INTRODUCTION

Annelids (phylum Annelida) are an important component of benthic communities in the seas around the world (Struck, 2011). These marine organisms may as well be the most abundant and representative invertebrates in reefs (Londoño-Mesa et al., 2016), as they play a key role in the recycling of nutrients, they generate hollows and shelter for other invertebrates, and some families can be indicators of an ecosystem’s health.

The bodies of annelids are generally divided into three basic regions: the acron (where the prostomium and peristomium can be found), the trunk (where the majority of segments are located), and the posterior region (where the pygidium is located) (Harris et al., 2009). There is a great variety of forms within this class, which range from those with an errant lifestyle, such as the families Eucinidae and Nereidae, to those in the Amphinomidae family, commonly called fireworms, coralivorous animals that come in a great variety of sizes (Grimes et al., 2020). Sessile lifeforms live in tubes, adhering to substrate, such as the representatives of the families Sabellidae and Serpulidae, often known as feather duster worms or sea flowers. Their name is due to their shape and the coloration of their gill crown located in the anterior region of the body, which, when extended, resembles a hand fan (Piazzolla et al., 2020).

Their distribution encompasses all the seas in the world, from the intertidal zone down to abyssal depths (Lagos et al., 2018). The study of annelids in Colombia has been enriched with new records for the Colombian Caribbean and locations such as the bays of Santa Marta, Neguanje and Cartagena, Cispatá, and the islands of Providencia and Tortuguilla (Dueñas, 1981, 1999; Rodríguez-Gómez, 1988; Báez and Ardila, 2003; Quirós-Rodríguez et al., 2013; Dueñas-Ramírez and Dueñas-Lagos, 2016; Lagos et al., 2018; León et al., 2019). It is known that the study of annelids began with less than 50 species in the 1960s, a number that progressively grew. Coinciding with the discovery and application of molecular techniques, the records increased, with more than 253 species in 2003. The most recent list, elaborated by León et al. (2019), shows around 293 species distributed in 230 genera and 51 families associated with different regions of Colombia (Magdalena, San Andrés and Providencia, Guajira, the Gulf of Morrosquillo, the Coral Archipelagoes, and Darién), as well as in different types of ecosystems (mangroves, soft and hard seabeds, coastal estuaries and lagoons, algae, and seagrass, among others).

Banco de las Ánimas is a small and hard to access reef formation (Díaz et al., 2000). Studies have been recently conducted which have allowed understanding aspects of the conformation of sandstone bottoms (Zea et al., 2019), as well as an approximation to their biodiversity (García-Urueña et al., 2020). However, studies are still required on groups that have not been so far studied, such as annelids, which belong to reef cryptofauna. This work is a contribution to the knowledge on annelid fauna in the country, and it constitutes a first attempt to characterize this group in little explored areas such as Banco de las Ánimas. Twenty-three species previously unregistered for the Colombian Caribbean were found. It is recommended that future work consider an approach that includes additional morphological techniques such as confocal laser scanning microscopy and electronic microscopy, with the purpose of obtaining additional information on ecological, geographical, and phylogenetic relations aspects that can enrich the obtained information (Di Domenico et al., 2014; Lagos et al., 2018).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

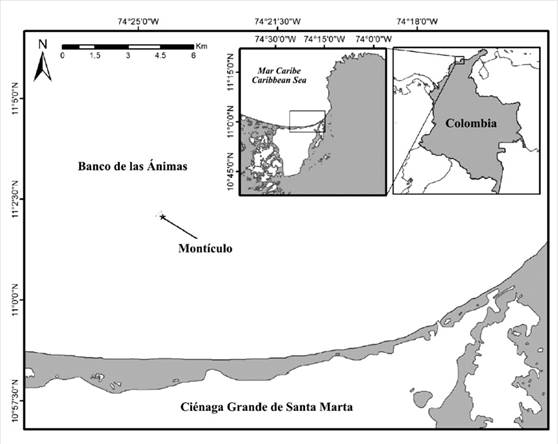

Banco de las Ánimas (11° 02’04 0”N-74° 24’ 22,8”W) is located at approximately 12 km north from the coast of Salamanca Island, in front of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (CGSM; Figure 1) (Díaz et al., 2000) in the Colombian Caribbean, in an area that is strongly influenced by the discharges of the CGSM. The oceanic conditions are similar to those found in the Tayrona National Natural Park (PNNT) (Bula-Meyer and Díaz-Pulido, 1995; Arévalo-Martínez and Franco-Herrera, 2008), with two marked climate seasons and an intermediate one. The dry season comprises December to April; the rainy one, August to November; and there is a transition phase between May and June. The area is also influenced by the behavior of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and regional high-pressure systems (Franco, 2005).

Field phase

In the Montículo sector and at a depth of 14 m, four autonomous reef monitoring structures (ARMS, Figure 2) were set up, according to a methodology proposed by the NOAA (Moews-Asher et al., 2018). These consist of a 35 x 45 cm baseplate supporting nine removable 22.5 x 22.5 cm PVC plates. The ARMS were removed after 6, 8, 12, and 18 months (May, August, and November 2017, as well as June 2018).

