so that Colombia and Jamaica may adequately use the existing resources.

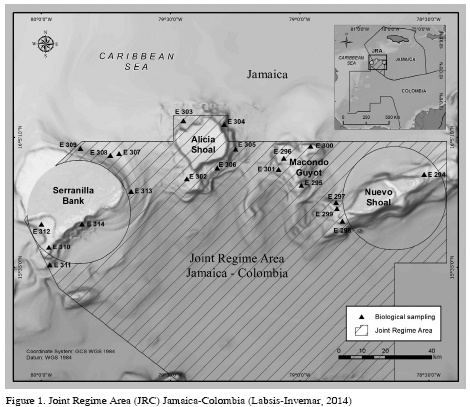

STUDY AREA

The JRA was created through the Sanin-Robertson treaty on November 12 of 1993, between the republics of Jamaica and Colombia to manage, do research, preserve, and exploit its maritime areas rationally and jointly. The region is a polygon with an approximate area of 15000 km2 and a depth of more than 1.5 km (Invemar, 2012) (Figure 1). Geographically it is located northeast of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina Archipelago, within the lower Nicaraguan Ridge (Case et al., 1984). To the north it evidences a variety of geomorphological features such as the Serranilla bank, the Alicia and Nuevo shoals and the Macondo guyot (Geister and Díaz, 2002). A more detailed description of the study area is available in Invemar (2012).

Three water masses have been described within the area up to 1000 m depth (Wüst, 1964), of which the most superficial is the Caribbean Superficial Water -of the Caribbean - CSW found at the upper 50 to 75 m (González, 1987). This water mass flows to the northeast due to the Caribbean Superficial Current. - CSC. However, thanks to the bottom configuration several eddys are generated which are more prominent during July and October, generating more dynamics and thus a lesser oceanographic homogeneity at lesser scales (Andrade et al., 1996).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The expedition took place between October the 11th and November the 9th 2011, on board of the multi-purpose towboat Don Rodrigo B. The samples were got at 21 stations located around the four main geomorphological traits of the CRA (i.e. Alicia and Nuevo Shoals, Macondo Guyot, and Serranilla Bank) (Figure 1). To achieve this, plankton nets were used with lengths of 2.2 m, 60 cm opening, and 20 µm mesh size of for phytoplankton and 200 µm for zooplankton. A previously calibrated flowmeter was used for the zooplankton net using revolutions to calculate speeds. In both cases, the nets were initially lowered to a depth of approximately 50 m, and subsequently dragged horizontally at an average speed of 1 m/s for 10 min, and later raised on board. The organisms that were trapped in the collector were transferred to 500 mL plastic containers, adding as a formaldehyde solution neutralized with sodium tetraborate as preservative, resulting in a final preservative sea water concentration of 5%. The samples were stored in dry places while they were taken to the lab for their posterior observation and identification.

Organisms in each sample were identified and accounted to the lowest possible taxonomical category with the help of an inverted microscope and a stereoscope, and following the morphological diagnostic characteristics for each of them (phytoplankton: Boyer, 1927; Cupp, 1943; Taylor, 1976; Balech, 1988; Round, 1990; Hasle and Syvertsen, 1997; Steidinger and Tangen, 1997; Soler et al., 2003. Zooplankton: Alvariño, 1963; Newell and Newell, 1963; Boltovskoy, 1981; Campos and Suárez, 1994; Conway et al., 2003; Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). Two aliquots of two millimeters per sample were used, counting 30 random fields in a Sedwigck-Rafter chamber for phytoplankton (McAlice, 1971). Fractions containing 1000 organisms per zooplankton sample were observed in Petri dishes. To achieve this, the samples were divided using a Folsom fractionator following Sell and Evans (1982) recommendations and those of De Oliveira-Diaz et al. (2010). The samples were divided a maximum of three times, verifying at least an eighth of the original sample. When performing the Relative Percent Difference statistic, no sample exceeded 19%, which leads to the conclusion that the divisions were properly done (Anonymous, 1994). Additionally, the protocols proposed by Harris et al. (2000) were used for the zooplankton samples to obtain biomass.

The information obtained from identification and accounting of the organisms in both groups was tabulated in independent matrixes, obtaining an organism percent abundance for phytoplankton and individuals per cubic meter for zooplankton. In both cases matrixes were constructed in relation to the sampled stations.

Before multivariate analysis and in order to verify the existence of anomalous data, a Z transformed table was done for each morphotype as well as for the stations. The results did not exceed the established threshold of three, so no data was eliminated (Morón, 2011). A multivariate non-parametric descriptive analysis of quantitative classification was done for both groups (Cluster), based on a triangular similitude matrix (Bray-Curtis index), in order to determine any association trend of the stations. Additionally, a one-way spatial association distribution (Anosim) was done for the zooplankton matrix to corroborate the association statistically. These routines were performed in the statistical software Primer-E v.5. (Clarke and Warwick, 1994).

