Notes

Collecting device for zooplankton associated with mesophotic coral ecosystems

1Grupo de investigación Biología Descriptiva y Aplicada, programa de Biología, Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia.

2Grupo de investigación Biología Descriptiva y Aplicada, programa de Biología, Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia. hhenaoc@unicartagena.edu.co

3Grupo de investigación Hidrobiología, programa de Biología, Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia. gnavass@unicartagena.edu.co

4Grupo de Estudios e Investigaciones Ambientales, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. mcriales@uis.edu.co

5Parque Nacional Natural Corales de Profundidad, Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia, Cartagena, Colombia. milena.marrugo@parquesnacionales.gov.co

ABSTRACT

Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) host unique communities that have not been sufficiently studied due to the high cost of available technologies. These reefs can be found between 30 and 150 m deep, where the amount of incident light is < 10 % of that reaching the surface. The zooxanthellae associated with these reefs have a reduced photosynthetic rate due to the low availability of light, therefore, zooplankton becomes the main food source for the coral colonies. To study the composition of zooplankton communities associated to these ecosystems, a device that allowed the collection of zooplankton present on the Bajo Fríjol reef scaffold was designed and tested in the Corales de Profundidad National Natural Park. The device consisted of a weighted hose that reached the desired depth, connected to the collecting device, by means of which the water was filtered using a suction pump. The amount of filtered water, the species collected, and their abundance allowed to conclude that the device is a useful, versatile and economic tool for the characterization and monitoring of the zooplanktonic community in the Corales de Profundidad Park, so it could be extended to other shallow and mesophotic coral ecosystems.

KEYWORDS: mesophotic reefs; collection device; zooplankton

RESUMEN

Los ecosistemas de corales mesofóticos (MCEs) albergan comunidades únicas que no han sido suficientemente estudiadas debido al alto costo de las tecnologías disponibles. Estos arrecifes pueden encontrarse entre 30 y 150 m de profundidad, donde la cantidad de luz incidente es < 10 % de la que llega a la superficie. Las zooxantelas asociadas a estos arrecifes tienen una tasa fotosintética reducida debido a la baja disponibilidad de luz, por lo que el zooplancton se convierte en la principal fuente de alimento para las colonias de coral. Para el estudio de la composición de las comunidades zooplanctónicas asociadas a estos ecosistemas, se diseñó y probó un dispositivo que permitió la recolección de zoopláncteres presentes sobre el andamio arrecifal de Bajo Fríjol, en el Parque Nacional Natural Corales de Profundidad. El dispositivo consistió en una manguera lastrada que llegaba a la profundidad deseada, conectada al dispositivo recolector, mediante el cual se filtraba el agua gracias a una bomba de succión. La cantidad de agua filtrada, las especies recolectadas y su abundancia permitieron concluir que el dispositivo es una herramienta útil, versátil y económica para la caracterización y el monitoreo de la comunidad zooplanctónica en el Parque Corales de Profundidad, por lo que podría extenderse a otros ecosistemas de arrecifes someros y mesofóticos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: arrecifes mesofóticos; dispositivo de recolección; zooplancton

Mesophotic corals (MCEs) are calcareous structures that usually grow from 30 m depth to the euphotic zone limit (Slattery and Lesser, 2012; Kahng et al., 2014; Laverick et al., 2017). At these depths, the low photosynthetically active radiation available for the zooxanthellae cause a reduction in the calcification rate, so the coral species change their trophic strategy, surviving by feeding on zooplankton (Lesser et al., 2009; Bessell-Browne et al., 2014; Nir et al., 2014). Hence, studying these organisms is essential to understand the ecological processes that allow such unique environments.

Most of the reports regarding the structure of communities in MCEs have focused on sessile organisms such as scleractinian corals, octocorals, and sponges, and mobile organisms such as fish (Kahng et al., 2014; Scott and Pawlik, 2019), leaving aside the zooplanktonic communities, due to the high costs of the available technologies (Enrichetti et al., 2019), and the difficulties of zooplankton sampling in these environments. Therefore, the purpose of this work was to design and test a suction device that would allow the collection of water on the reef substrate, to study the zooplankton community associated with MCEs in Bajo Fríjol, Corales de Profundidad National Natural Park (PNNCPR).