Laboratory phase

The disassembly of the structures was performed in compliance with Leray and Knowlton’s protocol (2015) by carefully separating the specimens from the plates, which were sedated in magnesium chloride at 7%, photographed, and finally fixed in formalin at 10%. Their diagnostic taxonomic characteristics were identified and documented in order to determine the identity of the specimens, down to the lowest possible taxonomic level. Taxonomic guides and books were utilized as morphological reference (Fauchald and Reimer, 1975; Fauchald, 1977; Uebelacker and Johnson, 1984; Solis-Weiss, 1995; Beesley et al., 2000; De León-González, 2009; Ferreira-Gil, 2011), as well as searches in specialized database such as the World Polychaeta Data Base (http://www.marinespecies.org/polychaeta/), in order to review the original descriptions.

As important results, we present a brief diagnosis of the species, additional information on the examined material, and the synonyms of each species, which were consulted in the WoRMS website (http://www.marinespecies.org/index.php). Furthermore, we include the photographic material, where some of the structures of the specimens under study are highlighted. The pictures were taken with a Leica LMT260 XY Scanning Stage stereoscope and processed with the Multistep software of the Leica Application Suite. The organisms belonging to the phylum Annelida were deposited in the Germán Bula Meyer Collections Center of Universidad del Magdalena, registered in the Non-insect Invertebrates collection (Macrofauna) under catalog numbers CBUMAG:MAC:02036 to CBUMAG:MAC:02129.

RESULTS

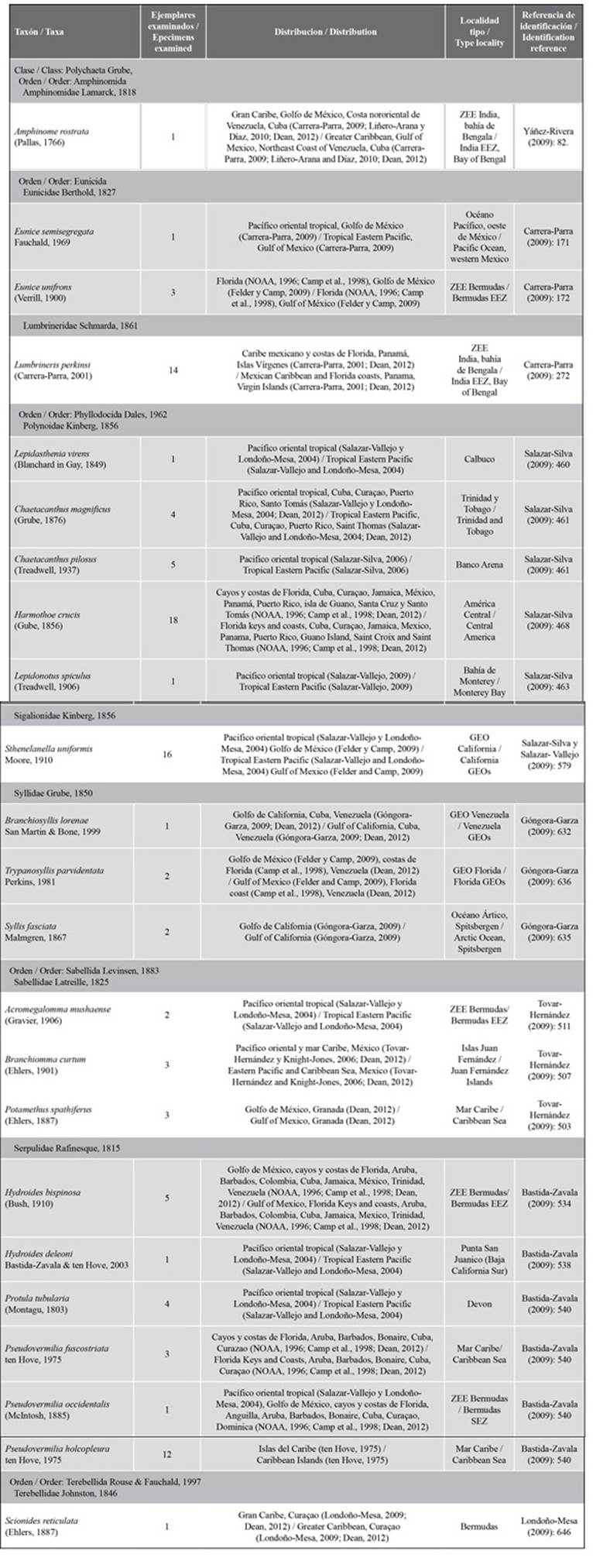

One hundred four (104) individuals were collected and identified, which were grouped into 9 families. Twenty-three species are new records of annelids for the Colombian Caribbean (Table 1). The polynoid Harmthoe crucis was the most abundant, with 18 specimens. Next, Table 1 presents the taxonomy. The studied specimens’ geographical distribution, type locality, and identification reference are provided.

Table 1 New records of annelids for the Colombian Caribbean associated with the ARMS structures (Autonomous Reef Monitoring Structures) of the Banco de las Ánimas. Some type localities are expressed as EEZs (Exclusive economic Zones, which comprise a marine area to certain nations have special rights to research and use marine resources) and GEOs (established marine regions).

Family Amphinomidae Lamarck, 1818

Amphinome rostrata (Pallas, 1766)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=129825).

