INTRODUCTION

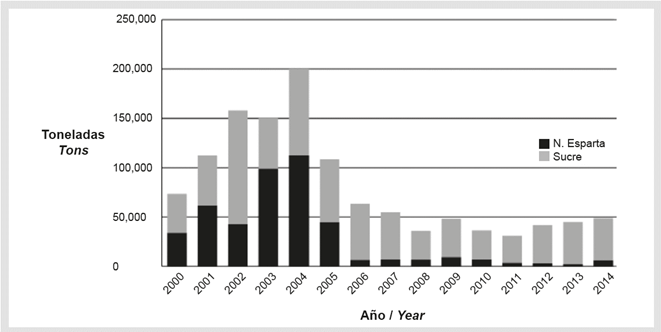

The sardine Sardinella aurita, caught in the states of Sucre and Nueva Esparta, is Venezuela's most important fishery resource. Fishing began in 1927 off the southeast of Margarita Island, and the first canning factory was constructed in 1934 (Gómez et al., 2008); fishing began during 1939 in Sucre (Freón and Mendoza, 2003), and another factory was established. Thirty years later (1956), the first biological data on sardines were collected, with international technical assistance from FAO (Heald and Griffiths, 1967). In 1973, after 46 years of exploitation, the first fishing regulation mandated that caught sardines must have a minimum size of 15 cm in total length (TL) (Gaceta Oficial 30283 of 12/18/1973). This limit remained in place for 33 years. In 2006, the minimum size for capture was increased to 17 cm, exports were banned, equipment was regulated, and a limit of 200,000 tons was established (Gaceta Oficial 38377 of 1/10/2006). This last limitation was not applicable because in 2005, the sardine crisis began (Gómez et al., 2008) and reduced the national catch, which did not surpass 50,000 tons between 2008 and 2014. The catch in Nueva Esparta fell by 90% (Figure 1).

Without specific studies, the crisis was attributed to overexploitation (González et al., 2007) and overfishing (Rueda, 2012; Mendoza, 2015); however, earlier studies had concluded that fishing was underexploited (Guzmán and Gómez, 2000; Freón and Mendoza, 2003; Freon et al., 2003), and hydroacoustic surveys agreed on the availability of 850,000 tons (Gerlotto and Ginés, 1988; Stromme and Saetersdal, 1989; Cárdenas and Achury, 2002) and a total biomass of 1,300,000 tons (Cárdenas, 2003). Despite gaps in official statistics, a record catch (200,000 tons), which was four-fold smaller than the estimated mass available, was obtained in 2004. In contrast, other studies support the belief that the sardine crisis has ecological causes (Gómez, 2006a, 2007; Gómez et al., 2008) tied to a reduction in aquatic fertility (Gómez, 2006b; Gomez et al., 2012, 2014), which results in population fluctuations (Gómez, 2015); this phenomenon is common in small pelagic species and has been documented since the late 19th century in European herring (Hjort, 1914).

In 2013, eight years after the sardine crisis, acting on signs of overexploitation and a reduction in the resource, fishing authorities raised the minimum permitted size for capture to 19 cm and prohibited sardine fishing for three months (Gaceta Oficial 40308 of 4/12/2013), thereby preventing total collapse; these measures are still in place in 2018. Despite these conservation measures, the catches have not recovered, which should have occurred during the early years of their implementation because the sardine reaches recruitment size (100 mm) at six months and sexual maturity at one year of age (Freón et al, 2003; Mendoza et al, 2003). The officially recognized average size of the mature population is 20 cm, but that value is not realistic (Freón and Mendoza, 2003). If this value was correct, the resource would have been exhausted during the last century, as was suggested years ago (FAO, 1979); however, the resource continues to be exploited after 90 years of fishing.

The present article analyzes the management measures implemented by Venezuelan fishery authorities and examines, with regard to overfishing, whether a noticeable change has occurred in the average size of the sardines caught between 2002 and 2016 off Margarita Island. Such change in fish length is a sign of intensive exploitation (Gulland and Rosenberg, 1992), as has been demonstrated for sardines (Kawasaki, 1992; Hiyama et al, 1995; Shin and Rochet, 1998; Voulgaridou y Stergiou, 2003) and employed locally in the 1960s (Simpson et al, 1965; Simpson and Griffiths, 1967). The decision to increase the minimum size for capture to 19 cm and impose a seasonal prohibition on sardine fishing is also examined because the studies on which these actions are based have been questioned, and these actions affect fishermen, processors and consumers. Finally, comments regarding the use of fishing gear and statistics are offered.