The device was built based on the pumping system, which allows the sampling aboard the ship, filtering a known volume through one or more nets, of the same or different mesh size (Jacobs and Grant, 1978). This system also allows working at specific depths and avoids contamination of the sample (Sameoto et al., 2000).

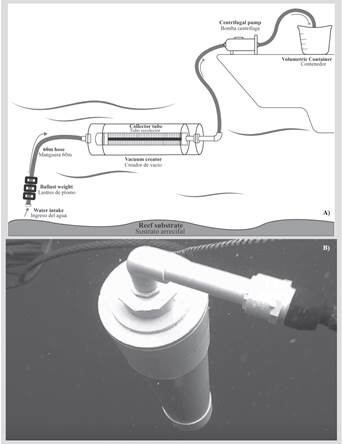

The design consisted of 60 m long and 1.27 cm in diameter gardening hose, marked every two meters, with four ballast weights (2 kg) tied to the lower end to facilitate its immersion and arrival at the reef (Figure 1A). This allowed to collect water samples on the reef substrate, guaranteeing that the zooplankton collected corresponded to that available for feeding the polyps.

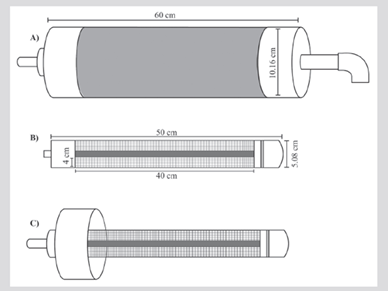

The hose was connected to a vacuum creating tube with 10.16 cm diameter and 60 cm length, made with standard type PVC pipes (Figures 1 and 2A), which carried inside the collector tube (5.08 cm diameter and 50 cm length). It has window-like spaces 4 cm wide and 40 cm long, covered with a net (45 μm mesh size) to retain the organisms (Figure 2B). The vacuum creating tube continued in a short hose connected to a 12 v electric centrifugal pump that suctioned the sea water. Another hose that reached a graduated plastic container, used to estimate the amount of filtered water, on the other side of the pump (Figure 1A).

The device was tested on a first sampling campaign in August of 2016 at the center of Bajo Fríjol, collecting four samples, each with a different filtered volume: 24 L, 48 L, 72 L and 100 L. For each sample, the count and taxonomic identification of the organisms were carried out to the lowest possible category. With this information, an accumulated diversity curve (Shannon index) was elaborated to determine if the maximum available information was reached. Additionally, a species accumulation curve (Magurran, 2004) was elaborated with non-parametric estimators (Chao 2, JackKnife 1 and Bootstrap) to estimate the species richness as a function of sampling effort and a completeness analysis (JackKnife 1). The integrated analysis of these estimators allowed to obtain a better interpretation of the sampling representativity (Moreno, 2001), and estimate the minimum volume necessary to characterize the community. To calculate this index and estimators, the program EstimateS v. 9.1. was used (Villareal et al., 2004; Bautista-Hernández et al., 2013).

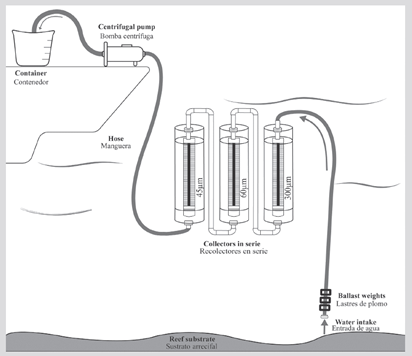

This initial design can be modified depending on the research question. One of these is installing devices in series, with collectors of different mesh sizes (e.g. 45, 60 and 300 µm) that allow retaining representatives of the different sizes of zooplankton (Figure 3). This adaptation was tested in a second sampling campaign in June of 2019, filtering 600 L per sample in the six monitoring stations established by the PNNCPR at Bajo Fríjol. As in the first campaign, the organisms were counted and taxonomically identified (down to the lowest possible category) per collector. The evaluation of both designs was carried out to determine the device effectivity, therefore, other parameters such as spatial and temporal variability were not considered.

