Hydrological rehabilitation (HR) is an ecological restoration technique that aims to repair the processes and functionality of hydrology in ecosystems where its alteration has caused degradation (Lewis, 2005). Different authors have implemented this technique in Central American and Colombian mangroves (Sánchez-Páez et al., 2004; Teutli and Herrera, 2016).

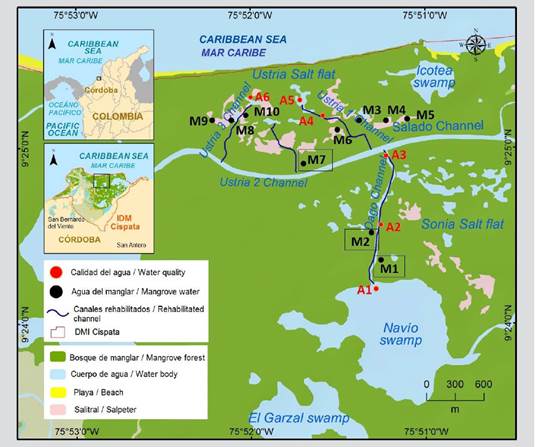

The Cispata Integrated Management District (DMI Cispata) is a protected area of ~ 27 171 ha on the Colombian Caribbean coast, where some mangrove areas, such as the Dago-Ustria sector (Figure 1), have deteriorated due to the clogging of channels, interruption of water flows, and salt crust formation, which affect water quality (CVS and Invemar, 2010; Invemar, 2017). In 2019, environmental institutions and the local community rehabilitated 3267 m of clogged/plugged channels to restore hydrological connectivity (Invemar, 2017).

Figure 1 Study area. Red (A1-A6) and black (M1-M10) points are the water quality stations in channels and swamps and within mangroves. Stations M1, M2, and M7 are in preserved mangroves used as a reference.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the short-term responses (< six months) of the water physicochemical parameters in the rehabilitated channels and within the mangrove forests in the Dago-Ustria sector. Species Rhizophora mangle, Avicennia germinans, and Laguncularia racemosa make up the mangrove forest in Dago sector (Rojas-Aguirre et al., 2018). The climate is tropical rainy savanna with a dry season; multiannual averages (1981-2010) of precipitation range between 1000-1500 mm (heavier rainfall in May and September), temperature between 26-28 °C, relative humidity between 80-85 %, and evapotranspiration between 1200-1400 mm (IDEAM, 2014a, 2014b).

The hydrological dynamics are modulated by the flows of the Sinú River (regulated since 1999 by Urrá I hydroelectric dam), the rainy seasons and the action of the Caribbean Sea (Ruíz-Ochoa et al., 2008). Historically, the Sinú River has formed the deltas Venados (before 1762), Mestizos (1762-1849), Cispata (1849-1938), and Tinajones (1938-present) (Serrano, 2004; Ramos et al., 2015). In the DMI Cispata, low waters (January-May) and high waters (June-December) correspond to a decrease or increase in the flow of the Sinú River with respect to the annual average (389 m3/S), lagging by one or two months from the dry and rainy seasons (Ramos et al., 2015).

Considering the above, the samplings were carried out in September 2018 (before HR, rainy season), March 2019 (before HR, dry season), June 2019 (after two months of HR, dry season), and September 2019 (after five months of HR, rainy season). From August 2018 to July 2019, Niño conditions were present, the condition were normal from August to December 2019 (NOAA, 2020).

In April 2019, the HR of the Dago (1500 m), Ustria-1 (602 m), Ustria-2 (700 m), and Ustria-3 (465 m) channels were carried out (Figure 1), using machetes, axes, and shovels removing plant material and sediment up to 1 m deep and at least 1 m wide (Figure 2). In the Ustria-1 and Ustria-3 channels, we made two secondary channels of 40 m long, 50 cm deep, and 1 m wide, to enable water to flow into the salt planes (Figure 1).

Figure 2 Rehabilitation of the Dago a) and Ustria-1 b) channels in the DMI Cispata. Photos: ASOMAPESCA and Invemar.