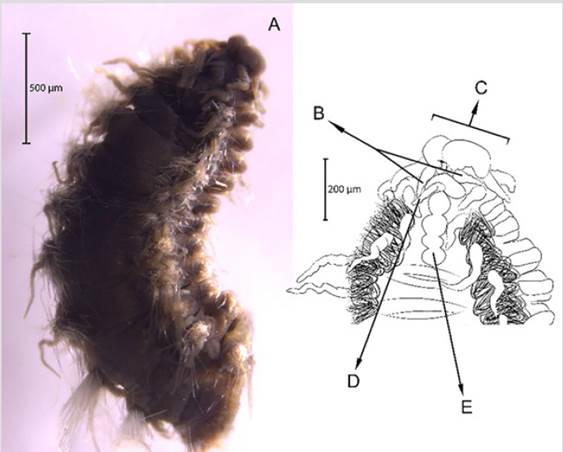

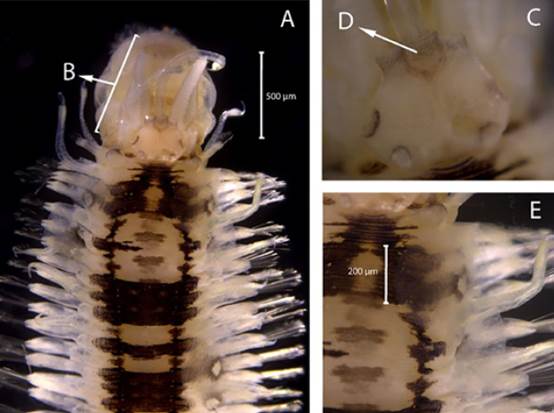

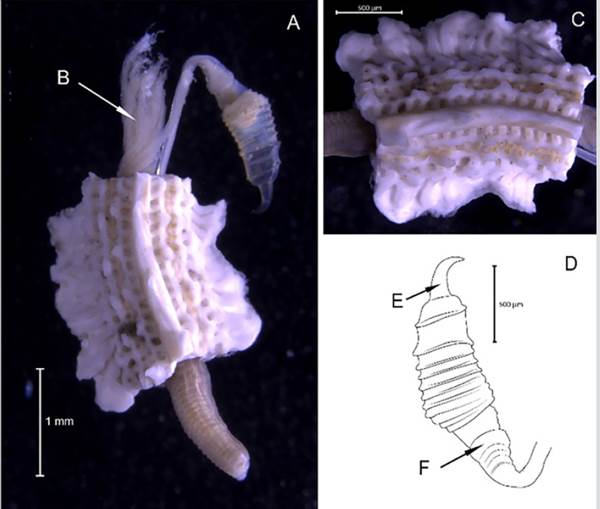

Examined material. 2.2 mm long and 0.5 mm wide individual (Figure 3 A). Specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02050.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with median antenna and two laterals (Figures 3B, 3C, 3D), with a sinuous caruncle that surpasses the third setiger (Figure 3E). Elongated and robust body, biramous parapodia, and simple setae. Gills on the notopodium.

Family Eunicidae Berthold, 1827

Eunice semisegregata Fauchald, 1969

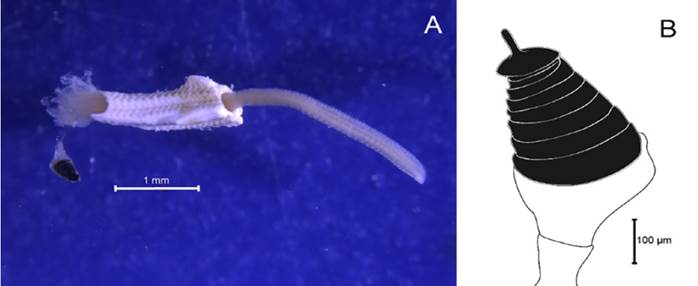

Examined material. Incomplete individual, 12.2 mm long and 0.5 mm wide (Figure 4A). Specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02062.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with five antennae and two articulate peristomial cirri (Figures 4B, 4C, 4D, 4F). No divided palps. Elongated, incomplete body with black, bidentate sub-acicular hooks. Additional setae are simple, spinigerous, and pectinate; complex ones are falcigerous.

Eunice unifrons (Verrill, 1900)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333349)

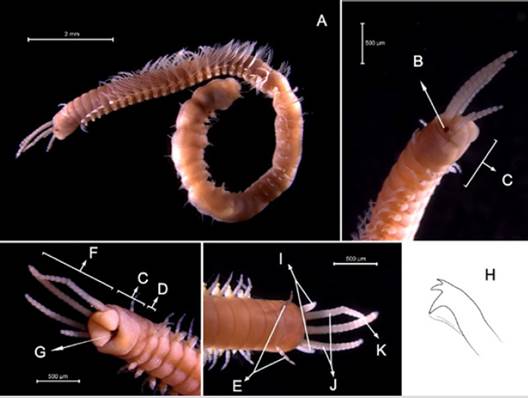

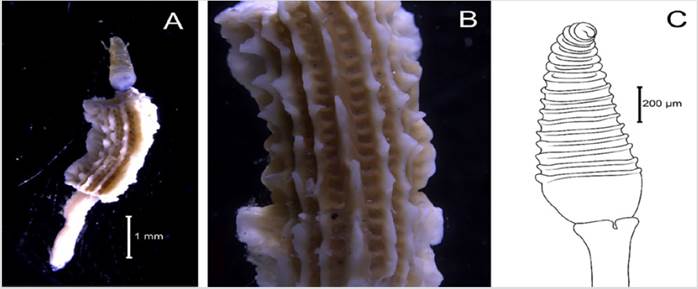

Examined material. 16.6 mm long and 0.6 mm wide individual (Figure 5A). Three specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02048.