In order to characterize and differentiate associations, ecological richness (S), Pielou uniformity (J’), and Shannon diversity (H’) were found for both groups. Additionally, a beta richness (βw) analysis was done for phytoplankton and an abundance (N), Simpson dominance (λ), Shannon Maximum diversity (H’ max), and Hill diversity (N1) analyses were performed for zooplankton (Clarke and Warwick, 1994). As for the multivariate analyses, the indexes obtained for zooplankton were statistically compared using a Mann-Whitney test (non-parametric test), adding to the comparison the dry biomass and organic matter values obtained from the protocol proposed by Harris et al. (2000). Finally, ecological descriptions were made for each association, detailing each of the specificities as per flora and fauna composition of the phytoplankton and zooplankton.

RESULTS

One hundred and thirty-eight phytoplankton morpho-species were analyzed, with diatoms, dinoflagellates, and cyanobacteria as the most representative groups (Annex 1). While there were 57 taxonomical groups described for zooplankton (family and phylum), the most abundant were copepods (phylum Arthropoda), mainly within the Calanoida order representing 68% of total abundance, and larvaceans (phylum Chordata) (Annex 2).

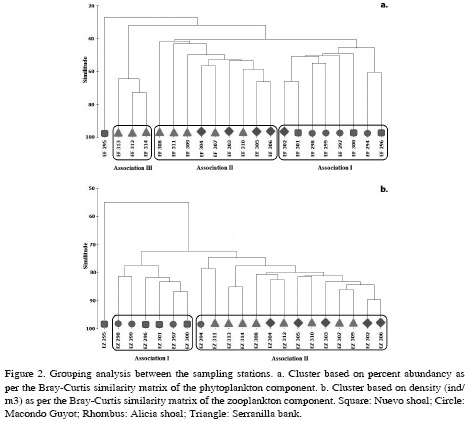

The dendrograms allowed determining that the samples were grouped following a geographical pattern (Figure 2). Most stations of the Nuevo Shoal and Macondo Guyot were in Association I, while those of Alicia Shoal and Serranilla Bank were grouped in Association II. Association III only contained phytoplankton assembly and was composed by three stations of the Serranilla Bank. Lastly, for both planktonic groups, the independent station was the same and belonged to the Macondo Guyot.

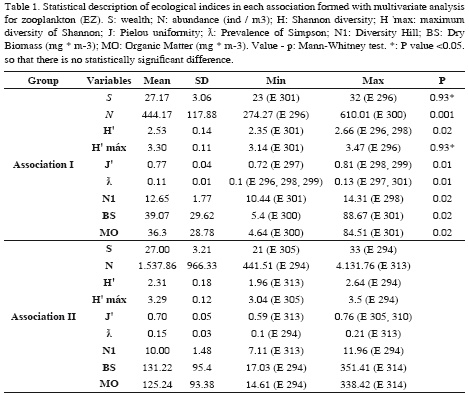

Associations made up for the zooplankton assembly presented structurally significant statistic differences (Global Anosim R: 0.699 [p = 0.1%]). All associations presented low predominance, high uniformity and diversity close to the maximum (Annex 3), finding statistical differences between the stations associated to an abundance dependency (N, H’, J’, ƛ, N1) (Table 1).

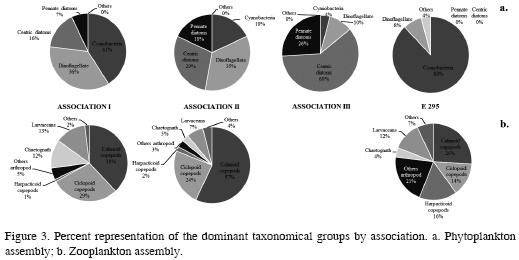

Association I was characterized because dinoflagellates were the phytoplankton group with the highest number of morphospecies and most abundant, in terms of percentage (41%), cyanobacteria (Figure 3a), with Oscillatoria and Richelia as the most representative genera (Annex 1). As far as the zooplankton assembly, the phylum Arthropoda contained the largest number of morphotypes and the highest abundance, mainly of the order Calanoida, with 68 % of the total association (Figure 3b). In terms of families, Corycaeidae, Oncaeidae (copepods), Oikopleuridae (larvaceans), and Sagittidae (chaetognaths), and crustacean larvae were the most abundant, with over 15 ind/m3 (Annex 2).