STUDY AREA

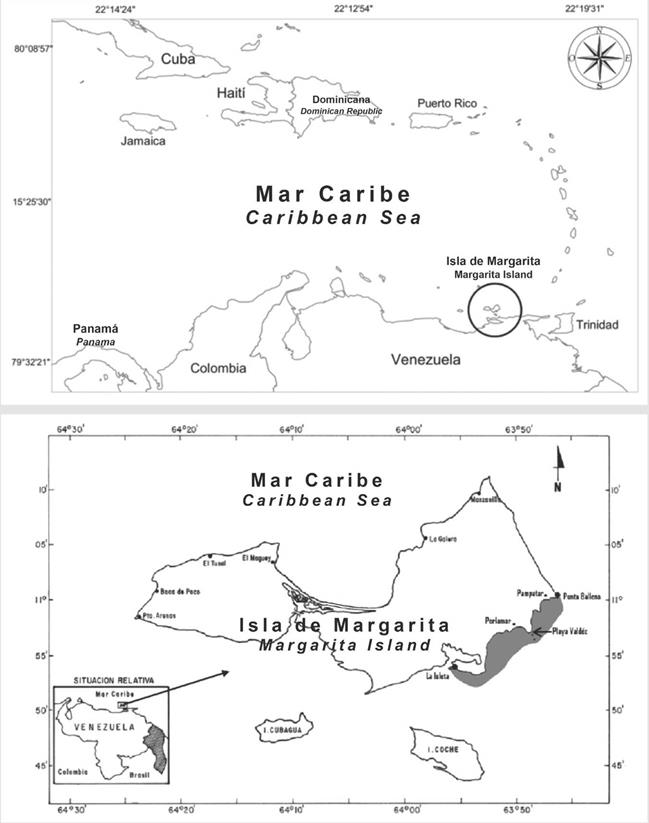

Northeastern Venezuela includes the states of Sucre and Nueva Esparta, the latter composed of Margarita Island, Coche and Cubagua. This region has a moderate marine primary production that yields considerable wealth from fishing (Margalef, 1965), most importantly from the Caribbean Sea (Gómez, 1996; Freón and Mendoza, 2003; Mendoza, 2015). Aquatic fertility depends on several factors, especially the upwelling of subtropical waters as a result of the trade winds. The upwelling varies from year to year with regard to hydrography, nutrients and chlorophyll (Gómez et al., 2014) and is the object of numerous oceanographic studies (Gómez and Barceló, 2014). The productivity of the water affects fishing resources, such as the sardine S. aurita caught in the region, where 90% of the small pelagic species in the Caribbean are also found (Rueda, 2012). For Nueva Esparta, the largest catches are to the southeast of Margarita Island (Figure 2), where approximately 20 artisanal fishing gears named "chinchorros" are active, each with a crew of approximately 20 fishermen. Until 2005, most of the catch was sold to canning factories; actually, much of the catch goes directly to food consumption.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The commercial sardine harvest caught with beach seines to the southeast of Margarita Island was sampled between 2002 and 2013, and a measuring device was used to determine the TL of between 130 and 150 sardines from each catch in millimeters. Measurements taken by the Socialist Institute for Fishing and Aquaculture (Insopesca) from 2014-2016 were used. To determine differences in the average sizes of sardines caught in locations along the Pampatar-La Islet axis and in the state as a whole, multifactorial variance analysis was performed, and to detect changes in the average size over the course of years, regression analysis was performed according to the criteria proposed by Voulgaridou and Stergiou (2003). The Statgraphics program™ was used in this analysis. In all, 209 hauls from sardine fishing boats were analyzed; Table 1 shows the number from each location.

Table 1 Sardine sets studied in locations on Margarita Island, Venezuela (2002-2016). *From Insopesca Nueva Esparta.

| Año Year | Pampatar | Moreno | El Morro | Los Cuartos | La Isleta | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |||

| 2003 | 6 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 38 | |

| 2004 | 14 | 2 | 26 | 5 | 47 | |

| 2005 | 15 | 0 | 17 | 3 | 35 | |

| 2006 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| 2007 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 15 |

| 2008 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| 2009 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| 2010 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| 2011 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 2012 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 2013 | 1 | |||||

| 2014* | 6 | 4 | 10 | |||

| 2015* | 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 | ||

| 2016* | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Total | 83 | 8 | 91 | 14 | 13 | 209 |

RESULTS

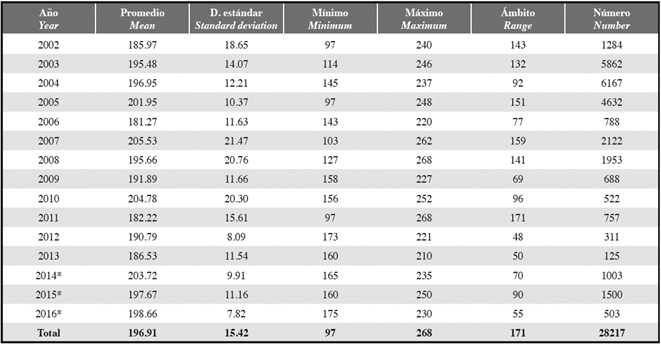

Samples were obtained between 2002 and 2013 from 183 sardine hauls, most of them from Morro de Porlamar and Pampatar, with these two locations accounting for 72% of the fishing grounds studied; 25,086 sardines were measured. Between 2014 and 2016, a total of 3,131 measurements from 26 hauls inspected by government officials were used. In all, 209 hauls were sampled, and 28,217 sardines were measured. Table 2 shows the annual size of the sardines caught between 2002 and 2016.