Diagnosis. The prostomium has five articulated prostomial appendices (Figure 5B, 5F, 5J). The median antenna reaches parapodium No. 2 (Figure 5K). Two short and articulated peristomial cirri (Figure 5C, 5D, 5E, 5I) that do not reach the anterior margin of the peristomium. Tridentate yellow sub-acicular hooks (Figure 5H), with simple spinigerous, pectinate setae and compound falcigers. Needles without mucron. The gills are longer than the dorsal cirrus, and the individual has a jaw (Figure 5G).

Family Lumbrineridae Schmarda, 1861

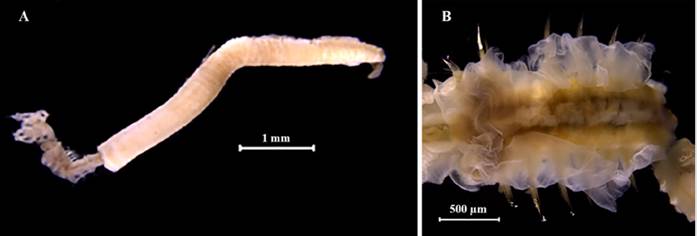

Lumbrineris perkinsi (Carrera-Parra, 2001)

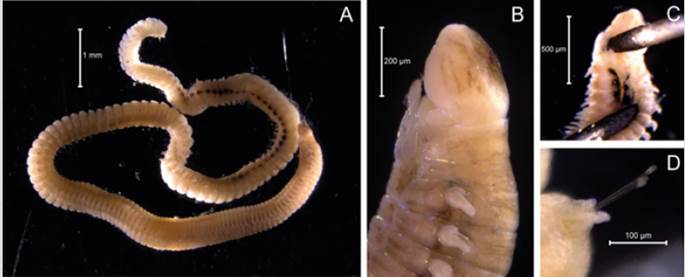

Examined material. 18.1 mm long and 4.6 mm wide individual (Figure 6A). 15 specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02070.

Diagnosis. Slightly conical, rounded prostomium with a pair of obscure longitudinal dorsal bands. Elongated body, whole peristomium, no appendices or antennae (Figure 6B). The setae are simple hooded multidentate hooks (Figura 6D), and, ventrally, in the medium-posterior region, the individuals have a central line with dark spots. The anterior parapodia do not have gills and have a maxillary apparatus (Figure 6C).

Lepidasthenia virens(Blanchard in Gay, 1849)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333804).

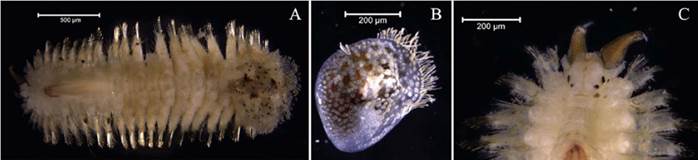

Examined material. 3.6 mm long and 0.7 mm wide individual (Figure 7A). One specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02057.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with median dorsal antenna and non-fused tentacular segment (Figures 7B, 7C, 7D). Long body. The organism has scales on its dorsum (Figure 7A). Pairs of elytra in segments 2, 4, 5, and 7; segments alternate to 23, and afterwards every three segments. Small elytra, not covering the dorsum, and a pattern of dark transversal bands (Figure 7E). Setae at the base of the lateral cirri and the notopodia.

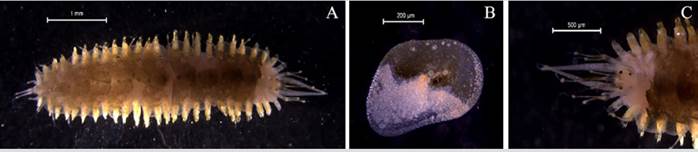

Chaetacanthus magnificus (Grube, 1876)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333251).

Examined material. 2.1 mm long and 0.4 mm wide individual (Figure 8A). Two specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02054.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with frontal median antenna; fused tentacular segment (Figure 8C). Lateral antennae with ceratophores Short, robust body with dorsum covered by scales (Figure 8A). Elytra with globular macrotubercles (Figure 8B). The anterior ones have non-pedunculated macrotubercles forming a line, and posterior ones have flat macrotubercles, which are irregular and form a patch that looks like a vitreous crust. Spinous non-lanceolate notosetae. Gill filaments are located dorsolateral to the parapodia.

Chaetacanthus pilosus (Treadwell, 1937)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333252).