Association II was characterized by a dominance in diversity and abundance of diatoms, close to 50% of the total association, followed closely by dinoflagellates (≈ 37%) (Figure 3a). While in the zooplankton assembly, calanoid copepods from the Paracalanidae, Calanidae, Calusocalanidae, and Acartiidae families were the most representative, although the most abundant were also representatives of the polychaetes Iospidae and Lopadorhynchidae, amphipod Hyperiidae and Oxycephalidae, and other copepods such as Toranidae. In this association, the most representative juveniles were echinoderm and fish larvae with over 50 ind/m3 .

Association III was characterized for presenting a dominance in richness and percent abundance of diatoms in the phytoplankton assembly, mainly of the central ones (≈ 50% representation) (Figure 3a), decreasing in abundance but not in richness of dinoflagellates, and resulting in low abundance and richness of cyanobacteria. Lastly, station E 295 was characterized because cyanobacteria did not have the greatest percentage abundance while it shared richness representation with dinoflagellates (Figure 3a). Diatoms were barely present. On the other hand, the zooplankton assembly was represented by harpacticoidean copepods of the family Miraciidae and among the juveniles (juvenile holoplankton and meroplankton) copepodites and nauplii, with more than 90% of the total study (Figure 3b).

DISCUSSION

The plankton assemblies studied in the northern JRA showed composition characteristics, relative abundance, density, and ecological indexes similar to those found for other assemblies in the upperwater mass (UCW) in the tropical region (Margalef, 1969; Deevy and Brooks, 1971; Longhurst and Harrison, 1989), the Caribbean (Carbonell, 1981; Hopcroft et al., 1998a, 1998b; Weber et al., 2005) and the CSC (Garay et al., 1988; Téllez et al., 1998; Medellín-Mora and Martínez-Ramírez, 2010; Gutiérrez-Salcedo, 2011). This community is characterized for having at least 100 phytoplankton species dominated by diatoms, although in some cases dinoflagellates maybe more important and in others even cyanobacteria. There are also more than 50 zooplankton families and their abundance in this group exceeds 500 ind/ m3. In composition as well as in abundance copepods are 60% or more of the group. Also, these assemblies show low predominance and high uniformity and diversity, close to the maximum. All these characteristics allow cataloguing the assemblies in this study within the planktonic community of typical oligotrophic oceanic tropical waters (TOOTW) (Longhurst, 1982a, 1985b; Longhurst and Harrison, 1989).

The lack of oceanographic information in the study area does not allow relating the biological community to its environment and thus compare it to other studies. Therefore, the following analyses are assumptions or hypothesis about the structure of the assemblies at a local scale are based on other studies with similar biological information.

The presence of different associations was mainly conditioned by the relative and total abundance of phyto and zooplankton, respectively, evidencing that association II (Alicia Shoal and Serranilla Bank) abundances where 10 times higher than those of association I (Nuevo Shoal and Macondo Guyot). The third phytoplankton association differed from the second one due to composition aspects that show a greater dominance of central diatoms. The only station showed the lowest abundance with a dominance of cyanobacteria and harpacticoids.

As mentioned, these associations are conformed geographically. Association II is found towards the western sector of the JRA, while the other two associations and Station E 295 are located on the other side. The possible separation may be due to the geophysical structure and ocean dynamics, creating associations due to mainly physical actions because they generate ideal environmental conditions or a combination of both.

The first assumption or hypothesis is that the greater abundance of association II is due to a purely physical grouping of the planktonic community. This may be due to the confluence of the internal meanders of the CSC that arrive to the area from San Andrés (Garay et al., 1988) and the geophysical formation of Serranilla Bank and Alicia Shoal, with peaks closer to the surface and a larger area than those of the other sector (Macondo Guyot and Nuevo Shoal) (Vega-Sequeda et al., 2015). These two characteristics accelerate the flow of the water mass preventing plankton from moving from one place to the other and causing an agglomeration near the formations. This situation has been proven in other studies, such as the one by Incze et al. (2001), who showed that a simple collision between ocean fronts resulted in abundance of the planktonic community.

The second assumption or hypothesis is that the area of association II shows conditions that favors the growth of the planktonic community due to a larger food offer. This may be possibly based on: 1) that the Serranilla Bank and Alicia Shoal (Association II) show a greater diversity of food for the planktonic community; 2) These two geomorphological traits have an area that doubles that of the other two geomorphological traits (Macondo Guyot and Nuevo Shoal -Association I-), therefore creating a larger area for benthic diversity to generate a larger food offer; and 3) the current that passes through Serranilla Bank and Alicia Shoal is shallower, allowing for a constant resuspension of the nutrients necessary for planktonic growth. This behavior has been evidenced in other studies of the region were it was found that a water mass that arrives to San Andrés on its southern side causes a phytoplankton bloom, mainly of diatoms, which generates a larger zooplankton growth evidenced in the northwestern side (Campos-González, 2007; Martínez-Barragán, 2007).