Table 2 Statistical summary for the size of sardines (TL in mm) from the southeast region of Margarita between 2002 and 2016. *Measurements taken by Insopesca Nueva Esparta.

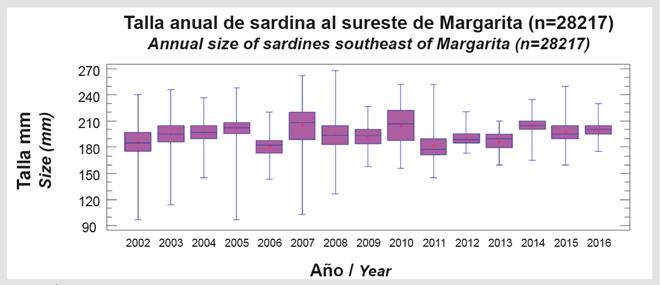

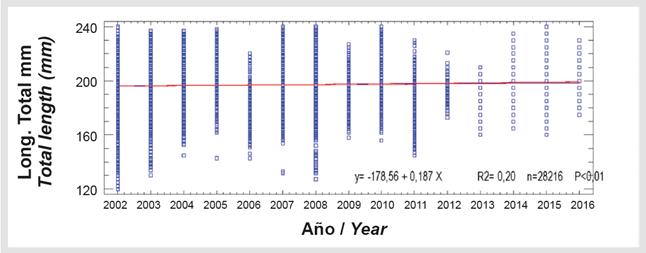

Average size of sardines from the southeast of Margarita: The smallest sardine measured 97 mm in length, and the largest measured 268 mm; the average annual size ranged from 181.27 to 205.53 mm (Figure 3).

When the largest sardine catches occurred in 2003 and 2004, the average sizes (TLs) were 195.48 and 196.95 mm, respectively; these sizes exceeded the average sizes obtained in 2002, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2013 (which ranged from 181.27 to 191.89 mm); the average size was 201.95 mm when the crisis began in 2005, 205.53 mm in 2007 and 204.78 mm in 2010 (Table 2). In 2014, 2015 and 2016, the average sizes were 203.72, 197.67 and 198.66 mm for TL, respectively; these values may be affected by the approximation (0.5 cm) of official easurements. The regression analysis results indicate that the annual average size of captured sardine had significant changes (r = 0.045 n = 28216 p <0.001) with the years towards a larger size but of little magnitude (R2 = 0.20%) and not towards a smaller one (Fig.4).

Figure 4 Mean annual size (TL) in mm of S. aurita sardines caught southeast of Margarita between 2002 and 2016.

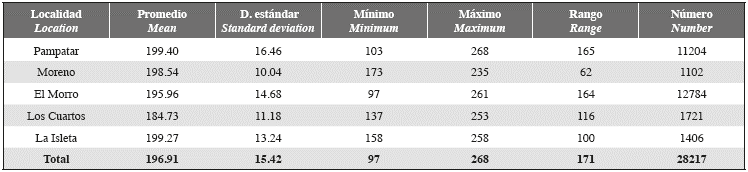

With regard to the sardines caught in various fishing grounds, the average size ranged from 184.73 mm (Los Cuartos) to 199.27 mm (La Isleta), with an overall average of 196.91 mm for the set (Table 3). Significant differences were observed in the size of the sardines caught in the different locations (p < 0.001).

Table 3 Statistical summary of the mean size (TL in mm) of sardines captured in locations of Margarita Island (2002-2016).

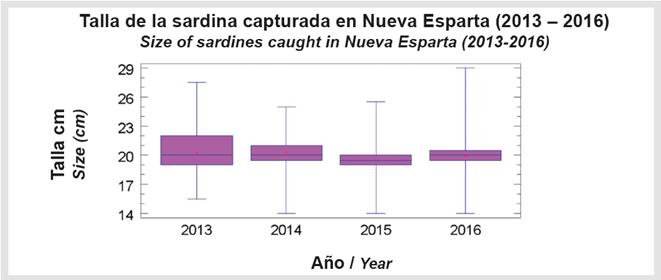

Size of sardines caught in Nueva Esparta (2013-2016): According to official sardine measurements, the average size was 20.3, 20.26, 19.46 and 19.95 cm in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively, yielding an overall average of 19.86 cm (Table 4 and Figure 5). No significant difference was found in the average size over these years (p > 0.05).