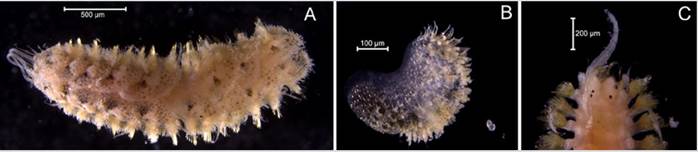

Examined material. 2.0 mm long and 0.3 mm wide individual (Figure 9A). Five specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02055.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with frontal median antenna; fused tentacular segment (Figure 9C). Ceratophores in the terminal lateral antennae. Spinous non-lanceolate notosetae. Elytra with ovoid microtubercles and pedunculated macrotubercles spread across the surface (Figure 9B). Gill filaments are located dorsolateral to the parapodia.

Harmothoe crucis (Gube, 1856)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333563).

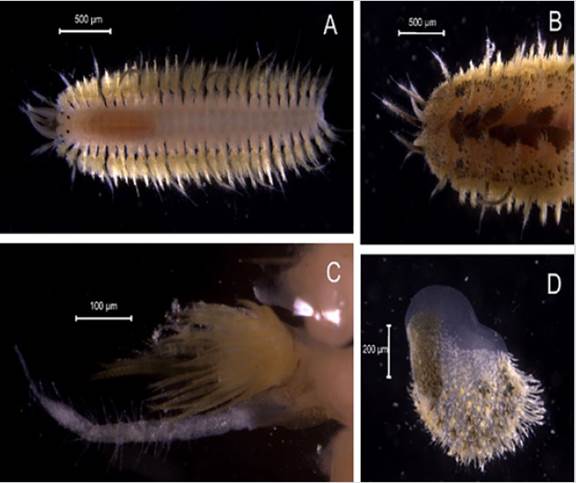

Examined material. 2.5 mm long and 0.2 mm wide individual (Figure 10A). 18 specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02061.

Diagnosis. Prostomium with one facial tubercle and a median antenna inserted in the frontal cetaphore (Figure 10B). Individual with a robust body and dorsum covered with elytra (Figure 10A). The majority of neurosetae have a bidentate tip (Figure 10C). The surface of the anterior elytra without a sclerotized covering; abundant notosetae and up to 15 pairs of elytra. Posterior segments from 6 to 8 have non-alternated dorsal cirri with elytra. The surface of the elytra has abundant microtubercles with abundant marginal buds (Figure 10D). The macrotubercles of the median and posterior elytra are cylindrical, with the tip expanded into four bifurcated projections.

Lepidonotus spiculus (Treadwell, 1906)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333826).

Examined material. 3.7 mm long and 0.7 mm wide individual (Figure 11A). Two specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02085.

Diagnosis: Prostomium with median antenna and laterals with globose subdistal bulges, all three on terminal cetaphores. Tentacular segment fused with the prostomium (Figure 11C). Body with 26 segments and 12 pairs of elytra (Figure 11B). Palps with tiny buds. Spinigerous, flat lanceolate notosetae. Simple lanceolate neurosetae. Pygidium with two anal cirri similar in shape to the antennae and the rest of the cirri.

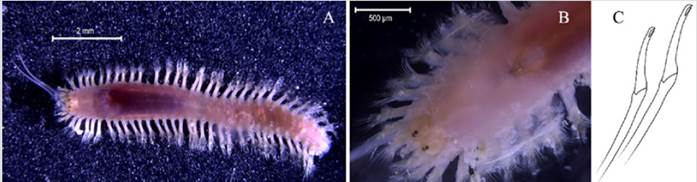

Sthenelanella uniformis (Moore, 1910)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=332194).

Examined material. 5.7 mm long and 0.5 mm wide individual (Figure 12A). 14 specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02081.

Diagnosis: The prostomium is round, it is as long as it is wide, and the ocular area is not elevated. The robust body (Figure 12A) has long palps with cetaphores. Median and lateral antennae with cirrophores; it has four eyes (Figure 12B). Lateral antennae fused with tentacular parapodia; the median antenna’s cetaphore has atria. The parapodia have ctenidia. Spinous notosetae and neurosetae are long-bladed falcigers. (Figure 12C).

Syllidae Family Grube, 1850

Branchiosyllis lorenae San Martin & Bone, 1999

Examined material. 14.12 mm long and 0.41 mm wide individual (Figure 13A). One specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02081.

Description. The body is sub-cylindrical, ventrally flat (Figura 13A), and with fused palps at the base. It has nuchal organs and antennae and tentacular and dorsal cirri (Figure 13B). The pharynx is armed with a trepan and bidentate falcigers. Articulated anal cirri.

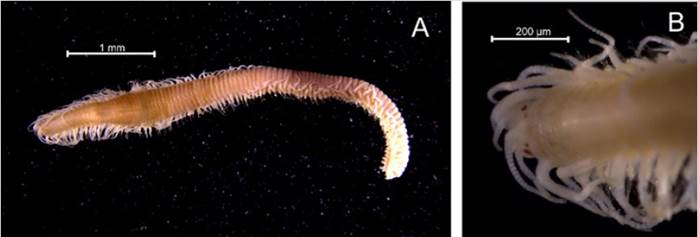

Trypanosyllis parvidentata (Perkins, 1981)

Examined material. 4.96 mm long and 0.31 mm wide individual (Figure 14A). Two specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02059.