For the case of station E 295, located close to the Macondo Guyot, association I was possibly separated due to another oceanographic factor. Studies of submarine mountains have shown that when a current passes through them it may generate a vertical anticyclonic circulation cell, creating a different space than the rest of the sector with a possible low interaction of planktonic assemblies (Hamner and Hauri, 1981; Genin, 2004).

The composition of the species of each association allows corroborating that they are the same community but that due to local conditions they are differently structured, supporting the aforementioned hypotheses. Association I is dominated by filamentous cyanobacteria, organisms that take nitrogen from the atmosphere and proliferate when nutrients are poor and the waters are calm (Margalef, 1972; Gómez et al., 2005). A greater proportion of dinoflagellates than diatoms were also found, confirming the water mass oligotrophy (Margalef, 1972). These organisms are the food for the copepod family Corycaeidae (Kleppel and Piper, 1984) and larvaceans (Allredge and Silver, 1988; Steinberg et al., 1993), zooplankters with the largest abundance in the association. This last group produces marine snow that allows cyanobacteria to proliferate easier, as well as copepods of the family Oncaeidae because it provides substrates for them to feed of these algae (Steinberg et al., 1994). The presence of carnivores such as chaetognaths with medium abundances in comparison to the other groups allows to conclude that this assembly shows a classic trophic network (Sullivan, 1980). Lastly, the larger quantity of crustacean larvae in this association would lead us to conclude that possibly the benthic communities of Nuevo Shoal and Macondo Guyot could contain high abundance of these organisms.

Association II was dominated by diatoms which is why the water in this sector showed input of a larger quantity of nutrients in relation to the previous association (Margalef, 1972). Being responsible for productivity, the trophic network would be composed of larger organisms, corroborating the presence of polychaetes (Halanych et al., 2007). This would also attract a larger diversity of carnivores such as amphipods and copepods of the family Tortanidae, as well as chaetognaths (Wickstead, 1959; Gasca and Shih, 2001). Also, high predation would cause much of the particulate organic matter to be used by the omnivore and detrivore species such as the families Paracalanidae (Stoecker and Sanders, 1985), Calanidae, Clausocalanidae (Kleppel et al., 1988; McKinnon, 1996) and Acartiidae (De Oliveira-Díaz et al., 2010), groups with medium abundance in this association and that also feed on diatoms. Lastly, just like in the previous association, benthic communities in the shallows of the submarine accidents Alicia Shoal and Serranilla Bank may have a high abundancy of echinoderms and fish, as evidenced in the work of Vega-Sequeda et al. (2015).

Association II only includes phytoplankton. This situation could be due to the response time of this community to environmental changes, which is hours or a few days, while the zooplankton reacts only after one week (Margalef, 1972). The presence with greater relative abundance of genera such as Chaetoceros, Bacteriastrum, Pseudonitzschia, and Leptocylindrus would let to infer that the water mass presents coastal conditions since they are typical of these systems (Garay et al., 1988) and could have been brought by the current from the Magdalena river (Cañón-Páez and Santamaria del Ángel, 2003) or the Panama-Colombia Gyre, affecting the study area an modifying its planktonic structure (Martínez-Barragán, 2007; Gutiérrez-Salcedo, 2011).

Lastly, the E 295 station was characterized by a dominance of crococale cyanobacteria that grow in more calm water conditions and with high solar incidence (Margalef, 1972), generating large enough aggregations so that organisms such as copepods from the harpacticoidean group seek refuge and food to proliferate (Calef and Grice, 1966; Roman, 1978; Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). Additionally, confirm a possible vertical cell over the guyot because these organisms are strongly related to very calm waters (Boltovskoy, 1981; Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). However, due to the absence of physical data it is just a hypothesis yet to be proven.

CONCLUSIONS

The northern sector of the JRA showed a planktonic community categorized as coming from typical tropical oceanic oligotrophic waters. The associations found were geographical and quite possibly controlled by ocean dynamics.

The western sector (Alicia Shoal and Serranilla Bank) showed a community structure dominated by diatoms and calanoids, a characteristic of waters with contributions of nutrients and organisms of a larger trophic network than the one in the eastern sector (Nuevo Shoal and Macondo Guyot), which presented organisms of oligotrophic and calm waters with smaller body sizes such as filamentous cyanobacteria and poecilostomatoid copepods.

The separation of station E 295 could be due to an oceanic condition, a circulation cell generated by the guyot, isolating the assembly and generating a condition for proliferation of crococal cyanobacteria and harpacticoideans.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the executive Invemar personnel for their help, especially General Director Francisco Arias Isaza and the Biodiversity and Marine Ecosystems Program Director, David Alonso. They would also like to thank the Government of Jamaica, the Governor of San Andres and Providencia, the Providencia Mayor’s Office, the Dimar (Providencia Regional Office), the Petroleum Corporation of Jamaica (PCJ) and the National Hydrocarbon Agency (ANH) of Colombia, who sponsored most of this research thanks to Agreement No. 016 of 2010. The samples were collected by virtue of Decree 309 of 2003 of the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development.