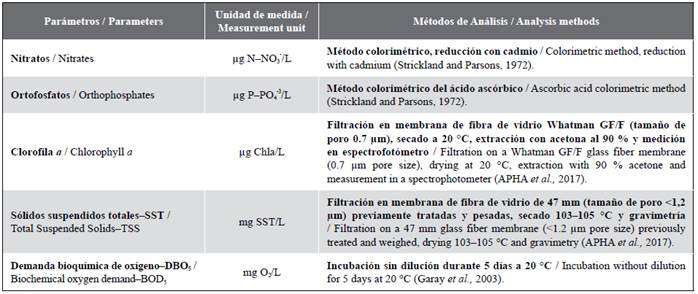

To evaluate the water quality in channels and swamps, we established six sampling stations (A1-A6; Figure 1). We measure in situ temperature, salinity, pH, and dissolved oxygen (DO) of the surface water, three times at each station, using a HACH multiparameter. Additionally, we collected a water sample at a depth of 30 cm, with field control, traveling control sample, and replicas, to measure the parameters described in Table 1. Before HR in the rainy season, we were unable to perform measurements at station A6.

We selected ten stations within the mangrove forest (M1-M10; Figure 1), of which M1-M2 and M7 were located in the preserved mangrove as reference stations. Stations M3-M6, M8-M10 were located in the mangrove forest degraded by the salt crust formation. At each station, the salinity, temperature, and pH in the surface and interstitial waters (depth: 0.5 m) were measured at three points, using the HACH multiparameter, and the water level was determined using a ruler. We use the methodology Invemar (2018a) to obtain the interstitial water samples. At station M7, it was not possible to perform measurements before HR in the rainy season.

We compared our results with the national criteria for flora and fauna preservation in estuarine waters (MinAmbiente, 2015) and with reference values. The Index of Marine and Coastal Waters Quality for Flora and Fauna Preservation (ICAMPFF) was calculated in channels and swamps, with data of DO, pH, nitrates, orthophosphates, TSS, chlorophyll a, and BOD5 (Invemar, 2018b), and with a confidence margin of 86 %. The ICAMPFF qualifies the water quality as optimal, adequate, acceptable, inadequate, and poor (Invemar, 2018b). The significant differences between the four samplings carried out before and after the HR were determined with the Kruskal-Wallis test, in InfoStat® professional version 2016, with a 95 % confidence interval.

In the surface water of channels and swamps, the values of temperature, salinity, and pH decreased after the HR (Figure 3a-c), showing significant differences between the samplings before and after the HR (Temperature: P = 0.006; Salinity: P = 0.004; pH, P = 0.011). The DO increased slightly after HR in some stations (Figure 3d), without significant differences. BOD5, nitrates and nitrites increased and TSS decreased after HR (Figure 3e-h), showing significant differences before and after HR (BOD5: P = 0.006; TSS: P = 0.005; nutrients: P = 0.001). The chlorophyll-a concentration did not show significant differences.

Figure 3 Results of the water physicochemical parameters in channels and swamps: ARH-ES (before HR, dry season), D2RH-ES (after two months of HR, dry season), ARH-EL (before HR, rainy season) and D5RH-EL (after five months of HR, rainy season). **Reference for water classification according to salinity (Knox, 2001). *Permissible limits of Colombian legislation for flora and fauna preservation in estuarine waters (MinAmbiente, 2015).

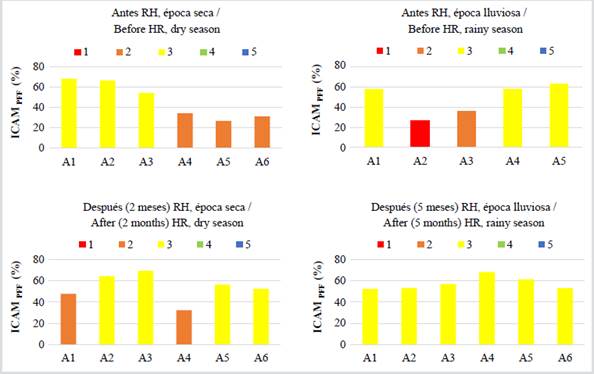

The ICAMPFF showed that before the HR in the rainy season the water quality was poor and inadequate at stations A2 and A6 respectively, and acceptable in the other stations; and in the dry season, the water quality was inadequate at stations A4-A6 and acceptable at stations A1-A3 (Figure 4). After two months of the HR, water quality improved at all the stations, except for A1 and A4; and after five months, the water quality was acceptable at all stations (Figure 4).

Figure 4 ICAMPFF results before and after HR in the Dago-Ustria sector, DMI Cispata. Classification of water quality according to ICAMPFF: 1) poor, 2) inadequate, 3) acceptable, 4) adequate, and 5) optimal.