Table 4 Summary statistics for size (TL in cm) of sardines sold in Nueva Esparta (2013-2016 taken from Insopesca measurements).

DISCUSSION

In 2003 and 2004, when the largest sardine catches occurred southeast of Margarita Island, the average sizes were 195.48 and 196.95 mm, values which surpassed the average sizes for the previous year (2002) and some subsequent years (2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2013), as shown in Table 2; in 2005, the first year of the sardine crisis, the average size was 201.95 mm. Similarly, the sizes in 2003 and 2004 were slightly smaller than the 2014 average (203.72 mm) and comparable to the official measurements in 2015 and 2016 (197.68 and 198.66 mm) (Table 2). The national catch reached a record high in 2003 and 2004, (Rueda, 2012; Mendoza, 2015), but the average size on Margarita exceeded 19 cm, which proves that no overfishing of sardines occurred, considering that the average size of individual specimens has not diminished. Thus, overexploitation did not occur southeast of Margarita because the size was 201.95 mm at the beginning of the crisis (2005), that is, larger than in 2003 and 2004, when the largest catches occurred.

Fishing is known to affect the age structure and length of resources (Jennings et al, 2001; Jennings and Reynolds, , and a change in fish length is a sign of intense exploitation; therefore, the average size serves to monitor populations, as a steady decline suggests a heightened intensity of fishing (Gulland and Rosenberg, 1992). After a marked increase in the capture of Sardina pilchardus sardines, a decline in the average size was noted (Voulgaridou and Stergiou, 2003); intensive fishing also leads to a reduced length of Japanese sardines (Kawasaki, 1992; Hiyama et al, 1995). To the southeast of Margarita, in the midst of the sardine crisis between 2006 and 2012, the average size (TL) fluctuated between 181.27 and 205.53 mm (Table 2); thus, no marked variation in the average size was observed (Figure 4), and the total average size observed until 2016 was 196.91 mm (Tables 2 and 3). Therefore, there is no basis for the alleged overfishing of this resource by Margarita fishermen, who use the traditional seine nets.

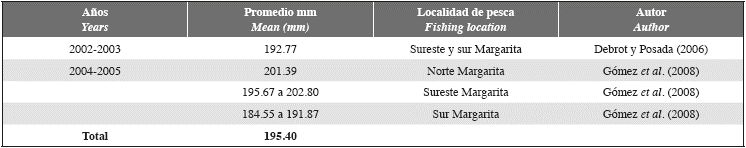

In 2002-2003, the sardines caught in Nueva Esparta ranged in size from 97 to 246 mm (TL) (Debrot and Posada, 2006). In 2004-2005, the average size of the sardines caught to the north of Margarita Island was 201.39 mm; those caught to the southeast ranged in size from 195.67 to 202.80 mm; and those caught to the south of Margarita, Cubagua and Coche ranged in size from 184.55 to 191.87 mm (Gómez et al, XX. Accordingly, between 2002 and 2005, the average size exceeded 195 mm, with no notable decrease during those years (Table 5). Between 2013 and 2016, the official measurements ranged from 140 to 290 mm, averaging between 194.6 and 203.0 mm (198.6 mm overall).

For the period from 1956-1989, the average size ranged from 17.5 to 20.1 cm in Araya, Margarita and Carúpano (Freón et al, 2003); according to our calculations, the annual values for that 33-year period averaged 19.3 cm, which is similar to the value of 19.6 cm obtained in Margarita between 2002 and 2016 (Table 2). Thus, one can conclude that since 1956, the average annual size of sardines caught in this region has shown no notable change, remaining larger than 19 cm, without signs of overfishing according to the criteria used by Gulland and Rosenberg (1992).

However, overfishing (González et al, 2007; Rueda, 2012; Mendoza, 2015) may have occurred in Sucre because fishing intensity affects the size and length structure of schools along the La Esmeralda-Puerto Santo fishing axis, an area very disturbed by sardine fishing gears (Barrios et al. 2010), also known as "machines" operating far from the coast.