LITERATURE CITED

Alldredge, A.L. and M.W. Silver. 1988. Characteristics, dynamics, and significance of marine snow. Prog. Oceanogr., 20: 41-82. [ Links ]

Alvariño, A. 1963. Quetognatos epiplanctónicos del mar de Cortés. Rev. Soc. Mex. Hist. Nat., 24: 98-203. [ Links ]

Andrade, C., L. Geraldo and S. Lonin. 1996. Nota sobre la circulación de las aguas en el bajo Alicia y el sector de San Andrés islas. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 17: 27-36. [ Links ]

Anónimo. 1994. Standard operating procedure for zooplankton analysis. Grace Analytical Lab. Chicago-USA. 23 p. [ Links ]

Balech, E. 1988. Los dinoflagelados del Atlántico Sudoccidental. Publicaciones Especiales del Instituto Español de Oceanografía. Vigo. 310 p. [ Links ]

Bathmann, U. , M.H. Bundy, M.E. Clarke, T.J. Cowles, K. Daly, H.G. Dam, M.M. Dekshenieks, P.L. Donaghay, D.M. Gibson, D.J. Gifford, B.W. Hansen, D.K. Hartline, E.J.H. Head, E.E. Hofmann, R.R. Hopcroft, R.A. Jahnke, S.H. Jonasdottir, T. Kiørboe, G.S. Kleppel, J.M. Klinck, P.M. Kremer, M.R. Landry, R.F. Lee, P.H. Lenz, L.P. Madin, D.T. Manahan, M.G. Mazzocchi, D.J. Mcgillicuddy, C.B. Miller, J.R. Nelson, T.R. Osborn, G.A. Paffenhöfer, R.E. Pieper, I. Prusova, M.R. Roman, S. Schiel, H.E. Seim, S.L. Smith, J.J. Torres, P.G. Verity, S.G. Wakeham and K.F. Wishner. 2001. Future marine zooplankton research. A perspective. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 222: 297-308. [ Links ]

Bernal, A. 2000. Die struktur der zooplanktongemeinschaft im neritischen Bereich des Kolumbianischen karibischen meeres. Ph.D. dissertation, Justus Liebig Universitat, Giessen, Germany. [ Links ]

Boltovskoy, E. 1981. Atlas del zooplancton del Atlántico Sudoccidental y métodos de trabajo con el zooplancton marino. Inidep, Mar del Plata, Argentina. 891 p. [ Links ]

Boxshall, G.A. and S.H. Halsey. 2004. An introduction to copepod diversity: Part I-II. The Ray Society, London. 966 p. [ Links ]

Boyer, C. 1927. Sinopsis of North American Diatomaceae. Part II: Naviculate and Surirellate. Acad. Nat. Sci., 230-583. [ Links ]

Calef, G.W. and G.D. Grice. 1966. Relationship between the blue-green alga Trichodesmium thiebautii and the copepod Macrosetella gracilis in the plankton off Northeastern South America. Ecology, 47(5): 855-856. [ Links ]

Campos, A. and E. Suárez. 1994. Copépodos pelágicos del golfo de México y mar Caribe. Biología y Sistemática. Centro de investigaciones de Quintana Roo. México. 357 p. [ Links ]

Campos-González, E.M. 2007. Fitoplancton de las islas de Providencia y Santa Catalina, Caribe colombiano. Marine Biology thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Santa Marta. 77 p. [ Links ]

Cañón-Paez, M.L. and E. Santamaría del Ángel. 2003. Influencia de la pluma del río Magdalena en el Caribe colombiano. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 21: 85-90. [ Links ]

Carbonell, M. 1981. Fitoplancton de República Dominicana. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 3: 11-52. [ Links ]

Case, J.E., T.L. Holcombe and R.G. Martin. 1984. Map of the geological provinces in the Caribbean region. p. 1-31. En: Bonini, W., R. Hargraves and R. Shangan (Eds.). The Caribbean South America plate boundary and regional tectonics. Geological Society of America, Memoir 162. 131 p. [ Links ]

Clarke, K.R. and R.M. Warwick. 1994. Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. Natural Environment Research Council, Plymouth. 141 p. [ Links ]

Conway, D.R. White, J. Hugues-Dit-Ciles, C. Gallienne and D. Robins. 2003. Guide to the coastal and surface zooplankton of the south western Indian Ocean. Occasional Publication of the Marine Biological Association No. 15. Plymouth-UK. No. 15. 356 p. [ Links ]