Diagnosis. The prostomium has nuchal organs, antennae, articulated tentacular cirri, and fused palps at the base. The body is sub-cylindrical (Figure 14A) and ventrally flat (Figure 14B). Articulated dorsal cirri. The pharynx is armed with a trepan, which has 10 tiny teeth and a big median-dorsal tooth. Articulated anal cirri.

Syllis fasciata Malmgren, 1867

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=131429).

Examined material. 12.6 mm long and 0.2 mm wide individual (Figure 15A). Two specimens deposited under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02059.

Description. Sub-cylindrical body with a flat ventral zone (Figure 15A). The antennae and the tentacular and dorsal cirri are articulated; the individual also has nuchal organs. Fused palps at the base and mainly compound setae. The internodes of some compound setae have the shape of a claw, generally bent against the shank. All cirri have approximately the same shape (Figure 15B), and the pharynx is armed with a median-dorsal tooth in the anterior region. No gills or falcigers in the anterior setigers. Articulated anal cirri.

Family Sabellidae Latreille, 1825

Acromegalomma mushaense (Gravier, 1906)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=994115).

Examined material. 5.53 mm long and 0.88 mm wide individual (Figure 16A). Two specimens deposited under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02036.

Description. Radioles with transversal dark bands; compound subdistal eyes (Figure 16B). Gill lobes are dorsally fused. With numerous abdominal segments, abdominal tori form shallow transversal crests. Avicular thoracic uncini with three teeth in the apical region, as well as a short manubrium. No paleate neurosetae; elongated inferior thoracic neurosetae with a wide covering and/or fusiform, long tips. Dorsal margins of the collar are not fused with the fecal grove, with no dorsal sacs.

Branchiomma curtum (Ehlers, 1901)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=333130).

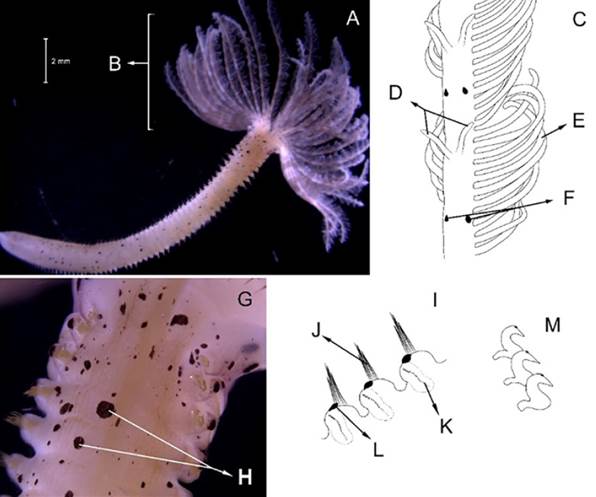

Examined material. 51.46 mm long and 1.12 mm wide individual (Figure 17A). Three specimens deposited under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02038.

Diagnosis. Radioles with paired stylodes alternating with compound, paired eyes (Figure 17B) distributed along the individual (Figures 17C, 17D, 17E, 17F). Maculae along the body of the individual (Figure 17H). Each parapodium has a black spot at the base of the limbate notopodial setae (Figures 17I, 17J, 17K, 17L). The thorax (Figura 17G) has avicular thoracic uncini with a short manubrium, as well as two spines in the apical region (Figure 17M). With numerous abdominal segments, the tori of uncini conical lobes, with no accompanying setae (Figure 17K).

Potamethus spathiferus (Ehlers, 1901)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=130953).

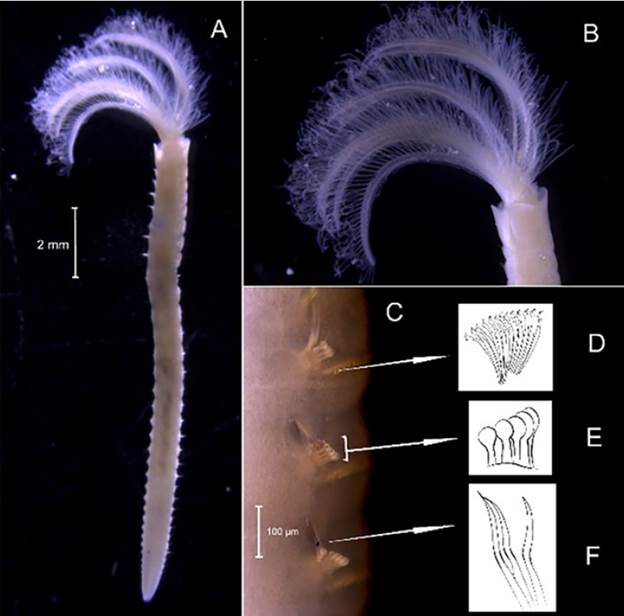

Examined material. 5.53 mm long and 0.89 mm wide individual (Figure 18A). Three specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02075.

Diagnosis. Branchiotentacular crown without stylodes or compound eyes; the radii are not dorsally fused. Abdomen with numerous segments. Thoracic avicular uncini have a very long manubrium and simple paleate and simple limbate thoracic notopodial setae (Figures 18C, 18D, 18E, 18F); the ventral lobes of the collar are elongated (Figure 18B).

Family Serpulidae Rafinesque, 1815

Hydroides bispinosa Bush, 1910

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=421083).