For device with a single collector tube, 100 morphospecies were identified, grouped into 16 zooplanktonic groups: appendicularians, bryozoans, cnidarians larvae, crustaceans, doliolids, echinoderms, fish eggs, foraminifera, hydrozoans, mollusks, nemerteans, polychaetes, radiolarians, rotifers, siphonophores and tintinnids. Radiolarians had the highest richness with 27 species, followed by crustaceans with 23. On the other hand, a total density of 90377 ind/m3 was obtained. Crustaceans had the highest density (39980 ind/m3), followed by foraminifera with 17577 ind/m3. Appendicularians, polychaetes, foraminiferans, crustaceans, and tintinnids were present in all filtered volumes. The highest number of morphospecies and the highest density was reached with 72 L.

The accumulated diversity curve (Figure 4A), allowed to conclude that the greatest amount of information is reached after 24 L. The species accumulation curve (Figure 4B), showed inflection at 72 L for most estimators. With the above, it can be inferred that the sampling is representative of the studied community from 72 L, so it is recommended to filter, at least, this volume for zooplankton studies with this device. The completeness analysis showed 90 % with the estimator JackKnife 1, indicating that the collected data were representative.

For the modified device, 24 morphospecies were identified with the 45 µm collector, 94 with the 60 µm collector and 57 with the 300 µm collector, for a total of 174 morphospecies grouped into 16 main groups: appendicularians, bryozoa, crustaceans, cnidarians, foraminiferans, hydrozoa, fish larvae, echinoderm larvae, mollusks, nemerteans, polychaetes, radiolarian, rotifers, siphonophores, thaliaceans and tintinnids. The total densities obtained were 19197 ind/m3 (45 µm), 196915 ind/m3 (60 µm) and 280 ind/ m3 (300 µm). Crustaceans reached the highest abundances with 8678, 91 951 and 151 ind/m3 (45, 60 and 300 µm, respectively), followed by tintinnids with 5342 (45 µm) and 61 271 ind/m3 (60 µm) and radiolarians with 4843, 33189 and 2 ind/m3 (45, 60 and 300 µm, respectively).

A greater richness and abundance were obtained with the 45 and 60 µm collectors. In coral environments, zooplankton comprises organisms of different sizes, but those between 20 and 200 µm, corresponding to microzooplankton, are more abundant (Lalli et al., 1997). In the case of the 300 µm collector, the low richness and abundance can be explained because larger organisms tend to escape more easily from the suction of the hose onto the reef substrate (Boltovskoy, 1981; Sameoto et al., 2000; Baez-Polo, 2013).

This device’s main advantages are low operating costs, easy manufacturing and transportation, proving to be very useful in a state entity, where economic resources are generally limited. This device has become an excellent opportunity for the PNNCPR to start the implementation of its monitoring program in mesophotic zones in an area that, due to its location, depth scope and conservation objective, field operations and samplings imply a high investment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript is product of the project entitled “Preliminary study of the planktonic and benthic communities of the mesophotic reef of Bajo Fríjol at the PNNCPR” endorsed by National Natural Parks of Colombia (memorandum 20152200002063 11-25-15), supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of the University of Cartagena, through the plan de fortalecimiento act 024-2019 and the project 2420 of the Research and Extension Vice-chancellor of the Industrial University of Santander entitled: “Study of the zooplankton community and molecular characterization of phytoplankton in coral reef ecosystems mesophotics of the PNNCPR, Colombian Caribbean”. Authors thank to the personnel of the PNNCPR for their technical support during the manufacture of the collection devices and during the samplings. To Deibis Seguro and Juan Vega for the technical support and the photographs in the field. To the engineer Fabián del Valle, for the graphic design and the illustrations of the device. To the editor and evaluator for reviewing the manuscript.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA/LITERATURE CITED

Baéz-Polo, A. 2013. Manual de métodos de ecosistemas marinos y costeros con miras a establecer impactos ambientales. Convenio para establecer el fortalecimiento de los métodos de investigación marina para actividades costa afuera por parte del sector de hidrocarburos. Invemar/ANH, Santa Marta. 212 p.