Cupp, E. 1943. Marine plankton of the west coast of North America. Bull. Scripps Inst. Oceanogr. Univ. Calif., 5(1): 1-138. [ Links ]

Daly, K.L. and W.O. Smith. 1993. Physical-biological interactions influencing marine plankton production. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 24: 555-585. [ Links ]

Dawes, C. 1986. Botánica marina. Limusa, México D. F. 672 p. [ Links ]

Deevey, G.B. and A.L. Brooks. 1971. The annual cycle in quantity and composition of the zooplankton of the Sargasso Sea off Bermuda. II. The surface to 2000 m. Limnol. Oceanogr., 16(6): 927-943. [ Links ]

De Oliveira-Díaz, C., A. Valente De Araujo, R. Paranhos and S.L. Costa-Bonecker 2010. Vertical copepod assemblages (0-2300 m) off Southern Brazil. Zool. Stud., 49(2): 230-242. [ Links ]

Franco-Herrera, A. 2006. Variación estacional del fitoplancton y mesozooplancton e impacto de herbivoría de Eucalanus subtenuis, Giesbrecht, 1888 (Copepoda: Eucalanidae) en el Caribe colombiano. Ph.D. dissertation Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile. 125 p. [ Links ]

Franco-Herrera, A., L. Castro and P. Tigreros. 2006. Plankton dynamics in the South-Central Caribbean Sea: Strong seasonal changes in a coastal tropical system. Caribb. J. Sci., 42(1): 24-38. [ Links ]

Garay, J., F. Castillo, C. Andrade, J. Aguilera, L. Niño, M. de La Pava, W. López and G. Márquez. 1988. Estudio oceanográfico del área insular y oceánica del Caribe colombiano-Archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia y cayos vecinos. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 9: 3-73. [ Links ]

Gasca, R. and C.T. Shih. 2001. Hyperiid amphipods from surface waters of the western Caribbean Sea. Crustaceana, 74(5): 489-499. [ Links ]

Geister, J. and J.M. Díaz. 2002. Ambientes arrecifales y geología de un archipiélago oceánico: San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina. Mar Caribe, Colombia (Guía de campo). INVEMAR, Santa Marta. 114 p. [ Links ]

Genin, A. 2004. Biophysical coupling in the formation of zooplankton and fish aggregations over abrupt topographies. J. Mar. Syst., 50: 3-20. [ Links ]

Giraldo, R.A. and S.A. Villalobos. 1983. Composición y distribución del zooplancton superficial de San Andrés y Providencia y su relación con algunos parámetros fisicoquímicos: Crucero Océano V, Área I. Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá. 82 p. [ Links ]

Godoy, L.D and O.J.C. Escobar. 1984. Descripción, distribución y abundancia del ictioplancton para el archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia (crucero Oceano V, Área I, septiembre-octubre, 1981). Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá. 479 p. [ Links ]

Gómez, F., Y. Furuya and S. Takeda. 2005. Distribution of the cyanobacterium Richelia intracellularis as an epiphyte of the diatom Chaetoceros compresssus in the Western Pacific Ocean. J. Plankton Res., 27(1): 323-330. [ Links ]

González, E. 1987. Oceanografía física descriptiva del archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia, con base en el análisis de los cruceros Océano IV A IX. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 7: 73-100. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-Salcedo, J.M. 2011. Estructura vertical del zooplancton oceánico del mar Caribe colombiano. M.Sc. Thesis , Marine Biology, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. 124 p. [ Links ]

Halanych, K.M., L.N. Cox and T.H. Struck. 2007. A brief review of holopelagic annelids. Integr. Comp. Biol., 47(6): 872-879. [ Links ]

Hamner, W.M. and I.R. Hauri. 1981. Effects of Island mass: Water flow and plankton pattern around a reef in the Great Barrier Reef Lagoon, Australia. Limnol. Oceanogr., 26(6): 1084-1102. [ Links ]

Harris, R.P., P.H. Wiebe, J. Lenz, H.R. Skjoldal and M. Huntley. 2000. Zooplankton methodology manual. Academic Press, London. 707 p. [ Links ]

Hasle, G.R. and E.E. Syvertsen. 1997. Marine diatoms. En: Thomas C. R. (Ed). Identifying marine phytoplankton. Academic Press, San Diego,. 385 p. [ Links ]

Herrera, M. 1985. Estudio en la abundancia del fitoplancton y su distribución geográfica durante el crucero Océano VII, Área I, Archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia. Biology Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. 153 p. [ Links ]

Hopcroft, R.R., J.C. Roff and D. Lombard. 1998a. Production of tropical copepods in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica: the importance of small species. Mar. Biol., 130: 593-604. [ Links ]