Sardines have been fished in Venezuela since 1927, but biological data on the catch size have only been recorded since the 1950s. Data from 1956 to 1973 show that a significant percentage of the catch consisted of sardines measuring less than 170 mm, smaller than the minimum size calculated for earliest maturity (Etchevers, 1974). Between 1964 and 1968, fewer than 5% of the sardines caught to the south of Margarita and Araya measured 190-200 mm (Haugen, 1969); the most common sizes caught in 1997 were 173 mm, 178 mm and 183 mm (Guzmán et al, 1999); and in 1998, the sardines caught in Santa Fe, the Paria Peninsula and Margarita were larger than 190 mm (Guzmán and Gómez, 2000). During 1956-1989, the most common measurement among the sardines caught was 15-16 cm (representing 50% of the total), surpassing the number of sardines measuring 19 and 20 cm (Freón and Mendoza, 2003). This pattern indicates that for more than 30 years, the majority of sardines caught were between 15 and 18 cm in length. In the Gulf of Cariaco during the 1990s, three size groups were observed: < 150 mm (20%), 150-188 mm (60%) and > 198 mm (22%). The most frequently recorded sizes were 163, 168, 173 and 178 mm, with sardines smaller than 180 mm composing 80% of the catches (Guzmán et al, 1998). Note that the data show no decline in the average size of sardines caught since 1957, suggesting that no overfishing occurred (Simpson et al, 1965; Simpson and Griffiths, 1967).

Thus, the bulk of commercial catches since before 1960 has comprised sardines measuring 17-18 cm, indicating that their average size has been less than 19 cm for decades. This reality led to the conclusion that the resource would be exhausted in a few years, specifically in 1993, when no sardines would be available for the canning factories (FAO, 1979). This depletion theory was surely the result of studies that identified 195 mm as the average size at maturity (FAO, 1963; Huq, 2003) and the belief that the sardine catch consisted largely of preadults that had not yet reproduced. Fishing sardines that had not yet reproduced would obviously lead to an imminent total collapse of the population; therefore, the average length at maturity (Lm50%) has been considered to be 20 cm since the 1960s. Twenty-five years after the exhaustion prediction, a record catch of 200,000 tons was recorded in 2004. This record catch indicates that after 80 years of cannery operation, sardines had not been exhausted, nor did they show signs of overfishing, as no notable reduction occurred in the size of the sardines caught, as least to the southeast of Margarita Island and in Nueva Esparta. Similarly, until 2013, studies found that the average size of the sardines caught was less than 20 cm but larger than the 17 cm limit imposed by the 2006 regulation. One may therefore reason that if 20 cm is truly the average size at which sardines reproduce (Lm50%), as various studies have concluded and remarked, then the fact that the bulk of sardines caught since 1950 measured less than 20 cm indicates that the resource should have been exhausted some decades ago.

Analysis of size at maturity and the seasonal prohibition on sardine fishing

The minimum size is determined by sex via direct observation of the gonads, whereas the size at which 50% of the population is mature (Lm50%) is determined by the size of the smallest mature specimen, based on which size intervals (510 mm) are set, calculating its relative frequency and the total number of mature specimens.

Minimum size at maturity: The first available studies found mature specimens measuring 134 mm (Simpson and González, 1967), but 115 mm has been mentioned (D'Souze, 1981); other studies report a minimum size at maturity of 152 and 150 mm (Guzmán et al, 1999; Freón and Mendoza, 2003). On Margarita Island, mature males and females measuring 136 and 141 mm have been found (Kortnik, 2005), with maturity at sizes between 14.4 and 16.7 mm also reported (Mendialdúa, 2004; Gassman, 2005; Tagliafico, 2005).

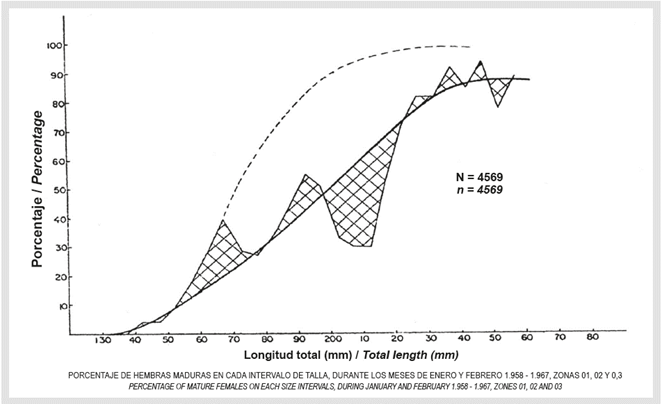

Average length at maturity (Lm50%): Based on samples taken at Sucre, the conclusion was reached that mean maturity occurs at a TL of 195 mm (FAO, 1963); maturity was estimated to occur at 169 mm in the 1980s (Ramírez and Huq, 1986) and at 198 mm in the 1990s (Guzman et al., 1998). Etchevers (1974) developed a graph of mature females according to size (Figure 6) and explained the discontinuity as the product of poor sampling or a heterogeneous makeup of two groups of sardines: one between 167 and 193 mm in size and the other between 177 and 210 mm. Etchevers concluded that the Lm50% of the population occurs between 170 and 200 mm but fluctuates in some years approximately 170 mm, when 40% of the females are mature at 170 mm, and 65% are mature at 180 mm; thus, most mature sardines measure 17-18 cm.