Examined material. 4.12 mm long and 0.28 mm wide individual (Figure 19A, 19C). Five specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02052.

Description. Branchiotentacular crown (Figure 19B), complex operculum with basal funnel and a distal whorl (Figures 19A, 19D, 19F, 19G, 19H, 19I, 1J). Whorl spines are curved inwards and the opercular pedicle is soft and non-calcified, with no wings or digital processes. The opercular funnel radii have a rounded tip. Abdominal setae with the shape of a flattened trumpet. Whorl spines with a pair of lateral spinules. Strongly ornamented tube with no internal longitudinal ribs (Figure 19E).

Hydroides deleoni (Bastida-Zavala & ten Hove, 2003)

Examined material. 5.10 mm long and 0.23 mm wide (Figura 20A). One specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02058.

Diagnosis. Branchiotentacular crown with a modified radiole in the operculum with basal funnel and distal whorl (Figure 20A). The opercular pedicle is soft and non-calcified, with no wings or digital processes. Opercular funnel with sharp end at each radius (Figure 20E). Abdominal setae with the shape of a flattened trumpet. Whorl spines are lateral spinules (Figures 20B, 20C, 20D). In addition, the whorl has a free dorsal hook, with one or more dorsal spines larger than the others and with varying tips, in addition to being curved inwards, with no pronounced protuberances. Strongly ornamented tube, with no internal longitudinal ribs.

Protula tubularia (Montagu, 1803)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=131035).

Examined material. 4.76 mm long and 0.43 mm wide (Figure 21A). Three specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02076.

Diagnosis. This genus and Subprotula are the only representatives of the family with no operculum. Radioles with no processes at the end of the interradiolar membrane; crown with 12 to 15 radioles per lobe. The setae of the collar are limbate, and the uncini have a very long main tooth. The thoracic membrane is well developed (Figure 21B). Abdominal setae consisting of acicular notopodial uncini and limbate spinigers in the neuropodium. Flat calcified tube, little ornamented, simple, and white-colored, with no longitudinal ribs (Figure 21A).

Pseudovermilia fuscostriata (ten Hove, 1975)

Examined material. 2.92 mm long and 0.39 mm wide individual (Figure 22A). Three specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02077.

Diagnosis. Anterior region with branchiotentacular crown, which has a modified radiole in its cylindrical uncalcified pedicle (Figure 22B). The operculum is not black; it is hardened, topped with a simple curved spine (Figure 22D, 22E), with deep annulate groves. The base is thickened (Figure 22F). Abdominal geniculate setae and thorax with apomatus-type setae. The collar has setae, and the thoracic membrane ends in the second setiger. Thoracic uncini with a bifurcated anterior tooth. The tube showed brown-colored transversal bands (Figure 22C).

Pseudovermilia occidentalis (McIntosh, 1885)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=131036).

Examined material. 4.17 mm long and 0.22 mm wide individual (Figure 23A). One specimen logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02079.

Diagnosis. Cylindrical, uncalcified opercular pedicle. The operculum is black, with a simple spine (Figure 23B), which, in some cases may or may not have several lesser spines. Abdominal geniculate setae and thorax with apomatus-type setae. The collar has setae, and the thoracic membrane ends in the second setiger; the thoracic uncini have a bifurcated anterior tooth. White tube with a longitudinal crest and transversal groves, sometimes with peristomes (Figure 23A).

Pseudovermilia holcopleura (ten Hove, 1975)

Examined material. 4.30 mm long and 0.46 mm wide individual (Figure 24A). 15 specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02078.

Diagnosis. Cylindrical, uncalcified opercular pedicle. The operculum is transparent or white, with subtle annulate groves, in some cases with a distal spine (Figure 24C). Abdominal geniculate setae and thorax with apomatus-type setae. The collar has setae, and the thoracic membrane ends in the second setiger. The thoracic uncini have a bifurcated anterior tooth. Calcified tube with a white, brown combination, strongly ornamented, with no annulations in some cases (Figure 24B).

Terebellidae Family Johnston, 1846

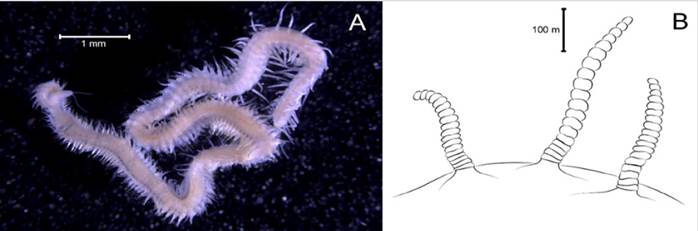

Scionides reticulata (Ehlers, 1887)

Synonyms in:Read and Fauchald (2021) (accessed through https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=334736).