Hopcroft, R.R., J.C. Roff and H.A. Bouman. 1998b. Zooplankton growth rates: the larvaceans Appendicularia, Fritillaria and Oikopleura in tropical waters. J. Plankton Res., 20(3): 539-555. [ Links ]

Incze, L.S., D. Hebert, N. Wolff, N. Oakey and D. Dye. 2001. Changes in copepod distributions associated with increased turbulence from wind stress. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 213: 229-240. [ Links ]

Invemar. 2012. Línea base ambiental en el Área de Régimen Común Jamaica-Colombia como aporte al aprovechamiento sostenible de los recursos marinos compartidos. Final Report Agreement No. 016, 2010 (Invemar) and Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos (ANH), Santa Marta. 774 p. [ Links ]

Kleppel, G.S. and R.E. Pieper. 1984. Phytoplankton pigment sin the gut contents of planktonic copepods from coastal waters off southern California. Mar. Biol., 78: 193-198. [ Links ]

Kleppel, G.S., D. Frazel, R.E. Pieper and D.V. Holliday. 1988. Natural diets of zooplankton off southern California. Mar. Ecol. Ser. Progr., 49: 231-241. [ Links ]

Lara, D.G. and C.H.E. Cabra. 1984. Dinámica y distribución de larvas juveniles de peces de las especies pelágicas de interés comercial en el archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia (cruceros VI, VII, VIII, Área I, 1983-1984) (Reconocimiento preliminar).Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Cartagena. 80 p. [ Links ]

Longhurst, A.R. 1985a. Relationship between diversity and the vertical structure of the upper ocean. Deep-Sea Res., 32: 1535-1570. [ Links ]

Longhurst, A.R. 1985b. The structure and evolution of plankton communities. Progr. Oceanogr., 15: 1-35. [ Links ]

Longhurst, A.R. and W.G. Harrison. 1989. The biological pump: Profiles of plankton production and consumption in the upper ocean. Progr. Oceanogr., 22: 47-123. [ Links ]

Lozano-Duque, Y., L.A. Vidal and G.R. Navas. 2010. La comunidad fitoplanctónica en el mar Caribe colombiano. 87-118. En: Navas, G.R., C. Segura-Quintero, M. Garrido-Linares, M. Benavides-Serrato y D. Alonso (Eds.). Biodiversidad del margen continental del Caribe colombiano. Serie de Publicaciones Especiales No. 20, Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (Invemar), Santa Marta. 458 p. [ Links ]

Margalef, R. 1969. El ecosistema pelágico del mar Caribe. Mem. Soc. Cienc. Nat. La Salle, 29(32). 36 p. [ Links ]

Margalef, R. 1972. Regularidades en la distribución de la diversidad del fitoplancton en un área del mar Caribe. Invest. Pesq., 36: 241-264. [ Links ]

Márquez, G. and M. Herrera. 1986. Estudio de la biomasa fitoplanctónica y su distribución geográfica durante el crucero Océano área I: Archipiélago levantamiento Providencia en el Caribe colombiano. Final Report Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. 153 p. [ Links ]

Martínez-Barragán, M.P. 2007. Composición y abundancia del zooplancton marino de las islas de Providencia y Santa Catalina (Caribe colombiano), durante la época climática lluviosa (octubre-noviembre) de 2005. Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Santa Marta. 119 p. [ Links ]

Martínez-Barragán, M., A. Franco-Herrera, J. Medina-Calderón and A. Santos-Martínez. 2008. La comunidad de copépodos en las islas de Providencia y Santa Catalina (Caribe colombiano) durante el período lluvioso (octubre) 2005. Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost., 38(1): 85-103. [ Links ]

McAlice, B. 1971. Phytoplankton sampling with the Sedwigck-Rafter Cell. Limnol. Oceanogr., 16(1): 19-28. [ Links ]

Mckinnon, A.D. 1996. Growth and development in the subtropical copepod Acrocalanus gibber. Limnol. Oceanogr., 41(7): 1438-1447. [ Links ]

Medellín-Mora J. and O. Martínez-Ramírez. 2010. Distribución del mesozooplancton en aguas oceánicas del mar Caribe colombiano durante mayo y junio de 2008. 121-149. In: Navas, G. R., C. Segura-Quintero, M. Garrido-Linares, M. Benavides-Serrato and D. Alonso (Eds.). Biodiversidad del margen continental del Caribe colombiano. Serie de Publicaciones Especiales No. 20, Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (Invemar), Santa Marta. 458 p. [ Links ]

Morón, J. 2011. Señales y sistemas. Fondo Editorial Biblioteca. Universidad Rafael Urdaneta. Maracaibo. 242 p. [ Links ]