Similarly, Haugen (1969) found spawned females under 18 cm in size to be abundant. Other studies found annual Lm50% values varying between a TL of 166 and 247 mm (Huq and Rodríguez, 1988) and measuring 195 mm TL (Guzmán et al., 1999; Guzmán and Gómez, 2000). Based on samples taken between 1956 and 1989, the Lm50% value was estimated at 19.7 cm (20 cm) (Freón and Mendoza, 2003; Freón et al., 2003).

Figure 6 Mean length at maturity (Lm50%) of mature females caught between 1958 and 1967 (SourceEtchevers, 1974).

Some studies have found that to the southeast of Margarita Island, the average size at maturity ranges between 19.83 and 20 cm (Mendialdúa, 2004; Gassman, 2005; Tagliafico, 2005), but more than 75% of the samples consisted of individuals who had already reached maturity (Tagliafico et al., 2008). However, another study conducted at the same time as those mentioned found that Lm50% occurs at a standard length (SL) between 158 and 162 mm, so a TL of 17 cm (equivalent to a SL of 166 mm) ensures that sardines are able to reproduce before their capture (Kortnik, 2005; Kortnik and Posada, 2006), in line with the official provision of 2006 determining a minimum catch size of 17 cm. The notable difference in the Lm50% of the latter study can be explained by the approach taken, as most other studies sampled specimens of the relatively common larger sizes and ignored the smaller sizes. Therefore, if the sardines analyzed were those that had already reached sexual maturity, the Lm50% would be biased by studying mostly larger sardines that had not experienced their first spawning.

The true Lm50% is obtained when sardines of other sizes are equally represented in the study, which is accomplished by observing a similar number of specimens from each size category. Thus, in a study that found a smaller size of maturity, an equal number of sardines from three size groups were analyzed: small specimens < 14 cm, medium specimens between 14 and 17 cm and large specimens > 17 cm (Museo Marino de Margarita, 2003); the resulting Lm50% was less than 17 cm TL (Kortnik, 2005; Kortnik and Posada, 2016), a lower value than the 20 cm TL size found by other studies in the same area. Therefore, suggestions were made to raise the minimum size of capture to this length (Tagliafico et al, 2008) and prohibit fishing during the first quarter of the year to aid population recovery (Gassman et al, 2012).

Additionally, the Lm50% of S. aurita sardines is reached in West Africa (Ghana) at a TL of 16.7 cm for males and 17.1 cm for females (Quaatey and Maravelius, 1999); the TL value was 14.3 cm in the Mediterranean Sea (Tunisia) (Gaamour et al, 2004), 15.5 cm for males and 16.8 cm for females in the Aegean Sea (Tsikliras and Antonopoulou, 2006) and ranged from 15.8 to 16.6 cm in the Adriatic Sea (Mustac and Sinovcic, 2012). These results are similar to those found for Margarita (Kortnik, 2005); an Lm50% value < 17 cm TL for S. aurita sardines of the eastern Atlantic Ocean and Venezuelan waters (Table 6) is explained by a relatively strong genetic relationship among the populations (De Donato et al, 2005), despite their geographical differences.

In Venezuela, the studies reporting an average sardine length at maturity of 20 cm are equally flawed, in that these studies used specimens that had reached maturity (Tagliafico et al, 2008) and examined few medium and small-sized sardines, causing a marked bias in sampling. This situation was noted by Freon et al, (2003): "the greatest limitation of our analysis lies in the unbalanced nature of the sample design and the use of commercially caught sardines, which underrepresents specimens of smaller sizes". Note also that "conflicting results reflect differences in how authors define sexual maturity" (Huq, 2003) and that a lack of practical experience occurs in several studies.

A TL of 20 cm is accepted as the Lm50% of sardines but is not considered real because its use would prohibit fishing in several areas and reduce catches to the north of these areas (Freón and Mendoza, 2003). Furthermore, its implementation would practically prohibit exploiting this resource in Venezuela because the annual average length of the catch to the southeast of Margarita during 2002-2013 and the average sizes caught during 2013-2016 in Nueva Esparta (Tables 2 and 3) are less than 20 cm. Moreover, were the sardine Lm50% value actually near 20 cm, this fishery resource would have been exhausted in the previous century, as was previously suggested (FAO, 1979). However, sardines are still exploited after 90 years of fishing because the true size at reproduction is < 17 cm according to certain studies (Table 6). The sardine crisis is a result of natural population fluctuation caused by ecological changes that reduce fertility, affecting the abundance of marine and fishing resources such as sardines (Gómez, 2015).