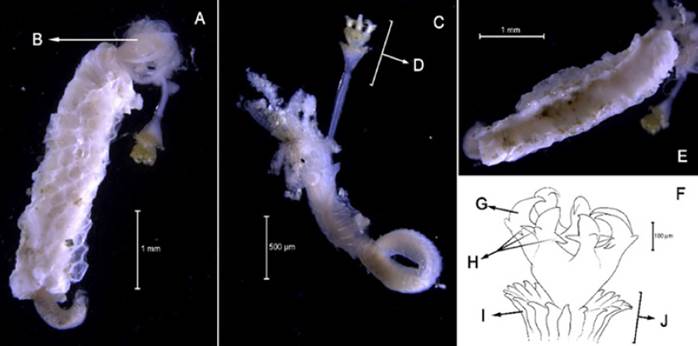

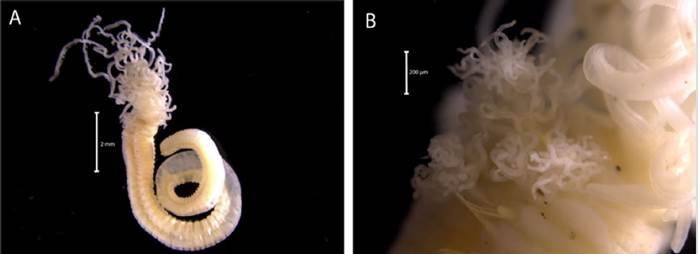

Examined material. 14.9 mm long and 0.9 mm wide individual (Figure 25A). Two specimens logged under catalog number CBUMAG:MAC:02056.

Diagnosis. Elongated body with 31 thoracic segments. It is dorsally convex and lateroventrally flat, narrowing at the abdomen (Figura 25A). Oral tentacles, very numerous and long. Thoraci uncini in double rows in some setigers, like a zipper. No eversible, papillate pharynx, and the notosetae have serrated, limbate tips. Three pairs of filamentous gills with much reduced stalks, in some cases with no stalk (Figure 25B).

DISCUSSION

Twenty-three new records for the Colombian Caribbean Sea were added to the species listed by Dueñas (1999), Báez and Ardila (2003), Dean (2012), and León et al. (2019). Some of them had been recorded in the Pacific coast of Mexico and the United States, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico (Uebelacker and Johnson, 1984). The genera recorded in this study have a variable distribution throughout many sectors of the Caribbean and the Pacific, and so far, none of the recorded species is considered to be invasive.

Most of the species belong to the family Serpulidae, which has been recognized as one of the most conspicuous in the reef environments of the Colombian Caribbean (Bastida-Zavala, 2009). Serpulids stand out due to their diversity of operculum shapes and the variety of ornaments in their calcified tubes, such as longitudinal or transversal ribs with a higher or lower degree of development found in the genera Hydroides and Pseudovermilia (Uebelacker and Johnson, 1984). They are mainly associated with hard substrates, and they can also settle on a solid substrate that is available, such as the one constituted by the ARMS. This type of artificial reef is considered to foster the recruitment and reproduction of marine organisms (Seaman and Jensen, 2000), and the communities settling on it may be very different to those in their environment (commonly reef or rocky).

The presence of some species previously recorded in the Pacific Ocean is highlighted (E. semisegregata, C. pilosus, L. virens, S. uniformis, and A. mushaense), as well as that of some species of the genera Hydroides and Pseudovermilia. This pattern agrees with other research on annelids belonging to the meiofauna, as is the case of Lagos et al. (2018), who stated that many of the species found as new records have a very wide distribution area and have been previously reported in different areas of the Caribbean. They may even have records in different oceans (Rocha, 2003; Floeter et al., 2008; Luiz et al., 2012). These geographical distribution patterns have been also found in other cryptic organisms such as ascidians (Nóbrega et al., 2004) and reef fish (Floeter et al., 2008; Luiz et al., 2012), and they can be explained by the dispersion stages allowing for the flow of genes between distant populations. Despite this, it is important to delve into this aspect in future research, considering that Di Domenico (2014) states that some macrofauna annelid species may have pelagic larvae that manage to spread. However, this is unlikely for other species such as interstitial ones be able to spread so widely, given that they are direct developers (Schmidt and Westheide, 1999).

The methodology involving ARMS structures proposed by the NOAA promotes a good settling substrate for mobile and sessile benthic organisms (Leray and Knowlton, 2015), mainly for annelids that are normally considered to be pioneers in colonization processes and may be substantial contributors among the organisms adhering to the plates (Pearman et al., 2016; Ransome et al., 2017). Annelids possess pelagic larvae that can remain in the water column for 24 hours, in some cases for up to 15, until they find an adequate substrate to settle (García-Alonso et al., 2014). Thus, it is possible that the larvae are displaced towards other sites, which allows broadening their geographical distribution. Considering the above, it is necessary to conduct more studies on artificial substrates as reef fauna collectors and compare them to what can be found in a natural environment, thus enriching the information on annelid biodiversity in the Colombian Caribbean. Aspects of integrative taxonomy should also be included with the purpose of obtaining more robust results. This demonstrates the enormous diversity of life existing not only within Banco de las Ánimas, but also throughout the shelf of the gulf of Salamanca, especially considering the high sedimentary load and the variable salinity resulting from the contribution of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta.

CONCLUSIONS

ARMS artificial structures constituted a fixing opportunity for larvae of many species. As for the phylum Annelida, they allowed finding 23 new records. This is a potential sample that invites us to keep researching the Montículo sector of Banco de las Ánimas and its marine biodiversity, as well as to continue with regular sampling programs that allow increasing the knowledge about this group and that of others belonging to the cryptofauna.

text in

text in