Mujica, A. 2006. Larvas de crustáceos decápodos y crustáceos holoplanctónicos en torno a la isla de Pascua. Cienc. Tec. Mar, 29: 123-135. [ Links ]

Mulford, A.L. 1983. Distribución de los chaetognatos en el archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia y su relación con algunos parámetros físico-químicos.Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano. Santa Marta. 96 p. [ Links ]

Newell, G. and R. Newell. 1963. Marine Plankton: practical guide. Unwin Hyman. London. 240 p. [ Links ]

Parsons, T.R., M. Takahashi and B. Hargrave. 1984. Biological oceanographic processes. Third edition, Pergamon Press, Oxford. 332 p. [ Links ]

Pinel-Alloul, B. 1995. Spatial heterogeneity as a multiscale characteristic of zooplankton community. Hydrobiologia, 300.301:17-42. [ Links ]

Raymont, J.E.G. 1983. Plankton and productivity in the oceans. Pergamon Press, Oxford. 825 p. [ Links ]

Roman, M.R. 1978. Ingestion of the blue-green alga Trichodesmium by the harpactacoid copepod, Macrosetella gracilis. Limnol. Oceanogr., 23(6): 1245-1248. [ Links ]

Round, F. 1990. Diatoms: The biology and morphology of the genera. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 747 p. [ Links ]

Sell, D.W. and M.S. Evans. 1982. A statistical analysis of subsampling and an evaluation of the Folsom plankton splitter. Hydrobiologia, 94: 223-230. [ Links ]

Soler, A., M. Pérez and E. Aguilar. 2003. Diatomeas del Pacífico en Panamá, estudio florístico. Agenda del Centenario de la Universidad de Panamá. Panamá. 383 p. [ Links ]

Steidinger, K.A. and K. Tangen. 1997. Dinoflagellates. En: Tomas C.R. (Ed) Identifying marine phytoplankton. Academic Press. San Diego. 387-584. [ Links ]

Steinberg, D.K., M.W. Silver, C.H. Pilskaln, S.L. Coale and J.B. Paduan. 1994. Midwater zooplankton communities on pelagic detritus (Giant Larvacean Houses) in Monterey Bay, California. Limnol. Oceanogr., 39(7): 1606-1620. [ Links ]

Stoecker, D.K. and N.K. Sanders. 1985. Differential grazing by Acartia tonsa on a dinoflagellate and a tintinnid. J. Plankton Res., 7: 85-100. [ Links ]

Sullivan, B.K. 1980. In situ feeding behavior of Sagitta elegans and Eukrohnia hamata (Chaetognatha) in relation to the vertical distribution and abundance of prey at ocean station "P". Limnol. Oceanogr., 25(2): 317-326. [ Links ]

Tait, R. 1987. Elementos de ecología marina. Ed. Acribia, Zaragoza, Spain. 446 p. [ Links ]

Taylor, E.J.R. 1976. Dinoflagellates from the international Indian Ocean expedition. A report on material collected by the "Anton Bruun" 1963-1964, 132, Stuttgart, 234 p. [ Links ]

Téllez, C. 1985. Estudios en el fitoplancton coleccionado durante el crucero Océano IV-área I en el Caribe colombiano. Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Cartagena. 113 p. [ Links ]

Téllez, C., G. Márquez and F. Castillo. 1988. Fitoplancton y ecología pelágica en el archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia: Crucero Océano IV en el Caribe colombiano. Bol. Cient. CIOH, 8: 3-26. [ Links ]

Vargas-Castellanos, J. 2008. Distribución horizontal y vertical de la comunidad fitoplanctónica, alrededor de las islas de Providencia y Santa Catalina, Caribe colombiano (época húmeda de 2005). Marine Biology Thesis, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Santa Marta. 130 p. [ Links ]

Vega-Sequeda, J., C.M. Díaz-Sánchez, K. Gómez-Campo, T. López-Londoño, M. Díaz-Ruíz y D.I. Gómez-López. 2015. Biodiversidad marina en bajo Nuevo, bajo Alicia y banco Serranilla, Reserva de Biosfera Seaflower. Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost., 44(1): 199-244. [ Links ]

Webber, M., E. Edwards-Myers, C. Campbell and D. Webber. 2005. Phytoplankton and zooplankton as indicators of water quality in Discovery Bay, Jamaica. Hydrobiologia, 545: 177-193. [ Links ]

Wickstead. J. 1959. A predatory copepod. J. Anim. Ecol., 28(1): 69-72. [ Links ]

Wüst, G. 1964. On the stratification and the circulation in the Cold Water Sphere of the Antillean-Caribbean Basins. Deep-Sea Res., 10: 165-187. [ Links ]

RECEIVED: 26/03/2014 ACCEPTED:14/09/2015

ANEXOS