Table 6 Average length at maturity (Lm50%) of S. aurita for Venezuela, West Africa (Ghana) and the Mediterranean Sea. (TL, SL and FL = total length, standard length and fork length).

Minimum catch size (19 cm TL) and fishing prohibition: The official regulation in force since 2013 prompts the obvious question of why the fishery authorities set the sardine catch size at 19 instead of 20 cm TL, which is the Lm50% value for that population, according to several authors? (Table 6). Imposing the smaller capture size of 19 cm makes no sense with an Lm50% of 20 cm because this action would allow sardines that have not spawned to be caught. However, this action may also indicate the fishery authorities lack confidence in the research. The goal of science is to search for the truth; by this standard, the studies concluding that the average size of sardines at maturity is 20 cm fall short due to sampling flaws. The difference between 17 and 20 cm is slight but has significant implications because sardines smaller than 20 cm compose the bulk of the catch, and prohibiting their capture affects fishermen, the canning industry and broad sectors of the Venezuelan population that consume large volumes of fresh sardines due to their low cost. Inappropriate regulation disproportionately affects the consumption of animal protein by the neediest sectors of the population with the least purchasing power.

Prohibition: The current official provision prohibits sardine fishing during the first three months of the year, supposedly to protect the species during its breeding period. However, an 11-year study on the abundance of sardine eggs in plankton finds the lowest egg abundance during the months of January-March, with the ecological explanation that sardine reproduction is less intensive during this period (Gómez, 2015). The current prohibition affects producers, processors and consumers when the catches are abundant. The regulation should be applied during the months showing the greatest abundance of eggs in the plankton, which occurs during the last quarter of the year (Gómez, 2015).

Commentary on fishing gear and statistics

Fishing gear: Seine nets (chinchorro) 1500 m in length have been used in Margarita since 1850 (Level, 1942) and have been employed to fish for sardines since 1927. In 1960, this method was described as primitive but efficient (Griffiths and Simpson, 1967); changes subsequently occurred during the 1960s in the number of operating nets (from 18 to 194), their length (160-270 to 900 m), the method of hauling them (manual to motorized) and the distance off the coast of the sites where the nets were used (up to 2.5 km from the beach). Fishing was said to depend on random luck to bring sardine schools toward the coast, requiring a change in methods to increase catches (Etchevers, 1974). Attempts to effect this increase used enclosures (artisanal purse seines), with modest results (Griffiths and Simpson, 1967). In Sucre, many producers have used gear called "machine" (artisanal purse seine) in areas far from the coast since the 1980s. This fishing gear is intensively used; between La Esmeralda and Puerto Santo, the number is known to have grown from 52 in 1996 (Barrios et al. 2010) to 100 in 2014, (Gaceta Oficial 40573 of January 2015), but the actual number is higher.

On Margarita Island, the fishermen only use the "chinchorros" less than a mile from the beach, and its features and operation have been described (Gómez and Gonzalez, 2008). The use of this fishing gear is a fairly nonaggressive method, in that the nets are cast into the water when schools approach the coast and brought in close to the beach and anchored after the sardines are caught, so the catch remains alive but confined in the nets. This method allows the fishing authorities to determine the size of the sardines caught and either authorize their sale or order their release. This process is impossible with the use of "machines" (artisanal purse seines) because the sardines die immediately, increasing the difficulty of monitoring in deep waters; monitoring can be performed once the catch is moved to the beach, but prior selection is not possible.

The "machine" activity can have negative effects on the sardines because fishermen seek out the schools in deep waters and surround them with nets that reach 400 m in length and a depth of 40 m (Gaceta Oficial 40308 of December 2013). In other words, these nets reach the bottom along the whole northeastern offshore shelf of Venezuela, specifically on the Los Testigos shelf, which is 95 km long, 40 km wide, reaches depths of 37 m (Maloney, 1971) and constitutes the largest continental terrace of the South Caribbean. Once caught, sardines die within a few minutes, and the majority are possibly juveniles or recruits recently incorporated into the pelagic environment that has started to be actively exploited (Gómez, 2015). The intensive use of "machines" (artisanal purse seines) should be reviewed by the fishing authorities, prioritizing "on-site" investigations along with fishermen to determine the true circumstances of this fishing method.