[ Links ]

Bautista-Hernández, C.E., S., Monks y G., Pulido-Flores. 2013. Los parásitos y el estudio de su diversidad: un enfoque sobre los estimadores de la riqueza de especies. En: Pulido-Flores, G y S., Monks (Eds). 2013. Estudios científicos del estado de Hidalgo y zonas aledañas, II. Zea Books, Lincoln. 146 p.

[ Links ]

Bessell-Browne, P., M., Stat., D., Thomson, and P. ,Clode. 2014. Coscinaraea marshae corals that have survived prolonged bleaching exhibit signs of increased heterotrophic feeding. Coral Reefs, 33(3): 795-804.

[ Links ]

Boltovskoy, D. 1981. Atlas del zooplancton del Atlántico sudoccidental y métodos de trabajo con el zooplancton marino. Inidep, Mar del Plata. 929 p.

[ Links ]

Enrichetti, F., M., Bo, C., Morri, M., Montefalcone, M. ,Toma, G., Bavestrello, L. ,Tunesi, S., Canese, M., Giusti, E., Salvati, R., Bertolotto, and C. ,Biachi. 2019. Assessing the environmental status of temperate mesophotic reefs: a new integrated methodological approach. Ecol. Indic., 102: 218-229.

[ Links ]

Jacobs, F and C. ,Grant. 1978. Guidelines for zooplankton sampling in quantitative baseline and monitoring programs. VA Inst. Mar. Sci., Corvallis. 61 p.

[ Links ]

Kahng, S., J., Copus, and D., Wagner. 2014. Recent advances in the ecology of mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs). Curr. Opin. Env. Sust., 7: 72-81.

[ Links ]

Lalli, C. and R. ,Parsons. 1997. Biological oceanography: an introduction. 2nd ed. Elsevier, Oxford. 315 p.

[ Links ]

Laverick, J., D., Andradi-Brown, and A., Rogers. 2017. Using light-dependent scleractinia to define the upper boundary of mesophotic coral ecosystems on the reefs of Utila, Honduras. PLoS ONE, 12(8): e0183075.

[ Links ]

Lesser, M., M., Slattery, and J., Leichter. 2009. Ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 375: 1-8.

[ Links ]

Magurran, A.E. 2004. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Science, Oxford. 261 p.

[ Links ]

Moreno, C.E. 2001. Métodos para medir la biodiversidad. Manuales y Tesis SEA. Zaragoza. 84 p.

[ Links ]

Nir, O., D., Gruber, E. ,Shemesh, E., Glasser, and D. ,Tchernov. 2014. Seasonal mesophotic coral bleaching of Stylophora pistillatain the Northern Red Sea. PLoS One, 9(1): e84968.

[ Links ]

Sameoto, D., P., Wiebe, J., Runge, L., Postel, J., Dunn, C., Miller, and S., Coombs. 2000. Chapter 3: collecting zooplankton. 55-81. In: Harris, R., P., Wiebe, J., Lenz, H. ,Skjoldal, and M., Huntleu. (Eds). ICES Zooplankton Methodology Manual. Elsevier, London. 684 p.

[ Links ]

Scott, A. and J., Pawlik, 2019. A review of the sponge increase hypothesis for Caribbean mesophotic reefs. Mar. Biodivers., 49: 1073-1083.

[ Links ]

Slattery, M. and M., Lesser, 2012. Mesophotic coral reefs: a global model of community structure and function. Proc. 12th Internat. Coral Reef Symp., Cairns, Australia.

[ Links ]

Villareal, H., M., Álvarez, S., Córdoba, F., Escobar, G., Fagua, F., Gast, H., Mendoza, M., Ospina y A.M., Umaña. 2004. Manual de métodos para el desarrollo de inventarios de biodiversidad. Programa de inventarios de biodiversidad. Inst. Invest. Rec. Biol. Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá. 236 p.

[ Links ]

text in

text in