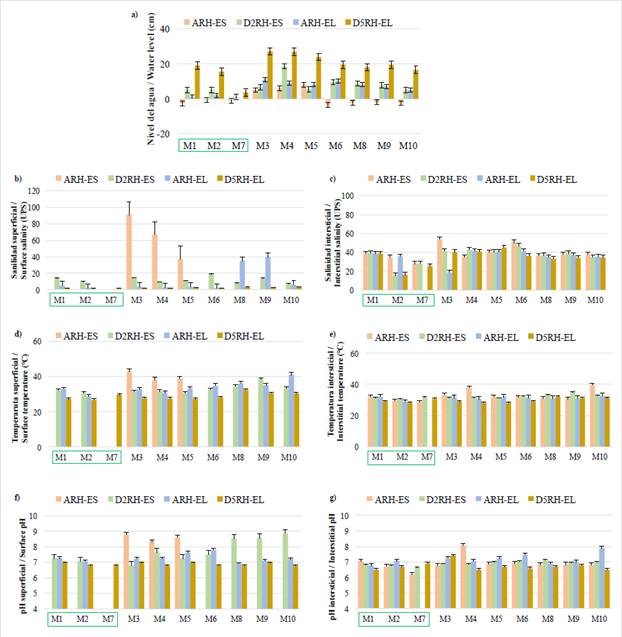

After the HR, flooding within the mangrove forest increased (Figure 5a), showing significant differences before and after the HR (P = 0.0001). The highest salinities, temperature, and pH were recorded at the degraded mangrove stations, which decreased after HR (Figure 5b-d), showing significant differences before and after HR (Salinity: P = 0.0028; temperature: P = 0.0001; pH: P = 0.0005). Between the reference stations and those of the degraded mangrove, salinity, temperature, and pH of the water after the HR were not significantly different.

Figure 5 Results of the physicochemical parameters of the water within the mangrove forest. Sampling: ARH-ES (before HR, dry season), D2RH-ES (after two months of HR, dry season), ARH-EL (before HR, rainy season), and D5RH-EL (after five months of HR, rainy season). The green boxes indicate the reference plots (M1, M2, and M7).

The HR improved the physicochemical conditions of the water in the study area, resulting in acceptable conditions for the preservation of fauna and mangrove plants. The climatic season can accelerate or limit the changes in the water physicochemical parameters (Invemar, 2018a); therefore, long-term water quality monitoring is necessary.

The HR allowed freshwater to enter the channels, swamp, and within the mangrove forest of the Ustria sector in the dry season, reducing salinity to < 10. This salinity is characteristic of oligohaline brackish waters (> 0.6-10; Knox, 2001) and is optimal for seedling growth (3-27; Krauss et al., 2008). Likewise, the temperature of the surface water decreased. At the M3 station, 43 °C were recorded in the surface water before the HR, which exceeds 35 °C and can affect the growth of propagules (Febles et al., 2007), besides causing necrotic lesions on the leaves by overcoming 40 °C (Krauss et al., 2008) and influencing other physicochemical parameters related to nutrition (Reef et al., 2010). After HR, the water temperature ranged between 28-32 °C, adequate for the growth of mangrove seedlings (Krauss et al., 2008).

The pH of the water in channels and swamps was within the permissible range for flora and fauna preservation (Figure 3c). Within the mangrove forest, the pH of the water was similar to that registered at the reference stations and was within the typical range reported for mangroves from the Colombian Caribbean (5.0-8.2; Garcés-Ordóñez and Vivas-Aguas, 2014). This pH favors the availability of essential nutrients (Reef et al., 2010). At most stations, the DO was lower than the permissible limit for flora and fauna preservation in estuarine waters (Figure 3d) and below 2 mg O2/L (suboxic condition), associated with the increased BOD5, possibly due to the removal of organic matter during the HR.

In conclusion, in the short term, the HR in the Dago-Ustria sector induced rapid changes in the physicochemical conditions of the water in the channels, swamps, and within the degraded mangrove forest, improving the water quality for the preservation of fauna and mangrove plants. Long-term water quality monitoring (> five years) is necessary to show significant changes adjusted to temporary environmental variations. In addition, it is equally necessary to include and monitor of biological indicators (fish and natural regeneration) that respond to improvements in the habitat conditions. This long-term monitoring will yield information for the adaptive management of mangrove restoration in the Cispata DMI and in other mangrove areas of Colombia.

text in

text in