Statistics: The figures for Venezuelan sardine fishing are unreliable. Between 1966 and 1975, based on the production of meal and canned sardines, these figures were calculated to be underestimated by 31%, recording fewer sardines than were landed, and show a discrepancy between 2% and 85% with the figures declared annually by the industry (Trujillo, 1977), causing variations from year to year (Nascimento and Rojas, 1971). This situation remained unchanged between 1973 and 1989 (Guzmán et al, 2003), and the size of the underestimation may have grown during the 1990s. The annual catch has been reported to have grown cyclically by 27,000 tons since 1957 and to have shown ups and downs, declining to 23,400 tons in 1961 and rising to 43,800 tons in 1965 and to 46,700 tons in 1973. Between 1979 and 1989, these catches fluctuated between 16,000 and 80,000 tons (averaging 40,000 tons), with large variations (Guzmán et al., 2003). The catches were 150,000 tons in 1990-1991 but declined to 65,000 tons in 1996, reached 000 tons in 1998 and shrunk to 73,000 tons in 2000. After 2001, the catches grew to reach a record of 200,000 tons in 2004. The crisis started in 2005, and the catch fell to 36,000 tons in 2008 and did not surpass 50,000 tons until 2014.

However, many of these figures are inaccurate, as research has shown that fewer sardines are recorded than are landed at the factories (Trujillo, 1977). This means that the sardine industry supplied the government with catch figures based on sardines bought from fishermen. However, industries also produce fish meal with the byproducts of processing (head, gills, scales, tails and viscera) and with Cetengraulis edentulus and Anchoa spp. anchovies, which have been virtually exhausted; the clupeid Opisthonema oglinum has also been used to produce fish meal (Simpson and Griffiths, 1967). Due to the sardine crisis and the current importance of fresh sardine consumption, the proper implementation of the official regulations established in 1998, which state that fish meal should come from the milling of sardine byproducts that are unfit for consumption, is crucial to maintain and monitor.

Sardine catches are underestimated (Mendoza, 2003) due to shortcomings in data collection, producing unreliable statistics (Guzmán et al, 2003) that are applied to the artisanal fisheries of Venezuela and report a fraction of landings (Novoa et al, 1998). For example, in Nueva Esparta, official figures mention a catch of 21,000 and 16,000 tons in 2006 and 2007; however, records obtained directly from producers show that the catches were really 42,342 and 36,142 tons (Marval and Cervigón, 2008) and mention that "official data are not used because they are highly inaccurate and make no distinction among species". Between 1950 and 2010, the catches of Venezuelan artisanal fisheries were estimated at 13,212,000 tons, but 29.3% were not reported (Mendoza, 2015).

A significant portion of the national sardine catch comes from Nueva Esparta, but the real catch figures are unknown before 2002 because the estimates were submitted by factories, mostly located in Sucre, and the landings were incorrectly assigned. Thus, according to official figures, the catches in Nueva Esparta were 49,809, 1155 and 31,112 tons in 2000, 2001 and 2002, respectively, but the producers claimed very different figures. Therefore, a project was implemented to determine the actual catches, and the fishermen were correct: southeast of Margarita alone, the sardine catch totaled 63,732 tons from August 2002 to September 2003 and 72,141 and 24,459 tons (Gómez, 2006 b) in 2004 and 2005, respectively, serving as an example of the disparity between official figures and the reality of sardine fishing, which could easily be reduced through collaboration with the fishermen. In Sucre, correct figures for the catches brought by "machines" are vital because no decision on the management of Venezuela's main resource will be made on a firm foundation without accurate knowledge of the true numbers.

Soon after the onset of the sardine crisis, opinions were floated attributing the resource reductions to overfishing. Rather than blaming the fishermen, attention should be given to possible causes intrinsic to the population and to a numerical reduction in sardine eggs and larvae, as studies have found, as well as to possible global-scale causes.

CONCLUSIONS

To the southeast of Margarita Island, in no year between 2002 and 2013 was a notable reduction recorded in the average size of the sardines caught. In 2003 and 2004, the sizes averaged 195.48 and 196.95 mm TL, respectively, surpassing the sizes for 2002, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2013. When the crisis began in 2005, the sardine size was 201.95 mm. Following maximal catches of sardines in 2003 and 2004, no reduction in their average size was observed, which suggests that overfishing did not occur.

The studies concluding that the mean size of maturity for sardines is 20 cm TL are flawed, due to their reliance on sampling with a pronounced bias. The true Lm50% of S. aurita is < 17 cm, as studies in the eastern Atlantic Ocean and Venezuela have concluded.

The ban on sardine fishing from January to March is unwarranted because sardine eggs show relatively low abundance in the plankton during that time, according to an 11-year study on Margarita Island.

The intensive use of a fishing gear known as the "machine" (artisanal purse seine) may have negative effects on the sardine population.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Venezuelan fishing authorities should reconsider not only the sardine fishery management measures related to the minimum permissible size but also the seasonal ban on sardine fishing. These regulatory changes should additionally be complemented with ongoing environmental studies and frequent reassessments, as performed with small pelagic species in other latitudes. Investigating the reality of sardine fishing with the fishing gear known as the "machine" (artisanal purse seine fishing) should be a priority.

text in

text in